Abstract

Oral biofilms can degrade the components in dental resin-based composite restorations, thus compromising marginal integrity and leading to secondary caries. In this study, we investigated the mechanical integrity of the dentin-composite interface challenged with multi-species oral biofilms. While most studies used single-species biofilms, we used a more realistic, diverse biofilm model produced directly from plaques collected from donors with a history of early childhood caries. Dentin–composite disks were made using bovine incisor roots filled with Z100™ or Filtek™ LS (3M ESPE). The disks were incubated for 72hr in paired CDC biofilm reactors, using a previously published protocol. One reactor was pulsed with sucrose, and the other was not. A sterile saliva-only control group was run with sucrose pulsing. The disks were fractured under diametral compression to evaluate their interfacial bond strength. Surface deformation of the disks was mapped using digital image correlation (DIC) to ascertain fracture origin. Fracture surfaces were examined using SEM/EDS to assess demineralization and interfacial degradation. Dentin demineralization was greater under sucrose-pulsed biofilms, as the pH dropped below 5.5 during pulsing, with LS and Z100 specimens suffering similar degrees of surface mineral loss. Biofilm growth with sucrose pulsing also caused preferential degradation of the composite-dentin interface, depending on the composite/adhesive system used. Specifically, Z100 specimens showed greater bond strength reduction and more frequent cohesive failure in the adhesive layer. This was attributed to the inferior dentin coverage by Z100 adhesive which possibly led to a higher level of chemical and enzymatic degradation. The results suggested that factors other than dentin demineralization were also responsible for interfacial degradation. We have thus developed a clinically relevant in vitro biofilm model which would allow us to effectively assess the degradation of the dentin-composite interface subjected to multi-species biofilm challenge.

Keywords: multi-species biofilm, dental restoration, resin composite, degradation, bond strength, interface

Introduction

The use of resin based dental composites and the associated dentin/enamel bonding adhesives for restoring damaged or decayed teeth have increased significantly in recent years. In 2005, around 77 million composite restorations were placed in the United States, as opposed to 52 million amalgam restorations [1]. However, despite its superior aesthetics, low toxicity and ease of handling, composite restorations have higher failure rates and more recurrent caries, requiring as a result more frequent replacement than amalgam restorations [2-5]. There is a high likelihood that breakdown of the tooth-composite interface will take place at some point of the restoration's lifetime due to mechanical fatigue caused by mastication. For composite restorations with a high level of shrinkage stress induced by polymerization of the resin matrix, interfacial debonding between the composite and tooth is expected to occur during curing, leading to an early failure. Once interfacial breakdown has taken place, cariogenic bacteria within the oral cavity can invade through the resulting gaps and colonize the subsurface tooth tissues to initiate recurrent caries. Clinically, 80% to 90% of secondary caries was located at the gingival margins of Class II through V restorations, irrespective of the restorative material employed [6, 7]; and progression of caries occurs faster in dentin than in enamel. This is because the biofilms grown in these regions are better protected from hygienic procedures.

Oral biofilms are polymicrobial complexes composed of dozens to hundreds of different species [8, 9], and under certain environmental conditions play a critical role in the progression of dental diseases, such as dental caries [8]. The fermentable carbohydrates that form part of our food intake are metabolized to polysaccharides by microorganisms from dental plaque. Through nano/micro-leakage, the acids and enzymes produced from the metabolism can demineralize the underlying dental tissues and/or degrade the resin composite and adhesive of a restoration [10]. A question of great interest is whether oral biofilms can accelerate the mechanical breakdown of the tooth-composite interface mentioned above by actively degrading the interfacial bond strength, leading to secondary caries.

Oral biofilm models of single-species or defined species consortia are often used in in vitro experiments to study the effects of oral biofilms on different substrates. However, such simple models may not be adequate to simulate the complex actions of natural, multi-species oral biofilms on dental restorative materials. Several studies have demonstrated that stable microcosm oral biofilms can be produced from human plaque samples to study microbial effects on the properties of restorative materials [11, 12] or the generation and progression of secondary caries [11-14]. In a previous study, we used a CDC biofilm reactor to create a stable oral biofilm community that closely simulates the in vivo environment. While the biofilms grown in the CDC reactors underwent significant changes in their microbiological composition, around 60 % of the species were preserved [15]. Specimens placed in the reactor can be removed at predetermined time points for assessment of biofilm characteristics, demineralization profiles of dental tissues and degradation of dental materials. Our CDC reactor model also allows for real-time measurement of pH response curves when the reactor is pulsed with sucrose, to simulate acidogenic meals and snacks.

As mentioned above, we are interested in knowing whether oral biofilms can actively reduce the bond strength of the underlying interfaces of a composite restoration. Many mechanical test methods have been used to measure the bond strength between filling materials and tooth tissues, such as the microtensile test, shear test and push-out test [16]. In parallel with our development of the CDC reactor model, we also optimized a system for evaluating failure at the dentin - adhesive - composite interface [17], a major component in a composite restoration. In that system, dentin disks are made from bovine incisor roots, and the canal is enlarged and filled with composite (Fig. 1). The disk is then subjected to diametral compression, with acoustic emission (AE) and digital image correlation (DIC) being used to determine the time and location at which failure occurs. The disks consistently fail by first debonding at the dentin-composite interface. It is therefore a valid bond test and results have shown that it provides more precise bond strength measurements.

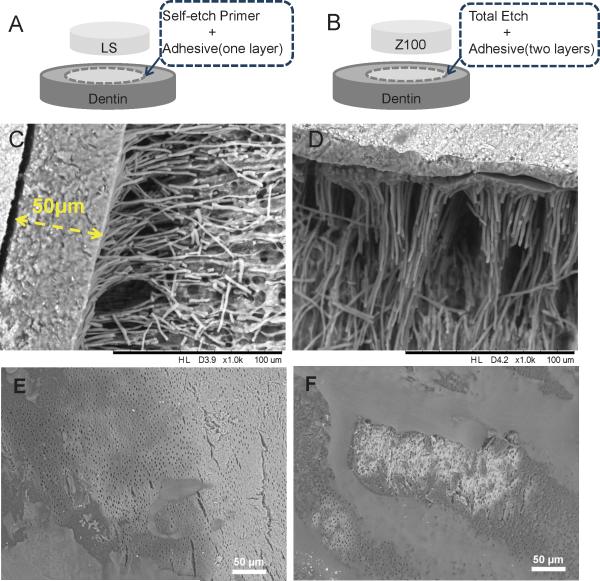

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrations of dentin-composite disks of LS (A) and Z100 (B). SEM images of LS (C) and Z100 (D) dentin-composite disks after demineralization and deproteinization, showing the adhesive layers and resin tags. SEM images of one layer (E) and two layers (F) of Z100 adhesive applied on etched dentin surfaces showing incomplete coverage.

In this study, we combined our previously validated CDC reactor model and dentin-composite disk interfacial failure model to address the following questions: 1.) Does the presence of a multi-species biofilm lead to degradation of the dentin-composite interface? 2.) Does sucrose-pulsing enhance the effects of biofilm at the interface? 3.) Do biofilm effects at the interface differ between composite-adhesive systems with different chemistries?

Materials and Methods

2.1 Dentin-composite disks

The dentin-composite disks used in this study are illustrated in Fig. 1A and B. Bovine incisors were used to prepare the disk specimens. The crowns were cut off at the cemento-enamel junction with a rotary diamond saw (Buehler, USA) under cooling water to provide the portion of root dentin from the incisors. These were then trimmed down into dentin cylinders of 5 mm in diameter using a lathe, and the root canals were enlarged to 2 mm in diameter using Gates-Glidden drills. After that, the dentin cylinders were rinsed with deionized water to remove any remnants. They were then randomly divided into two groups, and filled with one of two composites (Z100™ and Filtek ™ LS, both 3M ESPE) using the corresponding adhesives as per the manufacturer's instructions. Z100 and LS were chosen as they represented composites with very different chemistries, bonding systems and shrinkage behaviors. For specimens filled with Z100, the inner dentin surface was etched with 35% phosphoric acid for 20s before rinsing with deionized water. Two consecutive layers of adhesive (Adper™ Single Bond Plus, 3M ESPE) were applied to the etched surface, with each layer being cured for 20s. Z100, a methacrylate-based resin restorative composite, was then applied incrementally to fill the cylinders. Each increment was cured for 40s to ensure adequate curing of the material. For specimens filled with LS, a layer of Self-Etch Primer (LS System Adhesive, 3M ESPE) was first applied and cured for 10s. This was followed by the application of a layer of Self-Etch Bond (LS System Adhesive, 3M ESPE) with 20s of curing. LS, a low-shrinkage silorane-based restorative composite, was then applied incrementally and cured in the same way as Z100. Finally, the filled cylinders were transversely cut to produce 2-mm thick round disks.

2.2 Human subjects and biofilm stocks

Primary teeth have a higher reported risk of secondary caries with resin-based restorations than permanent dentition since some pediatric dental patients may provide a more challenging oral environment due to their dietary habits [3, 18]. Twelve pediatric dental patients with histories of early childhood caries and a median age of 9 years were recruited as plaque and saliva donors. After explaining the risks and benefits of the study, written consent was obtained from the children's legal guardians for all children enrolled in the study. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. A detailed description of the procedures used for sample collection is provided in our previous paper on the CDC reactor model [15]. Briefly, subjects were asked to refrain from oral hygiene at bedtime and in the morning before sample collection. A sample of resting whole saliva was collected, centrifuged, filter-sterilized, and stored in aliquots at – 80 ° C. After saliva collection, a sample of dental plaque from either the occlusal or buccal margin of an existing restoration was collected into a vial containing 1 ml pre-reduced anaerobic transfer medium (Anaerobe Systems, Morgan Hill, CA, USA) to help preserve the anaerobes also present in supragingival plaque. Biofilm stocks were made by growing microcosms from the plaque of individual subjects, onto hydroxyapatite disks (HA, Clarkson Chromatography, South Williamsport, PA, USA) in the CDC reactor [15]. The saliva sample was clarified by centrifugation, diluted twofold in a buffer that simulates the ionic composition of saliva and then sterilized with a 0.2-μm filter. HA discs were precoated with sterilized saliva to form a pellicle. The matching plaque suspension was dispersed by sonification and 30 μl of it was applied onto each disc. The disks were then placed immediately into the reactor. After 72 hr of incubation, the biofilms were then removed and pooled, re-suspended in BMM with 20% glycerol, and stored at −80 °C. Stocks were used to provide the inoculum for biofilm challenge in most cases. Fresh plaque was available for a few subjects. In those cases, biofilm challenges were run at the same time that stocks were prepared.

2.3 In vitro biofilm challenges

A full description of our CDC Biofilm Reactor based oral microcosm model [19] has been published previously [15]. Briefly, it incorporates a lidded vessel through which growth media can be flowed at a defined rate, and a baffled stir bar to generate shear. Rods inserted through the lid are used to mount samples. Basal Mucin Medium (BMM) containing hog gastric mucin as the primary source of carbohydrate was used as the growth medium [20]. Microcosms were incubated aerobically, to better replicate conditions existing in supragingival plaque.

One biofilm challenge was run for every subject. For each challenge, fourteen Z100 and fourteen LS composite-dentin disks were prepared, and stored in 1% (v/v) thymol at room temperature until needed. The disks were coated with acid-resistant nail varnish except one side of the composite filling and a 1 mm perimeter around it, so that the associated interface was exposed. The disks were disinfected with 70% ethanol before mounting and inserting into the reactor. Each exposed surface was coated with 30 μl of sterilized human saliva, and then treated with 30 μl plaque/stock from the same donor. Seven disks of each material then were placed into two pre-autoclaved CDC reactors, each containing 350 ml Basal Mucin Medium (BMM), and incubated at 37° C under constant shear (125 rpm) for 24 hr. BMM was then flowed through one reactor at 17 ml/min (125 rpm; 37° C) for another 48 hr. The second reactor was pulsed five times per day (20 v/v%, 43 ml each time) analogous to three meals and two snacks for the 2nd and 3rd days (the flow rate for the second reactor was set at 20 ml min−1, to reduce fouling). Sucrose pulsing was discontinued during the nights. To determine real-time pH, a fitting was machined so that an autoclavable pH electrode could be placed in each reactor. The pH was recorded every 15 min throughout the 72-hr incubation.

Three control experiments were conducted in which disks were coated only with sterilized human saliva and incubated in the CDC bioreactor using the sucrose pulsing protocol described above.

2.4 Mechanical tests

After the biofilm challenge, the disks were rinsed with distilled water and the nail varnish removed with a stainless steel spatula. The bond strengths of the disks were determined by the diametral compression test (Brazilian disk test) using a universal test machine (858 Mini Bionix II, MTS, MN, USA) with two parallel horizontal plates [17]. The load was applied in a stroke-control mode at a loading speed of 0.5 mm min−1. Acoustic Emission (AE) and Digital Image Correlation (DIC) were used during the compression tests to monitor the debonding process. Using an AE system (Physical Acoustics Corporation, NJ, USA), acoustic signals produced from microcracking during loading were detected by an AE sensor attached to the lower stationary plate on which the specimens were placed. Data obtained from the AE events were used in combination with the load-displacement histories from the universal test machine to determine when debonding at the tooth-restoration interface occurred. The DIC technique was used to track the change in surface strains on the disks during loading. This was to ensure that interfacial debonding, manifested as high strain concentrations at the dentin-composite interface, occurred before whole disk fracture. A thin layer of white, and then black, paint was sprayed on the surface of the disks facing the CCD camera of the DIC system to facilitate displacement tracking and processing. Photographs were taken continuously at a rate of 30 fps during the compression test and then analyzed by the DIC software (DaVis 7.0, Lavision, Germany) to produce the strain maps.

2.5 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM was used to examine the morphology of the resin tags, decalcification and fracture modes of the disks. In order to expose the resin tags, a 37% H3PO4 gel was applied to freshly prepared dentin-composite disks (Z100 and LS) for 30 minutes, followed by an air-water spray rinse for 15 s. Subsequently, the specimens were immersed in NaOCl (7 ± 2%) for 30 min, followed by rinsing with distilled water for three times. All etched specimens and fractured disks were mounted on aluminum stubs with carbon tape and examined by a tabletop SEM (TM-3000, Hitachi, Japan) operated at a 15-kV accelerating voltage in combo mode, i.e., surface morphology was shown in stereoscopic detail with images in contrast due to different average atomic number compositions within the sample. Demineralization of the exposed dentin was assessed by an Energy-dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) unit (Quantax 70, Bruker, Germany) attached to the SEM.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The bond strengths for the 7 dentin-composite replicate disks for each of the four conditions within the biofilm trials for each of the 12 subjects were averaged to create within-subjects means for the following groups: Z100 Biofilm No Sucrose (Z100_BNS), Z100 Biofilm With Sucrose (Z100_BWS), LS Biofilm No Sucrose (LS_BNS), and LS Biofilm With Sucrose (LS_BWS). The within-subject means then were analyzed using a two-way repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), with Material and Sucrose as the within-subject factors. Within-run means likewise were generated for each of the three sterile media control runs with sucrose pulsing. The controls were compared to the Z100_BWS and LS_BWS groups using a two–way mixed model ANOVA with Biofilm as the between-group factor and Material as the within-subject factor. Although we did not run controls without sucrose, the same design was used to compare the sucrose controls to the Z100_BNS and LS_BNS groups.

Results

3.1 Composite-dentin interface and resin tag assessment

The adhesive systems for both LS and Z100 produced resin tags of a similar thickness (Fig. 1C and D). The self-etching system used in LS yielded an adhesive layer of ~ 50 μm thick without any observable gaps or voids within the layer (Fig. 1C). The three-step ‘etch and rinse’ adhesive system used in Z100 yielded a thinner adhesive layer of 10 to 20 μm, despite the two applications. Delamination between the two sub-layers after demineralization and deproteinization of the dentin could be seen in some locations (Fig. 1D). Further examination using SEM of the adhesive layers, without the application of composites, showed that the Z100 adhesive did not fully cover the dentin surface (Fig. 1E). Likewise, the second sub-layer did not fully cover the first (Fig. 1F).

3.2 Effect of sucrose pulsing on the pH of biofilms

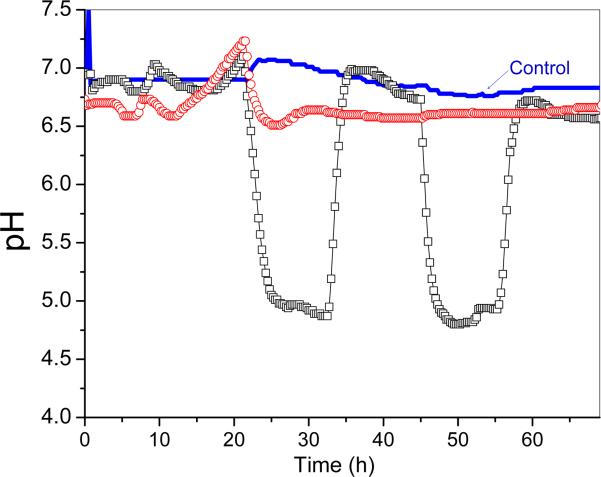

The real-time pH recordings for the biofilms with (WS) and without (NS) sucrose pulsing for each subject are presented in Fig. 2. The overall patterns were similar across subjects except during the first day of bacterial inoculation (Fig. S1). The pH of both the NS and WS biofilms remained relatively high during this period, with a generally small reduction from neutral to around 5.5 - 6.5, depending on the subject. On the second and third day, the pH of the biofilms with sucrose pulsing fell rapidly during the first two pulses, and dropped below 5.5. The pH remained below that threshold for several hours after the final pulse of each day. It then rose rapidly back above 6.0. In the corresponding reactor where sucrose was not added, the pH of the biofilms remained above 6.0 at all times. The pH from the control runs without biofilms remained at ~7 throughout the 72-hr incubation, even though sucrose was pulsed on day 2 and day 3.

Figure 2.

Real-time pH recordings from the bioreactors during the 72-hr biofilm challenge (subject #778). (-○-) Biofilm challenge without sucrose pulsing, (-□-) Biofilm challenge with sucrose pulsing, (---) Control with sucrose pulsing but no biofilms.

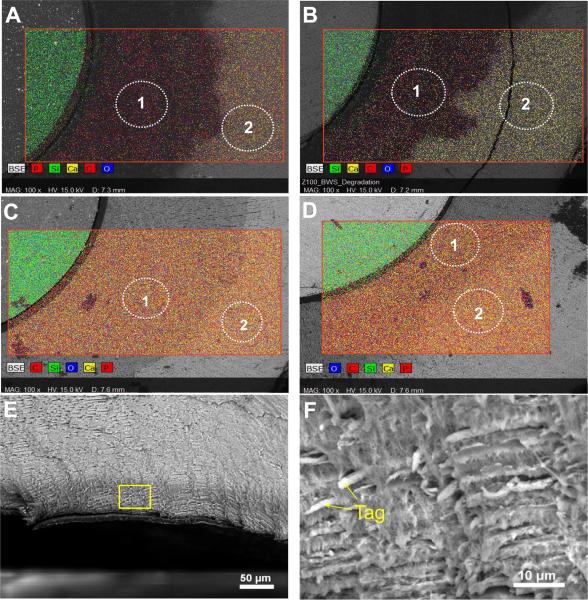

3.3 Biofilm effects on morphology of exposed dentin

Extensive decalcification occurred in the exposed dentin challenged by biofilms with sucrose pulsing (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The region of exposed dentin looked darker in the SEM images and had less than 2% of Ca and P in both the LS and Z100 disks, whereas the outer region of dentin protected by the nail varnish showed ~14% of Ca and ~8% of P. On the fractured surfaces, a decalcification depth of ~ 50 μm could be seen as a darker band at the dentin, because of the low mineral content. Closer examination of this region revealed a network of exposed collagen fibrils (Fig. 3E and F). Without sucrose pulsing, only a small reduction in Ca and P contents was found in the exposed dentin, even in the presence of biofilms (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

SEM, EDS mapping and elemental analysis of dentin-composite disks exposed to biofilm challenges. (A) LS after biofilm challenge with sucrose pulsing. (B) Z100 after biofilm challenge with sucrose pulsing. (C) LS after biofilm challenge without sucrose pulsing. (D) Z100 after biofilm challenge without sucrose pulsing. Regions marked as 1 are exposed dentin and 2 are dentin covered with nail varnish during the biofilm challenge. (E) SEM image of fractured surface of an LS disk specimen after biofilm challenge with sucrose pulsing, showing a dark band of decalcified dentin at the surface. (F) Higher-magnification SEM image of the demineralized dentin showing exposed collagen fibril networks and resin tags.

Tabel 1.

Elements distribution of exposed restorations in atomic percentage

| Specimen | Region[a] | O | C | Ca | P | Si |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS_BWS | 1 | 34.7 | 62.1 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 51.5 | 26.3 | 14.3 | 7.7 | 0.1 | |

| LS_BNS | 1 | 46.2 | 35.6 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 52.1 | 24.6 | 15.3 | 7.8 | 0.1 | |

| Z100_BWS | 1 | 31.6 | 63.7 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 51.7 | 25.8 | 14.4 | 7.9 | 0.1 | |

| Z100_BNS | 1 | 46.5 | 35.8 | 10.9 | 5.6 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 51.4 | 25.5 | 14.5 | 8.0 | 0.1 |

regions 1 and 2 were labeled in Fig. 3 showing the location where EDS was taken from.

3.4 Bond strength of dentin-composite disks

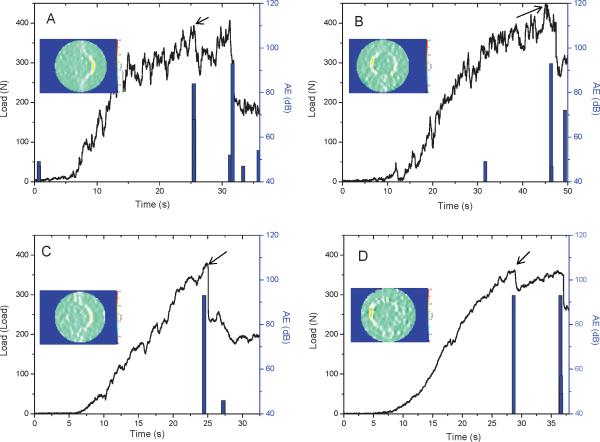

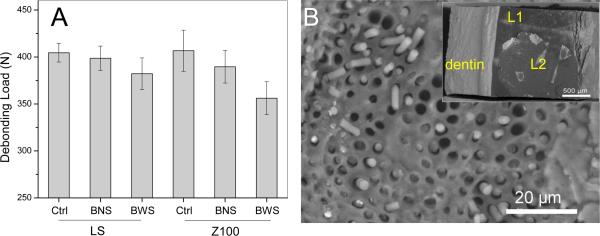

Representative load-displacement curves from the diametral compression tests of the four groups of dentin-composite disks after biofilm challenge are shown in Fig. 4. Most of the disks deformed rather linearly with increasing load until debonding took place, at which point both a drop in load, as indicated by the arrows, and a significant AE event could be detected. DIC analysis confirmed that debonding occurred at the dentin-composite interface prior to whole-disk fracture, as shown by the high strain concentration (orange color) at the interface where the tensile stress was maximum (inserts in Fig. 4, and video). The fracture loads of all the disks after biofilm challenge with the 12 different subjects are shown in Fig. S2. The averaged debonding loads for the four groups (LS_BNS, LS_BWS, Z100_BNS and Z100_BWS) are shown in Fig. 5A. The two-way repeat measures ANOVA indicated that the bond strengths for LS were significantly higher than for Z100, when averaged over both the NS and WS conditions (p = 0.003). Bond strengths were significantly reduced by biofilm with sucrose pulsing, when averaged over both materials (p < 0.001). The interaction between Materials and Sucrose was not statistically significant. However, the magnitude of the difference between Z100 and LS means was approximately two-fold greater under BWS conditions (24.8 N) relative to BNS conditions (10.2 N). The mixed-model ANOVA comparing controls to sucrose-pulsed biofilms indicated that bond strengths were significantly lower after exposure to sucrose-pulsed biofilms, when averaged over both materials (p = 0.002). The difference between bond strengths for LS and Z100 averaged over both the sucrose-pulsed biofilm and control groups verged on significance (p = 0.055). The interaction term was not significant, but the magnitude of the mean difference between sucrose-pulsed biofilm and controls was two-fold greater for Z100 (41.1 N) than for LS (21.3 N). When the same model was used to compare the sucrose pulsed controls to biofilms without sucrose, there were no significant differences between biofilms and controls, or Z100 and LS. Collectively, these results suggested that bond strengths for Z100 and LS were essentially similar in the absence of biofilm. In the absence of sucrose pulsing, biofilm appeared to induce a modest reduction in the bond strength of Z100 relative to LS. Sucrose-pulsed biofilms induced reductions in bond strength for both materials, but the magnitude of the change was considerably greater for Z100 than for LS.

Figure 4.

Typical load-displacement curves and acoustic emission (AE) signals (bars) from the diametral compression tests of LS and Z100 disks after being subjected to biofilm challenges with or without sucrose pulsing. (A) LS after biofilm challenge without sucrose pulsing. (B) Z100 after biofilm challenge without sucrose pulsing. (C) LS after biofilm challenge with sucrose pulsing. (D) Z100 after biofilm challenge with sucrose pulsing. Inserts are images from digital image correlation showing surface strains on the disks during loading. The arrows indicate load drops due to debonding.

Figure 5.

(A) Debonding loads averaged over the 12 subjects of dentin-composite disks with different bioreactor conditions. Ctrl: Control with no biofilms; BNS: biofilm without sucrose pulsing; BWS: biofilm with sucrose pulsing. The top of each bar indicates the mean of the values for all 12 subjects, and the error bars are standard deviations. (B) SEM image of the fracture surface of a Z100 disk specimen showing broken resin tags and adhesive. Insert is a lower-magnification SEM image of the same fracture surface: the top layer is the second adhesive layer (L2) debonded from the composite, while another thin layer of adhesive (L1) on dentin can be found below L2. The steps between the two layers indicate that part of the top layer was delaminated from the bottom layer.

3.5 Failure analysis

Table 2 shows the number and percentage for each of the interfacial failure modes observed in the diametral compression tests of the dentin-composite disks. The LS group exhibited three interfacial failure modes: (1) mixed failure mode including cohesive failure in the resin composite and partial adhesive-composite interfacial failure (C + AC); (2) interfacial failure between the adhesive and composite (AC); and (3) interfacial failure between the adhesive and dentin (AD). The most frequent failure mode for LS was adhesive-composite interfacial failure (50%), followed by mixed failure (30%) and then adhesive-dentin interfacial failure (20%), regardless of the type of biological challenge. In contrast, the failure modes of Z100 at the dentin-composite interface were predominantly cohesive failure in the adhesive (>80%), again regardless of the type of biological challenge. A small number of interfacial failures between either the adhesive and composite or the adhesive and dentin were observed. Broken resin tags on the dentin side of the fracture surfaces and delamination between the two adhesive layers could also be seen in the Z100 samples (Fig. 5B).

Table 2.

Number (percentage) of specimens failed with a particular fracture mode for LS and Z100 samples under the different experimental conditions

| LS | Control | BNS | BWS | Z100 | Control | BNS | BWS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC+C | 5(29.4) | 22(30.6) | 26(35.1) | A | 13(81.3) | 73(96.1) | 66(94.3) |

| AC | 8(47.1) | 39(54.2) | 34(45.9) | AC | 1(6.3) | 1(1.3) | 2(2.9) |

| AD | 4(23.6) | 11(15.3) | 14(18.9) | AD | 2(12.6) | 2(2.6) | 2(5.8) |

Control: specimens coated with saliva only and subjected to sucrose pulsing; BNS: biofilm challenge without sucrose pulsing; BWS: biofilm challenge with sucrose pulsing.

AC+C: mixed failure mode includes cohesive failure in resin composite and partial adhesive-composite interfacial failure. AC: adhesive-composite interfacial failure. AD: adhesive-dentin interfacial failure. A: cohesive failure in adhesive layer.

Discussion

Dental composite restorations reportedly have a shorter lifespan and higher rate of replacement than amalgam restorations due, primarily, to the development of microleakage around the margin of the restorations and subsequent secondary caries in the surrounding tooth tissues [21, 22]. Further, 80% to 90% of secondary caries was located at the gingival margins of Class II through V restorations [6, 7]. The initiation of marginal failure has been attributed to shrinkage stress caused by the polymerization of the composite resin and cyclic fatigue through mastication. The lifetime of a composite restoration therefore depends strongly on the strength of the restorative and adhesive materials as well as the quality of the integration of the interfacing materials and tissues. Degradation of the tooth-restoration interface can also be caused by the chemical and biological agents that exist in the oral cavity, in particular the cariogenic bacteria that form plaque on the surfaces of teeth and restorations. By using an oral microcosm model together with sucrose pulsing to simulate the conditions present in the mouth, and the modified diametral compression test for bond strength measurement, we investigated the effect of biofilm on the degradation of the dentin-composite interface. It should be emphasized that the disk specimen proposed here is not meant to represent the entire restoration, but only one of its major components; i.e., the dentin-composite interface.

Many mechanical test methods have been used to evaluate the bond strength between filling materials and dentin, e.g. the micro-tensile test and the shear test [16, 23]. Because the specimens are small in the micro-tensile test, extensive machining is required which can lead to large amount of premature failure and significant variation in bond strength measurement. It also requires much effort to secure the specimens onto the loading jigs. In contrast, our modified diametral compression discs proposed here require simpler specimen preparation and loading. In the shear test, the interfacial stress distribution is highly non-uniform and in the push-out version the final failure load is affected by the significant friction between the restoration and dentin [24]. More importantly, interfacial failure in composite-restored teeth usually happens in an opening (tensile) mode under the occlusal forces or shrinkage stress [25-27]. Similar to the widely used, uniaxial tensile test using bar specimens, the disc in diametral compression is a simple way to induce such type of failure at the interface. Besides, they could be easily fitted into the rods within the CDC biofilm reactor to study both the bond strength reduction and demineralization.

Sucrose is considered the most cariogenic dietary carbohydrate as it leads to the production of organic acids by bacterial fermentation (e.g., lactic, acetic, propionic, succinic or formic), and it is also metabolized to form intracellular and extracellular polysaccharides by microorganisms from the dental plaque. The relationship between sucrose intake and caries development has been demonstrated in several studies [28, 29]. The metabolism of sucrose causes a fall in the pH level in the plaque, and dental caries is the direct consequence of the resulting dissolution of mineral. Our biofilm model with sucrose pulsing produced pH - time curves (Fig. 2) that were similar to those observed in intraoral studies of plaque pH after sucrose rinsing [30, 31]. The pH dropped to a value below 5, and it remained at that level for up to 8 hrs during which sucrose was pulsed 5 times to simulate food intake. Once sucrose pulsing was discontinued and most of the sucrose was consumed, the pH value returned rapidly to the more neutral level of 6 – 7, due to the constant flow of growth medium throughout the night. A slight reduction of the pH to around 5.5 – 6.5 occurred on the first day of bacterial inoculation, which was possibly related to acid production by the bacteria from metabolism of mucin polysaccharides. The same drop in pH on the first day could also be seen in the biofilm without sucrose pulsing.

The CDC biofilm reactor model used in this study has been shown to be able to produce reproducible microcosm biofilms that were representative of the oral microbiota [15]. It provides an aerobic environment similar to the human mouth for the growth of oral biofilm. There are over 500 bacterial species identified so far in the dental plaque [32]. The Human Oral Microbial Identification Microarray (HOMIM) system detected and evaluated the relative abundance of 272 species and about 60% of species from the original inoculum was detected from microcosms [15]. Even though plaques from 12 different subjects were used for this study, the pH-time pattern and bond strength change for each subject were similar.

Enamel demineralization usually occurs when the pH is lower than 5.5 [33] and dentin demineralization can begin at pH 6.7 [34]. It therefore was not surprising to see demineralization in the dentin-composite disks where dentin was exposed. The demineralized dentin reached a maximum depth of around 50 μm for both material groups. Assuming the debonding load to be proportional to the thickness of the disk, which was 4 mm originally, a reduction of 50 μm should produce a 2.5% drop in the debonding load. Contrary to expectation, more significant reductions in the debonding load were found for our specimens, especially those prepared with Z100 and subjected to biofilm challenge with sucrose pulsing. This, together with the fact that the two material groups demonstrated different reductions in debonding load despite their similar levels of dentin demineralization, suggested that factors other than surface demineralization were also responsible for the reduction in debonding load.

The adhesive-dentin interface has been shown to be a weak link in the composite restoration [35]. It is generally accepted that resin-dentin bonds obtained with contemporary hydrophilic mathacrylate-based adhesives will deteriorate over time even in the absence of mechanical loading [36]. In the oral environment, water can enter into the polymer matrix by diffusion, causing a reduction of glass-transition temperature, polymer plasticization and a decrease in thermal stability [37]. As a result, this can lead to hygrothermal degradation, hydrolysis and resin leaching [38]. Hydrolysis is a chemical process that breaks the covalent bonds within the polymer by addition of water to the ester bonds. It is considered one of the main reasons for resin degradation within the hybrid layer [39, 40]. In oral fluids, the ester bonds within the methacrylate polymer matrix are vulnerable to two forms of hydrolytic attack: chemical hydrolysis and enzymatic hydrolysis. Since the bond strength was not significantly affected in the absence of biofilm, or in the presence of biofilm without sucrose, water sorption within polymer by itself is not sufficient to explain the reduction in bond strength caused by sucrose pulsed biofilm. Acids or bases can catalyze the chemical hydrolysis and make the polymer matrix more hydrophilic [35]. This may explain the lower bond strength with sucrose pulsed biofilm. Saliva and biofilm contains a variety of enzymes which may participate in the degradation of the resin. The esterase-catalyzed degradation of methacrylate esters and commercial dental resins has been documented [41, 42]. It is possible that extracellular enzymes released only when sucrose is available might contribute to the degradation of the interface. Such effects might be direct or indirect, since the formation of insoluble glucans by Streptococcus mutans has been shown to create zones of intense acidification associated with microcolonies in contact with the HA surface [43]. Thus, pH under sucrose-pulsed biofilms might be even lower than the pH in the reactor overall. Furthermore, water sorption can be enhanced by the presence of hydrophilic domains and resin monomers with ionic functional groups [44, 45], which in turn, facilitate ion movement within a polymerized matrix. Water movement promotes hydrolytic degradation and release of the hydrolyzed components of the adhesive layer. This, associated with an increase in permeability of the adhesive layer, creates a vicious cycle that accelerates the deterioration of the mechanical properties of the adhesive layer [46].

The bonding between composite and dentin is of a micromechanical nature, through formation of the resin tags, hybrid layer and adhesive layer, as a result of the acid etching and resin infiltration into the dentinal tubules [47]. The adhesive systems for both LS and Z100 were able to infiltrate the etched dentin, forming funnel-shaped resin tags along the entire root canal (Fig. 1C and D). Z100 requires a full process of etching and rinsing, and two consecutive coatings of an adhesive that required curing, while LS is intended for use with a self-etching primer and a single coat of adhesive more viscous than that used with Z100. As a result, the LS specimens had a thicker layer of adhesive (Fig. 1C). Despite its better handling characteristics, inadequate coverage of the dentin surface by the adhesive was found in the Z100 specimens, and steps could be seen between the two layers of adhesive. These defects in the adhesive layers could have provided channels for water infiltration from the dentin underneath or exposed interface, leading to faster hydrolytic degradation of the adhesive. Similarly, the high shrinkage stress of Z100 could have created partial debonding at the dentin-composite interface to provide more channels for water and acid infiltration. In contrast, dentin in the LS samples was well covered by the thick layer of adhesive, and LS has a very low shrinkage stress. Degradation of the dentin-composite interface in the LS samples was therefore expected to take place at a slower rate. This may explain why the Z100 samples had a greater reduction in their bond strength after the biofilm challenge and a higher proportion of cohesive failure in the adhesive. In contrast, the LS samples had a more even distribution amongst the different interfacial fracture modes and a lower reduction in the bond strength after biofilm challenge. Incidentally, the reduction in failure load appeared to be uniform across all the fracture modes, i.e. no particular fracture mode had a higher reduction in the failure load than others.

Bovine teeth, instead of human teeth, were used in this study. The use of bovine teeth in dental studies has dramatically increased in the last 30 years since they are easy to obtain in large quantities and good condition. There appear to be small differences in morphology, chemical composition and physical properties between bovine and human teeth. In some bond strength studies, human tissues show higher bond strength than bovine tissues while others show no significant difference between them [48]. Another study found no significant difference between human root and bovine root dentin in caries progression, inhibition and composition of biofilm formed [49]. On balance, therefore, bovine dentin can be considered a suitable model for human dentin for bond strength and demineralization studies.

In real restored teeth, secondary caries can also occur on occlusal and proximal surfaces that involve enamel and crown dentin. These are different from root dentin in terms of morphology, chemical composition and physical properties. Also, in our disk specimens made with bovine incisor roots, the dentinal tubules were always perpendicular to the dentin-composite interface (Fig. 1C and D). The orientations of the dentinal tubules in real life cavities are more varied, especially at the cavity walls. The integrity of the dentin-composite interface here might be more vulnerable to biofilm challenge since resin tags are not fully formed. This, together with the possibility that human dentin may behave differently from bovine dentin, means that caution must be exercised when trying to extend the current results to real life composite restorations in general.

Notwithstanding the limitations mentioned above, our current study demonstrated clearly the effect of microcosm biofilms in degrading dentin-composite interfacial bond. Future studies will focus on the combined effects of biofilms and cyclic loading on the degradation of dentin-composite interfaces, and will make use of specimens that also include enamel.

Conclusion

Our in vitro investigation has provided the following answers to the questions we posed at the beginning of this paper. 1) The presence of a multi-species biofilm led to degradation of the dentin-composite interface. 2) For the duration of biofilm challenge considered in this study, sucrose pulsing was essential to ensure that the degradation effects were significant. 3) The biofilm effects differed between the restorative systems, with samples prepared with Z100 suffering more degradation. In addition, the results suggested that factors other than dentin demineralization were also responsible for the bond strength reduction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grant 1 R01 DE021366 from the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Beazoglou T, Eklund S, Heffley D, Meiers J, Brown LJ, Bailit H. Economic impact of regulating the use of amalgam restorations. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:657–663. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowen RL, Marjenhoff WA. Dental composites/glass ionomers: the materials. Adv Dent Res. 1992;6:44–49. doi: 10.1177/08959374920060011601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernardo M, Luis H, Martin MD, Leroux BG, Rue T, Leitao J, et al. Survival and reasons for failure of amalgam versus composite posterior restorations placed in a randomized clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:775–783. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickel R, Manhart J, Garcia-Godoy F. Clinical results and new developments of direct posterior restorations. Am J Dent. 2000;13:41D–54D. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manhart J, Neuerer P, Scheibenbogen-Fuchsbrunner A, Hickel R. Three-year clinical evaluation of direct and indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;84:289–296. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2000.108774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mjor IA. Clinical diagnosis of recurrent caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1426–1433. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mjor IA. The location of clinically diagnosed secondary caries. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sbordone L, Bortolaia C. Oral microbial biofilms and plaque-related diseases: microbial communities and their role in the shift from oral health to disease. Clin Oral Invest. 2003;7:181–188. doi: 10.1007/s00784-003-0236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreth J, Zhang Y, Herzberg MC. Streptococcal antagonism in oral biofilms: Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii interference with Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4632–4640. doi: 10.1128/JB.00276-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sansone C, Vanhoute J, Joshipura K, Kent R, Margolis HC. The Association of Mutans Streptococci and Non-Mutans Streptococci Capable of Acidogenesis at a Low Ph with Dental-Caries on Enamel and Root Surfaces. J Dent Res. 1993;72:508–516. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720020701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ono M, Nikaido T, Ikeda M, Imai S, Hanada N, Tagami J, et al. Surface properties of resin composite materials relative to biofilm formation. Dent Mater J. 2007;26:613–622. doi: 10.4012/dmj.26.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gyo M, Nikaido T, Okada K, Yamauchi J, Tagami J, Matin K. Surface response of fluorine polymer-incorporated resin composites to cariogenic biofilm adherence. Appl Environ Microb. 2008;74:1428–1435. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02039-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayati F, Okada A, Kitasako Y, Tagami J, Matin K. An artificial biofilm induced secondary caries model for in vitro studies. Aust Dent J. 2011;56:40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cenci MS, Pereira-Cenci T, Cury JA, Ten Cate JM. Relationship between gap size and dentine secondary caries formation assessed in a microcosm biofilm model. Caries Res. 2009;43:97–102. doi: 10.1159/000209341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudney JD, Chen R, Lenton P, Li J, Li Y, Jones RS, et al. A reproducible oral microcosm biofilm model for testing dental materials. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113:1540–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goracci C, Grandini S, Bossu M, Bertelli E, Ferrari M. Laboratory assessment of the retentive potential of adhesive posts: A review. J Dent. 2007;35:827–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang SH, Lin LS, Rudney J, Jones R, Aparicio C, Lin CP, et al. A novel dentin bond strength measurement technique using a composite disk in diametral compression. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:1597–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pascon FM, Kantovitz KR, Caldo-Teixeira AS, Borges AF, Silva TN, Puppin-Rontani RM, et al. Clinical evaluation of composite and compomer restorations in primary teeth: 24-month results. J Dent. 2006;34:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goeres DM, Loetterle LR, Hamilton MA, Murga R, Kirby DW, Donlan RM. Statistical assessment of a laboratory method for growing biofilms. Microbiology. 2005;151:757–762. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sissons CH, Anderson SA, Wong L, Coleman MJ, White DC. Microbiota of plaque microcosm biofilms: effect of three times daily sucrose pulses in different simulated oral environments. Caries Res. 2007;41:413–422. doi: 10.1159/000104801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mjor IA, Dahl JE, Moorhead JE. Age of restorations at replacement in permanent teeth in general dental practice. Acta Odontol Scand. 2000;58:97–101. doi: 10.1080/000163500429208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke FJT, Wilson NHF, Cheung SW, Mjor IA. Influence of patient factors on age of restorations at failure and reasons for their placement and replacement. J Dent. 2001;29:317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(01)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reinke SMG, Lawder JAD, Divardin S, Raggio D, Reis A, Loguercio AD. Degradation of the resin-dentin bonds after simulated and inhibited cariogenic challenge in an in situ model. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2012;100B:1466–1471. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goracci C, Fabianelli A, Sadek FT, Papacchini F, Tay FR, Ferrari M. The contribution of friction to the dislocation resistance of bonded fiber posts. J Endodont. 2005;31:608–612. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000153841.23594.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hood JA. Experimental studies on tooth deformation: stress distribution in class V restorations. The New Zealand dental journal. 1972;68:116–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rees JS, Jacobsen PH. The effect of interfacial failure around a class V composite restoration analysed by the finite element method. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2000;27:111–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2000.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heymann HO, Sturdevant JR, Bayne S, Wilder AD, Sluder TB, Brunson WD. Examining tooth flexure effects on cervical restorations: a two-year clinical study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(91)25015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cury JA, Rebelo MAB, Cury AAD. Derbyshire MTVC, Tabchoury CPM. Biochemical composition and cariogenicity of dental plaque formed in the presence of sucrose or glucose and fructose. Caries Res. 2000;34:491–497. doi: 10.1159/000016629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tenuta LMA, Ricomini AP, Cury AAD, Cury JA. Effect of sucrose on the selection of mutans streptococci and lactobacilli in dental biofilm formed in situ. Caries Res. 2006;40:546–549. doi: 10.1159/000095656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.AamdalScheie A, Luan WM, Dahlen G, Fejerskov O. Plaque pH and microflora of dental plaque on sound and carious root surfaces. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1901–1908. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750111301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng DM, ten Cate JM. Demineralization of dentin by Streptococcus mutans biofilms grown in the constant depth film fermentor. Caries Res. 2004;38:54–61. doi: 10.1159/000073921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosan B, Lamont RJ. Dental plaque formation. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1599–1607. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ilie O, van Loosdrecht MCM, Picioreanu C. Mathematical modelling of tooth demineralisation and pH profiles in dental plaque. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2012;309:159–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banting DW. The diagnosis of root caries. Journal of dental education. 2001;65:991–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spencer P, Ye Q, Park J, Topp EM, Misra A, Marangos O, et al. Adhesive/Dentin Interface: The Weak Link in the Composite Restoration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:1989–2003. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koshiro K, Inoue S, Sano H, De Munck J, Van Meerbeek B. In vivo degradation of resin-dentin bonds produced by a self-etch and an etch-and-rinse adhesive. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113:341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferracane JL. Hygroscopic and hydrolytic effects in dental polymer networks. Dent Mater. 2006;22:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reis A, Ferreira SQ, Costa TRF, Klein-Junior CA, Meier MM, Loguercio AD. Effects of increased exposure times of simplified etch-and-rinse adhesives on the degradation of resin-dentin bonds and quality of the polymer network. Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118:502–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Have dentin adhesives become too hydrophilic? J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:726–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Water treeing--a potential mechanism for degradation of dentin adhesives. Am J Dent. 2003;16:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finer Y, Santerre JP. The influence of resin chemistry on a dental composite's biodegradation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;69:233–246. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donmez N, Belli S, Pashley DH, Tay FR. Ultrastructural correlates of in vivo/in vitro bond degradation in self-etch adhesives. J Dent Res. 2005;84:355–359. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao DW, Huang XC, Zheng YJ, Huang JX, Li KKH, Fok TF, et al. Circulating megakaryocytes during cardiopulmonary bypass and influence on neurological complications post-operation. Blood. 2003;102:79b–79b. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ito S, Hashimoto M, Wadgaonkar B, Svizero N, Carvalho RM, Yiu C, et al. Effects of resin hydrophilicity on water sorption and changes in modulus of elasticity. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6449–6459. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wadgaonkar B, Ito S, Svizero N, Elrod D, Foulger S, Rodgers R, et al. Evaluation of the effect of water-uptake on the impedance of dental resins. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3287–3294. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tay FR, Pashley DH, Suh BI, Hiraishi N, Yiu CKY. Water treeing in simplified dentin adhesives - Deja Vu? Oper Dent. 2005;30:561–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferrari M, Vichi A, Grandini S. Efficacy of different adhesive techniques on bonding to root canal walls: an SEM investigation. Dent Mater. 2001;17:422–429. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(00)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yassen GH, Platt JA, Hara AT. Bovine teeth as substitute for human teeth in dental research: a review of literature. Journal of oral science. 2011;53:273–282. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.53.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hara AT, Queiroz CS, Paes Leme AF, Serra MC, Cury JA. Caries progression and inhibition in human and bovine root dentine in situ. Caries Res. 2003;37:339–344. doi: 10.1159/000072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.