Abstract

Intrapleural processing of prourokinase (scuPA) in tetracycline (TCN)-induced pleural injury in rabbits was evaluated to better understand the mechanisms governing successful scuPA-based intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy (IPFT), capable of clearing pleural adhesions in this model. Pleural fluid (PF) was withdrawn 0–80 min and 24 h after IPFT with scuPA (0–0.5 mg/kg), and activities of free urokinase (uPA), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and uPA complexed with α-macroglobulin (αM) were assessed. Similar analyses were performed using PFs from patients with empyema, parapneumonic, and malignant pleural effusions. The peak of uPA activity (5–40 min) reciprocally correlated with the dose of intrapleural scuPA. Endogenous active PAI-1 (10–20 nM) decreased the rate of intrapleural scuPA activation. The slow step of intrapleural inactivation of free uPA (t1/2β = 40 ± 10 min) was dose independent and 6.7-fold slower than in blood. Up to 260 ± 70 nM of αM/uPA formed in vivo [second order association rate (kass) = 580 ± 60 M−1·s−1]. αM/uPA and products of its degradation contributed to durable intrapleural plasminogen activation up to 24 h after IPFT. Active PAI-1, active α2M, and α2M/uPA found in empyema, pneumonia, and malignant PFs demonstrate the capacity to support similar mechanisms in humans. Intrapleural scuPA processing differs from that in the bloodstream and includes 1) dose-dependent control of scuPA activation by endogenous active PAI-1; 2) two-step inactivation of free uPA with simultaneous formation of αM/uPA; and 3) slow intrapleural degradation of αM/uPA releasing active free uPA. This mechanism offers potential clinically relevant advantages that may enhance the bioavailability of intrapleural scuPA and may mitigate the risk of bleeding complications.

Keywords: fibrinolytic therapy, rabbit model, pleural injury, urokinase, α-macroglobulin, human

fibrinolysins, including tissue type (tPA) and urokinase (active two-chain enzyme; tcuPA), are plasminogen activators (PAs) that have long been used to treat a variety of thrombotic conditions including acute myocardial infarction (23; 44), deep vein thrombosis (33, 40), ischemic stroke (1, 3), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (20, 21), pulmonary emboli, and organizing pleural effusions (8, 9, 11, 31, 37, 43). Although intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy (IPFT) has been in use for over 60 years, it has recently undergone reassessment in light of the disparate results seen in clinical trials (9, 11, 37). The efficacy of IPFT in adults remains a subject of ongoing debate. Intrapleural streptokinase was ineffective in patients with complicated parapneumonic pleural effusions and empyema (EMP), whereas other IPFT clinical trials demonstrated efficacy (9, 37). More recently, the Second Multicenter Intrapleural Sepsis Trial (MIST2) demonstrated that IPFT with tPA alone at a 10-mg intrapleural unit dose did not improve clinical outcome in adult patients with complicated pleural infections (11, 43), whereas a recent randomized trial of uPA-based IPFT showed a decrease in the rate of surgical intervention in children with EMP and pleural loculations (13).

It is clear that intrapleural processing of fibrinolysins is complex and can be influenced by a variety of factors. In this regard, the role of proteinase-inhibitor interactions is critical to fibrinolysin function within the pleural space (26, 32). Increased levels of antigen and activity of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) in virtually all forms of pleural injury contribute to impaired fibrin turnover and promote pleural loculation (12, 27–30, 32, 41, 47). Active PAI-1 is one of the most important profibrogenic molecules and a promising target for IPFT (32). PAI-1 rapidly inhibits tPA and tcuPA [second order association rate (kass) > 106 M−1·s−1] (24, 53) but slowly inactivates single-chain uPA (scuPA) (35), making the latter a potentially advantageous agent for IPFT (27). In the airway and pleural fluids (PFs), uPA forms complexes with α-macroglobulins (αM) (35, 36). In humans, α2M (5, 7, 48) is a major secondary endogenous proteinase inhibitor with broad specificity; its concentration in serum approaches 1–2 mg/ml, which is much higher than that of PAI-1 (6). Conformational changes trap the proteinase molecule inside a “molecular cage” complex formed by two subunits of α2M (42). At the same time an encrypted binding site for α2M receptor/low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) becomes exposed and α2M gains the ability to interact with its receptor (51). The binding of α2M/enzyme to LRP results in endocytosis of the proteinase (15, 18). In contrast to inactivation by serpins, which results in a complete loss of enzymatic activity due to the stabilization of the acyl-enzyme intermediate, proteinases complexed with α2M are active toward low molecular weight (LMW) substrates, indicating the preservation of the enzyme's machinery. Although the inhibition of endogenous proteinases by α2M is considered to be irreversible (14, 45), residual activities toward high molecular weight (HMW) substrates and ligands have been reported for a number of complexes, including α2M/uPA (50). Previously, we demonstrated the presence of α2M/uPA complexes in edema fluids from patients with ARDS/acute lung injury (ALI) (36), observed the formation of similar complexes with exogenous urokinase ex vivo in rabbit PFs (35), and hypothesized that the endogenous activity of αM/uPA and their slow degradation could provide durable low-grade PA activity that might contribute to successful IPFT.

We previously reported that the levels of PAI-1-resistant αM/uPA complexes are increased in the PFs of rabbits with tetracycline (TCN)-induced pleural injury 24 h after scuPA-based IPFT (35). We also found that intrapleural scuPA generated durable intrapleural fibrinolytic activity in a rabbit model of EMP in which adhesions did not form because PF was drained via an indwelling chest tube (29). However, the mechanisms of intrapleural scuPA processing as well as the kinetics of formation of αM/uPA complexes and their contribution to the outcomes of pleural injury have not been evaluated. The focus of the present study is to understand the kinetics of intrapleural inactivation of scuPA and mechanisms of formation and breakdown of αM/uPA complexes in vivo in TCN-induced pleural injury. To achieve these objectives, we elucidated the time course of intrapleural scuPA activation to the mature enzyme, tcuPA; determined how tcuPA is inactivated and how αM/uPA complexes are formed; and finally assessed mechanisms by which the complexes may contribute to IPFT in the model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins and reagents.

The scuPA used in this study was a generous gift from Dr. Jack Henkin, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL. The tcuPA activity standard (100,000 IU/mg) was from American Diagnostica (Stanford, CT). Human plasma α2-macroglobulin (α2M), wt-human PAI-1, rabbit uPA, and rabbit wt-PAI-1 were purchased from Molecular Innovations (Novi, MI). Fluorogenic uPA substrate was purchased from Centerchem (Norwalk, CT). Fluorogenic plasmin substrate, plasminogen (PLG), and plasmin (PL) were from Haematologic Technologies (HTI, Essex Junction, VT). The protein concentrations were determined by use of a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). All in vitro and ex vivo experiments were carried out in a buffer, 0.05 M HEPES/NaOH (pH 7.4), with or without BSA (1 mg/ml) and/or NaCl (20 mM). The antibodies used included mouse monoclonal anti-human uPA (HUPA3G65, Molecular Innovations, Novi, MI) and goat anti-mouse, horseradish peroxidase conjugated (PAB0096, Abnova, Taiwan).

Animal model.

This work was done as a part of a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center, at Tyler. The TCN-induced pleural injury model was used as previously described (27). New Zealand White pathogen-free female rabbits that weighed 3.0 to 3.6 kg, from Charles River (Wilmington, MA), were used. At 48 h after intrapleural TCN injection, rabbits with pleural injury were treated with either scuPA or a vehicle control (sterile PBS) as previously reported (32). Pleural effusions were assessed by ultrasonography using Logiq e system (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). The scuPA or vehicle control was administered intrapleurally via a catheter (18 gage, 1.25 in. in length) and then cleared with 0.5 ml of PBS, after which 0.5-ml aliquots of PF were collected at 10, 20, 40, and 80 min after IPFT. PF cells were removed immediately by centrifugation as we previously reported (27, 28), and the citrated, cell-free samples were then stored at −80°C and analyzed. Anesthesia and postoperative pain medication were administered, as previously reported (32). During each preoperative and postoperative period, rabbits were carefully monitored for signs of overt pain or distress and to ensure animal stability. Euthesol (0.25 ml/kg), administered intravenously, followed by exsanguination of blood via renal aorta, was used for rabbit euthanasia.

Ultrasonography.

B-mode ultrasonography was performed using Logiq e system (GE Healthcare), equipped with R5.2.x software and a multifrequency transducer model 12L-RS (3–10.0 MHz) at a working frequency of 10 MHz. The chest wall hair of anesthetized rabbits was shaved with 851 IVAC vacuum clippers (Laube, Oxnard, CA). Ultrasound contact gel (Parker Laboratories, Fairfield, NJ) was used. The rabbits were held in a prone position and the right pleural space was scanned at the same midchest transverse and longitudinal planes in each animal.

Metrics of pleural injury.

Gross loculation injury scores (GLIS) were determined during necropsy and scored as reported previously (32). To document the level of injury independently of GLIS, pictures of rabbit hemithoraces were taken using a Nikon D300 camera (Nikkor 18–200 mm VR lens) after PFs were collected as described previously (32).

Human PFs.

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center in Tyler (UTHSCT) approved all studies that involved human PFs, which were deidentified. The PFs were collected at UTHSCT from patients with parapneumonic effusions, EMP, defined as previously reported (28). These fluids were obtained in a deidentified manner from the clinical laboratory and the clinical diagnosis was provided. Effusions were obtained from patients receiving antibiotic therapy for pleural infection and were either thoracentesis or postsurgical specimens. None of the patients received IPFT. None of the fluids from patients with EMP were frank pus and all were from patients with either gram stain- or culture-positive PFs. Malignant pleural effusions were also obtained from patients with cytologically proven pleural malignancy from patients with any form of solid neoplasia metastatic to the pleural compartment. Patients receiving chemotherapy were not excluded from analysis. None of the patients in this group received intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy. PF cells were removed by centrifugation as we previously reported (27, 28) and the citrated, cell-free samples were then stored at −80°C and analyzed.

uPA amidolytic activity assay.

Measurements of the amidolytic activity of uPA in human and rabbit PFs were carried out and analyzed as described (35).

PAI-1 activity assay.

Levels of active rabbit or human PAI-1 in the PFs were determined either by titrating the active inhibitor with solutions of uPA of a known concentration, as previously described (35), or using a commercially available ELISA (Molecular Innovations) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Measurements of active α2M in human PFs.

Active α2M was determined in human PFs as previously described (35, 36). Briefly, PFs were incubated with or without exogenous enzymes (tcuPA, 20–50 nM) for 0–18 h at 37°C in a volume of 100–200 μl of 50 mM HEPES/NaOH buffer with a pH of 7.4. Reaction mixtures were sampled, with aliquots withdrawn at 0, 2, 7, and 18 h, and their activities were measured. To estimate the activity of α2M/enzyme complexes, amidolytic activity was measured in the presence of an excess of PAI-1 (final concentration in the reaction mixture, 80–200 nM) (35, 36).

Immunoprecipitation of enzymes complexed with α2M.

PFs (10–20 ml) were incubated with exogenous uPA (20–100 nM) for 4–20 h at 37°C. At the end of incubation 80 μl of polyclonal sheep anti-human α2M antibodies (Meridian Life Science) were added and incubated on ice for 30 min, after which 40 μl of slurry of protein A agarose was added to the samples, which were then placed on a rocker for 4–6 h at 4°C. Resin was spun down and washed three times with 1 ml of cold HEPES buffer. Amidolytic uPA activity was measured in samples with and without the addition of an excess of PAI-1, as we previously reported (35).

PLG activation assay.

These analyses were performed as previously described (38).

Activation of PLG with α2M/uPA complexes.

α2M/uPA were prepared from human α2M (Molecular Innovations), which contained 0.3 mol of active α2M per mole of dimer, and tcuPA (Abbott) as previously described (36). PLG activation by α2M/uPA was performed as described (32, 34). Briefly, α2M/uPA (0–5 nM) was added to the mixture of Glu-PLG (100–250 nM) and fluorogenic PL substrate (SN-5) (0.1–0.2 mM) (HTI) in 0.05 M HEPES buffer pH 7.4 with 1 mg/ml BSA.

Incubation of endogenous and exogenous αM/uPA complexes with PFs.

To test whether proteolytic degradation of α2M/uPA complexes results in release of free uPA activity, rabbit PFs (50–100 μl) with or without supplementation with exogenous human α2M/uPA (20 nM) were incubated at 37°C for 0–26 h. Aliquots (5 μl) were withdrawn at 0, 16, and 26 h and their amidolytic activity with/without the addition of an excess of PAI-1 and PLG activating activity was measured as we previously reported (35, 36).

Western blot analysis.

α2M/uPA complexes formed in vivo and in vitro were subjected to nonreduced SDS-PAGE (4–12% gradient NuPage gel; Invitrogen), and analyzed via Western blot as described previously (35).

Data analysis and statistics.

Levels of statistical significance were determined by Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks and pairwise multiple comparison procedures (Holm-Sidak method and Tukey's test). Data analysis was performed using SigmaPlot, v11, as previously described (28).

RESULTS

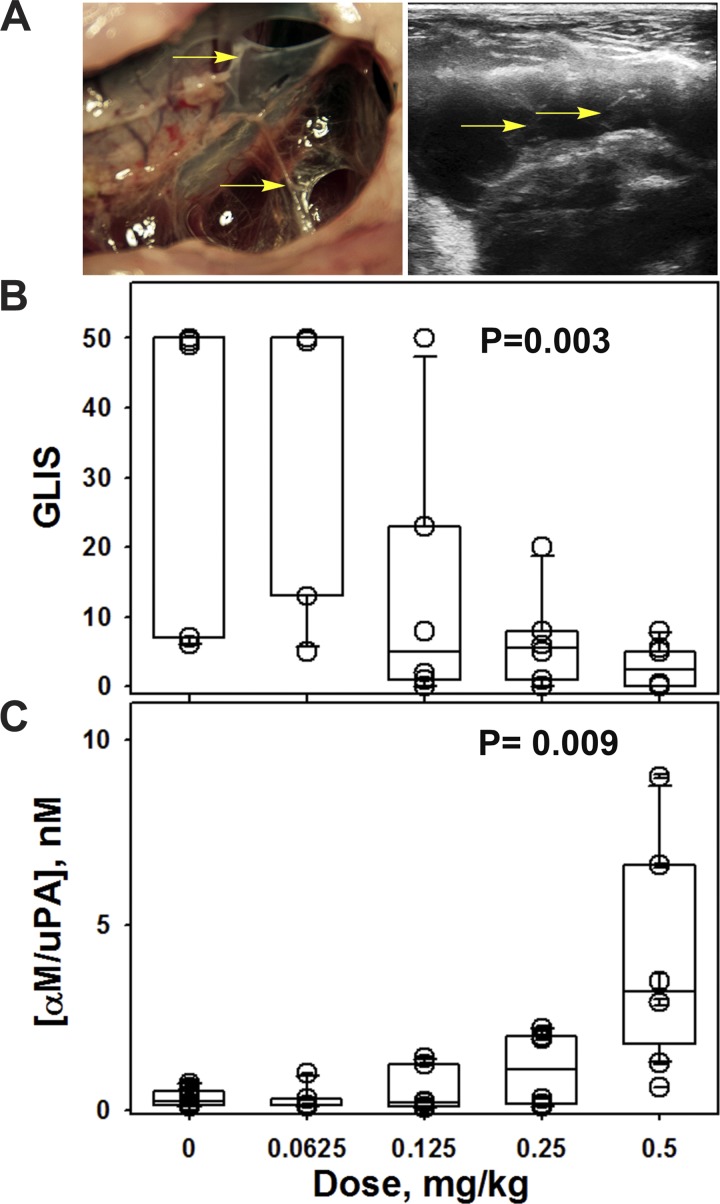

The level of intrapleural αM/uPA complexes 24 h after IPFT increases with increasing doses of scuPA IPFT. TCN-induced pleural injury in rabbits features extensive fibrin deposition (Fig. 1A, left) and massive pleural effusion (about 20–30 ml), which can be imaged via ultrasonography (Fig. 1A, right). Rabbits with TCN-induced pleural injury (Fig. 1A) were treated with a single intrapleural dose of 0.0625–0.5 mg/kg scuPA as described in materials and methods and euthanized at 24 h after IPFT, and the gross loculation injury score (GLIS; Fig. 1B) (32) and intrapleural concentration of αM/uPA complexes (35) were determined. The dosing range included doses of scuPA known to effectively (almost entirely) clear TCN-induced intrapleural adhesions (0.5 and 0.25 mg/kg), an intermediate dose that partially clears the adhesions (0.125 mg/kg), and a dose that is ineffective (0.0625 mg/kg). The box plots (Fig. 1) demonstrate that an increase in the dose of scuPA results in a decrease in the GLIS (Fig. 1B) and an increase in the intrapleural concentration of αM/uPA (Fig. 1C). Levels of uPA activity in sympathetic PFs from the uninjured (left) pleural space or in the circulation approximated the levels in the right (injured) PFs prior to intrapleural injection of scuPA (data not shown), indicating a low risk of leakage of uPA activity outside of the injured pleural space and consequent systemic PLG activation. Intrapleural scuPA generates PA activity that is well localized to the site of administration. There was almost no free uPA in the PFs, and the amount of uPA complexed with αM (the only enzymatically active species that possessed uPA activity) was significantly (three orders of magnitude, P < 0.05) less than the amount of fully activated scuPA in the dose that was used for IPFT. Next, we sought to evaluate the mechanisms of scuPA intrapleural processing to understand how scuPA generates durable PF PA activity and controls fibrinolysis up to 24 h after IPFT.

Fig. 1.

A trend toward improved outcomes due to escalating single-chain urokinase (scuPA) dose coincides with increased α-macroglobulin (αM)/urokinase (uPA) in pleural fluids 24 h after intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy (IPFT). A: macroscopic appearance of pleural injury in a rabbit 24 h after treatment with vehicle (left) with a gross loculation injury score (GLIS) of 50. Rabbits were subjected to ultrasonography (right) to assess pleural effusion accumulation and adhesion formation. Arrows indicate adhesions in the representative gross and ultrasonographic images. The GLIS was based on the fibrin strands, aggregates, and webs counted in the pleural space: too numerous to count, score 50; each discrete strand, 1; small aggregate (less than 5 mm), 2; larger aggregate or web, 5; clear pleural space, 0, as previously described (32). B: dependence of the efficacy of fibrinolytic therapy in the treatment of tetracycline (TCN)-induced pleural injury (GLIS) on the dose of scuPA. A box plot of the therapeutic outcome of the treatment of TCN-induced pleural injury in rabbits with different doses of scuPA [0 (n = 6), 0.0625 (n = 6); 0.125 (n = 6), 0.25 (n = 6) and 0.5 mg/kg (n = 6)]. There is a statistical difference (P < 0.05) between outcomes with the effective dose (0.5 mg/kg) and ineffective dose (0.0625 mg/kg). Animals were euthanized 24 h after intrapleural injection of scuPA (72 h after TCN-induced pleural injury) as described in materials and methods and previously (27). C: dependence of the intrapleural concentration of αM/uPA 24 h after IPFT on the dose of scuPA. Levels of intrapleural αM/uPA complexes in pleural fluids (PFs) of animals treated with different doses of scuPA as described in B were determined as previously described (35). Data in B and C are presented as box plots (showing interquartile ranges) with whiskers showing 5% and 95% values and P values representing results for Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA tests on ranks.

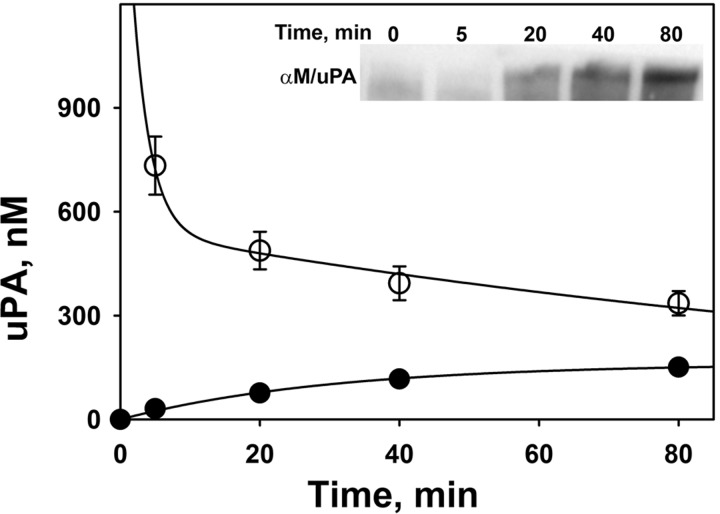

Two-step intrapleural uPA inactivation coincides with the formation of αM/uPA complexes. To evaluate the mechanisms of scuPA processing in vivo during IPFT in TCN-induced pleural injury, PFs were withdrawn at 0–80 min and were analyzed for uPA and PA activities. Changes of intrapleural concentrations of active uPA and αM/uPA complexes that occur after an intrapleural dose of scuPA that effectively clears pleural adhesions (0.5 mg/kg) in the model (30, 35) are shown in Fig. 2. The concentration of active uPA rapidly decreases following a two-step, α and β phase, exponential decay with t1/2α = 2.1 ± 0.3 and t1/2β = 62 ± 11 min, with amplitudes 70 and 30% of the initial uPA activity (assuming that all exogenous scuPA is equally distributed in 20 ml of PF and completely activated to tcuPA), respectively. Therefore, by 2 h after administration of scuPA IPFT, more than 90% of intrapleural uPA was inactivated. However, in each PF sample withdrawn αM/uPA progressively increased with time, contributing to the total uPA amidolytic activity (Fig. 2). Since αM/uPA is resistant to inhibition by PAI-1 but retains its activity toward LMW substrate (35, 36), uPA concentration in each aliquot of PF was determined from measurements of amidolytic activity immediately after treatment of the sample with a 5- to 20-fold molar excess of exogenous human recombinant PAI-1, as previously described (35, 36). At each time point shown in Fig. 2, total uPA activity is the sum of amidolytic activities of free uPA and uPA complexed with αM (Fig. 2). The concentration of αM/uPA approaches saturation at 60–80 min (Fig. 2). The increase in αM/uPA follows a single exponential process, [αM/uPA]t = [αM/uPA]max*{1−exp[−kobs*(time)]}; r2 = 0.967, where [αM/uPA]t, [αM/uPA]max, and kobs are molar concentrations of intrapleural αM/uPA at time t and at saturation and a pseudo-first-order rate constant for the αM/uPA formation, respectively. The values of [αM/uPA]max and kobs were 160 ± 30 nM and 0.021 ± 0.008 min−1, respectively (Fig. 2). Accumulation of αM/uPA in PF during IPFT with scuPA over time was also visualized by Western blot (Fig. 2; inset). Increased intensity of the αM/uPA band occurred with time and approached saturation at ∼60–80 min. Therefore, within 2 h after scuPA IPFT, the intrapleural concentration of αM/uPA increases by more than three orders of magnitude compared with the endogenous concentration of αM/uPA prior to IPFT and becomes a major reservoir of active uPA (Fig. 2). These results support the hypothesis that αM/uPA, which at 80 min after IPFT accounts for 8–12% of initial uPA activity, could contribute to the intrapleural activation of PLG for the next 22 h. Since total uPA activity decreased progressively (Fig. 2), activation of the majority of intrapleural scuPA at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg to mature tcuPA likely occurred rapidly in PF, within the first 10 min after beginning IPFT. To decipher the mechanisms of early intrapleural processing of scuPA and αM/uPA in vivo, the kinetics of uPA and PLG-activating activities were next analyzed by using a range of doses of scuPA IPFT.

Fig. 2.

In vivo kinetics of uPA inactivation and αM/uPA complex formation during scuPA treatment in TCN-induced pleural injury in rabbits. Changes in the concentration of total active uPA (○) and uPA complexed with αM (●) in PF with time. scuPA (0.5 mg/kg) was injected into the pleural space with TCN-induced pleural injury. The figure illustrates findings from 1 animal (3 independent repeats), which are representative of those identified in 6 rabbits independently subjected to the same analyses. PF was withdrawn at the indicated time points, immediately frozen on dry ice, and analyzed for total uPA amidolytic activity and uPA activity resistant to an excess of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1, which represents αM/uPA complexes). The initial uPA activity was estimated by assuming equal distribution of scuPA in 20 ml of PF and its complete activation to 2-chain uPA (tcuPA). Total uPA concentration activity at each point is the sum of concentrations of free uPA (not shown) and αM/uPA. The solid line represent the best fits of a 2-exponential equation: [uPA] (nM) = a*exp[−b*(time)]+c*exp[−d*(time)]; r2 = 0.997. The values of coefficients for the best fit are a = 1,450 ± 50 and c = 550 ± 40 nM, b = 0.33 ± 0.04, and d = 0.011 ± 0.005 min−1 (t1/2 for fast and slow phases of free uPA inactivation are 2.1 and 62 min). A single exponential equation, [αM/uPA]t = [αM/uPA]max*{1−exp[−kapp*(time)]}, was fit to the data αM/uPA (solid symbols; r2 = 0.967), where kapp, [αM/uPA]t, and [αM/uPA]max are the apparent first order rate constant of αM/uPA formation and the concentrations of αM/uPA at time t and at saturation, respectively; [αM/uPA]max = 160 ± 30 nM; and kapp = 0.021 ± 0.008 min−1. Inset: a representative Western blot (n = 4 independent experiments) depicting the formation of αM/uPA complexes in vivo at 0–80 min, visualized by Western blot analysis of PF samples resolved on SDS-PAGE. The blot was probed with mouse anti-human uPA antibody and shows bands corresponding to the αM/uPA complex with a relative electrophoretic mobility of 240–280 kDa.

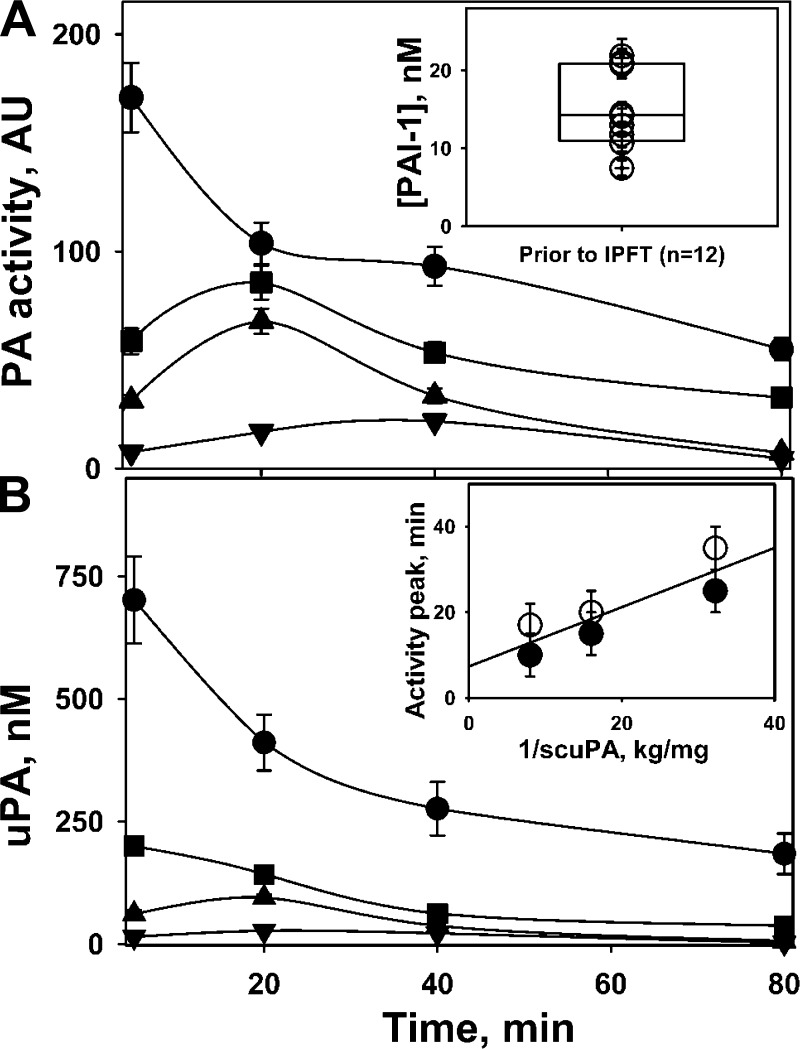

Endogenous active PAI-1 affects the rate of intrapleural activation of scuPA. Elevated endogenous active PAI-1 (Fig. 3A; inset), which is a “molecular signature” of TCN-induced pleural injury in rabbits (32), was determined in the samples of PF withdrawn just prior to IPFT. The values of PAI-1 activity (median = 14.2 nM, n = 12) varied in the same relatively narrow range (10–20 nM) previously observed for this model (32). Equilibrium between active and inactive species of the proenzyme scuPA favors the latter (35), and low kon = 0.072 min−1 limits the rate of inactivation of scuPA by PAI-1. Although the interaction of endogenous active PAI-1 with active species of scuPA and tcuPA is diffusion limited (kass > 106 M−1·s−1), if [active PAI-1] > ([active scuPA]+ [tcuPA]), the reaction becomes limited by kon (35). Indeed, a decrease in scuPA dose (0.125 mg/kg and below) dramatically changed the profile of both PA (Fig. 3A) and amidolytic (Fig. 3B) uPA activities in samples of PF. The peak of uPA activity (Fig. 3) reflected a delay in intrapleural activation of prourokinase to tcuPA in the presence of active PAI-1. As expected, the peak of uPA activity occurred later with a decrease in scuPA dose (Fig. 3). The time of the peak for both total PA and amidolytic activity of uncomplexed uPA reciprocally depended on the dose of scuPA (Fig. 3B, inset). Endogenous PAI-1, which rapidly inhibits both the active form of scuPA and tcuPA (35), delays the intrapleural activation of scuPA and, likely, endogenous PLG due to the decrease of PA activity (Fig. 3). Therefore, levels of both PA and fibrinolytic activity remain low, until all endogenous intrapleural PAI-1 is neutralized completely. Since the equilibrium concentration of the active species of scuPA increases with an increase in the dose of the fibrinolysin, the peak of uPA amidolytic and PA activities shifts quickly from 35–40 to less than 5 min when the dose of scuPA increases from 0.0313 mg/kg (where equilibrium concentration of active scuPA is less than that for endogenous active PAI-1) to 0.5 mg/kg (where the concentrations of active scuPA and PAI-1 are comparable) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Rate of intrapleural activation of scuPA to the mature enzyme tcuPA slows with a decreasing doses of scuPA IPFT. Changes in intrapleural plasminogen (PLG)-activating (PA) (A) and free uPA amidolytic (B) activities in the PFs of rabbits with TCN-induced injury are shown over time. A dose of scuPA [0.5 (●), 0.125 (■), 0.0625 (▲), and 0.0313 (▼) mg/kg] was administered intrapleurally to rabbits (n = 4 animals studied, 1/dose) with TCN-induced pleural injury, and PA (A) and amidolytic free uPA (B) activities were measured in aliquots (5–80 min) as described in materials and methods. The figure illustrates findings from 1 animal (3 independent repeats), which are representative of those identified in 6 rabbits independently subjected to the same analyses. The concentration of active PAI-1 in PF (A, inset), withdrawn prior to IPFT was determined as previously described (32). B, inset: the peak of both PA (open symbols) and amidolytic uPA (solid symbols) activities depended reciprocally on the dose of scuPA IPFT (range 0.0313–0.125 mg/kg).

Although the initial PA and uPA activities at the effective doses of scuPA are higher than those for ineffective doses (Fig. 3), intrapleural fibrinolytic activity is limited by the level of endogenous PLG, which is fully converted to PL between 0 and 80 min for both effective (0.5 mg/kg) and ineffective (0.0625 mg/kg) doses of scuPA IPFT (Fig. 3A). PF PGN is exhausted through 80 min after administration of all doses of scuPA but activatable PGN is restored within PFs by 24 h after scuPA IPFT. Elevated intrapleural PA activity, indicating activation of endogenous PLG to PL, is detected over 80 min at every dose of scuPA (Fig. 3A). However, only treatment using a dose of 0.5 mg/kg most effectively clears TCN-induced pleural adhesions (Fig. 1B). By contrast, 0.0625 mg/kg of scuPA is ineffective (Fig. 1B) despite full activation of the detectable endogenous PLG at 0–80 min (Fig. 3A). These observations suggest that fibrinolysis after 80 min of scuPA administration may play a significant role in clearance of intrapleural adhesions observed at 24 h (Fig. 1B).

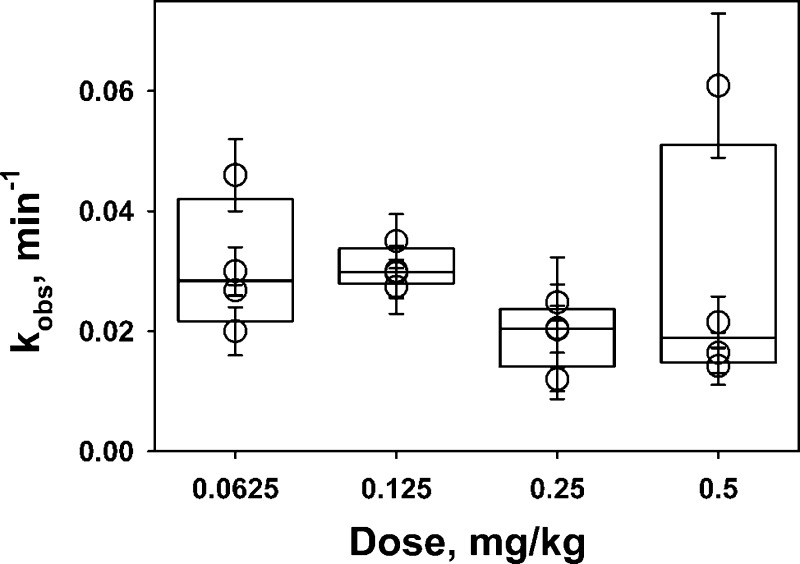

The rate of intrapleural slow-phase inactivation of uPA does not depend on the dose of scuPA. PF uPA activity generated by scuPA IPFT is rapidly inactivated (Figs. 2 and 3) even though the intrapleurally administered scuPA exceeds the sum of endogenous active PAI-1 (10–20 nM) and αM (150–250 nM). The fast α-phase occurs in the first 5–10 min (Fig. 2), where up to 60–70% of initial uPA activity is lost. PF withdrawn at 5–80 min allowed for evaluation of free uPA inactivation during the second, slower β-phase (10–80 min). The observed first order rate constants (kobs) of loss of free uPA activity were determined from amidolytic uPA, sensitive to inhibition by PAI-1, in PF withdrawn during IPFT with different doses of scuPA. A single exponential equation was fit to the dependences of concentration of active free uPA ([free uPA] = [total uPA] − [αM/uPA]) on time. The values of kobs (kobs = 0.018 ± 0.005 min−1, Fig. 4) were independent of the dose (initial intrapleural concentration) of scuPA IPFT, indicating that the rate of slow-phase inactivation of uPA activity generated by different doses of scuPA IPFT is comparable and independent of the intrapleural concentration of uPA. Therefore, in addition to the fast inactivation of tcuPA and the active species of scuPA by PAI-1, there is a PAI-1-independent mechanism that targets intrapleural uPA activity, which results in a fast decrement of intrapleural concentrations of free uPA.

Fig. 4.

The rate of the slower phase of intrapleural inactivation of free uPA is independent of the dose of scuPA used for IPFT. The observed first order rate constants (kobs) for inactivation of free uPA were determined from measurements of amidolytic uPA activity. Amidolytic activity in samples of PF (n = 6 for each dose of scuPA used) withdrawn at 5–80 min after IPFT was measured with and without an excess of exogenous human recombinant PAI-1, which represent αM/uPA and total uPA activity, respectively. A single exponential equation was fit to the dependences of concentration of active free uPA, [free uPA] = [total uPA] − [αM/uPA], on time. The values of kobs were plotted against the dose (0.0625–0.50 mg/kg) of scuPA IPFT. There is no statistical difference (P > 0.05) between values of kobs between any 2 doses of scuPA.

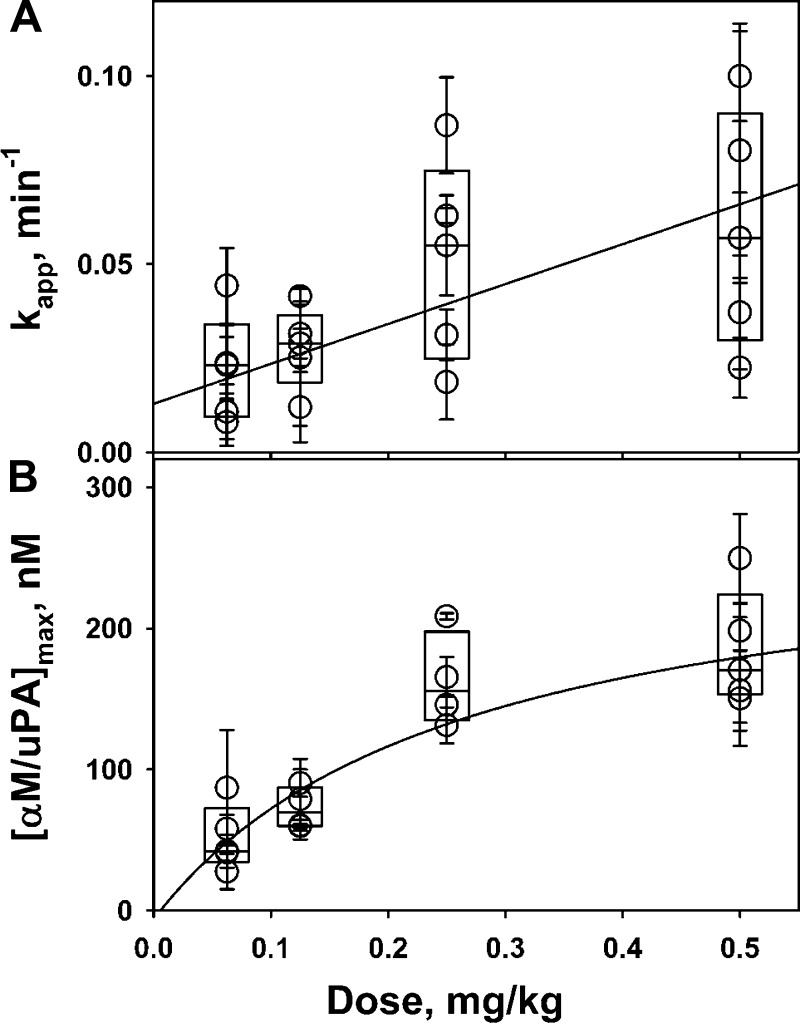

The maximal intrapleural concentration of αM/uPA increases with an increase in the dose of scuPA. Levels of intrapleural αM/uPA with time (0–80 min after IPFT) were determined for different doses of scuPA, and apparent first order rate constants of formation of αM/uPA (kapp) were estimated by fitting a single exponential equation to the data as described in Fig. 2 and the materials and methods. The values of kapp were plotted against an initial concentration of scuPA (assuming that the whole dose of fibrinolysin was diluted in 20 ml of PF; Fig. 5A), and results were fit with a linear equation to the plot of medians of kapp for each dose to estimate the second order association rate for in vivo formation of αM/uPA complexes (kass = 580 ± 60 M−1·s−1). Moreover the amount of intrapleural αM/uPA at saturation ([αM/uPA]max) increased with increasing scuPA dose (Fig. 5B) and approached the maximum 260 ± 70 nM, which likely reflects the maximal intrapleural concentration of the endogenous active αM.

Fig. 5.

Kinetics of intrapleural formation of αM/uPA complexes. Dependences of (A) the apparent first order rate constant (kapp) of αM/uPA formation and (B) maximal intrapleural concentration of αM/uPA ([αM/uPA]max) on the dose of scuPA IPFT. Amidolytic uPA activity in aliquots of PF (diluted 1:20) withdrawn at 5–80 min after intrapleural injection of scuPA (0.0625–0.5 mg/kg, n = 6 for each dose of scuPA used) was measured in the presence of 100–150 nM of exogenous active human recombinant PAI-1 as previously described (35, 36). A single exponential equation, [αM/uPA]t = [αM/uPA]max*{1−exp[−kapp*(time)]}, was fit to the data (solid symbols, Fig. 2), where kapp, [αM/uPA]t, and [αM/uPA]max are the apparent first order rate constant of αM/uPA formation and the concentrations of αM/uPA at time t and at saturation, respectively. The values of kapp (A) and [αM/uPA]t (B) were plotted against scuPA dose. The second order association rate constant (kass) for intrapleural formation of αM/uPA (kass = 580 ± 60 M−1·s−1) was estimated from the slope of the best fit of a linear equation to the plot of medians of kapp on the dose of scuPA (A, solid line), assuming that the initial concentration of scuPA equals to immediate distribution of the fibrinolysin in 20 ml of PF. A hyperbolic equation was fit to the dependence of medians of [αM/uPA]max on the dose of scuPA (B, solid line) to estimate a saturation level of [αM/uPA]max that reflects the intrapleural concentration of active αM in the PF.

High levels of active uPA complexed with αM, observed at 80 min after IPFT (Fig. 5B), were decreased by two orders of magnitude by 24 h after IPFT (Fig. 1C). A correlation between the level of αM/uPA and the dose was detectable over 24 h after administration of intrapleural scuPA, indicating intrapleural half-life time for these complexes of 3.0–3.5 h (assuming single exponential inactivation). These results demonstrate that αM/uPA becomes a major reservoir of intrapleural active uPA between 2 and 24 h after IPFT of TCN-induced pleural injury in rabbits.

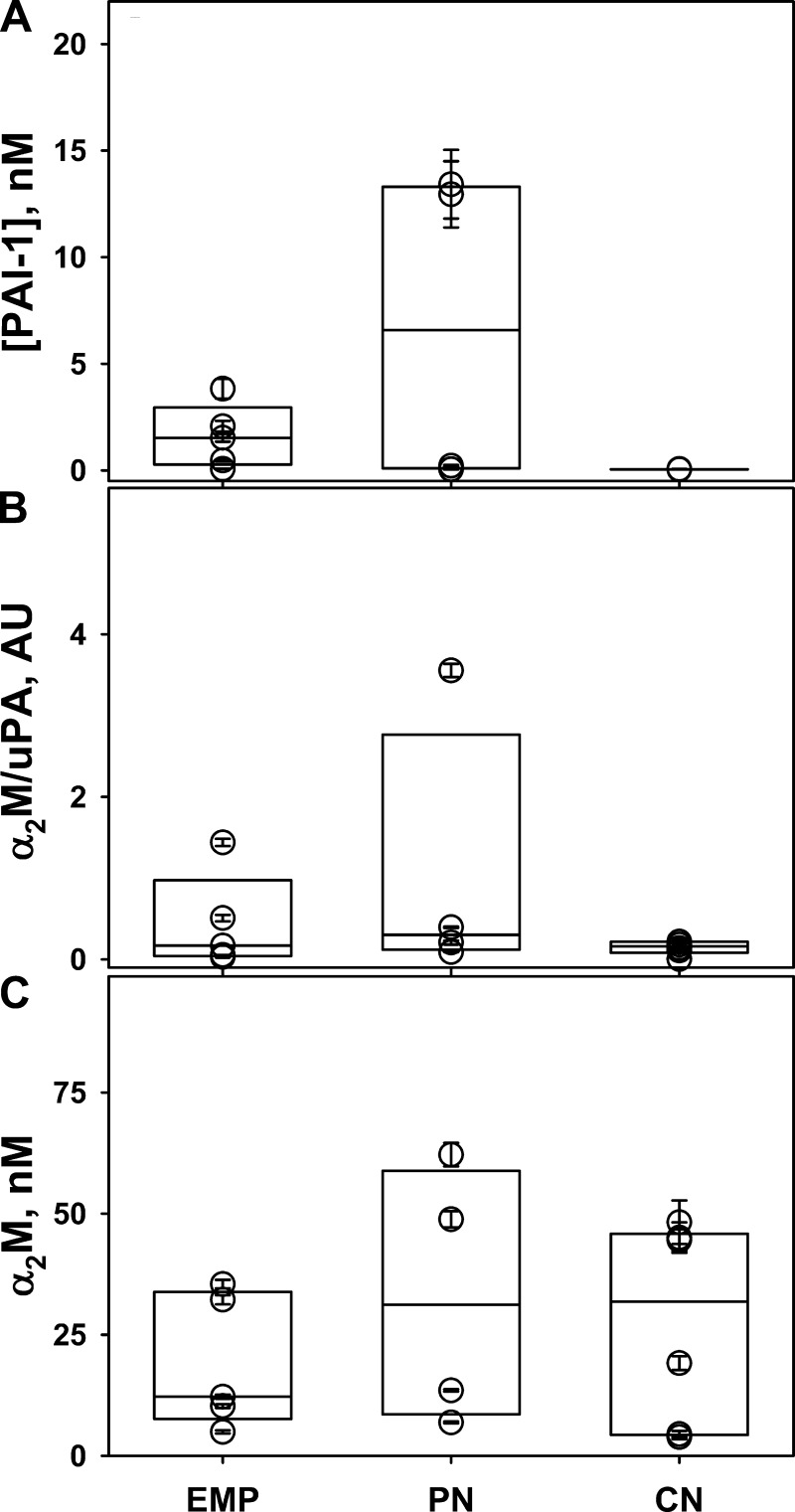

Human PFs contain active PAI-1, endogenous α2M/uPA, and high levels of active α2M. To determine whether similar mechanisms of uPA processing are operative in human PFs, those from patients with EMP, pneumonia parapneumonic (PN), and malignant (CN) pleural effusions were analyzed for the presence of endogenous active PAI-1, uPA activity resistant to PAI-1, and active α2M (Fig. 6). Endogenous active PAI-1 was elevated (up to 12 nM in PN samples) in the EMP and PN PFs analyzed (Fig. 6A). Elevated levels of PAI-1 activity were previously reported in human EMP PFs (2) and in the TCN-injured rabbit pleural space Fig. 3A; inset; (32). Moreover, similar to edema fluids from patients with ALI/ARDS (36), all three groups of infectious (PN and EMP) and noninfectious (CN) PFs contained uPA amidolytic activity that was resistant to inactivation by exogenous PAI-1 (Fig. 6B). Finally, a significant fraction of amidolytic activity of the exogenous uPA added to these PFs became protected from inhibition by PAI-1 after incubation at 37°C for 4–10 h (Fig. 5C), indicating the formation of molecular cage-type complexes between uPA and endogenous active α2M. As expected from the data previously obtained in rabbit PFs (35), anti-α2M antibodies coprecipitate uPA amidolytic activity that is resistant to PAI-1 (not shown), directly confirming that there is formation of α2M/uPA complexes in human PFs from endogenous active α2M and exogenous uPA. Assuming that the levels of α2M/uPA reflect saturation and suggesting stoichiometry one uPA molecule per α2M dimer, intrapleural concentration of active α2M in humans could approach 20–100 nM (Fig. 6C). Therefore, both rabbit and human PFs contain high levels of active endogenous α-macroglobulins, which, under conditions of IPFT, are able to form complexes with exogenous uPA and protect exogenous scuPA from fast inactivation with PAI-1, significantly increasing the half-life of uPA activity in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Human PFs contain endogenous active PAI-1, α2M/uPA complexes, and high levels of active α2M. A: levels of active PAI-1 in human PFs. PFs from patients with empyema (EMP, n = 5), parapneumonic pleural effusions associated with pneumonia (PN, n = 4), and malignant pleural effusions (CN, n = 6) were subjected to ELISA specific to active human PAI-1 (Molecular Innovations). Elevated levels of active PAI-1 detected in PFs of patients with EMP and PN. B: endogenous α2M/uPA activity in PFs of different etiology. Amidolytic uPA activity in the PFs from patients with EMP, PN, and CN (n = 5, 4, and 6, respectively) was measured in the presence of 50 nM exogenous active human PAI-1 by using a fluorogenic substrate, as previously described (35, 36). Endogenous uPA activity resistant to inhibition with PAI-1 reflects the level of intrapleural α2M/uPA complexes. C: incubating PFs with an excess of exogenous uPA results in the formation of “molecular cage”-type complexes with endogenous active α2M. PFs from patients with EMP, PN, and CN (n = 5, 4, and 6, respectively) were incubated with 100 nM uPA for 10 h at 37°C, and uPA amidolytic activity was measured in the presence of 400 nM exogenous active human PAI-1. The level of α2M/uPA formed (uPA activity resistant to inactivation with PAI-1) reflects the level of endogenous active α2M in human PFs. The data are presented in a box plot format as described in the legend to Fig. 1. There is no statistical difference (P > 0.05) between concentrations of endogenous active α2M between any of the groups of PFs.

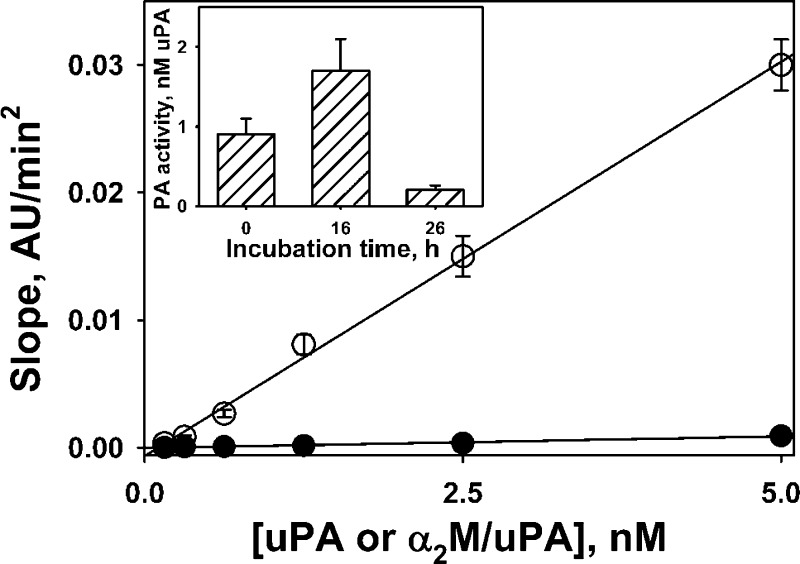

Endogenous activity of αM/uPA and products of its degradation contribute to intrapleural PA activity. The protracted bioavailability of intrapleural scuPA in the form of α2M/uPA complexes suggests that two alternate mechanisms of activation of endogenous PLG could be operative: 1) endogenous PA activity of αM/uPA, and 2) uPA generated due to intrapleural degradation of αM/uPA. To test the first mechanism, human α2M/uPA complexes with a stoichiometry 1.0 or 0.3 mol of uPA per mole of active tetramer of α2M were obtained and characterized as previously described (35, 36). The PA activity of α2M/uPA complexes was compared with that of tcuPA (Fig. 7), as previously described (34). As expected (50), the rate of PLG activation by α2M/uPA was almost two orders of magnitude lower than that of tcuPA (Fig. 7). To test whether intrapleural degradation of αM/uPA could contribute to the PA activity, samples of PFs, withdrawn at 80 min from pleural cavities of rabbits treated with scuPA (0.5 mg/kg), were incubated at 37°C. The PA activity in the samples (n = 2) increased after 16 h and then decreased after an additional 10 h of incubation (Fig. 7; inset). Finally, similar results were observed after incubation of the same PFs supplemented with 20 nM exogenous human α2M/uPA complexes at 37°C (data not shown). Therefore, active uPA entrapped in the complexes with αM and protected from interaction with HMW substrates (PLG) and inhibitors (PAI-1) is slowly released as a result of intrapleural degradation of αM/uPA (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 7.

αM/uPA complexes possess intrinsic PA activity, and free uPA resulting from their degradation contributes to durable PA activity in IPFT with scuPA. Rates of plasmin generation due to activation of 100 nM human Glu-PLG by tcuPA (○) and α2M/uPA (●) were measured in the presence of fluorogenic plasmin substrate as previously described (32, 34). Slopes of linear dependences of an increase in the fluorescence emission at 470 nm (excitation 352 nm) vs. time in minutes squared were plotted against the concentration of tcuPA or α2M/uPA. Solid lines represent the best (R2 > 0.98) fit of a linear equation to the data. The relative PA activities of α2M/uPA (2.9% of tcuPA) were calculated as a ratio of slopes for tcuPA (6.2 × 10−3 AU·min2) and α2M/uPA (0.18 × 10−3 AU·min2). Inset: changes in PA activity in the PFs of rabbits treated with scuPA (0.5 mg/kg) during incubation at 37°C. Samples of rabbit PFs (withdrawn 80 min after scuPA IPFT) were incubated for 0, 16, and 26 h at 37°C. PA activity in the samples was measured (32, 34) and expressed as a concentration of free uPA. An increase in PA activity reflects the formation of free uPA (specific PA activity 30–50 times higher than that of α2M/uPA). Similar results (not shown) were obtained with PFs supplemented with exogenous α2M/uPA (20 nM).

Fig. 8.

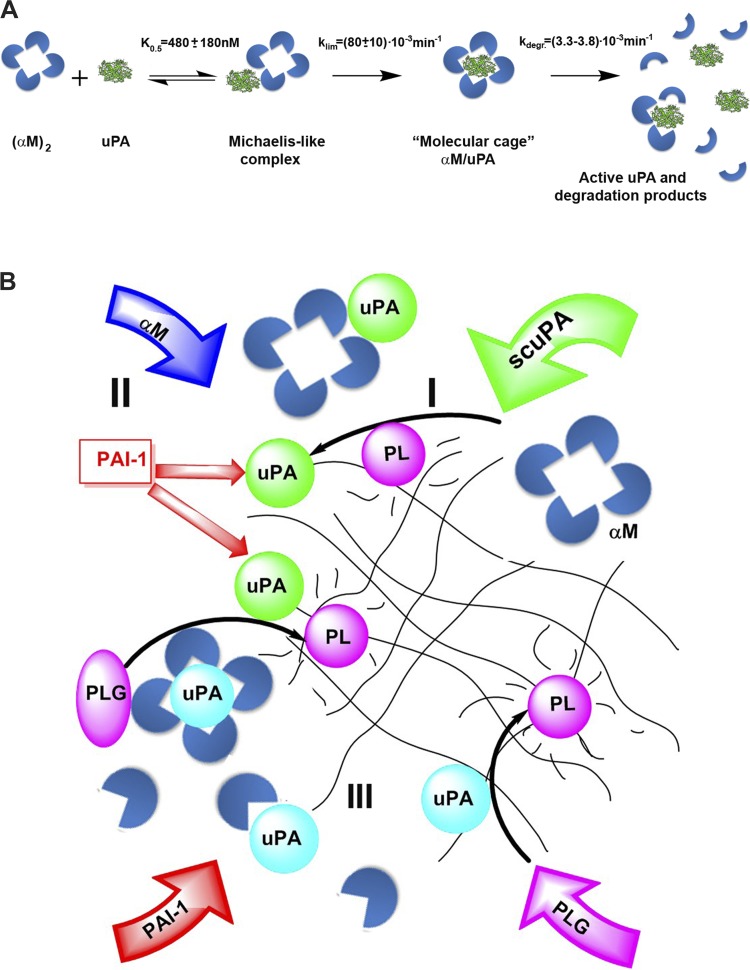

Formation of intrapleural αM/uPA (A) and processing of scuPA (B) during IPFT of TCN-induced pleural injury in rabbits. A: mechanism of intrapleural formation and degradation of αM/uPA complexes. Fast formation of a reversible Michaelis-like intermediate complex (K0.5 = 480 ± 180 nM) from an active, endogenous dimer (αM)2 (intrapleural concentration 260 ± 70 nM) and uPA (0.2–2.0 μM), results in molecular cage-type αM/uPA complexes (klim = 0.08 ± 0.01 min−1). The endogenous activity of relatively stable (t1/2 = 3.0–3.5 h) αM/uPA provides low levels of intrapleural PA activity. Slow degradation and inactivation of αM/uPA produces transient free uPA, which neutralizes PAI-1 and activates PLG. B: the mechanism of intrapleural processing of scuPA injected (green arrow) during IPFT for rabbits with TCN-induced injury includes 3 major steps: 1) activation of scuPA to mature 2-chain enzyme (green circles), which is delayed by endogenous active PAI-1 (straight red arrows); 2) fast inactivation of free uPA with simultaneous formation of up to 260 ± 70 nM of αM/uPA, which possess low-grade PA activity; and 3) slow degradation of intrapleural αM/uPA, which generates active free uPA (blue circles). A supply of active αM from the circulation is shown as a blue arrow, and overexpression of PAI-1 and de novo-synthesized PLG with red and purple arrows, respectively. Activation of endogenous PLG to plasmin (PL) (purple ovals and circles, respectively) by uPA and scuPA by PL is indicated by black arrows. Durable intrapleural PA activity (when a sum of free residual uPA, uPA formed due to degradation of αM/uPA, and endogenous uPA and tPA is higher than the level of active PAI-1) results in longer activation of de novo-synthesized PLG and exposure of fibrin deposits (black net) to increased amounts of PL over longer periods of time.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides the first comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms of early (0–80 min) processing of intrapleural scuPA (illustrated in Fig. 8), which effectively clears pleural adhesions in rabbits with TCN-induced pleural injury (27, 30, 32). This mechanism (Fig. 8B) includes three major steps: 1) activation of prourokinase, which is delayed by endogenous active PAI-1; 2) fast inactivation of free uPA (60–70% free uPA inactivation in the α phase with t1/2α = 2–3 min and 30–40% in the relatively slower β phase, t1/2β = 40 ± 10 min) with simultaneous formation of up to 260 ± 70 nM of αM/uPA, which possesses low-grade PA activity (Fig. 7); and 3) slow degradation (Fig. 8; t1/2 = 3.0–3.5 h) of intrapleural αM/uPA, which generates active free uPA (Figs. 7 and 8A).

The proposed mechanism of scuPA processing during IPFT is shown in Fig. 8B. αM/uPA represents the major reservoir of active uPA by 80 min after scuPA IPFT (up to 10% of the initially administered scuPA). uPA activity that is generated as a result of the slow degradation of αM/uPA complexes (Fig. 8B, blue circles) contributes to the total intrapleural PA activity, together with endogenous uPA and tPA, as well as residual free uPA (Fig. 8B, green circles). Endogenous PLG activation and extended exposure of intrapleural fibrin (represented by net; Fig. 8) to accumulating endogenous PL contributes to a favorable outcome. If the total PA activity exceeds the level of active PAI-1 (red arrow), the activation of endogenous PLG (purple arrow) within PFs results in durable fibrinolytic activity and adhesion clearance. Replenished PLG (purple arrow) in PF is likely supplied over time by extravasation from the inflamed, hyperpermeable pleural vasculation. At both effective and ineffective scuPA IPFT doses (Fig. 1B), the majority of available endogenous PF PLG is activated over 80 min because of elevated intrapleural PA activity (Fig. 3A). Thus durable PA activity generated after 80 min may contribute to effective clearance of pleural adhesions in the model. αM/uPA complexes release free uPA at 80 min to 24 h (Fig. 7, inset, Fig. 8) and, thus, may contribute to maintaining total intrapleural PA activity above the level of active PAI-1. At an effective dose of scuPA IPFT (0.5 mg/kg), this protracted reservoir of PA activity likely contributes to extended activation of PLG, generating sufficient amounts of PL to clear adhesions in this model. As soon as the total intrapleural PA activity becomes quenched by endogenous active PAI-1 (usually by 24 h after IPFT; data not shown), the level of endogenous PLG increases.

Prourokinase possesses low endogenous enzymatic activity, owing to the equilibrium between active and inactive species, and reacts with PAI-1 with the rate limited by slow transition from the inactive to the active form (35). The rate of intrapleural neutralization of endogenous active PAI-1 (10–20 nM; Fig. 3) by scuPA depends on the dose of the fibrinolysin [initial concentration of the active scuPA species (35)]. As a result, the peak of uPA activity during IPFT is shifted to a later time with lower doses of scuPA (Fig. 3). Since scuPA can generate complexes with endogenous αM under conditions of overexpression of PAI-1 in vitro (35) and in vivo (36), the mechanism of formation of αM/uPA molecular cages (Fig. 8A) likely includes a reversible Michaelis-like complex, in which an enzyme/proenzyme is protected from interaction with PAI-1 (35, 36). The kinetics of αM/uPA formation in vivo (Fig. 5A) supports such a bimolecular mechanism with a Michaelis-like intermediate complex (Fig. 8). Indeed, fitting a hyperbolic equation (not shown) to a dependence of medians of kapp on the dose of scuPA (Fig. 5A) results in klim = 0.08 ± 0.01 min−1 and K0.5 = 480 ± 180 nM (based on ultrasonography measurements, an average initial volume of PF is ∼20 ml).

The intrapleural concentration of αM/uPA increases with an increase in the dose of scuPA (from ineffective 0.0625 mg/kg to effective >0.25 mg/kg). On the other hand, the maximal level of αM/uPA is limited by the intrapleural concentration of endogenous active αM, which may differ from animal to animal (Fig. 5B). Since αM/uPA reaches saturation at 260 ± 70 nM (Fig. 5B), the concentration of intrapleural active αM could be as high as 500 nM, assuming a stoichiometry of one molecule of uPA per dimer of αM (Fig. 8). Although α2M is the major macroglobulin in humans, with levels in the circulation approaching 1–2 mg/ml (6), rabbits also synthesize α1M as an acute-phase protein (19). Both rabbit αMs (type 1 and 2) can interact with uPA (4, 35, 52). Since αMs are not synthesized within the pleural compartment, a significant fraction of active αM (and, possibly, PLG) in the injured pleural space of both rabbits and humans likely originates from the circulation. αM synthesis, its liver degradation, and binding to other proteins could therefore influence its concentration in PFs. Although the pharmacokinetics of αM may also be altered by confounding factors, our data show that active αMs in the PFs of rabbits and humans with exudative pleural effusions can form readily detectable bioactive complexes with uPA.

Notably, the concentration of active intrapleural αM observed in rabbits is close to the value of K0.5 estimated from data shown in Fig. 5A. Therefore, even when low doses of scuPA IPFT are administered, a significant fraction of uPA [up to half of the fibrinolysin (Fig. 8A)] could form a Michaelis-like complex with endogenous active αM. Reversible binding of scuPA to αM can also contribute to the delay in scuPA activation that was observed at low doses (Fig. 3). Moreover, the proposed mechanism (Fig. 8A) explains the formation of molecular cages with prourokinase observed in edema fluids of patients with ARDS/ALI (36).

The saturation of intrapleural αM/uPA at 60–80 min after IPFT of TCN-induced pleural injury in rabbits occurs when 90% or more of free uPA is inactivated (Fig. 2, 4), confirming that αM/uPA is a significant reservoir of durable PA activity at 1.5–24 h after scuPA IPFT. Thus αM/uPA complexes, which possess endogenous PA activity at the level of several percent of tcuPA (Fig. 7; Ref. 50), when present in a high concentration in vivo, may contribute to durable low-grade intrapleural PA activity, which activates endogenous PLG and supports fibrinolysis, as we previously suggested in ex vivo studies (35). Significant (up to 5–8 nM) level of αM/uPA detected 24 h after IPFT indicates that αM/uPA complexes could have a half-life of 3.0–3.5 h in the pleural space. Degradation of αM/uPA in the pleural space (Fig. 8) provides additional free active enzyme (Fig. 7), also contributing to the total PA activity that supports protracted fibrinolysis and successful IPFT.

Serine proteinases in the bloodstream interact quickly with primary, specific inhibitors (serpins), slowly with secondary, nonspecific ones (αMs), and are subject to rapid clearance through LRP receptor-mediated uptake and the liver (16, 39). In contrast, an injured pleural space is a rather unique and sequestered compartment, which contains loculated exudative fluid with levels of PAI-1 that are markedly increased compared with plasma (25, 41). The mechanism of intrapleural processing of prourokinase is associated with a significant increase in the half-life of activity of free uPA for the slower phase (t1/2β = 40 ± 10 min), compared with tcuPA in the rabbit circulation [t1/2β = 6 min (10)]. Although most of the fast α-phase of tcuPA inactivation (estimated t1/2α = 2–3 min) occurred prior to the withdrawal of the first aliquot of PF, the results (Figs. 2 and 3) indicate that the majority of intrapleural scuPA in the effective dose is activated to tcuPA in first 5–10 min. Nevertheless, delayed activation of scuPA to tcuPA (Fig. 3), slow inactivation of tcuPA (Fig. 4), and slow degradation of αM/uPA (Fig. 8) are potential advantages for intrapleural use.

Rabbit and human PFs demonstrated strikingly similar properties with respect to the processing of scuPA, levels of endogenous PAI-1 and uPA activity resistant to PAI-1, as well as amounts of α2M/uPA complexes formed in human PFs treated with exogenous uPA. These complexes were comparable to those found previously in lung edema fluids from humans with ARDS/ALI (36). Decreased levels of active PAI-1 and α2M in human PFs, relative to levels of both molecules in PFs of rabbits with TCN-induced pleural injury, could result from the limitations of the collection and processing of human PFs. Since both active PAI-1 and α2M are prone to spontaneous inactivation and degradation, samples of PF from rabbits were immediately snap-frozen on dry ice and kept at −80°C. Processing and storing PFs collected from patients typically takes longer, with potential spontaneous inactivation of endogenous PAI-1 and α2M. Although the accessibility of the active site for HMW inhibitors and substrates is typically restricted because of steric hindrance of the molecular cage, fibrinogen degradation by endogenous α2M/proteinase complexes was first reported almost 40 years ago (22). Moreover, the α2M/uPA possess up to 1–2% intrinsic uPA PLG activating activity (Fig. 7; Ref. 50). A statistically significant correlation between levels of α2M and d-dimers, observed in pleural effusions after trauma (46), likewise suggests that endogenous α2M complexes could contribute to homeostatic mechanisms of intrapleural fibrinolysis in humans. Successful IPFT with uPA has been reported in children (49), which agrees with reports of elevated concentrations of α2M in children (17). These findings support the concept that scuPA IPFT could result in a durable, low-level PA activity that may confer a safety advantage. Thus scuPA's unique mechanism of intrapleural processing (Fig. 8B) provides low-grade PA activity for up to 24 h after IPFT with a single dose of the fibrinolysin, which may likewise help clear pleural adhesions progressively.

In summary, we show that the ability of intrapleural scuPA to resist PAI-1 is attributable to relatively slow activation and early formation of αM/uPA, contributing to the bioavailability of the fibrinolysin. αM/uPA complexes, which possess intrinsic PA activity (50), are degraded in the pleural space, forming free uPA that contributes to the neutralization of endogenous PAI-1 and to the total PF PA activity. Although the focus of the present work is elucidation of the early (0–80 min) processing of intrapleural scuPA and mechanisms of formation of αM/uPA, a limitation of this study is that we cannot define the relative contribution of free uPA generated over 80 min vs. subsequent formation αM/uPA complexes to the clearance of pleural adhesions after IPFT. Despite this limitation, the results (Figs. 1–7, summarized in Fig. 8) suggest that both aspects of the intrapleural processing of scuPA contribute to durable PA activity and to the outcome of IPFT. Despite the differences in the composition of αMs between rabbit and human (4, 52), the results reported here otherwise support the contribution of endogenous αMs to successful IPFT in rabbits with TCN-induced pleural injury and demonstrate that similar mechanisms may be operative in humans. The pharmacokinetic analyses of intrapleural scuPA in TCN-induced injury in rabbits could differ from that in infectious pleural injury in humans, given the inherent limitations of the model including the absence of comparable loculations, bacterial burden, and antibiotics or variations in other potential confounders including PF pH. Thus future clinical trial testing would be required to demonstrate whether the processing of scuPA (27, 29, 30) in this animal model is recapitulated in PFs of patients with either loculated pleural infection or malignancy-induced loculation and impaired PF drainage.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grant P50 HL107186-02 and the Texas Lung Injury Institute, UTHSCT.

DISCLOSURES

S. Idell has a conflict of interest to declare, as The University of Texas Horizon Fund recently invested $500,000 in a start-up company called Lung Therapeutics, which was created to commercialize scuPA for intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy. The investment was made after the NHLBI funded the cGMP manufacturing of scuPA, Investigational New Drug/-enabling toxicology and regulatory support of the project. The organization of the company is incomplete at this time, but Dr. Idell will assume an equity position once the distribution is signed by all equity/royalty partners, which include Dr. Idell, Dr. Andrew Mazar of Northwestern University, a CEO who will be hired, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler, and The University of Texas Horizon Fund. Dr. Idell assumes full responsibility for the work, had access to all the data, and controlled the decision to publish. No other members of the authorship have conflicts of interest to declare, and the work presented here is part of the NIH CADET project on which Drs. Idell and Komissarov serve as principal investigators.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.A.K. conception and design of research; A.A.K., G.F., A.A., and S.K. performed experiments; A.A.K. and G.F. analyzed data; A.A.K., G.F., and A.K.K. interpreted results of experiments; A.A.K. and G.F. prepared figures; A.A.K. and G.F. drafted manuscript; A.A.K. and S.I. approved final version of manuscript; G.F., A.A., S.K., A.K.K., and S.I. edited and revised manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, Sacco RL, Teal P. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed.). Chest 133: 630S–669S, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aleman C, Alegre J, Monasterio J, Segura RM, Armadans L, Angles A, Varela E, Ruiz E, Fernandez de Sevilla T. Association between inflammatory mediators and the fibrinolysis system in infectious pleural effusions. Clin Sci (Lond) 105: 601–607, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allport LE, Butcher KS. Thrombolysis for concomitant acute stroke and pulmonary embolism. J Clin Neurosci 15: 917–920, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banbula A, Chang LS, Beyer WF, Bohra CL, Cianciolo GJ, Pizzo SV. The properties of rabbit alpha1-macroglobulin upon activation are distinct from those of rabbit and human alpha2-macroglobulins. J Biochem 138: 527–537, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett AJ. Alpha 2-macroglobulin. Methods Enzymol 80: 737–754, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett AJ, Starkey PM. The interaction of alpha 2-macroglobulin with proteinases. Characteristics and specificity of the reaction, and a hypothesis concerning its molecular mechanism. Biochem J 133: 709–724, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borth W. Alpha 2-macroglobulin, a multifunctional binding protein with targeting characteristics. FASEB J 6: 3345–3353, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouros D, Tzouvelekis A, Antoniou KM, Heffner JE. Intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy for pleural infection. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 20: 616–626, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron R, Davies HR. Intra-pleural fibrinolytic therapy vs. conservative management in the treatment of adult parapneumonic effusions and empyema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD002312, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collen D, Lu HR, Lijnen HR, Nelles L, Stassen JM. Thrombolytic and pharmacokinetic properties of chimeric tissue-type and urokinase-type plasminogen activators. Circulation 84: 1216–1234, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corcoran JP, Hallifax R, Rahman NM. New therapeutic approaches to pleural infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis 26: 196–202, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decologne N, Kolb M, Margetts PJ, Menetrier F, Artur Y, Garrido C, Gauldie J, Camus P, Bonniaud P. TGF-beta1 induces progressive pleural scarring and subpleural fibrosis. J Immunol 179: 6043–6051, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellison J, Thomson AJ, Conkie JA, McCall F, Walker D, Greer A. Thromboprophylaxis following caesarean section—a comparison of the antithrombotic properties of three low molecular weight heparins—dalteparin, enoxaparin and tinzaparin. Thromb Haemost 86: 1374–1378, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feinman RD, Wang D, Windwer SR, Wu K. The role of enzyme lysyl amino groups in the reaction with alpha 2-macroglobulin. Ann NY Acad Sci 421: 178–187, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman SR, Ney KA, Gonias SL, Pizzo SV. In vitro binding and in vivo clearance of human alpha 2-macroglobulin after reaction with endoproteases from four different classes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 114: 757–762, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher AP, Biederman O, Moore D, Alkjaersig N, Sherry S. Abnormal plasminogen-plasmin system activity (fibrinolysis) in patients with hepatic cirrhosis: its cause and consequences. J Clin Invest 43: 681–695, 1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganrot PO. Variation of the alpha 2-macroglobulin homologue with age in some mammals. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 21: 177–181, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonias SL, Balber AE, Hubbard WJ, Pizzo SV. Ligand binding, conformational change and plasma elimination of human, mouse and rat alpha-macroglobulin proteinase inhibitors. Biochem J 209: 99–105, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada S, Dannenberg AM, Jr, Vogt RF, Jr, Myrick JE, Tanaka F, Redding LC, Merkhofer RM, Pula PJ, Scott AL. Inflammatory mediators and modulators released in organ culture from rabbit skin lesions produced in vivo by sulfur mustard III Electrophoretic protein fractions, trypsin-inhibitory capacity, alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor, and alpha 1- and alpha 2-macroglobulin proteinase inhibitors of culture fluids and serum. Am J Pathol 126: 148–163, 1987 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardaway RM, Harke H, Williams CH. Fibrinolytic agents: a new approach to the treatment of adult respiratory distress syndrome. Adv Ther 11: 43–51, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardaway RM, Williams CH, Marvasti M, Farias M, Tseng A, Pinon I, Yanez D, Martinez M, Navar J. Prevention of adult respiratory distress syndrome with plasminogen activator in pigs. Crit Care Med 18: 1413–1418, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harpel PC, Mosesson MW. Degradation of human fibrinogen by plasma alpha2-macroglobulin-enzyme complexes. J Clin Invest 52: 2175–2184, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedstrom L. Serine protease mechanism and specificity. Chem Rev 102: 4501–4524, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hekman CM, Loskutoff DJ. Kinetic analysis of the interactions between plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and both urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator. Arch Biochem Biophys 262: 199–210, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Idell S. Extravascular coagulation and fibrin deposition in acute lung injury. New Horiz 2: 566–574, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Idell S. The pathogenesis of pleural space loculation and fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 14: 310–315, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Idell S, Azghani A, Chen S, Koenig K, Mazar A, Kodandapani L, Bdeir K, Cines D, Kulikovskaya I, Allen T. Intrapleural low-molecular-weight urokinase or tissue plasminogen activator vs. single-chain urokinase in tetracycline-induced pleural loculation in rabbits. Exp Lung Res 33: 419–440, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Idell S, Girard W, Koenig KB, McLarty J, Fair DS. Abnormalities of pathways of fibrin turnover in the human pleural space. Am Rev Respir Dis 144: 187–194, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Idell S, Jun NM, Liao H, Gazar AE, Drake W, Lane KB, Koenig K, Komissarov A, Tucker T, Light RW. Single-chain urokinase in empyema induced by Pasturella multocida. Exp Lung Res 35: 665–681, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Idell S, Mazar A, Cines D, Kuo A, Parry G, Gawlak S, Juarez J, Koenig K, Azghani A, Hadden W, McLarty J, Miller E. Single-chain urokinase alone or complexed to its receptor in tetracycline-induced pleuritis in rabbits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 920–926, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Idell S. Update on the use of fibrinolysins in pleural disease. Clin Pulm Med 12: 184–190, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karandashova S, Florova G, Azghani AO, Komissarov AA, Koenig K, Tucker TA, Allen TC, Stewart K, Tvinnereim A, Idell S. Intrapleural adenoviral delivery of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 exacerbates tetracycline-induced pleural injury in rabbits. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 48: 44–52, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim HS, Patra A, Paxton BE, Khan J, Streiff MB. Catheter-directed thrombolysis with percutaneous rheolytic thrombectomy vs. thrombolysis alone in upper and lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 29: 1003–1007, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komissarov AA, Florova G, Idell S. Effects of extracellular DNA on plasminogen activation and fibrinolysis. J Biol Chem 286: 41949–41962, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komissarov AA, Mazar AP, Koenig K, Kurdowska AK, Idell S. Regulation of intrapleural fibrinolysis by urokinase-α-macroglobulin complexes in tetracycline-induced pleural injury in rabbits. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L568–L577, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Komissarov AA, Stankowska D, Krupa A, Fudala R, Florova G, Florence J, Fol M, Allen TC, Idell S, Matthay MA, Kurdowska AK. Novel aspects of urokinase function in the injured lung: role of α2-macroglobulin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L1037–L1045, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maskell NA, Davies CW, Nunn AJ, Hedley EL, Gleeson FV, Miller R, Gabe R, Rees GL, Peto TE, Woodhead MA, Lane DJ, Darbyshire JH, Davies RJUK. Controlled trial of intrapleural streptokinase for pleural infection. N Engl J Med 352: 865–874, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Midde KK, Batchinsky AI, Cancio LC, Shetty S, Komissarov AA, Florova G, Walker KP, III, Koenig K, Chroneos ZC, Allen T, Chung K, Dubick M, Idell S. Wood bark smoke induces lung and pleural plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and stabilizes its mRNA in porcine lung cells. Shock 36: 128–137, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsson T, Wallen P, Mellbring G. In vivo metabolism of human tissue-type plasminogen activator. Scand J Haematol 33: 49–53, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parikh S, Motarjeme A, McNamara T, Raabe R, Hagspiel K, Benenati JF, Sterling K, Comerota A. Ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis: initial clinical experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol 19: 521–528, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Philip-Joet F, Alessi MC, Philip-Joet C, Aillaud M, Barriere JR, Arnaud A, Juhan-Vague I. Fibrinolytic and inflammatory processes in pleural effusions. Eur Respir J 8: 1352–1356, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pizzo SV, Rajagopalan S, Roche PA, Fuchs HE, Feldman SR, Gonias SL. Specificity of alpha 2-macroglobulin covalent cross-linking for the active domain of proteinases. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 367: 1177–1182, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahman NM, Maskell NA, West A, Teoh R, Arnold A, Mackinlay C, Peckham D, Davies CW, Ali N, Kinnear W, Bentley A, Kahan BC, Wrightson JM, Davies HE, Hooper CE, Lee YC, Hedley EL, Crosthwaite N, Choo L, Helm EJ, Gleeson FV, Nunn AJ, Davies RJ. Intrapleural use of tissue plasminogen activator and DNase in pleural infection. N Engl J Med 365: 518–526, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogers WJ, Bowlby LJ, Chandra NC, French WJ, Gore JM, Lambrew CT, Rubison RM, Tiefenbrunn AJ, Weaver WD. Treatment of myocardial infarction in the United States (1990 to 1993). Observations from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 90: 2103–2114, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salvesen GS, Sayers CA, Barrett AJ. Further characterization of the covalent linking reaction of alpha 2-macroglobulin. Biochem J 195: 453–461, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schved JF, Gris JC, Gilly D, Joubert P, Eledjam JJ, d'Athis F. [Fibrinolytic activity in traumatic hemothorax fluids]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 10: 104–107, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sisson TH, Simon RH. The plasminogen activation system in lung disease. Curr Drug Targets 8: 1016–1029, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sottrup-Jensen L. Alpha-macroglobulins: structure, shape, and mechanism of proteinase complex formation. J Biol Chem 264: 11539–11542, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stefanutti G, Ghirardo V, Barbato A, Gamba P. Evaluation of a pediatric protocol of intrapleural urokinase for pleural empyema: a prospective study. Surgery 148: 589–594, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Straight DL, Hassett MA, McKee PA. Structural and functional characterization of the inhibition of urokinase by alpha 2-macroglobulin. Biochemistry 24: 3902–3907, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strickland DK, Gonias SL, Argraves WS. Diverse roles for the LDL receptor family. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13: 66–74, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamamizu S, Miyake Y, Ito T, Sinohara H. Changes in trypsin-binding properties and conformation of rabbit alpha-2-macroglobulin on reaction with methylamine. J Biochem 105: 898–904, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thorsen S, Philips M, Selmer J, Lecander I, Astedt B. Kinetics of inhibition of tissue-type and urokinase-type plasminogen activator by plasminogen-activator inhibitor type 1 and type 2. Eur J Biochem 175: 33–39, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]