Significance

Racial segregation in romantic networks is a robust and ubiquitous social phenomenon—but one we understand remarkably poorly. In this paper, I analyze a large network of interactions among users of a popular online dating site. First, I find that users from all racial backgrounds are equally likely or more likely to cross a racial boundary when reciprocating than when initiating romantic contact. Second, I find that certain subsets of users who receive—and reply to—a cross-race message initiate more new interracial exchanges in the short-term future than they would have otherwise. These findings illustrate an important mechanism whereby racial biases in assortative mating may be reduced temporarily by the actions of others.

Keywords: social networks, preemptive discrimination, OkCupid, assortative mating

Abstract

The racial segregation of romantic networks has been documented by social scientists for generations. However, because of limitations in available data, we still have a surprisingly basic idea of the extent to which this pattern is generated by actual interpersonal prejudice as opposed to structural constraints on meeting opportunities, how severe this prejudice is, and the circumstances under which it can be reduced. I analyzed a network of messages sent and received among 126,134 users of a popular online dating site over a 2.5-mo period. As in face-to-face interaction, online exchanges are structured heavily by race. Even when controlling for regional differences in meeting opportunities, site users—especially minority site users—disproportionately message other users from the same racial background. However, this high degree of self-segregation peaks at the first stage of contact. First, users from all racial backgrounds are equally likely or more likely to cross a racial boundary when reciprocating than when initiating romantic interest. Second, users who receive a cross-race message initiate more new interracial exchanges in the future than they would have otherwise. This effect varies by gender, racial background, and site experience; is specific to the racial background of the original sender; requires that the recipient replied to the original message; and diminishes after a week. In contrast to prior research on relationship outcomes, these findings shed light on the complex interactional dynamics that—under certain circumstances—may amplify the effects of racial boundary crossing and foster greater interracial mixing.

Race is a uniquely divisive characteristic of American social life. Unlike sexual orientation, it often is immediately visible. Unlike gender, it is innately unrelated to procreation, and so conflict between racial groups is unmitigated by domestic and/or sexual dependence between men and women. Also, unlike socioeconomic status, it is a characteristic we are born with but powerless to change. Aside from its nature, the repercussions of racial background also are distinctly powerful in scope: Its consequences span from economic stratification—in which almost all racial groups experience lower median family incomes and higher rates of unemployment and poverty than do whites (1, 2)—to spatial segregation—in which minorities are disproportionately likely to live in neighborhoods characterized by crime, disorder, and concentrated disadvantage (3, 4)—to the deep-seated interpersonal hostility that has tainted American race relations since the birth of this country (5, 6).

Social scientists have measured this hostility using a variety of methods. Many of these instruments, however, are biased by subjects’ desire not to appear prejudiced (5) as well as by the limits of conscious awareness (7). A common alternative is to infer the magnitude of racial prejudice from the patterning of social networks—in other words, the degree to which individuals affiliate with others who are racially similar and avoid those who are racially dissimilar. Scientists have examined this patterning across a wide variety of settings and relationships (8–10) and found that Americans’ preference for same-race alters exceeds their preference for similarity based on any other characteristic (11). This is true particularly for American romantic networks—in which two individuals are much more likely to marry, live together, date, and even “hook up” if they share the same racial background than if they do not (12–15).

Although we know that racial bias in assortative mating exists, we still know strikingly little about it. Most studies of romantic ties rely on marriage records—but as couples marry later (16) and divorce often (17), these data tell us less today than ever before. Data on romantic networks tend to focus on outcomes rather than interactions (12), which obscures the underlying processes responsible for generating observed patterns. (For instance, two individuals from the same racial background may date because they prefer to date each other or because no one else is willing to date them.) Finally, data on romantic partnerships rarely are accompanied by information on the opportunity structure from which they were selected. However, to pinpoint the degree of in-group preference/out-group exclusion accurately, it is essential to have data on the partnerships that formed as well as the partnerships that could have formed but did not (8, 9).

To overcome these limitations, I analyzed data on user interactions on a popular online dating site. These data have several advantages. First, unlike traditional datasets focused on marriage, these data focus on the very early expression of romantic interest—a stage in which most people participate and at which demographic characteristics such as race are particularly salient (because interpersonal chemistry is yet unknown). Second, exchanges are recorded digitally so we can watch them unfold in continuous time. Third, because the composition of site membership is known, it is relatively straightforward to disentangle preferences from opportunity constraints. Fourth, these data are unhindered by the limitations of self-report, given that they capture actual behaviors in a “natural” (if digital) environment. Finally, online dating is not just theoretically important and methodologically useful, it is increasingly consequential for the formation of long-term, offline relationships (18).

Data for these analyses include 126,134 users of the dating site OkCupid (www.okcupid.com) as well as all messages sent among these users over a 2.5-mo period (October to mid-December 2010). OkCupid advertises itself as a generalist dating Web site (as opposed to the many “niche” sites available online), and membership is completely free. All identifiers (e.g., photos, user IDs) and open-ended text (e.g., profile essays, message content) were stripped before I acquired the data. The above study sample consists of all site users who self-identified as single, straight,† living in the United States, and “looking for” short-term and/or long-term dating (as opposed to casual sex, long-distance pen pals, etc.). It also includes only users who self-identified with one of the five largest racial categories on the site—Asian, black, Indian, Hispanic/Latin, and white‡—and who joined the Web site between October 1 and November 30, 2010. The latter restriction is to prevent artificial truncation of exchanges; otherwise, a message sent on October 1 (or any other date) might equally plausibly represent the initiation of a new exchange as the continuation of a prior exchange that began before the window of available data (Study Population).

Because the length of user exchanges is difficult to interpret sans content (two users who stop communicating might equally plausibly have lost interest as taken their interaction offline), I focus only on the first message sent from A to B and, if applicable, B’s first reply. I also exclude all same-gender messages. Consequently, the resulting social network plausibly may be interpreted to reflect the expression and reciprocation of romantic interest. Importantly, the Web site does not limit interaction to matches it “recommends” but allows users to search the general site population on the basis of personalized criteria (e.g., racial background and geographic proximity). Further, insofar as the site does recommend matches to its users, it does so using a transparent algorithm that rates any two users’ compatibility on the basis of self-reported priorities. Strictly speaking, therefore, all recommendations are endogenous to users’ own expressed preferences, and overall patterns of interaction should reflect individual choices rather than the exogenous interference of the dating site (Site Description).

I report the results from two analyses of dating site users’ behavior. First, I examine the racial patterning of messages and responses, and the degree of in-group preference/out-group aversion characterizing each. Second, I estimate the causal effect of receiving a cross-race message on the quantity of cross-race exchanges one initiates in the future.

Results

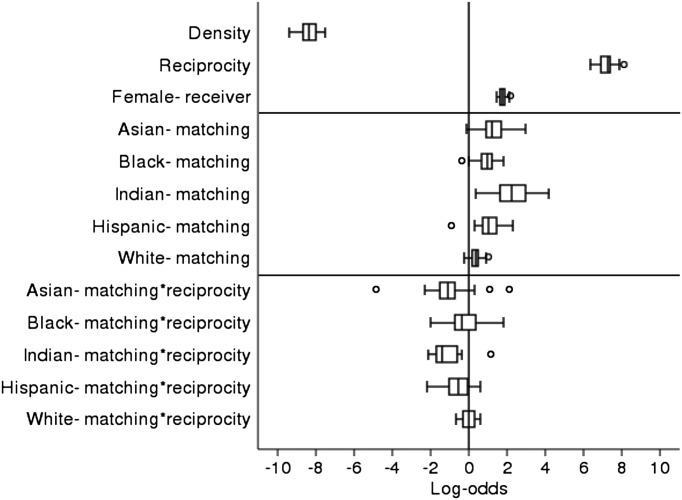

Fig. 1 provides a first look at inter- and intraracial contact rates among dating site users—and how these patterns vary from initiation messages to replies. Positive (negative) columns indicate that the given sender/receiver combination occurs more (less) frequently than chance would predict given the composition of site membership, and colored columns highlight same-race contact (Materials and Methods). Men and women from all racial backgrounds disproportionately initiate contact with other site users from the same racial background. Interestingly, however, the size of this preference decreases—in some cases, to the point of aversion—when we shift focus to replies. This difference is summarized in Fig. 1 C and F, which show that same-race preference is almost always greater for initiations than for replies (the sole exception is Indian men).§

Fig. 1.

Affiliation indices representing rates of inter- and intraracial contact among site users (n = 126,134). A and D represent patterns of initiations for men and women, respectively; B and E represent patterns of responses; and C and F represent the difference between the two. The racial background of the sender (receiver) appears across the width (depth) of the plot. Colored columns emphasize in-group behavior: green signifies a positive index (preference) and red signifies a negative index (aversion). A, Asian; B, black; H, Hispanic; I, Indian; W, white.

To move beyond this descriptive portrait, I used a statistical model. Exponential random graph (ERG) modeling is a sophisticated technique for understanding how patterns in social networks are generated (19). Specifically, these models can statistically disentangle the contribution of various possible reasons one user might message another, including distinguishing and directly comparing patterns of initiations with patterns of replies, while inherently controlling for the structural constraints of group size (Materials and Methods). To ensure that geographic distance is not conflated with social distance (20), I estimated a separate model for each two-digit ZIP code region and considered only intraregional messages.¶ Because racial minorities were absent from some regions, I also include only regions with more than 1,000 members represented in the sample. Time is suppressed in this analysis, al though with minimal ramifications for results (Methodological Details).

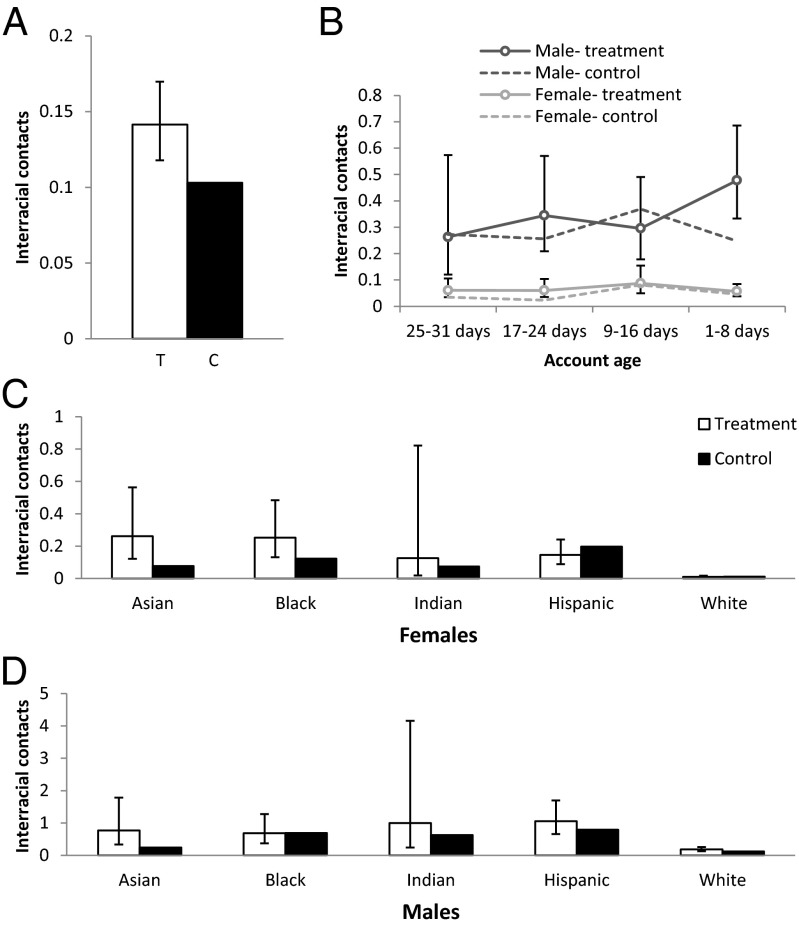

Fig. 2 summarizes parameter estimates across these models. Unsurprisingly, the baseline likelihood of any two users contacting each other (“density”) is extremely low; however, the log odds of B sending a message to A increase tremendously if A has contacted B first (“reciprocity”). Also unsurprising (to most heterosexual dating site users) is that men are much more likely to contact women than women are to contact men (“female-receiver”). Corresponding to Fig. 1, “matching” coefficients across all five racial categories are almost always positive, indicating a high degree of in-group preference net of opportunity structures, particularly for minority site users. Additionally, however, parameter estimates for the interaction of racial matching and reciprocity (“matching*reciprocity”) are predominantly negative for Indian, Asian, and Hispanic users, and roughly distributed around zero for white and black users. In other words, although site users are still generally more likely to respond to a same-race message than a cross-race message—given that matching coefficients tend to be slightly greater in absolute value than interaction term coefficients—this tendency is either equally pronounced (for white and black users) or less pronounced (for Indian, Asian, and Hispanic users) than it is for initiating contact. (For the full array of coefficients from all models and a direct comparison of the log odds of all possible messaging scenarios, see Methodological Details.)

Fig. 2.

Box plots of parameter estimates from ERG models of messages sent among site users (n = 102,540). I ran 44 independent models, one for each two-digit ZIP code region with more than 1,000 users in the sample; results from 43 of these models are presented here (one failed to converge) (Methodological Details). Plots follow the Tukey method: boxes represent quartiles, whiskers extend to the most extreme data point within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the edge of the box, and points represent outliers.

Next, I take a counterfactual approach to estimating the causal effect of receiving a cross-race message on the quantity of new cross-race exchanges one initiates in the future (Materials and Methods). In other words, for every “treatment” case of someone who received a cross-race message, I selected one or more “control” cases who were as similar to the treatment case as possible, but who did not receive a cross-race message. These cases serve as the counterfactual to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated (21), or the average quantity of new cross-race initiations “created” per person as a consequence of receiving a cross-race message from someone else. (Estimating the average treatment effect for the entire population requires a more stringent set of assumptions that likely do not apply here.) I matched treatment and control cases exactly according to gender, racial background, and two-digit ZIP code (thereby controlling for differences in opportunity structures as well as for regional differences in prejudice) and “coarsely” according to account age, quantity of previous initiations, and quantity of previous interracial initiations (22). For each individual, I measured control/matching variables during October, the treatment variable (whether or not a cross-race message was received) during the first week of November, and the outcome variable (the quantity of new cross-race exchanges initiated) during the second week of November. I required all individuals in this analysis to join the Web site in October and remain members of the site through the end of the treatment period, thereby (i) incorporating users with a diversity of membership lengths while (ii) maximizing the population who had the opportunity to receive the treatment.‖

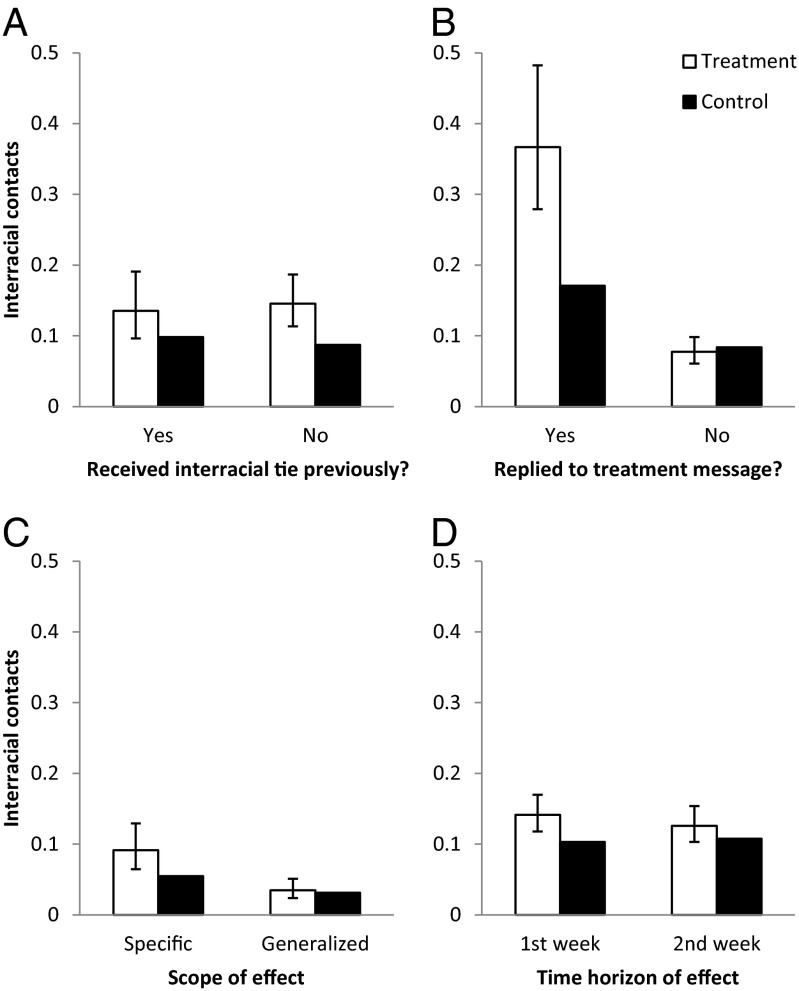

Among the 48,378 users eligible for this analysis, 4,263 (8.8%) received at least one interracial tie during the treatment period. Of these, 3,918 (91.9%) were matched successfully with at least one control case. Whereas individuals in the control condition initiated an average of 0.103 new interracial exchanges during the outcome period, individuals in the treatment condition initiated an average of 0.141 interracial exchanges, an increase of 37.3% (P < 0.001; Fig. 3A). The magnitude of this effect varies by account age, gender, and racial background (Fig. 3 B–D). Among women, the effect is strongest for those who joined the site 17–24 d (P < 0.001) or 25–31 d (P < 0.05) earlier. Among men, the effect is strongest for those who joined the site in the past 1–8 d (P < 0.001). The effect also is strongest for Asian women (who initiated 0.18 more interracial exchanges as a result of receiving an interracial message, an increase of 238%; P < 0.01), black women (106% increase; P < 0.05), Asian men (222% increase; P < 0.01), and white men (49% increase; P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Average quantity of interracial exchanges initiated among the treatment group (white bars) and matched controls (black bars). The difference between bars represents the average treatment effect on the treated, where 95% confidence intervals quantify the precision of this effect as estimated by negative binomial regression (confidence intervals appear asymmetrically because they are converted from a logarithmic scale). Results are presented separately for (A) the overall effect (n = 30,495), (B) comparisons by account age and gender, and (C and D) comparisons by gender and racial background. The relatively low baseline rate of interracial contact among white site users is not itself surprising, given that whites constitute the majority of the study sample and therefore have the fewest opportunities for interracial exchange. Results in their original logged form are presented in Methodological Details.

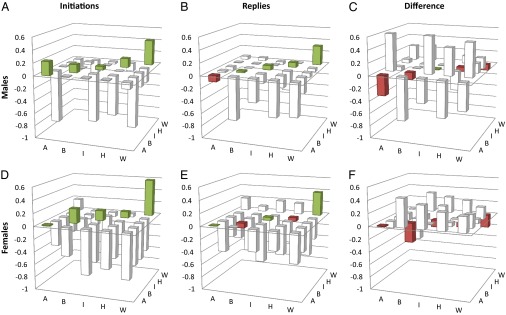

Fig. 4 unpacks these results even further. First, the effect of the treatment is strongest for those who have not previously been contacted by someone from a different racial background (P < 0.001 vs. P = 0.065; Fig. 4A). Second, the treatment is “effective” (in terms of producing future interracial contact) only when the recipient responds to the treatment message; such users initiate 115% more interracial exchanges during the outcome period compared with matched controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 4B).** Third, the effect of the treatment is specific to the racial background of the treatment sender: If a dating site user receives an interracial message from a member of racial group X, then that recipient is likely to initiate additional exchanges only with other members of group X in the future (P < 0.01; Fig. 4C). Finally, it is unlikely that the treatment effect is an artifact of unobserved differences between treatment and control groups. If this were the case, then we would expect the difference in outcomes between the two groups to persist over time. However, as early as 2 wk beyond the treatment period, the quantity of new interracial exchanges initiated by members of both groups becomes statistically indistinguishable (P = 0.125; Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Average treatment effect on the treated, presented separately by (A) whether the recipient of the treatment had received an interracial message previously, (B) whether the recipient of the treatment replied to the treatment message, (C) whether the outcome is defined as the quantity of interracial exchanges the recipient initiated with individuals from the same racial background as the treatment sender (“specific” effect) or the quantity of interracial exchanges the recipient initiated with individuals from a racial background different from that of the treatment sender (“generalized” effect), and (D) whether the outcome period is defined as the first or the second week following the treatment period. Confidence intervals are calculated using the same method as in Fig. 3. Results in their original logged form are presented in Methodological Details.

Discussion

Despite the centrality of romantic ties to day-to-day life, typical data on relationship outcomes obscure the dynamic interplay of attitudinal and relational forces that occurs at these relationships’ inception. I have shown that there is a “limit” to the degree of racial prejudice displayed by dating site users. First, racial boundaries are equally or more permeable when reciprocating than when initiating romantic contact; in fact, the larger the in-group bias for initiations (with Indian and Asian site users at one extreme and white site users at the other), the larger is the reversal of this bias for replies. Second, after receiving a cross-race message and sending a cross-race reply, many site users exhibit greater interracial openness in the short-term future, an effect that also is stronger for certain categories of minorities (e.g., Asian women, Asian men, and black women) than for whites. What explains these results?

One possibility, consistent with both sets of findings, is that dating site users engage in “preemptive discrimination.” In other words, part of the reason site users, and especially minority site users, do not express interest in individuals from a different racial background is because they anticipate—based on a lifetime of experiences with racism—that individuals from a different background will not be interested in them. In the event that this expectation is falsified by personal experience, however (i.e., the appearance of a cross-race suitor), the recipient not only is receptive to this overture, but begins considering future prospects she would not have otherwise considered (i.e., other site users from that same background). This would explain why the treatment effect is specific to the racial background of the sender, and also why its effects are relatively short in duration (because most subsequent suitors will again be from the same racial background as the recipient, reconfirming her initial expectations and restoring her original initiation patterns). Although a direct test of this hypothesis is not possible with these data,†† it is supported by supplementary analyses of profile views (Supplementary Analyses) as well as by research on indirect reciprocity, everyday discrimination, and social categorization. We know that people tend to “pay forward” both positive and negative experiences (23, 24) and that subtle displays of white racism toward minorities create “psychological tensions and cultural adaptations” that have a cyclical impact on minorities’ subsequent interaction with whites (25). On the other hand, researchers also have shown that the very process of racial encoding can be diminished, if not erased, in laboratory settings, suggesting that race, and hence racial prejudice, is a “volatile, dynamically updated cognitive variable” that can be “overwritten” by new circumstances (26).

Approaching mate choice through the lens of online dating inevitably confronts limitations. In general, examining digital traces of interaction patterns exchanges data accuracy, reliability, and scale for issues of privacy, data management, and interpretation (27, 28). The tradeoffs between observational and experimental data of any kind are well known, and causal claims using observational data are necessarily tentative (21). Additionally, it is an open empirical question whether racial dynamics on this site are generalizable to the myriad alternative dating sites on the internet (not to mention the many different ways prospective partners interact offline). I do not have data on the “depth” of online interaction or how subsequent romantic behavior is structured by the first two exchanges, and the findings described here are limited to heterosexual American users pursuing “dating,” with unclear implications for singles living in other countries, pursuing alternative ends, or identifying with alternative sexual orientations.

We know that certain types of people (29) with certain types of experiences (30) are more or less likely to cross racial boundaries. Much less common, however, is evidence demonstrating the subtle ways our own everyday actions may temporarily erode the prejudicial behavior of others. These results show that under certain circumstances, not only is the interracial expression of romantic interest more likely to be met with reciprocation than baseline rates of reciprocity and in-group preference would predict, but the consequences of this action are self-reinforcing, and might potentially set in motion a chain of future interracial contact among others.

Materials and Methods

I used three analytical approaches to produce the above results: one descriptive (affiliation indices) and two inferential (ERG modeling and coarsened exact matching). I describe these approaches below.

Affiliation Indices.

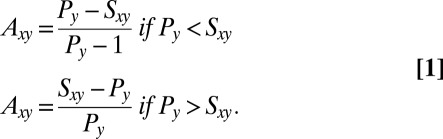

The descriptive index I use was developed by Heckathorn (31) in the context of respondent-driven sampling, but he notes it also may be used to describe patterns of association in a given social structure. If we define Sxy as the proportion of ties group X sends to group Y, and Py as the proportion of Y in the population, then the affiliation between any two groups X and Y is defined as

|

According to Eq. 1, the minimum value of Axy is −1, meaning that group X never forms ties with group Y (complete avoidance); the maximum value of Axy is 1, meaning that group X forms ties only with group Y (complete preference); and Axy is zero if group X forms ties with group Y only in proportion to group Y’s representation in the population, i.e., the degree of interracial mixing we would expect by chance. Both sets of affiliation indices (initiations and replies) were calculated conditional on the appropriate opportunity structure. In other words, indices of inter- and intraracial initiation for men (women) were calculated based on the racial composition of women (men) in the general population, whereas indices of male (female) replies were calculated based on the racial composition of female (male) initiations.

ERG Modeling.

Heckathorn’s index helps provide an overview of the gendered racial patterning of messages and replies, but it is limited in three ways. First, as a descriptive index, each subpopulation of interest (men vs. women; initiations vs. replies) must be examined separately, in contrast to a statistical model that can disentangle and directly compare the contribution of various mechanisms to observed patterns of interaction. Second, although the index has a straightforward interpretation (the proportion of time individuals from group X specifically seek out or avoid individuals from group Y), it does not consider that, because of differences in group size, individuals from some racial backgrounds (e.g., Indian site users) are encountered much less frequently—or are much “harder to find”—than individuals from other racial backgrounds (e.g., white site users). Consequently, indices are artificially inflated in proportion to the recipient’s group size. Third, for clarity of presentation, above I calculated indices only for the entire population of site membership. Not unlike studies of national intermarriage rates, this runs the risk that apparent social distance between groups may be a spurious consequence of geographic segregation (20) (e.g., individuals from group X may not actually prefer partners from group X to those from group Y, but rather more partners from group X are locally available).

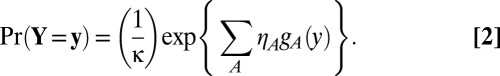

To complement this approach, therefore, I turned to a statistical model. In the rapidly advancing field of network methods, ERG models have received particular attention because of their breadth, flexibility, and ability to address the difficult computational problem of how networks are generated given the complex interdependencies between observations that characterize most network datasets (32). In ERG modeling, the possible ties among actors—here, messages among dating site users—are regarded as random variables. ERG models have the following general form:

|

“Dependence assumptions,” or the various possible reasons one user might contact another, determine the precise shape of the model. Specifically, the analyst posits any number of interpersonal micromechanisms that may explain observed patterns of interaction—for instance, the tendency for messages to be reciprocated (reciprocity) or the tendency for users from the same racial background to contact one another (racial matching). Each micromechanism corresponds to a particular network configuration (e.g., a “mutual” dyad consisting of both a message and a reply, or a message sent between two users from the same racial background, respectively). The presence of each configuration in the actual empirical network is quantified by gA(y) in Eq. 2, where ηA is a parameter measuring the importance of the given effect to the overall network structure. The summation is over all configurations A, and κ is a normalizing constant. Ultimately, therefore, the above expression has a straightforward and intuitive interpretation. It represents the probability of observing the empirical network that actually was observed as a function of the various underlying micromechanisms that might have produced it (19).

It may be helpful to think of this method as somewhat similar to logistic regression—except that instead of a dichotomous individual variable, the outcome of interest is a dichotomous dyadic variable indicating the presence or absence of a message between any two users in the sample. In fact, interpretation of model coefficients (at least for the effects presented here) is virtually identical to those from logistic regression: the log odds of any given message can be determined simply by adding the parameter estimates for all effects that describe that message. (So, for instance, to determine the log odds of an Asian male initiating contact with an Asian female, one adds the coefficients for the density effect, the female-receiver effect, and the Asian matching effect.) However, because of the dependence between ties explicitly represented by the various reciprocity effects, violating the independence among observations, these models cannot be estimated in closed form. Instead, I used Markov chain Monte Carlo maximum likelihood estimation, a simulation-based procedure that involves simulating distributions of networks on the basis of beginning parameter estimates, comparing these network simulations against the actual observed network data, refining parameter estimates accordingly, and repeating this process until the estimates reach an acceptable degree of stabilization (33). I estimated all models using ergm, the cornerstone of the statnet suite of packages for statistical network analysis (34). Additional details regarding model specification, parameter interpretation, and checks for model degeneracy are presented in Methodological Details.

Coarsened Exact Matching.

The fundamental problem in any attempt to estimate the causal effect of some treatment using observational data is that treatment and control cases are likely to differ in characteristics associated with the outcome of interest as well as the probability of receiving the treatment. Counterfactual approaches to causality attempt to address this concern (21, 35). In this framework, the analyst attempts to pair every case that has received the treatment to at least one identical (or approximately identical) control case that serves as the counterfactual outcome for the treatment case. The average treatment effect on the treated then may be estimated as the difference in average outcomes between treatment cases and their controls. (Generally, we do not have data available on how those in the control group would have behaved if they had instead received the treatment, and given that individuals who did not receive a cross-race message may have been deliberately avoided by interracial suitors for unobserved reasons, it is unwarranted to generalize to these individuals.)

Ideally, sufficient data are available that treatment cases can be matched exactly on all available covariates. In other words, the data are perfectly balanced. In practice, however, this rarely is possible because of curse-of-dimensionality issues (particularly with continuous covariates). The central idea behind coarsened exact matching, therefore, is to temporarily “coarsen” one or more variables into substantively meaningful groups; exactly match on these coarsened data, thereby partitioning the data into unique strata defined by every possible combination of covariates; and then retain only the original (uncoarsened) values of the matched data and drop any observation whose stratum does not contain at least one treated and one control unit. Once completed, these strata are the foundations for calculating the treatment effect; the only inferences necessary are those relatively close to the data, leading to less model dependence and reduced statistical bias, among other advantages (22).

I matched site users exactly based on gender, racial background, and two-digit ZIP code region, and coarsely based on overall quantity of initiation messages sent during the control period (dichotomized as one or more messages compared with no messages), quantity of interracial initiation messages sent during the control period (dichotomized as one or more interracial messages compared with no messages), and account length (divided into four approximately equal periods based on whether users joined in the first, second, third, or fourth quarter of October).‡‡ First, we may expect the greatest degree of variation in outcomes to be explained by users’ geographic region, which encompasses differences in opportunity structures for interracial contact as well as regional differences in average prejudice. Second, we may expect that users who initiated more exchanges of any kind in the past, especially interracial exchanges, would be particularly likely to initiate new interracial exchanges in the future. Third, we may expect that users who have been members of the site longer may be more or less likely to initiate exchanges of any kind and, therefore, more or less likely to initiate interracial exchanges. One problem is the possibility of unobserved differences between treatment and control groups; I address this possibility in Supplementary Analyses. I executed all matching using Stata’s cem command (22), then estimated the magnitude and statistical significance of the average treatment effect on the treated using negative binomial regression (because the outcome variable—quantity of interracial exchanges initiated—is a count variable with overdispersion).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I thank Felix Elwert for methodological guidance and Misiek Piskorski for collaboration in acquiring the dataset on which this research is based. I am also grateful for helpful conversations with Chana Teeger and Elizabeth Bruch; valuable feedback from the Social Psychology Brown Bag Series at the University of Southern California, the Family Working Group at the University of California, Los Angeles, the 2013 American Sociological Association session on Assortative Mating, and three anonymous reviewers; and encouragement from colleagues in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, San Diego, Kurt Gray, Kristen Lindquist, and Erin Everett. This work was supported by the Division of Research and Faculty Development at Harvard Business School.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

†My focus on heterosexuals is an important limitation of this study. However, given the reliance of prior research on marriage data, we know little about whether or how same-sex mate selection varies from heterosexual mate selection, such that it would be unwarranted to include both types of dynamics in the same analyses.

‡Racial categories are reproduced here as they appear on the site, which appears to be oriented on common use rather than logical consistency (e.g., “Asian” and “Indian” are treated as distinct categories).

§Other noteworthy gendered findings are that most men (except black men) are unlikely to initiate contact with black women (Fig. 1A), all men (including Asian men) are unlikely to reply to Asian women (Fig. 1B), and although women from all racial backgrounds tend to initiate contact with men from the same background (Fig. 1D), women from all racial backgrounds also disproportionately reply to white men (Fig. 1E).

¶Although 63.6% of initiation messages were sent between two users in the same two-digit ZIP code region, there are many more possible interregional pairs than intraregional ones; initiation messages between two users in the same region were 87.6 times more common than messages between two users in different regions.

‖I restricted measurement to the second week of November so that results would not be contaminated by Thanksgiving. Robustness checks suggest they were not (Supplementary Analyses).

**In fact, when analyses from Fig. 3 are limited to users who replied to the treatment message (as in Fig. 4B), the treatment effect is statistically significant for virtually all women, regardless of account age or racial background; men who joined the site in the past 1–8 d; Asian men; and Hispanic men. For results and interpretation, see Supplementary Analyses.

††To test this hypothesis, it is necessary to ascertain whether the above effects are specific to certain racial combinations—for instance, minorities responding to whites—rather than focusing solely on the racial background of the recipient. However, there are too few messages between certain combinations of minority users to address this possibility adequately with the methods used here.

‡‡I replicated all analyses while also controlling for the overall quantity of initiation messages received during the control period, i.e., each user’s prior “popularity.” In general, this increased rather than decreased the size of the treatment effect, and no result in Fig. 3 or 4 that previously was statistically significant ceased to be so.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1308501110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Waters MC, Eschbach K. Immigration and ethnic and racial inequality in the United States. Annu Rev Sociol. 1995;21:419–446. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris M, Western B. Inequality in earnings at the close of the twentieth century. Annu Rev Sociol. 1999;25:623–657. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charles CZ. The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annu Rev Sociol. 2003;29:167–207. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuman H, Steeh C, Bobo L, Krysan M. Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quillian L. New approaches to understanding racial prejudice and discrimination. Annu Rev Sociol. 2006;32:299–328. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanley DA, Sokol-Hessner P, Banaji MR, Phelps EA. Implicit race attitudes predict trustworthiness judgments and economic trust decisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(19):7710–7715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014345108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currarini S, Jackson MO, Pin P. Identifying the roles of race-based choice and chance in high school friendship network formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(11):4857–4861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911793107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wimmer A, Lewis K. Beyond and below racial homophily: ERG models of a friendship network documented on Facebook. AJS. 2010;116(2):583–642. doi: 10.1086/653658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry B. Friends for better or for worse: Interracial friendship in the United States as seen through wedding party photos. Demography. 2006;43(3):491–510. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:415–444. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalmijn M. Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annu Rev Sociol. 1998;24:395–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyner K, Kao G. Interracial relationships and the transition to adulthood. Am Sociol Rev. 2005;70(4):563–581. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackwell DL, Lichter DT. Homogamy among dating, cohabiting, and married couples. Sociol Q. 2004;45(4):719–737. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClintock EA. When does race matter? Race, sex, and dating at an elite university. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72(1):45–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoen R, Standish N. The retrenchment of marriage: Results from marital status life tables for the United States, 1995. Popul Dev Rev. 2001;27(3):553–563. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein JR. The leveling of divorce in the United States. Demography. 1999;36(3):409–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Gonzaga GC, Ogburn EL, VanderWeele TJ. Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(25):10135–10140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222447110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robins G, Pattison P, Kalish Y, Lusher D. An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Soc Networks. 2007;29(2):173–191. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris DR, Ono H. How many interracial marriages would there be if all groups were of equal size in all places? A new look at national estimates of interracial marriage. Soc Sci Res. 2005;34(1):236–251. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winship C, Morgan SL. The estimation of causal effects from observational data. Annu Rev Sociol. 1999;25:659–706. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackwell M, Iacus S, King G, Porro G. cem: Coarsened exact matching in Stata. Stata J. 2009;9(4):524–546. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1291–1298. doi: 10.1038/nature04131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray K, Ward AF, Norton MI. Paying it forward: Generalized reciprocity and the limits of generosity. J Exp Psychol Gen. doi: 10.1037/a0031047. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waters MC. Black Identities: West Indian Immigrant Dreams and American Realities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurzban R, Tooby J, Cosmides L. Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(26):15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazer D, et al. Social science. Computational social science. Science. 2009;323(5915):721–723. doi: 10.1126/science.1167742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garton L, Haythornthwaite C, Wellman B. Studying online social networks. J Comput Mediat Commun. 1997;3(1) Available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00062.x/full. Accessed May 4, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian Z. Breaking the racial barriers: Variations in interracial marriage between 1980 and 1990. Demography. 1997;34(2):263–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emerson MO, Kimbro RT, Yancey G. Contact theory extended: The effects of prior racial contact on current social ties. Soc Sci Q. 2002;83(3):745–761. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 2002;49(1):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snijders TAB. Statistical models for social networks. Annu Rev Sociol. 2011;37:131–153. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunter DR, Handcock MS. Inference in curved exponential family models for networks. J Comput Graph Statist. 2006;15(3):565–583. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Handcock MS, Hunter DR, Butts CT, Goodreau SM, Morris M. 2003. statnet: Software tools for the statistical modeling of network data. Available at http://statnetproject.org. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- 35.Morgan SL, Winship C. Counterfactuals and Causal Inference: Methods and Principles for Social Research. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.