Abstract

Purpose of review

To summarize recent studies of hypertension associated with a defect in renal K excretion due to genetic deletions of various components of the large, Ca-activated K channel (BK), and review new evidence and theories regarding K secretory roles of BK in intercalated cells.

Recent Findings

Isolated perfused tubule methods have revealed the importance of BK in flow-induced K secretion. Subsequently, mice with genetically deleted BK subunits revealed the complexities of BK-mediated K secretion. Deletion of the BKα results in extreme aldosteronism, hypertension and an absence of flow-induced K secretion. Deletion of the BKβ1 ancillary subunit results in decreased handling of a K load, increased plasma K, mild aldosteronism and hypertension that is exacerbated by a high K diet. Deletion of the BKβ4 (β4KO) leads to insufficient K handling, high plasma K, fluid retention, but with milder hypertension. Fluid retention in β4KO may be the result of insufficient flow-induced secretion of ATP, which normally inhibits epithelial Na channels (ENaC).

Summary

Classical physiological analysis of electrolyte handling in knock-out mice has enlightened our understanding of the mechanism of handling K loads by renal K channels. Studies have focused on the different roles of the BK-α/β1 and BK-α/β4 in the kidney. BKβ1 hypertension may be a “three-hit” hypertension, involving a K secretory defect, elevated production of aldosterone, and increased vascular tone. The disorders observed in BK knock-out mice have shed new insights on the importance of proper renal K handling for maintaining volume balance and blood pressure.

Keywords: potassium, cortical collecting duct, BK channels, intercalated cells, aldosterone

Introduction

Potassium secretion is regulated in the distal nephron by at least two types of channels: ROMK (Kcnj1; Kir1.1), which is responsible for basal levels of K secretion, and BK. Several laboratories have studied ROMK and its regulation by a variety of signaling pathways [1–4]. Mice respond to aldosterone and a high K diet with increased ROMK expression in luminal membranes of the CCD [5;6]. BKα knock-out mice (BKαKO) exhibit profound aldosteronism but are able to excrete K via compensatory increases in ROMK [7]. However, ROMK knock-outs exhibit normal plasma [K] [8] due to aldosteronism and reduced Na and Cl reabsorption in the thick ascending limb with enhanced distal flow.

BK is normally associated with one of four subunits (BKβ1-β4) and is responsible for flow-induced K secretion [9–13]. Other tissues that actively secrete K, such as the submandibular gland [14], pancreas [15] and distal colon [16;17], seem to rely only on BK. Although BK was the first K-selective channels described in the distal nephron [18], its role in K secretion has been elucidated more recently as reported in other reviews of this topic [19–24]. Other renal K channels, besides ROMK and BK, may secrete K [25;26]; however, their roles are not yet defined.

It has been known for several years that flow enhances K secretion [27–30]. The relevance of flow-induced K secretion relates to consuming a high K diet, which elevates plasma [K] and stimulates the production of aldosterone, which enhances the driving force for K secretion. Potassium secretion continues until the transtubular electrochemical gradient reverses and favors K reabsorption [31]. At this point, the [K] increases in the medullary interstitium to levels that inhibit Na and Cl transport in the thick ascending limb [32], thereby increasing flow like a natural loop diuretic. The increased tubular volume [33] maintains a low tubular [K] so that K secretion remains robust. In this process, at least two forms of BK are involved – BKα with the BKβ1 (BK-α/β1) and BKβ4 (BK-α/β4).

Localization of BK components

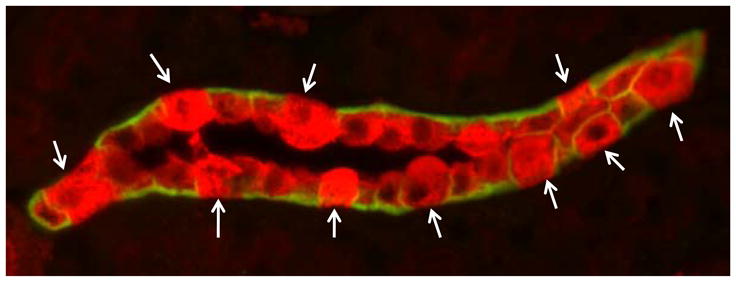

Several years ago, patch cIamp analysis revealed the presence of BK in isolated, split-open, cortical collecting ducts of rabbits [18]. More recently, investigators revealed that iberiotoxin, a specific blocker of BK, inhibited flow-induced K secretion in either the micropunctured late distal tubule (connecting tubule; CNT) [34] or isolated perfused CCD [11]. Improved microscopy revealed that single BK currents were present in Na and K transporting principal cells (PC) but the majority of BK were in acid-base transporting intercalated cells (IC) [35]. Using immunohistochemical analysis, we subsequently showed that the BKβ1 was expressed in the apical membrane of the mouse CNT and in the initial collecting ducts of the rabbit [9], whereas BKβ4 was present with BKα in IC [36]. As shown in figure 1, immunohistochemical analysis of a connecting tubule confirmed that BKα is more densely expressed in IC, anti-AQP3 negative cells. BK-α is less densely expressed in CNT cells, where BKβ1 resides. Importantly, we determined that BKβ4 was present in all IC, whether these were IC-α, IC-β, or nonα/β-IC.

Figure 1.

Double immunohistochemical staining of renal section, highlighting a connecting tubule from a WT mouse on a normal diet, revealed predominant BK-α (red) on intercalated cells (IC), marked by absence of anti-AQP3 (green), which highlights the basolateral membrane of CNT cells. Arrows indicate IC.

RT-PCR [37] and Western analysis [36] has identified BKβ2 and BKβ3 in the distal nephron, but their specific roles in K secretion have not been investigated. That BKαKO, β1KO, and β4KO mice all have profound imbalances in electrolyte and volume management [7;33;38] is good reason to examine the K secretory roles of BK-α/β1 and BK-α/β4 in the CNT and IC.

BK-α/β1, K secretion, and hypertension

Volume expanded mice with genetic deletion of only the BKβ1 subunit (β1KO) excrete substantially less K than wild type (WT) mice, indicating that BK-α/β1 in CNT cells secretes K in response to flow [39]. These studies were performed when β1KO were anesthetized and the animals were perfused with physiological saline that included 5 mM K. However, the normal plasma [K] of mice on a normal diet is 4.1 mM [38]. An increase in plasma [K] from 4 to 5 mM can cause aldosterone-independent K secretion and a fairly large increase in aldosterone production [38;40;41], which can cause non-genomic increases in K secretion. A micropuncture study of ROMK knock-out mice confirmed that K secretion in the CNT occurs via an iberiotoxin-sensitive (BK) channel [34]. However, because flow and plasma K were both increased in that study, the independent roles of aldosterone, high plasma K and flow, on the activation of BK-α/β1 are still not understood.

We further investigated the role of BK-α/β1 in electrolyte and volume balance utilizing β1KO on diets with varying quantities of K. When WT and β1KO were fed a high K diet (5%K, 0.3% Na) the urinary flows of both increased by 4.5-fold, consistent with its loop inhibiting effect; however, β1KO excreted 20% less K than WT.

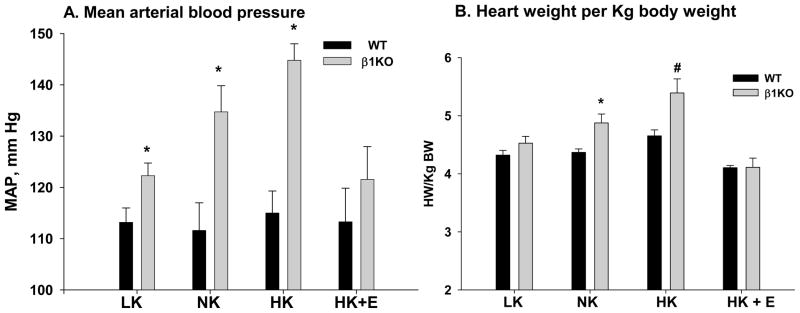

A significant change in volume balance and blood pressure best illustrates the relevance of the β1KO defect in K secretion. Catheterization measurements determined that β1KO were hypertensive by 20 mmHg (mean arterial pressure: MAP) and the heart size was significantly increased, compared to WT, on a normal diet [42]. We repeated these studies measuring blood pressure with the tail cuff method and found that β1KO had a MAP of 21 mmHg above WT [38]. The hypertension of β1KO was exacerbated when mice were placed on a high K diet and mitigated when fed a low K diet (figure 2A). The failure of high K fed β1KO to secrete K at a substantial rate led to increased plasma [K], which stimulated aldosterone production with ensuing Na and fluid retention. Removing the fluid with eplerenone, an aldosterone receptor blocker, reduced the MAP toward values observed in mice on a low K diet. Therefore, the hypertension of β1KO was mostly the result of fluid retention.

Figure 2.

Illustration of significance of findings with respect to hypertension. A. The hypertension of β1KO is exacerbated by a high K diet (HK) and alleviated with a low K diet (LK) or eplerenone (HK+E), demonstrating defective K handling and aldosteronism as the cause of hypertension [38]. B. Illustration of cardiac hypertrophy, measured by heart wt per pre-diet Kg body weight, in β1KO. Cardiac hypertrophy is exacerbated in β1KO on only ten days of HK diet and prevented by addition of eplerenone, which prevents fluid accumulation. *P<0.05 compared with WT using the t-test for unpaired data. #P<0.02 compared with all groups using ANOVA plus Student-Newman-Keuls.

As shown in figure 2B, the high K induced hypertension observed in β1KO was reflected by increased heart weight (HW) per pre-diet body weight (BW). When the two groups were compared, we found a significantly elevated HW/BW in β1KO, compared to WT, on a normal diet, as shown previously by Brenner et al [42]. When the multiple groups were compared, we found that the HW/BW of β1KO was further increased when mice consumed a high K diet and reduced to values not different from those of WT when treated with either a low K diet or adding eplerenone with the high K diet.

The eplerenone experiments showed that fluid retention has a major role in the elevated MAP of β1KO; however, sympathetic tone has a synergistic effect with fluid retention. In anesthetized mice, catheterization determined that MAP of β1KO was only 11 mmHg greater than WT. MAP values for β1KO were greater in awake, compared with anesthetized mice, indicating that sympathetic stimulation contributes to the hypertension. Nevertheless, in the absence of fluid retention, the hypertension of β1KO is very mild, with an MAP of only 7 mmHg above control, a small value compared with 33 mmHg above control in β1KO on a high K diet. This could explain why diuretic therapy is the most effective treatment for hypertension and why the only discovered monogenic forms of hypertension have been of the renal-adrenal axis [43].

To date, BKβ1 polymorphisms have not been linked to hypertension; however several studies have revealed significant protection from hypertension in the gain-in-function BKβ1 Glu65Lys mutant, which enhances the Ca sensitivity of BK when associating with the BKα [44–46]. It will be interesting to determine whether an enhanced ability to excrete a K load and the prevention of Na and fluid retention are hallmarks of this resistance to hypertension.

It was also interesting that β1KO placed on a low Na diet were unable to retain Na and fluid as WT, leading to severe hyponatremia and hemoconcentration [47]. The mechanism involved was not determined; however, the appearance of the BK-α/β1 in the basolateral membrane of WT on a Na deficient diet indicated that the BK-α/β1 has a role to enhance Na reabsorption in the CCD when Na delivery is very low. Moreover, Na deficient β1KO were still slightly hypertensive, by approximately 7 mm Hg [21], compared to Na-deficient WT. It is possible that a pressure natriuresis results in the inordinate loss of Na in the Na-deficient β1KO.

Role of BK-α/β4 in IC in flow-induced K secretion

We were surprised at the predominant localization of BK-α/β4 in IC. IC are plastic cells with a variety of phenotypes - the acid-secreting IC-α and base-secreting IC-β- are readily identifiable by immuno-identification of H-ATPase on the apical or basolateral membranes, respectively. However, IC-non-α/non-β, primarily in the CCD, have a more ambiguous phenotype with predominant cytoplasmic staining for H-ATPase. IC-non-α/non-β can transform to IC-α or IC-β depending on the acid/base status of the organism [48]. The IC-α and IC-β have different Cl concentrations of approximately 45 mM and 10 mM [49], and basolateral membrane potentials of −35 mV and −60 mV, respectively, [50]. Because IC-α and IC-β have such diverse properties, it would not be surprising if BK-α/β4 has different physiological roles in these cells.

Studies of isolated CCDs perfused with high flows demonstrate that the BK channels in IC must be playing a role in flow-mediated K secretion [11]. However, the IC contains a very low level of Na-K-ATPase compared with PC [33;51–53]. Unlike PC, the quantity of Na-K-ATPase in IC does not increase with a high K diet [33]. In the absence of a source of substantial K delivery, and because the BK channel is closed at resting potentials, it was originally considered a volume regulatory channel in renal cells [54]. This was difficult to assess directly without a cell culture model of IC that expressed BK that could be studied at the single channel level.

MDCK-C11 cells (C11) are specific IC clones with many IC properties [55;56]. Like all cultured cells, C11 do not replicate entirely the known properties of IC; however, BK-α/β4 are expressed in C11 apical membranes [57]. We determined that C11 exhibit BK-α/β4 dependent volume reduction in response to high shear stress [57]. This phenomenon was also investigated in vivo. Normally, IC are larger than PC and protrude into the lumens of CNTs and CCDs from WT mice on a control diet. However, when WT are fed a high K diet, the increased urinary flow is accompanied by a reduction in IC size. Flow in high K fed β4KO was reduced by 30% with little reduction in IC size. These results indicated that the reduction in IC size also reduces tubular resistance and enhances luminal flow. The enhanced flow was estimated to increase the chemical gradient for K secretion by 30%.

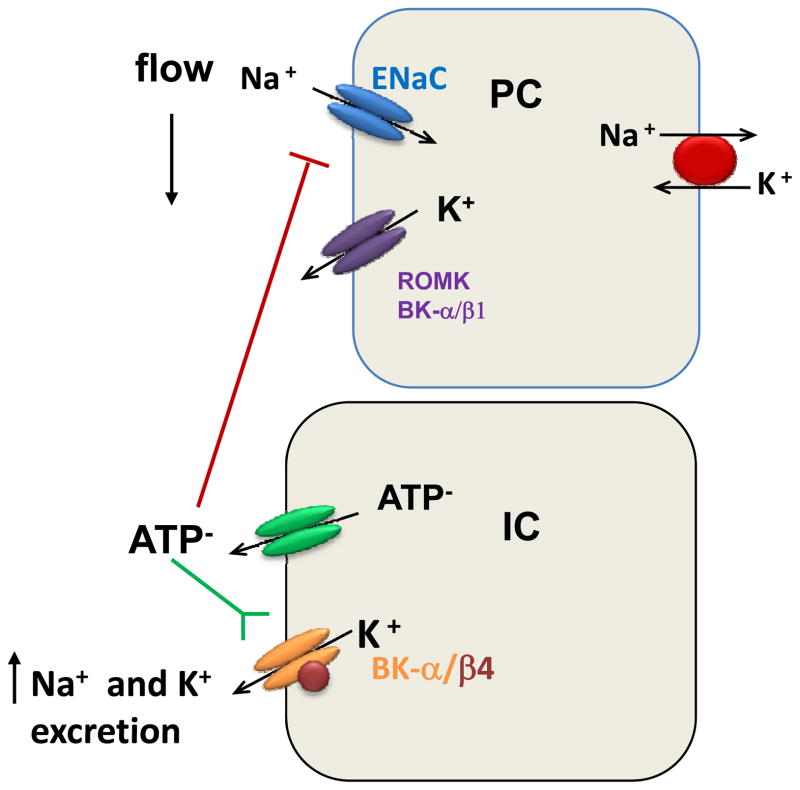

β4KO also retain fluid [33] and are slightly hypertensive [21]. The fluid retention, but not the hypertension, is exacerbated by high dietary K. When fed a high K diet, β4KO also exhibit slight hyperkalemia and aldosteronism, but this may not explain their considerable Na and volume retention. A recent study suggested that an inability of IC from β4KO to secrete ATP may have a role in the Na retention [58]. Luminal ATP inhibits ENaC-mediated Na reabsorption in the CCD [59;60]. ATP is secreted from intercalated cells, as well as other cells [61–64], in response to high fluid flow. In MDCK-C11, secreted ATP serves as a counter-anion to the K secreted via apical BK-α/β4, as indicated by the reduced ATP secretion when applying BKβ4 siRNA. Moreover, high K fed β4KO exhibit a reduction in urinary ATP. As shown in figure 3, with high dietary K, the high flow is meant to stimulate the ratio of K secreted to Na reabsorbed. Reduced ATP secretion in response to flow can partially explain why β4KO exhibit enhanced Na reabsorption and fluid retention.

Figure 3.

Illustration of role of ATP in collecting ducts on Na and K transport. High flow induced by a high K diet initiates the release of ATP, a counter anion with the K loss in IC. ATP inhibits ENaC-mediated Na reabsorption and activates BK-α/β4 causing an increase in the ratio of K excreted to Na reabsorbed.

Future directions

The future of regulation of BK may relate to the WNK (With No Lysine) kinases, shown to distinguish between high aldosterone intended to enhance K secretion vs. high aldosterone intended to enhance Na reabsorption. WNKs, which phosphorylate SPAK, regulate NKCC, NCC, KCC, ENaC and ROMK [65–69]. However, more recent studies have implicated WNKs in the regulation of renal BK channels [70;71]. It will be interesting to determine the role of WNKs in Na-independent K secretion, when Na reabsorption is very low and the demand for K secretion is very high.

Conclusions

BK channels are localized in the CNT as BK-α/β1 in CNT cells and are localized in all IC cells of the CNT and CCD as BK-α/β4. On a regular diet, β1KO are hypertensive by four different studies and the heart size is significantly increased compared with WT controls. When fed a high K diet for only ten days, flow is increased by over four-fold in mice in order to maintain low luminal [K] and maintain a concentration gradient for K secretion. β1KO accumulate fluid, are more hypertensive and heart size is greater when compared with WT. BK-α/β4 in IC are activated by high flow-induced shear stress, with ensuing loss of intracellular K content and cell shrinkage, causing an increased luminal diameter and reduced resistance to flow. High flow induces negatively charged ATP secretion, coupled with K extrusion from IC. ATP extrusion in the distal tubule lumens enhances the ratio of K secretion to Na reabsorption by inhibiting ENaC-mediated Na reabsorption and activating BK-α/β4-mediated K secretion.

Key points.

The physiological role of BK in the distal nephron is defined by its β-subunit.

The BK plays a pivotal role in renal K handling for maintaining volume balance and blood pressure.

Intercalated cells may have a larger role in Na/K balance than previous thought.

Acknowledgments

Support: This project was funding by National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants RO1 DK49461 and RO1 DK73070 (to SCS) and American Heart Association-Heartland Affiliate fellowship #0610059Z (to PRG).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest involved in this manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Liou HH, Zhou SS, Huang CL. Regulation of ROMK1 channel by protein kinase A via a phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5820–5825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray DA, Frindt G, Palmer LG. Quantification of K+ secretion through apical low-conductance K channels in the CCD. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F117–F126. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00471.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W. Regulation of the ROMK channel: interaction of the ROMK with associate proteins. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F826–F831. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.6.F826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sansom SC, Welling PA. Two channels for one job. Kidney Int. 2007;72:529–530. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frindt G, Shah A, Edvinsson JM, Palmer LG. Dietary K regulates ROMK channels in connecting tubule and cortical collecting duct of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90527.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wald H, Garty H, Palmer LG, Popovtzer MM. Differential regulation of ROMK expression in kidney cortex and medulla by aldosterone and potassium. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:F239–F245. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.2.F239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieg T, Vallon V, Sausbier M, Sausbier U, Kaissling B, Ruth P, Osswald H. The role of the BK channel in potassium homeostasis and flow-induced renal potassium excretion. Kidney Int. 2007;72:566–573. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu M, Wang T, Yan Q, Yang X, Dong K, Knepper MA, Wang W, Giebisch G, Shull GE, Hebert SC. Absence of small conductance K+ channel (SK) activity in apical membranes of thick ascending limb and cortical collecting duct in ROMK (Bartter’s) knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37881–37887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206644200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pluznick JL, Wei P, Grimm PR, Sansom SC. BK-{beta}1 subunit: immunolocalization in the mammalian connecting tubule and its role in the kaliuretic response to volume expansion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F846–F854. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00340.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taniguchi J, Imai M. Flow-dependent activation of maxi K+ channels in apical membrane of rabbit connecting tubule. J Membr Biol. 1998;164:35–45. doi: 10.1007/s002329900391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu W, Morimoto T, Woda C, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Ca2+ dependence of flow-stimulated K secretion in the mammalian cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F227–F235. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00057.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woda CB, Bragin A, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Flow-dependent K+ secretion in the cortical collecting duct is mediated by a maxi-K channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F786–F793. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.5.F786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woda CB, Miyawaki N, Ramalakshmi S, Ramkumar M, Rojas R, Zavilowitz B, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Ontogeny of flow-stimulated potassium secretion in rabbit cortical collecting duct: functional and molecular aspects. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F629–F639. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00191.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romanenko VG, Nakamoto T, Srivastava A, Begenisich T, Melvin JE. Regulation of membrane potential and fluid secretion by Ca2+-activated K+ channels in mouse submandibular glands. J Physiol. 2007;581:801–817. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15*.Venglovecz V, Hegyi P, Rakonczay Z, Jr, Tiszlavicz L, Nardi A, Grunnet M, Gray MA. Pathophysiological relevance of apical large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels in pancreatic duct epithelial cells. Gut. 2010 doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.214213. This article demonstrated by patch-clamp analysis that BK channels play a critical role in regulating bicarbonate secretion in isolated guinea pig pancreatic ducts. Activation of the BK channel increased HCO3- secretion while inhibiting BK channels decreased HCO3- secretion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sausbier M, Matos JE, Sausbier U, Beranek G, Arntz C, Neuhuber W, Ruth P, Leipziger J. Distal colonic K(+) secretion occurs via BK channels. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1275–1282. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorensen MV, Matos JE, Sausbier M, Sausbier U, Ruth P, Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. Aldosterone increases KCa1.1 (BK)-channel-mediated colonic K+ secretion. J Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter M, Lopes AG, Boulpaep EL, Giebisch GH. Single channel recordings of calcium-activated potassium channels in the apical membrane of rabbit cortical collecting tubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4237–4239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pluznick JL, Sansom SC. BK channels in the kidney: role in K(+) secretion and localization of molecular components. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F517–F529. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00118.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimm PR, Sansom SC. BK channels in the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16:430–436. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32826fbc7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimm PR, Sansom SC. BK channels and a new form of hypertension. Kidney Int. 2010;78:956–962. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu RS, Marx SO. The BK potassium channel in the vascular smooth muscle and kidney: alpha- and beta-subunits. Kidney Int. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodan AR, Huang CL. Distal potassium handling based on flow modulation of maxi-K channel activity. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18:350–355. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32832c75d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wildman SS, Kang ES, King BF. ENaC, renal sodium excretion and extracellular ATP. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5:481–489. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Carrisoza-Gaytan R, Salvador C, Satlin LM, Liu W, Zavilowitz B, Bobadilla NA, Trujillo J, Escobar LI. Potassium secretion by voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F255–F264. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00697.2009. This article presents evidence that Kv1.3 channels exhibit increased apical membrane localization in intercalated cells of rat CCDs on a high K (10% wt/wt) diet and may participate in K secretion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy DI, Wanderling S, Biemesderfer D, Goldstein SA. MiRP3 acts as an accessory subunit with the BK potassium channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F380–F387. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00598.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright FS. Flow-dependent transport processes: filtration, absorption, secretion. Am J Physiol. 1982;243:F1–11. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1982.243.1.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reineck HJ, Osgood RW, Ferris TF, Stein JH. Potassium transport in the distal tubule and collecting duct of the rat. Am J Physiol. 1975;229:1403–1409. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.229.5.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khuri RN, Strieder WN, Giebisch G. Effects of flow rate and potassium intake on distal tubular potassium transfer. Am J Physiol. 1975;228:1249–1261. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.228.4.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunau RT, Jr, Webb HL, Borman SC. Characteristics of the relationship between the flow rate of tubular fluid and potassium transport in the distal tubule of the rat. J Clin Invest. 1974;54:1488–1495. doi: 10.1172/JCI107897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of rat cortical collecting duct: determinants of the transtubular potassium gradient. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F1072–F1092. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.6.F1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stokes JB. Consequences of potassium recycling in the renal medulla. Effects of ion transport by the medullary thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:219–229. doi: 10.1172/JCI110609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33**.Holtzclaw JD, Grimm PR, Sansom SC. Intercalated cell BK-alpha/beta4 channels modulate sodium and potassium handling during potassium adaptation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:634–645. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009080817. This article demonstrated that β4-KO mice on a high (5%) K diet had decreased urinary flow, fractional secretion of both K and Na, higher plasma K, and more fluid retention than wild type mice on the same diet. This article indicates that BK-β4, expressed in intercalated cells in the distal nephron, plays a role in K secretion in response to high K diet. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bailey MA, Cantone A, Yan Q, MacGregor GG, Leng Q, Amorim JB, Wang T, Hebert SC, Giebisch G, Malnic G. Maxi-K channels contribute to urinary potassium excretion in the ROMK-deficient mouse model of Type II Bartter’s syndrome and in adaptation to a high-K diet. Kidney Int. 2006;70:51–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pacha J, Frindt G, Sackin H, Palmer LG. Apical maxi K channels in intercalated cells of CCT. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:F696–F705. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.4.F696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimm PR, Foutz RM, Brenner R, Sansom SC. Identification and localization of BK-beta subunits in the distal nephron of the mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F350–F359. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00018.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Najjar F, Zhou H, Morimoto T, Bruns JB, Li HS, Liu W, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Dietary K+ regulates apical membrane expression of maxi-K channels in rabbit cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F922–F932. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00057.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38**.Grimm PR, Irsik DL, Settles DC, Holtzclaw JD, Sansom SC. Hypertension of Kcnmb1−/− is linked to deficient K secretion and aldosteronism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11800–11805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904635106. This study demonstrated that β1-KO mice are hypertensive, volume expanded, and have decreased urinary K and Na clearances compared to wild type mice. These conditions are exacerbated when feed a high K (5%) diet, but not when feed a high K diet and given eplerenone. This study demonstrated that the majority of hypertension in β1-KO mice is due to fluid retention and aldosteronism. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pluznick JL, Wei P, Carmines PK, Sansom SC. Renal fluid and electrolyte handling in BKCa-beta1−/− mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F1274–F1279. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00010.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spat A. Glomerulosa cell--a unique sensor of extracellular K+ concentration. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;217:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dluhy RG, Axelrod L, Underwood RH, Williams GH. Studies of the control of plasma aldosterone concentration in normal man. II. Effect of dietary potassium and acute potassium infusion. J Clin Invest. 1972;51:1950–1957. doi: 10.1172/JCI107001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 2000;407:870–876. doi: 10.1038/35038011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell. 2001;104:545–556. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelley-Hedgepeth A, Peter I, Kip K, Montefusco M, Kogan S, Cox D, Ordovas J, Levy D, Reis S, Mendelsohn M, Housman D, Huggins G. The protective effect of KCNMB1 E65K against hypertension is restricted to blood pressure treatment with beta-blockade. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22:512–515. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez-Fernandez JM, Tomas M, Vazquez E, Orio P, Latorre R, Senti M, Marrugat J, Valverde MA. Gain-of-function mutation in the KCNMB1 potassium channel subunit is associated with low prevalence of diastolic hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1032–1039. doi: 10.1172/JCI20347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senti M, Fernandez-Fernandez JM, Tomas M, Vazquez E, Elosua R, Marrugat J, Valverde MA. Protective effect of the KCNMB1 E65K genetic polymorphism against diastolic hypertension in aging women and its relevance to cardiovascular risk. Circ Res. 2005;97:1360–1365. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196557.93717.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimm PR, Irsik DL, Liu L, Holtzclaw JD, Sansom SC. Role of BKbeta1 in Na+ reabsorption by cortical collecting ducts of Na+-deprived mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F420–F428. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00191.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Awqati Q. Plasticity in epithelial polarity of renal intercalated cells: targeting of the H(+)-ATPase and band 3. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C1571–C1580. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.6.C1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boettger T, Hubner CA, Maier H, Rust MB, Beck FX, Jentsch TJ. Deafness and renal tubular acidosis in mice lacking the K-Cl co-transporter Kcc4. Nature. 2002;416:874–878. doi: 10.1038/416874a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muto S, Giebisch G, Sansom S. Effects of adrenalectomy on CCD: evidence for differential response of two cell types. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:F742–F752. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.253.4.F742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beck FX, Dorge A, Blumner E, Giebisch G, Thurau K. Cell rubidium uptake: a method for studying functional heterogeneity in the nephron. Kidney Int. 1988;33:642–651. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sabolic I, Herak-Kramberger CM, Breton S, Brown D. Na/K-ATPase in intercalated cells along the rat nephron revealed by antigen retrieval. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:913–922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V105913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sauer M, Dorge A, Thurau K, Beck FX. Effect of ouabain on electrolyte concentrations in principal and intercalated cells of the isolated perfused cortical collecting duct. Pflugers Arch. 1989;413:651–655. doi: 10.1007/BF00581816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guggino SE, Guggino WB, Green N, Sacktor B. Ca2+-activated K+ channels in cultured medullary thick ascending limb cells. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:C121–C127. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.252.2.C121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gekle M, Wunsch S, Oberleithner H, Silbernagl S. Characterization of two MDCK-cell subtypes as a model system to study principal cell and intercalated cell properties. Pflugers Arch. 1994;428:157–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00374853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tararthuch AL, Fernandez R, Malnic G. Cl- and regulation of pH by MDCK-C11 cells. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40:687–696. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2007000500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57*.Holtzclaw JD, Liu L, Grimm PR, Sansom SC. Shear stress-induced volume decrease in C11-MDCK cells by BK-{alpha}/{beta}4. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F507–F516. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00222.2010. This study showed that BK-α/β4 plays a role in shear-induced K loss from intercalated cells, and that BK-α/β4 regulates intercalated cell volume during high flow conditions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58**.Holtzclaw JD, Cornelius RB, Hatcher LI, Sansom SC. Coupled ATP and potassium efflux from intercalated cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00112.2011. This study revealed that flow-mediated ATP secretion from intercalated cells was linked to activation of BK-a/b4. Because luminal ATP inhibits ENaC-mediated Na reabsorption, a deficiency of ATP secretion from intercalated cells of beta4-KO mice can explain their Na and volume retention. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pochynyuk O, Bugaj V, Vandewalle A, Stockand JD. Purinergic control of apical plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 levels sets ENaC activity in principal cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F38–F46. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00403.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pochynyuk O, Bugaj V, Rieg T, Insel PA, Mironova E, Vallon V, Stockand JD. Paracrine regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel in the mammalian collecting duct by purinergic P2Y2 receptor tone. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36599–36607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807129200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riddle RC, Taylor AF, Rogers JR, Donahue HJ. ATP release mediates fluid flow-induced proliferation of human bone marrow stromal cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:589–600. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guyot A, Hanrahan JW. ATP release from human airway epithelial cells studied using a capillary cell culture system. J Physiol. 2002;545:199–206. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bodin P, Bailey D, Burnstock G. Increased flow-induced ATP release from isolated vascular endothelial cells but not smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1203–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Woo K, Dutta AK, Patel V, Kresge C, Feranchak AP. Fluid flow induces mechanosensitive ATP release, calcium signalling and Cl- transport in biliary epithelial cells through a PKCzeta-dependent pathway. J Physiol. 2008;586:2779–2798. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kahle KT, Wilson FH, Leng Q, Lalioti MD, O’Connell AD, Dong K, Rapson AK, MacGregor GG, Giebisch G, Hebert SC, Lifton RP. WNK4 regulates the balance between renal NaCl reabsorption and K+ secretion. Nat Genet. 2003;35:372–376. doi: 10.1038/ng1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ring AM, Cheng SX, Leng Q, Kahle KT, Rinehart J, Lalioti MD, Volkman HM, Wilson FH, Hebert SC, Lifton RP. WNK4 regulates activity of the epithelial Na+ channel in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4020–4024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611727104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wade JB, Fang L, Liu J, Li D, Yang CL, Subramanya AR, Maouyo D, Mason A, Ellison DH, Welling PA. WNK1 kinase isoform switch regulates renal potassium excretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8558–8563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603109103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Subramanya AR, Yang CL, McCormick JA, Ellison DH. WNK kinases regulate sodium chloride and potassium transport by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron. Kidney Int. 2006;70:630–634. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garzon-Muvdi T, Pacheco-Alvarez D, Gagnon KB, Vazquez N, Ponce-Coria J, Moreno E, Delpire E, Gamba G. WNK4 kinase is a negative regulator of K+-Cl- cotransporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1197–F1207. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00335.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang SS, Lo YF, Yu IS, Lin SW, Chang TH, Hsu YJ, Chao TK, Sytwu HK, Uchida S, Sasaki S, Lin SH. Generation and analysis of the thiazide-sensitive Na(+)-Cl(−) cotransporter (Ncc/Slc12a3) Ser707X knockin mouse as a model of Gitelman syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2010 doi: 10.1002/humu.21364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang SS, Morimoto T, Rai T, Chiga M, Sohara E, Ohno M, Uchida K, Lin SH, Moriguchi T, Shibuya H, Kondo Y, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Molecular pathogenesis of pseudohypoaldosteronism type II: generation and analysis of a Wnk4(D561A/+) knockin mouse model. Cell Metab. 2007;5:331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]