Abstract

Background

Inappropriate attendances may account for up to 40% of presentations at accident and emergency (A&E) departments. There is considerable interest from health practitioners and policymakers in interventions to reduce this burden.

Aim

To review the evidence on primary care service interventions to reduce inappropriate A&E attendances.

Design and setting

Systematic review of UK and international primary care interventions.

Method

Studies published in English between 1 January 1986 and 23 August 2011 were identified from PubMed, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database, the Cochrane Collaboration, and Health Technology Assessment databases. The outcome measures were A&E attendances, patient satisfaction, clinical outcome, and intervention cost. Two authors reviewed titles and abstracts of retrieved results, with adjudication of disagreements conducted by the third. Studies were quality assessed using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network checklist system where applicable.

Results

In total, 9916 manuscripts were identified, of which 34 were reviewed. Telephone triage was the single best-evaluated intervention. This resulted in negligible impact on A&E attendance, but exhibited acceptable patient satisfaction and clinical safety; cost effectiveness was uncertain. The limited available evidence suggests that emergency nurse practitioners in community settings and community health centres may reduce A&E attendance. For all other interventions considered in this review (walk-in centres, minor injuries units, and out-of-hours general practice), the effects on A&E attendance, patient outcomes, and cost were inconclusive.

Conclusion

Studies showed a negligible effect on A&E attendance for all interventions; data on patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness are limited. There is an urgent need to examine all aspects of primary care service interventions that aim to reduce inappropriate A&E attendance.

Keywords: emergency medicine, general practice, primary health care, urgent care

INTRODUCTION

A marked rise in accident and emergency (A&E) attendances in the UK in recent years has been accompanied by sharp increases in short-stay admissions and associated costs.1 It has been estimated that between 15% and 40% of A&E attendances are ‘inappropriate’ or ‘avoidable’,2,3 but figures are based on differing definitions of the two terms making comparability difficult.4 Nevertheless, findings from a large number of studies agree that access, patient self-assessment of illness severity, and confidence in the quality of A&E care are key drivers for inappropriate presentation.2,5–7

Reducing inappropriate attendance has long been recognised as an important area for intervention by policymakers,8 who have focused on expanding access to primary care and improving triage systems so patients are redirected to the most appropriate care. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the available evidence on whether expanding access to primary care services reduced inappropriate A&E attendances; that is, all A&E contacts rather than admissions via A&E. The aims were to evaluate the strength of evidence from the UK and internationally, and to identify areas for future research. For this review, ‘inappropriate’ attendances have been defined as those involving patients with low-acuity presentations who could be directed to other, more appropriate, care services or self-care, rather than A&E.

METHOD

Defining ‘primary care interventions’

Primary care interventions were defined as out-of-hospital care or integrated care interventions to which patients have direct access (that is, without prior gatekeeping), including:

in or out-of-hours primary care — general practice care and GP cooperatives;

community health centres — serving medically uninsured or rural populations with limited primary care access in the US;

minor injuries units, walk-in centres, and urgent care centres — nurse-led services handling low acuity presentations in the UK (‘minor injuries units’ and ‘walk-in centres’ were often used interchangeably in the literature);

telephone triage systems.

Services provided in emergency departments, such as clinical decision units, and GP stations within A&E departments, were excluded. Clinical decision units operate with staff from various hospital-based specialties with little or no experience of general practice,9 and patients in both clinical decision units and GP stations will already have undergone triage or received care in A&E before being seen by primary care practitioners.10

How this fits in

Inappropriate attendances may account for up to 40% of all presentations at accident and emergency (A&E) departments. Policy has focused on redirecting patients to more appropriate forms of care, but there is a lack of high-quality evidence on primary care interventions supporting this aim. This review found no evidence of a reduction in inappropriate A&E attendance following the introduction of a variety of interventions designed to improve access to primary care; the sole exception was US communities that have poor coverage of primary care services. Limited international evidence on available urgent care providers in community settings (for example, emergency nurse practitioners in residential care homes) suggests there may be some benefit from using these interventions to reduce referral rates to A&E departments, but further, robust evaluation of the ‘real-world’ efficacy of such interventions is needed.

Search strategy

Studies published between 1 January 1986 and 23 August 2011 were identified using a systematic search of English-language literature on PubMed, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database, the Health Technology Assessment Database, and Cochrane Collaboration databases. Box 1 gives details of keywords used.

Box 1. Search strategy

Combinations of terms used in initial searches

Accident and emergency OR emergency department OR A&E OR ED OR ER

Primary care OR general practice OR GP (these to be nested within terms such as GP co-operative)

Attendance OR visit

Inappropriate OR unnecessary OR avoidable OR non-essential

Determinants OR factors OR underlying factors OR explanatory factors

Combination searches (to include all interchangeable terms from above)

[terms from 1] AND [terms from 2]

[terms from 1] AND [terms from 3] AND [terms from 5]

[terms from 1] AND [terms from 4]

[terms from 1] AND [terms from 3] AND [terms from 4]

Additional searches

walk-in centre

minor injuries unit

urgent care hub

(hospital based) polyclinic

walk in clinic AND emergency

NHS direct AND [terms from 1]

[terms from 1] AND [terms from 2] AND out of hours

emergency care AND telephone triage

telephone triage AND [terms from 1]

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if:

they were not published in English;

full text was unavailable;

they were editorials or commentaries;

search terms were not present in the body of the paper;

they did not consider a primary care service intervention; or

they did not address at least one of the outcome measures of interest, namely, A&E attendance, clinical outcome, patient satisfaction, and intervention cost.

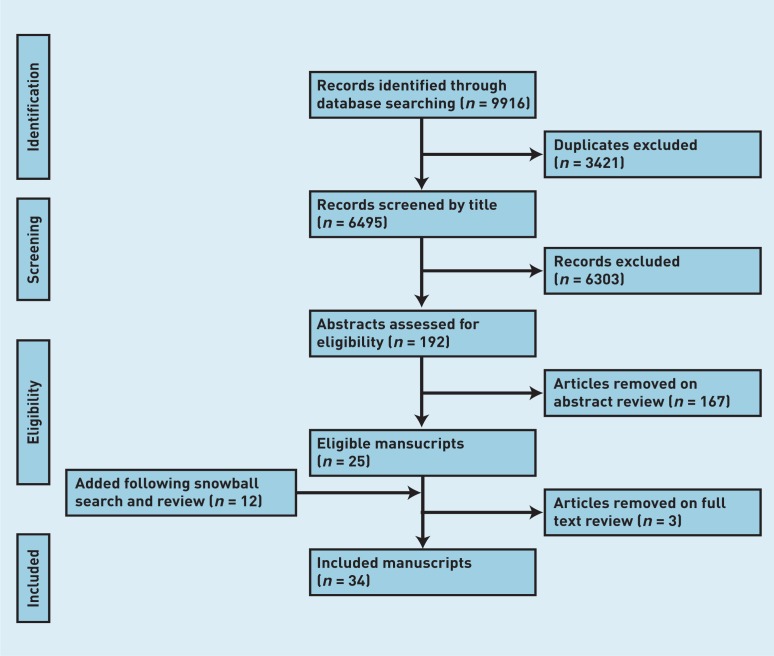

In total, 9916 eligible titles were identified via electronic database searches. Following removal of duplicates, two researchers independently screened the remaining 6495 titles, identifying 192 studies that met the selection criteria (with adjudication by the other researcher on disagreements). Of the 192 abstracts independently reviewed by two researchers (with adjudication by the other researcher on disagreements), 25 studies were eligible for full review. An additional 12 studies were identified for review from the reference lists for these 25 studies. Three studies were removed following detailed evaluation, using the same screening process as above, giving a final total of 34 eligible studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the review process.

Assessment of quality

In accordance with Royal College of Physicians (RCP) guidance on critical appraisal,11 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) checklists were adopted to assess study quality after classifying study methodologies using the SIGN algorithm. Eight studies were eligible for quality assessment; the remaining 26 studies were not. SIGN quality ratings are assigned to studies in Table 1 in accordance with the definitions outlined in Appendix 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies by primary care intervention (n = 34)

| Study | Year | Country | Study type | SIGN quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone triage (n= 11) | ||||

| Bunn et al2 | 2004 | Various | Meta-analysis/systematic review | 2++ |

| Dunt et al13 | 2005 | Australia | Before–after/interrupted time series | 3 |

| Graber et al14 | 2003 | New Zealand | Cross-sectional study | 3 |

| Lattimer et al15 | 2005 | UK | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| Munro et al16 | 2001 | UK | Non-comparative (case series/study) | 3 |

| Munro et al17 | 2005 | UK | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| Shekelle and Roland 18 | 1999 | Various | Non-comparative (case series/study) | 3 |

| Stacey et al19 | 2003 | Various | Meta-analysis/systematic review | 2++ |

| Stewart et al20 | 2006 | UK | Cohort study | 2+ |

| South Wiltshire Out of Hours Project21 | 1997 | UK | Non-comparative (case series/study) | 3 |

| Vedsted and Olesen22 | 1999 | Denmark | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| Walk in clinics (n= 2) | ||||

| Chalder et al24 | 2003 | UK | Cross-sectional study | 3 |

| Salisbury et al25 | 2007 | UK | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

|

| ||||

| Community health centres (n= 2) | ||||

| Choudhry et al29 | 2006 | US | Non-comparative (case series/study) | 3 |

| Rust et al30 | 2009 | US | Cross sectional study | 3 |

|

| ||||

| GP out of hours/GP cooperatives (n= 11) | ||||

| Bury et al31 | 2006 | Ireland | Cross-sectional study | 3 |

| Moll van Charante et al32 | 2007 | The Netherlands | Cross-sectional study | 3 |

| O’Keeffe et al33 | 2008 | Ireland | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| O’Kelly et al34 | 2001 | Ireland | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| Pickin et al36 | 2004 | UK | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| Philips et al35 | 2010 | Belgium | Non-randomised controlled trial | 1– |

| Salisbury et al25 | 1997 | UK | Cross-sectional study | 3 |

| Van Uden and Crebolder38 | 2004 | The Netherlands | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| van Uden et al39 | 2005 | The Netherlands | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| van Uden et al37 | 2006 | The Netherlands | Cross-sectional study | 3 |

| Vedsted and Christensen40 | 2001 | Denmark | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| Emergency nurse practitioner (n= 1) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Codde et al41 | 2010 | Australia | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| Various (n= 7) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Arendts et al42 | 2010 | Australia | Non-comparative (case series/study) | 3 |

| Bickerton et al28 | 2011 | UK | Before–after /interrupted time series | 3 |

| Coleman et al27 | 2001 | UK | Non-comparative (case series/study) | 3 |

| Cooke et al4 | 2004 | Various | Meta-analysis/systematic review | 2++ |

| Health Services Utilization and Research Committee2 | 1997 | Canada | Meta-analysis/systematic review | 2++ |

| Liebowitz et al23 | 2003 | Various | Meta-analysis/systematic review | 2++ |

| Murphy7 | 1998 | Various | Meta-analysis/systematic review | 2++ |

RESULTS

The 34 eligible papers comprised six systematic reviews, 13 before–after or interrupted time-series studies, seven cross-sectional studies, six non-comparative case studies, one cohort study, and one non-randomised controlled trial (Table 1). The majority were from Europe and Australia, with 11 (35%) considering interventions introduced in the UK.

Telephone triage (n = 11)

Telephone triage was addressed by 11 studies;12–22 three were eligible for quality assessment.12,19,20 Four of the eleven studies concluded that telephone triage exerted little effect on A&E attendance.7,14,15,17 A Cochrane systematic review incorporating six studies of varying service configurations found no evidence of a significant reduction in A&E attendances, with one study (of nurse-led telephone triage) demonstrating an increase.12 The other systematic review considered telephone triage in the US and Canada; two of the three studies on telephone triage demonstrated significant reductions in A&E attendance,19 but this review was less methodologically robust than the Cochrane study. Evidence of a reduction in downstream workload is reported in terms of reduced demand for telephone advice obtained directly from A&E departments14 and out-of-hours GP services.12,17

Variations in the observed effect of telephone triage on A&E attendance rates may be attributable to various factors, including differences in triage service design. Studies covered interventions ranging from national telephone triage lines (for example, NHS Direct in the UK)16,17,20,21 to local advice lines14 and telephone services embedded within GP cooperatives.15 Several studies identified poor telephone triage design (for example, unclear clinical algorithms) as explanations for inappropriate A&E referral.14,15 The extent to which new services are integrated with pre-existing healthcare infrastructure, such as access to medical records, is also an important determinant of success.15,18

Patient mix may also be important. One study directly addressed this by examining contact rates for ‘frequent attendees’ across all urgent care services.22 This before–after intervention study showed a 16% reduction in contact rates for frequent attendees after a GP cooperative-based telephone triage service was introduced in Denmark. However, the authors did not address A&E attendance and excluded children (who account for 40% of all out-of-hours contacts).22 The findings of this Danish study have also been challenged by a systematic review of interventions in Canada and the US, which showed that telephone triage may trigger follow-up contacts, despite a reduction in same-day demand.19

Four studies considered patient outcomes. Of these, three examining clinical safety of telephone triage found adverse event and mortality rates comparable with, or better than, ‘standard’ care12,16,19 (comparable with, or better than, care provided in areas where telephone triage was not in operation). A descriptive evaluation of NHS Direct yielded an adverse event rate of 0.001% (no confidence interval [CI] given in the source manuscript), compared with 0.2–0.5% in other healthcare settings in the UK.16 Patient satisfaction with telephone triage was generally, but not universally, positive; one systematic review reported patient satisfaction rates of 55–90%,19 while the Cochrane review reported levels comparable with face-to-face services, albeit from surveys with response rates of 50%.12 A third study found satisfaction levels to be lower than face-to-face alternatives.23

The evidence on cost-effectiveness of telephone triage is limited and contradictory. One systematic review found statistically significant reductions in costs across the urgent care system following the introduction of telephone triage.19 A before–after study of a triage service targeting frequent attendees showed a 29% reduction in costs across the urgent care system. However, sensitivity analyses suggest that national triage services like NHS Direct may offset only 75% of their costs by redirecting patients; although economies of scale may be generated as services mature, the likelihood of savings across the urgent care system is low.16

Walk-in clinics, minor injuries units, and urgent care centres (n = 2)

The review found no studies addressing urgent care centres. Neither of the studies addressing walk-in clinics and minor injuries units24,25 were eligible for quality assessment, although two systematic reviews considering walk-in clinics among various other interventions were assessed.4,26 Both primary studies highlighted variation in walk-in clinic configuration around the UK.25

Retrospective analyses of A&E utilisation data suggest that 25–55% of attendees could have been treated by walk-in clinics or minor injuries units,27,28 but there is no evidence that such redirection occurs in practice where walk-in clinic or minor injuries unit services are available. A systematic review considering walk-in clinics showed no statistically significant reduction in A&E attendance following their introduction.4 This finding is supported by the majority of empirical work from the UK with one exception; a study in which a non-significant reduction in GP contact rates was reported.24 There may be some benefit in reducing repeat attendances: a systematic review 4 cites an interrupted time-series study of patients’ behaviour after first-time, low-acuity presentations to a walk-in clinic; it found that patients subsequently decreased their A&E usage by 48% (P<0.001).

Both studies of walk-in clinics and minor injuries units addressed patient outcomes.24,25 The UK-based study found no change in clinical outcome following the introduction of a walk-in clinic; many patients re-presented with their original complaints at both intervention and control sites. Studies of walk-in services in Canada and the US suggest that patient satisfaction is higher than with practice-based services because of convenience and shorter waiting times;26 however, these findings have not been replicated elsewhere.

One study considered the cost of introducing walk-in clinics.24 This before–after intervention study found that cost of care increased at both intervention and control sites, and that differences in cost were non-significant.

Community health centres (n = 2)

Neither of the studies addressing community health centres29,30 were eligible for quality assessment. Conducted in the US, both showed reductions in inappropriate attendances among individuals who were uninsured. One study found that patients at community health centres had fewer ‘preventable’ visits to A&Es and states that community health centres generate a 30% saving on annual Medicaid spending on A&E attendances in the US. However, no significance levels were provided and the methodology for this narrative review is unclear.30 The second study, a cross-sectional analysis of the impact of community health centres across a single state in the US, found a significant reduction (RR [relative risk] = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.11 to 1.59) in A&E attendance for ambulatory care-sensitive presentations in areas with community health centres, compared with those areas without.30

GP co-operatives and out-of-hours services (n = 11)

Eleven studies addressed GP cooperatives set up to provide out-of-hours care, the majority of which were before–after studies.31–39 None were eligible for quality assessment.

Evidence on the impact of GP cooperatives on A&E attendance is conflicting. One Irish study found a significant reduction in low-acuity attendances, following the introduction of a cooperative.34 However, the observation period coincided with a doubling of A&E co-payment fees for attendances, so it is unclear whether the reduction is attributable to the GP cooperative, to an increase in co-payment fees, or both. Two further before–after studies from The Netherlands reported reductions in A&E referral rates, particularly for musculoskeletal conditions, following the introduction of cooperatives.37,39 However, these studies were limited by their failure to control for seasonal variation37 and a lack of clarity on the statistical significance of their findings.

One Danish study reported a non-significant rise in A&E attendance following the introduction of a cooperative.40 None of the remaining studies found evidence of a significant reduction in A&E attendance rates following the introduction of GP cooperatives, and two did not address A&E attendance as an outcome measure.32,33

Patient-outcome measures were rarely considered. One Dutch before–after intervention study considered mortality and adverse event rates following the introduction of a cooperative; it showed rates that were comparable to other service providers.37 The only study looking at patient satisfaction (a before–after analysis from the UK) found no significant change.36

One Dutch study compared the cost of standalone GP cooperatives with those that were integrated with a hospital.40 There was no evidence of a reduction in costs across the healthcare system by housing cooperatives in dedicated facilities.

Emergency nurse practitioner (n = 1)

One Australian study examined the impact of emergency nurse practitioners in residential-care facilities providing first-line medical care for residents. This before–after intervention study was not eligible for quality assessment. The authors found a statistically significant reduction in A&E attendance from older care home residents (17%), controlling for seasonal variation. Reported satisfaction rates with the scheme from A&E doctors, health workers, and residential care staff was high, but cost data were not reported.41

DISCUSSION

Summary

Little high-quality evidence was found on the interventions considered in this review, that is, telephone triage systems, in- or ‘out-of-hours’ primary care provision and GP cooperatives, community health centres, walk-in clinics, minor injuries units, and urgent care centres; and no conclusive evidence was found to suggest that any of the interventions consistently reduce A&E attendance rates. For the two best-evidenced interventions, that is, telephone triage and out-of-hours GP care, an effect is demonstrated only for the former in reducing telephone calls made to A&E departments for advice. Although this may facilitate redistribution of staff to frontline clinical duties, the overall impact is likely to be small. The absence of clinical outcome and cost data from most analyses is striking and represents a major shortcoming in the evidence base.

Strengths and limitations

Work published before 1986 was excluded because of limited generalisability of findings from historical studies to modern-day health systems, but this may have led to some potentially relevant studies being overlooked. The methodological limitations of primary research studies in this area (most of which are ecological analyses of administrative data, without adjustment for variables including sex and socioeconomic status) imposed significant constraints. The few quasi-experimental studies included were poorly designed and used observation periods of insufficient length to adequately evaluate intervention impact. Direct comparison between interventions was complicated by inconsistencies in the outcome measures used.

Furthermore, included studies were undertaken across varied country and health system settings, ranging from tax-funded or social insurance systems with comprehensive primary care coverage (for example, The Netherlands and the UK) to private insurance systems, with variable primary care coverage (for example, the US), potentially confounding direct comparison.

It should also be noted that publication and selection bias pose challenges to validity in systematic reviews that address predominantly non-randomised studies. Variations in design and terminology make such studies hard to identify, so it is possible that some relevant studies were inadvertently excluded.

Comparison with existing literature

Access to primary care services in the urgent care sector is one of a complex array of interdependent determinants of A&E attendance. Although actual,30,42 or perceived,43 absence of primary care does result in increased emergency attendances, findings from this review support the notion that increasing access points for urgent care may unmask latent demand that is more likely to be inappropriate for A&Es. Cost savings across the urgent care sector as a whole may be negated by the additional cost of providing new services; in addition, there is a risk of service duplication with disruption to continuity of care because of provider proliferation. However, results from evaluations of new service models on A&E attendance in the UK (for example, urgent care centres) are still pending.44

Implications for practice

Findings from this review reinforce the idea that patient behaviour is an important determinant of A&E attendance, and merits further study. More generally, robust evaluations of primary care services in the urgent care sector are in short supply, partly because of the heterogeneity in operational and structural form of interventions. Cluster randomised trials of standardised services will be key to demonstrate that they are fit for purpose, improve access to healthcare, represent a sound investment of resources and, most importantly, improve health outcomes.

Appendix 1. SIGN quality ratings

| SIGN quality rating | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1++ | High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs or RCTs with a very low risk of bias |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a low risk of bias |

| 1– | Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a high risk of bias |

| 2++ | High-quality systematic reviews of case–control or cohort studies. High-quality case–control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2+ | Well-conducted case–control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2– | Case–control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal |

| 3 | Non-analytic studies, for example, case reports, case series |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

RCT = randomised controlled trial. SIGN = Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

Funding

Daniel Gibbons is a doctoral research fellow and is funded by the NHS National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The Department of Primary Care and Public Health at Imperial College London is grateful for support from NIHR’s Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Scheme, the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre scheme, and the Imperial Centre for Patient Safety and Service Quality.

Ethical approval

Not required for this study.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Blunt I, Bardsley M, Dixon J. Is greater efficiency breeding inefficiency? London: Nuffield Trust; 2010. Trends in Emergency Admissions in England 2004–2009. http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/publications/trends-emergency-admissions-england-2004-2009 [accessed 25 Oct 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Driscoll PA, Vincent CA, Wilkinson M. The use of the accident and emergency department. Arch Emerg Med. 1987;4(2):77–82. doi: 10.1136/emj.4.2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin A, Martin C, Martin PB, et al. ‘Inappropriate’ attendance at an accident and emergency department by adults registered in local general practices: how is it related to their use of primary care? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(3):160–165. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooke MW, Fisher J, Dale J, et al. Warwick: The University of Warwick; 2004. Reducing attendances and waits in emergency departments: a systematic review of present innovations Report to the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doobinin KA, Heidt-Davis PE, Gross TK, Isaacman DJ. Nonurgent pediatric emergency department visits: Care-seeking behavior and parental knowledge of insurance. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(1):10–14. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKee CM, Gleadhill DN, Watson JD. Accident and emergency attendance rates: variation among patients from different general practices. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(333):150–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy AW. ‘Inappropriate’ attenders at accident and emergency departments I: definition, incidence and reasons for attendance. Fam Pract. 1998;15(1):23–32. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roland M, Abel G. Reducing emergency admissions: are we on the right track? BMJ. 2012;345:e6017. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassan TB. Clinical decision units in the emergency department: old concepts, new paradigms, and refined gate keeping. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(2):123–125. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy AW, Bury G, Plunkett PK, et al. Randomised controlled trial of general practitioner versus usual medical care in an urban accident and emergency department: process, outcome, and comparative cost. BMJ. 1996;312(7039):1135–1142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7039.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS Plus and the Clinical Effectiveness Forum of the Royal College of Physicians . Grading systems and critical appraisal tools: A study of their usefulness to specialist societies. London: Royal College of Physicians and NHS Plus; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunn F, Byrne G, Kendall S. Telephone consultation and triage: effects on health care use and patient satisfaction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;18(4):CD004180. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004180.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunt D, Day SE, Kelaher M, Montalto M. Impact of standalone and embedded telephone triage systems on after hours primary medical care service utilisation and mix in Australia. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 2005;2:30. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-2-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graber DJ, Ardagh MW, O’Donovan P, St George I. A telephone advice line does not decrease the number of presentations to Christchurch Emergency Department, but does decrease the number of phone callers seeking advice. N Z Med J. 2003;116(1177):U495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lattimer V, Turnbull J, Burgess A, et al. Effect of introduction of integrated out of hours care in England: observational study. BMJ. 2005;331(7508):81–84. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7508.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munro J, Nicholl J, O’Cathain A, et al. Evaluation of NHS Direct first wave sites: Final report of the phase 1 research. Sheffield Medical Care Research Unit, University of Sheffield; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munro J, Sampson F, Nicholl J. The impact of NHS Direct on the demand for out-of-hours primary and emergency care. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(519):790–792. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shekelle P, Roland M. Nurse-led telephone-advice lines. Lancet. 1999;354(9173):88–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stacey D, Noorani HZ, Fisher A, et al. Telephone triage services: systematic review and a survey of Canadian call centre programs. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment; 2003. Technology Report No. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart B, Fairhurst R, Markland J, Marzouk O. Review of calls to NHS Direct related to attendance in the paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(12):911–914. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.039339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.South Wiltshire Out of Hours Project (SWOOP) Group Nurse telephone triage in out of hours primary care: a pilot study. BMJ. 1997;314(7075):198–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vedsted P, Olesen F. Frequent attenders in out-of-hours general practice care: attendance prognosis. Fam Pract. 1999;16(3):283–288. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leibowitz R, Day S, Dunt D. A systematic review of the effect of different models of after-hours primary medical care services on clinical outcome, medical workload, and patient and GP satisfaction. Fam Pract. 2003;20(3):311–317. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalder M, Sharp D, Moore L, Salisbury C. Impact of NHS walk-in centres on the workload of other local healthcare providers: time series analysis. BMJ. 2003;326(7388):532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7388.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salisbury C, Hollinghurst S, Montgomery A, et al. The impact of co-located NHS walk-in centres on emergency departments. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(4):265–269. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.042507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health Services Utilization and Research Committee . Reducing non-urgent use of the emergency department: a review of strategies and guide for future research. Saskatoon, SA: Health Services Utilization and Research Committee (HSURC); 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman P, Irons R, Nicholl J. Will alternative immediate care services reduce demands for non-urgent treatment at accident and emergency? Emerg Med J. 2001;18(6):482–487. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.6.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bickerton J, Davies J, Davies H, et al. Streaming primary urgent care: a prospective approach. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012;13(2):142–152. doi: 10.1017/S146342361100017X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choudhry L, Douglass M, Lewis J, et al. The impact of community health centers and community-affiliated health plans on emergency department use. Washington: Association for Community Affiliated Plans/National Association of Community Health Centers, Inc; 2007. http://www.nachc.com/client/documents/publications-resources/IB_EMER_07.pdf(accessed 6 Nov 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rust G, Baltrus P, Ye J, et al. Presence of a community health center and uninsured emergency department visit rates in rural counties. J Rural Health. 2009;25(1):8–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bury G, Dowling J, Janes D. General practice out-of-hours co-operatives–population contact rates. Ir Med J. 2006;99(3):73–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moll van Charante EP, van Steenwijk-Opdam PC, Bindels PJ. Out-of-hours demand for GP care and emergency services: patients’ choices and referrals by general practitioners and ambulance services. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;1(8):46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Keeffe N. The effect of a new general practice out-of-hours co-operative on a county hospital accident and emergency department. Ir J Med Sci. 2008;177(4):367–370. doi: 10.1007/s11845-008-0195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Kelly FD, Teljeur C, Carter I, Plunkett PK. Impact of a GP cooperative on lower acuity emergency department attendances. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(10):770–773. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.072686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philips H, Remmen R, De Paepe P, et al. Out of hours care: a profile analysis of patients attending the emergency department and the general practitioner on call. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pickin DM, O’Cathain A, Fall M, et al. The impact of a general practice co-operative on accident and emergency services, patient satisfaction and GP satisfaction. Fam Pract. 2004;21(2):180–182. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Uden CJ, Ament AJ, Voss GB, et al. Out-of-hours primary care. Implications of organisation on costs. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Uden CJ, Crebolder HF. Does setting up out of hours primary care cooperatives outside a hospital reduce demand for emergency care? Emerg Med J. 2004;21(6):722–773. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.016071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Uden CJ, Winkens RA, Wesseling G, et al. The impact of a primary care physician cooperative on the caseload of an emergency department: the Maastricht integrated out-of-hours service. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):612–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vedsted P, Christensen MB. The effect of an out-of-hours reform on attendance at casualty wards. The Danish example. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19(2):95–98. doi: 10.1080/028134301750235303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Codde J, Arendts G, Frankel J, et al. Transfers from residential aged care facilities to the emergency department are reduced through improved primary care services: an intervention study. Australas J Ageing. 2010;29(4):150–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2010.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arendts G, Reibel T, Codde J, Frankel J. Can transfers from residential aged care facilities to the Emergency Department be avoided through improved primary care services? Data from qualitative interviews. Australas J Ageing. 2010;29(2):61–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cowling TE, Cecil EV, Soljak MA, et al. Access to primary care and visits to emergency departments in England: a cross-sectional, population-based study. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e66699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gnani S, Ramzan F, Ladbrooke T, et al. Evaluation of a general practitioner-led urgent care centre in an urban setting: description of service model and plan of analysis. JRSM Short Rep. 2013;4(6):2042533313486263. doi: 10.1177/2042533313486263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]