Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Changes in gut microbiota have been reported to alter signaling mechanisms, emotional behavior, and visceral nociceptive reflexes in rodents. However, alteration of the intestinal microbiota with antibiotics or probiotics has not been shown to produce these changes in humans. We investigated whether consumption of a fermented milk product with probiotic (FMPP) for 4 weeks by healthy women altered brain intrinsic connectivity or responses to emotional attention tasks.

METHODS

Healthy women with no gastrointestinal or psychiatric symptoms were randomly assigned to groups given FMPP (n = 12), a nonfermented milk product (n = 11, controls), or no intervention (n = 13) twice daily for 4 weeks. The FMPP contained Bifidobacterium animalis subsp Lactis, Streptococcus thermophiles, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Lactococcus lactis subsp Lactis. Participants underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging before and after the intervention to measure brain response to an emotional faces attention task and resting brain activity. Multivariate and region of interest analyses were performed.

RESULTS

FMPP intake was associated with reduced task-related response of a distributed functional network (49% cross-block covariance; P = .004) containing affective, viscerosensory, and somatosensory cortices. Alterations in intrinsic activity of resting brain indicated that ingestion of FMPP was associated with changes in midbrain connectivity, which could explain the observed differences in activity during the task.

CONCLUSIONS

Four-week intake of an FMPP by healthy women affected activity of brain regions that control central processing of emotion and sensation.

Keywords: Stress, Nervous System, Yogurt

A growing body of preclinical evidence supports an important influence of gut microbiota on emotional behavior and underlying brain mechanisms.1– 4 Studies in germ-free mice have demonstrated the important role of gut microbiota in brain development and resultant adult pain responses and emotional behaviors, as well as on adult hypothalamic-pituitary axis responsiveness.2,4 – 6 Alteration of the normal gut flora in adult rodents with fecal transplants, antibiotics, or probiotics has also been reported to modulate pain and emotional behaviors as well as brain biochemistry.1,2,7–10 These findings have led to the provocative suggestion that the gut microbiota might have a homologous effect on normal human behavior and that alterations in their composition, or in their metabolic products can play a role in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disease or in chronic abdominal pain syndromes, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).11–14 However, in contrast to the strong preclinical evidence linking alterations in gut microbiota to emotional behavior, there is only suggestive evidence that a similar relationship might exist in humans.3,15–17

Many reports have provided evidence for effects of probiotics on gut function and visceral sensitivity.18,19 For example, various strains of probiotics have been demonstrated to reduce visceral nociceptive reflex responses in rodents and human symptoms of abdominal discomfort; however, the mechanism(s) underlying these effects remain poorly understood.8,20 –27 In addition to various suggested peripheral mechanisms, alteration in central modulation of interoceptive signals, including the engagement of descending bulbospinal pain modulation systems, or ascending monoaminergic modulation of sensory brain regions, can also play a role.28,29 Alterations in such endogenous pain-modulation systems have been implicated in the pathophysiology of persistent pain syndromes, such as IBS and fibromyalgia.30 –32

There are many potential signaling mechanisms by which gut microbiota and probiotics could influence brain activity, including changes in microbiota-produced signaling molecules (including amino acid metabolites, short chain fatty acids, and neuroactive substances), mucosal immune mechanisms, and enterochromaffin cell–mediated vagal activation.12,33–37 In rodent studies, altered afferent vagal signaling to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) has been reported in response to intestinal pathogens and probiotics.1,38 – 40 From the NTS, viscerosensory signals propagate to pontine nuclei (locus coeruleus, raphe nuclei, parabrachial nucleus), midbrain areas (periaqueductal gray), forebrain structures (amygdala, hypothalamus), and cortical regions (insula, anterior cingulate cortex), illustrating a plausible pathway for the ascending limb of such microbiota-influenced modulation systems. In addition, ascending monoaminergic projections from the NTS, locus coeruleus, and raphe nuclei can modulate a wide range of cortical and limbic brain regions, thereby influencing affective and sensory functions.41

In the current study, we hypothesized that, in homology to the preclinical findings, reactivity to an emotional attention task and underlying brain circuits in humans can be influenced by gut to brain signaling, and that a change in the gut microbiota induced by chronic probiotic intake can alter resting-state brain connectivity and responsiveness of brain networks to experimental emotional stimuli. One mechanism of widespread probiotic-induced brain activity changes might be vagally mediated ascending monoaminergic modulation of multiple brain areas, including affective and sensory regions.

We acquired evoked and resting-state brain responses using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in a group of healthy women before and after 4-week consumption of a fermented milk product with probiotic (FMPP). The imaging paradigm chosen is a standardized emotional faces attention task, which measures rapid, preconscious, and conscious brain responses to emotional stimuli.42,43 The task engages widespread affective, attentional, sensory, and integrative brain regions that likely act as a rapid preconscious regulatory system engaged to prepare for potentially threatening situations. The response to this task is altered in anxiety disorders and is partially dependent on serotonergic signaling.44,45 The task is well suited to assess subtle changes in emotional regulation, which can be analogous to those behavioral changes noted in preclinical models. The specific FMPP was chosen because of preclinical evidence demonstrating a reduction in reflex responses to noxious visceral stimuli, and reports of beneficial effects on gastrointestinal symptoms in healthy people and IBS patients.20,24,46,47

Methods

Study Design

The study used a single center, randomized, controlled, parallel-arm design. One intervention group (FMPP) and 2 control groups were utilized: a nonfermented control milk product (Control) to allow differentiation of specific treatment responses from those due to potential changes from increase in dairy ingestion or anticipation of improved well being, and a no-intervention group to allow us to control for the natural history of brain responses over time. Subjects were screened for eligibility at visit 1, had a 2-week run in period, then underwent fMRI followed by randomization that was determined by an external contract research organization and coordinated with the UCLA Clinical Research Center, independently of the investigators. The FMPP and Control arms were double-blinded. The subjects had a repeat fMRI visit 4 weeks after intervention initiation (±2 days).

Subject Criteria

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Subjects were healthy women, aged 18 to 55 years, who were recruited by advertisement. The Supplementary Material contains detailed exclusion criteria. Subjects could not have taken antibiotics or probiotics in the month before the study and were willing to avoid use of probiotics for the duration of the study. During the 2-week run-in period, subjects completed a daily electronic diary of gastrointestinal symptoms. Subjects reporting abnormal stool form (Bristol stool scale 1, 6, or 7) or frequency (>3 bowel movements per day or <3 bowel movements per week) or abdominal pain/discomfort on more than 2 days were excluded. This careful screening for gastrointestinal symptoms was performed with the goal of isolating FMPP effects on emotional systems, rather that observing secondary changes due to potentially observable improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms. To avoid possible effects of ingestion of a nonallowed probiotic either on entry or during the intervention period, subjects with Bifidobacterium lactis present in the stool at baseline, as well as subjects in the Control and No-Intervention groups, who had B lactis in the stool at study completion, were excluded.

Study Products and Administration

FMPP was a fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis (strain number I-2494 in French National Collection of Cultures of Micro-organisms (CNCM, Paris, France), referred as DN-173 010 in a previous publication,23 together with the 2 classical yogurt starters, Streptococcus thermophilus (CNCM strain number I-1630) and Lactobacillus bulgaricus (CNCM strain numbers I-1632 and I-1519), and Lactococcus lactis subsp lactis (CNCM strain number I-1631). The test product contains 1.25 × 1010 colony-forming units of B lactis CNCM I-2494/DN-173 010 per cup and 1.2 × 109 colony-forming units/cup of S thermophilus and L bulgaricus. The nonfermented Control milk product was a milk-based nonfermented dairy product without probiotics and with a lactose content of <4 g/cup, which is similar to the content of lactose in the test product. The Control product was matched for color, texture, taste, calories, protein, and lipid content to the FMPP. Both products were provided in 125-g pot, consumed twice daily. The product was prepared at Danone Research facilities and shipped in blinded packaging to the UCLA Clinical Research Center. Daily compliance was measured by an automated phone system. Compliance of <75% led to exclusion from the study.

Stool Analysis

Stool samples were collected pre and post intervention. Fresh samples were stored in RNA synthesis stabilization buffer (RNA Later; Ambion, Austin, TX) at the time of collection. A centrifuged fecal pellet was stored at −80°C. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction for B lactis was performed in duplicate for each subject sample and normalized to total bacterial counts. Values were evaluated as either above or below the detection threshold. A post-hoc analysis of fecal microbiota via high-throughput pyrosequencing was performed (Roche FLX Genome Sequencer; Basel, Switzerland). Polymerase chain reaction primers used to profile fecal microbiota targeted the V5 and V6 16S RNA region.

Neuroimaging Acquisition and Analysis

Imaging was performed on a Siemens 3 Tesla scanner (Siemens, New York, NY). Functional scans used a TR of 2500 ms, TE of 26 ms, flip angle of 90 degrees, slice thickness of 3.0 mm. SPM8 (Statistical Parametric Mapping) was used for data analysis. A 5-minute, eyes-closed, resting scan was performed first. A standardized emotional faces attention task for fMRI was then performed.48,49 During the task, the subject matched validated negative affect (fear and anger) faces with 1 of 2 additional faces shown below it, using a button press (match emotions [ME]).50 The control task used geometric forms instead of faces for the matching task (match forms [MF]). Each matching trial was 5 seconds and 20 trials of each condition (ME and MF) were performed in 4 randomized blocks.

Images were co-registered, normalized, and smoothed with an 8-mm Gaussian kernel. Subject-level analyses based on changes in blood oxygenation level– dependent (BOLD) contrasts were performed in SPM8. First-level models included motion realignment regressors and high-pass filtering. Task activity (ME-MF) was assessed at baseline using whole brain and region of interest analysis with small volume correction (see Results in Supplementary Material). Partial least squares analysis (PLS, http://www.rotman-baycrest.on.ca) was applied to task time series across the 3 groups and 2 conditions (pre and post intervention) to identify possible effects of the FMPP on functional connectivity during the task (“task PLS”).51,52 Voxel reliability was determined using bootstrap estimation (500 samples). The ratio of the observed weight to the bootstrap standard error was calculated and voxels were considered reliable if the absolute value of the bootstrap ratio exceeded 2.58 (approximate P < .01). Clusters >20 voxels are reported. The task PLS analysis produced a spatial map in which voxel weights indicated the magnitude and direction of group differences in intervention response. To test intervention effects on individual regions, SPM’s image calculator tool was used to generate statistical parametric difference maps between pre and post intervention. Subsequently, 2-sample t tests were performed to compare responses between groups. Small volume corrections were performed in the amygdala, insula subregions, and somatosensory regions (Brodmann 2 and 3) and a whole-brain analysis was performed, both using a significance level of P < .05 with family-wise error correction for multiple comparisons.

To determine whether the intervention-related changes observed in the task analysis were correlated with resting-state brain activity after intervention, resting scan correlation maps were calculated in SPM using the peak voxel from 3 clusters of interest in the Task PLS as seeds. The midbrain, insula, and the somatosensory cortex (Supplementary Material) clusters were selected due to our hypothesis that the change in gut microbiota would lead to alterations in viscerosensory signaling, mediated through brainstem responses. A seed PLS was then performed for each region of interest using the seed-based correlations maps and the functional activity from the ME-MF task at the source voxel. Voxel reliability was determined as mentioned here.

Diary and Symptom Data

Gastrointestinal and mood symptoms were assessed and analyzed using a general linear mixed model as described in the Supplementary Material.

Safety Data

Adverse events were recorded at each visit and on an ad-hoc basis. World Health Organization– based System Organ Classification was used.

Hormonal data

Salivary estrogen and progesterone levels were measured at each MRI scan day and groups compared using analysis of variance.

Results

Mean subject age was 30 ± 10.4 years (range, 18 –53 years) and mean body mass index was 22.8 ± 2.7. Twelve female subjects completed intervention with FMPP, 11 with a nonfermented milk control product (Control), and 13 had no intervention. One FMPP subject was excluded for product noncompliance (negative stool B lactis quantitative polymerase chain reaction post intervention), 2 for antibiotic use. Six subjects were excluded for B lactis positive stool, either at baseline or in the Control or No-Intervention group after the intervention phase. There were no group differences in age, mood scores, gastrointestinal symptoms (detailed in the Supplementary Material), or salivary estrogen and progesterone.

FMPP Reduces the Reactivity of a Widely Distributed Network of Brain Regions to an Emotional Attention Task

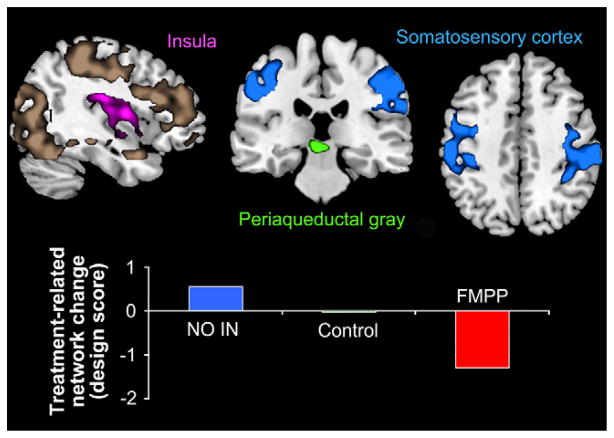

A widely distributed network of regions showed significant (49% cross-block covariance; P < .004) differential pre to post-intervention function across the 3 groups. The network included primary interoceptive and somatosensory regions, and a cluster in the midbrain region centered on the periaqueductal gray (PAG). Other network regions included the prefrontal cortex, precuneus, basal ganglia, and the parahippocampal gyrus (Figure 1 and the Results in the Supplementary Material and Supplementary Table 2). The network showed increased activity over time in the No-Intervention group, no change in the Control group, and an FMPP-intake–associated decrease in activity (Figure 1). No regions identified in this network showed increased activity after FMPP intervention.

Figure 1.

A distributed network of brain regions showing decreases in the FMPP group during the emotional faces attention task is shown in the shaded regions. Three regions of interest selected from the network for study in the resting state are highlighted in pink (insula), green (periaqueductal gray), and blue (somatosensory regions). The change in network strength with intervention is depicted graphically.

Ingestion of FMPP Is Associated With Altered Reactivity of Interoceptive and Somatosensory Regions to an Emotional Attention Task

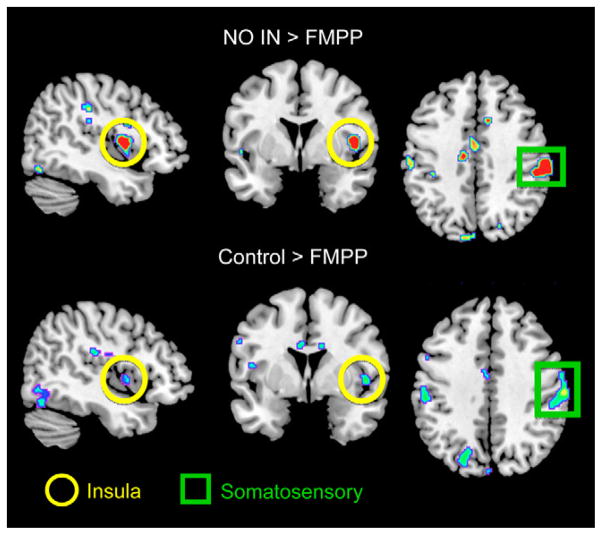

Supporting the findings from the connectivity analysis, region of interest, and whole-brain analyses identified FMPP-associated BOLD changes in the insular and somatosensory cortices (Figure 2). When pair-wise group differences in task response were assessed, the FMPP group showed a significant decrease in BOLD activity in the primary viscerosensory and somatosensory cortices (posterior and mid insula, see Supplementary Material) compared with Control and No-Intervention groups. Decreased FMPP-related BOLD activity in the amygdala was seen compared with No-Intervention. No regions showed increased BOLD activity in the FMPP group compared with either Control group, nor were there significant BOLD differences between the 2 Control groups. At the whole-brain level, FMPP significantly decreased BOLD activity in the mid insula cortex and primary somatosensory cortex compared with the No-Intervention group. These results are detailed in the Supplementary Material Results and Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 2.

Regions showing reduced activity in response to an emotional faces attention task after FMPP intervention are shown, with significant regions demarcated.

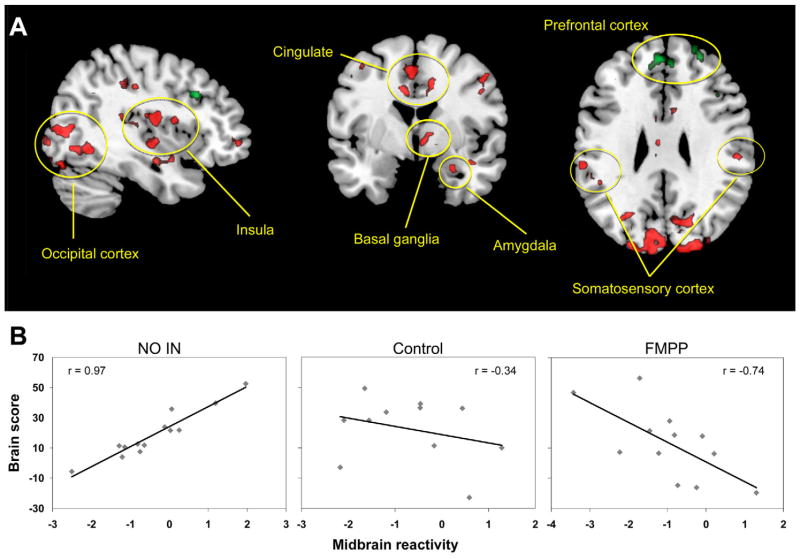

Ingestion of FMPP Is Associated With Alterations in a PAG-Seeded Resting-State Network

To investigate whether resting-state brain intrinsic connectivity was related to the FMPP-induced changes in reactivity to the emotional face attention task, we extracted task-related BOLD activity from the peak voxel of 3 key regions reported in the task PLS (insula, somatosensory cortex, and PAG) and used these values to “seed” a multivariate analysis of brain regions and their connectivity related to the task (“behavioral PLS” analysis). This analysis aimed to identify correlations between regional task-related brain activity and the resting-state functional connectivity data matrix. Of the 3 seed regions, only the PAG revealed an FMPP-related resting-state network, which was predictive of subsequent responses during the task. The PAG-seeded resting-state network accounted for 45.9% of the cross-block data covariance (P < .022) and is shown in Figure 3 and in the Supplementary Material Results and Supplementary Tables 4A and 4B. The network contained sensory regions (thalamus, insula, see Supplementary Material), limbic regions (cingulate gyrus, amygdala, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus), the basal ganglia, and attention-related regions (BA 40) consistent with previously reported PAG-connectivity findings in a large sample of healthy individuals.53 Although specific FMPP-associated resting-state networks were not identified using the insula and somatosensory cortex seeds, these regions were both significant nodes within the PAG-based network. The network correlated positively with task-induced PAG activity in the No-Intervention group, but was negatively correlated with task-induced PAG activity in the FMPP group. These regions had less prominent negative correlations with task-related PAG activity in the Control group. Conversely, the FMPP group showed positive correlation of task-induced PAG activity with cortical modulatory regions (medial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), and the No-Intervention group had negative correlation with these regions. The pattern of task activity correlation with the PAG resting network across groups is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A resting-state midbrain centered network has strong positive correlation with midbrain emotional reactivity after No-Intervention, is not engaged after Control, and is negatively correlated with midbrain activity after FMPP. This suggests a shift away from an arousal-based resting-state network and toward a regulatory network. Network regions are depicted in (A) (detailed in Supplementary Tables 4A and B). Red regions show areas that are positively correlated with midbrain activity in the No-Intervention group and negatively correlated in the FMPP group. Green regions are negatively correlated with midbrain activity in the No-Intervention group and are positively correlated in the FMPP group. (B) Correlation of the network with midbrain reactivity by group.

Symptom Reports and Safety

Detailed results are shown in the Supplementary Material Results. In summary: (1) baseline anxiety, depression, and gastrointestinal symptoms were low in all groups and showed no individual group differences; (2) no group-related changes were seen in any of the symptom reports; and (3) the study products were well tolerated.

Fecal Microbiota

Post-hoc analysis of fecal microbiota composition indicated a good randomization of the subjects at baseline. No significant change in microbiota composition vs baseline was found after intervention between groups.

Discussion

In healthy women, chronic ingestion of a fermented milk product with probiotic resulted in robust alterations in the response of a widely distributed brain network to a validated task probing attention to negative context. FMPP intervention-related changes during the task were widespread, involving activity reductions in brain regions belonging to a sensory brain network (primary interoceptive and somatosensory cortices, and precuneus), as well as frontal, prefrontal, and temporal cortices, parahippocampal gyrus, and the PAG. In addition, FMPP ingestion was associated with connectivity changes within a PAG centered resting-state network that included interoceptive, affective, and prefrontal regions. Based on reported findings in rodent studies, one might speculate that these changes are either induced by altered vagal afferent signaling to the NTS and connected brain regions via the PAG, or by systemic metabolic changes related to FMPP intake.36,54 These changes were not observed in a nonfermented milk product of identical taste, thus the findings appear to be related to the ingested bacteria strains and their effects on the host. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration in humans that chronic intake of a fermented milk product with probiotic can modulate brain activity.

In addition to their well-characterized local effects on the gut epithelium, gut immune function, and on the enteric nervous system, long-distance effects of the micro-biota on the liver, adipose tissue, and brain have been reported.1,2,35,39,55–58 Based on findings in preclinical models, integrity of the vagus nerve plays a role in some but not all brain effects, suggesting that some of the gut to brain signaling occurs via vagal afferent nerves and the wide range of brain regions receiving input from the NTS. Alternatively, several studies have demonstrated that the normal gut flora as well as the ingestion of probiotics can significantly alter blood metabolite levels related to amino acids and to polysaccharide metabolism.35,36 In a recent study using the identical probiotic consortium, no significant changes in the human gut microbiota composition after FMPP intervention were detected, but the intervention was associated with changes in the metatranscriptome, particularly in gene products related to plant polysaccharide metabolism.36 In healthy subjects harboring normal gut microbiota, it might be hypothesized that this FMPP impacts bacterial metabolic activities so metagenomics or metatranscriptome methods might be required to better understand its mechanisms of action.

In the current study, using a multivariate analysis we found a robust effect of a 4-week period of ingestion of FMPP on the evoked response of the brain to a task, which was confirmed in a region of interest and whole-brain analysis. Chronic FMPP ingestion was associated with reduced activity in the task-induced network, and this reduced task responsiveness was associated with an alteration in a resting-state network centered on the PAG. Intrinsic connectivity within a PAG-seeded resting-state network has been reported previously, involving both adjacent and distal brain regions (including insula and pre-genual cingulate cortex).53,59,60 In addition, resting-state connectivity between nodes of a PAG network has been found to predict pain responses to a nociceptive stimulus.61 The PAG receives interoceptive input, and is involved in integrated brain responses to nociceptive and emotional stimuli, including endogenous pain modulation and autonomic responses.62,63 It has been suggested that resting-state brain networks provide functional “templates” with which the brain can rapidly respond to changes in the environment. Therefore, differences in resting-state networks can predict brain responses to specific tasks.64 – 66 FMPP ingestion appeared to alter such a “template” in the case of the PAG-centered resting-state network, which correlated differentially with task-induced PAG activity between groups. Specifically, while task-induced PAG activity was positively correlated with a broad group of sensory/affective regions in the No-Intervention state, FMPP intervention induced a shift toward negative PAG correlations with sensory/affective regions and positive correlations with cortical regulatory regions, which have been associated with the dampening of emotional and sensory responsiveness (medial and dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex). In the context of this study, the change in resting-state–task-activity correlations provides support for the concept that chronic ingestion of FMPP has altered tonic interactions of the PAG with a widely distributed brain network. The presence of resting-state PAG-prefrontal connectivity has been shown to be predictive of effective descending pain modulation in a chronic pain syndrome, suggesting a broader role for this circuitry involving pain vulnerability.67

Although this study clearly demonstrates an effect of FMPP ingestion on evoked brain responses and resting-state networks in women, it was not designed to address the mechanisms mediating this effect. There are multiple peripheral mechanisms by which luminal micro-organisms can signal to the host, including but not limited to communication with 5-hydroxytryptamine– containing enterochromaffin cells in the gut epithelium and modulation of gut-associated immune cells.12 Paracrine signals from these epithelial cells to closely adjacent vagal afferents could result in vagal activation and signaling to the NTS. Alternatively, probiotic-induced changes in short-chain fatty acid production by the gut flora could activate acid-sensing receptors in the colon locally in epithelial cells or within enteric neurons, or distally in the portal vein.68,69 Other potential mediators of the observed probiotic effect include signaling molecules, which are produced by microbiota, including tryptophan metabolites, γ-aminobutyric acid, and other neuroactive substances.12,33 Although no significant differences were seen in the regional comparison between the Control and No-Intervention groups, the network analyses suggest that an intermediate effect might have occurred in the Control group (Figures 1 and 3). While the presence of a placebo effect underlying the observed changes in the Control group cannot be ruled out, the involved brain regions are not those typically observed in placebo studies, and the subjects reported no subjective changes in mood or gastrointestinal symptoms.70 Another explanation would be that the contents of the nonfermented dairy product also modulated the intestinal milieu in a way that led to altered gut– brain interactions.

In summary, our data demonstrate that chronic ingestion of a fermented milk product with probiotic containing a consortium of 5 strains, including B lactis CNCM I-2494, can modulate the responsiveness of an extensive brain network in healthy women. This is consistent with recent rodent studies showing a modulatory effect of probiotic intake on a wide range of brain regions in adult animals.1 Even though a possible relationship between the gut microbiota profile and mood has been postulated based on preclinical data, and a recent report in IBS patients provides further support for such a hypothesis, this study is the first to demonstrate an effect of FMPP intake on gut– brain communication in humans.17 As a proof of concept it has been successful in showing that such communication exists and is modifiable, even in healthy women. Further examination of these pathways in humans will elucidate whether such microbiota to brain signaling plays a homologous role in modulating pain sensitivity, stress responsiveness, mood, or anxiety, as reported previously in rodent models. In addition, identification of the signaling pathways between the microbiota and the brain in humans is needed to solidify our understanding of microbiota gut– brain interactions. If confirmed, modulation of the gut flora can provide novel targets for the treatment of patients with abnormal pain and stress responses associated with gut dysbiosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Joshua Bueller, Brandall Suyenobu, Cathy Liu, and Teresa Olivas for technical and administrative assistance.

Funding

This study was supported by Danone Research.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- BOLD

blood oxygenation level–dependent

- FMPP

fermented milk product with probiotic

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- ME

match emotions

- MF

match forms

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarius

- PAG

periaqueductal gray

Footnotes

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at http://dx.doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043.

Conflicts of interest

These authors disclose the following: Kirsten Tillisch received grant funding for this project from Danone Research. Denis Guyonnet, Sophie Legrain-Raspaud, and Beatrice Trotin are employed by Danone Research. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. PNAS. 2011;108:16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neufeld KM, Kang N, Bienenstock J, et al. Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:255–264. e119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messaoudi M, Lalonde R, Violle N, et al. Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:755–764. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heijtz RD, Wang S, Anuar F, et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. PNAS. 2011;108:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudo N, Chida Y, Aiba Y, et al. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol. 2004;558:263–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amaral FA, Sachs D, Costa VV, et al. Commensal microbiota is fundamental for the development of inflammatory pain. PNAS. 2008;105:2193–2197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711891105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bercik P, Denou E, Collins J, et al. The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:599–609. 609e1–e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rousseaux C, Thuru X, Gelot A, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates intestinal pain and induces opioid and cannabinoid receptors. Nat Med. 2007;13:35–37. doi: 10.1038/nm1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdu EF, Bercik P, Verma-Gandhu M, et al. Specific probiotic therapy attenuates antibiotic induced visceral hypersensitivity in mice. Gut. 2006;55:182–190. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.066100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins S, Verdu E, Denou E, et al. The role of pathogenic microbes and commensal bacteria in irritable bowel syndrome. Digest Dis. 2009;27(Suppl 1):85–89. doi: 10.1159/000268126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Salonen A, Nikkila J, et al. Intestinal micro-biota in healthy adults: temporal analysis reveals individual and common core and relation to intestinal symptoms. PloS One. 2011;6:e23035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA. Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:306–314. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer EA. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:453–466. doi: 10.1038/nrn3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cryan JF, O’Mahony SM. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: from bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messaoudi M, Violle N, Bisson JF, et al. Beneficial psychological effects of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in healthy human volunteers. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:256–261. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.4.16108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao AV, Bested AC, Beaulne TM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of a probiotic in emotional symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome. Gut Pathogens. 2009;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffery IB, O’Toole PW, Ohman L, et al. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut. 2012;61:997–1006. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas CM, Hong T, van Pijkeren JP, et al. Histamine derived from probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri suppresses TNF via modulation of PKA and ERK signaling. PloS One. 2012;7:e31951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preidis GA, Saulnier DM, Blutt SE, et al. Probiotics stimulate enterocyte migration and microbial diversity in the neonatal mouse intestine. FASEB J. 2012;26:1960–1969. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agostini S, Goubern M, Tondereau V, et al. A marketed fermented dairy product containing Bifidobacterium lactis CNCM I-2494 suppresses gut hypersensitivity and colonic barrier disruption induced by acute stress in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:376–e172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai C, Guandalini S, Zhao DH, et al. Antinociceptive effect of VSL#3 on visceral hypersensitivity in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome: a possible action through nitric oxide pathway and enhance barrier function. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;362:43–53. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson AC, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, McRorie J. Effects of Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 on post-inflammatory visceral hypersensitivity in the rat. Digest Dis Sci. 2011;56:3179–3186. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1730-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eutamene H, Lamine F, Chabo C, et al. Synergy between Lacto-bacillus paracasei and its bacterial products to counteract stress-induced gut permeability and sensitivity increase in rats. J Nutr. 2007;137:1901–1907. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.8.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyonnet D, Woodcock A, Stefani B, et al. Fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 improved self-reported digestive comfort amongst a general population of adults. A randomized, open-label, controlled, pilot study. J Digest Dis. 2009;10:61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whorwell PJ, Altringer L, Morel J, et al. Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1581–1590. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKernan DP, Fitzgerald P, Dinan TG, et al. The probiotic Bifido-bacterium infantis 35624 displays visceral antinociceptive effects in the rat. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1029–1035. e268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waller PA, Gopal PK, Leyer GJ, et al. Dose-response effect of Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 on whole gut transit time and functional gastrointestinal symptoms in adults. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1057–1064. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.584895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bannister K, Bee LA, Dickenson AH. Preclinical and early clinical investigations related to monoaminergic pain modulation. Neuro-therapeutics. 2009;6:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ossipov MH, Dussor GO, Porreca F. Central modulation of pain. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3779–3787. doi: 10.1172/JCI43766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilder-Smith CH. The balancing act: endogenous modulation of pain in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2011;60:1589–1599. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elsenbruch S. Abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome: a review of putative psychological, neural and neuro-immune mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staud R. Abnormal pain modulation in patients with spatially distributed chronic pain: fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2009;35:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raybould HE. Gut chemosensing: interactions between gut endocrine cells and visceral afferents. Auton Neurosci. 2010;153:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNulty NP, Yatsunenko T, Hsiao A, et al. The impact of a consortium of fermented milk strains on the gut microbiome of gnotobiotic mice and monozygotic twins. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:106ra106. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goehler LE, Lyte M, Gaykema RP. Infection-induced viscerosensory signals from the gut enhance anxiety: implications for psychoneuroimmunology. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:721–726. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bercik P, Park AJ, Sinclair D, et al. The anxiolytic effect of Bifido-bacterium longum NCC3001 involves vagal pathways for gut-brain communication. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ait-Belgnaoui A, Eutamene H, Houdeau E, et al. Lactobacillus farciminis treatment attenuates stress-induced overexpression of Fos protein in spinal and supraspinal sites after colorectal distension in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:567–573. e18–e19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayer EA. The neurobiology of stress and gastrointestinal disease. Gut. 2000;47:861–869. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.6.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnstone T, Somerville LH, Alexander AL, et al. Stability of amygdala BOLD response to fearful faces over multiple scan sessions. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Britton JC, Taylor SF, Sudheimer KD, et al. Facial expressions and complex IAPS pictures: common and differential networks. Neuroimage. 2006;31:906–919. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher PM, Hariri AR. Linking variability in brain chemistry and circuit function through multimodal human neuroimaging. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11:633–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rawlings NB, Norbury R, Cowen PJ, et al. A single dose of mirtazapine modulates neural responses to emotional faces in healthy people. Psychopharmacology. 2010;212:625–634. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1983-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guyonnet D, Schlumberger A, Mhamdi L, et al. Fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 improves gastrointestinal well-being and digestive symptoms in women reporting minor digestive symptoms: a randomised, double-blind, parallel, controlled study. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1654–1662. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509990882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agrawal A, Houghton LA, Morris J, et al. Clinical trial: the effects of a fermented milk product containing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 on abdominal distension and gastrointestinal transit in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:104–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manuck SB, Brown SM, Forbes EE, et al. Temporal stability of individual differences in amygdala reactivity. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1613–1614. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI, Crockett MJ, et al. Putting feelings into words: affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tottenham N, Tanaka JW, Leon AC, et al. The NimStim set of facial expressions: judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labus JS, Naliboff BN, Fallon J, et al. Sex differences in brain activity during aversive visceral stimulation and its expectation in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a network analysis. Neuroimage. 2008;41:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McIntosh AR, Lobaugh NJ. Partial least squares analysis of neuroimaging data: applications and advances. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S250–S263. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kong J, Tu PC, Zyloney C, et al. Intrinsic functional connectivity of the periaqueductal gray, a resting fMRI study. Behav Brain Res. 2010;211:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sawchenko PE. Central connections of the sensory and motor nuclei of the vagus nerve. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1983;9:13–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(83)90129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wells JM, Rossi O, Meijerink M, et al. Epithelial crosstalk at the microbiota-mucosal interface. PNAS. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4607–4614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000092107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mestdagh R, Dumas ME, Rezzi S, et al. Gut microbiota modulate the metabolism of brown adipose tissue in mice. J Prot Res. 2012;11:620–630. doi: 10.1021/pr200938v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seki E, Schnabl B. Role of innate immunity and the microbiota in liver fibrosis: crosstalk between the liver and gut. J Physiol. 2012;590:447–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.219691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Linnman C, Moulton EA, Barmettler G, et al. Neuroimaging of the periaqueductal gray: state of the field. Neuroimage. 2012;60:505–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Linnman C, Beucke JC, Jensen KB, et al. Sex similarities and differences in pain-related periaqueductal gray connectivity. Pain. 2012;153:444–454. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ploner M, Lee MC, Wiech K, et al. Prestimulus functional connectivity determines pain perception in humans. PNAS. 2010;107:355–360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906186106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bandler R, Shipley MT. Columnar organization in the midbrain periaqueductal gray: modules for emotional expression? Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:379–389. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keay KA, Clement CI, Owler B, et al. Convergence of deep somatic and visceral nociceptive information onto a discrete ventrolateral midbrain periaqueductal gray region. Neuroscience. 1994;61:727–732. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raichle ME, Gusnard DA. Intrinsic brain activity sets the stage for expression of motivated behavior. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:167–176. doi: 10.1002/cne.20752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Otti A, Guendel H, Laer L, et al. I know the pain you feel-how the human brain’s default mode predicts our resonance to another’s suffering. Neuroscience. 2010;169:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adelstein JS, Shehzad Z, Mennes M, et al. Personality is reflected in the brain’s intrinsic functional architecture. PloS One. 2011;6:e27633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mainero C, Boshyan J, Hadjikhani N. Altered functional magnetic resonance imaging resting-state connectivity in periaqueductal gray networks in migraine. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:838–845. doi: 10.1002/ana.22537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tazoe H, Otomo Y, Kaji I, et al. Roles of short-chain fatty acids receptors, GPR41 and GPR43 on colonic functions. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(Suppl 2):251–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Soret R, Chevalier J, De Coppet P, et al. Short-chain fatty acids regulate the enteric neurons and control gastrointestinal motility in rats. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1772–1782. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meissner K, Bingel U, Colloca L, et al. The placebo effect: advances from different methodological approaches. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16117–16124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4099-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.