Abstract

Background

Antidepressants are often the first-line treatment for depression in primary care. However, not all patients respond to medication after an adequate dose and duration of treatment. Currently, there are no estimates of the prevalence of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) from UK primary care.

Aim

To estimate the prevalence of TRD in UK primary care.

Design and setting

Data were collected as part of a multicentre randomised controlled trial, from 73 general practices in UK primary care.

Method

Potential participants (aged 18–75 years who had received repeated prescriptions for antidepressants) were identified from general practice records. Those who agreed to be contacted were mailed a questionnaire that included questions on depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI-II]), and adherence to antidepressants. Those who scored ≥14 on the BDI-II and had taken antidepressants for at least 6 weeks at an adequate dose were defined as treatment resistant.

Results

A total of 2439 patients completed the questionnaire (84% of those who agreed to be contacted), of whom 2129 had been prescribed an adequate dose of antidepressants for at least 6 weeks. Seventy-seven per cent (95% CI = 75% to 79%) had a BDI score of ≥14. Fifty-five per cent (95% CI = 53% to 58%) (n = 1177) met the study’s definition of TRD, of whom 67% had taken their antidepressants for more than 12 months.

Conclusion

The high prevalence of TRD is an important challenge facing clinicians in UK primary care. A more proactive approach to managing this patient population is required to improve outcome.

Keywords: antidepressants, prevalence, primary health care, treatment resistant depression

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a disabling condition and the third most common reason for consulting a GP in the UK.1 Moderate and severe depression in UK primary care is often treated with antidepressants and there has been a steady rise in antidepressant prescribing in the UK in recent years.2,3 However, not all patients respond adequately to antidepressants,4 and there is concern about the impact on both patients and society for those whose symptoms do not respond to such treatment.

In considering the ‘next-step’ for those who have not responded to medication, it is important to distinguish between non-response attributable to non-adherence to treatment (either non-adherence to medication or not returning for follow-up in primary care) and treatment resistance (where an adequate dose and duration of treatment has been given). However, there is no single definition of what constitutes ‘treatment resistance’.5 Definitions range from failure to respond to 4 weeks of antidepressant medication,6 to more complex classification systems based on non-response to a number of different medications.7 Much of the cost and disability associated with depression is accounted for by treatment resistance.8,9 Yet, there are few estimates of the prevalence of treatment-resistant depression (TRD).

The large STAR*D study from the US found that more than half of all patients recruited through primary care and psychiatric clinics did not achieve remission after first-line antidepressant treatment, and 33% did not experience remission after four courses of short-term treatment.10 A European study (GSRD) found that 50.7% of depressed patients recruited from specialist referral centres were considered treatment resistant after two consecutive courses of treatment with antidepressants.11 These data suggest that non-response to medication after antidepressant treatment is a substantial problem. However, there are currently no data for UK primary care and it is unclear whether the above figures would generalise to the UK setting. Given the high prevalence of depression among patients presenting to primary care, accurate estimates of non-response to antidepressant treatment are important to determine whether there is unmet need. The CoBalT study (Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in primary care) provides an opportunity to estimate the prevalence of TRD among those prescribed antidepressants for at least 6 weeks in UK primary care.

How this fits in

Antidepressants are commonly prescribed for the treatment of depression but not all patients respond to medication. There are currently no estimates of the prevalence of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in UK primary care. Using data collected as part of the CoBalT multicentre randomised controlled trial, this study estimated that the prevalence of TRD in UK primary care was 55% (95%CI = 53% to 58%). The high prevalence of TRD is an important challenge facing clinicians, and a more proactive approach to the management of this patient population is required in order to improve outcomes.

METHOD

The data for this study were collected during the initial stage of CoBalT, a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) that examined the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), given in addition to usual care (including antidepressants), compared with usual care alone, in primary care patients with depression that had not responded to antidepressant treatment.

In total, 106 general practices across the three centres (Bristol, Exeter, and Glasgow) were invited to collaborate. Eighty-eight practices agreed and record searches were conducted at 73 practices. The average (median) list size for the 73 participating practices was 7400 (interquartile range 4286–10 368), with an average of 4.5 full-time GPs in each practice (standard deviation 2.6). Full details of the study are available elsewhere.12

Identification of participants

A search of computerised records was conducted at the collaborating GP practices, to identify patients aged 18–75 years who had received repeated prescriptions for antidepressants (at an adequate dose for depression,13) during the previous 4 months. GPs excluded individuals with bipolar disorder, psychosis, or severe alcohol or substance use problems, as well as those unable to complete the study questionnaires or for whom the study was regarded as inappropriate (for example, patients who were terminally ill). Patients who were receiving CBT or other psychotherapy (or who had had CBT in the last 3 years) were also excluded. The remaining patients were mailed an invitation letter and information sheet about the study and asked to respond indicating whether they were/were not willing to be contacted by the research team.

Anonymised data on age and sex of patients, who were mailed an invitation to participate but who did not respond, were collected to assess the generalisability of the study findings.

Questionnaire

Patients who agreed to participate were mailed a screening questionnaire. This included a validated self-report measure of depressive symptoms, the Beck Depression Inventory — version two (BDI-II),14 which has been widely used for research purposes. The questionnaire also asked about current antidepressant medication, including duration of treatment and adherence to antidepressants. The latter was assessed using the Morisky scale,15,16 with an additional item added to ensure that individuals who had missed fewer than two consecutive doses were not excluded.

Data on sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, educational qualifications, employment status, housing situation, and financial situation) were also collected.

Defining treatment resistance

Given the lack of consensus in the definition of TRD,5 an inclusive definition was proposed, relevant to UK primary care.17 Treatment resistance was defined as those patients who scored ≥14 on the BDI-II, and who had been taking antidepressant medication at an adequate dose, for at least 6 weeks. A score of ≥14 on the BDI-II indicates the presence of at least mild depressive symptoms.

Dataset

As well as recruiting participants via a record search, GPs were able to refer patients directly to researchers. For this analysis, such individuals (n = 37) were excluded. In addition, for those individuals who were re-screened to ascertain eligibility for the trial, data from their first postal questionnaire was used. Thus, the estimates of prevalence are based on data obtained from one search of patient records from all participating practices.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in Stata (version 11.2). The prevalence of TRD was estimated with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), adjusting for clustering by GP practice. The impact of non-response (to the initial study invitation and screening questionnaire) on estimates of prevalence was assessed using probability weights (inverse of the non-response rate for each GP practice) such that data from practices with higher response rates were given more weight. Weighted estimates of prevalence were calculated using the survey commands in Stata (svy commands). Technical limitations mean that it was not possible to adjust the latter estimates for clustering by GP practice; however, preliminary analyses showed that there was little evidence of clustering by GP practice.

Descriptive data on the type of antidepressant medication taken by those fulfilling the present definition of TRD are reported, including the number on combined (defined as two different antidepressant medications at an adequate dose) or augmented treatment (with a non-antidepressant medication). Sociodemographic characteristics were compared for those with TRD, those not adhering to medication and those who had minimal depressive symptoms. Age and sex were compared for those who did or/did not participate.

RESULTS

Response to study invitation and questionnaire completion

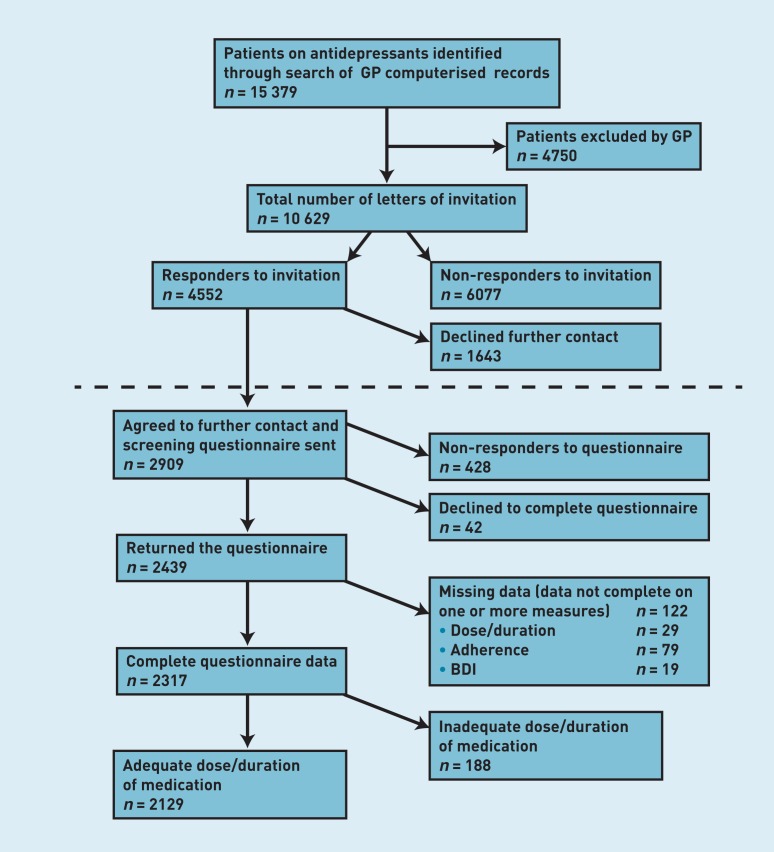

In total, 10 629 patients were mailed an invitation letter, of whom 4552 (43%) responded (Figure 1). Of these, 64% agreed to being sent a questionnaire, and subsequently, most (n = 2439, 84%) returned a completed questionnaire (Figure 1) giving an overall response rate of 23%.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the CoBalT study recruitment process. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory.

Of those who returned a questionnaire, complete data on dose and duration of antidepressant treatment and depressive symptoms were available for 2317 participants (95%). Of these, 8.8% were not taking an adequate dose of medication, or had been taking medication for less than 6 weeks, and were excluded from further analyses. This gave a sample of 2129 patients in whom to estimate the prevalence of TRD (Figure 1).

Data on age and sex were available for most of those who were mailed an invitation and compared for participants and non-participants (those who did not respond to the invitation: n = 6077; and those who responded but who declined to participate: n = 1643). There were no differences in age between those who returned a completed questionnaire (participants) and those who did not (Table 1). However, females were more likely to participate than males (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of age and sex for those who did or did not participate in the CoBalT study

| Participants n = 2909 | Non-participants n = 7720 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| na | Mean | SD | na | Mean | SD | P-value | |

|

|

|

||||||

| Age | 2746 | 48.2 | 13.5 | 7375 | 47.8 | 13.6 | 0.129 |

|

| |||||||

| na | n | % | na | n | % | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| Sex (female) | 2821 | 2020 | 71.6 | 7580 | 5166 | 68.2 | <0.001 |

Data on age and sex were not available for all.

Prevalence of treatment resistant depression

Among the 2129 patients (prescribed an adequate dose of antidepressant medication for at least 6 weeks), 1635 (77%, 95% CI = 75% to 79%) had a BDI-II score of ≥14. Overall, 55% met the study’s definition of TRD (Table 2). Twenty-two per cent had a BDI-II score of ≥14 but had not adhered to medication, and 23% had minimal symptoms of depression (BDI-II score <14) (Table 2). Of those with minimal symptoms, most (n = 401; 81%, 95% CI = 78% to 84%) had adhered to their medication.

Table 2.

Prevalence of treatment-resistant depression

| n | % | 95% CIa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDI ≥ 14 and adhered to medication (TRD) | 1177 | 55.3 | 52.8 to 57.8 |

| BDI ≥ 14 but had not adhered to medication | 458 | 21.5 | 19.4 to 23.6 |

| BDI < 14 (minimal symptoms) | 494 | 23.2 | 20.9 to 25.5 |

CIs have been adjusted for clustering by GP practice. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory. TRD = treatment-resistant depression.

Given the non-response to the study invitation and subsequently to the postal questionnaire, the study examined the impact on estimates of prevalence. The response rate (for the study invitation and screening questionnaire) varied between 8% and 50% for the 73 practices. Response rate was negatively correlated with prevalence of TRD (Pearson’s correlation coefficient r = 0.43, P<0.001) and positively correlated with prevalence of minimal depressive symptoms (BDI-II <14) (r = 0.31, P<0.01) for the 73 practices. However, estimates of prevalence weighted for non-response differed little from the figures reported above (weighted prevalence of TRD: 54.7% [95% CI = 52.2% to 57.2%]; non-adherers: 21.6% [95% CI = 19.5% to 23.7%]; minimal symptoms: 23.7% [95% CI = 21.4% to 26.0%]).

Antidepressant medication

Among those with TRD, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were the most common type of antidepressant (79%) (Table 3). Citalopram and fluoxetine accounted for 67% of all antidepressants prescribed, in line with prescribing figures for England for 2011.18 Most patients were taking one antidepressant (monotherapy), with less than 2% of those with TRD receiving combined treatment. Augmented antidepressant treatment was very rare (Table 3). A further 57 patients were taking a second antidepressant medication, but at a dose below the study’s definition of ‘adequate’.

Table 3.

Prescribed antidepressant medication among patients with treatment-resistant depression

| Antidepressant | Dose, mg | Class | n | % | % of ADs issued in England in 2011a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | 20–80 | SSRI | 448 | 38.0 | 28.9 |

| Fluoxetine | 20–80 | SSRI | 334 | 28.3 | 11.8 |

| Venlafaxine | 75–450 | SNRI | 93 | 7.9 | 5.9 |

| Mirtazapine | 30–60 | Other | 82 | 6.9 | 8.3 |

| Paroxetine | 20–60 | SSRI | 73 | 6.2 | 3.3 |

| Sertraline | 100–400 | SSRI | 39 | 3.3 | 7.8 |

| Escitalopram | 10–40 | SSRI | 25 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| Lofepramine | 140–350 | TCA | 24 | 2.0 | 0.7 |

| Dosulepin | 150–225 | TCA | 9 | 0.8 | 3.3 |

| Trazodone | 150–300 | TCA-related | 8 | 0.7 | 2.1 |

| Duloxetine | 60–90 | SNRI | 8 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| Amitriptyline | 150–200 | TCA | 6 | 0.5 | 20.5 |

| Reboxetine | 8–12 | NaRI | 3 | 0.3 | 0.09 |

| Other ADsb | Variable | Variable | 4 | 0.4 | 1.3 |

| Combined treatmentc | 19 | 1.6 | |||

| Augmented treatmentd | 2 | 0.2 |

Data taken from England prescribing data 2011, https://catalogue.ic.nhs.uk/publications/prescribing/primary/pres-cost-anal-eng-2011/pres-cost-anal-eng-2011-rep.pdf.

Other ADs: clomipramine (TCA), imipramine (TCA), moclobemide (MAOI), trimipramine (TCA).

Combined treatment: patients taking two antidepressant medications at an adequate dose.

Augmented treatment: patients taking another non-antidepressant medication along with their antidepressant, to augment their depression treatment. AD = antidepressant. SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. SNRI = serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. TCA = tricyclic antidepressant. NaRI = noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

Characteristics of patients with treatment resistant depression

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were compared for those with TRD, for those who had significant depressive symptoms but had not adhered to their medication (not adherent), and for those with minimal symptoms (Table 4). Differences were evident for a number of variables but tended to reflect differences between those with minimal symptoms compared with the other two groups. For example, those with minimal symptoms were more likely to be married, working (full-/part-time), and were less likely to be living in rented accommodation or experiencing financial difficulty than the other two groups (P<0.001 for all comparisons) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of patients with treatment-resistant depression compared with those not adhering to medication and those with minimal symptoms.

| All (n = 2129) | TRD (BDI score ≥14 and adhering to medication) (n = 1177) | Not adherent (BDI score ≥14 and not adhering to medication) (n = 458) | Minimal symptoms (BDI score < 14) (n = 494) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 48.5 (13.4) | 49.6 (12.7) | 43.0 (12.8) | 50.9 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Sex: female, n (%) | 1474 (71.3) | 815 (70.3) | 311 (70.8) | 348 (74.0) | 0.310 |

| Married/living as married, n (%) | 1 113 (52.9) | 622 (53.3) | 193 (42.9) | 298 (60.9) | <0.001 |

| BDI score, mean (SD)b | 24.6 (13.5) | 29.1 (10.4) | 32.0 (10.6) | 7.0 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Duration of current AD use, n (%)b | |||||

| 6 weeks–6 months | 328 (15.4) | 187 (15.9) | 71 (15.5) | 70 (14.1) | 0.400 |

| 6 months–1 year | 347 (16.3) | 199 (16.9) | 79 (17.3) | 69 (14.0) | |

| >1 year | 1454 (68.3) | 791 (67.2) | 308 (67.2) | 355 (71.9) | |

|

| |||||

| Socioeconomic indicators | |||||

| Educational qualifications, n (%) | |||||

| A level or higher | 1047 (49.9) | 559 (48.1) | 197 (44.0) | 291 (59.8) | <0.001 |

| GCSE/other | 570 (27.2) | 317 (27.3) | 147 (32.8) | 106 (21.8) | |

| No qualifications | 479 (22.9) | 285 (24.6) | 104 (23.2) | 90 (18.5) | |

| Working (full- or part-time), n (%) | 970 (46.1) | 487 (41.8) | 191 (42.4) | 292 (59.8) | <0.001 |

| Housing tenure (rented/other), n (%) | 927 (44.0) | 533 (45.6) | 261 (58.0) | 133 (27.1) | <0.001 |

| Finances: just getting by/difficult, n (%) | 1150 (54.6) | 715 (61.2) | 320 (71.3) | 115 (23.5) | <0.001 |

Comparison between groups using t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

Variables with complete data. There are missing data for the other sociodemographic variables: age total n = 2004; sex total n = 2068; marital status total n = 2106; education total n = 2096; employment status total n = 2104; housing tenure total n = 2109; financial situation total n = 2108. GCSE = General Certificate of Secondary Education. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory. TRD = treatment-resistant depression.

Sixty-eight per cent of patients had been taking their current antidepressant for more than 12 months. This was a consistent finding among the three groups of patients described: those with TRD (67.2%); those who were non-adherent to their antidepressants (67.2%); with the figure for those with minimal symptoms being slightly higher (71.9%) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Summary

More than three-quarters of primary care patients taking antidepressants for at least 6 weeks had significant depressive symptoms. Fifty-five per cent of patients who had taken an adequate dose of antidepressant medication for at least 6 weeks were classified as having TRD, clearly demonstrating that inadequate response to antidepressant medication is an important problem in UK primary care. Most patients (68%) reported having taken their current medication for more than 12 months. This highlights the chronic nature of depression among many of those treated in primary care, and gives rise to concern about systematic reassessment and treatment of those on long-term antidepressants.

In general, the frequency of the different types of antidepressant taken by those with TRD aligned with national prescribing data for England.18 Amitriptyline was frequently prescribed at low doses (not regarded as an effective therapeutic dose for depression), accounting for the lower ranking of this medication among those with TRD in the sample. Venlafaxine was slightly more frequently used compared with national prescribing data,18 perhaps indicating that GPs had initially prescribed an SSRI in line with NICE recommendations for treating depression, switching to venlafaxine as an alternative because of a lack of response.

Strengths and limitations

Data from the recruitment phase of a large RCT based in UK primary care were used. The large number of practices covering urban, rural, and semi-rural settings across the three centres (Bristol, Exeter, and Glasgow) enabled estimation of a figure for the prevalence of TRD in UK primary care with comparatively narrow confidence intervals.

Unlike other studies such as STAR*D,10 this study distinguished between non-response and non-adherence to medication in defining the treatment-resistant group. Non-adherence to medication is known to be common in depressed patients,19 but is notoriously difficult to measure. Other studies have relied on clinician report to gather this information,11 and yet it has been reported that patients have difficulty being honest with health professionals about whether they are taking their medication as prescribed.20 The present study relied on a self-report measure of medication use15 that has been validated against electronic monitoring bottles.16

There are a number of limitations to this study, the key issue being the low response rate. Only 43% of those invited to participate responded to the letter from the GP, with 54% subsequently returning a completed postal questionnaire, which gave an overall response rate of 23%. Present estimates of prevalence may be biased by this non-response, and this possibility cannot be eliminated. However, there was no difference in estimates of prevalence that were or were not weighted for non-response by practice, suggesting that present estimates are relatively unaffected by this problem. Furthermore, although females were more likely to respond to the invitation to participate, there is no evidence that females were more or less likely to have TRD, so it is unlikely that these estimates are biased by non-response.

The present data are cross-sectional and the authors acknowledge that individuals may have experienced a change in their depressive symptoms between the time of the initial prescription and questionnaire completion. Therefore, potentially some individuals may have shown some rather than no response to medication. Nonetheless, their BDI scores indicated that they continued to have significant depressive symptoms. A longitudinal study of patients starting a new antidepressant could help make finer distinctions in terms of defining treatment responders, partial responders, and non-responders. Further, although the BDI-II measures severity of depressive symptoms, it is not a diagnostic instrument. Nonetheless, those with TRD had a mean BDI-II score of 29.1, which is indicative of severe depression.

As highlighted earlier, there are many definitions of treatment resistance. The definition of TRD used in the CoBalT study is pragmatic and directly relevant to UK primary care, given the uncertainty about what treatments to recommend to those who do not respond after 4–6 weeks of antidepressant medication.17

Comparison with existing literature

Reports suggest that managing TRD is an area that has been poorly investigated, with very few robust data to guide treatment.21–23 Although non-response to antidepressants is frequently cited as a key issue in managing patients with depression, few studies have quantified the magnitude of this problem and no evidence exists for UK primary care. Estimates of the prevalence of TRD range from 30%10 to 50%.11 The present estimate of 55% is at the upper end of this range. It is difficult to compare the estimates of prevalence between studies directly because of differing definitions of treatment resistance, including whether or not diagnostic criteria have been applied to identify those with depression,10,11 and whether patients have been included from psychiatric clinics as well as from primary care. Nonetheless, the present data clearly demonstrate that TRD represents a significant burden for patients and primary care clinicians in the UK.

Implications for research and practice

This evidence of the scale of inadequate response to antidepressants in UK primary care is worrying, particularly in the context of the continued increase in prescribing. Little is known about the treatment received by patients with depression after an antidepressant has been prescribed. It is not clear what constitutes usual care. Although the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) has incentivised primary care clinicians to record the severity of depressive symptoms at the start of treatment (DEP6) and again within 12 weeks (DEP7), no incentives are in place with respect to longer-term management.24 A substantial proportion of patients may receive long-term antidepressants without being adequately assessed for treatment response. It is important to identify those who continue to have significant depressive symptoms through regular reviews so that patients and clinicians can discuss alternative treatment options. The present data suggest that the NICE guidelines17 for sequencing treatments after initial inadequate response are not widely followed as there is very little evidence in the present sample of combining or augmenting antidepressant treatments.

Given the lack of motivation that is common among patients with depression, it has been suggested that a more proactive clinician-led approach to managing this patient population could be of benefit.25 The authors would urge repeated monitoring of symptoms, together with recording of medication adherence, at regular reviews. Such an approach may help identify those patients whose symptoms have not responded to medication at an earlier stage when it might be possible to intervene to prevent chronicity and to improve patient outcome.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients, practitioners and GP surgery staff who took part in this research, and acknowledge the additional support of the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN), Scottish Mental Health Research Network (SMHRN), Primary Care Research Network (PCRN), and Scottish Primary Care Research Network (SPCRN). We thank those colleagues who contributed to the CoBalT study. Finally, we are grateful to colleagues who were involved with the CoBalT study as co-applicants: Sandra Hollinghurst, Bill Jerrom, Willem Kuyken, Debbie Sharp, and Katrina Turner.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) programme (project number: 06/404/02). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HTA programme, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from West Midlands Research Ethics Committee (ref 07/H1208/60) and research governance approval from Bristol, South Gloucestershire, North Somerset, Devon, and Plymouth Teaching Primary Care Trusts and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Community and Mental Health Partnership. The trial is registered under ISRCTN38231611.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

Chris Williams has been a past president of the CBT organisation British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP), a workshop leader and author of texts and websites on depression and self-help resources. The other authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O’Brien M, Lee A, Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000 (Reprinted from Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000: Summary report, 2001) Int Rev Psych. 2003;15(1–2):65–73. doi: 10.1080/0954026021000045967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health and Social Care Information Centre (Prescribing and Primary Care Services) Prescriptions Dispensed in the Community: Statistics for England — 2001 to 2011. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB06941 (accessed 4 Nov 2013)

- 3.National Services Scotland. Information Services Division. Prescribing & Medicines: Medicines for Mental Health — Financial Years 2002/03 to 2011/12. 2012. https://isdscotland.scot.nhs.uk/Health-Topics/Prescribing-and-Medicines/Publications/2012-09-25/2012-09-25-PrescribingMentalHealth-Report.pdf?18890017272 (accessed 12 Nov 2013)

- 4.Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berlim MT, Turecki G. What is the meaning of treatment resistant/refractory major depression (TRD)? A systematic review of current randomized trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(11):696–707. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Psychiatric Association Symposium on therapy resistant depression. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thase ME, Rush AJ. When at first you don’t succeed: Sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crown WH, Finkelstein S, Berndt ER, et al. The impact of treatment-resistant depression on health care utilization and costs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(11):963–971. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Kidolezi Y, et al. Direct and indirect costs of employees with treatment-resistant and non-treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(10):2475–2484. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.517716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiat. 2006;163(11):1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: Results from a European multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(7):1062–1070. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas LJ, Abel A, Ridgway N, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment resistant depression in primary care: The CoBalT randomised controlled trial protocol. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(2):312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiles N, Thomas L, Abel A, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care based patients with treatment resistant depression: results of the CoBalT randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9864):375–384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. 2nd Edn. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George CF, Peveler RC, Heiliger S, Thompson C. Compliance with tricyclic antidepressants: the value of four different methods of assessment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50(2):166–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) The treatment and management of depression in adults Nice Clinical Practice Guideline 90. London: NICE; 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/cg90niceguideline.pdf (accessed 4 Nov 2013) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Health and Social Care Information Centre (Prescribing and Primary Care Services) Prescription Cost Analysis: England. 2011. The NHS Information Centre, 2012.

- 19.DiMatteo M, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Int Med. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter S, Taylor D, Levenson R. A question of choice — compliance in medicine-taking. A preliminary review. London: Medicines Partnership; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connolly KR, Thase ME. If at first you don’t succeed: a review of the evidence for antidepressant augmentation, combination and switching strategies. Drugs. 2011;71(1):43–64. doi: 10.2165/11587620-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stimpson N, Agrawal N, Lewis G. Randomised controlled trials investigating pharmacological and psychological interventions for treatment-refractory depression. Systematic review. Br J Psychiat. 2002;181:284–294. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.4.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McPherson S, Cairns P, Carlyle J, et al. The effectiveness of psychological treatments for treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111(5):331–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.BMA and NHS Employers Quality and outcomes framework for 2012/13: Guidance for PCOs and practices. 2012. http://www.nhsemployers.org/Aboutus/Publications/Documents/QOF_2012-13.pdf (accessed 12 Nov 2013)

- 25.Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression: a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiat. 2009;70:26–31. doi: 10.4088/JCP.8133su1c.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]