Abstract

Objectives

Vapreotide, a synthetic analog of somatostatin, has analgesic activity most likely mediated through the blockade of neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R), the Substance P (SP) preferring receptor. The ability of vapreotide to interfere with other biological effects of SP has yet to be investigated.

Methods

We studied the ability of vapreotide to antagonize NK1R in three different cell types: immortalized U373MG human astrocytoma cells, human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), and a human embryonic kidney cell line, HEK293. Both U373MG and MDMs express endogenous NK1R while HEK293 cells, which normally do not express NK1R, are stably transformed to express human NK1R (HEK293-NK1R).

Results

Vapreotide attenuates SP-triggered intracellular calcium increases and NF-κB activation in a dose-dependent manner. Vapreotide also inhibits SP-induced IL-8 and MCP-1 production in HEK293-NK1R and U373MG cell lines. Vapreotide inhibits HIV-1 infection of human MDM in vitro, an effect that is reversible by SP pretreatment.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that vapreotide has NK1R antagonist activity and may have potential application as a therapeutic intervention in HIV-1 infection.

Keywords: Substance P (SP), Neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R), Somatostatin, Vapreotide, Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), SSTR2, CYN

Introduction

Substance P (SP) is a major peptide regulator of the interaction between the immune and nervous systems [1,2]. The biological response to SP is mediated by its preferred receptor, neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R). NK1R is a member of the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily (Gq/11) and has a typical structure of seven transmembrane domains, an extracellular N-terminus and an intracellular C-terminus [3]. Our previous investigations [4–11] have demonstrated the presence of NK1R at the both mRNA and protein levels in cells of the human immune system and the nervous system, including human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) [4], lymphocytes [5], microglia [6] and natural killer cells [11]. Subsequent to binding to NK1R, SP triggers the intracellular mobilization of calcium reserves [12–14], activation of nuclear factor-Kappa B (NF-κB) (a key transcriptional factor involved in the control of cytokine expression [15,16]), up-regulation of tissue factor expression [17] and up-regulation of IL-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) expression [15,18–21]. SP also induces immediate early gene (EGR-1 and c-FOS) expression [22–25]. We have observed that SP and NK1R are actively involved in HIV infection of human immune cells and, in particular, monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) [26,27]. SP enhances HIV replication in human peripheral MDM [28]. Interruption of the interaction between SP and NK1R with NK1R antagonists (CP-96,345 or aprepitant) inhibits HIV infection of human MDM [27,29].

Somatostatin is a peptide hormone which is distributed in many tissues including the immune system and the nervous system. Exposure to somatostatin causes inhibition of immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) secretion by B lymphocytes [30] and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion by T cells [31]. Vapreotide (RC-160) is a synthetic octapeptide analog of the naturally-occurring somatostatin hormone. It has analgesic activity, which is most likely mediated by NK1R, the SP preferring receptor [32]. Vapreotide displaces titrated SP (IC50 = 3.3+/− 1.8 × 10−7M) binding bronchial NK1R sites in a dose-dependent manner and it significantly and specifically reduces the SP-induced extravasations of the dye Evans Blue in the trachea and main bronchi via interaction with NK1R, suggesting that vapreotide also has an NK1R antagonist effect [32].

In order to further establish the NK1R antagonist effect of vapreotide in human cells, we investigated the effect of vapreotide on SP-induced elevation of cytosolic, free 2+Ca, activation of NF-κB, and downstream effects such as activation of immediate early genes and cytokine and chemokine production. We also examined the effect of vapreotide on HIV-1 replication in human MDM in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Cells and virus

HEK293, a human embryonic kidney cell line, and U373MG, a human astrocytoma cell line, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), glutamine, and antibiotics at 37°C in 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed one day before SP treatment. U373MG cells express endogenous NK1R [33]. The HEK293 cell line, which stably expresses human NK1R (HEK293-NK1R), was established as previous described [18].

Monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) were isolated from peripheral blood of normal adult donors (CFAR Immunology Core, University of Pennsylvania). The blood samples were identified as HIV-1 antibody negative by anonymous testing with the ELISA method (Coulter Immunology, Hialeah, FL). Monocytes were purified according to our previously described techniques [34,35] and cultured in 48-well plates at a density of 0.25 × 106cells/0.5 ml/well for 7–10 days before HIV-1 infection.

The M-tropic HIV-1 R5 strain Bal was obtained from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program.

Reagents

pNF-κB-luc multimer-driven Luciferase construct [36] was generously provided by Dr. Randy Q. Cron. The Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V was purchased from Amaxa (Gaithersburg MD). Luciferase assay system was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Substance P (SP) and vapreotide (RC-160) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). NK1R antagonist, CP-96,345 [37], was generously provided by Pfizer Inc. (Groton, CT). Aprepitant (Emend®), manufactured by Merck & Co. (Whitehouse Station, NJ), was purchased through the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Pharmacy and extracted and purified by chromatography. Cyanamid-154806 (CYN), a somatostatin 2 receptor (SSTR2) antagonist, was obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). EIA kits for MCP-1 and IL-8 were purchased from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). The sensitivity of the kits was < 5 pg/ml.

SP-Induced Calcium Mobilization

Intracellular calcium measurements were performed in fura-2 loaded cells using Tsien’s ratiometric method [38]. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. Fura-2 loading was performed by incubating cells for 45 minutes at room temperature in medium containing 4 μM fura 2-AM and 0.01% Pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were washed in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 1 mM calcium chloride and fluorescence was recorded in individual cells using an imaging system from Photon Technologies Inc. (Lawrenceville, NJ). Recordings were performed using excitation wavelengths of 340 nm (+2Ca bound Fura) and 380 nm (+2Ca unbound Fura) and emitted light was measured at 510 nm over 240 seconds. The ratio of these measurements (340/380) in combination with a standardization kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to calculate the intracellular calcium concentration. Peak intracellular calcium concentrations were determined after SP stimulation and were used to construct concentration-response curves. Logistic curves were fitted to data and used to derive EC50 values for substance P.

Luciferase Assay for NF-κB Activation

pNF-κB-luc plasmid (5 μg) was transfected into HEK293-NK1R (2 x106 cells per transfection) by Nucleofector II using the Cell Line Nucleofection Kit V following the manufacturer’s protocol. After transfection, the cells were cultured in 24-well plates (0.25 × 106 cells/well) in DMEM media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). 48 h post transfection, the cells were treated with SP (10−7M) in the presence or absence of NK1R antagonists (aprepitant or CP-96,345) (1 μM) or vapreotide (10 μM) for 6 h. Mock treated cells were used as controls. Cell-free lysates were collected in 0.25 ml of 1 X Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min. The cell-free lysates were used to determine the NF-kB-driven luciferase activity by the Luciferase assay system and a luminometer. The luciferase activity is expressed as relative light units (RLU). The results are presented as fold-change in RLU compared to untreated controls, which are defined as 1.0.

Vapreotide treatment

The HEK293-NK1R cells and U373MG cells were incubated with or without vapreotide for 10 minutes and then incubated with or without SP for 3 hours. In some experiments, cells were first incubated with CYN for 10 minutes, and then vapreotide was added and incubated for an additional 10 minutes, followed by stimulation with SP for 3 hours. Mock treated cells were used as controls.

HIV Infection

7–10 day-cultured MDM in 48-well plates (0.25 × 106 cells/well) were incubated with or without vapreotide for 2 h before infection with HIV-1. Cells were first incubated with vapreotide for 10 min and then SP was added to the MDM and the cells were incubated for the additional 2 h. Mock treated MDM served as controls. After a 2 h incubation with or without vapreotide and/or SP, the cells were infected overnight with cell-free HIV based on p24 antigen content (16 ng/106 cells), and then extensively washed to remove unbound virus. Fresh medium supplemented with vapreotide and/or SP was added as described above. The culture medium and the reagents were replaced twice weekly. At day 7 post HIV infection, cellular RNA was extracted from the MDM for assessment of HIV gag mRNA expression using real time RT-PCR assays.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time RT PCR Assays

Total RNA was extracted from U373MG, HEK293-NK1R and MDM cells using RNeasy kit (Qiagen), and the potential DNA contamination was eliminated by on-column DNase digestion as instructed by the manufacturer (Qiagen). RNA concentration was determined by Qubit fluorometer using Quant-iT RNA Assay kit (Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon).

Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using AffinityScript qPCR cDNA Synthesis kit (STRATAGENE, Cedar Creek, TX) with random primer as instructed by the manufacturer. Reverse transcriptase negative controls were used in order to control for genomic DNA contamination. 1 μl of the resulting cDNA was used as a template for real-time PCR amplification.

The sequences of the primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA).

Table 1.

Primers used for real-time PCR Assays

| Gene | Sequence of Primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| IL-8 | Sense: CTCTTGGCAGCCTTCCTGATTTCT Antisense: TGTGGTCCACTCTCAATCACTCTC |

| MCP-1 | Sense: CTCGCTCAGCCAGATGCAATCAAT Antisense: TGGAATCCTGAACCCACTTCTGCT |

| EGR-1 | Sense: GTGGCCTAGTGAGCATGACCAA Antisense: AAATGGGACTGCTGTCGTTGGATG |

| c-Fos | Sense: TGTCTGTGGCTTCCCTTGATCTGA Antisense: TGGATGATGCTGGGAACAGGAAGT |

| HIV gag [56] | Sense: CATGTTTTCAGCATTATCAGAAGGA Antisense: TGCTTGATGTCCCCCCACT Probe: CACCCCACAAGATTTAAACACCATGCTAA |

| GAPDH | Sense: GGTGGTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACA Antisense: GTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGTTGT |

The mRNA levels of IL-8, MCP-1, EGR-1, c-FOS, HIV gag and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were quantitatively determined using the iQ iCycler system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). Thermal cycling conditions were designed as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60° C for 1 min. The specificity of the amplification was confirmed by SYBR dye dissociation curve and agarose gel electrophoresis. All amplification reactions were performed in duplicate. The averages of the threshold cycle (Ct) values of the duplicates were used to calculate the relative mRNA levels of these genes. In order to control the integrity of the RNA and normalize mRNA levels in these samples GAPDH gene was used as previously described [39]. The magnitude of change in IL-8, MCP-1, c-Fos, and EGR-1 mRNA expression in response to SP and/or vapreotide or NK1R antagonists in the HEK293-NK1R or U373MG cells was calculated using the standard 2−(ΔΔCt) method [40]. For quantification of HIV gag cDNA in MDM, known amounts of HIV DNA isolated from ACH-2 cells were used to generate a standard curve. All standards and samples were run in duplicate.

Statistical analyses

The results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. for replicate observations. Evaluation of the significance of differences between parameters was performed using the Student’s t- test. In all cases, p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

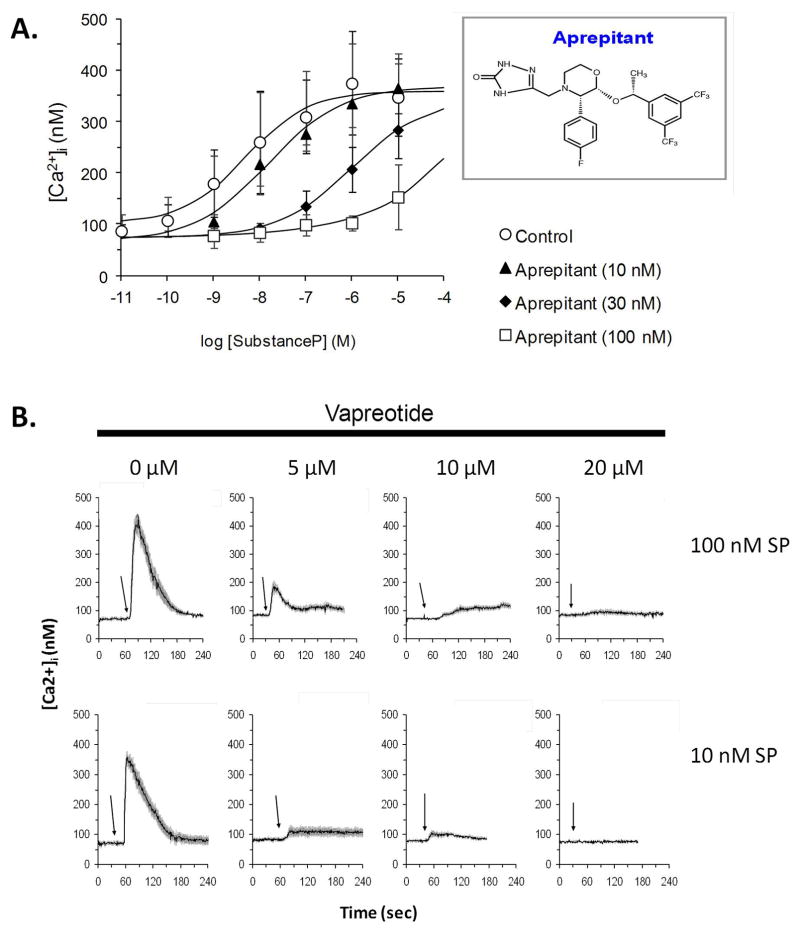

Vapreotide dose-dependently inhibits SP-induced intracellular calcium increases

SP induced an increase in calcium in U373MG cells in a dose-dependent manner with a maximum response at concentration of 0.1 μM, while the NK1R antagonist, aprepitant, completely antagonized this effect at 0.1 μM (Figure 1A). Vapreotide attenuated the effect of SP on calcium release in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1B). The concentration required for vapreotide to completely inhibit the effect of SP is about 100 times higher than that required for the NK1R antagonist aprepitant (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Aprepitant and vapreotide suppress SP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in U373MG cells.

A. The effect of different concentrations of aprepitant (10, 30 and 100 nM) on SP-induced intracellular calcium increase was measured in U373MG cells stimulated with concentrations of SP ranging from 10−11 to 10−5 M. Each data point represents the average calcium concentrations measured in eight individual cells ± SD.

B. U373MG cells were pretreated with different concentrations of vapreotide as indicated, followed by stimulation with 100 nM or 10 nM of SP. Representative tracings show the average intracellular calcium concentration for eight cells over 240 seconds of measurement.

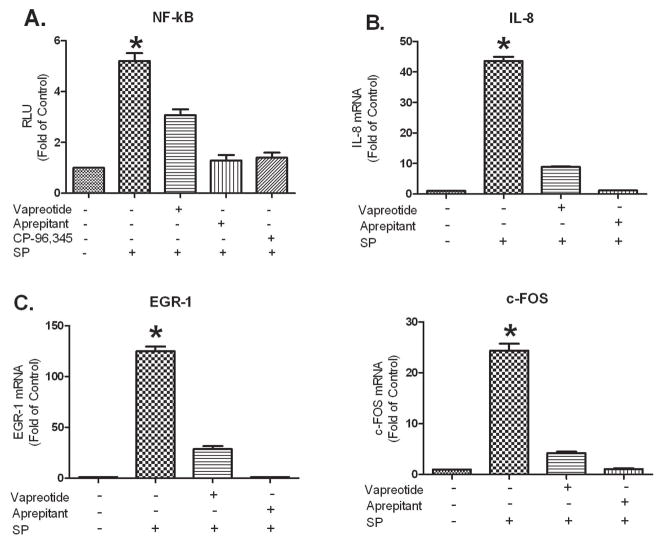

Vapreotide attenuates SP activation of NF-κB and inhibits SP-induced Gene Expression in HEK293-NK1R cells

SP increased NF-κB-driven-luciferase gene expression in HEK293-NK1R (Figure 2A) and this enhancement was antagonized by aprepitant or CP-96,345 and partially inhibited by vapreotide pretreatment.

Figure 2. Vapreotide attenuates SP-induced NF-κB activation and IL-8, EGR-1 and c-Fos mRNA up-regulation in HEK293-NK1R cells.

A. HEK293-NK1R cells that coexpress NF-κB-luc were pre-incubated with or without aprepitant (1 μM), CP-96,345 (1 μM), or vapreotide (10 μM) for 30 min followed by stimulation with SP (0.1 μM) for 6 h. Mock treated cells were used as controls. The results are presented as fold-change in Relative Light Units (RLU) compared to the mock treated control which is defined as 1.0.

B and C. HEK293-NK1R cells were pre-incubated with or without vapreotide (10 μM), aprepitant (1 μM), or mock treated as control for 30 min followed by 0.1 μM SP stimulation for 3 h. IL-8 (B), EGR-1 (C) and C-FOS (C) mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR and are presented as fold-change of mock treated control, which is defined as 1.0. These results are representative of three independent experiments ± S.D. NF-kB activation and IL-8, EGR-1 and c-Fos expression were significantly increased in SP treated cultures (* p<0.01) versus mock-treated control, aprepitant-treated, CP-96,345-treated or vapreotide-treated cultures by Student’s t-test.

SP treatment up-regulates the mRNA expression of IL-8, EGR-1 and c-FOS genes in HEK293-NK1R cells. The NK1R antagonist, aprepitant, inhibited these effects (Figure 2B and C). Vapreotide pretreatment also reduced SP-mediated increases in IL-8, EGR-1 and c-FOS expression.

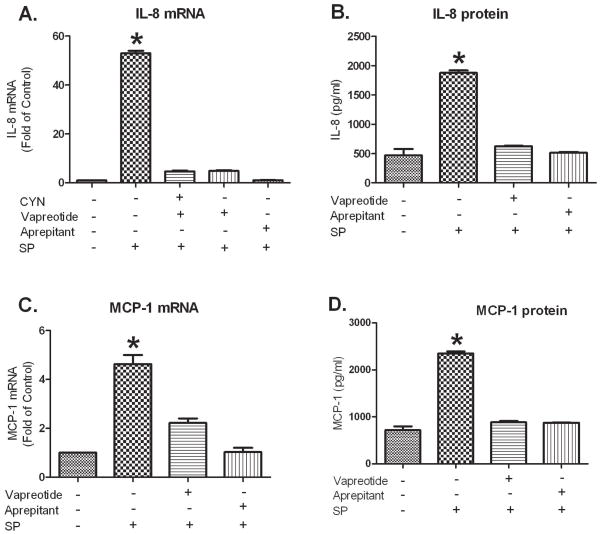

Vapreotide inhibits SP-induced cytokine and chemokine expression in U373MG cells

In order to further establish the NK1R antagonist effect of vapreotide, we examined its effect in U373MG cells that express endogenous NK1R. SP induced IL-8 expression at both mRNA and protein levels while both vapreotide and aprepitant inhibited this SP-induced IL-8 up-regulation (Figure 3A and B). Similarly, SP enhanced MCP-1 secretion while both vapreotide and aprepitant antagonized this up-regulation (Figure 3C and D). The effect of vapreotide on cell proliferation is mediated primarily by SSTR2 [41]. In order to further establish the NK1R antagonist effect of vapreotide, U373MG cells were pretreated with SSTR2 selective antagonist CYN followed by incubation with vapreotide and SP stimulation. The data (Figure 3A) show that pretreatment with CYN did not reverse the inhibitory effect of vapreotide on SP-stimulated IL-8 mRNA expression, suggesting that inhibition by vapreotide was not mediated by SSTR2.

Figure 3. Vapreotide inhibits SP-induced IL-8 and MCP-1 expression in U373MG cells.

A. and B. U373MG cells were treated with SP alone; vapreotide and SP; SSTR2 inhibitor CYN, vapreotide and SP; or aprepitant and SP. U373MG cells were pretreated with vapreotide (10 μM) or aprepitant (1 μM) for 30 min followed by incubation in the presence or absence of SP (0.1 μM) for 3 hours. When cells were treated with both CYN and vapreotide, the cells were first incubated with CYN (10 μM) for 30 min followed by vapreotide (10 μM) for additional 30 min, and then stimulated with SP (0.1 μM) for 3 hours. IL-8 mRNA (A) levels were determined by real-time PCR and are presented as fold-change of mock treated control, which is defined as 1.0. Secreted IL-8 (B) in culture medium was measured by EIA and the levels are presented as pg/ml.

C. and D. U373MG cells were pre-incubated with or without vapreotide (10 μM), aprepitant (1 μM), or mock treated as controls for 30 min followed by 0.1 μM SP stimulation for 3 h for when measuring MCP-1 mRNA (C) or 18 h when measuring MCP-1 secretion in the culture supernatants (D). MCP-1 mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR and are presented as fold of mock-treated control, which is defined as 1.0. Secreted MCP-1 in culture medium was measured by EIA and data are presented as pg/ml.

These results are representative of three independent experiments ± S.D. SP treated cultures had significantly higher levels of IL-8 and MCP-1 (*p<0.01) compared to mock-treated control, aprepitant-treated, and CYN and vapreotide-treated cultures by Student’s t-test.

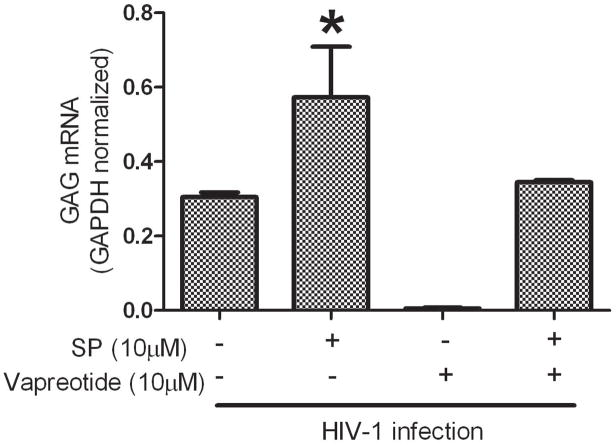

Vapreotide Inhibits HIV-1 Infection of MDM In Vitro

Vapreotide reduced HIV-1 replication in MDM as indicated by limited HIV gag mRNA expression compared to control MDM (Figure 4). In addition, SP treatment (10 μM) reversed vapreotide inhibition of HIV-1 replication in MDM (Figure 4). This observation indicates that the inhibition of HIV-1 replication by vapreotide is most likely due to its interaction with NK1R.

Figure 4. SP reverses vapreotide inhibition of HIV-1 replication in human MDM.

7–10 day cultured MDM were pretreated with SP and/or vapreotide at the concentrations indicated for 2 hours followed by infection with HIV-1 for 7 days. HIV gag mRNA levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR as copy numbers and normalized based on GAPDH levels. Representative data from one of three independent experiments ± S.D. are shown. GAG mRNA levels were significantly higher in SP treated cultures (* p<0.01) compared to mock treated control, vapreotide-treated or both vapreotide and SP-treated cultures by Student’s t-test.

Discussion

We studied the ability of vapreotide to antagonize NK1R in three different cell types: immortalized U373MG human astrocytoma cells, human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), and a human embryonic kidney cell line, HEK293. Both U373MG and MDMs express endogenous NK1R while HEK293 cells, which normally do not express NK1R, are stably transformed to express human NK1R (HEK293-NK1R). Previously, we showed a variety of biological effects in these three cell types, which express NK1R and respond to SP treatment [33,42–45]. In contrast, the HEK293 cell line lacking NK1R does not respond to SP treatment [42]. Vapreotide treatment antagonized SP-triggered intracellular calcium increases in a dose-dependent manner and reduced SP-induced NF-κB activation of IL-8 expression in the HEK293-NK1R cell line. It also inhibited SP-induced IL-8 and MCP-1 production in U373MG astrocytoma cells, which express endogenous NK1R indicating that vapreotide has NK1R antagonist activity. Furthermore, vapreotide attenuated HIV-1 replication in human MDM in vitro via interaction with NK1R.

Three downstream indicators of NK1R activation; SP-induced intracellular calcium increases, activation of NF-κB, and up-regulation of cytokine expression are antagonized by treatment with the NK1R antagonists CP-96,345 and aprepitant [14,33,43]. Vapreotide also reduced SP-induced calcium increases in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A and B). The concentration required for vapreotide to inhibit SP-induced calcium increase (10 μM) is about 100 times higher than that for aprepitant (100 nM) (Figure 1). In agreement with this observed difference, vapreotide displaced [3H]SP with an IC50 of 3.3 ± 1.8 × 10−7M on guinea-pig bronchi [32], which is also about 100 times higher than that obtained with a NK1R antagonist, CP96,345 (3.4 ± 0.8 × 10−9M) [37]. Thus, this difference is most likely due to the weaker binding affinity of vapreotide to NK1R in comparison to the non-peptide NK1R antagonists aprepitant and CP-96,345.

SP activation of NK1R results in activation of NF-κB in many cell systems, which, in turn, up-regulates IL-8 expression [18,19]. Thus, IL-8 expression is linked with NF-κB activation. We previously demonstrated that both NK1R antagonists and NK1R siRNA inhibit SP-induced up-regulation of IL-8 in the HEK293-NK1R cell line [18]. In the present study, our data show that vapreotide displayed an NK1R antagonist effect by reducing SP-induced NF-κB activation and increased IL-8 and MCP-1 expression in both the HEK293-NK1R cell line and U373MG cells. Furthermore, the effect of vapreotide was not due to its binding to SSTR2, the dominant somatostatin receptor subtype expressed on inflammatory cells [46], because pretreatment of cells with a selective SSTR2 antagonist CYN [47], did not reverse vapreotide inhibition of SP-mediated up-regulation of IL-8 expression (Figure 2).

SP–NK1R interaction has a modulatory effect on HIV infection [11,27,28,48–51]. Plasma SP levels are elevated in HIV-infected men and women [52,53]. We previously demonstrated that interruption of the interaction between SP and NK1R by NK1R antagonists (CP-96,345 or aprepitant) inhibits HIV-1 replication in MDM and decreases CCR5 expression [27,29,54]. Our data demonstrates that SP stimulates the expression of the pro-inflammatory chemokine MCP-1 in cells of astrocyte lineage, which may have a direct effect on HIV infection. MCP-1 contributes to HIV replication and disease progression including neuro-AIDS (as reviewed in [55]). Vapreotide reduced the pro-inflammatory response to SP, including MCP-1 expression, and inhibited HIV-1 replication in human MDM in vitro. We thus hypothesize that vapreotide, similar to other NK1R antagonists, may also interfere with the SP signaling via its interaction with NK1R, leading to the inhibition of HIV-1 infection.

Taken together, our data demonstrate that vapreotide has an NK1R antagonist effect and that it inhibits HIV-1 replication in human MDM in vitro via interaction with NK1R. This finding may have potential application for therapeutic intervention in HIV-1 infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 MH049981, P01 MH076388, and 1U01 MH090325 (SDD). We thank Dr. Christa Heyward for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations used

- SP

substance P

- NK1R

neurokinin-1 receptor

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- MDM

monocyte-derived macrophages

References

- 1.Tuluc F, Lai JP, Kilpatrick LE, Evans DL, Douglas SD. Neurokinin 1 receptor isoforms and the control of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douglas SD, Leeman SE. Neurokinin-1 receptor: Functional significance in the immune system in reference to selected infections and inflammation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1217:83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong TM, Anderson SA, Yu H, Huang RR, Strader CD. Differential activation of intracellular effector by two isoforms of human neurokinin-1 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho WZ, Lai JP, Zhu XH, Uvaydova M, Douglas SD. Human monocytes and macrophages express substance p and neurokinin-1 receptor. J Immunol. 1997;159:5654–5660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai JP, Douglas SD, Ho WZ. Human lymphocytes express substance p and its receptor. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;86:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai JP, Zhan GX, Campbell DE, Douglas SD, Ho WZ. Detection of substance p and its receptor in human fetal microglia. Neuroscience. 2000;101:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Douglas SD, Ho W. Human stem cells express substance p gene and its receptor. Journal of Hematotherapy and Stem Cell Research. 2000;9:445–452. doi: 10.1089/152581600419107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Douglas SD, Pleasure DE, Lai J, Guo C, Bannerman P, Williams M, Ho W. Human neuronal cells (nt2-n) express functional substance p and neurokinin-1 receptor coupled to mip-1 beta expression. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:559–566. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho WZ, Lai JP, Li Y, Douglas SD. Hiv enhances substance p expression in human immune cells. Faseb J. 2002;16:616–618. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0655fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho WZ, Douglas SD. Substance p and neurokinin-1 receptor modulation of hiv. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monaco-Shawver L, Schwartz L, Tuluc F, Guo CJ, Lai JP, Gunnam SM, Kilpatrick LE, Banerjee PP, Douglas SD, Orange JS. Substance p inhibits natural killer cell cytotoxicity through the neurokinin-1 receptor. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2011;89:113–125. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0410200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudduth-Klinger J, Schumann M, Gardner P, Payan DG. Functional and immunological responses of jurkat lymphocytes transfected with the substance p receptor. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1992;12:379–395. doi: 10.1007/BF00711540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seabrook GR, Fong TM. Thapsigargin blocks the mobilisation of intracellular calcium caused by activation of human nk1 (long) receptors expressed in chinese hamster ovary cells. Neurosci Lett. 1993;152:9–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90470-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai JP, Cnaan A, Zhao H, Douglas SD. Detection of full-length and truncated neurokinin-1 receptor mrna expression in human brain regions. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;168:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lieb K, Fiebich BL, Berger M, Bauer J, Schulze-Osthoff K. The neuropeptide substance p activates transcription factor nf-kappa b and kappa b-dependent gene expression in human astrocytoma cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:4952–4958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marriott I, Bost KL. Il-4 and ifn-gamma up-regulate substance p receptor expression in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;165:182–191. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan MM, Douglas SD, Benton TD. Substance p-neurokinin-1 receptor interaction upregulates monocyte tissue factor. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2012;242:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai JP, Lai S, Tuluc F, Tansky MF, Kilpatrick LE, Leeman SE, Douglas SD. Differences in the length of the carboxyl terminus mediate functional properties of neurokinin-1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12605–12610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806632105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koon HW, Zhao D, Zhan Y, Simeonidis S, Moyer MP, Pothoulakis C. Substance p-stimulated interleukin-8 expression in human colonic epithelial cells involves protein kinase cdelta activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1393–1400. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramnath RD, Sun J, Bhatia M. Role of calcium in substance p-induced chemokine synthesis in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. British journal of pharmacology. 2008;154:1339–1348. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieb K, Schaller H, Bauer J, Berger M, Schulze-Osthoff K, Fiebich BL. Substance p and histamine induce interleukin-6 expression in human astrocytoma cells by a mechanism involving protein kinase c and nuclear factor-il-6. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;70:1577–1583. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Sarraj A, Thiel G. Substance p induced biosynthesis of the zinc finger transcription factor egr-1 in human glioma cells requires activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00939-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo W, Sharif TR, Houghton PJ, Sharif M. Cgp 41251 and tamoxifen selectively inhibit mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and c-fos phosphoprotein induction by substance p in human astrocytoma cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:1225–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi SS, Lee HK, Shim EJ, Kwon MS, Seo YJ, Lee JY, Suh HW. Alterations of c-fos mrna expression in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and various brain regions induced by intrathecal single and repeated substance p administrations in mice. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:863–866. doi: 10.1007/BF02980180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitznagel H, Baulmann J, Blume A, Unger T, Culman J. C-fos expression in the rat brain in response to substance p and neurokinin b. Brain Res. 2001;916:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho WZ, Kaufman D, Uvaydova M, Douglas SD. Substance p augments interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha release by human cord blood monocytes and macrophages. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1996;71:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai JP, Ho WZ, Zhan GX, Yi Y, Collman RG, Douglas SD. Substance p antagonist (cp-96,345) inhibits hiv-1 replication in human mononuclear phagocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3970–3975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071052298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho WZ, Cnaan A, Li YH, Zhao H, Lee HR, Song L, Douglas SD. Substance p modulates human immunodeficiency virus replication in human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 1996;12:195–198. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Douglas SD, Lai JP, Tuluc F, Tebas P, Ho WZ. Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (aprepitant) inhibits drug-resistant hiv-1 infection of macrophages in vitro. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2007;2:42–48. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blum AM, Metwali A, Mathew RC, Elliott D, Weinstock JV. Substance p and somatostatin can modulate the amount of igg2a secreted in response to schistosome egg antigens in murine schistosomiasis mansoni. J Immunol. 1993;151:6994–7004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blum AM, Metwali A, Cook G, Mathew RC, Elliott D, Weinstock JV. Substance p modulates antigen-induced, ifn-gamma production in murine schistosomiasis mansoni. Journal of Immunology. 1993;151:225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betoin F, Advenier C, Fardin V, Wilcox G, Lavarenne J, Eschalier A. In vitro and in vivo evidence for a tachykinin nk1 receptor antagonist effect of vapreotide, an analgesic cyclic analog of somatostatin. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;279:241–249. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00168-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meshki J, Douglas SD, Hu M, Leeman SE, Tuluc F. Substance p induces rapid and transient membrane blebbing in u373mg cells in a p21-activated kinase-dependent manner. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hassan NF, Campbell DE, Douglas SD. Purification of human monocytes on gelatin-coated surfaces. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1986;95:273–276. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90415-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hassan NF, Cutilli JR, Douglas SD. Isolation of highly purified human blood monocytes for in vitro hiv-1 infection studies of monocyte/macrophages. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1990;130:283–285. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrak D, Memon SA, Birrer MJ, Ashwell JD, Zacharchuk CM. Dominant negative mutant of c-jun inhibits nf-at transcriptional activity and prevents il-2 gene transcription. Journal of Immunology. 1994;153:2046–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snider RM, Constantine JW, Lowe JA, 3rd, Longo KP, Lebel WS, Woody HA, Drozda SE, Desai MC, Vinick FJ, Spencer RW. A potent nonpeptide antagonist of the substance p (nk1) receptor. Science. 1991;251:435–437. doi: 10.1126/science.1703323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai JP, Yang JH, Douglas SD, Wang X, Riedel E, Ho WZ. Quantification of ccr5 mrna in human lymphocytes and macrophages by real-time reverse transcriptase pcr assay. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 2003;10:1123–1128. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.6.1123-1128.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pcr and the 2(-delta delta c(t)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buscail L, Esteve JP, Saint-Laurent N, Bertrand V, Reisine T, O’Carroll AM, Bell GI, Schally AV, Vaysse N, Susini C. Inhibition of cell proliferation by the somatostatin analogue rc-160 is mediated by somatostatin receptor subtypes sstr2 and sstr5 through different mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1580–1584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen P, Douglas SD, Meshki J, Tuluc F. Neurokinin 1 receptor mediates membrane blebbing and sheer stress-induced microparticle formation in hek293 cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meshki J, Douglas SD, Lai JP, Schwartz L, Kilpatrick LE, Tuluc F. Neurokinin 1 receptor mediates membrane blebbing in hek293 cells through a rho/rho-associated coiled-coil kinase-dependent mechanism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:9280–9289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808825200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Douglas SD, Lai JP, Tuluc F, Schwartz L, Kilpatrick LE. Neurokinin-1 receptor expression and function in human macrophages and brain: Perspective on the role in hiv neuropathogenesis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1144:90–96. doi: 10.1196/annals.1418.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chernova I, Lai JP, Li H, Schwartz L, Tuluc F, Korchak HM, Douglas SD, Kilpatrick LE. Substance p (sp) enhances ccl5-induced chemotaxis and intracellular signaling in human monocytes, which express the truncated neurokinin-1 receptor (nk1r) J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:154–164. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0408260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elliott DE, Li J, Blum AM, Metwali A, Patel YC, Weinstock JV. Sstr2a is the dominant somatostatin receptor subtype expressed by inflammatory cells, is widely expressed and directly regulates t cell ifn-gamma release. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2454–2463. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2454::AID-IMMU2454>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Booth CE, Kirkup AJ, Hicks GA, Humphrey PP, Grundy D. Somatostatin sst(2) receptor-mediated inhibition of mesenteric afferent nerves of the jejunum in the anesthetized rat. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:358–369. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Douglas SD, Song L, Sun S, Ho WZ. Substance p enhances hiv-1 replication in latently infected human immune cells. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2001;121:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00439-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo CJ, Lai JP, Luo HM, Douglas SD, Ho WZ. Substance p up-regulates macrophage inflammatory protein-1beta expression in human t lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;131:160–167. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00277-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manak MM, Moshkoff DA, Nguyen LT, Meshki J, Tebas P, Tuluc F, Douglas SD. Anti-hiv-1 activity of the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant and synergistic interactions with other antiretrovirals. AIDS (London, England) 2010;24:2789–2796. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283405c33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vinet-Oliphant H, Alvarez X, Buza E, Borda JT, Mohan M, Aye PP, Tuluc F, Douglas SD, Lackner AA. Neurokinin-1 receptor (nk1-r) expression in the brains of siv-infected rhesus macaques: Implications for substance p in nk1-r immune cell trafficking into the cns. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177:1286–1297. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Douglas SD, Cnaan A, Lynch KG, Benton T, Zhao H, Gettes DR, Evans DL. Elevated substance p levels in hiv-infected women in comparison to hiv-negative women. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2008;24:375–378. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Douglas SD, Ho WZ, Gettes DR, Cnaan A, Zhao H, Leserman J, Petitto JM, Golden RN, Evans DL. Elevated substance p levels in hiv-infected men. AIDS (London, England) 2001;15:2043–2045. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200110190-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Douglas SD, Song L, Wang YJ, Ho WZ. Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (aprepitant) suppresses hiv-1 infection of microglia/macrophages. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008;3:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s11481-008-9117-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ansari AW, Heiken H, Meyer-Olson D, Schmidt RE. Ccl2: A potential prognostic marker and target of anti-inflammatory strategy in hiv/aids pathogenesis. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3412–3418. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palmer S, Wiegand AP, Maldarelli F, Bazmi H, Mican JM, Polis M, Dewar RL, Planta A, Liu S, Metcalf JA, Mellors JW, Coffin JM. New real-time reverse transcriptase-initiated pcr assay with single-copy sensitivity for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 rna in plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4531–4536. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4531-4536.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]