Significance

Brain development is characterized by critical periods (CPs) during which neural circuitry is especially sensitive to experience. The changes in cellular plasticity mechanisms that distinguish these CPs from other developmental windows and how these windows open and close remain poorly understood. Here we show that the opening of the classical visual system CP is characterized by a switch in sign of synaptic plasticity at a class of GABAergic synapse known to be important for CP timing.

Keywords: LTP, LTD, FS cell

Abstract

Sensory microcircuits are refined by experience during windows of heightened plasticity termed “critical periods” (CPs). In visual cortex the effects of visual deprivation change dramatically at the transition from the pre-CP to the CP, but the cellular plasticity mechanisms that underlie this change are poorly understood. Here we show that plasticity at unitary connections between GABAergic Fast Spiking (FS) cells and Star Pyramidal (SP) neurons within layer 4 flips sign at the transition between the pre-CP and the CP. During the pre-CP, coupling FS firing with SP depolarization induces long-term depression of inhibition at this synapse, whereas the same protocol induces long-term potentiation of inhibition at the opening of the CP. Despite being of opposite sign, both forms of plasticity share expression characteristics—a change in coefficient of variation with no change in paired-pulse ratio—and depend on GABAB receptor signaling. Finally, we show that the reciprocal SP→FS synapse also acquires the ability to undergo long-term potentiation at the pre-CP to CP transition. Thus, at the opening of the CP, there are coordinated changes in plasticity that allow specific patterns of activity within layer 4 to potentiate feedback inhibition by boosting the strength of FS↔SP connections.

Sensory microcircuits are refined by experience during windows of heightened plasticity termed “critical periods” (CPs). In visual cortex the classical CP was defined based on when visual deprivation (VD) induces ocular dominance (OD) shifts, between approximately postnatal days (P) 20–33 (1–3). However, visual cortex is also plastic during a pre-CP between eye opening (∼P14) and the onset of the classical CP (4–6). Although both developmental windows are characterized by sensitivity to visual experience, the effects of VD change dramatically at the transition between these two developmental stages (7–10).

The cellular changes that underlie the transition from pre-CP to CP plasticity remain incompletely understood, but recent work has implicated a specific inhibitory network involving parvalbumin-positive fast-spiking (FS) basket cells in this process (8, 11, 12). FS cells provide strong somatic inhibition onto cortical pyramidal neurons, and this inhibition matures significantly between eye opening and the opening of the classical CP (13–15). Further, reducing or enhancing this inhibition can prevent or prematurely trigger the transition from pre-CP to CP plasticity (11, 16–18). Thus, maturation of FS inhibition is thought to be causally involved in triggering CP plasticity, but exactly what aspect of this maturation drives these changes is unknown. One characteristic of this maturation is a change in the response of FS synapses to VD. Brief monocular VD during the pre-CP decreases inhibitory synaptic strength from FS to star pyramidal (SP) neurons in layer 4 (L4) of the monocular primary visual cortex [V1m (19)] but increases inhibition at the same synapse when performed during the CP (20). There is evidence that long-term potentiation of inhibition (LTPi) is the cellular mechanism behind the VD-driven inhibitory potentiation during the CP (20), but why VD weakens this synapse during the pre-CP has not been determined.

To ask whether a change in the cellular plasticity mechanisms present at FS→SP synapses might underlie this developmental shift in the effects of VD, we used paired recordings to analyze transmission and plasticity at unitary connections between FS cells and SP neurons within V1m. We found only subtle changes in the basal properties of this connection between P15–P17 (the pre-CP) and P21–P23 (the opening of the CP). In contrast, plasticity at this synapse changed dramatically. Coupling presynaptic FS firing with postsynaptic SP depolarization induced long-term depression of inhibition (LTDi) during the pre-CP, whereas the same protocol induced LTPi during the CP. Both forms of plasticity were accompanied by changes in the coefficient of variation (CV) of unitary inhibitory postsynaptic current (uIPSC) amplitude without significant changes in paired-pulse ratio (PPR) and were blocked by GABAB receptor (GABABR) antagonists. Finally, we found that during the CP (but not the pre-CP) the same induction protocol at reciprocally connected FS↔SP pairs induced LTP of both connections, suggesting that during the CP both components of this feedback inhibitory loop within L4 can be potentiated as a unit.

Results

To probe for developmental changes in the synaptic properties of FS→SP synapses, we performed multiple whole-cell recordings between P15 and P23 in L4 of the monocular portion of rat primary visual cortex (V1m). Excitatory SP and FS GABAergic inhibitory neurons were targeted and identified as described (19, 20). To probe unitary synaptic strength we elicited action potentials (APs) in the presynaptic FS cell and recorded the uIPSCs in SP neurons at three developmental stages: the pre-CP (P15–P17), a transition period (P18–P20), and the onset of the CP (P21–P23) (Fig. 1).

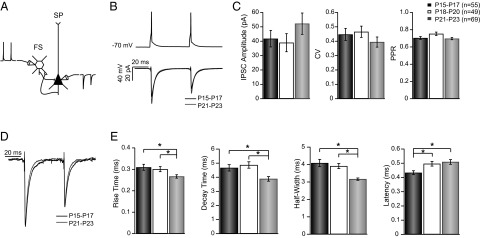

Fig. 1.

Development of unitary FS→SP connection properties. (A) Diagram of the experimental scheme. (B) Average uIPSC at P15–P17 (black) and P21–P23 (gray). (C) Plots summarizing the baseline amplitude, CV, and PPR for connections recorded at P15–P17 (black), P18–P20 (white), and P21–P23 (gray). (D) Peak-scaled average uIPSCs at P15–P17 (black) and P21–P23 (gray) to illustrate change in kinetics. (E) Plots of kinetic parameters for the three groups [P15–P17 (black), P18–P20 (white), and P21–P23 (gray)]. *P < 0.01.

Maturation of Unitary FS→SP Connections.

The strength of L4 GABAergic inhibition increases between eye opening and P30 (21). To assess the development of unitary FS→SP connections we compared the amplitude, CV, PPR, and kinetics of these connections for the three different age groups. This revealed no significant difference in the average uIPSC amplitude between groups (Fig. 1C, Left; P15–P17, n = 55; P18–P20, n = 49; P21–P23, n = 69; Kruskall–Wallis, P = 0.24), although there was a trend toward increased strength at the oldest age. Other synaptic parameters such as CV (Fig. 1C, Center) and PPR (Fig. 1C, Right) also were not significantly different across this developmental period (Kruskall–Wallis, P = 0.13 and P = 0.06, respectively).

GABAARs at many synapses undergo a developmental change in subunit composition that confers an age-dependent change in IPSC kinetics (21–23). In keeping with this, uIPSCs recorded at the onset of the CP were significantly faster than at earlier ages (Fig. 1D), with shorter rise and decay times (Fig. 1E; P < 0.001 for both rise time and decay time). In addition, there were changes in passive properties of SP neurons (RinP15–P17: 507.71 ± 19.98 MΩ; RinP18–P20: 317.18 ± 16.75 MΩ; RinP21–P23: 317.7 ± 11.58 MΩ; P < 0.001, Dunn–Holland–Wolfe test; CmP15–P17: 156.84 ± 4.34 pF; CmP18–P20: 191.23 ± 6.61 pF; CmP21–P23: 181.525 ± 5.12 pF; P < 0.001, Dunn–Holland–Wolfe test), but because these changes preceded the acceleration in uIPSC kinetics, they are unlikely to account for them.

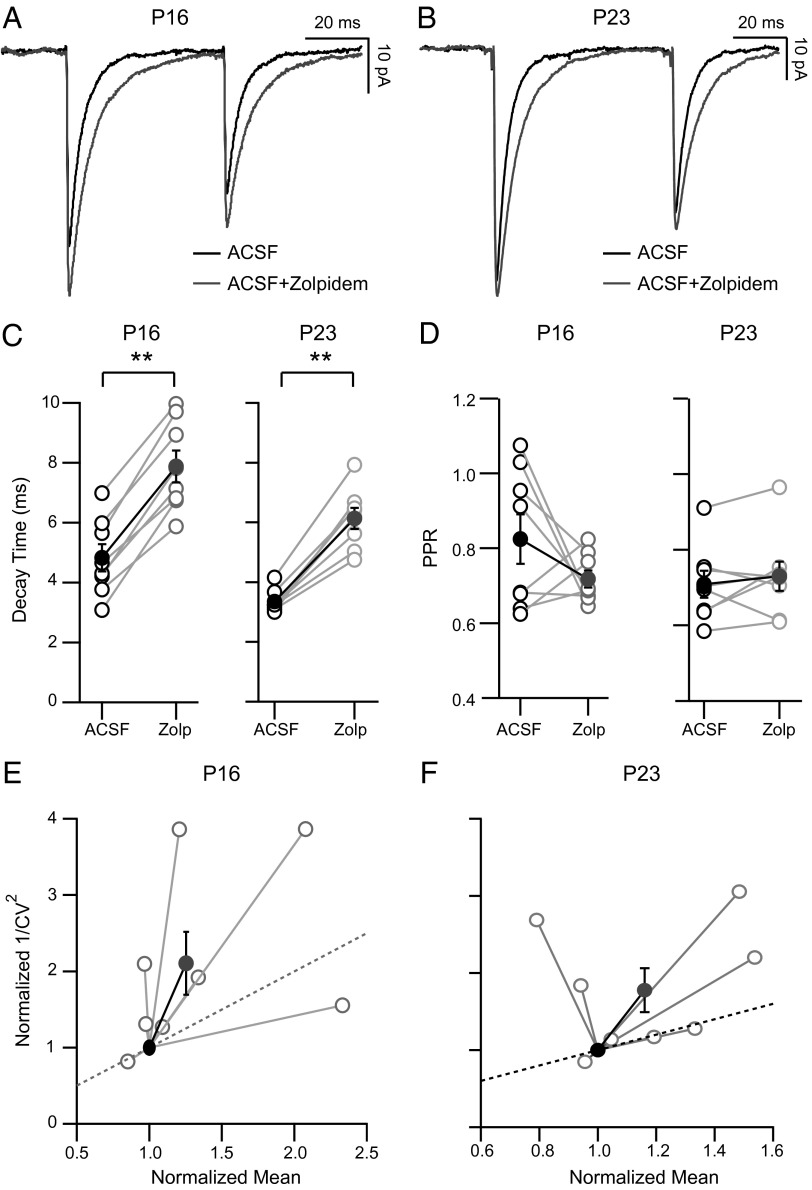

At some synapses, zolpidem-sensitive GABAARs are present at both presynaptic and postsynaptic sites, and modulation of these receptors can influence both presynaptic and postsynaptic aspects of neurotransmission (24). To test whether FS→SP synaptic connections are affected by zolpidem similarly during the pre-CP and CP, we washed in zolpidem during paired recordings (Fig. 2; n = 8 at both ages). We found a nearly identical response to zolpidem at both ages: mean uIPSC decay times were prolonged (Fig. 2 A–C; P < 0.01), and CV was decreased (P = 0.023) with no substantial effect on PPR (Fig. 2D; PPre-CP = 0.25; PCP = 0.38). A plot of 1/CV2 vs. the normalized mean amplitude revealed that at both ages, most points were above the unity line, suggestive of a presynaptic effect (Fig. 2 E and F) (25). These data suggest that zolpidem has a complex mixture of presynaptic and postsynaptic effects at FS→SP synapses that are expressed at both ages. Taken together, these data demonstrate relatively subtle changes in the basal properties of unitary FS→SP synapses between the pre-CP and CP. This suggests that changes in basal transmission are unlikely to account for the opposite effects of VD on synaptic strength at this synapse during the pre-CP and the CP.

Fig. 2.

The GABAAR modulator zolpidem has both presynaptic and postsynaptic effects on unitary FS→SP synapses. (A and B) Average uIPSCs recorded in ACSF and ACSF + zolpidem at P15–P16 (A) and P21–23 (B). (C) Effects of zolpidem wash-in on uIPSC decay and (D) PPR, at the two ages [ACSF (black) and ACSF + zolpidem (white); closed circles are means]. (E and F) Plots of the normalized 1/CV2 versus normalized mean IPSC amplitude for the two ages. Lines to open circles represent change for individual pairs after zolpidem wash-in, and filled circles represent the averages for each age. **P < 0.01.

Developmental Profile of Long-Term Plasticity at FS→SP Synapses.

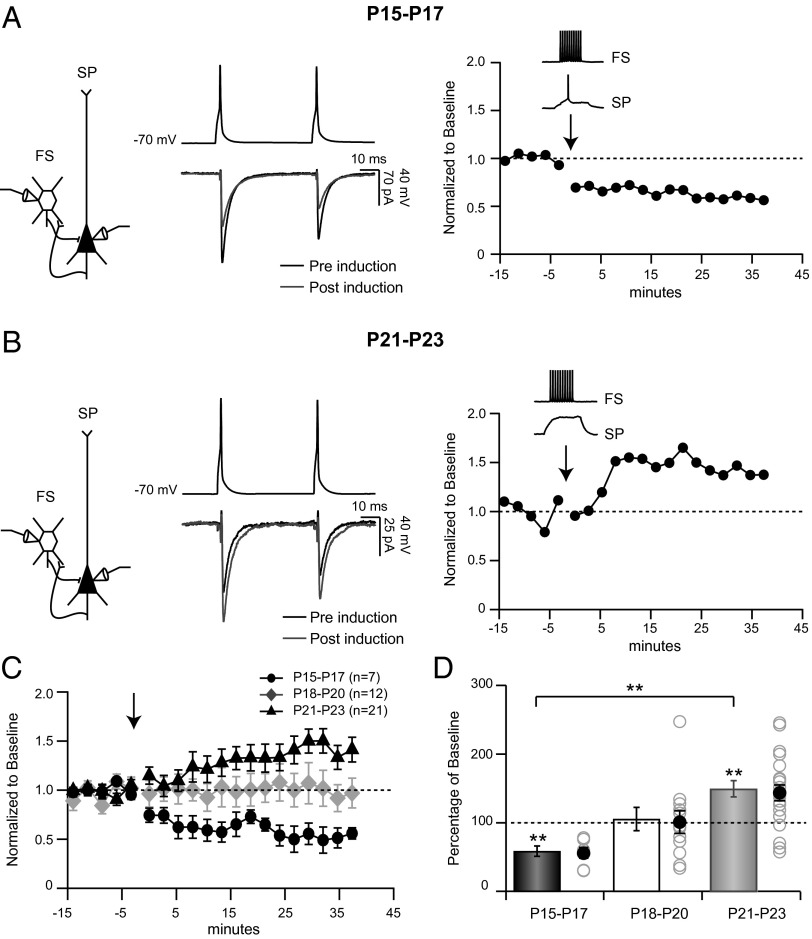

We next asked whether the expression of synaptic plasticity at unitary FS→SP connections changes during development (Fig. 3). At the opening of the CP this synapse expresses LTPi that can be reliably induced by coupling presynaptic firing with mild postsynaptic depolarization (to elicit no or only a few postsynaptic spikes) (20). Here we used this same induction paradigm to compare plasticity at this synapse during the pre-CP and the CP. Strikingly, during the pre-CP (P15–P17) this protocol did not induce LTPi but instead induced LTDi (Fig. 3A). In contrast, when the same induction protocol was applied to inhibitory connections after the onset of the CP (P23; Fig. 3B), FS→SP synaptic strength was strongly potentiated, as previously described (20). Overall, FS→SP synaptic connections underwent LTDi during the pre-CP (Fig. 3 C and D; n = 7; P = 0.015), no net change at the cusp of the CP (n = 12; Plower tail = Pupper tail = 0.51), and a reliable LTPi at the onset of the CP (n = 21; P < 0.01). Presynaptic firing without postsynaptic depolarization had no effect on uIPSC amplitude (103.14 ± 7.2% of baseline; n = 9; P = 0.3), as described previously (20).

Fig. 3.

The sign of plasticity induced by pairing FS and SP activity is developmentally regulated. (A) Example showing effects of pairing FS firing with SP depolarization at P16 on uIPSCs (black, preinduction; gray, postinduction) and the timeline of the change in uIPSC amplitude (Right); here and in subsequent figures, arrow marks time of pairing. (B) Example showing effects of pairing FS firing with SP depolarization at P23 on uIPSCs (black, preinduction; gray, postinduction) and the timeline of the change in IPSC amplitude (Right). (C) Average time course of change in uIPSC amplitude after induction for P15–P17 (black circles), P18–P20 (gray diamonds), and P21–P23 (black triangles). (D) Degree of plasticity at P15–P17 (black), P18–P20 (white), and P21–P23 (gray). Bars and filled circles are average, and open circles are individual pairs. **P < 0.01.

LTDi and LTPi were characterized by an increase or decrease (respectively) in CV of the first IPSC in the train (LTDi: 135.02 ± 8.78% of baseline, P < 0.02; LTPi: 90.82 ± 5.52% of baseline, P < 0.05) with no difference in PPR for either direction of plasticity (LTDi: 107.05 ± 8.72% of baseline, P = 0.94; LTPi: 97.37 ± 3.51% of baseline, P = 0.49). This matches well the profile of plasticity at this synapse during VD: reduced amplitude, increased CV, and little or no change in PPR during the pre-CP (19) and increased amplitude, reduced CV, and no change in PPR during the CP (20). These data demonstrate that plasticity at unitary FS→SP synapses undergoes a switch in sign at the transition between the pre-CP and the CP and suggest that this change in sign can account for the developmental change in the effects of VD at this synapse.

Both LTDi and LTPi Depend on GABABR Activation.

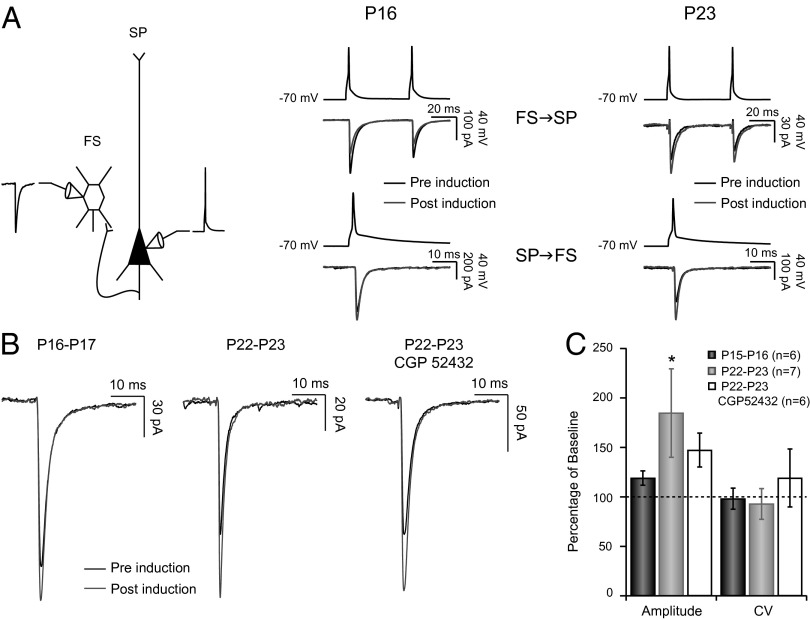

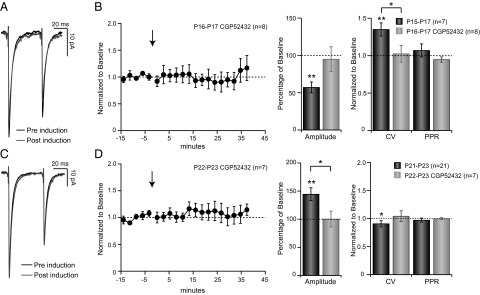

Our data above show that plasticity at FS→SP synapses flips sign at the opening of the CP. We wondered whether this might reflect developmental changes in the underlying signaling pathways that trigger plasticity at this synapse. The signaling pathways responsible for plasticity at neocortical L4 FS→SP synapses are not currently known; however, some forms of neocortical LTP of inhibition depend on GABABR signaling (26, 27), whereas some forms of neocortical LTD of inhibition depend on endocannabinoid signaling (26, 28). Here we asked whether L4 FS→SP plasticity is also dependent on GABABR signaling. In the presence of the GABABR antagonist CGP52432 (2 µM) the LTDi usually expressed at FS→SP synapses failed to develop, with both the change in amplitude and the change in CV prevented (Fig. 4A; n = 8; 95.04 ± 16.72% of baseline, P = 0.25, and 102.28 ± 11.21% of baseline, P = 0.84, respectively). Strikingly, preventing activation of GABABR during the CP also prevented LTPi from occurring (Fig. 4 C and D; n = 7) with no change in amplitude or CV postinduction (100.34 ± 14.02% of baseline and 104.46 ± 9.56% of baseline, P = 0.93 and Plower tail = Pupper tail = 0.53, respectively). Thus, plasticity at both ages is critically dependent on GABABR signaling. The effects of GABABR antagonism on basal transmission at this synapse were developmentally regulated: during the pre-CP, GABABR antagonism increased PPR (PPRPre-CP GABAB = 0.79 ± 0.03 vs. PPRPre-CP CTRL = 0.72, P = 0.012; nGABAB = 19; nCTRL = 48) and synaptic latency (LatencyPre-CP GABAB = 0.53 ± 0.03 vs. LatencyPre-CP CTRL = 0.43 ± 0.01; P = 0.006), whereas these parameters were unchanged at CP synapses (PPPR = 0.79 and PLatency = 0.25; nGABAB = 28; nCTRL = 46).

Fig. 4.

Both LTDi and LTPi are dependent on GABABR activation. (A) Average uIPSC traces obtained from baseline (black) and postinduction (gray) in presence of 2 µM CGP52432 at P16–P17. (B) (Left) uIPSC amplitude before and after induction in the presence of CGP52432 at P16–P17 (n = 8), (Center) magnitude of change for control (black) and CGP52432 (gray) following induction, and (Right) CV and PPR for both conditions following induction and normalized to baseline. (C) uIPSC amplitude before and after induction in the presence of 2 µm CGP52432 at P22–P23. (D) Same as for B but for induction at P21–23. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Plasticity at Reciprocal SP→FS Connections.

FS and SP neurons are often reciprocally connected. VD during the CP is known to increase the amplitude of both directions of this reciprocal connection (20), so that excitatory connections to FS cells and then inhibition back onto SP cells both increase. We wondered whether this coordinated regulation might be reflected at the level of plasticity of unitary connections, so that the same pairing of activity (high-frequency firing in the FS cell coupled to subthreshold depolarization in the SP neuron) might induce plasticity at both synapses simultaneously. To examine this, we assessed the strength of SP→FS synapses in the subset of experiments in which the pair was reciprocally connected. At P15–P16 (when FS→SP synapses express LTDi; Fig. 5A, Center Upper) the amplitude of the reciprocal connection was not significantly affected by this induction protocol (Fig. 5A, Center Lower, B, and C; n = 6; 119.03 ± 7.22% of baseline, P = 0.56). In contrast, during the CP (when FS→SP synapses express LTPi, Fig. 5A, Right Upper), the SP→FS synapse potentiated as well (Fig. 5A, Right Lower, B, and C; n = 7; 184.71 ± 44.69% of baseline, P = 0.031). Unlike potentiation at FS→SP synapses, this reciprocal potentiation was not accompanied by a change in CV (Fig. 5C). Further, SP→FS potentiation was not blocked by the GABABR antagonist CGP52432 (Fig. 5C; n = 6); although the degree of potentiation was slightly smaller in the presence of the antagonist, the difference between control potentiation and potentiation in the presence of the antagonist was not significant (P = 0.77). Thus, although these two forms of plasticity are induced simultaneously by the same induction protocol, the signaling pathways that underlie them are distinct. These data demonstrate that a second pronounced feature of the maturation of feedback inhibition at the transition to the CP is the acquisition of plasticity at SP→FS synapse.

Fig. 5.

Plasticity at reciprocal SP→FS synapses. (A) (Left) Representative scheme of the experimental condition. (Center) Example of the plasticity (and the lack thereof) at a reciprocal FS↔SP connection at P16 (black, preinduction; gray, postinduction). (Right) Example of LTPi obtained at a reciprocal FS↔SP connection at P23 (black, preinduction; gray, postinduction). (B) Plasticity at SP→FS synapses. (Left) Average unitary excitatory postsynaptic current (uEPSC) traces obtained from preinduction (black) and postinduction (gray) at P15–P16, (Center) average uEPSC traces obtained from preinduction (black) and postinduction (gray) at P22–P23, and (Right) average uEPSC traces obtained from preinduction (black) and postinduction (gray) at P22–23 in the presence of 2 µm CGP52432. (C) Degree of plasticity and change in CV at SP→FS connections at P15–P16 (black), P22–P23 (gray), and P22–P23 + CGP52432 (white). *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Long-term reconfiguration of inhibitory microcircuits is emerging as an important feature of experience-dependent development. We demonstrate here that the sign of long-term plasticity at unitary FS→SP connections in L4 of visual cortex is developmentally regulated and flips from depression to potentiation at the transition between the pre-CP and the CP. This transition mirrors the developmental switch in sign of the effects of VD at this same synapse. Further, we find a coordinated regulation of plasticity at reciprocally connected FS↔SP pairs, so that after CP onset both excitation onto FS cells and inhibition onto SP cells are potentiated by the same pairing protocol. These data suggest that an important feature of the transition to CP plasticity is the acquisition of reciprocal LTP within this specific feedback inhibitory microcircuit, which would serve to amplify feedback inhibition onto SP neurons.

Inhibitory GABAergic interneurons are highly diverse in their morphological and physiological properties (29, 30) and play many roles in microcircuit computation (31, 32), including balancing excitation and inhibition to sustain cortical network stability (33–36). This versatility is enabled in part through a diverse set of plasticity mechanisms that allow inhibition to be modulated by sensory experience (26, 37–40). Hebbian (LTP and LTD) and spike-timing–dependent forms of plasticity at inhibitory synapses have been broadly described in multiple brain areas and involve numerous induction and expression mechanisms (27, 37, 41–43). Although some forms of inhibitory plasticity are confined to particular developmental windows (44–46), this is a unique case in which the same induction protocol at a defined inhibitory synapse has been shown to induce opposite forms of plasticity at two different ages. This precise developmental timing suggests that maturation of inhibitory plasticity is an important feature of CP plasticity within L4.

Surprisingly, the developmental flip in sign of plasticity from LTDi to LTPi at the transition between the pre-CP and the CP was not associated with any major changes in the properties of unitary connections between FS and SP neurons in L4. During the same developmental window, global inhibitory synaptic transmission has been shown to progressively increase in strength to reach a steady state at the end of the CP (27, 28, 47). In most previous studies the strength of inhibition was assessed by activating a diverse population of inhibitory interneurons with extracellular stimulation, but in mice, uIPSCs from L4 FS→SP were observed to increase significantly between P12 and P19 (28), whereas we found no difference in amplitude between P15–P17 and P18–P20; this could represent a species difference or reflect a phase of maturation that occurs before P15. Because connection probability between FS and SP neurons increases developmentally (10), net inhibition from FS to SP neurons likely increases over this developmental window even though unitary connection strength does not change significantly. Nonetheless, our data make clear that the change in sign of plasticity at unitary connections is not correlated with developmental changes in unitary connection strength.

What could be the cellular mechanism underlying the change in sign of inhibitory plasticity that we observe? At excitatory synapses, initial synaptic strength, the subunit composition of NMDA receptors, and coupling of calcium to downstream signaling cascade have all been suggested to influence the sign of synaptic plasticity (48–50). As discussed above, the properties of basal transmission at FS→SP synapses change only subtly over the developmental window studied here, suggesting that major changes in GABA release or other such factors are unlikely to explain the switch in sign of plasticity. Additionally, the initial signaling events (GABA release and GABABR activation) necessary for plasticity induction remain the same. On the other hand, the effects of GABABR blockade on basal transmission at FS→SP did change developmentally, suggesting that either the localization or the signaling pathways activated by GABABR are developmentally regulated. At the moment, our data cannot distinguish between a requirement for presynaptic versus postsynaptic GABABR activation, so it remains possible that the locus of activation of these receptors changes developmentally. Taken together, these data suggest that the change in sign of plasticity at FS→SP synapses lies downstream of GABABR signaling and reflects a change in the coupling between GABABR activation and the effectors of synaptic plasticity.

During the CP, SP→FS plasticity can be induced by the same pairing protocol (FS firing coupled with mild SP depolarization) that induces plasticity at the reciprocal FS→SP connection. Unlike FS→SP plasticity, SP→FS plasticity does not require GABABR activation, indicating different underlying induction requirements. The expression mechanisms also differ because FS→SP plasticity is accompanied by changes in CV, whereas SP→FS plasticity is not, suggesting that this plasticity is expressed through a postsynaptic mechanism. Although the underlying signaling pathways mediating SP→FS plasticity are at the moment entirely unclear, it is possible that mild SP depolarization releases a plasticity factor (such as BDNF or an endocannabinoid) that acts in conjunction with calcium influx into FS cells to modify postsynaptic strength. This possibility remains speculative because we currently do not know the detailed activity requirements for induction of SP→FS plasticity, including whether it requires SP depolarization.

The effects of VD at FS→SP synapses change sign from depression to potentiation at the transition from pre-CP to CP, and there is evidence that LTPi underlies the VD-induced potentiation during the CP (20). Might LTDi underlie the VD-induced depression of this synapse during the pre-CP? Consistent with this possibility, we found that LTDi changes the strength and CV but not PPR of FS→SP synapses, the same constellation of effects reported previously for pre-CP VD (19). An alternative possibility is that VD during the pre-CP induces a homeostatic down-scaling of inhibitory transmission to compensate for the reduced sensory drive, through a distinct cellular mechanism (19, 51). Both LTDi and inhibitory scaling down would have the same overall effect of reducing inhibition and boosting circuit excitability, but unraveling which one drives the experience-dependent refinement of FS→SP circuits during the pre-CP will first require identifying the molecular underpinnings of both types of plasticity.

FS cells in V1m L4 receive direct thalamic drive (52, 53) and excitatory drive from SP neurons (19, 20). Consequently, they mediate both feedforward and feedback inhibition onto SP neurons. The net amount of feedback FS inhibition onto SP neurons will thus be affected by both FS→SP and SP→FS synaptic strength. A notable finding of this study is that plasticity at these reciprocal connections is regulated in parallel, so that both synapses acquire the ability to undergo LTP at the transition from the pre-CP to the CP. Thus, at the opening of the CP, specific patterns of activity within L4 can effectively potentiate feedback inhibition by coordinately boosting the strength of FS↔SP connections. This activity-dependent modulation of feedback inhibition is likely to play important roles both in the response to sensory deprivation (10, 19) and in the normal experience-dependent refinement of visual cortical circuitry.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Brain Slices.

Coronal brain slices (300 µm thick) containing the primary visual cortex (V1) from rats aged between P15 and P23 were cut on a vibratome (Leica VT1000S) in a standard ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF1; containing, in mM, 126 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, and 25 Dextrose). Slices were then transferred to a chamber filled with a modified ACSF for paired recordings (ACSF2; containing, in mM, 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 25 dextrose), oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2 at 35 °C for 15–20 min and subsequently at room temperature before use.

Whole-Cell Recordings.

Excitatory neurons (Star Pyramids) and Fast-Spiking GABAergic neurons in L4 of the monocular V1 (V1m) were visualized with a 40×/0.8 numerical aperture water immersion objective using differential interferance contrast contrast optics (Olympus BX50 or Olympus BX51). Quadruple simultaneous whole-cell patch clamp recordings in current and voltage clamp mode were acquired with either Axopatch 200B or Multiclamp 700B amplifiers (Molecular Devices). Patch-pipettes had resistances of 5–7 MΩ. The pipette intracellular solution for paired recordings contained (in mM) 20 KCl, 100 K-gluconate, 10 Hepes, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, and 10 Na-phosophocreatine. Biocytin (0.2%) was added to the intracellular solution for subsequent morphological identification. Electrophysiological data were low-pass Bessel filtered at 4–5 kHz and digitized at 10–20 kHz (National Instruments). Membrane potential measurements were not corrected for the liquid junction potential. Recordings were excluded from analysis if access resistance (Ra) was >25 MΩ, resting membrane potential (Vm) was >−60mV, or if these parameters or input resistance changed by more than 15%, 10%, or 20% (respectively) throughout the recording. All recordings were carried out at 35 °C, and slices were continually superfused with oxygenated ACSF. The cell types (SP or FS) were identified by firing pattern, by synaptic properties, and with post hoc biocytin staining to recover their anatomy.

Monosynaptic connections between FS and SP neurons were probed with a train of two or five well-timed action potentials (AP) at 20 Hz triggered in the presynaptic neuron while postsynaptic neurons were voltage clamped at −70mV. Mean traces were obtained by averaging 30–40 sweeps. The baseline was computed as an average across 5 ms before the current injection. The CV was computed as the SD divided by the mean amplitude for the first IPSC in the train. The PPR was calculated as the ratio of IPSC2/IPSC1 amplitude for each pair.

For plasticity experiments, presynaptic and postsynaptic cells were clamped at −70mV throughout the recording. Preinduction and postinduction synaptic properties at FS→SP synapses were assessed by a presynaptic train of two or five spikes at 20 Hz, repeated 40 and 120 times, respectively, at 0.05Hz, with the postsynaptic neurons either in current or in voltage clamp mode. Induction protocol was performed in current clamp and consisted of pairing presynaptic high-frequency firing (10 spikes, 50 Hz) with subthreshold postsynaptic depolarization, 20 times at 0.1 Hz, as previously described (20). Occasionally, this postsynaptic depolarization was sufficient to induce one or two postsynaptic spikes. To probe for effect of zolpidem on FS→SP connections, a baseline recording (40 sweeps) was first acquired in ACSF2, and then ACSF2 containing 0.2µM zolpidem was washed into the slice and connection strength was recorded again starting 5 min after wash-in for a period equivalent to the baseline. The average of 40 repetitions before and after zolpidem wash-in was compared.

Statistics.

Custom routines in Igor Pro (Wavemetrics Inc.) were used to analyze electrophysiological data and perform statistics. Data analyses are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistically significant differences between ages (P < 0.05) were assessed by performing a nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed with a post hoc Dunn–Holland–Wolfe test for multiple pair-wise comparisons. To evaluate the statistical significance for plasticity experiments, a Wilcoxon rank test for paired data (before and after induction) was performed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant EY014429 (to G.G.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J Physiol. 1970;206(2):419–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubel DH, Wiesel TN, LeVay S. Plasticity of ocular dominance columns in monkey striate cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1977;278(961):377–409. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1977.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274(5290):1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai NS, Cudmore RH, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Critical periods for experience-dependent synaptic scaling in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(8):783–789. doi: 10.1038/nn878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Fitzpatrick D, White LE. The development of direction selectivity in ferret visual cortex requires early visual experience. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(5):676–681. doi: 10.1038/nn1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SL, Trachtenberg JT. Experience-dependent binocular competition in the visual cortex begins at eye opening. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(3):370–375. doi: 10.1038/nn1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feller MB, Scanziani M. A precritical period for plasticity in visual cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15(1):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hensch TK. Critical period regulation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:549–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooks BM, Chen C. Critical periods in the visual system: Changing views for a model of experience-dependent plasticity. Neuron. 2007;56(2):312–326. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maffei A, Turrigiano G. The age of plasticity: Developmental regulation of synaptic plasticity in neocortical microcircuits. Prog Brain Res. 2008;169:211–223. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)00012-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagiolini M, et al. Specific GABAA circuits for visual cortical plasticity. Science. 2004;303(5664):1681–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.1091032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hensch TK. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(11):877–888. doi: 10.1038/nrn1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chattopadhyaya B, et al. Experience and activity-dependent maturation of perisomatic GABAergic innervation in primary visual cortex during a postnatal critical period. J Neurosci. 2004;24(43):9598–9611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1851-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chattopadhyaya B, et al. GAD67-mediated GABA synthesis and signaling regulate inhibitory synaptic innervation in the visual cortex. Neuron. 2007;54(6):889–903. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Cristo G, et al. Subcellular domain-restricted GABAergic innervation in primary visual cortex in the absence of sensory and thalamic inputs. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(11):1184–1186. doi: 10.1038/nn1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagiolini M, Hensch TK. Inhibitory threshold for critical-period activation in primary visual cortex. Nature. 2000;404(6774):183–186. doi: 10.1038/35004582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hensch TK, et al. Local GABA circuit control of experience-dependent plasticity in developing visual cortex. Science. 1998;282(5393):1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwai Y, Fagiolini M, Obata K, Hensch TK. Rapid critical period induction by tonic inhibition in visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23(17):6695–6702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06695.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maffei A, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Selective reconfiguration of layer 4 visual cortical circuitry by visual deprivation. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(12):1353–1359. doi: 10.1038/nn1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maffei A, Nataraj K, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Potentiation of cortical inhibition by visual deprivation. Nature. 2006;443(7107):81–84. doi: 10.1038/nature05079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunning DD, Hoover CL, Soltesz I, Smith MA, O’Dowd DK. GABA(A) receptor-mediated miniature postsynaptic currents and alpha-subunit expression in developing cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82(6):3286–3297. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritschy JM, Paysan J, Enna A, Mohler H. Switch in the expression of rat GABAA-receptor subtypes during postnatal development: An immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci. 1994;14(9):5302–5324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05302.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laurie DJ, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The distribution of thirteen GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. III. Embryonic and postnatal development. J Neurosci. 1992;12(11):4151–4172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04151.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trigo FF, Chat M, Marty A. Enhancement of GABA release through endogenous activation of axonal GABA(A) receptors in juvenile cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2007;27(46):12452–12463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3413-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malinow R, Tsien RW. Presynaptic enhancement shown by whole-cell recordings of long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices. Nature. 1990;346(6280):177–180. doi: 10.1038/346177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo PE, Chiu CQ, Carroll RC. Long-term plasticity at inhibitory synapses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21(2):328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Komatsu Y. GABAB receptors, monoamine receptors, and postsynaptic inositol trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release are involved in the induction of long-term potentiation at visual cortical inhibitory synapses. J Neurosci. 1996;16(20):6342–6352. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06342.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang B, Sohya K, Sarihi A, Yanagawa Y, Tsumoto T. Laminar-specific maturation of GABAergic transmission and susceptibility to visual deprivation are related to endocannabinoid sensitivity in mouse visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30(42):14261–14272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2979-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markram H, et al. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(10):793–807. doi: 10.1038/nrn1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ascoli GA, et al. Petilla Interneuron Nomenclature Group Petilla terminology: Nomenclature of features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(7):557–568. doi: 10.1038/nrn2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011;72(2):231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore CI, Carlen M, Knoblich U, Cardin JA. Neocortical interneurons: From diversity, strength. Cell. 2010;142(2):189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogels TP, Abbott LF. Gating multiple signals through detailed balance of excitation and inhibition in spiking networks. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(4):483–491. doi: 10.1038/nn.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogels TP, Sprekeler H, Zenke F, Clopath C, Gerstner W. Inhibitory plasticity balances excitation and inhibition in sensory pathways and memory networks. Science. 2011;334(6062):1569–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1211095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yizhar O, et al. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature. 2011;477(7363):171–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.House DR, Elstrott J, Koh E, Chung J, Feldman DE. Parallel regulation of feedforward inhibition and excitation during whisker map plasticity. Neuron. 2011;72(5):819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kullmann DM, Lamsa KP. LTP and LTD in cortical GABAergic interneurons: Emerging rules and roles. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(5):712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kullmann DM, Moreau AW, Bakiri Y, Nicholson E. Plasticity of inhibition. Neuron. 2012;75(6):951–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luscher B, Fuchs T, Kilpatrick CL. GABAA receptor trafficking-mediated plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Neuron. 2011;70(3):385–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McBain CJ, Kauer JA. Presynaptic plasticity: Targeted control of inhibitory networks. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19(3):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komatsu Y, Iwakiri M. Long-term modification of inhibitory synaptic transmission in developing visual cortex. Neuroreport. 1993;4(7):907–910. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199307000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nugent FS, Penick EC, Kauer JA. Opioids block long-term potentiation of inhibitory synapses. Nature. 2007;446(7139):1086–1090. doi: 10.1038/nature05726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brown TE, Chirila AM, Schrank BR, Kauer JA (2013) Loss of interneuron LTD and attenuated pyramidal cell LTP in Trpv1 and Trpv3 KO mice. Hippocampus 23(8):662–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Komatsu Y. Age-dependent long-term potentiation of inhibitory synaptic transmission in rat visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1994;14(11 Pt 1):6488–6499. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06488.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Long-lasting inhibitory synaptic depression is age- and calcium-dependent. J Neurosci. 2000;20(15):5820–5826. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05820.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLean HA, Caillard O, Ben-Ari Y, Gaiarsa JL. Bidirectional plasticity expressed by GABAergic synapses in the neonatal rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1996;496(Pt 2):471–477. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luhmann HJ, Prince DA. Postnatal maturation of the GABAergic system in rat neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65(2):247–263. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: An embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44(1):5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sáez I, Friedlander MJ. Plasticity between neuronal pairs in layer 4 of visual cortex varies with synapse state. J Neurosci. 2009;29(48):15286–15298. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2980-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Philpot BD, Cho KK, Bear MF. Obligatory role of NR2A for metaplasticity in visual cortex. Neuron. 2007;53(4):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turrigiano G. Too many cooks? Intrinsic and synaptic homeostatic mechanisms in cortical circuit refinement. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:89–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cruikshank SJ, Urabe H, Nurmikko AV, Connors BW. Pathway-specific feedforward circuits between thalamus and neocortex revealed by selective optical stimulation of axons. Neuron. 2010;65(2):230–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, Kloc M, Gu Y, Ge S, Maffei A. Layer-specific experience-dependent rewiring of thalamocortical circuits. J Neurosci. 2013;33(9):4181–4191. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4423-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]