Abstract

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection may initiate production of autoantibodies and development of cancer and autoimmune diseases. Here we outline phenotypic and functional changes in B cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) related to EBV infection. The B-cell phenotype was analysed in blood and bone marrow (BM) of RA patients who had EBV transcripts in BM (EBV+, n = 13) and in EBV− (n = 22) patients with RA. The functional effect of EBV was studied in the sorted CD25+ and CD25− peripheral B cells of RA patients (n = 18) and healthy controls (n = 9). Rituximab treatment results in enrichment of CD25+ B cells in peripheral blood (PB) of EBV+ RA patients. The CD25+ B-cell subset displayed a more mature phenotype accumulating IgG-expressing cells. It was also enriched with CD27+ and CD95+ cells in PB and BM. EBV stimulation of the sorted CD25+ B cells in vitro induced a polyclonal IgG and IgM secretion in RA patients, while CD25+ B cells of healthy subjects did not respond to EBV stimulation. CD25+ B cells were enriched in PB and synovial fluid of RA patients. EBV infection affects the B-cell phenotype in RA patients by increasing the CD25+ subset and by inducing their immunoglobulin production. These findings clearly link CD25+ B cells to the EBV-dependent sequence of reactions in the pathogenesis of RA.

Keywords: anti-CD20 treatment, bone marrow, CD25+ B cells, Epstein–Barr virus, rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

B cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).1,2 They function as antigen-presenting cells, which activate T cells and initiate auto-reactivity, and as a source of antibodies binding the Fc-portion of IgG (rheumatoid factor) and citrullinated peptides. Production of rheumatoid factor and citrullinated peptides is recognized as a sensitive predictor of the development of RA in healthy individuals and as a biomarker of severe joint-destructive diseases that lead to early disability.3,4 B-cell depletion therapy using anti-CD20 antibodies, rituximab (RTX), is a successful way to treat patients with RA. This treatment efficiently reduces the disease activity and 50–70% of patients with RA achieve good and moderate responses at 6-month follow up.5–7 A substantial number of patients with RA obtain a long relapse-free period after the initial treatment. A single course of treatment with RTX and re-treatment over 5 years is associated with improved efficacy and inhibition of progressive joint damage.7–10 The immunological effects of RTX are associated with a partial depletion of B cells acting via autolysis, or via cell-mediated cytotoxicity.11 The vast majority of RTX-treated patients have a complete depletion of the CD19+ B-cell population in the peripheral blood (PB), which lasts for 4–12 months after treatment.12 The B-cell populations sensitive to depletion with RTX are characterized by expression of IgD and IgM, known as antigen-naive and un-switched subtypes before they enter the germinal centre.13 The bone marrow (BM) preserves up to 30%13 and synovial tissue up to 60%14 of B cells 1 and 3 months after the RTX treatment. In addition to memory and plasma cells, the BM retains also immature and transitional B cells and early B-cell progenitors not expressing CD20.13 Serological consequences of RTX treatment may be followed by a rapid and reversible decrease of rheumatoid factor and citrullinated peptide antibody levels,15 whereas the total immunoglobulin level decreases gradually with repeated B-cell depletion.16,17

Despite the effective B-cell depletion and consequent decrease of autoantibody levels in nearly all treated patients, clinical response may be insufficient or short-lasting (less than 6 months) in a substantial proportion of RTX-treated patients. Efforts of several research groups have been combined to identify the clinical18–20 and molecular21–24 parameters that are associated with an insufficient clinical response to RTX treatment. Our group has recently found a positive association between the presence of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genome in the BM of patients with RA and clinical response to RTX treatment.25 Interestingly, RTX treatment was followed by complete clearance of EBV from the BM. The ability to respond to interferon stimulation, an essential mechanism of human anti-viral defence, may potentially predict clinical effect of RTX in patients with RA.26,27

Infection with EBV is one of the environmental risk factors for the development of RA.28 The EBV glycoprotein gp110 contains a sequence identical to the motif of the HLA-DRB1 alleles within the MHC II complex; called ‘shared epitope’, it is the strongest known genetic factor for the development of RA.29–31 Also, EBV infection in carriers of shared epitope greatly enhanced the development of RA.30 Consequently, a compromised innate immune response towards EBV and poor viral clearance are attributed to RA patients and lead to a high load of EBV-infected cells in the circulating blood and in the synovial cells, impaired cytolytic activity of T cells to EBV proteins and high titres of anti-EBV antibodies compared with healthy subjects.32–37 B cells are currently considered critical for the primary EBV infection and for its persistence. Epstein–Barr virus activates B cells and induces their proliferation and transformation into antibody-secreting cells.38 It has the ability to infect almost all types of B cells in vivo but naive IgM+ IgD+ B cells are the major target in tonsils, while the latent infection is found in the memory B-cell pool.39–41

The naive B-cell subset seems to be the cell population that shares susceptibility to RTX and EBV, so we attempted to outline phenotypic and functional changes in the peripheral blood and bone marrow B cells of patients with RA following RTX treatment and during EBV infection.

Materials and methods

Patients and sample collection

Samples of BM and PB were collected from 35 patients with established RA, diagnosed according to the ACR 1987 criteria42 before B-cell depletion therapy with anti-CD20 antibodies.13 All patients were recruited from the Rheumatology Clinic at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, Sweden, during the period from January 2007 to September 2008, and all patients gave written informed consent to participate. Additionally, 18 patients with RA donated PB samples for functional analysis. Another 10 patients with RA also donated PB and synovial fluids for phenotypic B-cell analysis. All patients with RA were receiving methotrexate treatment and had not been treated with RTX previously. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients and their immunosuppressive treatment are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and healthy controls

| Parameter | RA patients, EBV+ (n = 13) | RA patients, EBV– (n = 22) | RA patients, synovia (n = 10) | RA patients, functional (n = 18) | Healthy controls (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (range) | 61·1 (44–81) | 60·2 (33–82) | 61·4 (53–81) | 66·7 (54–87) | 63·5 (58–72) |

| Gender, f/m | 14/1 | 16/5 | 8/2 | 13/5 | 9/2 |

| Number of B cells × 109/l in peripheral blood | |||||

| Median ± SEM | 0·09 ± 0·04 | 0·13 ± 0·02 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Disease duration, mean years | 17·8 (6–35) | 15·6 (6–37) | 9 (0–20) | 15·6 (3–38) | 0 |

| Rheumatoid factor, positive | |||||

| At baseline | 13 (87%) | 19 (90%) | 5 (50%) | 17 (94%) | n.d. |

| At 6 months follow up | 9 (60%) | 6 (28%) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| DAS28 | |||||

| At baseline | 5·90 (4·8–6·8) | 5·8 (4·5–6·9) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| At 6 months follow up | 3·95 (2·2–5·9) | 4·3 (2·2–6·4) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Responder is defined as a change in DAS28 > 1·3 | 12 (80%) | 14 (61%) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug treatments | |||||

| Methotrexate | 14 (17 mg/w) | 19 (18 mg/w) | 6 (17 mg/w) | 17 (15 mg/w) | n.d. |

| Cyclosporin | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mycofenolate mofetil | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Leflunomide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chlorambucil | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Azathioprin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sulphasalazin | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| Cyclosporine A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Responder | 9 | 13 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Previous RTX treatment | 3 | 7 | |||

| Non-responder | 4 | 7 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Previous RTX treatment | 1 | 1 | |||

| Patients not treated with RTX | 2 | 1 | 10 | 18 | 11 |

DAS28, disease activity score; n.d., not done; RTX, rituximab.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Board in Gothenburg, Sweden (Dnr 633-07).

Blood and bone marrow samples

Heparinized samples of PB and BM aspirates (10 ml each) were collected, mononuclear leucocytes were separated and submitted to flow cytometric analyses and functional tests as described previously.13,43–45 The presence of EBV DNA was evaluated from the whole blood and BM aspirates using real-time PCR at the Virology Laboratory at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, as previously described.25 Detection of 10 EBV-DNA copies was sufficient to stratify a patient as EBV+.

Flow cytometry

The BM and PB cells were prepared and stained for the FACS analysis as previously described.43,44 To avoid non-specific binding, cells were pre-incubated with 0·1% rabbit serum for 15 min at room temperature, where after cells were stained with the following monoclonal antibodies used in different combinations: Peridinin Chlorophyll-conjugated anti-CD3 (SK7), eFluor450-conjugated anti-CD19 (HIB19), phycoerythrin-conjugated or FITC-conjugated anti-CD25 (2A3), phycoerythrin- or allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD27 (LI28), allophycocyanin-conjugated CD95 (DX2). All the antibodies were produced in mice and purchased from BD-Bioscience (BD-Bioscience, Erebodegem, Belgium) except for anti-CD19, which was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

For the immunoglobulin analyses we used FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-IgA (F0057), rabbit anti-IgD (F0059), rabbit anti-IgG (F0056) and rabbit anti-IgM (F0058) antibodies (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Polyclonal rabbit F(ab')2 anti-human immunoglobulin was used as isotype control.

Between 3 × 105 and 1·5 × 106 events were collected using a FACSCanto II equipped with FACS Diva software (BD-Bioscience). Cells were gated based on fluorochrome minus one setting when needed,46 and a representative gating strategy is shown in Fig. 2(f). A minimum of 50 cells per gate was used as an inclusion criterion. All analyses were performed using FlowJo software (Three Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

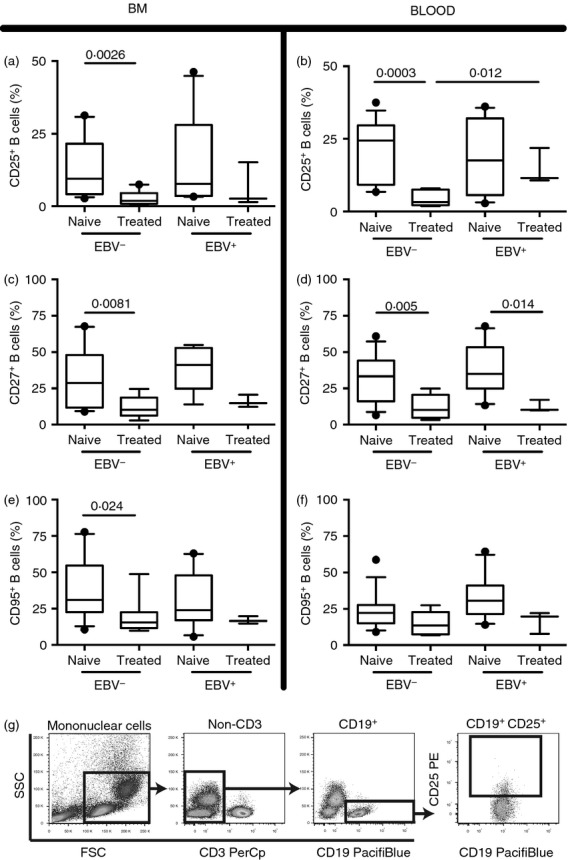

Figure 2.

Effects of rituximab (RTX) treatment on CD25, CD27 and CD95 B-cell populations with respect to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) status. Following gradient centrifugation 2 × 10e5 to 2 × 10e5 mononuclear cells isolated from peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) of EBV+ and EBV− patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were stained with CD19 in combination CD25 (a, b), CD27 (c, d) or CD95 (e, f) and analysed using flow cytometry. (g) A representative dot plot is presented showing the gating strategy. The RTX-naive group includes 10 EBV+ patients patients with RA and 13 who were EBV−. In the RTX-treated group three patients with RA were EBV+ whereas 10 were EBV−. Boxes and whiskers show 10–90 centiles and lines in boxes represent medians. Statistical evaluation was performed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney t-test and a P-value below or equal to 0·05 was considered significant.

Phenotype analysis of B-cell populations

B cells were defined as CD19+ CD3−. CD27 was used as a memory B-cell marker, alone or in combination with IgA, IgD, IgG and IgM. Combination of CD27 and IgD gave four different populations: IgD− CD27− (immature B cells), IgD+ CD27− (naive B cells), IgD+ CD27+ (unswitched memory B cells) and finally, IgD− CD27+ (switched memory B cells and plasmablasts).47,48

Cell sorting and stimulation

Mononuclear leucocytes of the PB were stained with Peridinin Chlorophyll-conjugated anti-CD3, eFluor450-conjugated CD19 and phycoerythrin-conjugated CD25 and sorted into CD19+ CD25+ and CD19+ CD25− populations using the FACS-Aria II (BD-Bioscience, San José, CA) as described previously.49 The purity of these sorted cells was > 97·5%. The viability of the cells was assessed using trypan blue. The sorted cell populations were stimulated for 96 hr with EBV-rich medium (3·6 × 106 copies/culture, kindly provided by the Immunology Laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, Sweden). After stimulation cells were counted using Bürker chambers and viability stained using trypan blue exclusion. The EBV-stimulated cells had a viability of 95%. These numbers were used to calculate the number of living cells added to the ELISPO assay below.

Analysis of antibody-secreting cells

The sorted CD25+ and CD25− B cells were subjected to ELISPOT analysis of isotype IgG, IgA and IgM in EBV-stimulated or unstimulated conditions, as described.50

Statistical analysis

For analysis between EBV+ and EBV− patients the Mann–Whitney U-test was used. Comparisons made between CD25+ and CD25− values from the same patient are analysed using the paired Student's t-test and the Mann–Whitney t-test. Differences of P < 0·05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

EBV load in the PB and in BM

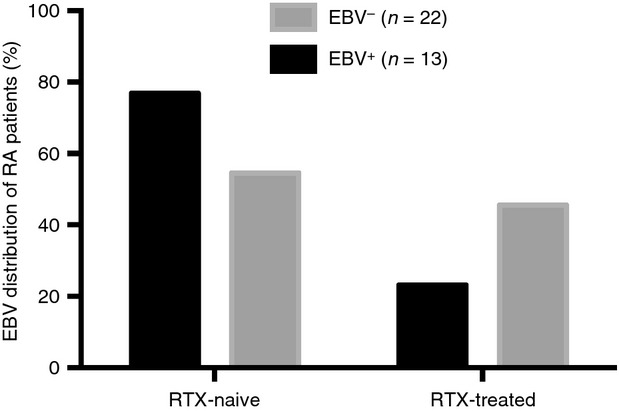

Patients with RA were stratified according to the presence of EBV transcripts in the BM into EBV+ (n = 13) with EBV load 1185 ± 830 copies/ml, and EBV− (n = 22). Among the EBV+ RA patients, six had concomitant EBV-DNA copies detected in the PB (500 ± 718 copies/ml). The remaining 22 patients had no detectable EBV-DNA in BM and PB. Ten of the EBV+ patients (77%) had not been treated with RTX previously (RTX-naive group), while the remaining three EBV+ patients comprised the RTX-treated group (Fig. 1). The RTX-naive group had similar EBV load in BM and PB to the RTX-treated patients with RA.

Figure 1.

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) load in the peripheral blood and in bone marrow. The EBV distribution of the included patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In the rituximab (RTX) -naive group 10 patients with RA were EBV+ and 13 EBV−. In the RTX-treated group three RA patients were EBV+ whereas 10 were EBV−.

No differences regarding absolute numbers of CD19+ B cells in peripheral blood could be detected between the EBV+ and EBV− groups (median 0·09 ± 0·04 × 109/l versus 0·13 ± 0·02 × 109/l) or between the RTX naive and RTX-treated groups (median 0·09 ± 0·03 × 109/l versus 0·12 ± 0·03 × 109/l). The average time span between RTX treatment and sample collection was 24 months. We have previously shown in Rehnberg et al.13 that there were no differences in absolute numbers of CD19+ B cells in BM between the RTX-naive and RTX-treated groups.

EBV effects on the CD25+ B-cell phenotype

The EBV infection is associated with an enrichment of CD25+, CD27+ and CD95+ cells in lymphocyte populations.51–53 The populations of CD25+, CD27+ and CD95+ B cells were significantly reduced in BM and PB of the RTX-treated RA patients (Fig. 2). This was consistently found in the EBV+ and EBV− patients. The CD25+ B-cell population remained larger in PB of the EBV+ RTX-treated patients (Fig. 2b).

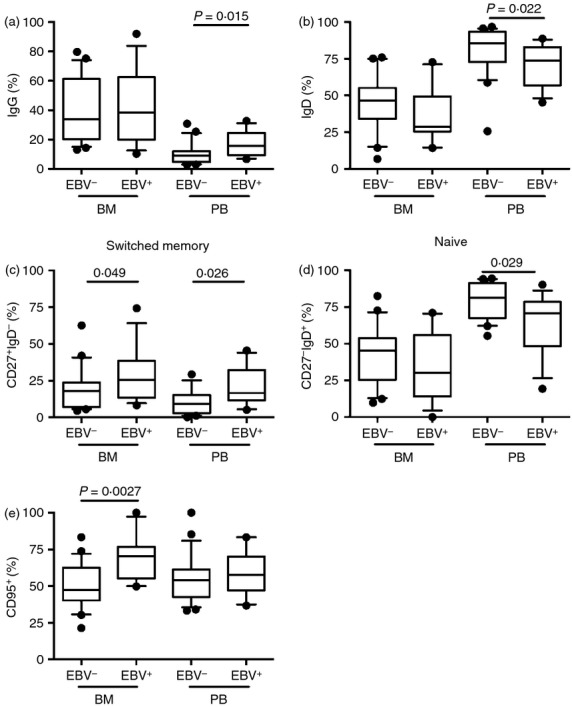

Comparison of CD25+ B-cell populations was performed in BM and PB of the EBV+ and EBV− patients. CD25+ population of EBV+ RA patients displayed an increased frequency of IgG (P = 0·015) and a decreased frequency of IgD (P = 0·022) in PB, suggesting a more mature phenotype (Fig. 3a,b). The higher maturation state was further supported by investigation of the CD27 IgD expression. The CD25+ population was enriched within the switched memory (CD27+ IgD−) B-cell populations in PB and in BM of EBV+ patients (Fig. 3c), whereas naive B cells (CD27−IgD+) were reduced in PB (Fig. 3d). Additionally, the EBV+ patients had a higher frequency of CD25+ CD95+ cells in BM (Fig. 3e).

Figure 3.

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) effects on the CD25+ B-cell phenotype. Following gradient centrifugation 2 × 10e5 to 2 × 10e5 mononuclear cells isolated from peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) of EBV+ and EBV− patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were analysed using flow cytometry. (a) The frequency of CD25+ IgG+, in (b) CD25+ IgD+, in (c) CD25+ CD27+ IgD− and in (d) CD25+ CD27+ IgD+ whereas in (e) the CD25+ CD95+ B cells are shown. In PB and BM there were 13 EBV+ patients with RAand 22 EBV– RA patients. Boxes and whiskers show 10–90 centiles and lines in boxes represent medians. Statistical evaluation was performed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney t-test and a P-value below or equal to 0·05 was considered significant.

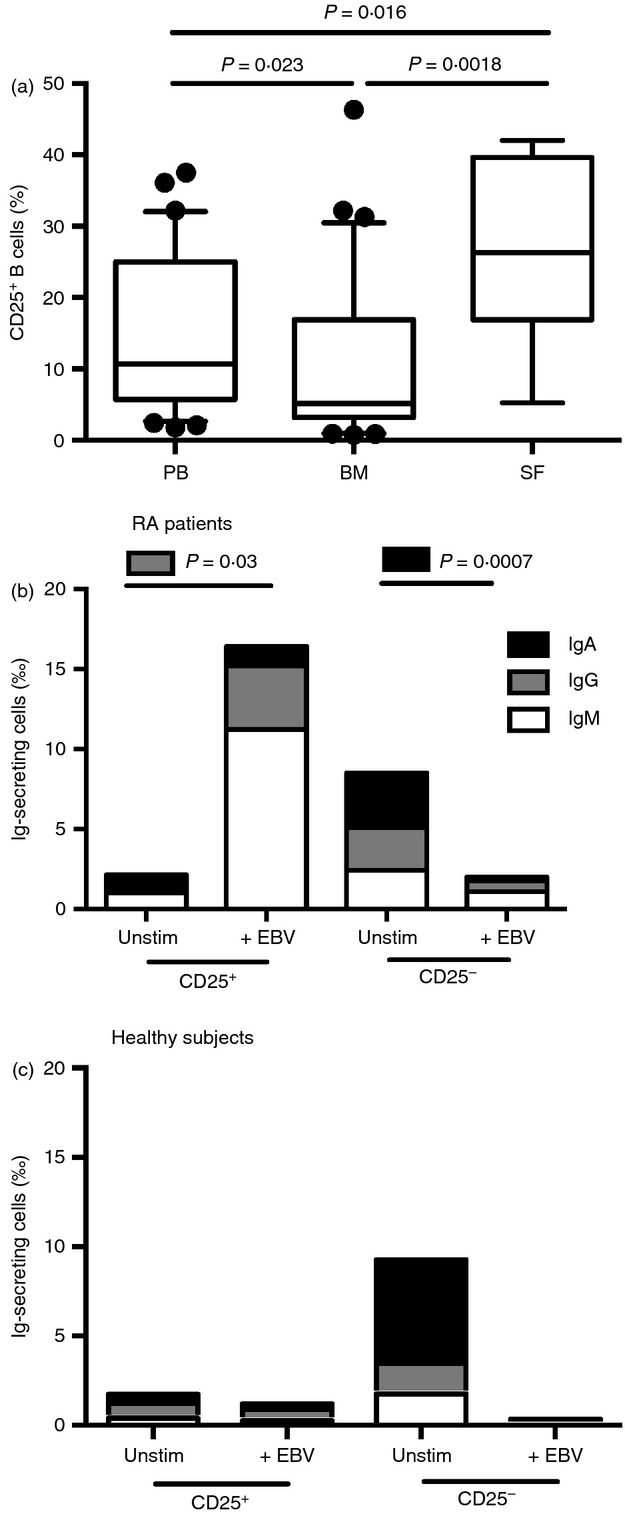

CD25+ B cells are enriched in PB and maintain immunoglobulin secretion following EBV stimulation

The frequency of CD25+ B cells in PB, BM and synovial fluid ofpatients with RA was assessed. The CD19+ CD25+ population was enriched in PB and in the inflamed synovial fluid compared with BM (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

CD25+ B cells are enriched in peripheral blood (PB) and synovial fluid SF, and maintain immunoglobulin secretion following Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) stimulation. Isolated cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were stained for CD19 and CD25 and analysed using flow cytometry. In (a) the frequency CD25+ B cells in PB, bone marrow (BM) and SF isolated from patients with RA were investigated. In PB and BM n = 35, and in SD n = 8. Moreover, B cells from patients with RA (b) and control subjects (c) were sorted into CD19+ CD25+ or CD19+ CD25− populations. The number of immunoglobulin-producing cells was counted in unstimulated conditions and after 96 hr of EBV stimulation using ELISPOT. Isotypes of IgM (white box), IgG (grey box) and IgA (black box) are shown, and bars represent the mean of each group. Ten patients with RA were unstimulated, of which seven were EBV-stimulated. Among healthy controls, 11 were unstimulated, of which two were EBV-stimulated. Statistical evaluation was performed using paired t-test. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparison between groups. P-values < 0·05 was considered significant.

Mononuclear cells in PB sorted into CD19+ CD25+ and CD19+ CD25− subsets were stimulated with EBV (3·6 × 106 copies/ culture). The CD25+ cultures responded to EBV stimulation with a significant increase in the number of immunoglobulin-producing cells, but no increase was observed in CD25– cultures of the same RA patient (Fig. 4b). The stimulatory effect was seen on the IgM- and IgG-producing CD25+ cells. Similar EBV stimulation of the CD25+ cultures from healthy subjects had no increase of immunoglobulin-producing cells (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

We have previously shown that RA patients with EBV replication in BM present a better clinical response to RTX treatment.25 Interestingly, RTX treatment was associated with a clear reduction of EBV load in patients with RA. These data allowed us to speculate that active EBV might be harboured within the RTX-sensitive B-cell populations in vivo. As a consequence, in the present study we assessed the impact of EBV infection on the phenotype and function of B cells in blood and BM of patients with RA.

The present study identifies the CD25+ subset of B cells to be enriched in PB of EBV+ RA patients suggesting that this population might be an important source of EBV infection for reactivation and re-infection of the RA patient. Importantly, EBV transfection has shown an induced CD25 expression in Hodgkin's lymphoma cells and in Burkitt's lymphoma cells51,53 and in natural killer cell lines.52 Similarly, EBV-specific T cells can be selected using CD25.54 In patients with RA, the CD25+ B-cell subset belongs to the memory pool of B cells, which is functionally characterized by an increased IL-10 secretion and low spontaneous immunoglobulin secretion.43–45 We found that the CD25+ B-cell population was enriched with the cells expressing the activation and apoptosis marker CD95. This is supported by our previous data where we observed that EBV replication gave rise to a concomitant expression of CD95 on CD19+ B cells and this might increase the sensitivity to RTX-induced depletion.25 On the other hand, it has been shown that cells from patients with RA may be resistant to CD95-mediated apoptosis.55

In EBV+ RA patients an increased frequency of CD25+ CD27+ memory cells are found. CD27 is shown to be critical for several steps of EBV infection, and CD27+ B cells are considered as a reservoir of EBV in the viral latency phases.56,57 CD27 expression has recently been identified as essential for combating EBV infection, because individuals with CD27 deficiency develop combined immunodeficiency, hypogammaglobulinaemia and persistent symptomatic EBV viraemia.58,59 Interestingly, it has been shown that B cells in the rheumatic synovia express latent membrane proteins 1 and 2A, the EBV-encoded proteins that provide additional survival and maturation signals to B cells.60 We show that patients with RA have an increase of CD25+ B cells in synovial fluid and in PB.

We have previously studied EBV-induced production of IL-6 by CD25+ B cells of healthy individuals and observed no differences compared with CD25– B cells.44 In the present study we investigated the direct effect of EBV on CD25+ cells in vitro and found that CD25+ B cells of patients with RA have increased immunoglobulin secretion following EBV stimulation. The EBV-induced immunoglobulin production pattern in patients with RA was different compared with the one observed in healthy controls. Patients with RA (n = 7) were good producers of IgG and IgM in CD19+ CD25+ cells. In contrast, negligible levels of IgG and IgM were measured in cultures of CD19+ CD25+ cells of healthy subjects (n = 2).

These findings emphasize that CD25+ B cells of patients with RA may quickly convert into antibody-secreting cells during EBV infection and may contribute to the exacerbation of inflammation in RA patients.

Conclusions

Infection with EBV affects the B-cell phenotype in patients with RA by increasing the CD25+ subset and by inducing their immunoglobulin production. These findings clearly link CD25+ B cells to the EBV-dependent sequence of reactions in the pathogenesis of RA.

Acknowledgments

Mikael B designed the study, performed laboratory work, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. MR performed laboratory work, analysed data and wrote the paper. Maria B designed the study, performed laboratory work, analysed data and wrote the manuscript.

Fundings

This work was supported by grants from the Commission of European Union (FP7 Health Programme, Gums & Joints no. 261460), the Swedish Medical Research Council (no. 521-2011-2417, no. 521-2008-2199),the Regional Agreement on Medical Training and Clinical Research between the Western Götaland County Council (LUA/ALF), the Ragnar och Torsten Söderberg Foundation, the Medical Society of Gothenburg, the Swedish Association Against Rheumatism, the Gothenburg Association Against Rheumatism, King Gustaf V's Foundation, the Nanna Swartz Foundation, the AME Wolff Foundation, Rune and Ulla Amlövs Trust, the Swedish Research Agency for Innovation Systems (VINNOVA/COMBINE), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Pharmacist Hedberg Foundation, the Magnus Bergwall Foundation, the Family Thölen and Kristlers Foundation, and the University of Gothenburg.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Takemura S, Klimiuk PA, Braun A, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. T cell activation in rheumatoid synovium is B cell dependent. J Immunol. 2001;167:4710–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wipke BT, Wang Z, Nagengast W, Reichert DE, Allen PM. Staging the initiation of autoantibody-induced arthritis: a critical role for immune complexes. J Immunol. 2004;172:7694–702. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossaers-Bakker KW, de Buck M, van Zeben D, Zwinderman AH, Breedveld FC, Hazes JM. Long-term course and outcome of functional capacity in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease activity and radiologic damage over time. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1854–60. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199909)42:9<1854::AID-ANR9>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tak PP, Bresnihan B. The pathogenesis and prevention of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis: advances from synovial biopsy and tissue analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2619–33. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2619::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, Stevens RM, Shaw T. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2572–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emery P, Deodhar A, Rigby WF, et al. Efficacy and safety of different doses and retreatment of rituximab: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial in patients who are biological naive with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate (Study Evaluating Rituximab's Efficacy in MTX iNadequate rEsponders (SERENE)) Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1629–35. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emery P, Fleischmann R, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, et al. The efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate treatment: results of a phase IIB randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1390–400. doi: 10.1002/art.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tak PP, Rigby WF, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Inhibition of joint damage and improved clinical outcomes with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: the IMAGE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:39–46. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.137703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tak PP, Rigby W, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Sustained inhibition of progressive joint damage with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year results from the randomised controlled trial IMAGE. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:351–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keystone EC, Cohen SB, Emery P, et al. Multiple courses of rituximab produce sustained clinical and radiographic efficacy and safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to 1 or more tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: 5-year data from the REFLEX study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:2238–46. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorner T, Lipsky PE. B-cell targeting: a novel approach to immune intervention today and tomorrow. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7:1287–99. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.9.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leandro MJ, Cambridge G, Ehrenstein MR, Edwards JC. Reconstitution of peripheral blood B cells after depletion with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:613–20. doi: 10.1002/art.21617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehnberg M, Amu S, Tarkowski A, Bokarewa MI, Brisslert M. Short- and long-term effects of anti-CD20 treatment on B cell ontogeny in bone marrow of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R123. doi: 10.1186/ar2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vos K, Thurlings RM, Wijbrandts CA, van Schaardenburg D, Gerlag DM, Tak PP. Early effects of rituximab on the synovial cell infiltrate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:772–8. doi: 10.1002/art.22400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cambridge G, Leandro MJ, Edwards JC, Ehrenstein MR, Salden M, Bodman-Smith M, Webster AD. Serologic changes following B lymphocyte depletion therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2146–54. doi: 10.1002/art.11181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De La Torre I, Leandro MJ, Valor L, Becerra E, Edwards JC, Cambridge G. Total serum immunoglobulin levels in patients with RA after multiple B-cell depletion cycles based on rituximab: relationship with B-cell kinetics. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2012;51:833–40. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottenberg JE, Ravaud P, Bardin T, et al. Risk factors for severe infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab in the autoimmunity and rituximab registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2625–32. doi: 10.1002/art.27555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatzidionysiou K, Lie E, Nasonov E, et al. Highest clinical effectiveness of rituximab in autoantibody-positive patients with rheumatoid arthritis and in those for whom no more than one previous TNF antagonist has failed: pooled data from 10 European registries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1575–80. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.148759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatzidionysiou K, Lie E, Nasonov E, et al. Effectiveness of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug co-therapy with methotrexate and leflunomide in rituximab-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients: results of a 1-year follow-up study from the CERERRA collaboration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:374–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quartuccio L, Fabris M, Salvin S, et al. Rheumatoid factor positivity rather than anti-CCP positivity, a lower disability and a lower number of anti-TNF agents failed are associated with response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2009;48:1557–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dass S, Rawstron AC, Vital EM, Henshaw K, McGonagle D, Emery P. Highly sensitive B cell analysis predicts response to rituximab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2993–9. doi: 10.1002/art.23902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fabris M, Quartuccio L, Lombardi S, et al. The CC homozygosis of the -174G>C IL-6 polymorphism predicts a lower efficacy of rituximab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:315–20. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sellam J, Hendel-Chavez H, Rouanet S, et al. B cell activation biomarkers as predictive factors for the response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis: a six-month, national, multicenter, open-label study. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:933–8. doi: 10.1002/art.30233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sellam J, Rouanet S, Hendel-Chavez H, et al. Blood memory B cells are disturbed and predict the response to rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3692–701. doi: 10.1002/art.30599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnusson M, Brisslert M, Zendjanchi K, Lindh M, Bokarewa MI. Epstein–Barr virus in bone marrow of rheumatoid arthritis patients predicts response to rituximab treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2010;49:1911–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raterman HG, Vosslamber S, de Ridder S, et al. The interferon type I signature towards prediction of non-response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R95. doi: 10.1186/ar3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thurlings RM, Boumans M, Tekstra J, et al. Relationship between the type I interferon signature and the response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3607–14. doi: 10.1002/art.27702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niller HH, Wolf H, Minarovits J. Regulation and dysregulation of Epstein–Barr virus latency: implications for the development of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity. 2008;41:298–328. doi: 10.1080/08916930802024772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holoshitz J. The rheumatoid arthritis HLA-DRB1 shared epitope. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:293–8. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328336ba63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saal JG, Krimmel M, Steidle M, et al. Synovial Epstein–Barr virus infection increases the risk of rheumatoid arthritis in individuals with the shared HLA-DR4 epitope. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1485–96. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1485::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stastny P. Association of the B-cell alloantigen DRw4 with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:869–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197804202981602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao QY, Rickinson AB, Gaston JS, Epstein MA. Disturbance of the Epstein–Barr virus–host balance in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a quantitative study. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;64:302–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alspaugh MA, Henle G, Lennette ET, Henle W. Elevated levels of antibodies to Epstein–Barr virus antigens in sera and synovial fluids of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:1134–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI110127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balandraud N, Meynard JB, Auger I, Sovran H, Mugnier B, Reviron D, Roudier J, Roudier C. Epstein–Barr virus load in the peripheral blood of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: accurate quantification using real-time polymerase chain reaction. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1223–8. doi: 10.1002/art.10933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tosato G, Steinberg AD, Yarchoan R, Heilman CA, Pike SE, De Seau V, Blaese RM. Abnormally elevated frequency of Epstein–Barr virus-infected B cells in the blood of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:1789–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI111388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babcock GJ, Decker LL, Freeman RB, Thorley-Lawson DA. Epstein–Barr virus-infected resting memory B cells, not proliferating lymphoblasts, accumulate in the peripheral blood of immunosuppressed patients. J Exp Med. 1999;190:567–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.4.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Depper JM, Zvaifler NJ. Epstein–Barr virus. Its relationship to the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:755–61. doi: 10.1002/art.1780240601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen A, Gergely P, Jondal M, Klein G, Britton S. Polyclonal Ig production after Epstein–Barr virus infection of human lymphocytes in vitro. Nature. 1977;267:52–4. doi: 10.1038/267052a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babcock GJ, Decker LL, Volk M, Thorley-Lawson DA. EBV persistence in memory B cells in vivo. Immunity. 1998;9:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joseph AM, Babcock GJ, Thorley-Lawson DA. Cells expressing the Epstein–Barr virus growth program are present in and restricted to the naive B-cell subset of healthy tonsils. J Virol. 2000;74:9964–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.9964-9971.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joseph AM, Babcock GJ, Thorley-Lawson DA. EBV persistence involves strict selection of latently infected B cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:2975–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amu S, Stromberg K, Bokarewa M, Tarkowski A, Brisslert M. CD25-expressing B-lymphocytes in rheumatic diseases. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65:182–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amu S, Tarkowski A, Dorner T, Bokarewa M, Brisslert M. The Human Immunomodulatory CD25+ B Cell Population belongs to the Memory B Cell Pool. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66:77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brisslert M, Bokarewa M, Larsson P, Wing K, Collins LV, Tarkowski A. Phenotypic and functional characterization of human CD25+ B cells. Immunology. 2006;117:548–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perfetto SP, Chattopadhyay PK, Roederer M. Seventeen-colour flow cytometry: unravelling the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:648–55. doi: 10.1038/nri1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roll P, Dorner T, Tony HP. Anti-CD20 therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: predictors of response and B cell subset regeneration after repeated treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1566–75. doi: 10.1002/art.23473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanz I, Wei C, Lee FE, Anolik J. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of human memory B cells. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amu S, Gjertsson I, Brisslert M. Functional characterization of murine CD25 expressing B cells. Scand J Immunol. 2010;71:275–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rehnberg M, Brisslert M, Amu S, Zendjanchi K, Hawi G, Bokarewa MI. Vaccination response to protein and carbohydrate antigens in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after rituximab treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R111. doi: 10.1186/ar3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kube D, Vockerodt M, Weber O, et al. Expression of Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 is associated with enhanced expression of CD25 in the Hodgkin cell line L428. J Virol. 1999;73:1630–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1630-1636.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahara M, Kis LL, Nagy N, Liu A, Harabuchi Y, Klein G, Klein E. Concomitant increase of LMP1 and CD25 (IL-2-receptor α) expression induced by IL-10 in the EBV-positive NK lines SNK6 and KAI3. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2775–83. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vockerodt M, Tesch H, Kube D. Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 activates CD25 expression in lymphoma cells involving the NFκB pathway. Genes Immun. 2001;2:433–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ibisch C, Saulquin X, Gallot G, Vivien R, Ferrand C, Tiberghien P, Houssaint E, Vie H. The T cell repertoire selected in vitro against EBV: diversity, specificity, and improved purification through early IL-2 receptor α-chain (CD25)-positive selection. J Immunol. 2000;164:4924–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pope RM. Apoptosis as a therapeutic tool in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:527–35. doi: 10.1038/nri846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al Tabaa Y, Tuaillon E, Bollore K, et al. Functional Epstein–Barr virus reservoir in plasma cells derived from infected peripheral blood memory B cells. Blood. 2009;113:604–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-136903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siemer D, Kurth J, Lang S, Lehnerdt G, Stanelle J, Kuppers R. EBV transformation overrides gene expression patterns of B cell differentiation stages. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:3133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salzer E, Daschkey S, Choo S, et al. Combined immunodeficiency with life-threatening EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorder in patients lacking functional CD27. Haematologica. 2012;98:473–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.068791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Montfrans JM, Hoepelman AI, Otto S, et al. CD27 deficiency is associated with combined immunodeficiency and persistent symptomatic EBV viremia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:787–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.013. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Croia C, Serafini B, Bombardieri M, et al. Epstein–Barr virus persistence and infection of autoreactive plasma cells in synovial lymphoid structures in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202352. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]