Abstract

The majority of individuals seeking treatment for substance use disorders are cigarette smokers, yet smoking cessation is rarely addressed during treatment. Conducting a detailed smoking-related characterization of substance abuse treatment patients across treatment modalities may facilitate the development of tailored treatment strategies. This study administered a battery of self-report instruments to compare tobacco use, quit attempts, smoking knowledge and attitudes, program services, and interest in quitting among smoking patients enrolled in opioid replacement therapy (ORT) vs. non-opioid replacement (non-ORT). ORT compared with non-ORT participants smoked more heavily, had greater tobacco dependence, and endorsed greater exposure to smoking cessation services at their treatment programs. Favorable attitudes towards cessation during treatment were found within both groups. These data identify several potential clinical targets, most notably including confidence in abstaining and attitudes toward cessation pharmacotherapies that may be addressed by substance abuse treatment clinics.

Keywords: smoking, knowledge, attitudes, program services, substance abuse treatment, S-KAS, quit interest, cessation

1. Introduction

The prevalence of tobacco use among substance abuse treatment program enrollees has been shown to be astonishingly high, with a number of studies demonstrating ranges of 75–97% (Bobo, 1989; Guydish et al., 2011a; Kalman, 1998; Nahvi et al., 2006; Pajusco et al., 2012). This is significantly higher than smoking rates in the general population, which is approximately 19.3% in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Those enrolled in substance abuse treatment are more likely to die due to smoking-related illnesses than from complications from their primary drug of choice (Baca & Yahne, 2009; Hser et al., 1994; Hurt et al., 1996). Despite high rates of smoking in substance abuse treatment patients, and the well-known health risks of smoking, the problem is generally not addressed in treatment clinics. Survey studies administered across treatment settings have reported estimates of smoking cessation services being offered in approximately 18% to 41% of programs that responded (Friedman et al., 2008; Fuller et al., 2007; Richter et al., 2004).

High rates of smoking and smoking-related illness among patients receiving treatment for substance use disorders has prompted several states and national organizations to encourage the development of smoking cessation interventions for these patients (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2008; New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services; Williams, 2008), which is consistent with the recommendations of the Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guidelines (Fiore et al., 2009). This approach is supported by studies suggesting that smoking cessation interventions during substance abuse treatment do not jeopardize and may even enhance long-term abstinence from drugs and alcohol (Bobo et al., 1998; Frosch et al., 2000; Hughes et al., 1993; Joseph et al., 1993; Prochaska et al., 2004; Richter & Arnsten, 2006; Tsoh et al., 2011). For example, among patients receiving treatment for substance use disorders, smoking abstinence at the end the first year of treatment was the most robust predictor of abstinence from illicit drug use at a 9-year follow-up (Tsoh et al., 2011), and a meta-analysis of smoking cessation in substance abusers reported a 25% increased likelihood of long-term drug abstinence among patients who also achieved smoking cessation (Prochaska et al., 2004). Substance abuse treatment centers also have the ability to provide smoking cessation resources. Patients generally attend the clinic frequently and for extended periods of time, which provides a unique opportunity to consistently monitor smoking, adjust smoking cessation strategies as needed, and generally implement an extended cessation intervention.

Understanding the smoking characteristics and cessation needs of patients receiving substance abuse treatment is critical for integrating cessation services into clinics. Smoking and cessation resources have been well-characterized among substance abuse treatment patients receiving methadone maintenance. Approximately 92% of methadone-maintained patients smoke cigarettes (Clemmey et al., 1997; Haas et al., 2008; Nahvi et al., 2006; Richter et al., 2001), 70–80% report an interest in quitting smoking, 68–75% have attempted to stop smoking at least once, and 75% report willingness to participate in a smoking cessation intervention if one were made available (Clemmey et al., 1997, Nahvi et al., 2006; Richter et al., 2001; Clarke et al., 2001; Frosch et al., 1998; Kozlowski et al., 1989; Sees & Clark, 1993). Frequent access to medical staff in methadone clinics has also been associated with increased availability of smoking cessation resources (Friedman et al., 2008) and more sustainable use of nicotine replacement therapy (Knudsen & Studts, 2011). However, several studies have reported that opioid agonists increase the reinforcing effects of cigarettes (Chait et al., 1984; Mello et al., 1980; Mello et al., 1985; Mutschuler et al., 2002; Schmitz et al., 1994), which suggests that opioid-dependent patients with continued use or who are receiving opioid replacement therapy (ORT) like methadone or buprenorphine maintenance may have different smoking profiles than those with non-opioid substance use. Thus, these data may not generalize to non-opioid maintained patients, and there is a dearth of current studies available to characterize smoking and interest in quitting among general substance abuse treatment patients. Further, interest in specific smoking cessation products has not been well-characterized in either population. Finally, although a recent review reported that smoking has generally decreased in ORT and non-opioid replacement therapy (non-ORT) patients over time (Guydish et al., 2011a), consistent with downward smoking trends evident in the general population, the results did not address the specific smoking characteristics and interest in quitting that might persuade substance abuse treatment clinics to offer smoking cessation resources to their patients.

The purposes of the current study were to characterize the smoking profile of substance abuse treatment patients receiving either ORT or non-ORT treatment services and to identify any potential differences among these patients, which may then inform smoking cessation treatment strategies. Demographic information, smoking characteristics, interest in quitting (and in the use of specific cessation products), perceived availability of cessation services offered by their substance abuse treatment program, and beliefs regarding whether smoking resources should be available during substance abuse treatment were surveyed.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants (N=266) were recruited from eight substance abuse treatment clinics in the Baltimore City metropolitan area, through posted fliers in clinic areas, word of mouth, and clinic staff. Recruitment took place between August of 2011 and June of 2012. Being a smoker was not required for study participation. The only criteria for participation were age older than 18 years and currently enrolled in substance abuse treatment (for any length of time). Eight participants failed to provide information on their medication status (methadone, buprenorphine, or neither) and were excluded from the data set. Among the remaining 258 participants, 203 (78.7%) were current smokers by self-report, with a higher percentage of smokers identified in ORT (85% compared to 74% of the non-ORT clinic sample; p = 0.01). All study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and were in accord with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Questionnaires were de-identified and participation was completely voluntary. Completion of the questionnaire served as consent.

2.2 Study Setting

All study sites were substance abuse treatment providers. Sites varied in the type and breadth of substance abuse treatment resources provided, with some study sites providing opioid replacement therapy only (N = 3 sites), some providing psychosocial counseling and non-ORT services only (N = 1 site) and the remainder providing both types of services (N = 4 sites). Participants recruited from each clinic represented a convenience sample and comprised only a proportion of the entire in-treatment population.

2.3 Survey Measures

Participants answered several questions designed to characterize demographics, substance abuse treatment details, and smoking information. Questionnaires included a locally-derived, self-report smoking measure that surveyed participant demographics, treatment status, current smoking status, history of quit attempts in the past year, and interest and confidence in quitting smoking. Due to evidence that methadone may increase the reinforcing effects of smoking and may therefore increase smoking rates (Chait et al., 1984; Mello et al., 1980; Mello et al., 1985; Mutschuler et al., 2002; Schmitz et al., 1994), several questions regarding smoking status before and after beginning treatment were included to assess whether treatment modality was associated with differential changes in smoking status during treatment. In addition, participants were asked which smoking cessation products they have used in the past (e.g., nicotine replacement, switching to low tar cigarettes or chewing tobacco, bupropion, varenicline), as well as what products they would be interested in trying, if offered. Not all products were evidence-based smoking cessation products and included options such as smokeless tobacco, special holders/filters, and electronic cigarettes.

Participants also completed the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton et al.,1991); a 6-item Confidence to Quit Questionnaire (Juliano et al., 2006); and the Smoking, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Services questionnaire (S-KAS; Guydish et al., 2011b; Guydish et al., 2012a). The S-KAS is a comprehensive self-report measure that assesses patient knowledge regarding the hazards of smoking (7 items), attitudes about smoking cessation in the context of substance abuse treatment (including the recommended timing of smoking cessation in relation to stopping drug use; 8 items), clinician services specific to promoting smoking cessation as part of substance abuse treatment, services provided, and clinician smoking cessation competence (7 items), and program services that assess smoking cessation services and resources provided at the treatment clinic, as well as policies and procedures consistent with smoking cessation (19 items). Reliability of the psychometric properties of this measurement, quantified through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α), were moderate to high for Knowledge (α=0.57), Attitudes (α=0.75), Clinician Services (α=0.82), and Program Services (α=0.82; Guydish et al., 2011b). Four individual S-KAS items believed to be of particular clinical relevance for programs trying to decide whether to offer smoking cessation services were analyzed separately; 1) should tobacco cessation be offered, 2) when is the best point to stop smoking, 3) have you been provided with any smoking cessation medications, and 4) is smoking cessation part of your personal treatment. S-KAS items were rated on 5-point Likert scales (1–5), and summed into 4 subscale scores (Knowledge, Attitudes, Clinician Services, and Program Services). Higher numbers indicated greater knowledge, favorable smoking cessation attitudes, as well as clinician and program services that promoted smoking cessation.

Questionnaires were self-administered either via paper and pencil surveys (72%) or computer (28%). Participants were given either $5 or a small prize for survey completion. Additional items on the questionnaire not included in this report asked about communication technology use (McClure et al., 2013) and second-hand smoke exposure (Acquavita et al., In Preparation).

2.4 Data Analysis

Only data from current smokers were analyzed for this report (N=203 out of 258). Data were analyzed using mixed models in IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 to account for the random effects of clinic (8 different sites) on dependent variables. Linear mixed models were used for continuous variables, while generalized linear mixed models were used for categorical variables. These types of models are ideal for analyzing clustered data (McCulloch & Searle, 2001). The fixed factor for all analyses was substance abuse treatment modality (ORT vs. non-ORT), and clinic was used as a random effect. Methadone (N=64) and buprenorphine-maintained (N=33) patients were collapsed together for the ORT group. Dependent variables included demographics, smoking characteristics, interest in quitting, and S-KAS scores, comparing ORT and non-ORT participants. S-KAS analyses were restricted to participants that had been enrolled in a treatment program for at least 2 weeks, to allow them ample time to have come into contact with smoking cessation services, based upon guidelines from Guydish et al. (2011b). Therefore, for the S-KAS analysis, 10% of ORT and 15% of non-ORT participants were excluded from those analyses. Results were averaged into subscale values and compared between ORT and non-ORT participants. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α) for the Knowledge, Attitudes, Clinical, and Program Services scales from the current data set were 0.39, 0.58, 0.78, and 0.83 respectively.

3. Results

3.1 Participants

Demographic information from this survey study has been reported elsewhere (McClure et al., 2013), and is presented in Table 1 for smokers only as a function of ORT (N=97) and non-ORT (N=106) treatment modality. No demographic differences existed across treatment modality, though gender approached significance (p=0.07). Non-ORT participants were more likely to report better health status (p=.003) as compared to ORT participants. Self-reported primary substance of abuse was evenly distributed amongst patients enrolled in non-ORT treatment. Rates of other substance use across both treatment modalities was reported in 17% of the entire sample for alcohol, 31% for stimulants, 8% for marijuana, 15% for opiates, and 3% for other drugs (i.e. hallucinogens, benzodiazepines, sedatives, etc.).

Table 1.

Demographics of smokers only as a function of treatment modality

| Treatment Modality | ORT (N=97) |

Non-ORT (N=106) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Years (SD) | p value | ||

| Age | 45 (11) | 43 (11) | 0.6 |

| % (N) | p value | ||

| Gender | (96) | (103) | 0.07 |

| Male | 54 | 69 | |

| Female | 46 | 29 | |

| Transgender | 0 | 2 | |

| Race | (93) | (100) | 0.2 |

| AA/Black | 57 | 80 | |

| White | 36 | 19 | |

| Other | 7 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | (95) | (103) | 0.7 |

| Latino | 1 | 3 | |

| Relationship Status | (94) | (101) | 0.5 |

| Married/Long-term relationship | 40 | 34 | |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 26 | 29 | |

| Never Married | 34 | 37 | |

| Education | (96) | (103) | 0.6 |

| Less than HS Diploma | 47 | 40 | |

| HS/GED | 31 | 39 | |

| Some College or more | 22 | 21 | |

| Employment | (97) | (106) | 0.6 |

| Unemployed | 39 | 35 | |

| Full/Part time or Student | 42 | 50 | |

| Retired or Disability | 19 | 15 | |

| Annual Income | (95) | (103) | 0.9 |

| < $15,000 | 58 | 59 | |

| $15,000 – $29,999 | 24 | 24 | |

| ≥ $30,000 | 18 | 17 | |

| Counseling Intensity | (97) | (106) | 0.9 |

| IOP | 42 | 43 | |

| OP | 58 | 57 | |

| ORT Medication | (97) | - | |

| Methadone | 66 | - | |

| Buprenorphine | 34 | - | |

| Primary Drug of Abuse | (96) | (98) | <.001 |

| Alcohol | 4 | 25 | |

| Stimulants | 4 | 26 | |

| Marijuana | 0 | 18 | |

| Opiates | 89 | 31 | |

| Other | 3 | 0 | |

| Health Status | (95) | (101) | 0.003 |

| Excellent | 5 | 16 | |

| Very Good | 18 | 29 | |

| Good | 29 | 33 | |

| Fair | 43 | 16 | |

| Poor | 5 | 6 | |

Note: Demographics for smokers only are split by opioid replacement therapy (ORT) and non-opioid replacement (non-ORT). Intensive outpatient (IOP) includes nine or more hours of scheduled treatment per week. Outpatient (OP) refers to fewer than nine scheduled hours per week. Significant treatment group differences determined via linear and generalized linear mixed models with clinic site defined as a random effect.

3.2 Smoking Characteristics

Current and previous tobacco use is shown as a function of treatment modality in Table 2. ORT participants reported significantly higher FTND scores (5.1 vs. 4.2, respectively, p=.002), more cigarettes per day (12.9 vs. 10.6, respectively, p=.05), and more cigarettes smoked per day prior to entering treatment (14.2 vs. 11.0, respectively, p=.04). Otherwise, the two groups were similar on several smoking-related characteristics, including use of alternative tobacco products, age at which they began smoking cigarettes regularly, and number of days smoked per week prior to entering treatment. Across both treatment types, 47% of participants reported no change in their smoking since entering substance abuse treatment, with 25% reporting smoking more since entering substance abuse treatment, and 28% reporting smoking less.

Table 2.

Smoking characteristics as a function of treatment modality

| % (N)/Mean (SD) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ORT | Non-ORT | ||

| FTND | (81) | (91) | 0.002 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) | |

| Cigarettes/day | (96) | (106) | 0.05 |

| Mean (SD) | 12.9 (7.4) | 10.6 (5.7) | |

| Use of other tobacco products ever? | (96) | (101) | 0.1 |

| Cigars | 15 | 14 | |

| Smokeless tobacco | 5 | 2 | |

| E-cigarettes | 26 | 14 | |

| SNUS | 1 | 1 | |

| Menthol cigarettes | (58) | (64) | 0.04 |

| Mentholated | 81 | 92 | |

| Non-mentholated | 19 | 8 | |

| Age of regular smoking | (96) | (103) | 0.3 |

| Mean (SD) | 15.8 (5) | 16.6 (6) | |

| Days/week of smoking before treatment | (97) | (106) | 0.5 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.4 (1.5) | 6.3 (1.5) | |

| Cigarettes/day before treatment | (93) | (102) | 0.04 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.2 (9.6) | 11.0 (5.9) | |

| Smoking changes since entering treatment | (95) | (102) | 0.2 |

| Smoke more | 31 | 19 | |

| Smoke less | 24 | 32 | |

| Smoke the same | 45 | 49 | |

Note: Significant treatment group differences determined via linear and generalized linear mixed models with clinic site defined as a random effect.

3.3 Quit Attempts and Interest in Quitting

Ratings of previous quit attempts, desire to quit smoking, and confidence to abstain from cigarettes once quit are shown in Table 3. Despite differences in FTND scores and cigarettes per day across treatment modality, no significant between-group differences were observed in number of quit attempts in the past year. The majority of ORT and non-ORT participants reported making both voluntary and forced (e.g., incarceration, hospitalization, or residential treatment facility) quit attempts that lasted at least 24 hours in the past year. Participants in both groups also reported moderate desire to quit smoking (3.3 out of 6) and 29% of participants reported that they were seriously considering a quit attempt within the next 30 days. However, both groups reported low confidence in their ability to abstain from cigarettes for 24 hours up to one month.

Table 3.

Quit interest and characteristics as a function of treatment modality for smokers only

| % (N)/Mean (SD) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ORT | Non-ORT | ||

| Voluntary quit attempts (24+ hours) | (87) | (99) | 0.6 |

| One or more times - % | 59 | 55 | |

| Forced quit attempts (24+ hours) | (87) | (97) | 0.7 |

| One or more times - % | 72 | 69 | |

| Considering quitting in the next 30 days? | (87) | (101) | 0.9 |

| Yes - % | 29 | 30 | |

| Desire to quit smoking now | (95) | (104) | 0.1 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.1) | 3.6 (2.1) | |

| Confidence you can quit at this time | (94) | (103) | 0.5 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.8) | 2.6 (2.0) | |

| Confidence – abstain for 24 hours | (94) | (103) | 0.1 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.9) | 2.6 (2.2) | |

| Confidence – abstain for 1 month | (94) | (102) | 0.6 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.8) | 1.7 (2.0) | |

Note: Significant treatment group differences determined via linear and generalized linear mixed models with clinic site defined as a random effect (none found). Desire to quit and confidence ratings ranged from 0 to 6 (0 = not at all confident, 6 = extremely confident).

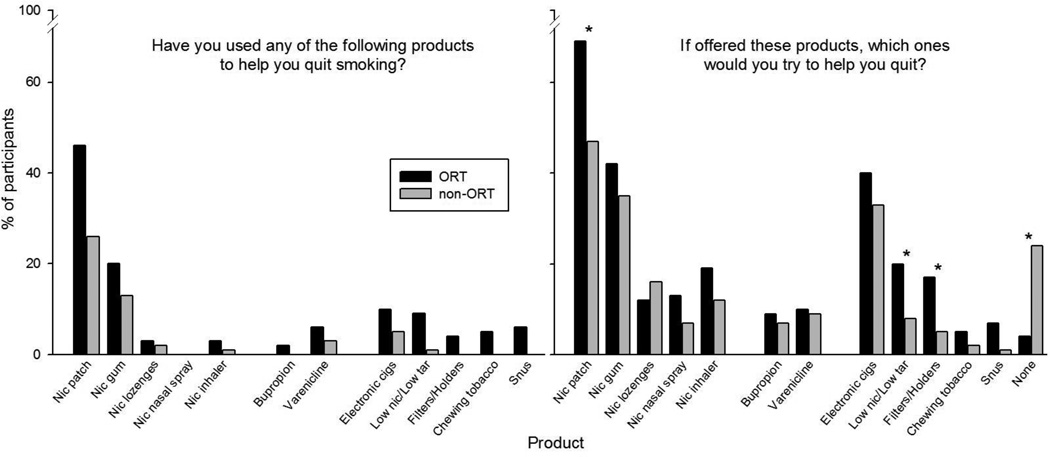

The use of various products that participants have tried in the past to help them quit smoking (lifetime) is shown in the left panel of Figure 1. Not all products listed were smoking cessation products and included use of and interest in smokeless tobacco, special holders/filters, and electronic cigarettes. Nicotine patch was by far the most commonly used cessation product in previous quit attempts among the study sample. Slightly more ORT than non-ORT participants reported previous use of the patch, though this result only approached significance (p=0.06). Participants also expressed interest in trying these and other products in the future, as shown in the right panel of Figure 1. ORT participants expressed more enthusiasm than did non-ORT participants about trying both the nicotine patch and other products to help them quit smoking (p < .05)

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants endorsing products used at least once to assist in their quit attempts (left panel), and percentage of participants endorsing products that they would be interested in using to help them quit smoking (right panel). Asterisks indicate a p-value of < 0.05 between ORT and non-ORT groups with clinic site defined as a random effect.

3.4 Smoking Knowledge, Attitudes, Clinician, and Program Services (S-KAS)

As shown in Table 4, ORT and non-ORT participants had largely similar ratings on the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Clinician Services subscales of the S-KAS instrument. Knowledge and Attitudes were moderate across patient populations. Program services, however, received much lower ratings and ORT participants rated their treatment programs higher compared to non-ORT participants (p<0.001), indicating services and policies consistent with treating tobacco dependence.

Table 4.

S-KAS scale ratings

| (N)/Mean (SD) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S-KAS subscales (1–5) | ORT | Non-ORT | |

| Knowledge | (86) | (87) | 0.9 |

| 3.48 (0.57) | 3.49 (0.62) | ||

| Attitudes | (86) | (88) | 0.06 |

| 3.46 (0.67) | 3.25 (0.74) | ||

| Clinician Services | (80) | (81) | 0.9 |

| 2.30 (0.96) | 2.16 (1.09) | ||

| Program Services | (87) | (88) | <0.001 |

| 2.73 (0.91) | 2.13 (0.72) | ||

Note: Knowledge, Attitudes, Clinician and Program services sub-scales were rated from 1 to 5. Higher numbers indicated greater knowledge, pro-smoking cessation attitudes, and clinician and program services that promoted smoking cessation. Each subscale included the following number of items: Knowledge (N=7), Attitudes (N=8), Clinician Services (N=7), Program Services (N=19). Significant group differences determined via linear mixed models with clinic site defined as a random effect.

Four S-KAS items that may be of particular clinical relevance for substance abuse treatment programs are shown in Table 5. The majority of participants, independent of treatment modality, agreed that smoking cessation should be offered in their treatment program and currently was not part of their personal substance abuse treatment plan. Nearly half of the participants also felt that the best time to stop smoking was before or at the same time as stopping drug use (47%). Finally, ORT participants were more likely to have been provided with at least one smoking cessation medication through their treatment program (22% vs 4%; p<0.001).

Table 5.

Specific Attitudes and Program Services S-KAS items

| % (N) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ORT | Non-ORT | ||

| Should tobacco cessation be offered? | (86) | (84) | 0.1 |

| Yes | 87 | 77 | |

| No | 13 | 23 | |

| When is the best point to stop smoking? | (82) | (84) | 0.3 |

| Before/Same time as stopping drug use | 43 | 51 | |

| After 6 months | 22 | 27 | |

| After 1 year | 24 | 12 | |

| After 5 years | 5 | 3 | |

| Never | 6 | 7 | |

| Were you provided with any smoking cessation meds? | (85) | (86) | <0.001 |

| At least 1 med | 22 | 4 | |

| No meds | 78 | 96 | |

| Is smoking cessation part of your personal treatment? | (82) | (84) | 0.07 |

| Yes | 15 | 6 | |

| No | 85 | 94 | |

Note: Significant group differences determined via generalized linear mixed models with clinic site defined as a random effect.

4. Discussion

These data highlight important differences that exist between substance abuse treatment patients receiving ORT compared to patients not receiving ORT, and provide the first detailed characterization of smoking among non-ORT patients. Overall, both groups had high rates of smoking, though ORT participants were more likely to be smokers, smoked more heavily, and were more tobacco dependent (based on FTND scores). ORT participants tended to report more past experience with smoking cessation and other products compared to non-ORT participants, though these rates were generally low and not statistically different. This trend is not surprising given that ORT treatment is a modality where patients are taking a therapeutic medication to reduce craving and withdrawal symptoms in order to maintain long-term abstinence. ORT patients are also exposed to medical personnel during treatment, which is a program characteristic that predicts the availability of smoking cessation resources (Friedman et al., 2008). Several other program and staff characteristics that predict smoking cessation treatment have been identified in the literature, which may be applicable to ORT treatment patients as well. Hospital-affiliated clinics are more likely to provide smoking cessation pharmacotherapy and more evidence-based practices (Knudsen & Studts, 2011; Tajima et al., 2009), potentially due to staff characteristics that predict more favorable smoking cessation attitudes (i.e. lower smoking rates among staff, higher education level; Tajima et al., 2009).

The current report also found that ORT participants showed greater interest in trying various smoking cessation products In contrast, non-ORT participants reported lower willingness to try new products, including 24% who specifically endorsed no interest in using any smoking cessation product. This willingness to try new products among ORT participants may reflect a more pro-medication attitude and more openness to strategies utilizing pharmacotherapies. This finding may be a result of the influence of staff knowledge and attitudes regarding smoking cessation resources, the specific organization and their mission as it relates to general health, exposure to medical staff regularly, and/or the patient’s perceptions of substance abuse and medications to maintain abstinence. The complex relationship between organization, staff, and patient in terms of smoking cessation should be further explored, as well as the pro-medication attitude as this finding is novel and important because it represents a potential clinical target for non-ORT patients.

The current data reveal that patients are also interested in trying non-evidence based strategies, indicating that both patients and staff may require information on effective strategies for cessation. For example, approximately 37% of participants from both groups reported interest in using electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) for cessation. E-cigarettes have not been demonstrated as an evidence-based cessation approach; however, non-substance abusing individuals are utilizing e-cigarettes for cessation purposes (Goniewicz et al., 2012). Interest in adopting any method of smoking cessation treatment during a quit attempt in a substance abuse treatment population is an area that warrants further investigation. Among the general population of smokers, those who are more nicotine dependent have been shown to adopt treatment during a quit attempt (Shiffman et al., 2008a; Shiffman et al., 2008b). More heavily dependent smokers are at the greatest risk for relapse, and may have had several unassisted and failed quit attempts in the past, thus prompting the adoption of treatment. Shiffman et al. (2008a) also showed that the use of alternative treatments for smoking cessation (hypnosis and acupuncture) was higher among those who had been smoking for more than 15 years. These results are applicable to a substance abuse treatment population, and specifically those maintained on opioid replacement, as they represent a highly nicotine dependent group with a long history of regular smoking. Interest or preference in alternative treatments among substance abuse treatment patients may result from several unsuccessful quit attempts, greater accessibility to alternative treatments, and lower costs. More research is needed regarding the value of non-evidence based strategies to promote cessation attempts or reduce harm, as these products may be well-received by both ORT and non-ORT patients. However, in lieu of those data, clinics can potentially improve cessation outcomes by helping patients discriminate between cessation strategies supported and unsupported by evidence.

ORT patients endorsed more services offered through their treatment programs. Along with organization and staff characteristics mentioned above, ORT treatment models generally provide a longer duration of contact. In contrast, treatment participation is generally of shorter duration in non-ORT programs, which may shift focus toward prioritizing treatment of the primary substance of abuse. Also, there may not be adequate time for staff to be effective in promoting quit attempts. Differences in treatment philosophies and clinic culture are also likely to impact views about the adoption of smoking cessation medications in programs that follow approaches closely resembling 12-step programs (Rothrauff & Eby, 2010). Overall, our data suggest that non-ORT patients are at a serious service-level disadvantage when it comes to smoking cessation support. Although differences in treatment modalities and approaches provide different opportunities to target cessation, a variety of brief and immediate approaches, such as motivational techniques, cessation product education, or sampling, could be used for cessation in non-ORT patients. Motivational techniques may be particularly important and necessary, as evidenced by low confidence ratings for successful smoking cessation in both patient subgroups. Interventions designed to boost confidence or experience with abstinence through contingent incentives (Dunn et al., 2011) may be useful along with smoking cessation medications for smokers in substance abuse treatment.

Consistent with data suggesting that opioid agonists increase the reinforcing effects of smoking, ORT patients reported smoking more cigarettes per day than non-ORT patients prior to entering treatment and continued to smoke at higher rates while enrolled in treatment. Overall, neither group showed a pattern of increasing or decreasing the amount smoked after treatment entry. These data indicate that despite receiving specialized medical attention in the form of substance abuse treatment, entry into treatment does not decrease smoking rates. The frequent clinical contact and long duration of treatment that is generally provided in substance abuse settings represents an ideal and unique opportunity to target smoking cessation resources. The fact that entry into treatment was not associated with reductions in smoking highlights the need to systematically address smoking cessation within treatment settings.

The S-KAS measurement items indicated substantial knowledge and favorable smoking cessation attitudes in the current study sample, which is consistent with previous reports from methadone-maintained populations (Clemmy et al., 1997; Nahvi et al., 2006). Lower ratings of services availability is also consistent with recent reports in which service provision was evaluated in substance abuse treatment clinics that varied in geographic location and sample population (Guydish et al., 2012a; Guydish et al., 2012b). Importantly, those reports found that organizational change, either through policy or intervention, led to overall improvements in patient attitudes towards smoking cessation, as well as ratings of program and clinician services.

Several barriers exist that complicate the implementation of smoking cessation services into substance abuse treatment clinics, such as; limited staff training and lack of knowledge of smoking cessation techniques, limited financial resources for smoking cessation, resistance from staff, the belief that a smoking intervention could have a negative impact on drug treatment, lack of client interest in quitting smoking, and counselors themselves being smokers and not addressing smoking with their clients (Asher et al., 2003; Bobo, 1989; Bobo & Davis, 1993; Campbell et al., 1998; Guydish et al., 2007; Hahn et al., 1999; Hurt et al., 1996; Knudsen et al., 2010; Sees & Clark, 1993; Sussman, 2002; Walsh et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2005; Ziedonis et al., 2006). There is ample justification, however, to invest the time and resources into overcoming these barriers in order to provide smoking cessation services to substance abuse patients. Evidence in the literature has shown that anywhere from 44% to 80% of substance abuse treatment patients want to quit smoking during a treatment episode (Ellingstad et al., 1999; Nahvi et al., 2006; Richter & Ahluwalia, 2000; Richter et al., 2001; Sees & Clark, 1993; Zullino et al., 2000). Among the current data set, 29% reported seriously considering making a quit attempt within the subsequent 30 days. It has also been demonstrated that smoking cessation interventions during substance abuse treatment do not jeopardize and may even enhance long-term abstinence from drugs and alcohol (Bobo et al., 1998; Joseph et al., 1993; Prochaska et al., 2004; Richter & Arnsten, 2006; Tsoh et al., 2011).

This study has several limitations that should be noted. First, participants completing the survey consisted of a convenience sample from urban substance abuse treatment clinics and may not have been representative of all clinic patients. This may diminish generalizability of our findings to other treatment samples. Second, participating clinics had varying characteristics, location, and smoking policies, which were not directly assessed in this study. Given clinic differences and patient characteristics across sites, the statistical plan in this report treated clinic site as a random effect. Treatment modality differences were still detected when accounting for clinic site, but the specific characteristics of the clinic should be assessed in future work as those may influence patient responses. Third, questions regarding cessation products did not ask about counseling or quit line assistance, and it is also possible that products may not have been endorsed because patients had never heard of them. Fourth, no treatment level data were obtained, which prevents us from determining whether smoking or interest in quitting varied as a function of ongoing illicit drug use during treatment for primary substances or other substances used, or whether treatment was mandated or voluntary. Further, we were not able to determine if the route of administration of the primary or other substances of abuse influenced survey responses (i.e. inhalation vs. injection, etc.). It may be that those who use other drugs that are inhaled would vary in their smoking characteristics and attitudes towards cessation. Finally, missing data were a problem in this study. Many questionnaires were administered via paper and pencil and research staff could not always verify completion and consistency across responses. Surveys administered on computers included skip patterns so that respondents were only answering relevant questions, and also reminded participants if they had missed a question. For this reason, computer-delivered survey administration was preferable, but not always feasible or popular among study participants.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a detailed and comprehensive characterization of smoking attitudes in ORT and non-ORT patients. The data obtained regarding ORT patients is consistent with previous reports, which strengthens the likelihood our results will generalize to the larger substance abusing population. Importantly, these data identify several potential clinical targets, most notably including confidence in abstaining and attitudes toward the availability of cessation products that can be addressed by substance abuse treatment clinics. The pro-medication attitude and openness to pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation among ORT patients should be greater utilized to promote improved smoking cessation knowledge, attitudes, and treatment practices among staff and should be encouraged in non-ORT treatment models. Tailored program interventions across treatment modalities may include increased access to cessation products for ORT, while non-ORT services may need to focus on motivation and educational information to promote interest and sampling of cessation products. This approach would be consistent with Clinical Practice Guidelines for tobacco dependence and several state and organization recommendations, and would help decrease the tobacco-related morbidity and mortality in this population.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Joseph Guydish, Kevin Delucchi, and Barbara Tajima for the approved use of the S-KAS measurement and for their input on study implementation and analyses. We thank Corey Molzon, Leanne Simington, Jasmine Dixon, Rajni Sharma, Wendy Parker, and Samuel King for their hard work on survey administration and data entry. We thank the directors and staff of the participating clinics: Harbel Prevention and Recovery, The Broadway Center, the Johns Hopkins Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit clinic, Tuerk House, Cornerstone, Comprehensive Care, Mountain Manor, and Addiction Treatment Services. We also thank the Biostatistics section of the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research at the Medical University of South Carolina for support with data analyses.

Role of Funding Source. Funding for this study was provided by the NIDA training grant (T32 DA07209) and the Clinical Trials Network – Mid-Atlantic node (U10 DA13034) at the Johns Hopkins University, as well as by the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Institute at the Medical University of South Carolina (UL1TR000062) from the National Center for Research Resources. Additional support was provided by NIDA grants U01DA031779 and U10DA013727 at the Medical University of South Carolina. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors. All authors contributed to the design and execution of the study, analyses of data, and manuscript preparation. All authors have approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Notes. This work was conducted at the Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. The corresponding author now holds a position with the Clinical Neuroscience Division at the Medical University of South Carolina School of Medicine.

References

- Acquavita SP, McClure EA, Hargraves D, Stitzer ML. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure for individuals receiving outpatient substance abuse treatment. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.016. In preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Public policy statement on nicotine addiction and tobacco (formally nicotine dependence and tobacco) Chevy Chase, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Asher MK, Martin RA, Rohsenow DJ, MacKinnon SV, Traficante R, Monti PM. Perceived barriers to quitting smoking among alcohol dependent patients in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca CT, Yahne CE. Smoking cessation during substance abuse treatment: What you need to know. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36(2):205–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK. Nicotine dependence and alcoholism epidemiology and treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1989;21(3):323–329. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1989.10472174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Davis CM. Recovering staff and smoking in chemical dependency programs in rural nebraska. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10(2):221–227. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, McIlvain HE, Lando HA, Walker RD, Leed-Kelly A. Effect of smoking cessation counseling on recovery from alcoholism: Findings from a randomized community intervention trial. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 1998;93(6):877–887. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9368779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BK, Krumenacker J, Stark MJ. Smoking cessation for clients in chemical dependence treatment - A demonstration project. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15(4):313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Quitting smoking among adults--united states, 2001–2010. MMWR.Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60(44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chait LD, Griffiths RR. Effects of methadone on human cigarette smoking and subjective ratings. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1984;229(3):636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JG, Stein MD, McGarry KA, Gogineni A. Interest in smoking cessation among injection drug users. The American Journal on Addictions / American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions. 2001;10(2):159–166. doi: 10.1080/105504901750227804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmey P, Brooner R, Chutuape MA, Kidorf M, Stitzer M. Smoking habits and attitudes in a methadone maintenance treatment population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;44(2–3):123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. public health service report. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35(2):158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KE, Saulsgiver KA, Sigmon SC. Contingency management for behavior change: Applications to promote brief smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;19(1):20–30. doi: 10.1037/a0022039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingstad TP, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Cleland PA, Agrawal S. Alcohol abusers who want to quit smoking: Implications for clinical treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;54(3):259–265. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M, Jaen C, Baker T, Bailey W, Benowitz N, Currie S, et al. Clinical practice guideline. treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Jiang L, Richter KP. Cigarette smoking cessation services in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs in the united states. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch DL, Shoptaw S, Jarvik ME, Rawson RA, Ling W. Interest in smoking cessation among methadone maintained outpatients. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1998;17(2):9–19. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch DL, Shoptaw S, Nahom D, Jarvik ME. Associations between tobacco smoking and illicit drug use among methadone-maintained opiate-dependent individuals. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8(1):97–103. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller BE, Guydish J, Tsoh J, Reid MS, Resnick M, Zammarelli L, … McCarty D. Attitudes toward the integration of smoking cessation treatment into drug abuse clinics. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, Chan M, Chun J, Bostrom A. Smoking prevalence in addiction treatment: A review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research : Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2011a;13(6):401–411. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, Manser ST. Staff smoking and other barriers to nicotine dependence intervention in addiction treatment settings: A review. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(4):423–433. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Tajima B, Chan M, Delucchi KL, Ziedonis D. Measuring smoking knowledge, attitudes and services (S-KAS) among clients in addiction treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011b;114(2–3):237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Tajima B, Kulaga A, Zavala R, Brown LS, Bostrom A, … Chan M. The new york policy on smoking in addiction treatment: Findings after 1 year. American Journal of Public Health. 2012a;102(5):e17–25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Ziedonis D, Tajima B, Seward G, Passalacqua E, Chan M, … Brigham G. Addressing tobacco through organizational change (ATTOC) in residential addiction treatment settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012b;121(1–2):30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Sorensen JL, Hall SM, Lin C, Delucchi K, Sporer K, Chen T. Cigarette smoking in opioid-using patients presenting for hospital-based medical services. The American Journal on Addictions / American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions. 2008;17(1):65–69. doi: 10.1080/10550490701756112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EJ, Warnick TA, Plemmons S. Smoking cessation in drug treatment programs. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1999;18(4):89–101. doi: 10.1300/J069v18n04_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, McCarthy WJ, Anglin MD. Tobacco use as a distal predictor of mortality among long-term narcotics addicts. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23(1):61–69. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Treatment of smoking cessation in smokers with past alcohol/drug problems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10(2):181–187. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, Morse RM, Melton LJ., 3rd Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275(14):1097–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.14.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Nichol KL, Anderson H. Effect of treatment for nicotine dependence on alcohol and drug treatment outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 1993;18(6):635–644. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano LM, Donny EC, Houtsmuller EJ, Stitzer ML. Experimental evidence for a causal relationship between smoking lapse and relapse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(1):166–173. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman D. Smoking cessation treatment for substance misusers in early recovery: A review of the literature and recommendations for practice. Substance use & Misuse. 1998;33(10):2021–2047. doi: 10.3109/10826089809069815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Studts JL. Availability of nicotine replacement therapy in substance use disorder treatment: Longitudinal patterns of adoption, sustainability, and discontinuation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118(2–3):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Studts JL, Boyd S, Roman PM. Structural and cultural barriers to the adoption of smoking cessation services in addiction treatment organizations. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2010;29(3):294–305. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2010.489446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Skinner W, Kent C, Pope MA. Prospects for smoking treatment in individuals seeking treatment for alcohol and other drug problems. Addictive Behaviors. 1989;14(3):273–278. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, Acquavita SP, Harding E, Stitzer ML. Utilization of communication technology by patients enrolled in substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;129(1–2):145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch C, Searle SR. Generalized, linear, and mixed models. New York, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH. Buprenorphine effects on cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology. 1985;86(4):417–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00427902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Sellers ML, Kuehnle JC. Effects of heroin self-administration on cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology. 1980;67(1):45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00427594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutschler NH, Stephen BJ, Teoh SK, Mendelson JH, Mello NK. An inpatient study of the effects of buprenorphine on cigarette smoking in men concurrently dependent on cocaine and opioids. Nicotine & Tobacco Research : Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2002;4(2):223–228. doi: 10.1080/14622200210124012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahvi S, Richter K, Li X, Modali L, Arnsten J. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting in methadone maintenance patients. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(11):2127–2134. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services. NY state leads the nation with tobacco-free initiative to enhance recovery and save lives. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Pajusco B, Chiamulera C, Quaglio G, Moro L, Casari R, Amen G, … Lugoboni F. Tobacco addiction and smoking status in heroin addicts under methadone vs. buprenorphine therapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2012;9(3):932–942. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Delucchi K, Hall SM. A meta-analysis of smoking cessation interventions with individuals in substance abuse treatment or recovery. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1144–1156. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Ahluwalia JS. A case for addressing cigarette use in methadone and other opioid treatment programs. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2000;19(4):35–52. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Arnsten JH. A rationale and model for addressing tobacco dependence in substance abuse treatment. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2006;1:23. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Choi WS, Alford DP. Smoking policies in U.S. outpatient drug treatment facilities. Nicotine & Tobacco Research : Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2005;7(3):475–480. doi: 10.1080/14622200500144956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Choi WS, McCool RM, Harris KJ, Ahluwalia JS. Smoking cessation services in U.S. methadone maintenance facilities. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) 2004;55(11):1258–1264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Gibson CA, Ahluwalia JS, Schmelzle KH. Tobacco use and quit attempts among methadone maintenance clients. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(2):296–299. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothrauff TC, Eby LT. Counselors’ knowledge of the adoption of tobacco cessation medications in substance abuse treatment programs. The American Journal on Addictions / American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions. 2011;20(1):56–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Grabowski J, Rhoades H. The effects of high and low doses of methadone on cigarette smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;34(3):237–242. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sees KL, Clark HW. When to begin smoking cessation in substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10(2):189–195. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Individual differences in adoption of treatment for smoking cessation: Demographic and smoking history characteristics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008a;93(1–2):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the united states. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008b;34(2):102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S. Smoking cessation among persons in recovery. Substance use & Misuse. 2002;37(8–10):1275–1298. doi: 10.1081/ja-120004185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima B, Guydish J, Delucchi K, Passalacqua E, Chan M, Moore M. Staff knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding nicotine dependence differ by setting. Journal of Drug Issues. 2009;39(2):365–384. doi: 10.1177/002204260903900208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoh JY, Chi FW, Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Stopping smoking during first year of substance use treatment predicted 9-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114(2–3):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RA, Bowman JA, Tzelepis F, Lecathelinais C. Smoking cessation interventions in australian drug treatment agencies: A national survey of attitudes and practices. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2005;24(3):235–244. doi: 10.1080/09595230500170282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM. Eliminating tobacco use in mental health facilities: Patients' rights, public health, and policy issues. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(5):571–573. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Foulds J, Dwyer M, Order-Connors B, Springer M, Gadde P, Ziedonis DM. The integration of tobacco dependence treatment and tobacco-free standards into residential addictions treatment in new jersey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(4):331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziedonis DM, Guydish J, Williams J, Steinberg M, Foulds J. Barriers and solutions to addressing tobacco dependence in addiction treatment programs. Alcohol Research & Health : The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2006;29(3):228–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zullino D, Besson J, Schnyder C. Stage of change of cigarette smoking in alcohol-dependent patients. European Addiction Research. 2000;6(2):84–90. doi: 10.1159/000019015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]