Abstract

Background

Stroke survivors often have impairments that make it difficult for them to function safely in their home environment.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to identify occupational performance barriers in the home and describe the subsequent recommendations offered to stroke survivors and their caregivers.

Methods

An occupational therapist administered a home safety tool to assess stroke survivors' home environments, determine home safety problems, and provide recommendations.

Findings

Among 76 stroke survivors, the greatest problems were indentified in the categories of bathroom, mobility, and communication. Two case studies illustrate the use of the home safety tool with this population.

Implications

The home safety tool is helpful in determining the safety needs of stroke survivors living at home. We recommend the use of the home safety tool for occupational therapists assessing the safety of the home environment.

Keywords: stroke, recovery, home safety evaluation, activities of daily living

Introduction

Stroke, a primary cause of long term disability, affecting as many as 6.4 million people in the United States (American Heart Association, 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010) is the result of an occlusion in or bursting of a blood vessel in the brain. Stroke occurs suddenly, damaging localized portions of the brain and resulting in a wide range of impairments including language, motor, visual perceptual, sensory, and cognitive deficits (Pulaski, 2003). A stroke may cause severe limitations of mobility and cognition, causing difficulties in performing activities of daily living (ADL). A survey by the National Stroke Association reported that 87% of long term stroke survivors had ongoing motor problems, 54% had difficulty walking, 52% had difficulty with hand movements and 58% had spasticity (Jones, 2006). Even a mild stroke may result in limitations in leisure activities and other meaningful life roles (Clark & Smith, 1999; Gillen, 2006; Hafsteinsdottir & Grypdonck, 1997). A national study of Canadian seniors with strokes reported that functional disabilities in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (i.e., cooking, shopping, or laundry) were correlated with a decreased feeling of control and mastery, and reduced participation in social activities (Clarke, Marshall, Black, & Colantonio, 2002). Decreases in ability to function are related to excess stress and depression among stroke survivors and their caregivers (Ostwald, Bernal, Cron, & Godwin, 2009).

Most stroke survivors return home to an environment that poses many challenges. Occupational therapy is often prescribed for stroke survivors, in hopes of improving the transition from hospital to home. Home safety becomes one of the many issues faced by stroke survivors and their families. While the safety of the interior of the home is a primary concern for stroke survivors due to their physical and cognitive limitations, people living with stroke also report problems with the external environment of their home such as steep wheelchair ramps. The interaction between these limitations and the environment can affect the person's access to and participation in ADL, IADL, and leisure activities (Reid, 2004). Often the home environment must be modified in order to allow for optimum functioning for the individual (Reid, 2004; Rowles, 1987). Home modifications can include installing ramps on the outside of the home, removing rugs, rearranging furniture and even arranging the bottom floor of a two-story house to be the main location of residence.

Falls are a major concern for all older people, but stroke survivors who live at home have more than twice the of risk of falling as community dwelling people who have not experienced a stroke (Jorgensen, Engstad, & Jacobsen, 2002). Kelley et al. (2010) reported that 66% of the stroke survivors who completed the intervention in the study known as Committed to Assisting with Recovery After Stroke (CAReS) fell a minimum of one time over the course of one year. Various explanations have been offered for the increased rate of falls after stroke. Jorgensen et al. (2002) found that depression was a major predictor of falls, while Nonnekes et al. (2010) reported that a deficit in the stroke survivor's ability to visually trigger step adjustments increased the likelihood of falling.

This is the first paper reporting the use of the home safety assessment known as the Safety Assessment of Function and the Environment for Rehabilitation (SAFER) Tool (Chiu, Oliver, Marshall, & Letts, 2001) solely with a population of stroke survivors. Although the SAFER Tool manual reports that the assessment has been used with persons who have had a stroke (Chiu et al., 2001, p. 5), no literature reporting its use specifically with stroke survivors was found by searching the following search engines and databases: Academic Search Complete, American Journal of Occupational Therapy Online, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy via Health Reference Center Academic, CINAHL, E-Medicine, Emerald, Google, Google Scholar, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, Journals@Ovid, MEDLINE (EBSCO version), OT Search, PsycArticles, PsycINFO, PubMed, Science Direct, Social Work Abstracts, Web of Science and Wiley Online Library, as well as a hand search of the reference lists of pertinent articles obtained.

The purpose of this article is to identify barriers encountered by stroke survivors in the performance of their basic and instrumental activities of daily living (BADL and IADL) and describe the recommendations made to the stroke survivors by occupational therapy. A second objective is to describe the utility and therapeutic benefit of the SAFER Tool (Chiu et al., 2001) for home safety assessment. This home safety intervention was part of a funded interdisciplinary randomized controlled trial known as CAReS that enrolled 159 stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers over a 5-year period.

Methods

Design

This study used a descriptive design to synthesize the evaluation results from 76 participants who were administered the SAFER Tool (Chiu et al., 2001). The findings include a non-parametric analysis of stroke survivor demographic characteristics with SAFER Tool scores. Descriptive statistics are used to describe the characteristics of a population (Portney & Watkins, 2009, p. 385).

Parent study

CAReS was a randomized controlled trial, funded for 5 years. Stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers (n=159 dyads) were recruited from 5 rehabilitation sites immediately prior to discharge and followed for 12 months (Schulz, Wasserman & Ostwald, 2006). Dyads were randomly assigned to a home-based interdisciplinary intervention delivered by advanced practice nurses, occupational therapists and physical therapists for 6 months using 39 specific protocols (Ostwald, Davis, Hersch, Kelley, & Godwin, 2008) or a mail-based educational intervention group. Quantitative data, including FIM™ and GDS-15 scores, and qualitative data were collected at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months from all stroke survivors and spousal caregivers. Institutional Review Board approval for the CAReS study was obtained from the IRBs of the 5 hospital systems where stroke survivors were recruited, as well as the two universities involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to participation.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for stroke survivors participating in the CAReS study required the following: at least 50 years of age; English-speaking; experienced a stroke in the past 12 months; planning to be discharged to home with their spouse/significant other; and living within 50 miles of the hospital/university area. Exclusion criteria included having a spouse or significant other who was unwilling or unable to participate, being on hospice care, and having disorders such as dementia or global aphasia which prevented them from participation in education provided by the study (Ostwald, Davis, et al., 2008).

Data Collection

The SAFER Tool (Chiu et al., 2001) was administered by the occupational therapist; the FIM™ and the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) were administered by the CAReS data collector.

Instruments

Safety of the stroke survivor in the home environment was measured by using the SAFER Tool (Chiu et al., 2001) which is a home safety assessment developed by occupational therapists that targets the elderly population with cognitive and/or physical disabilities living at home (Backman, 2002; Chiu et al., 2001; Oliver, Chiu, Marshall, & Goldsilver, 2003). It is administered through an interview checklist, task analysis, as well as observations within the home and takes approximately 60–90 minutes to perform (Backman 2002; Chiu et al., 2001; Oliver et al., 2003). This assessment was devised to evaluate the ability of clients to safely carry out occupational performance tasks in the home environment and to evaluate the home environment as well (Backman, 2002; Chiu et al., 2001; Oliver et al., 2003). Observations are made on 97 items in 14 categories: living situation, mobility, kitchen, fire hazards, eating, household, dressing, grooming, bathroom, medication, communication, wandering, memory aids, and general (Backman, 2002; Chiu et al., 2001; Oliver et al., 2003).

Chiu et al. (2001), Oliver et al. (2003) and Lysack (2005) report that the internal consistency reliability of the SAFER Tool is excellent; Letts et al. (1994) report that internal consistency reliability has been established [KR-20 coefficient = 0.83] (Chiu et al., 2001; Letts & Marshall, 1995; Lysack, 2005). Chiu et al. and Oliver et al. report very good inter-rater reliability, while Letts, Scott, Burtney, Marshall and McKean (1998) report apparently acceptable inter-rater reliability on 59 out of 66 items [k=.61 or higher on more than 71% of items using kappa statistic; 90% agreement or higher on 87% of items using percentage agreement] (Chiu et al., 2001; Letts et al., 1998). Chiu et al. and Oliver et al. report very good test-retest reliability, while Letts et al. (1998) report apparently acceptable test-retest reliability [k=.61 or higher on more than 75% of items using kappa statistic; 90% agreement or higher on 100% of items using percentage agreement] (Chiu et al., 2001; Letts, et al., 1998). Content validity of the SAFER Tool has been verified (Oliver et al., 2003; Letts & Marshall, 1995). Chiu et al., Letts et al., Letts and Marshall (1995), and Letts, Marshall and Cawley (1995) report that the construct validity of the SAFER Tool is in need of further investigation.

The FIM™ is an 18-item instrument which measures performance in self-care, sphincter control, transfers, locomotion, communication, and social cognition on a 7 point scale (1= total assistance; 7= complete independence). The range of total scores is from 18 to 126; higher scores indicate more independent functioning (Ostwald, Swank & Khan, 2008; Wright, 2000). The FIM ™ has been determined to be a reliable measure [Cronbach's α = 0.93] (Dodds, Martin, Stolov, & Deyo, 1993; Ostwald, Swank, et al., 2008;). It has been found to have discriminative value and be useful in the evaluation of individuals post stroke (Dodds et al., 1993; Granger, Cotter, Hamilton, & Fiedler, 1993; Ostwald, Swank, et al., 2008;). Interrater reliability for the total FIM™ has been found to be high [ICC= 0.96] (Hamilton, Laughlin, Fiedler, & Granger, 1994). The internal consistency reliability coefficient (Cronbach's α) for the FIM™ in the CAReS study was 0.95.

The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) was designed specifically to assess depression in older adults and has a cutoff for significant depressive symptoms of 4/5 (D'Ath, Katona, Mullan, Evans, & Katona, 1994; Ostwald, Swank, et al., 2008; Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986). The GDS-15 has been demonstrated to have a high level of internal consistency [Cronbach's α = 0.80] (D'Ath et al., 1994; Ostwald, Swank, et al., 2008). The internal consistency reliability coefficient (Cronbach's α) for the GDS-15 in the CAReS study was 0.76.

Demographic data

Demographic data were obtained from the CAReS database on age, gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES), which was measured by the Hollingshead SES Tool (Hollingshead, 1979). Data on the type and location of the stroke, functional status, and depression scores were also obtained for descriptive purposes.

Data collection procedures

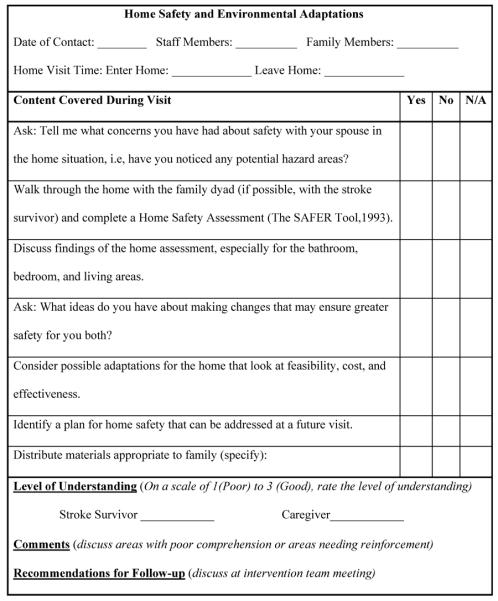

As part of the home-based intervention, the occupational therapist used a Home Safety and Environmental Adaptation Protocol (see Figure 1) of which the SAFER Tool was a major component in assessing the home environment, identifying problems, and offering recommendations to the dyad. Data were collected through direct questions and observations of the home. Each assessment took approximately 60 to 90 minutes and was completed in the home with both the stroke survivor and caregiver present. Following the visit, information on the visit was entered into the Home Safety Protocol form.

Figure 1.

Protocol for Home Safety and Environmental Adaptations

During the administration of the SAFER Tool, findings were entered onto the SAFER Tool along with comments. The scoring form had three columns- “A” for “addressed”, meaning the therapist addressed the item, but no problem was noted; “N/A' for “not applicable”, indicating the item did not apply to the participant's environment; and “P” for “problem”, scored with a check and described on the form. Because the SAFER Tool considers the transaction between the individual and their environment relative to the individual's safety (Letts et al, 1994; Letts et al., 1995; McNulty & Fisher, 2001), deciding whether or not an item was a problem depended upon the interaction of the stroke survivor with the caregiver in the environment. If the caregiver completed the entire item for the stroke survivor (for example, cooking a meal) the item was not identified as a problem. When the assessment was completed, all problem areas were discussed with the dyad and recommendations were made. The occupational therapist collaborated with the dyad to explore the feasibility of implementing the recommendations. If another appointment was thought to be needed, a follow up visit was scheduled. Community resources were also suggested when the dyad lacked financial or technical resources.

Data Analysis

The SAFER Tool was scored by counting the number of problems identified for each participant and summed providing an overall total score. From this, an average total score for all 76 participants was computed. A mean sub-score for each of the 14 categories was also determined for all 76 participants. SAS v9.1 was used to calculate descriptive statistics and to test correlations between the SAFER Tool scores and gender, ethnicity, age, location of stroke, functional status, and depression.

Findings

Demographics of the Participants

The demographics for the 76 stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers, as well as stroke-related variables are shown in Table 1. The average age was 67 years and only 31.6% of the sample were female.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Stroke Survivors Completing the SAFER Tool (n=76)

| Characteristic | Mean | Std.Dev. | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Baseline | 66.95 | 9.24 | 50.05–87.56 |

| Socioeconomic Status | 44.17 | 12.15 | 16.5–66.0 |

| Depression | 4.45 | 2.88 | 0–12 |

| Functional Status | 86.13 | 23.67 | 22–124 |

| n | %* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 52 | 68.4 |

| Female | 24 | 31.6 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | African American | 14 | 18.4 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Caucasian | 44 | 57.9 | |

| Hispanic | 12 | 15.8 | |

| Mixed/Other | 4 | 5.3 | |

| Mechanism | Hemorrhage | 19 | 25 |

| Thrombus | 53 | 69.7 | |

| Location | Basal Ganglia | 1 | 1.3 |

| Bilateral | 13 | 17.1 | |

| Left | 24 | 31.6 | |

| Right | 36 | 47.4 |

may not sum to 100% due to missing data

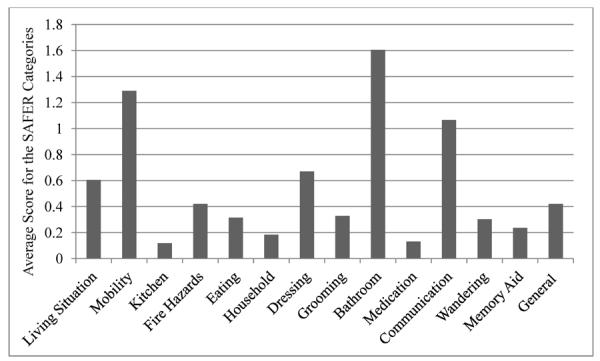

The average score, i.e. the number of identified problems, obtained on the SAFER Tool for the 76 stroke survivors was 7.7. Figure 2 illustrates the 14 categories addressed by the SAFER Tool and the average score for each category for this sample of stroke survivors. The three most problematic categories for this sample were bathroom activities, mobility and communication, with a range of one to two problems in each of these categories. On average, participants experienced more than one problem in the categories of bathroom, mobility, and communication, with a smattering of problems across the other categories. In the category of bathroom, the most common recommendation was for grab bars; in the category of mobility, the primary recommendation was referral for driving evaluation and information; and in the category of communication, the predominant recommendation was for a personal emergency services (PERS) system. No statistically significant correlations were found between the scores or sub-scores on the SAFER Tool and gender, ethnicity, age, location of stroke, functional status or depression.

Figure 2.

Average Score for the 14 Categories of the SAFER Tool

Table 2 illustrates the types of recommendations made for each of the 14 SAFER Tool categories. The second column in the final row of the table illustrates the topics covered and recommendations made during education of the stroke survivor and spousal caregiver.

Table 2.

Recommendations Made According to the 14 SAFER Tool Categories and for Caregiver Education

| Category | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Living situation | remove scatter rugs, remove barriers, railing on stairs, protect from sharp edges, floor surface hazards |

| Mobility | driving evaluation, UE/LE support and positioning, equipment: wheelchair/ walker/ cushion, bed rails, transfers, night light, sturdy shoes, bed positioning, standing tolerance, remove clutter |

| Kitchen | 1 handed cutting board and can opener, kitchen cart |

| Fire Hazards | smoke detectors: batteries/ reconnect/ install |

| Eating | non-slip mat for plate, scoop dish, plate guard, eating devices |

| Household | resume simple cooking tasks |

| Dressing/Grooming | given instructions, front bra fasteners, hook-and-loop fastener on shoes, use smooth edge razor, shampoo techniques, perform self-care in bathroom |

| Bathroom | grab bars, raised toilet seat, replace glass doors, shower strips/mat, continence routine, bedside commode, shower chair, shower extension, nonslip rugs, address bathroom remodeling, toilet hygiene device, U bar/toilet bars, diff. portable toilet, adjust doorjamb to widen doorway, soap mitt/dish |

| Medication | dosette |

| Communication | PERS, writing exercises: lined paper/ pencil grip, mobile phone |

| Wandering | medic alert or ID |

| Memory Aids | memory cues |

| General | resume leisure activities, recommend community programs, left side neglect safety/scan environment, treadmill exercise, computer use/reading paper, smoke cessation program, encourage book tapes/music, splint wear schedule, referral to physician for pain/numbness, referral for home care assistance, referral for van adaptations, referral for quilter, referral for further medical and rehabilitation intervention, referral for physical therapy consult, check with gas company regarding water and heater, resume therapy/walking/UE exercise |

| Caregiver Education | self care tasks, incontinence routine, wheelchair in car, referral for used equipment, recommend supervised care, encourage independence in ADLs, referral for home health intervention/nursing |

Case Studies

Two case studies follow to illustrate the use of the SAFER Tool with this sample of stroke survivors. The names of the participants have been changed to protect confidentiality. In the case studies, the names of the categories in which stroke survivors were noted to have problems are in italics with the number of problems within that category following in parentheses.

Case Study I

Mr. Jackson was a 62 year-old African American male who experienced a left brain cerebrovascular accident (CVA) resulting in right hemiplegia. He and his 54 year-old spousal caregiver lived in a three bedroom one story rental home. He was employed as a truck driver and was functionally independent prior to his stroke. His spouse was a nurse's aide and did in-home care about 4 days a week. Following his stroke, Mr. Jackson was usually by himself during these times. A daughter would be in and out and assist her father as needed and drive him to appointments. Mr. Jackson had two sons from a previous marriage and the younger son did visit him. This was a second marriage for both Mr. Jackson and his current spouse and between them they had two daughters, one age 23 and one age 36. His spouse was present for the assessment and the 23 year old daughter joined in later.

Mr. Jackson obtained a score of 12 on the SAFER Tool. In the category of living situation (1), the home was found to be organized and clean, but had a few environmental safety issues having to do with limited space for maneuverability with cane or wheelchair and with scatter rugs. In the living room, there was a narrow pathway between the sofa and the coffee table. Mr. Jackson also needed more room in the bedroom to maneuver between the bed and the dresser. There were many scatter rugs in the living room as well as on the kitchen floor. These issues posed potential dangers for tripping and falling, although Mr. Jackson reported that he knew to look and find his step and he did not acknowledge these issues as problematic. In the category of mobility (2), he had fallen and wanted to resume driving but was unable to due to his limited motion on the right side. In the category of fire hazards (1), the hallway smoke detector needed batteries. In the category of household (2), Mr. Jackson could manage frozen meals but wanted to resume preparing meals; he had difficulty carrying items and there was no transport cart for him to use while he prepared his breakfast in the morning. In the category of bathroom (3), Mr. Jackson had a seating aid, but there was no shower extension, there were no grab bars in the shower tub, and there was no non-slip mat in the tub. There was also no raised toilet seat or grab bar near the toilet. He used a urinal when sitting in the living room or sitting outside. In the category of communication (2) Mr. Jackson had some clumsiness with managing the phone with his left hand and his speech was somewhat slurred but intelligible. He also had no personal emergency services (PERS) system. No problems were identified in the other seven categories: kitchen, eating, dressing, grooming, medication, wandering, memory aids and general. Suggestions were made to remove obstacles, widen pathways for safer maneuverability, and incorporate bathroom safety equipment, but these were not followed through by the family. They did accept the following recommendations: incorporate a kitchen cart to transport items, obtain a PERS system or carry a cell phone on him, continue with his upper extremity exercises, and see about a driver rehabilitation evaluation.

Case Study II

Mr. Watts was a 69 year-old Caucasian male who experienced a left brain CVA with resulting right hemiplegia. He was a retired electrical contractor and an inspector. He lived with his spouse and six-year-old granddaughter in a two-story home with the master bedroom and bathroom on the first floor; he and his spouse had lived there for 11 years. Mr. Watts was functionally independent and working part-time prior to his stroke. After the stroke, he incurred right hemiplegia leaving him unable to use his right upper extremity. He was using a wheelchair for mobility. He received both inpatient and outpatient therapy post stroke.

Mr. Watts obtained a score of 12 on the SAFER Tool. In the category of living situation (1) there was limited access to the home but the living space was found to be uncluttered and clean. A short ramp at the front entrance and a raised ramp between the kitchen and garage were in need of reconstruction. In the category of mobility (1) Mr. Watts required maximum assist for transfers but manipulated his wheelchair independently. In the category of household (2) he wanted to resume some simple meal preparation, cleanup, and financial management tasks which were problematic due to his weakness in the upper extremity and lack of endurance. In the category of dressing (1) he required moderate assistance with his shoes. In the category of bathroom (4), Mr. Watts required maximum assistance of two for shower transfers (tub was too deep for transfers with a bench); there was a shower chair but no grab bars present, and he used a portable toilet as the toilet was not raised and had no grab bars. In the category of communication (2), Mr. Watts' speech was noted to be slurred and slow, but improving; reading was difficult. In the category of general (1) he reported that his leisure activities were limited. No problems were identified in the other seven categories: kitchen, fire hazards, eating, grooming, medication, wandering and memory aids. Recommendations included continuing right upper extremity exercises, repair of the 2 ramps, hook-and-loop fasteners on shoes, and resumption of reading the weekend paper; the stroke survivor and caregiver completed these suggestions in time. Specific recommendations for the bathroom area were noted on the equipment protocol and followed through by the family.

Discussion

Results from our descriptive analysis of the SAFER Tool administered to stroke survivors and their spouses provide insights into the value of home safety assessments and the benefits to clients in identifying barriers to successful occupational performance. The following discussion of these points will highlight features of the SAFER Tool with our sample, implications for occupational therapy, suggestions for future research, and the study's limitations.

SAFER Tool Scores and Identified Problem Areas

The average score obtained on the SAFER Tool for the 76 stroke survivors of 7.7 is similar to the SAFER Tool mean of 7 reported by Chiu et al. (2001). However, only 8% of Chiu and colleagues' sample had experienced a stroke; the remainder of their sample had dementia, depression, frailty and hip fractures. Our sample was younger (67 years versus 78 years). In addition, our sample had only 31.6% females as compared to 70% in their sample.

The SAFER Tool scores identified that the greatest problems were in the categories of bathroom, mobility, and communication. Corresponding to those three categories were the recommendations made to the clients. For example, in the category of bathroom, the most common recommendation was for grab bars; in the category of mobility, the primary recommendation was referral for driving evaluation and information; and in the category of communication, the predominant recommendation was for a PERS system. The SAFER Tool is a thorough assessment covering both BADLs and IADLs. The directions for administration are quite clear and the tool is easy to administer. It is time efficient and offers information that allows the occupational therapist administering the tool to make needed recommendations. The clinical utility of this tool has also been reported by Chiu and Oliver (2006), Letts et al. (1994), Letts et al. (1998), and Lysack (2005). These recommendations provide strategies by which the occupational therapist can suggest approaches that ensure safer performance in the identified problematic categories. Consequently, the stroke survivor is able to safely perform his or her daily activities; and in so doing the caregiver is relieved of that additional burden.

Caregiver Impact

All of the participants in the study had a spousal caregiver present in the home, and their presence might have had an influence on participants' scores on the SAFER Tool. For instance, when an individual obtained a low score on the SAFER Tool, it was not necessarily an indication of functional independence as narrowly defined by the rehabilitation/medical model; rather, it may have indicated that the caregiver completed the task and/or supervised the stroke survivor (Hinojosa, 2002). In other words, a stroke survivor who was unable to do any kitchen tasks and independently or properly maintain items in that environment would receive a “no problem” score in that category since the spouse was handling all those areas assessed in that category. The assessment would have had quite a different outcome if the stroke survivor had no spouse or the spouse was unable to do necessary tasks that the stroke survivor could not do safely on his or her own.

The interaction between person and social and physical aspects of the environment is supported in the theoretical foundation of the SAFER Tool (Chiu & Oliver, 2006) which reflects concepts from the Occupational Adaptation Model (Letts & Marshall, 1995; Schkade & Schultz, 1992; Schultz & Schkade, 1992) as well as Lawton and Nahemow (1973) [Letts & Marshall, 1995]. These theorists consider the transaction between the individual and the environment as having a significant influence on the person's adaptation and occupational performance (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973; Letts & Marshall, 1995; Schkade & Schultz, 1992; Schultz & Schkade, 1992). With that in mind, the presence of the caregiver dynamically would modify the environment and task at hand.

Implications for Occupational Therapy

The role of the occupational therapist in this study was to combine clinical judgment with results of the SAFER Tool to determine if the individual was safe in the current home environment. Like any assessment, the tool alone did not provide a complete picture of the home situation and the skills and deficits of the client. Clinical judgment is developed over many years of experience working with individuals in the home situation. No matter what assessment is used, it should be noted that experience and interactive clinical reasoning as a means of individualizing intervention (Fleming, 1991) play a large role in the assignment and interpretation of assessment scores.

Occupational therapists play an essential role with a team of health care providers involved in the rehabilitation of stroke survivors. Trombly and Ma (2002) indicate that those who receive occupational therapy training have greater improvement in areas of role participation, IADLs and BADLs than those who do not receive these services. Occupational therapy aims at refining skills that are present as well as introducing new techniques and adaptive skills for approaching everyday activities. In this study, occupational therapy contributed to the safety education of stroke survivors and caregivers in three major areas-bathroom activities, mobility, and communication- as well as provided recommendations about assistive devices.

Caregiver Education

An integral part of occupational therapy intervention in this study was the caregiver who played a significant role in the daily life of the stroke survivor. The caregiving situation included three essential components, forming a triad of the caregiver, client/care recipient (in this case, the stroke survivor), and the formal caregiver, the therapist (Hersch, 1991). It became a collaborative effort between all three parties having an equal role in the intervention process. Sharing ideas, problem solving together, and coming to agreement on solutions were important ingredients contributing to a successful outcome.

Suggestions for Future Research and Public Policy

The results of a home safety assessment such as the SAFER Tool can be an important catalyst for caregiver education and a springboard for much needed recommendations. Education was the main focus of the CAReS study, and occupational therapy included caregiver education as part of the home safety program. We found education and psychosocial support in the home setting to be essential for stroke survivors and their families. Often, however, there is no funding for such follow up. This study has implications for public policies that provide funding for post-discharge assessments and involvement of occupational therapists to decrease frequent complications of stroke, such as falls and isolation due to environmental problems. The area of post-discharge care for stroke survivors and their families is one that is in great need of research, development, and implementation.

Based on an extensive literature review of the usability of the SAFER Tool, this is the first study to report on use of the second version of the SAFER Tool (Chiu et al. 2001) solely with stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers. Further research is needed on the use of this tool and later versions with this population.

Limitations

In terms of the study's limitations, the recommendations might not be representative of a typical stroke population. In addition, there was a wide range of time post stroke for when participants were recruited into the study and visited by the intervention team. This wide variation could have had an effect on SAFER Tool, FIM™ and GDS-15 scores as some participants could have been assessed three months post stroke while others could have been assessed nine months post stroke. Scoring with the SAFER Tool on follow up was not enacted in the form of a pretest/ posttest design. More accurate records of falls would have been helpful.

Conclusion

Safety in the home environment is an important concern for stroke survivors and their caregivers as they transition to living in their home and community. In this study, the SAFER Tool was significant in determining the safety of stroke survivors with spousal caregivers in the home and a useful springboard for recommendations. In combination with the therapist's clinical judgment, the SAFER Tool maximized the occupational performance of the stroke survivor. Working together, the occupational therapist, stroke survivor, and caregiver were able to reach mutually beneficial goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Karen Janssen, MSN, RN for data collection and all the other CAReS team members. A special thanks is extended to the stroke survivors and their caregivers who participated in the study.

Declaration of Interest This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Nursing Research R01 NR005316 (Sharon K. Ostwald, PI) and the Isla Carroll Turner Friendship Trust.

References

- American Heart Association Heart disease and stroke statistics: Our guide to current statistics and the supplement to our heart & stroke facts: 2010 update-at-a-glance. 2010 Retrieved from American Heart Association website: http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1265665152970DS-3241%20HeartStrokeUpdate_2010.pdf.

- Backman C. SAFER Tool: Safety Assessment of Function and the Environment for Rehabilitation (2001). [Review of the book Safety Assessment of Function and the Environment for Rehabilitation manual, by T. Chiu, R. Oliver, L. Marshall, & L. Letts] Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;69:303. doi: 10.1177/000841749306000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Stroke facts. 2010 Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: http://www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm.

- Chiu T, Oliver R. Factor analysis and construct validity of the SAFER-HOME. OTJR: Occupation, Participation & Health. 2006;26:132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu T, Oliver R, Marshall L, Letts L. Safety Assessment of Function and the Environment for Rehabilitation Tool Manual. Comprehensive Rehabilitation and Mental Health Services; Toronto: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Smith DS. Psychological correlates of outcome following rehabilitation from stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation. 1999;13:129–140. doi: 10.1191/026921599673399613. doi: 10.1191/026921599673399613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PC, Marshall V, Black SE, Colantonio A. Well-being after stroke in Canadian seniors. Stroke. 2002;33:1016–1021. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000013066.24300.f9. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000013066.24300.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ath P, Katona P, Mullan E, Evans S, Katona C. Screening, detection and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders. I: The acceptability and performance of the 15 item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15) and the development of short versions. Family Practice. 1994;11:260–266. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.3.260. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds TA, Martin DA, Stolov WC, Deyo RA. A validation of the Functional Independence Measurement and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1993;74:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90119-u. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90119-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MH. The therapist with the three-track mind. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991;45:1007–1014. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.11.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen G. A comparison of situational and dispositional coping after a stroke. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 2006;22(2):31–59. doi: 10.1300/J004v22n02_02. [Google Scholar]

- Granger CV, Cotter AC, Hamilton BB, Fiedler RC. Functional assessment scales: a study of persons after stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1993;74:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Grypdonck M. Being a stroke patient: A review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;26:580–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-19-00999.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-19-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BB, Laughlin JA, Fiedler RC, Granger CV. Interrater reliability of the 7- level Functional Independence Measure (FIM) Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 1991;26:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch GI. Perspectives of the caregiving relationship by older adults and their family members (Doctoral dissertation) University Microfilms International Dissertation Express; 1991. Retrieved from. Order No. 9217391. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa J. Position paper: Broadening the construct of independence. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56:660. doi: 10.5014/ajot.56.6.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. 1979 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Jones VN. The forgotten survivor. 2006 Retrieved from the National Stroke Association website: http://www.stroke.org/site/PageServer?pagename=SS_MAG_so2006_feature_forgot.

- Jørgensen l., Engstad T, Jacobsen BK. Higher incidence for falls in long-term stroke survivors than in population controls. Stroke. 2002;33:542–547. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.102375. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.102375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley CP, Graham C, Christy JB, Hersch G, Shaw S, Ostwald SK. Falling and mobility experiences of stroke survivors and spousal caregivers. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2010;28(3):235–248. doi:10.3109/02703181.2010.512411. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Nahemow L. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfer C, Lawton MP, editors. The psychology of adult development and aging. American Psychological Association; Washington, D. C.: 1973. pp. 619–674. doi: 10.1037/10044-020. [Google Scholar]

- Letts L, Law M, Rigby P, Cooper B, Stewart D, Strong S. Person-environment assessments in occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1994;48:608–618. doi: 10.5014/ajot.48.7.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letts L, Marshall L. Evaluating the validity and consistency of the SAFER Tool. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 1995;13(4):49–66. doi:10.1080/J148v13n04_05. [Google Scholar]

- Letts L, Marshall L, Cawley Assessing safe function at home: The SAFER Tool. Home & Community Health Special Interest Section Newsletter. 1995;2(1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Letts L, Scott S, Burtney J, Marshall L, McKean M. The reliability and validity of the Safety Assessment of Function and Environment for Rehabilitation (SAFER Tool) British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998;61:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lysack C. The SAFER Tool: For every OT's tool belt! Gerontology Special Interest Section Quarterly. 2005;28(2):4. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty MC, Fisher AG. Validity of the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills to estimate overall home safety in persons with psychiatric conditions. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;55:649–655. doi: 10.5014/ajot.55.6.649. doi: 10.5014/ajot.55.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonnekes JH, Talelli P, de Niet M, Reynolds RF, Weerdesteyn V, Day BL. Deficits underlying impaired visually triggered step adjustments in mildly affected stroke patients. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2010;24:393–400. doi: 10.1177/1545968309348317. doi: 0.1177/1545968309348317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver R, Chiu T, Marshall L, Goldsilver Home safety assessment and intervention practice. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2003;10:144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald SK, Bernal MP, Cron SG, Godwin KM. Stress experienced by stroke survivors and spousal caregivers during the first year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2009;16:93–104. doi: 10.1310/tsr1602-93. doi:10.1210/tsr1602-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald SK, Davis S, Hersch G, Kelley C, Godwin KM. Evidence-based educational guidelines for stroke survivors after discharge home. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2008;40:173–191. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200806000-00008. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200806000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald SK, Swank PR, Khan MM. Predictors of functional independence and stress level of stroke survivors at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2008;23:371–377. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317435.29339.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: Applications to practice. Pearson Education, Inc; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pulaski KH. Adult neurological dysfunction. In: Crepeau E, Cohn E, Schell B, editors. Willard and Spackman's Occupational Therapy. 10th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2003. pp. 767–788. [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. Accessibility and usability of the physical housing environment of seniors with stroke. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2004;27:203–208. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200409000-00005. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowles G. A place to call home. In: Carsten LL, Edelstein BA, editors. Handbook of clinical gerontology. Pergamon Press; New York: 1987. pp. 335–353. [Google Scholar]

- Schkade J, Schultz S. Occupational adaptation: Toward a holistic approach for contemporary practice, part 1. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1992;46:829–837. doi: 10.5014/ajot.46.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz S, Schkade J. Occupational adaptation: Toward a holistic approach for contemporary practice, part 2. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1992;46:917–925. doi: 10.5014/ajot.46.10.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz CH, Wasserman J, Ostwald SK. Recruitment and retention of stroke survivors: The CAReS experience. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2006;25(1):17–29. doi: 10.1080/J148v25n01_02. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, editor. Clinical gerontology: A guide to assessment and intervention. The Haworth Press; New York: 1986. pp. 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Trombly CA, Ma H. A synthesis of the effects of occupational therapy for persons with stroke, part I: Restoration of roles, tasks, and activities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56:250–259. doi: 10.5014/ajot.56.3.250. doi:10.5014/ajot.56.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. The FIM™. The Center for Outcome Measurement in Brain Injury. 2000 doi: 10.1097/00001199-200002000-00011. Retrieved from http://www.tbims.org/combi/FIM. [DOI] [PubMed]