Abstract

Background

The factors that lead to patients failing multiple anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions are not well understood.

Hypothesis

Multiple-revision ACL reconstruction will have different characteristics than first-time revision in terms of previous and current graft selection, mode of failure, chondral/meniscal injuries, and surgical charactieristics.

Study Design

Case-control study; Level of evidence, 3.

Methods

A prospective multicenter ACL revision database was utilized for the time period from March 2006 to June 2011. Patients were divided into those who underwent a single-revision ACL reconstruction and those who underwent multiple-revision ACL reconstructions. The primary outcome variable was Marx activity level. Primary data analyses between the groups included a comparison of graft type, perceived mechanism of failure, associated injury (meniscus, ligament, and cartilage), reconstruction type, and tunnel position. Data were compared by analysis of variance with a post hoc Tukey test.

Results

A total of 1200 patients (58% men; median age, 26 years) were enrolled, with 1049 (87%) patients having a primary revision and 151 (13%) patients having a second or subsequent revision. Marx activity levels were significantly higher (9.77) in the primary-revision group than in those patients with multiple revisions (6.74). The most common cause of reruptures was a traumatic, noncontact ACL graft injury in 55% of primary-revision patients; 25% of patients had a nontraumatic, gradual-onset recurrent injury, and 11% had a traumatic, contact injury. In the multiple-revision group, a nontraumatic, gradual-onset injury was the most common cause of recurrence (47%), followed by traumatic noncontact (35%) and nontraumatic sudden onset (11%) (P < .01 between groups). Chondral injuries in the medial compartment were significantly more common in the multiple-revision group than in the single-revision group, as were chondral injuries in the patellofemoral compartment.

Conclusion

Patients with multiple-revision ACL reconstructions had lower activity levels, were more likely to have chondral injuries in the medial and patellofemoral compartments, and had a high rate of a nontraumatic, recurrent injury of their graft.

Keywords: ACL, ACL revision, allograft, autograft

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is one of the most common orthopaedic procedures performed, with the goal of restoring anterior-posterior and rotational stability to the knee. It is generally a successful procedure that restores stability of the knee and allows patients to return to athletic activities.14 However, a small but significant subset of ACL reconstructions fail, and those patients have a lower rate of return to sports as well as an increased likelihood of meniscal and chondral injuries.5 In addition, clinical outcomes after revision reconstruction are worse than those after primary ACL reconstruction.18,22,24

Many characteristics are thought to be important in determining the outcomes of ACL reconstruction, and these factors can be magnified in patients with multiple ACL revisions. Epidemiological factors including age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) have been suggested to have a role in graft failure and outcome.1,2 Graft selection has also been demonstrated to have a difference in failure rates, especially in young patients.13 Tunnel malposition, a leading cause of ACL graft failure, can result in graft loosening and atraumatic failure of the ACL reconstruction.19 In addition, the Multicenter ACL Revision Study (MARS) group reported that 90% of knees undergoing revision ACL reconstruction had meniscal or chondral injuries and that a previous partial meniscectomy was associated with a higher incidence of articular cartilage lesions.6 Thus, it stands to reason that those patients with multiple ACL reconstructions will have a higher rate of articular and meniscal lesions.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate differences in demographics, intraoperative findings, and mechanisms of failure between patients who had undergone a single-revision ACL reconstruction and those who had undergone multiple-revision ACL reconstructions and to evaluate surgical characteristics between these 2 groups. We hypothesized that multiple-revision ACL reconstructions would have different characteristics than first-time revisions in terms of previous and current graft selection, mechanism of failure, and presence of chondral/meniscal injuries and that those in the multiple-revision group would have lower activity levels.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The MARS study is a prospective, longitudinal cohort design with multiple sites (n = 52) and multiple surgeons (n = 87) that was undertaken to evaluate a large cohort of patients undergoing revision ACL reconstruction. This cohort study is sponsored by the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) and was designed to recruit and retain enough patients with longitudinal follow-up to allow analyses of factors affecting outcome. The study design and rationale have been previously described23 and utilized in subsequent research studies.5,6 Surgeons participating in the study were required to attend training sessions to discuss operating procedures and items for data collection. To establish standardization and uniformity among the group, all study-related forms were reviewed in detail, and all questions were answered regarding how to appropriately complete them. Meniscal and articular cartilage arthroscopy videos were also reviewed, independently graded by each physician, and then discussed by the group to clarify any ambiguity in the classification of meniscal and articular cartilage injuries.

Data from the MARS cohort were reviewed to compare differences between patients who had undergone a single-revision ACL reconstruction and those who had undergone multiple-revision ACL reconstructions. Patient enrollment began in March of 2006, and the cohort in this study included enrollment through June 2011. Inclusion criteria for this study were patients who were currently identified as having experienced a failure of their ACL reconstruction, as defined by the surgeon by anterior knee laxity (5-mm side-to-side difference on KT-1000 arthrometer testing with a 30-lb load), a positive pivot-shift or Lachman test result, functional instability, and/or magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopic confirmation. Patients with concomitant injuries to the medial and lateral collateral ligaments, posterior cruciate ligament, or posterolateral complex were also included. Exclusion criteria for the study were patients with graft failure secondary to a prior intra-articular infection, arthrofibrosis, or complex regional pain syndrome. Patients unwilling or unable to complete their repeat questionnaire 2 years after their initial visit were also excluded.

Outcome Variables

The primary outcome variables were the presence of meniscal and cartilage injuries, mechanism of failure, and graft type at the time of injury and reconstruction. The revising surgeon inputted data at the time of the procedure. Information was obtained from previous primary ACL surgery operative notes (if they could be obtained), the patient questionnaire, and intraoperative findings at the time of ACL revision surgery. Demographic data included age, sex, and BMI. Graft type was recorded as autograft (hamstring, bone–patellar tendon–bone [BPTB]) or allograft (soft tissue, BPTB, Achilles). The mechanism of failure was recorded as traumatic contact, traumatic noncontact, or nontraumatic (sudden or gradual onset) based on the report of the patient. The underlying cause of the failure was at the discretion of the treating surgeon and was described with primary variables: technical (poor tunnel placement, poor fixation technique, missed associated injury), biological, or traumatic. Within these categories, a secondary cause of failure can be listed as well. For instance, a patient could have poor tunnel placement (technical error) as well as a traumatic injury that caused the recurrent ACL tear. Tunnel position was not quantified for the purposes of this study but was qualitatively described by the treating surgeon as acceptable or not acceptable. Management of the tibial and femoral tunnels was recorded as using the same tunnel (in an optimal or compromised position), a new tunnel, or a blended tunnel in which the tunnels converge. Less commonly, the surgeons performed a double-bundle augmentation (second tunnel), an over-the-top graft technique, or a modification of this. The presence of bone grafting of either the femoral or tibial tunnel was also recorded.

Meniscal lesions were evaluated at the time of surgery, and treatment was divided into debridement, repair, transplant, and no treatment. The medial and lateral menisci were evaluated separately. Classification of the general knee examination findings followed the recommendations of the updated 1999 International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) guidelines.11,12 Surgeon documentation of articular cartilage injury was recorded according to the modified Outerbridge classification8 and was based on an interobserver agreement study.15 Finally, the status and treatment of the medial and lateral collateral ligaments were described. The Marx activity scale was the primary clinical outcome score utilized to compare groups.16

Statistics

Data are reported as the number of patients (percentage of group). Significance was set with a P value <.05 and is reported in the text. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc correction was used to compare data between the primary-revision and multiple-revision groups. Multi-variate regression was used to control for variables including age, sex, and BMI as well as possible confounders such as previous meniscal tears or cartilage injuries. Data analysis was performed with SPSS software version 15.1 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

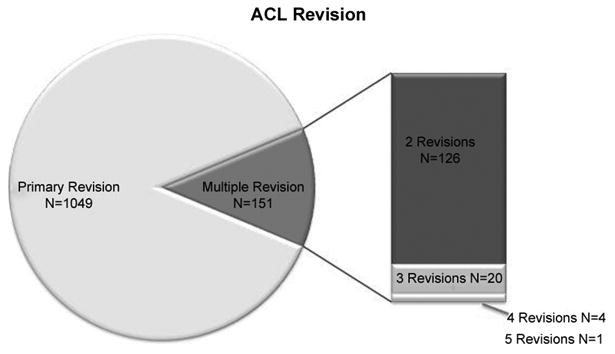

As of June 2011, MARS had enrolled 1200 patients: 1049 (87%) primary-revision and 151 (13%) multiple-revision patients (Table 1). The number of total revisions among the multiple-revision patients was distributed as follows: 126 (83.4%) with 2 prior, 20 (13.2%) with 3 prior, 4 (2.6%) with 4 prior, and 1 (0.7%) with 5 prior revisions (Figure 1). The mean age of the patients in the primary-revision group (27.7 years; range, 12-63 years) differed significantly from those patients with multiple revisions (29.6 years; range, 14-63 years) (P = .02). The mean BMI of the patients in the primary-revision group (26.0; range, 17-47) did not differ significantly from those patients with multiple revisions (26.5; range, 18-47). Patient sex did not differ significantly between the groups, with approximately 60% being male. Current Marx activity levels were significantly higher (9.77; range, 0-16) in the primary-revision group compared with those patients with multiple revisions (6.74; range, 0-16) (P = .036).

Table 1. Baseline Patient Dataa.

| Description | Primary-Revision ACLR | Multiple-Revision ACLR | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean | 27.7 | 29.6 | .03 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 602 (57.4) | 93 (61.5) | .01 |

| Body mass index, mean | 26 | 26.5 | .38 |

| Marx activity level, mean | 9.77 | 6.74 | .04 |

| Mechanism of injury, n (%) | |||

| Nontraumatic, gradual onset | 266 (25) | 71 (47) | <.01 |

| Nontraumatic, sudden onset | 67 (6) | 17 (11) | .04 |

| Traumatic, contact | 134 (13) | 10 (7) | <.01 |

| Traumatic, noncontact | 579 (55) | 53 (35) | <.001 |

| Prior ACL graft, n (%) | |||

| Allograft | 263 (25) | 82 (54) | <.01 |

| Autograft | 772 (74) | 43 (28) | <.01 |

| Allograft and autograft | 5 (<1) | 23 (15) | <.001 |

| Combined (with prosthetic) | 7 (<1) | 3 (2) | NS |

| Cause of ACL failure, n (%) | |||

| Traumatic, isolated | 371 (35) | 30 (20) | <.01 |

| Biological and traumatic | 49 (5) | 9 (6) | NS |

| Technical error and traumatic | 169 (16) | 13 (9) | <.05 |

| Combination/other and traumatic | 27 (3) | 3 (2) | NS |

| Technical error, isolated | 219 (21) | 44 (29) | <.01 |

| Biological failure to heal and technical error | 111 (11) | 28 (19) | <.05 |

| Infection/other and technical error | 8 (<1) | 2 (1) | NS |

| Biological failure to heal (isolated) | 80 (8) | 17 (11) | NS |

| Other and biological failure to heal | 5 (<1) | 3 (2) | NS |

| Infection (isolated) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Other | 8 (<1) | 1 (<1) | NS |

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ACLR, ACL reconstruction; NS, nonsignificant.

Figure 1.

Anterior cruciate ligament revisions included in the current MARS study. There were 1049 primary revisions and 151 multiple revisions. These were divided as depicted in the bar to the right.

Injury Mechanism and Graft Type

The most common mechanism of ACL graft reinjury was a traumatic, noncontact ACL injury (55%) in primary-revision patients compared with a nontraumatic, gradual-onset injury (47%) (P < .01) in multiple-revision patients (Table 1). In the primary-revision group, nontraumatic, gradual-onset injuries occurred less often (25%) compared with the multiple-revision group (47%) (P < .01). There were also differences in nontrau-matic, sudden-onset injuries between groups (P = .04). Patients in the primary-revision group were more likely to have a traumatic, contact injury (13%) than those in the multiple-revision group (7%) (P < .01). Traumatic, noncontact injuries were similarly more common in the primary-revision group (55%) than the multiple-revision group (35%) (P < .001). When controlling for factors including age, BMI, previous meniscal injury, and chondral injury, this difference remained significant (see the Appendix, available online at http://ajsm.sagepub.com/supplemental).

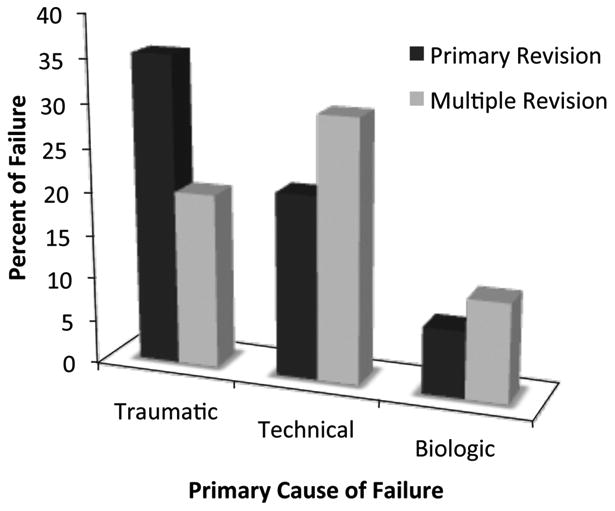

In the primary-revision group, the cause of failure as deemed by the revising surgeon was isolated trauma for 35%, an isolated technical error for 21%, and isolated biological graft failure for 8% of patients. In the multiple-revision group, the mode of failure was deemed as isolated trauma for 20% (P < .01 vs primary revision), isolated technical failure for 29% (P < .01 vs primary revision), and isolated biological graft failure for 11% (P = nonsignificant [NS] vs primary revision) of patients (Figure 2). However, surgeons often deemed the cause of graft failure to be multifactorial. Therefore, in the primary-revision group, the revising surgeon deemed trauma to be a contributing factor to failure 59% of the time and technical error to be a contributing cause 48% of the time. Conversely, in the multiple-revision group, the revising surgeon deemed trauma to be a contributing factor to failure 37% of the time and technical error to be a contributing cause 58% of the time (P = .02 vs primary revision). The prior ACL graft that failed was most often an autograft (74%) in the primary-revision group compared with an allograft (54%) in the multiple-revision group (P < .01).

Figure 2.

Primary cause of failure of anterior cruciate ligament revision reconstructions. There was a higher traumatic failure rate in the single-revision group and a higher technical and biological failure rate in the multiple-revision group.

Meniscal, Cartilage, and Collateral Ligament Injuries

Concomitant knee injuries (meniscal and chondral) were common in all patients (Table 2). A medial meniscal injury was noted in 46% of primary-revision and 41% of multiple-revision patients (P = NS between groups). For primary-revision patients, 63% underwent medial meniscal debridement, and 31% had a medial meniscal repair. For multiple-revision patients, 66% had a medial meniscal debridement, and 23% had repair of their medial meniscal tears.

Table 2. Operative Findingsa.

| Primary-Revision ACLR | Multiple-Revision ACLR | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medial meniscal tears (current) | 481 (46) | 62 (41) | NS |

| Debridement/abradement/trephination | 303 (63) | 41 (66) | NS |

| Transplant | 10 (2) | 3 (5) | NS |

| No treatment | 20 (4) | 4 (6) | NS |

| Repair | 148 (31) | 14 (23) | NS |

| Lateral meniscal tears (current) | 394 (38) | 44 (29) | <.01 |

| Debridement/abradement/trephination | 287 (73) | 26 (59) | .02 |

| Transplant | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | NS |

| No treatment | 50 (13) | 7 (16) | NS |

| Repair | 52 (13) | 11 (25) | .01 |

| Cartilage injury | |||

| Medial femoral condyle | 480 (46) | 88 (58) | <.01 |

| Medial tibial plateau | 142 (14) | 32 (21) | .01 |

| Lateral femoral condyle | 331 (32) | 46 (30) | NS |

| Lateral tibial plateau | 225 (21) | 28 (19) | NS |

| Trochlea | 227 (22) | 41 (27) | .04 |

| Patella | 339 (32) | 59 (39) | .04 |

| Collateral ligament repair/reconstruction | |||

| Medial collateral ligament | 25 (2) | 6 (4) | NS |

| Lateral collateral ligament | 10 (1) | 2 (1) | NS |

Values are expressed as n (%). ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; NS, nonsignificant.

A concurrent lateral meniscal injury was noted in 38% of primary-revision and 29% of multiple-revision patients (P < .01). Treatment of lateral meniscal tears differed significantly between the primary-revision and multiple-revision cohorts. While the majority of lateral meniscal tears were still treated with debridement in the primary-revision (73%) and multiple-revision groups (59%), a significantly larger proportion were repaired (25%) in the multiple-revision group compared with the primary-revision group (13%) (P = .01).

The overall number of meniscal transplants performed at the time of revision ACL reconstruction was low (n = 18). Medial meniscal transplants occurred in 5% of the multiple-revision group compared with 2% in the primary-revision group. Lateral meniscal transplants occurred in 1% of the primary-revision group compared with none in the multiple-revision group. There were no reports of high tibial osteotomies or distal femoral osteotomies.

The most common location of articular cartilage injury in both groups was the medial femoral condyle, patella, and lateral femoral condyle, with at least 30% of all patients having injuries at these locations (Table 2). Chon-droplasty was the most common treatment for cartilage injuries. Surgery on the medial collateral ligament appeared to be more common in the multiple-revision group (4%) than the primary-revision group (2%), but the overall numbers were small and therefore not appropriately powered to detect a statistical difference. Surgery on the lateral collateral ligament was similar between the multiple-revision group (1%) and the primary-revision group (1%).

Tunnel Management

The management of tunnels and use of bone grafts differed significantly between the primary-revision and multiple-revision groups. While approximately half of revision surgeons used a new femoral tunnel aperture, use of the same tunnel (27%) or blended tunnel (19%) was more frequent in the primary-revision group than the multiple-revision group (22% and 14%, respectively; P = NS) (Table 3). Creation of a second tunnel (creating a double-bundle reconstruction) was more common in the multiple-revision group (11%) than the primary-revision group (3%) (P < .01).

Table 3. Technical Characteristics of Revision Surgerya.

| Primary-Revision ACLR | Multiple-Revision ACLR | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral tunnelb | |||

| Same tunnel, optimal position | 286 (27) | 33 (22) | <.01 |

| Same tunnel, compromised position | 21 (2) | 2 (1) | NS |

| New tunnel aperture | 508 (48) | 78 (52) | NS |

| Blended tunnel aperture | 197 (19) | 21 (14) | NS |

| Double tunnel (second tunnel) | 30 (3) | 16 (11) | <.01 |

| Over-the-top | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | |

| Modified over-the-top | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | |

| Femoral tunnel bone grafting | |||

| None performed | 965 (92) | 112 (74) | <.01 |

| Previously staged | 54 (5) | 33 (22) | <.001 |

| Performed at this revision | 26 (3) | 5 (3) | NS |

| Tibial tunnel | |||

| Same tunnel, optimal position | 617 (59) | 73 (48) | <.01 |

| Same tunnel, compromised position | 19 (2) | 4 (3) | NS |

| New tunnel aperture | 173 (17) | 24 (16) | NS |

| Blended tunnel aperture | 213 (20) | 34 (23) | NS |

| Double tunnel (second tunnel) | 26 (3) | 15 (10) | .03 |

| Tibial tunnel bone grafting | |||

| None performed | 964 (92) | 108 (72) | <.01 |

| Previously staged | 56 (5) | 37 (25) | <.001 |

| Performed at this revision | 28 (3) | 5 (3) | NS |

| Graft type | |||

| Autograft | 501 (48) | 92 (61) | <.01 |

| Allograft | 520 (50) | 54 (36) | <.01 |

| Combination autograft and allograft | 27 (3) | 5 (3) | NS |

| Graft source | |||

| Achilles | 35 (3) | 5 (3) | NS |

| Bone–patellar tendon–bone | 557 (53) | 88 (58) | NS |

| Quadriceps | 3 (<1) | 1 (<1) | NS |

| Soft tissue/other | 451 (43) | 57 (38) | NS |

Values are expressed as n (%). ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; NS, nonsignificant.

Statistical analysis was not performed on the over-the-top and modified over-the-top techniques because of insufficient sample size.

Use of the same tibial tunnel (59%) or new tunnel aperture (17%) was more common among primary revisions (P < .01 vs multiple revisions), whereas a blended tunnel aperture (22%) or creation of an entirely new second tunnel (10%) was not statistically different in the multiple-revision group. Bone grafting of dilated femoral tunnels was performed at the time of revision in 3% of primary-revision and 3% of multiple-revision knees (P = NS). It was performed as a staged procedure before revision reconstruction in 5% of primary-revision and 22% of multiple-revision knees (P <.001) (Table 3). Bone grafting of dilated tibial tunnels was performed at the time of revision in 2% of primary-revision and 3% of multiple-revision knees (P = NS). It was performed as a staged procedure before revision reconstruction in 5% of primary-revision and 25% of multiple-revision knees (P < .01) (Table 3).

Graft Source for Revision

Graft source for the current revision ACL reconstruction was 61% autografts and 36% allografts among multiple-revision patients, while primary-revision knees used 48% autografts and 50% allografts (P < .01 between groups). The single most commonly used graft in either group was BPTB (53% for primary revisions, 58% for multiple revisions), followed by soft tissue (43% primary revisions, 38% multiple revisions).

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to utilize a multicen-ter, multisurgeon database to describe the differences between primary-revision and multiple-revision ACL reconstructions, using a large multicenter study to collect data. We found that when compared with patients undergoing a primary-revision procedure, patients undergoing multiple-revision procedures had a lower Marx activity level, a higher rate of atraumatic ACL ruptures, a higher rate of allograft reconstruction, and a higher incidence of medial compartment injuries.

The most interesting difference between the primary-revision group and the multiple-revision group is the mechanism of injury. In the primary-revision group, the most common mechanism of injury was a traumatic incident, but in the multiple-revision group, the most common mechanism was a nontraumatic mechanism. These data suggest that there are fundamental differences in how ACL grafts fail in multiple-revision ACLs. When controlling for meniscal injury as well as other factors, this difference remained significant. Marx activity levels among primary-revision patients were higher than in the multiple-revision patients, so patients in the setting of multiple revisions are failing despite a lower activity level. One possible cause of the difference in the failure rate could be the difference in graft selection. In the first-time revision group, an allograft was a more common graft choice than an autograft (54% vs 25%, respectively) in the previous reconstruction. Previous studies have suggested that an allograft has a higher failure rate in younger patients,13 and the average age of patients in this study was less than 30 years. In the multiple-revision group, surgeons used autografts more often than allografts (61% vs 36%, respectively), suggesting that they thought autografts decrease the risk of recurrent failure. The choice of graft selection is complicated by the fact that an autograft may not be available at the time of a recurrent-revision ACL reconstruction. Based on the available data, it is not clear if autografts in the setting of a multiple-revision knee would change the mechanism of failure, but an improved biological setting may improve outcomes in the multiple-revision knee.

It is often difficult to fully understand the mechanism of failure for patients who have had multiple ACL reconstructions. An important technical error is tunnel malposition, which can cause a higher rate of ACL graft failure.18 In a recent study by Morgan et al,17 60% of primary ACL failures were caused by femoral tunnel malposition. Surgeons judged the femoral tunnel too vertical in 42 cases (35.9%), too anterior in 35 cases (29.9%), and too vertical and anterior in 31 cases (26.5%). In our current study, technical error (most often, tunnel position) was more common in multiple-revision groups, and there was a difference in femoral tunnel management. Surgeons were more likely to use a new femoral tunnel aperture or a double-bundle configuration in a multiple-revision setting to correct for previous femoral malposition. These data suggest that improper tunnel placement places the graft at risk for failure, and it should be corrected at the time of revision to lower the risk of recurrent failure.

The best strategy for the management of tunnel malposition in multiple-revision surgery has not been determined. Management of dilated tunnels with bone grafting occurs approximately 3% of the time when performed at the time of revision ACL surgery. However, previous staged bone grafting occurs 22% of the time in the multiple-revision knee compared with 5% of the time in the primary-revision knee. These data suggest that the bone availability in the tibia and femur is limited after 2 or more ACL reconstructions. This should be communicated to patients before the surgery, as these patients may benefit most from a staged procedure with bone grafting followed by a period of healing.

Concomitant injuries at the time of ACL reconstruction are thought to be important in knee stability, clinical outcomes, and the development of osteoarthritis. The medial meniscus is often found to be torn in the ACL-deficient state.2,6,7,20,22,24 The threshold for the “critical” amount of medial meniscus removed that puts the ACL reconstruction at a higher risk of failure is not known. The medial meniscus has a central role in limiting anterior tibial translation in an ACL-deficient state, and it is thought that medial meniscal deficiency will result in higher ACL graft forces and a higher rate of failure.3 Surprisingly, however, the presence of a medial meniscal injury did not differ between the 2 groups, with 46% of primary-revision patients having a medial meniscal injury and 41% of multiple-revision patients having a medial meniscal injury. Although the rate is not higher between groups, these data can be interpreted to suggest that patients suffering from multiple ACL injuries are incurring further meniscal damage that places the ACL graft at increased risk, which would correlate with biomechanics studies. These data are similar to the findings of Borchers et al,5 who compared primary to revision articular lesions. Both groups had approximately a 40% rate of a new meniscal injury. Thus, in an ACL-deficient state, it appears that the medial meniscus continues to be at risk for further injury. Meniscal transplant was rarely performed in either group but may need to be considered in the future to lower the incidence of recurrent ACL graft failure.

Patients in the multiple-revision group demonstrated a higher incidence of chondral injuries to the medial femoral condyle and medial tibial plateau compared with the primary-revision group. This finding is not surprising given the fact that long-term ACL instability leads to medial compartment joint space narrowing. Borchers et al5 found an increasing incidence of medial femoral con-dyle and tibial plateau injuries when comparing primary ACL reconstruction to revision ACL reconstruction. However, our findings of progressive medial compartment wear, along with the fact that almost half of both the primary and revision ACL groups had medial meniscal injuries, suggest that medial compartment degeneration is an important factor in recurrent ACL graft injury, which may need to be managed more aggressively with cartilage-and meniscus-preserving procedures. There was also a small but significant increase in the rate of chondral injury in the patellofemoral compartment; Brophy et al6 recently found that there was an association between previous meniscal surgery and patellofemoral chondrosis in ACL reconstructions. The authors hypothesized that abnormal meniscal function could result in a degradative biochemical response in the knee, leading to a more diffuse cartilage injury pattern. It may also be that recurrent ACL injury and subsequent knee instability place increased forces on the patellofemoral cartilage, resulting in a higher rate of wear in the patellofemoral joint.

Finally, we found that approximately 60% of revision ACL reconstructions were in men. This is consistent with the current literature, which suggests a higher rate of women with ACL tears but a higher overall number of men with ACL injuries.4 There was no difference in the proportion of men with revision ACL reconstruction regardless of whether it was a primary revision or multiple revision. These results are similar to the proportion of men (57%) undergoing primary ACL reconstruction as reported by the Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON)5,10 and those undergoing revision ACL reconstruction in a recent meta-analysis (66%).22 The high proportion of primary and revision ACL reconstructions among men has not been clearly addressed in the literature. Potential reasons for the high rates of ACL revisions among men may include an increased propensity to return to high-impact sports or incomplete rehabilitation before return to activity. Data from the MOON study indicate that women have a higher rate of tearing the intact contra-lateral ACL, whereas men have a higher rate of rupture of the ACL graft in the first 2 years after ACL reconstruction.21 Further studies investigating the rates of revision ACL surgery compared with the rates of ACL injury among men and women could determine the unique sex-specific factors contributing to revision surgery rates.

This study has several limitations. This is a descriptive study that requires follow-up at 2 years after surgery to assess these factors as predictors for the outcome of multiple-revision ACL reconstruction. Several factors are left to the discretion of the surgeon, including mechanism of failure, technical error, and grading of meniscal and cartilage injuries. Although grading of meniscal and cartilage injuries has been previously validated,9,15 there remains no clear consensus on the proper definition of technical error/proper tunnel position or an ideal method to determine the mechanism of failure. This was minimized as much as possible by the required training of all participating surgeons. In addition, time to failure was not recorded, nor was compliance of the rehabilitation method or the type of rehabilitation protocol utilized. Therefore, individual differences in compliance and adherence to a physical therapy and rehabilitation program cannot be accounted for in this study.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrates important differences in the demographics and intraoperative findings between primary-revision and multiple-revision patients. Our study suggests that despite lower activity levels, patients with multiple-revision ACL reconstructions are at risk for an atraumatic graft failure possibly because of poor tunnel placement, graft selection, and medial compartment lesions. This study gives surgeons relevant data to convey to the patient in regard to expected findings at the time of surgery, which are important to guide expectations of these challenging cases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: The MARS study received funding from the AOSSM, Smith & Nephew (Andover, Massachusetts), National Football League Charities (New York, NY), and Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation (Edison, New Jersey). This project was partially funded by grant No. 5R01-AR060846 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Footnotes

Contributing Authors: John P. Albright, MD; Annunziato (Ned) Amendola, MD; Allen F. Anderson, MD; Jack T. Andrish, MD; Christopher C. Annunziata, MD; Robert A. Arciero, MD; Bernard R. Bach Jr, MD; Champ L. Baker 3rd, MD; Arthur R. Bartolozzi, MD; Keith M. Baumgarten, MD; Jeffery R. Bechler, MD; Jeffrey H. Berg, MD; Geoff Bernas, MD; Stephen F. Brockmeier, MD; Robert H. Brophy, MD; Charles A. Bush-Joseph, MD; J. Brad Butler 5th, MD; John D. Campbell, MD; James L. Carey, MD, MPH; James E. Carpenter, MD; Brian J. Cole, MD; Daniel E. Cooper, MD; Jonathan M. Cooper, DO; Charles L. Cox, MD; R. Alexander Creighton, MD; Diane L. Dahm, MD; Tal S. David, MD; Thomas M. DeBerardino, MD; Warren R. Dunn, MD, MPH; David C. Flanigan, MD; Robert W. Frederick, MD; Theodore J. Ganley, MD; Charles J. Gatt Jr, MD; Steven R. Gecha, MD; James Robert Giffin, MD; Sharon L. Hame, MD; Jo A. Hannafin, MD, PhD; Christopher D. Harner, MD; Norman Lindsay Harris Jr, MD; Keith S. Hechtman, MD; Elliott B. Hershman, MD; Rudolf G. Hoellrich, MD; Timothy M. Hosea, MD; David C. Johnson, MD; Timothy S. Johnson, MD; Morgan H. Jones, MD; Christopher C. Kaeding, MD; Ganesh V. Kamath, MD; Thomas E. Klootwyk, MD; Brett (Brick) A. Lantz, MD; Bruce A. Levy, MD; C. Benjamin Ma, MD; G. Peter Maiers 2nd, MD; Barton Mann, PhD; Robert G. Marx, MD; Matthew J. Matava, MD; Gregory M. Mathien, MD; David R. McAllister, MD; Eric C. McCarty, MD; Robert G. McCormack, MD; Bruce S. Miller, MD, MS; Carl W. Nissen, MD; Daniel F. O'Neill, MD, EdD; MAJ Brett D. Owens, MD; Richard D. Parker, MD; Mark L. Purnell, MD; Arun J. Ramappa, MD; Michael A. Rauh, MD; Arthur C. Rettig, MD; Jon K. Sekiya, MD; Kevin G. Shea, MD; Orrin H. Sherman, MD; James R. Slauterbeck, MD; Matthew V. Smith, MD; Jeffrey T. Spang, MD; Kurt P. Spindler, MD; Michael J. Stuart, MD; LTC Steven J. Svoboda, MD; Timothy N. Taft, MD; COL Joachim J. Tenuta, MD; Edwin M. Tingstad, MD; Armando F. Vidal, MD; Darius G. Viskontas, MD; Richard A. White, MD; James S. Williams Jr, MD; Michelle L. Wolcott, MD; Brian R. Wolf, MD; James J. York, MD.

References

- 1.Ageberg E, Forssblad M, Herbertsson P, Roos EM. Sex differences in patient-reported outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: data from the Swedish knee ligament register. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1334–1342. doi: 10.1177/0363546510361218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn JH, Kim JG, Wang JH, Jung CH, Lim HC. Long-term results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using bone-patellar tendon-bone: an analysis of the factors affecting the development of osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(8):1114–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen CR, Wong EK, Livesay GA, Sakane M, Fu FH, Woo SL. Importance of the medial meniscus in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(1):109–115. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boden BP, Sheehan FT, Torg JS, Hewett TE. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: mechanisms and risk factors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(9):520–527. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201009000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borchers JR, Kaeding CC, Pedroza AD, Huston LJ, Spindler KP, Wright RW. Intra-articular findings in primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a comparison of the MOON and MARS study groups. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1889–1893. doi: 10.1177/0363546511406871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brophy RH, Wright RW, David TS, et al. Association between previous meniscal surgery and the incidence of chondral lesions at revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(4):808–814. doi: 10.1177/0363546512437722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brophy RH, Zeltser D, Wright RW, Flanigan D. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and concomitant articular cartilage injury: incidence and treatment. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(1):112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curl WW, Krome J, Gordon ES, Rushing J, Smith BP, Poehling GG. Cartilage injuries: a review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthros-copy. 1997;13(4):456–460. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn WR, Wolf BR, Amendola A, et al. Multirater agreement of arthroscopic meniscal lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1937–1940. doi: 10.1177/0363546504264586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.In Y, Kwak DS, Moon CW, Han SH, Choi NY. Biomechanical comparison of three techniques for fixation of tibial avulsion fractures of the anterior cruciate ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(8):1470–1478. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, et al. Development and validation of the International Knee Documentation Committee subjective knee form. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):600–613. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290051301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irrgang JJ, Ho H, Harner CD, Fu FH. Use of the International Knee Documentation Committee guidelines to assess outcome following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Trauma-tol Arthrosc. 1998;6(2):107–114. doi: 10.1007/s001670050082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaeding CC, Aros B, Pedroza A, et al. Allograft versus autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: predictors of failure from a MOON prospective longitudinal cohort. Sports Health. 2011;3(1):73–81. doi: 10.1177/1941738110386185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyman S, Koulouvaris P, Sherman S, Do H, Mandl LA, Marx RG. Epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: trends, read-missions, and subsequent knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(10):2321–2328. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marx RG, Connor J, Lyman S, et al. Multirater agreement of arthro-scopic grading of knee articular cartilage. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(11):1654–1657. doi: 10.1177/0363546505275129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marx RG, Stump TJ, Jones EC, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Development and evaluation of an activity rating scale for disorders of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):213–218. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290021601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan JA, Dahm D, Levy B, Stuart MJ. Femoral tunnel malposition in ACL revision reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2012;25(5):361–368. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taggart TF, Kumar A, Bickerstaff DR. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a midterm patient assessment. Knee. 2004;11(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0160(02)00087-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trojani C, Sbihi A, Djian P, et al. Causes for failure of ACL reconstruction and influence of meniscectomies after revision. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(2):196–201. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament revision reconstruction: two-year results from the MOON cohort. J Knee Surg. 2007;20(4):308–311. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, et al. Risk of tearing the intact anterior cruciate ligament in the contralateral knee and rupturing the anterior cruciate ligament graft during the first 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective MOON cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1131–1134. doi: 10.1177/0363546507301318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright RW, Gill CS, Chen L, et al. Outcome of revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(6):531–536. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright RW, Huston LJ, Spindler KP, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of the Multicenter ACL Revision Study (MARS) cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):1979–1986. doi: 10.1177/0363546510378645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu WH, Hackett T, Richmond JC. Effects of meniscal and articular surface status on knee stability, function, and symptoms after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a long-term prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(6):845–850. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300061501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.