Abstract

The immunogenicity and efficacy of influenza vaccination is markedly lower in the elderly. Granzyme B (GrzB), quantified in fresh cell lysates, has been suggested to be a marker of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response and a predictor of influenza illness among vaccinated older individuals. We have developed an influenza-specific GrzB ELISPOT assay using cryopreserved PBMCs. This method was tested on 106 healthy older subjects (age 50-74) at baseline (Day 0) and three additional time points post-vaccination (Day 3, Day 28, Day 75) with influenza A/H1N1-containing vaccine. No significant difference was seen in GrzB response between any of the time points, although influenza-specific GrzB response appears to be elevated at all post-vaccination time points. There was no correlation between GrzB response and hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers, indicating no relationship between the cytolytic activity and humoral antibody levels in this cohort. Additionally, a significant negative correlation between GrzB response and age was observed. These results reveal a reduction in influenza-specific GrzB response as one ages. In conclusion, we have developed and optimized an influenza-specific ELISPOT assay for use with frozen cells to quantify the CTL-specific serine protease GrzB, as a measure of cellular immunity after influenza vaccination.

Keywords: Granzyme B, cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), ELISPOT, influenza virus, cellular immunity, Granzymes, Killer Cells, Natural, Perforin, T-Lymphocytes, Cytotoxic, Enzyme-Linked Immunospot Assay, Influenza, Human, Viruses, Immunuity, Cellular

1. Introduction

Influenza outbreaks continue to plague all regions of the globe. The 2009 influenza A pandemic was caused by the H1N1 virus, the same subtype responsible for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed between 20 and 100 million people in 1918-1919 [1]. Influenza often leads to death in patients suffering from underlying illnesses such as congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and can also lead to additional illnesses including pneumonia and bacterial infection, which can result in death [2]. These complications are especially prevalent in the elderly population (adults 65+ years of age) [3].

As recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), annual vaccination is effective at reducing the global health burden associated with influenza [4]. The immune system responds to vaccination by producing influenza-specific antibodies. The hemagglutination inhibition assay (HAI) is used to quantify influenza-specific antibody levels by measuring the highest dilution of serum that prevents hemagglutination [5]. In addition to stimulating an adaptive humoral immune response, vaccination also primes the cellular immune response by promoting the formation of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) that are specific for influenza virus. Therefore, subsequent exposure to influenza elicits a secondary immune response against viral pathogens through cytolytic mechanisms.

Previous research indicates a dampening of this response in the elderly population due to immunosenescence [3, 6]. This is likely due to the decline in CTL response with replicative senescence as one ages, among other mechanisms [3]. Because of immunosenescence, questions arise regarding the efficacy of influenza vaccines in the elderly population [6].

To better understand the immunogenicity of influenza vaccines in the elderly, there must be an explicit, sensitive, quantitative assay to measure influenza-specific cell mediated immunity (CMI) in these individuals in addition to using HAI to measure humoral immunity. Previous research has suggested that granzyme B (GrzB) levels correlate with the cytolytic activity of CTLs responsible for the reduction and control of cytopathogenic viruses (e.g., influenza) [6]. When activated CTLs recognize virally infected host cells, the apoptotic pathway is induced through the cooperation of perforin and GrzB [7]. Perforin, a protein with structural and functional similarities to complement component 9, is polymerized in the presence of calcium, resulting in the formation of channels in the target cell lipid membrane [8]. These pores are utilized by GrzB, a serine protease, to pass into the cytoplasm of the target cell where it cleaves death substrates to effectuate cell death. This form of granule-mediated killing can be quantified, making it a candidate as a measure of the cellular immune response. In addition, GrzB (expressed primarily by CTLs, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells) is reported to have additional immune-related functions, such as degradation of viral proteins, receptor cleavage, cytokine-like functions, and immunosuppressive function [9].

There are significant variations in normal GrzB activity and levels between individuals. A sensitive and accurate assay is needed to quantify levels of GrzB as a measure of cellular immune response to vaccination [10]. Past research has demonstrated strong correlations between GrzB ELISPOT assays and the traditional chromium release assays, making ELISPOT an ideal substitute for more traditional techniques [11-14]. Additionally, the use of frozen, rather than fresh, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) allows for testing on large sample populations, which is a more practical concern for clinical trials. For these reasons, we have developed an influenza-specific GrzB ELISPOT assay using frozen PBMCs to measure CMI of older adults post influenza vaccination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study subjects

As previously reported, the sample population for this study included 106 eligible subjects who expected to be available for the duration of the study, ranging in age from 50 to 74 years [15]. All subjects underwent thorough review of their vaccination history and were in good health throughout the duration of this study. The 2010-2011 licensed trivalent influenza vaccine, containing the A/California/7/2009 H1N1-like, A/Perth/16/2009 H3N2-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like viral strains, was administered to all participants. Venipunctures were performed on these subjects once prior to vaccination (Baseline, Day 0) and three times within 75 days post-vaccination (Day 3, Day 28, and Day 75). All subjects provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mayo Clinic.

To verify the results of our study, the assay was also performed on 11 younger subjects ranging in age from 19-21 years. These subjects received the seasonal trivalent influenza vaccine for the 2005/2006 influenza season. These subjects have previously been described by Poland, et al. [16].

2.2. Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

PBMCs were isolated from each subject at each time point pre- and post-vaccination (Day 0, 3, 28 and 75) from 100 mL of whole blood using Cell Preparation Tube with Sodium Citrate (CPTTM) tubes, as previously described [15]. Cells were resuspended at a concentration of 1×107/mL in RPMI 1640 medium containing L-Glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Protide Pharmaceuticals, St. Paul, MN) and 20% fetal calf serum (FCS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), frozen overnight at − 80°C in Thermo Scientific freezing containers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to achieve an optimal rate of cooling. Cells were then transferred to liquid nitrogen for storage, as previously reported [15, 17].

2.3. Growth of influenza virus

The influenza A/California/7/2009/H1N1-like strain was obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta, GA). The virus was grown on embryonated chicken eggs, and the allantoic fluid containing the virus was harvested and titered by hemagglutination (HA) and 50% Tissue Culture Infectious Doses (TCID50) assay following infection by Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells (MDCK) using standard protocols [18-20].

2.4. Hemagglutination Inhibition (HAI) Assay

Influenza A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)-specific HAI titers were measured in subjects’ sera at each time point pre- and post-vaccination (Day 0, 3, 28 and 75) using a standard protocol, as described elsewhere [18-21]. Briefly, to eliminate non-specific inhibitors of hemagglutination, all sera were first treated with receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE, Vibrio cholerae filtrate, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), as previously reported [20]. Serial two-fold dilutions of the pretreated and inactivated sera (25 μl) were mixed with 4 HA units/25 μl of influenza virus and incubated for 30 min at room temperature to allow antigen-antibody binding. An equal volume (50 μl) of 0.5% turkey red blood cell suspension was then added to the mixture. HAI titers were determined after a 45-minute incubation on ice as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that completely inhibits hemagglutination [18-20].

2.5. Granzyme B ELISPOT Assay

Influenza-specific GrzB-positive cells were quantified in PBMC cultures using the BDTM Human Granzyme B ELISPOT kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol and as previously described [22]. Briefly, 96-well ELISPOT PVDF microplates were pre-coated with 5 μg/mL capture anti-GrzB antibody in sterile PBS, pH 7.2, incubated overnight at 4°C, and blocked (two hours at room temperature) with RPMI medium containing 10% FCS. Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed, counted and plated in ELISPOT plates at 2×105 cells/well in RPMI medium, containing 5% FCS, as previously reported [17]. Cells were mock-stimulated with RPMI 5% FCS (unstimulated wells in triplicate) or stimulated with influenza A/California/7/2009/H1N1-like virus at a multiplicity of infection/MOI of 0.5 for 24 hours incubation at 37°C, in 5 % CO2 (stimulated wells in triplicate). The optimal assay parameters were chosen based on testing three incubation periods after stimulation (18 h, 20 h, and 24 h) and three different MOIs (0.1, 0.2, and 0.5). With an MOI of 0.5 (24 h incubation), we achieved significantly higher influenza-specific GrzB response compared to lower MOIs in eight optimization samples (p<0.05, data not shown). Phytohemagglutinin/PHA (5 μg/mL, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used as a subject-specific positive control. After the incubation period, ELISPOT plates were processed following the manufacturer’s specifications using a biotinylated anti-GrzB antibody as a secondary antibody (2 μg/mL final concentration), streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase/HRP (dilution 1:100) and a tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)-H peroxidase substrate (Moss Inc., Pasadena, MD) for assay development (20 min. at room temperature), as previously reported [15, 17]. All assay plates were scanned and analyzed using the same pre-optimized counting parameters (including sensitivity, spot size, background and spot separation) on an ImmunoSpot® S6Macro696 Analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd., Cleveland, OH) using ImmunoSpot® version 5.1 software (Cellular Technology Ltd.). Quality control was performed by a single operator to eliminate spurious results [15, 17]. The results are presented as spot-forming counts (SFCs) per 2×105 cells as subjects’ medians (median of influenza virus-specific stimulated response, minus the median unstimulated response). The same assay parameters and reagents (including viral strain for stimulation), kits, scanning and counting parameters, and QC metrics were used for all subjects.

2.6. Statistical Methods

Influenza H1N1-specific GrzB response is calculated as the median of triplicate stimulated cells minus the median of triplicate unstimulated cells. Results are presented as percentiles of the distribution, box and whisker plots at each visit, and scatter plots by age. Differences in H1N1-specific GrzB response between visits were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Correlation between H1N1-specific GrzB response and age was evaluated using Spearman’s method. Intra-class correlation was assessed overall and by visit for the triplicate stimulated using Shrout and Fleiss’s method [23]. Analyses were conducted using the R statistical language software package version 2.15 and SAS® version 9.3 [24].

3. Results

3.1. Subject Demographics

Included in our cohort were 106 healthy subjects ranging from 50 to 74 years of age with a median age of 59.7 (interquartile range/IQR 55.3; 67.6). There were more females in this study (65, 61.3%) than males (41, 38.7%). The cohort primarily consisted of Caucasians (104, 98.1%), and the remainder of the subjects consisted of other races and ethnic groups (2, 1.9%) See Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic variables of the study population

| Variable | n=106 | n=11 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQRa) | 59.7 (55.3, 67.6) | 19.7 (19.0, 20.0) |

| Gender (n, %) | ||

| Female | 65 (61.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Male | 41 (38.7) | 11 (100.0) |

| Race (n, %) | ||

| Caucasians | 104 (98.1) | 11 (100.0) |

| Others | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) |

IQR, interquartile range

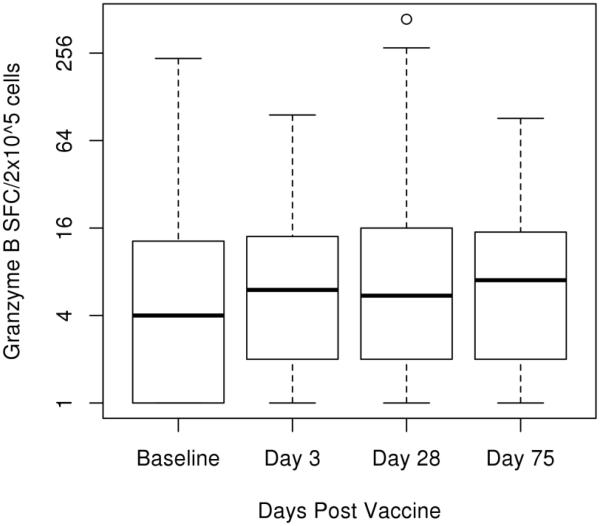

3.2. Granzyme B Response after Influenza Vaccination

We compared the median change in GrzB spot count (median of influenza stimulated cells in triplicate minus the median of unstimulated cells also in triplicate) between all time points to determine if influenza-induced GrzB response changed after vaccination. There was an observed increase in median spot count from baseline to all other time points (Days 3, 28, and 75 post-vaccination) (Figure 1) (Table 2), although these differences were not statistically significant (Table 3). The overall median PHA (positive control) response for our cohort was 1105 SFCs per 2×105 cells (IQR 501, 2000). The overall intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) comparing multiple observations per subject on one day was calculated to be 0.80 with a confidence interval of 0.78-0.82. The ICC for each visit (Baseline, Day 3, Day 28, and Day 75) ranged from 0.60-0.97.

Fig. 1.

Measure of Granzyme B response via ELISPOT assay. Frozen PBMCs were thawed, cultured, and stimulated with influenza A/H1N1 virus at 4 different time points pre- and post-vaccination. Median spot count (median stimulated minus median unstimulated), 25% percentile, and 75% percentile are plotted for each time point as spot forming cells (SFC) per 2×105 PBMCs. Minimum and maximum data points are included in the plot, as well as potential outliers. Differences between post-vaccination time points and baseline are as follows: Day 3 p-value 0.243, Day 28 p-value 0.099, and Day 75 p-value 0.057.

Table 2.

Distribution of Granzyme-B response over time

| Variable | Minimum | 25th% | Median* | 75th% | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 12.75 | 235.00 |

| Day 3 | −1.00 | 2.00 | 6.00 | 14.00 | 96.00 |

| Day 28 | −3.00 | 2.00 | 5.50 | 16.00 | 438.00 |

| Day 75 | −1.00 | 2.00 | 7.00 | 15.00 | 91.00 |

Median of the stimulated samples – median of the unstimulated samples (n=106)

Table 3.

Measures of Significance in Time point Variation of Granzyme B Spot Count

| P-value* | |

|---|---|

| Day 0 vs Day 3 | 0.243 |

| Day 0 vs Day 28 | 0.099 |

| Day 0 vs Day 75 | 0.057 |

| Day 3 vs Day 28 | 0.915 |

| Day 3 vs Day 75 | 0.604 |

| Day 28 vs Day 75 | 0.853 |

Wilcoxon signed rank test

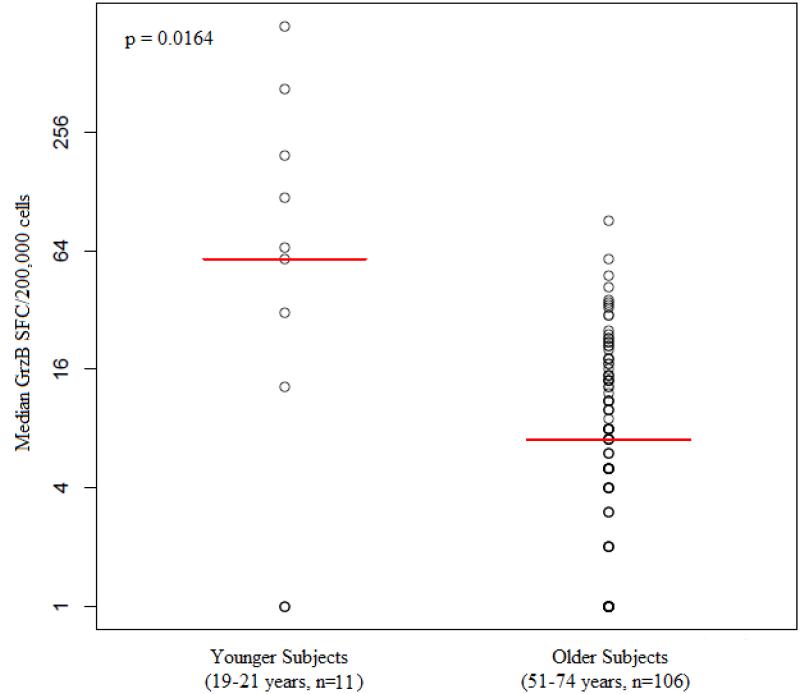

In addition, we compared the influenza-specific GrzB response of the cohort at Day 75 to that of a younger group of subjects (age 19-21 years, n=11). There was a significantly greater GrzB response in the younger subjects than the older cohort (p=0.016) (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of GrzB response between age groups: The median GrzB response of 11 younger subjects was compared to the median GrzB response of 106 older subjects at Day 75 (p value 0.0164).

3.3. Association between Granzyme B Levels and Hemagglutination Inhibition Titers

We also assessed humoral immunity in this cohort by quantifying HAI titers in addition to measuring cellular immune responses to influenza virus. For each subject, we compared HAI titers to GrzB response at each time point (Day 0, Day 3, Day 28, and Day 75). Statistical analysis shows no significant correlation between GrzB response and HAI at any of the time points. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation between Granzyme B response and HAI titers

| Spearman (r) | P-Value (p) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.10 | 0.332 |

| Day 3 | 0.05 | 0.636 |

| Day28 | 0.02 | 0.835 |

| Day 75 | −0.01 | 0.914 |

The median HAI titer at Day 0 was 1:80, whereas at Day 28, it was 1:320. The p-value comparing HAI titers from Day 0 to Day 28 is 6.92 × 10-12.

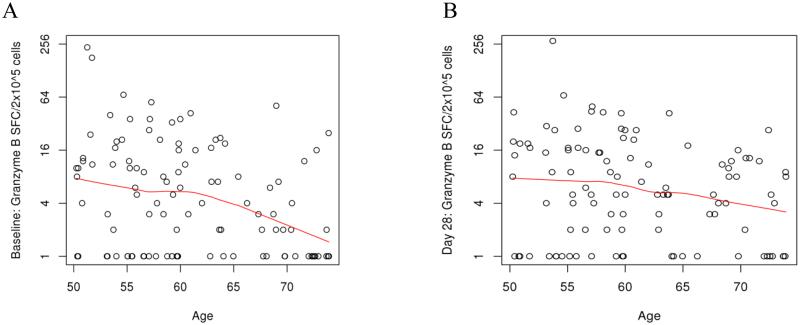

3.4. Association between Granzyme B Levels and Age

To understand the effect of immunosenescence on CTL activity, we also compared GrzB response at all time points to age. Significant negative correlations were seen at Day 0 (Spearman coefficient of -0.264, p-value 0.007) and at Day 28 (Spearman coefficient -0.21, p-value 0.032) for this cohort (Figure 2) (Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Correlations between GrzB response and Age: A (correlation between GrzB response at baseline and age, p value 0.007) and B (correlation between GrzB response at Day 28 and age, p value 0.032)

Table 5.

Correlation between Grazyme B response and age

| Spearman (r) |

P-Value (p) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | −0.26 | 0.007 |

| Day 3 | −0.09 | 0.36 |

| Day 28 | −0.21 | 0.032 |

| Day 75 | −0.02 | 0.846 |

4. Discussion

The development of an influenza-specific measure of CMI is critical to assess the ability to combat influenza infection post-vaccination. We developed an influenza-specific GrzB ELISPOT assay using cryopreserved PBMCs that would be an easy and efficient way to assess virus-specific GrzB response in large population-based studies and is applicable for testing large numbers of previously collected and stored samples [14, 25]. To the best of our knowledge, an ELISPOT-based Granzyme B assay has never been applied to assess influenza specific cellular immunity and CTL response using cryopreserved PBMCs. GrzB is a cytotoxic lymphocyte-associated serine esterase that is primarily produced by activated CD8+ CTLs and NK cells. This method measures the frequencies of GrzB-positive cells after influenza virus stimulation and offers a valuable alternative or addition to other assays evaluating cell-mediated antiviral immunity.

Traditionally, several methods have been used to measure GrzB response. Chromium release assays, used to measure cytolytic activity of CTLs, require high cell concentrations and use radioactive materials, so high throughput can be difficult [14]. Preparation of a chromium release assay is complex, and results yield a low signal-to-noise ratio, causing high variation in replicates. In addition, the use of radioactive materials can pose health hazards. The ASPase activity of GrzB is measured using the hydrolysis of the GrzB substrate tert-butyloxycarbonyl-Ala-Ala-Asp-thiobenzyl ester, and, therefore, is another GrzB-based assay of CMI [25]. Although tedious, this method used to quantify GrzB production/concentration in cell lysates has been effective at measuring CTL response in younger subjects, but it requires the initial use of fresh cells and thus is difficult to implement in larger studies. The method described by Gijzen, et al. uses frozen PBMCs and also measures GrzB production in cell lysates, but has been used only for a limited number of samples (two donors under three different conditions). Our assay is adapted to a commercially available ELISPOT kit and provides an easy, rapid, and high-throughput alternative to these GrzB assays [26]. However, compared to the ASPase activity assay described by McElhaney, et al. [25], we were not able to see a statistically significant difference in GrzB response post-influenza vaccination, but observed only a trend using the assay method we developed and used. This difference could be attributed to the type of PBMCs used and the age of the subjects in the study. McElhaney’s method to measure GrzB response utilized fresh PBMCs for influenza virus stimulation, as opposed to the frozen PBMCs we used in our study. Additionally, the study conducted by McElhaney, et al. included young adults as subjects, and if CMI does, indeed, decline with age, it is expected that a study using younger subjects would yield significant results [25]. This was verified in our study, as the median GrzB response of the older subjects at Day 75 was significantly lower than that of the younger subjects. This leads us to conclude that the lack of significant response in the older cohort was due to age, not to assay ineffectiveness, as the same assay parameters and controls were used in both sets of subjects.

It is important to note that a four-fold increase in HAI titers was observed from Day 0 to Day 28 with a significant p-value. This indicates that the subjects experienced a protective increase in humoral immune response. However, our study did not find a correlation between antibody titers, as measured by HAI assay, and cellular GrzB response. Particularly important is the observed negative correlation between age and the GrzB response at Day 28 (p=0.032), which further strengthens our conclusion that the lack of statistically significant rise in influenza-specific CMI post-vaccination and the relatively low CTL response is likely due to the age of the study subjects. Influenza-specific GrzB response cumulatively reflects the influenza vaccine-stimulated adaptive CTL response and the CTL memory response due to previous exposures to influenza and influenza vaccines. Reports from the literature indicate that the memory CTL response to influenza A can be directed against both highly conserved and variable CTL epitopes on a variety of viral proteins (including the hemagglutinin, neuraminidase, nucleoprotein, matrix protein, nonstructureal protein 1, polymerases PB1 and PB2 [27, 28]. In addition, it has been noted, that memory CTLs, established in pandemic H1N1 influenza virus-naïve individuals by seasonal influenza immunization, cross-react against pandemic H1N1 influenza virus [29], a finding that is in concert with our assay results for the younger cohort of subjects. Thus, our findings support the conclusion that the lack of significant flu-specific CMI response in our older cohort of subjects was due to their age rather than the effectiveness of the described assay. These findings are consistent with previously published data, demonstrating suboptimal influenza-specific CTL responses in older individuals [6, 30]. Observations have shown higher protection against H1N1 virus in the elderly than in younger adults despite their lower antibody levels, likely due to previous exposure to H1 viral subtypes [3]. Conversely, comparable antibody levels for H3N2 virus have been measured between young adults and older adults, although the elderly are not as well protected against infection [3]. Because influenza vaccination is less effective in older individuals and there is not a correlation between HAI and GrzB response, insufficient influenza protection may be the result of age-related changes primarily in the cellular immune function rather than the humoral immune function. This theory is consistent with the findings from our study.

Our study cohort consisted of older individuals, ages 50-74. Previous research suggests that CTLs are greatly affected as a result of replicative senescence in aging individuals [3]. Specifically, CTLs experience proliferative defects after prolonged replication [31]. Replicative senescence could also result in defective CTL function. Thus, studying only older subjects may explain why we observed a trend rather than statistically significant changes in GrzB response after vaccination using the influenza-specific GrzB ELISPOT assay we proposed. In addition, the overall intra-class correlation coefficient (0.80) suggests good assay reproducibility within a subject and are comparable to other ELISPOT-based assays [32-34].

As well as subject age, several other factors may account for the results of this study. Alternative assays used to measure GrzB response utilize fresh PBMC [25]. In our study, frozen PBMCs were used to create an assay applicable to large population-based studies. The response of PBMCs, including CTLs, can markedly decrease after thawing from cryopreservation [35]. Specifically, a decreased proliferative response to influenza virus was observed in CTLs [36]. Therefore, the cryopreservation of the PBMC samples in the study may have affected GrzB response levels both at baseline and post-vaccination.

There are other strengths and limitations to this study. Using a GrzB ELISPOT to detect influenza-specific cellular response to infection is an attractive alternative to traditional methods as it is capable of quantifying cellular immune response for larger cohorts [35]. Data from the literature suggest that the amount of GrzB expressed per CTL may be of importance for the influenza-specific cellular immunity, which our assay is unable to adequately measure [3, 37]. The small size of our study cohort may have resulted in limited data for statistical analysis. To combat this issue in the future, this assay should be applied to a larger sample size. The assay should also be applied to a younger cohort of subjects to determine whether subject age affects the GrzB response, and how such data compare to our older cohort. Lastly, the use of fresh PBMCs or cell types (CD8+ CTLs to attribute changes in GrzB response to changes in adaptive CMI, or NK cells) would be ideal in smaller studies, but is not usually feasible in large population-based studies.

In conclusion, our report outlines the need for proper assessment of influenza vaccine-induced CMI in the elderly. We have discussed the limitations of using only antibody titers as a correlate of protection, justifying the need for a measure of CMI. Our results show a negative correlation between influenza-specific GrzB response and age, indicating a decline in CTL activity with age concomitant with increasing susceptibility to influenza and its complications. Using CMI as a correlate of protection may be beneficial when examining the response to influenza vaccine in the elderly. Therefore, we have designed an alternative method for measuring cellular response to influenza vaccination using cryopreserved cells (rather than fresh cells) by measuring influenza-specific GrzB response with ELISPOT technology, which is more feasible for large population-based studies.

Acknowledgements

We thank the individuals who participated in this study. We thank Matt Taylor and Dr. Sarah White of the Mayo Clinic Vaccine Research Group for performing the ELISPOT assay. We thank Diane Grill for her contribution to the statistical analysis. We thank Caroline Vitse for her assistance with this manuscript. This work was supported by the NIH U01 AI089859. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Poland is the chair of a Safety Evaluation Committee for novel investigational vaccine trials being conducted by Merck Research Laboratories. Dr. Poland offers consultative advice on vaccine development to Merck & Co. Inc., CSL Biotherapies, Avianax, Sanofi Pasteur, Dynavax, Novartis Vaccines and Therapeutics, PAXVAX Inc., and Emergent Biosolutions. These activities have been reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board and are conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest policies. This research has been reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board and was conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest policies.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, et al. Estimation of potential global pandemic influenza mortality on the basis of vital registry data from the 1918-20 pandemic: a quantitative analysis. Lancet. 2006;368(9554):2211–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Small CL, et al. Influenza infection leads to increased susceptibility to subsequent bacterial superinfection by impairing NK cell responses in the lung. Journal of immunology. 2010;184(4):2048–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElhaney JE. Influenza vaccine responses in older adults. Ageing research reviews. 2011;10(3):379–88. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)--United States, 2012-13 influenza season. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2012;61(32):613–8. MMWR. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meijer A, et al. Measurement of antibodies to avian influenza virus A(H7N7) in humans by hemagglutination inhibition test. Journal of virological methods. 2006;132(1-2):113–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McElhaney JE, et al. Granzyme B: Correlates with protection and enhanced CTL response to influenza vaccination in older adults. Vaccine. 2009;27(18):2418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trapani JA, Smyth MJ. Functional significance of the perforin/granzyme cell death pathway. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2002;2(10):735–47. doi: 10.1038/nri911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shresta S, et al. How do cytotoxic lymphocytes kill their targets? Current opinion in immunology. 1998;10(5):581–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jahrsdorfer B, et al. Granzyme B produced by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells suppresses T-cell expansion. Blood. 2010;115(6):1156–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karulin AY, et al. Single-cytokine-producing CD4 memory cells predominate in type 1 and type 2 immunity. Journal of immunology. 2000;164(4):1862–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bleackley RC, et al. The isolation and characterization of a family of serine protease genes expressed in activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunological reviews. 1988;103:5–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1988.tb00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doherty PC, Christensen JP. Accessing complexity: the dynamics of virus-specific T cell responses. Annual review of immunology. 2000;18:561–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell JH, Ley TJ. Lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. Annual review of immunology. 2002;20:323–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100201.131730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rininsland FH, et al. Granzyme B ELISPOT assay for ex vivo measurements of T cell immunity. Journal of immunological methods. 2000;240(1-2):143–55. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umlauf BJ, et al. Associations between demographic variables and multiple measles-specific innate and cell-mediated immune responses after measles vaccination. Viral immunology. 2012;25(1):29–36. doi: 10.1089/vim.2011.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM. Immunogenetics of seasonal influenza vaccine response. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 4):D35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umlauf BJ, et al. Detection of vaccinia virus-specific IFNgamma and IL-10 secretion from human PBMCs and CD8(+) T cells by ELISPOT. Methods in molecular biology. 2012;792:199–218. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-325-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster R, Cox N, Stohr K. WHO Manual On Animal Influenza Diagnosis and Surveillance. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. pp. 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network . Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance of influenza. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. pp. 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S, et al. Hemagglutinin (HA) proteins from H1 and H3 serotypes of influenza A viruses require different antigen designs for the induction of optimal protective antibody responses as studied by codon-optimized HA DNA vaccines. Journal of virology. 2006;80(23):11628–37. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01065-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ovsyannikova IG. Turkey versus Guinea Pig Red Blood Cells: Hemagglutination Differences Alter HAI Responses against Influenza A/H1N1. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Manigold T, et al. Highly differentiated, resting gn-specific memory CD8+ T cells persist years after infection by andes hantavirus. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6(2):e1000779. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological bulletin. 1979;86(2):420–8. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.R Core Team . R: A Language and Envrionment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McElhaney JE, et al. The cell-mediated cytotoxic response to influenza vaccination using an assay for granzyme B activity. Journal of immunological methods. 1996;190(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gijzen K, et al. Standardization and validation of assays determining cellular immune responses against influenza. Vaccine. 2010;28(19):3416–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimmelzwaan GF, et al. Influenza virus CTL epitopes, remarkably conserved and remarkably variable. Vaccine. 2009;27(45):6363–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jameson J, Cruz J, Ennis FA. Human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte repertoire to influenza A viruses. Journal of virology. 1998;72(11):8682–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8682-8689.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu W, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes established by seasonal human influenza cross-react against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. Journal of virology. 2010;84(13):6527–35. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00519-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McElhaney JE, et al. Responses to influenza vaccination in different T-cell subsets: a comparison of healthy young and older adults. Vaccine. 1998;16(18):1742–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brenchley JM, et al. Expression of CD57 defines replicative senescence and antigen-induced apoptotic death of CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2003;101(7):2711–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartko JJ. The intraclass correlation coefficient as a measure of reliability. Psychological reports. 1966;19(1):3–11. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1966.19.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Germinario RJ, Waller JR. Transport of pantothenic acid in Lactobacillus plantarum. Canadian journal of microbiology. 1977;23(7):922–30. doi: 10.1139/m77-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis G. Polymorphism and selection in Cochilicella acuta. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. 1977;276(949):399–451. Series B, Biological sciences. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slota M, et al. ELISpot for measuring human immune responses to vaccines. Expert review of vaccines. 2011;10(3):299–306. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costantini A, et al. Effects of cryopreservation on lymphocyte immunophenotype and function. Journal of immunological methods. 2003;278(1-2):145–55. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boon AC, et al. Influenza A virus specific T cell immunity in humans during aging. Virology. 2002;299(1):100–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]