Abstract

Cyber victimization is an important research area; yet, little is known about aversive peer experiences on social networking sites (SNSs), which are used extensively by youth and host complex social exchanges. Across samples of adolescents (n=216) and young adults (n=214), we developed the Social Networking-Peer Experiences Questionnaire (SN-PEQ), and examined its psychometric properties, distinctiveness from traditional peer victimization, and associations with internalized distress. The SN-PEQ demonstrated strong factorial invariance and a single factor structure that was distinct from other forms of peer victimization. Negative SNS experiences were associated with youths’ symptoms of social anxiety and depression, even when controlling for traditional peer victimization. Findings highlight the importance of examining the effects of aversive peer experiences that occur via social media.

Keywords: cyber victimization, young adults, adolescents, depression, social anxiety, social networking

Substantial work has documented the pernicious effects of peer victimization on youth (Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001; Siegel, La Greca, & Harrison, 2009). Peer victimization refers to being the recipient of peer aggression (Hawker & Boulton, 2000), and most studies focus on overt (e.g., being hit, pushed, threatened) and relational (e.g., being socially excluded, manipulated by friends) forms of victimization (e.g., Prinstein et al., 2001). In particular, peer victimization contributes to youths’ symptoms of social anxiety and depression (La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Ranta, Kaltiala-Heino, Pelkonen, & Marttunen, 2009; Siegel et al., 2009), which in turn puts youth at risk for recurring peer victimization (La Greca & Lai, in press; Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010).

Cyber victimization, which occurs through electronic media (e.g., social networking, texting), is a growing and salient concern for youth (Kowalski & Limber, 2007; Williams & Guerra, 2007). Surveys reveal that 93–95% of US adolescents and young adults go online (Lenhart, Purcell, Smith, & Zickuhr, 2010). Moreover, about 80% of these online youth (defined as adolescents and young adults) use social networking sites (SNSs) – a dramatic increase in the past five years (Lenhart et al., 2011). Similarly, in the Netherlands, where 93% of the population aged 12 and older access the Internet, social media use has been on the rise (e.g., 76% increase in the Facebook use from 2010 to 2011), and 88% of those who actively use social media are under the age of 25 (European Travel Commission, 2012). Such findings underscore the need for empirical research on cyber forms of peer victimization, particularly as it occurs via social media.

One obstacle to such research is that few well-validated measures are available to examine peer victimization occurring through technology, and none specifically address victimization via SNSs. To address this limitation, we developed and evaluated the psychometric properties of a measure of aversive peer experiences that occur via SNSs, the Social Networking – Peer Experiences Questionnaire (SN-PEQ). A related study goal was to evaluate whether such aversive experiences are distinct from other forms of peer victimization that occur in person. Our final goal was to examine associations between aversive experiences on SNSs and youths’ symptoms of internalized distress.

Cyber Victimization Experiences in Social Networking

In developing the SN-PEQ, we focused on SNSs because their use has exploded in recent years, with close to one billion users worldwide for Facebook alone (Emerson, 2012). In the US, SNSs appear to be youths’ primary communication tool (Lenhart et al., 2011), and social media use among teens and young adults has expanded rapidly due to their accessibility via mobile devices (Lenhart et al., 2010).

Although most SNS experiences enhance adolescents’ friendships and social connections (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007; Valkenburg, Peter, & Schouten, 2006), negative experiences can occur. However, research on cyber victimization has not yet directly addressed aversive experiences occurring on SNSs, as it has focused mainly on experiences occurring via older communication tools (i.e., instant messaging, chat rooms) (Katzer, Fetchenhauer, & Belschak, 2009) that have declined in use (Lenhart et al., 2010), or has assessed cyber experiences very generally (Wang, Iannotti, Luk, & Nansel, 2010).

For example, a compendium of established victimization measures published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Hamburger, Basile, & Vivolo, 2011) identified only two measures of cyber victimization. One contained 9 items, predominately reflecting email and chat room experiences, with one item pertaining to social media (…has someone posted something on your MySpace page that made you upset or uncomfortable?) (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009). The other measure used an open-ended format wherein respondents provide an example of “harassment” using technology and then rate the event’s frequency and impact (Beran & Li, 2005). Similarly, other studies assessing youths’ cyber victimization experiences rely on one or two general questions (Li, 2006), or do not include items reflecting social networking (Tynes, Rose, & Williams, 2010).

Understanding youths’ aversive experiences on SNSs is important, given the prevalence, distinctiveness, and sophistication of this means of social interaction (Brown & Bobkowski, 2011). SNS users are often in “constant contact” with friends (Lenhart et al., 2011), and have access to large amounts of social information (friends’ location, activities, and feelings) that can be delivered to a wide audience (Brown & Bobkowski, 2011). Users also have access to pictures and weblinks posted by friends and may engage with others in cross-platform interactions (e.g., commenting to a friend on a SNS while participating in “real-world” events).

SNSs may also lend themselves to a variety of aggressive acts; in fact, 88% of teens using social media have observed others being mean or cruel on SNSs (Lenhart et al., 2011). Examples include ignoring or excluding others from activities, posting mean comments or embarrassing photos, or spreading rumors in a public manner. Through mobile devices, these aversive experiences are delivered in “real-time” to a wide audience (Brown & Bobkowski, 2011), which could enhance their impact. Older communication tools and in-person peer interactions do not offer this level of complexity, “constant contact,” or cross-platform interactions. Additionally, because definitions of cyber victimization vary (for review, see Tokunga, 2010), we currently have a limited understanding of how negative peer experiences on SNSs affect youth, and it is important to gather information from youths themselves.

Thus, in developing the SN-PEQ, we included multiple items to reflect the variety and complexity of interactions that occur via social media. Specifically, beginning with a sample of older adolescents or young adults (Study 1), who are the heaviest users of social media (Lenhart et al., 2010), we examined the factor structure of the SN-PEQ, and its reliability and concurrent validity (i.e., associations with other measures of peer victimization). Moreover, using an independent sample of adolescents (Study 2), we attempted to cross-validate the factor structure of the SN-PEQ and evaluate its measurement invariance over time. For both study samples, we expected that aversive peer experiences on SNSs could be represented by a single factor, given the unique features of SNSs (described above) and also because the other peer victimization types, overt and relational peer victimization, each have been represented by a single factor in previous research (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004).

Additionally, we examined gender differences in SN-PEQ scores in both study samples. Some investigators observed greater cyber victimization among girls than boys (e.g., Kowalski & Limber, 2007), but others found no gender differences (e.g., Katzer et al., 2009).

Related to the development of the SN-PEQ, an important aspect of this study was evaluating whether experiences captured by the SN-PEQ were empirically distinct from more “traditional” peer victimization (i.e., overt and relational victimization). Thus, we examined this issue in our primary sample of older adolescents or young adults (Study 1). Research has found overlap between cyber and traditional peer victimization, but has also highlighted some unique differences, including the constant accessibility of electronic media (Perren, Dooley, Shaw, & Cross, 2010). Thus, we expected that aversive experiences on SNSs would be distinct from overt and relational peer victimization, and we used statistical models to evaluate this issue empirically.

Finally, we note that our approach to examining aversive peer experiences on SNSs was a continuous and dimensional approach rather than a categorical one. Ample evidence suggests that continuous measures of peer victimization experiences are associated with youths’ adjustment problems (e.g., La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Prinstein et al., 2001; Storch, Masia-Warner, Crisp & Klein, 2005).

Victimization Experiences and Internalized Distress

Our remaining study goal was to examine associations between aversive experiences on SNSs and youths’ symptoms of internalized distress using our Study 1 sample. Emerging research suggests that cyber victimization, measured generally, is linked with youths’ symptoms of depression and social anxiety (Juvonen & Gross, 2008; Perren et al., 2010; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004), even after controlling for other forms of peer victimization (Dempsey, Sulkowski, Nichols, & Storch, 2009). However, research has not directly examined associations between aversive experiences that occur on social media and youths’ internalizing symptoms, despite the importance and high utilization of SNSs among adolescents and young adults (Brown & Bobkowski, 2011; Lenhart et al., 2010).

In developing the SN-PEQ, we expected that youths’ aversive peer experiences on social media would similarly be related to symptoms of social anxiety and depression. We examined this issue, while controlling for traditional forms of peer victimization and demographic characteristics. Moreover, given their high comorbidity (Starr, Davila, La Greca, & Landoll, 2011), symptoms of social anxiety and depression were jointly modeled and controlled in our analysis. This allowed us to examine the unique contributions of aversive SNS experiences to youths’ symptoms of social anxiety versus symptoms of depression.

Method

Participants

Study 1 participants were 216 ethnically-diverse older adolescents and young adults (63% females; Age: M =19.06 years, SD =1.28; 55% non-Hispanic White, 25% Hispanic, 8% Black, 12% Asian or Other). Most were college freshman or sophomores (83%) recruited from a private university in an urban area of the southeastern US. Students (n=108) were recruited from introductory psychology courses along with their best friend or romantic partner as part of a larger study on peer relationships. Most participants (69%) were in close-friend dyads and 30% were in romantic dyads; 1% did not indicate their type of affiliation. Each dyad member completed the study independently.

Study 2 participants were 214 ethnically-diverse adolescents (54% female, Age: M=15.72 years, SD =1.22; 75% Hispanic; 10% non-Hispanic White; 12% Black, 3% Asian or Other). Participants were recruited from two urban Southeastern US high schools with diverse socioeconomic status, as part of a study on peer relationships. A random subsample of this larger study was selected for the purpose of cross-validating the SN-PEQ; this subsample was comparable in size to the Study 1 sample.

Measures

Demographic Information and Internet Use

Participants completed questions that asked about their age, gender, and race or ethnicity. Participants also completed a question about the frequency of their Internet use (1 = Never, 5 = A Few Times a Week).

Social Networking - Peer Experiences Questionnaire (SN-PEQ)

The SN-PEQ was designed to assess aversive peer experiences via SNSs. An item pool was generated from two focus groups (three members each), conducted with adolescents and young adults (13–25 years) recruited from the university and community. Focus group members generated items after the prompt, “What are some things that you have done or have had done to you on social networking sites to make you upset or mad?” Four additional focus groups (two to six members each) were conducted to obtain feedback on whether participants had experienced similar events or had additional experiences to add. This process led to the development of 12 items, further refined based on input from peer relations experts. SN-PEQ items (Table 1) reflected a variety of aversive peer experiences. Participants rated occurrence of each item over the past two months on a 5-point scale (1 = Never, 5 = A Few Times a Week).

Table 1.

Distribution of SN-PEQ Items

|

CV-SNS Item A peer… |

Study 1 | Study 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Once or twice | A few times | Once/week | More often | Skewness (kurtosis) | Once or twice | A few times | Once/week | More often | Skewness (kurtosis) | |

| 1. …I wanted to be friends with on a social networking site (i.e., MySpace, Facebook) ignored my friend request. | 29% | 6% | 1% | 1% | 2.04 (5.37) | 23% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 1.41 (.97) |

| 2. …removed me from his/her list of friends on a social networking site. | 35% | 6% | 1% | 1% | 1.68 (4.30) | 36% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 0.88 (−0.20) |

| 3. …made me feel bad by not listing me in his/her “Top 8” or “Top Friends” list. | 19% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 2.68 (9.02) | 4% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 4.20 (18.15) |

| 4. …posted mean things about me on a public portion of a social networking site (SNS). | 14% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 2.89 (9.41) | 14% | 5% | 1% | 0% | 2.36 (4.60) |

| 5. …posted pictures of me on a SNS that made me look bad. | 27% | 7% | 1% | 0% | 1.47 (1.71) | 14% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 3.25 (12.35) |

| 6. …spread rumors about me or revealed secrets I had told them using public posts on a SNS. | 6% | 3% | 1% | 0% | 3.82 (15.30) | 12% | 6% | 2% | 1% | 2.78 (8.03) |

| 7. … sent me a mean message on a SNS. | 18% | 9% | 1% | 1% | 2.10 (4.56) | 25% | 9% | 1% | 1% | 1.79 (3.48) |

| 8. … pretended to be me on a SNS and did things to make me look bad/damage my friendships. | 14% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 3.23 (13.55) | 11% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 3.24 (12.32) |

| 9. …prevented me from joining a group on a SNS that I really wanted to be a part of | 3% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5.67 (30.45) | 5% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 4.04 (14.51) |

| 10. I found out that I was excluded from a party or social event over a SNS (i.e., MySpace, Facebook). | 24% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 2.18 (6.51) | 15% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 3.11 (11.72) |

| 11. … I was dating broke up with me using a SNS. | 6% | 1% | 0% | 1% | 6.32 (52.40) | 21% | 4% | 0% | 1% | 1.76 (2.12) |

| 12. … made me feel jealous by “messing” with my girlfriend/boyfriend on a SNS (i.e., posting pictures together, writing messages on a Facebook wall, ranking him/her in a “Top 8 or “Top Friends”). | 21% | 8% | 1% | 1% | 1.86 (3.46) | 23% | 9% | 2% | 1% | 1.79 (3.33) |

Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (R-PEQ; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004)

The R-PEQ assesses relational and overt peer victimization (3 items each). Participants rated occurrence of events in the past two months using a 5-point scale (1 = Never, 5 = A Few Times a Week). Subscale scores were calculated by averaging items. The R-PEQ has adequate reliability and convergent validity with other measures of peer victimization (La Greca & Harrison, 2005). R-PEQ reliability estimates over two months range between r = .43 – .52 for overt and relational victimization (Siegel et al., 2009). In Study 1, internal consistencies were α = .83 (relational) and α = .77 (overt). In Study 2, they were α = .81 (overt) and .72 (relational).

Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A; La Greca & Lopez, 1998)

The SAS-A is an 18-item measure assessing social anxiety (e.g., feeling shy around peers, avoiding peer interactions). Participants rated occurrence of events in the past two months on a 5-point scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = All the time). Total scores are calculated by summing all items. The SAS-A has been widely used with youth and demonstrates excellent reliability and validity (La Greca & Lopez, 1998). Internal consistency in Study 1 was α = .94.

Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977)

The CES-D is a 20-item measure assessing depressive symptoms. Participants rated how often they identified with each statement over the past two weeks. Items are scored 0 – 3 and totals are calculated by summing all items. The CES-D has been widely used with youth (Shean & Baldwin, 2008). Internal consistency in Study 1 was α = .87.

Analytic Approach

Preliminary analyses, internal consistency, and correlations were conducted in SPSS. Confirmatory factor analyses and structural model testing were conducted with Mplus.

In evaluating the SN-PEQ, items with skew ≥ 3 and kurtosis ≥ 10 were considered nonnormal (Kline, 2005) and log transformed. Skewed items with very low endorsement were removed from further consideration. Once the final item set was determined, a mean score for the SN-PEQ was calculated.

To account for data dependencies in Study 1 (i.e., the participants were recruited as dyads), all confirmatory factor analyses and structural equation models with Study 1 data were conducted with maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR), and alternative models were compared with the Sattora-Bentler Chi-Square Difference Test (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2007). Model fit was evaluated using cutoff criteria recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999: RMSEA ≤ .06, CFI ≥ .95, and SRMR ≤ .08), although these values are conservative (Little, Rehmtulla, Gibson, & Schoemann, in press); a CFI of .90 is often considered adequate fit (e.g., Carlo, Knight, McGinley, Zamboanga, & Jarvix, 2010).

Procedure

For both studies, approval was obtained from the university Institutional Review Board. For Study 1, participants provided written informed consent. Due to difficulties obtaining parental consent in a university setting, only individuals aged 18 years or older were eligible to participate. Participants completed measures in a research lab and received course credit for participation. All measures described above were completed in Study 1.

For Study 2, protocol approval additionally was obtained from the public schools. Teachers distributed letters and parental consent forms in English and Spanish to adolescents. Approximately 62% of students returned consent forms and 87% of those returning forms had permission to participate. Adolescents provided written assent prior to participation. Study 2 participants completed demographic information questions; they also completed the SN-PEQ and the Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire twice. We generated a random subsample of approximately 215 adolescents with complete data at two time points (6 weeks apart), selected from the larger sample (n=1162), using the SPSS “select cases” command. This created a subsample of adolescents (n=214), approximately equal in size to the Study 1 sample. Selected adolescents did not differ from unselected adolescents (n = 948) on any demographic or study variables, nor did they differ from those who had two waves of data available but were not randomly selected for inclusion (n= 716) (all ps > .05).

Results

Preliminary Descriptive Analyses

Based on the Study 1 sample, SN-PEQ items were analyzed for frequency and normality (see Table 1). Items 9 and 11 had very low endorsement and high skew; after consultation with experts in peer relationships, they were removed from analyses. Thus, 10 items were used to evaluate the SN-PEQ; mean scores were calculated by averaging these items.

Next, we examined the various types of peer victimization in the two study samples. Most youth reported at least some cyber victimization (82% Study 1; 78% Study 2) and relational peer victimization (83% Study 1; 69% Study 2). Fewer youth reported overt peer victimization (38% Study 1; 39% Study 2). In evaluating mean scores for the measures (see Table 2), across studies, relational peer victimization was higher than either cyber victimization (Study 1, t(207) = 11.44; Study 2, t(215) = 7.83, ps < .001) or overt peer victimization (Study 1, t(212) = 15.02; Study 2, t(215) = 6.64, ps < .001). Youth reported more cyber victimization than overt peer victimization in Study 1, t(206) = 6.59, but not in Study 2, t(215) = −0.25.

Table 2.

Means and Standardized Loadings for Confirmatory Factor Analyses of SN-PEQ

| A Peer… | Study 1

|

Study 2

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Means (SD) | Loadings | Means (SD) | Loadings | |

| SN-PEQ Items | ||||

| Ignored friend requests | 1.49 (.05) | .45 | 1.37 (.04) | .37 |

| Removed me from a “Friend List” | 1.53 (.05) | .59 | 1.47 (.04) | .46 |

| Did not list me in a “Friend List”b | 1.33 (.05) | .56 | 0.06 (.02) | .28 |

| Posted mean things on public site | 1.30 (.05) | .36 | 1.25 (.04) | .55 |

| Posted embarrassing picturesb | 1.46 (.05) | .40 | 0.15 (.02) | .48 |

| Spread rumors or revealed secretsa | 0.08 (.02) | .43 | 1.32 (.05) | .46 |

| Sent mean messages | 1.45 (.06) | .60 | 1.52 (.06) | .49 |

| Pretended to be mea, b | 0.14 (.02) | .52 | 0.13 (.02) | .29 |

| Excluded me from parties/social eventsb | 1.35 (.05) | .63 | 0.18 (.02) | .52 |

| Created jealousy with my romantic partner | 1.43 (.05) | .52 | 1.47 (.05) | .43 |

| SN-PEQ Total | 1.37 (.41) | 1.33 (.35) | ||

| PEQ -Relational | 1.91 (.72) | 1.65 (.70) | ||

| PEQ - Overt | 1.18 (.35) | 1.33 (.51) | ||

Item was log-transformed in Study 1.

Item was log-transformed in Study 2. All loadings were significant (p < .01).

SN-PEQ: Psychometric Properties

Using confirmatory factor analyses, we evaluated whether the SN-PEQ could be represented by a single latent factor (see Table 2). This single-factor model fit the data well for Study 1 (χ2(22) =23.87, p = .35; RMSEA = .02; CFI = .99; SRMR = .03). The single factor model also fit the data well for our Study 2 cross-validation sample (χ2(22) =27.78, p = .18; RMSEA = .03; CFI = .98; SRMR = .04). For both samples, all loadings were significant (p < .01) and acceptable (> .35 for Study 1, ≥ .28 for Study 2). Thus, all 10 items were retained.

Internal consistency of the SN-PEQ was acceptable in both samples of youth. In Study 1, α = .81; in Study 2, α = .74. These values are consistent with previous literature on traditional peer victimization, with internal consistencies ranging from .75–.84 for relational peer victimization and from .59 – .78 for overt victimization (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004; Siegel et al., 2009). In support of concurrent validity, mean SN-PEQ scores were moderately related to relational peer victimization (Study 1, r = .40; Study 2, r = .47, ps < .001) and to overt peer victimization (Study 1, r = .42; Study 2, r = .41, ps < .001).

In addition, using confirmatory factor analyses, we also examined latent gender differences in aversive social networking experiences in both samples of youth. Boys and girls did not differ on the SN-PEQ. For Study 1, the latent mean difference was −.03, p = .69; for Study 2, the latent mean difference was −.06, p = .14.

Finally, in Study 2 we examined the stability and measurement invariance of the SN-PEQ. The six-week retest stability was r = .50, p < .001. Next, we assessed measurement invariance of the SN-PEQ to determine if the measure functioned similarly across time. A measure with strong measurement invariance demonstrates similar factor loadings and item means over time. Thus, using analyses similar to Carlo et al. (2010), we tested a series of hierarchically nested factor structures. This series tested from the least restrictive model (all item loadings, means, and error variances can vary over time) to the most restrictive invariance models (all item factor loadings, means, and error variances are consistent over time); chi-square difference tests between the models determined which model should be retained. These analyses revealed that the SN-PEQ demonstrated strong factorial invariance, indicating that both the item factor loadings and means were similar across time. Specifically, the fit indices for this model were: χ2(144) = 210.64, p < .01, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .94, SRMR = .06.

Distinction Between Cyber and Peer Victimization

To evaluate whether SN-PEQ measured negative experiences that were distinct from other forms of peer victimization, we used confirmatory factor analyses to compare a three-factor model of peer victimization (i.e., overt, relational, and cyber experiences) with a two-factor model (i.e., overt versus relational and cyber experiences as one factor), and a one-factor model (i.e., all three peer victimization types combined). Error terms were allowed to correlate within latent constructs. Using the Study 1 sample, only the three-factor model fit the data well, χ2(85) =104.70, p = .07, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .97, and SRMR = .05 (see Table 3). The two-factor fit indices were: χ2(87) =174.70, p < .001, RMSEA = .07, CFI = .88, SRMR = .07; the one-factor fit indices were: χ2(88) =197.25, p < .001, RMSEA = .08, CFI = .84, SRMR = .07. Further, the three-factor model exhibited significantly better fit than the two-factor, TRd (2)=20.88, p = < .001, and one-factor model, TRd (3)=36.86, p = < .001.

Table 3.

Standardized Loadings for the Three-Factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Variables | A peer… | Study 1 | Study 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SN-PEQ | Ignored friend requests | .50 | .37 |

| Removed me from a “Friend List” | .63 | .46 | |

| Did not list me in a “Friend List”b | .64 | .28 | |

| Posted mean things on public site | .35 | .55 | |

| Posted embarrassing picturesb | .32 | .48 | |

| Spread rumors or revealed secretsa | .40 | .46 | |

| Sent mean messages | .54 | .49 | |

| Pretended to be mea,b | .54 | .29 | |

| Excluded me from parties/social eventsb | .61 | .52 | |

| Created jealousy with my romantic partner | .48 | .43 | |

|

| |||

| PEQ: Relational | Excluded me from an activity or conversation | .56 | .19 |

| Did not invite me to a party/social event | .96 | .31 | |

| Left me out of what they were doing | .69 | .68 | |

|

| |||

| PEQ: Overt | Threatened to hurt or beat me | .70 | .55 |

| Hit, kicked, or pushed me | .49 | .79 | |

| Chased me | .93 | .66 | |

Note.

Item was log-transformed in Study 1.

Item was log-transformed in Study 2. All loadings were significant (p < .01).

Finally, the three-factor solution (with correlated within-factor error terms) was cross-validated with the Study 2 sample (Table 3). Additional error terms for the SN-PEQ indicators were allowed to correlate, given that this was a different, younger sample. The three-factor solution showed acceptable fit, χ2(78) =116.91, p < .01, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .95, SRMR = .05.

Cyber Experiences and Internalized Distress

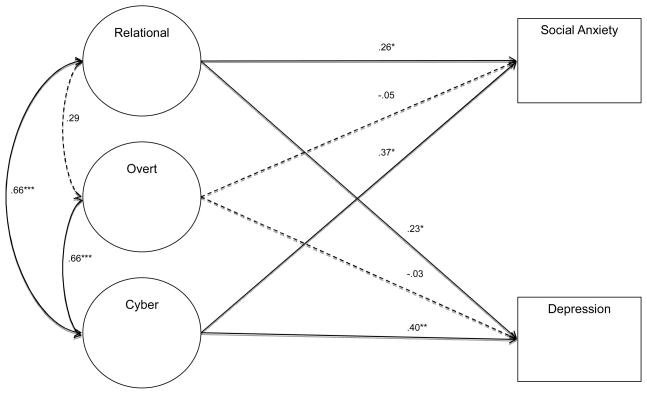

Our final aim was to examine associations between youths’ negative peer experiences on SNSs and symptoms of social anxiety and depression in our Study 1 sample (see Figure 1). Frequency of SNS use was evaluated and discarded as a potential control variable; it was not correlated with individual SN-PEQ items (rs = .02 to .10, ps > .05) or with mean SN-PEQ scores (r = −.04, p > .05).

Figure 1.

Study 1: Associations between peer victimization types and internalizing symptoms. For figure clarity, indicators, residual covariances, and control variables were omitted. Parameter estimates are standardized values. Solid lines indicate significant paths.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

This model demonstrated acceptable fit, χ2(176) = 255.78, p < .001, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .06. Demographic variables, including race or ethnicity (dummy coded with Black, Hispanic, and Others as the identified group versus White as the reference group) and gender (dummy coded with male as the identified group, female as the reference group) were included in the model. However, these demographic variables were not significantly associated with either social anxiety or depressive symptoms. With all variables controlled, the significant structural paths revealed that youths’ cyber experiences on the SN-PEQ were associated with greater symptoms of social anxiety, β = .37, p < .05, and depression, β = .40, p < .01. In addition, youths’ reports of relational peer victimization were also significantly associated with social anxiety (β = .26, p = .04) and depressive symptoms (β = .23, p = .04).

Discussion

We developed and evaluated a measure of aversive peer experiences via SNSs, the Social Networking – Peer Experiences Questionnaire, which appears appropriate for use with adolescents and young adults. Initial psychometric data were promising, and the aversive experiences assessed by the SN-PEQ appeared related to, but distinct from, other forms of peer victimization. Finally, older adolescents and young adults’ aversive experiences on SNSs were associated with symptoms of both social anxiety and depression.

Aversive Peer Experiences on Social Media

Cyber victimization is a growing concern for youth (Kowalski & Limber, 2007); yet, little research has focused on peer victimization that occurs via social media, despite its widespread use (Lenhart et al., 2011). Thus, the availability of the SN-PEQ may help to advance our understanding of the impact of youths’ social communication experiences on their social and emotional development. Our use of a “dimensional” approach to assessing aversive peer experiences occurring on social media allows for the study of the incremental contributions of such aversive experiences to youths’ overall well-being.

Studies 1 and 2 provided support for the psychometric properties of the SN-PEQ with adolescents and young adults. The SN-PEQ demonstrated a single factor structure and good internal consistency across both study samples. It also demonstrated strong measurement invariance over six weeks among adolescents.

Importantly, across both samples, we obtained support for the concurrent validity of the SN-PEQ and for the distinctiveness of this potential form of peer victimization. In both samples, aversive experiences on SNSs were moderately and significantly related to overt and relational peer victimization. Analyses also revealed a better model fit when aversive SNS experiences were treated as distinct from overt and relational peer victimization. Minor variations across the samples may reflect developmental differences in the way aversive experiences occur for high school aged adolescents versus older adolescents or young adults and warrant further study. For example, among younger adolescents, certain behaviors may be more or less socially acceptable, or may elicit different reactions from peers when the behaviors occur.

Overall, findings support the construct validity of the SN-PEQ with adolescents and young adults, who are key users of social media. Although most youth (69–83%) report that peers are kind to one another on social media (Lenhart et al., 2011), our findings also indicate that it is common for youth to report at least some aversive experiences on SNSs.

Despite our promising findings, several issues will be important in the future. Specifically, we did not compare the SN-PEQ with other measures of cyber victimization measures. Previously used measures have been very general (Wang et al., 2010), or were not specific to experiences that occur on social media; as such, we feel that the SN-PEQ likely captures the unique and nuanced aspects of youth’s behavior on social networking sites to a better extent than the more general items or measures that have been used. However, in the future, it would be valuable to understand how the aversive experiences assessed by the SN-PEQ relate to other online victimization experiences, especially ones perpetrated by peers. Comparing the SN-PEQ with other cyber measures might also enhance support for the convergent validity of the scale. Such data would add to our findings of strong associations between the SN-PEQ and measures of face-to-face peer victimization, consistent with previous literature (Perren et al., 2010). Additionally, it will be of interest to examine how the SN-PEQ could be used in a categorical manner to identify highly cyber victimized youth.

Aversive Experiences and Internalized Distress

We examined potential psychological implications of youths’ aversive peer experiences via SNSs. As expected, such experiences were significantly and positively associated with youths’ symptoms of depression and social anxiety. Notably, this was the case even when controlling for other forms of peer victimization and also controlling for comorbid symptomatology, which is rarely done (Starr et al., 2011). Moreover, relational peer victimization also contributed to youths’ symptoms of social anxiety and depression. These findings add to the growing literature on the role of peer and cyber victimization on the mental health of adolescents and young adults (Gros, Gros, & Simms, 2010), and highlight a potential peer risk factor for the development or maintenance of internalizing problems (La Greca & Lai, in press).

Our findings highlight aversive peer experiences on SNSs and also relational peer victimization as important interpersonal stressors. Conceptually and empirically, interpersonal stressors represent a shared pathway in the development of social anxiety and depression (La Greca & Lai, in press). Problems in interpersonal functioning have been featured in interpersonal theories of depression (Coyne, 1976), and in the development of social anxiety (La Greca & Lai, in press; Starr et al., 2011). Interestingly, overt peer victimization was not associated with social anxiety or depressive symptoms when controlling for relational and cyber experiences. This non-significant finding may be due to the shared variance between overt and other peer victimization types. Also, among older adolescents and young adults, overt peer victimization experiences may be relatively uncommon. The non-significant findings with overt peer victimization and significant findings with relational peer victimization mirror those of previous research that controlled for multiple types of peer victimization (La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Storch et al., 2005).

As an important next step, prospective studies are needed to enhance our understanding of potential bi-directional influences between aversive peer experiences that occur on social media and youths’ feelings of social anxiety and depression. Recent studies demonstrate bidirectional linkages between relational victimization and youths’ social anxiety (Siegel et al., 2009) and depressive symptoms (McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Hilt, 2009). A similar approach with aversive peer experiences on social media has the potential to add to our understanding of shared and unique risk factors involved in youths’ psychological adjustment.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the important contributions of this study, several limitations should be considered. First, the SN-PEQ focuses on a specific aspect of youths’ online experiences: those occurring via SNSs. We choose this focus due to the sharp increase and large percentage of youths using social networking (e.g., Lenhart et al., 2011; European Travel Commission, 2012), the exposure of youth to aggressive acts via social networking sites (88% of teen users; Lenhart et al., 2011), as well as the features of social networking sites which are unique from other forms of media: their complexity, the “constant contact” nature of interactions on these sites and the opportunity to engage in cross-platform interactions (i.e., interacting on a social networking site while engaging in another media or face-to-face interaction). However, it is important to note that research incorporating other measures of Internet-based peer victimization (e.g., email or texting), would enhance our understanding of cyber victimization and its impact.

Second, our samples focused on youth in academic or school settings. In particular, the convenience sample of psychology undergraduates may limit generalizability. However, use of the second sample, which captures a diverse population of adolescent youth in the United States during a period of compulsory education, enhances the generalizability of this study. We note that other available measures of peer victimization for adolescents (e.g., Peer Experiences Questionnaire; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004) also have been developed with school-based populations of adolescents. Moreover, none of the SN-PEQ items rely on events that would only affect youth in academic or school settings; in fact, social networking use is widespread among adolescents and young adults from diverse backgrounds (Lenhart et al., 2011). Thus, it is likely that the SN-PEQ functions well for youth across diverse settings, although this could be explored further in future research.

Third, although our two study samples were ethnically diverse, they differed considerably in their ethnic composition. However, ethnicity was not related to social anxiety or depressive symptoms in Study 1, nor was it related to SN-PEQ scores in either of our samples. Nevertheless, it could be useful for future research to explore whether ethnicity plays a role in youths’ experience of cyber victimization. Also of interest, may be cross-cultural differences in youths’ cyber victimization experiences. At the present time, use of social media in the US is extremely high among youth (e.g., Lenhart et al, 2011), and is becoming more common in other countries. For example, among 16 – 24 year olds in Finland, 73% use the Internet several times a day and 86% followed a social network service in the past 3 months (Official Statistics of Finland, 2011). Thus, given our similar findings for the SN-PEQ across the two samples, as well as research outside academic settings on adolescent media use (Lenhart et al. 2011), it is likely that the SN-PEQ functions well for youth across a variety demographic considerations.

In closing, this study advances our understanding of peer victimization experiences. It provides a useful tool for examining aversive cyber experiences and their associations with youths’ psychological functioning and other aspects of development. Although most peer experiences on SNSs are positive, findings suggest the importance of developing preventive interventions to reduce the likelihood of youth experiencing cyber victimization via SNSs. Strategies for improving youths’ handling of peer victimization experiences in general may help to reduce aversive cyber experiences. Also, Dooley and colleagues (2012) found that adolescents who respond to cyber victimization assertively (as opposed to aggressively) experience less adjustment difficulties. Thus, it may be useful to encourage youth to engage positively with SNSs and handle any negative experiences with thoughtful, non-aggressive, but assertive responses.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by research funds from a Cooper Fellow Award and UM Flipse Award presented to the 2nd author. Research time for the preparation of this manuscript was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; T32HD07510) awarded to the 3rd author.

Contributor Information

Ryan R. Landoll, Email: r.landoll@umiami.edu, Department of Psychology, University of Miami, 5665 Ponce de Leon Blvd., Coral Gables, FL 33124

Annette M. La Greca, Email: alagreca@miami.edu, Cooper Fellow, Professor of Psychology and Pediatrics, Director of Clinical Training, University of Miami, (305) 284-5222, ext. 1.

Betty S. Lai, Email: blai@med.miami.edu, Departments of Pediatrics and Psychology, University of Miami, 5665 Ponce de Leon Blvd., Coral Gables, FL 33124

References

- Beran T, Li Q. Cyber-harrassment: A study of a new method for an old behavior. Journal of Educational Computing Research. 2005;32:265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Bobkowski P. Older and newer media: Patterns of use and effects on adolescents’ health and well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Knight G, McGinley M, Zamboanga B, Jarvis L. The multidimensionality of prosocial behaviors and evidence of measurement equivalence in Mexican American and European American early adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(2):334– 358. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Prinstein M. Applying depression-distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:325–335. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey A, Sulkowski M, Nichols R, Storch E. Differences between peer victimization in cyber and physical settings and associated psychosocial adjustment in early adolescence. Psychology in the Schools. 2009;46:962–972. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley J, Shaw T, Cross D. The association between the mental health and behavioural problems of students and their reactions to cyber-victimization. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2012;9:275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12(4):Article 1. Retrieved from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol12/issue4/ellison.html. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R. Facebook users expected to pass 1 billion in august: icrossing. Huffington Post. 2012 Jan; Retrieved from: Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/01.

- European Travel Commission. Netherlands: Usage patterns. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.newmediatrendwatch.com/markets-by-country/10-europe/76-netherlands.

- Gros D, Gros K, Simms L. Relations between anxiety symptoms and relational aggression and victimization in emerging adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34:134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger M, Basile K, Vivolo A. Measuring bullying victimization, perpetration and bystander experiences: A compendium of assessment tools. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hawker D, Boulton M. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja S, Patchin J. Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler P. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Gross E. Extending the school grounds? Bullying experiences in cyberspace. Journal of School Health. 2008;78:496–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzer C, Fetchenhauer D, Belschak F. Cyberbullying: Who are the victims? A comparison of victimization in internet chatrooms and victimization in school. Journal of Media Psychology. 2009;21:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski R, Limber S. Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:S22–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison H. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Lai B. The role of peer relationships in youth psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach. In: Chu B, Ehrenreich-May J, editors. Transdiagnostic mechanisms and treatment of youth psychopathology. New York: Guilford; in press. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Lopez N. Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1022684520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Madden M, Smith A, Purcell K, Zickuhr K, Rainie L. Teens, kindness and cruelty on social networking sites. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K. Social media and young adults: Social media and mobile internet use among teens and young adults. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. Cyberbullying in schools: A research of gender differences. School Psychology International. 2006;27:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Little T, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, Schoemann A. Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods. doi: 10.1037/a0033266. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K, Hatzenbuehler M, Hilt L. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(5):894– 904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Official Statistics of Finland. Use of information and communications technology [e-publication] 2011 Retrieved from http://www.tilastokeskus.fi/til/sutivi/2011/sutivi_2011_2011-11-02_tie_001_en.html.

- Perren S, Dooley J, Shaw T, Cross D. Bullying in school and cyberspace: Associations with depressive symptoms in Swiss and Australian adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2010;4:28. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein M, Boergers J, Vernberg E. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Pelkonen M, Marttunen M. Associations between peer victimization, self-reported depression and social phobia among adolescents: The role of comorbidity. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:77–93. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis J, Prinzie P, Telch M. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shean G, Baldwin G. Sensitivity and specificity of depression questionnaires in a college-age sample. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2008;169:281–288. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.169.3.281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, La Greca AM, Harrison H. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescents: Prospective and reciprocal relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1096–1109. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr L, Davila J, La Greca AM, Landoll R. Social anxiety and depression: The teenage and early adult years. In: Alfano C, Biedel D, editors. Social anxiety disorder in adolescents and young adults: Translating developmental research into practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Storch E, Masia-Warner C, Crisp H, Klein R. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescence: A prospective study. Aggressive Behavior. 2005;31:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Tokunga R. Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010;26:277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Tynes B, Rose C, Williams D. The development and validation of the online victimization scale for adolescents. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 2010;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P, Peter J, Schouten A. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyber Psychology and Behavior. 2006;9:584–590. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Iannotti R, Luk J, Nansel T. Co-occurrence of victimization from five subtypes of bullying: Physical, verbal, social exclusion, spreading rumors, and cyber. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:1103–1112. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Guerra N. Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:S14–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra M, Mitchell K. Online aggressor/targets, aggressors, and targets: A comparison of associated youth characteristics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1308–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]