Abstract

Objectives

While health-related stigma has been the subject of considerable research in other conditions (obesity and HIV/AIDS), it has not received substantial attention in diabetes. The aim of the current study was to explore the social experiences of Australian adults living with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), with a particular focus on the perception and experience of diabetes-related stigma.

Design

A qualitative study using semistructured interviews, which were audio recorded, transcribed and subject to thematic analysis.

Setting

This study was conducted in non-clinical settings in metropolitan and regional areas in the Australian state of Victoria. Participants were recruited primarily through the state consumer organisation representing people with diabetes.

Participants

All adults aged ≥18 years with T2DM living in Victoria were eligible to take part. Twenty-five adults with T2DM participated (12 women; median age 61 years; median diabetes duration 5 years).

Results

A total of 21 (84%) participants indicated that they believed T2DM was stigmatised, or reported evidence of stigmatisation. Specific themes about the experience of stigma were feeling blamed by others for causing their own condition, being subject to negative stereotyping, being discriminated against or having restricted opportunities in life. Other themes focused on sources of stigma, which included the media, healthcare professionals, friends, family and colleagues. Themes relating to the consequences of this stigma were also evident, including participants’ unwillingness to disclose their condition to others and psychological distress. Participants believed that people with type 1 diabetes do not experience similar stigmatisation.

Conclusions

Our study found evidence of people with T2DM experiencing and perceiving diabetes-related social stigma. Further research is needed to explore ways to measure and minimise diabetes-related stigma at the individual and societal levels, and also to explore perceptions and experiences of stigma in people with type 1 diabetes.

Keywords: Social Medicine, Public Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This qualitative study is the first to describe, in detail, the perceptions and experiences of diabetes-related stigma from the perspective of adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

While the small sample size may limit the representativeness of the findings, efforts were made to include a broad cross-section of adults with T2DM and data saturation was achieved.

All participants were members of the state organisation representing people with diabetes and most were tertiary educated. These people may be more engaged in their diabetes care and in diabetes issues than the general population of adults with diabetes.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) affects more than 220 million worldwide and is increasing in prevalence.1 More than one million Australians have diabetes, with most of these having T2DM.2 Its physical impact is well documented, with diabetes management and complications having substantial implications for individual and societal health, psychological well-being and quality of life, as well as for the global economy.3–7 In the past decade, landmark studies have demonstrated that T2DM can be prevented,8 9 highlighting the role of behaviour and personal responsibility in the development of the condition. As the increasing prevalence of T2DM has achieved prominence in the media and in the consciousness of the general public, perceptions of T2DM appear to be changing, with anecdotal evidence of social stigma and discrimination apparent (eg, public comments posted online in response to articles in the media10). While the fact that the person has T2DM may not be immediately evident, certain risk factors (eg, obesity) and the need for daily self-management (eg, medication taking, checking blood glucose, modifying diet and injecting insulin) may be conspicuous to others and lead to undesirable consequences such as stigmatisation. Health-related social stigma is a negative social judgement based on a feature of a condition or its management that may lead to perceived or experienced exclusion, rejection, blame, stereotyping and/or status loss.11 12 Stigma has been extensively researched in other conditions such as obesity13–16 and HIV/AIDS,17–19 but has yet to be the focus of a systematic programme of research in diabetes.

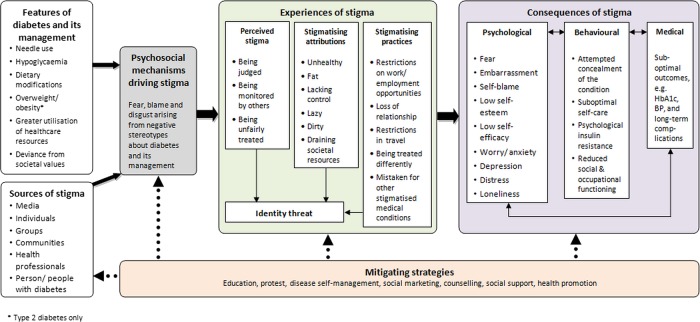

Our recent review20 highlighted the lack of research about stigma in diabetes, but did find some evidence that people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and T2DM perceive and experience diabetes-related stigma and that this stigma has negative consequences across many aspects of their life. We proposed a framework (a revised version of which is illustrated in figure 1) for understanding diabetes-related stigma that hypothesised the features of diabetes and its management that may be the focus of this phenomenon, the sources and psychological mechanisms driving it, and the possible experiences and consequences of stigma.20

Figure 1.

A revised framework to understand diabetes-related stigma.

A necessary starting point for building on the findings of this review and starting a research programme in this area is to conduct an in-depth exploration of the perceptions and experiences of diabetes-related stigma from the perspective of the person living with the condition.21 This will provide a comprehensive understanding of perceived diabetes-related stigma to inform quantitative surveys of people with and without diabetes, and lead to the development, evaluation and implementation of intervention strategies to reduce stigma. We conducted an interview study with the aim of exploring the social experiences of Australian adults living with T2DM, with a particular (but concealed) focus on the perception and experience of diabetes-related stigma.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

Adults aged ≥18 years with T2DM who spoke English and who lived in the Australian state of Victoria were eligible to take part in this interview study. Participants were recruited into this study primarily from the membership list of Diabetes Australia—Vic (DA—Vic; peak consumer body and leading charity representing people affected by diabetes in Victoria, Australia). The study was also advertised statewide in diabetes-related media and social media. The study was advertised as an investigation of ‘the social experience of living with type 2 diabetes’. Study advertisements purposefully did not refer to ‘stigma’ in order to minimise the risk of inadvertently attracting only participants with extreme negative experiences (which would have resulted in unrepresentative data) and to avoid biasing participants’ interview responses.

A total of 147 people enquired about the study by telephone or email: 108 were emailed or posted study information sheets; 39 made contact only after recruitment had closed. Purposive selection was used to ensure that the sample reflected a wide range of ages, a gender balance and a combination of people from metropolitan and regional areas. We aimed to recruit 20 people into the study, with the possibility of conducting additional interviews, if necessary, to achieve data saturation. No new themes emerged after (and therefore data saturation was achieved at) participant #11 (see table 2), though purposive recruitment continued to ensure a sufficiently varied sample. Ultimately, 26 people were recruited and took part in interviews. One participant (#6) was subsequently excluded on the basis that he had not received a diagnosis of T2DM (which became evident during the interview), and because he presented with cognitive impairment. One participant (#20) made it known to the research team after the study had been completed that her diagnosis had been revised to T1DM, though it was clear that her presentation was atypical. However, we decided to retain her data in this study as, at the time of participation, she had a diagnosis of T2DM and she believed that she had this condition, and so her social experiences of living with the condition were as real as those of the other participants. Thus, this article reports on data from 25 interviews.

Table 2.

Themes and subthemes, and demonstration of data saturation

| ID | Evidence of stigma |

Sources of stigma |

Consequences of stigma |

Comparisons with type 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blame and shame | Negative stereotyping | Discrimination/restricted opportunities | Media | Healthcare professionals | Family/friends/colleagues | Unwillingness to disclose | Emotional distress | ||

| 1 | ✓ | ||||||||

| 2 | ✓ | ||||||||

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 13 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 16 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 17 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 18 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 22 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 26 | ✓ | ||||||||

Participant 6 was excluded from the analysis.

Interview schedule and procedure

Informed by our literature review,20 we developed a semistructured interview schedule to elicit participant narratives of perceived or experienced diabetes-related stigma. Indirect questioning (ie, not explicitly referring to ‘stigma’) invited participants to discuss their own social experience in a range of contexts, including healthcare settings, the workplace, their social and/or family environments and in the media. Interviewers did not use the word ‘stigma’ until either the participant had used it spontaneously or until the last question to address this concept directly. This approach was used to avoid confusing participants with jargon, and to avoid introducing bias in the questioning, thus maximising opportunities for participants to discuss their positive and negative social experiences.

All interviews were conducted between May and July 2012 in non-clinical settings by interviewers with a background in health psychology (JLB, AV and JS). A selection of interviews (four) were conducted by one interviewer and observed by another for the purposes of enabling reflective discussions about the interviews and the role and influence of the interviewer in each one, as well as to identify any potential bias or stereotypes about T2DM that the interviewer may hold. Interviewers also wrote notes and reflections immediately after every interview. All interviews were audio recorded and lasted an average of 55 min (range 25–103 min). At the conclusion of the interview, participants completed a short questionnaire to provide demographic and clinical information. All participants received a $A20 department store gift voucher as a token of appreciation for participating.

Transcription and analysis

All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. The research team checked each transcript against the recording for accuracy. The deidentified transcripts were imported into NVivo V.10 to facilitate data coding, retrieval and analysis.

A thematic analysis using an inductive (data driven) approach was used to examine the data.22 Two researchers (JLB and AV, both with postgraduate qualifications in health psychology and training and experience in qualitative interviewing) read and reread the transcripts to develop two initial coding frameworks, which were then compared across coders and reviewed by the full authorship team. Following the revision, an integrated framework was developed and piloted (by JLB and AV) by independently coding a random selection of four transcripts. Final modifications were made to improve utility and comprehensibility. Using the final coding framework, JLB and AV then coded two transcripts collaboratively to ensure agreement on coding rules, and then coded five additional transcripts independently. Intercoder agreement for each code was determined by summing the percentage of content in each code identified by both coders and the percentage of content in each code identified by neither coder. A mean agreement rating (averaging agreement ratings across codes) of 99.5% was achieved for these five transcripts, indicating a high level of consistency in coding decisions. Minor discrepancies (eg, where AV had coded data into codes A and B, whereas JLB had coded only into code A) were resolved through discussion, raising the agreement level to 100%. AV then coded the remaining 17 transcripts independently.

The content of each code was then examined by all authors to determine whether some codes could be subsumed by others due to overlapping content, and to explore relationships between codes. For the purposes of this analysis, we coded according to the key topics described below. Participant quotes are provided to illustrate our findings.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the final sample of 25 participants, 12 (48%) were women. The median age was 61 years (range 22–79 years; IQR=15.00), and T2DM duration was 5 years (range 0–29 years; IQR=7.25). These characteristics are representative of Australian adults with T2DM as documented in a large-scale national survey.23 Further sample characteristics are displayed in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (N=25)

| Sample characteristics | Median (IQR) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age: years | 61 (15.00) |

| Diabetes duration: years | 5 (7.25) |

| Gender: women | 12 (48) |

| Primary treatment | |

| Insulin injections | 5 (20) |

| Oral hypoglycaemic agents | 14 (56) |

| Lifestyle | 6 (24) |

| Highest qualification | |

| School or intermediate certificate | 1 (4) |

| High school or leaving certificate | 2 (8) |

| Trade/apprenticeship | 2 (8) |

| Certificate/diploma | 4 (16) |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 16 (64) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time work | 6 (24) |

| Part-time work | 7 (28) |

| Retired/not working | 12 (48) |

| Living in a metropolitan region | 19 (76) |

| English language | 25 (100) |

Perceptions of social stigma

When asked explicitly, 15 participants (60%) indicated that they believed there was social stigma surrounding T2DM. Some gave specific examples of personally experiencing or feeling the effects of diabetes-related stigma, while others described it as something they perceived in society generally or that others with T2DM experienced. One woman described the personal experience of stigma as follows

I think the stigma is that it's a lifestyle disease. That somehow you've been lazy and you've allowed this to happen to yourself. I think to me that must come through very strongly, that's the judgment that I think that is made. (#19; woman, 54 years)

Ten (40%) participants believed there was no stigma surrounding T2DM but 6 of these had already described evidence of diabetes-related stigma throughout the interview. Four indicated that they firmly believed there was no stigma and that they were surprised that this was a topic of interest, as they had never experienced it or considered it to be an issue. Interestingly, these four were some of the oldest participants in the study (aged 67–73).

I don’t believe there would be any stigma at all to having type 2 diabetes. I just can’t imagine how it would arise (#13; man, 69 years)

Two people felt that while obesity was stigmatised, T2DM was not, and any stigma that people with T2DM experienced was due to their weight alone.

Their appearance might be fat, they might look unhealthy and, when they’re applying for jobs or trying to interact socially that might be the main reason they’ve got a stigma rather than the diabetes. (#1, man, 67 years)

In contrast, others raised the issue of diabetes-related stigma unprompted during the initial stages of the interview. For example, when asked the first question about what it was like to be diagnosed with T2DM, one woman responded

I thought then, and I still think now, that there is still somehow a feeling of stigma attached to getting type 2 diabetes because you feel it’s your fault and you did it to yourself, so initially I was very upset. (#5, woman, 59 years)

Each of the key themes and subthemes are explored in more detail below, and the structure of these key themes is summarised in table 2, with indications of which participants discussed which themes. Evidence of diabetes-related stigma was reflected in participants’ accounts of blame and shame, being associated with negative stereotypes, discrimination and restriction of opportunities. The media, healthcare professionals, family and friends were identified as sources of stigma and stigmatising practices. Many participants compared their own experiences unfavourably with those who have T1DM.

Evidence of diabetes-related stigma

Blame and shame

The concepts of blame and shame were highly salient. Participants described feeling judged and blamed by others for bringing T2DM on themselves through overeating, poor dietary habits, being inactive or being overweight. There was a sense that this reflected negatively on their personal character.

There's this message that diabetes is this terrible thing that terrible people get because they do terrible things (#11, woman, 61 years)

While perceptions of blame were described by most as a general perception of society's views, some described specific instances of their direct experiences of this blame, for example

I find a lot of people, they like to think of you as being the culprit. In fact I actually had one person say ‘well you've dug your grave with your own teeth’. (#12, man, 67 years)

Self-blame and feeling guilty for having developed T2DM was common, though it was unclear whether this was the result of internalising perceived societal attitudes, or whether self-blame influenced the perception of attitudes. Some participants who had a strong family history of T2DM, as well as some who reported a healthy lifestyle and were not visibly overweight, still had a strong sense that there was something they should have done to avoid developing the condition.

I felt guilty in the early days for the first, probably 10 to 15 years, I felt guilty because it was my fault. (#14, woman, 59 years)

Negative stereotyping

Every participant spoke of negative stereotypes being associated with T2DM. Some of the most common negative stereotypes that were used or described were fat, obese, overweight, big fat pig, lazy, slothful, couch potato, over-eater and glutton. Once again, these stereotypes reflected the idea that you brought it on yourself. Less frequently reported were stereotypes of people with T2DM being poor people, not terribly intelligent, as well as being a shocking person or bad person and injecting insulin. Responses to these stereotypes were mixed. Some people expressed concern, frustration or unease about being automatically labelled in this way, while others endorsed the stereotypes themselves.

Discrimination and restricted opportunities

While very few examples of discrimination were reported, there were a few notable cases. For instance, one woman (who stated a strong desire to have a child) described restrictions against people with diabetes who want to become adoptive parents.

I looked up the adoption [criteria]…a couple of the countries said ‘no type 1 or type 2 diabetes’…I suppose if adoption agencies are saying no diabetes then that's not going to happen. (#16, woman, 35 years)

More prominent than discrimination per se was a sense of restricted or lost opportunities in life as a result of having T2DM. Limitations in travel or career prospects, and lapsed friendships with people who were unsupportive were described as examples of the negative impact T2DM has on life opportunities. For example, one woman described how T2DM had affected her pursuit of career advancement.

I guess it did sort of stop me from pushing myself as much as I usually do, so I did leave the position at a time when I was really enjoying it and was hoping to better myself in that position (#23, woman, 37 years)

Sources of stigma

Media

While some participants could not recall any specific media stories or campaigns about T2DM, those participants who could held one of two key views. The first view was that the emphasis on T2DM being a lifestyle disease, and therefore within an individual's control, was a helpful and socially responsible preventative health message.

I think it’s great the emphasis they have at the moment talking about your lifestyle and your diet, exercise and that sort of thing. I think it’s very, very good (#2, man, 73 years)

The second view was that the emphasis on lifestyle factors (such as being overweight or physically inactive) as causal in T2DM served to generate or reinforce blaming attitudes in the community, perpetuate negative stereotypes and elicit negative emotional reactions from people with T2DM.

I don’t want people to think I developed this disease because I was some big fat that never got off her chair…I was active, exercised, worked, everything…it doesn’t have to be from your lifestyle but I think most, well that’s how they portray it in the media…they show all the time ‘there’s this diabetics epidemic’ and all you see is fat people, not their heads, these big bums and tummies and all that and you think ‘do people think I was like that, that I looked like that?’ (#15, woman, 60 years)

Those who firmly believed that there was a stigma surrounding T2DM were more likely to critique the media's approach to T2DM in this way. Participants who held this view also described sensationalism in the media around the T2DM epidemic, and expressed dissatisfaction with the scare tactics often used in public health campaigns. They wanted more positive messages about living with diabetes to be incorporated into the media.

There’s no good news stories about type 2 diabetes. Perhaps there should be. Perhaps it should be ‘it isn’t necessarily a death sentence’. (#3, man, 54 years)

Healthcare professionals

Most participants described a combination of positive/helpful and negative/discouraging interactions with healthcare professionals. Some participants reported stigmatising practices and attitudes among healthcare professionals, who were seen to focus on what was being done ‘wrong’ (eg, failure to lose weight or reduce glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) since the last consultation) rather than finding ways to encourage behaviour change efforts. This was experienced as discouraging and judgemental.

The dietician was awful…she asked me if I exercise and I said ‘I do the gym twice a week and I have consistently since November’ ‘that's not enough, you need to go five times a week’…this makes me really angry (#16, woman, 35 years)

These negative experiences with healthcare professionals led to changing providers, seeking advice from other sources (eg, friends and the internet) and avoidance of consultations with healthcare professionals.

Family, friends and colleagues

While, in general, participants reported that they had supportive families, friends and workplaces (where relevant), most described at least one example of unhelpful, annoying or discouraging behaviour from their families or peers. This behaviour was described as being hurtful, judgemental and interfering, particularly regarding dietary choices and weight management.

I just say to them ‘I know what I can put in my mouth and what I can't, thanks all the same’…‘I'd love it if you offer me what you're handing around and I can say ‘yes’ or ‘no thanks’, that would be nice really’. That makes me feel excluded. (#25, woman, 59 years)

Consequences of stigma

Unwillingness to disclose condition

Participants tended to describe specific times in their diabetes journey, or specific people or circumstances that made them reluctant to disclose their condition. Common examples included the period soon after diagnosis, a particular family member or friend they anticipated would respond unhelpfully, or during a job interview or in the workplace, for example

I think the problem was more in corporate life…I was in a very senior role and I felt the need to hide it from that particular situation. (#24, woman, 68 years).

The key reasons for non-disclosure were fear of being judged or blamed for having T2DM or an overwhelming sense of self-blame. Some also described a fear of being discriminated against or a desire to distance oneself from society's negative portrayals of people with diabetes.

When I first got it I wouldn't tell anybody. I didn't even tell my husband. I told nobody. I actually felt so ashamed to have diabetes. I felt completely ashamed of myself. (#19, woman, 54 years)

Apart from me, none of the people I know [who] have diabetes ever say they have diabetes, they never say it, they never speak up, they never say a word and I reckon it's because the messages that are put out by [patient organisation] are shutting them up because they're hurt and are mortified. (#22, man, 56 years)

Other reasons included not wanting to deal with people's misconceptions about the condition (particularly around the dietary management), and not wanting to answer lots of questions about diabetes, worry or shock people, or attract sympathy.

However, many participants were not concerned about other people knowing they had T2DM. This was particularly true of older participants, perhaps because, as one man commented, living with diabetes was a relatively common experience among their peers.

It's a non-issue really…most of my colleagues are of the same age as I am and many of them have relatives or spouses or people who are diabetic (#12, man, 67 years).

Reasons for disclosure included helping other people understand more about diabetes, explaining self-management behaviour or dietary choices in public, seeking support and for safety in case of a medical emergency.

Psychological distress

The psychological consequences of stigma included emotional distress such as shame, guilt, regret and hopelessness. Other psychological consequences that were frequently noted included feelings of low self-worth and self-confidence. Some participants felt that having T2DM reflected poorly on their personal character. The psychological distress experienced made it even harder to cope with and adjust to life with T2DM.

I felt a little bit inferior (#14, woman, 59 years)

I call it the ‘blame and shame disease’ because I think that people get blamed and shamed and I think that makes it worse…they feel hopeless. (#11, woman, 61 years)

Comparisons with T1DM

There was a distinct feeling among participants that social stigma was specific to T2DM, and that those with T1DM were not judged so harshly. The main reason suggested for this was that those with T1DM were not perceived to be at fault or to have done anything to cause their condition. Other reasons included that T1DM is perceived to be a more serious condition than T2DM because T1DM is often associated with a diagnosis in childhood. One man identified the difference as

Type 1 is ‘you poor thing’, type 2 is ‘you stupid thing’ (#4, man, 57 years)

It was also perceived that people with T1DM received more support and assistance than people with T2DM, which results in a division between these two groups.

But they're [people with type 1 diabetes] generally quite looked after. They have access to pumps, they have heaps of support groups out there and workshops…if I tried to get into the same type of thing because I'm on insulin they say “no, because you're type 2” so they automatically exclude you just because of your diagnosis and not because of the way you're managing your diabetes. So that segregates the diabetes community as a whole. (#20, woman, 22 years)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first qualitative investigation of the experiences and perceptions of diabetes-related stigma from the perspective of people living with T2DM. Based on commonly used definitions of health-related stigma, we defined diabetes-related stigma to be an adverse social judgement based on a feature of diabetes or its management that may lead to perceived or experienced exclusion, rejection, blame, stereotyping and/or status loss.11 12 Our findings indicate that stigmatising attitudes and practices, consistent with this definition, are part of the social experience of living with T2DM.

Evidence of T2DM-related stigma

All participants bar four either explicitly identified a social stigma surrounding T2DM or described evidence of this stigma. Those who did not were some of the oldest participants in the study, suggesting that perhaps younger people with T2DM are more likely to experience, or be sensitive to, diabetes-related stigma. Younger adults with T2DM face many pressures unique to their age group and perceive that existing T2DM services are not relevant to them.24 These factors may contribute to the more pronounced stigma experienced by younger participants. Examples of this stigma given by participants included blaming and shaming attitudes towards those with T2DM (including self-blame), negative stereotyping, discrimination and lost opportunities as a result of having T2DM. While the well-recognised obesity stigma16 25 26 was seen to play some part in diabetes-related stigma, the latter cannot be wholly explained by the former.

While study participants reserved their most scathing criticism for the media, the people with whom participants had personal relationships were also described as contributing to the diabetes-related stigma. Consistent with previous research in obesity,26 27 this was particularly evident with regard to interactions with healthcare professionals. Comments or behaviour that revealed judgement, blame or other negative attitudes towards the person with T2DM were remembered by many participants, sometimes years later. Participants described not returning for a repeat consultation as a direct result of these interactions.

Consistent with previous research,28–30 perceiving and experiencing diabetes-related stigma had behavioural and psychological consequences. Participants described an unwillingness to disclose their T2DM to others, which has potentially dangerous ramifications for medical emergencies. An unwillingness to disclose also raises the possibility that essential self-care will be compromised (eg, skipping or delaying medications/insulin, not checking blood glucose levels, and succumbing to social pressure to eat unhealthy foods) or undertaken in unhygienic environments (eg, public toilets) to avoid being noticed.

People also described strong feelings of low self-worth and self-esteem, shame and guilt in response to the perceived or experienced stigma. Previous research has demonstrated the associations between emotional distress and suboptimal self-management and ultimately poorer physical health outcomes.5 31–33 Therefore, the potential consequences of stigma are perhaps even more far-reaching than those described by our study participants.

Framework of diabetes-related stigma

The findings from this study lend support to our proposed model of diabetes-related stigma.20 Consistent with our model, people with T2DM identified individuals in their lives, including healthcare professionals, as sources of stigma. However, our proposed model did not capture the role of the media in driving and reinforcing diabetes-related stigma, which was a key concern for participants in this study, raised spontaneously and in response to direct questioning. In figure 1, we propose a revised model of diabetes-related stigma to include this important issue. While self-blame and blame by others was a key theme identified in the current study and a driving mechanism of stigma described in our model, other mechanisms included in our model were less evident (eg, fear and disgust).

The examples and evidence of stigma identified in this study are also consistent with those proposed in the model (eg, stereotyping, discrimination/restrictions and being judged), as are some of the psychological and behavioural consequences of stigma. On the whole, the proposed model continues to provide a useful ‘road map’ for diabetes-related stigma research, though some minor modifications (eg, including media as a source of stigma) are warranted in light of the current study's findings.

Implications and future directions

Our findings indicate that not only is obesity-related stigma likely to be a barrier to diabetes management in a healthcare setting,34 but also diabetes-specific stigma may be an additional barrier. This was illustrated by the fact that much of what was discussed by participants was specific to have T2DM, and not about being overweight or obese. Given that the obesity and diabetes stigmas are not one and the same, further research into diabetes-related stigma is required, and we cannot solely rely on the obesity stigma literature to inform future work in diabetes. Considerable research has already been undertaken with regard to understanding, combating or minimising the impact of the obesity stigma in healthcare or health education settings.34–37 Similar work is now needed in diabetes, with a view in conducting research that examines the correlates and outcomes of diabetes-related stigma for the person living with the condition, using findings to inform antistigma interventions in healthcare settings, and influencing the way T2DM is portrayed in the media. We have previously commented on the unintended negative consequences of a sole emphasis on the role of individual responsibility with regard to obesity and associated conditions such as T2DM.10 In any antistigma intervention, attention will need to be paid to the subtle distinction between empowerment to take personal responsibility for diabetes self-care and blaming the individual for causing their own health problems.

Interventions for people with T2DM that focus on enhancing coping and resilience in the face of stigmatising attitudes and practices may be beneficial in terms of improving psychological outcomes and minimising barriers to optimal self-care. At a minimum, healthcare professionals need to consider stigmatisation as a possible issue that is causing distress that needs to be addressed.

Participants in this study did not perceive that people with T1DM were subject to stigmatising attitudes and practices, but that does not mean that people with T1DM do not perceive it to be a stigmatised condition. Research is needed to explore the social experiences of people with T1DM to enable comparison with the experiences reported by people with T2DM.

Limitations

As with all qualitative studies, the emphasis is on in-depth exploration of an issue or experience. Consequently, small sample sizes must be used, which may limit the representativeness of the findings. Care was taken to recruit a diverse sample and this was largely achieved, but people with a tertiary education were over-represented in the sample, and all were members of DA—Vic, the state's consumer organisation. These people may be more engaged in their diabetes care and in diabetes issues than the general population of adults with diabetes. Participants’ ethnicity was not recorded, and therefore the ethnic diversity of the sample cannot be assured. Future diabetes research in Australia would benefit from attempts to recruit ethnically diverse samples which better represent the community, and culturally sensitive collaboration with indigenous communities.38 However, this study has enabled the identification of issues to inform the design of a novel measure of diabetes-related social stigma, so that large-scale, representative quantitative studies can be undertaken.

Conclusions

This study is the first to examine in depth the perceptions and experiences of social stigma of adults living with T2DM. These findings indicate that stigmatisation is an issue of substantial concern for people with T2DM, and has harmful consequences. Future research needs to focus on how to dispel stigmatising attitudes and practices, particularly in healthcare settings, and how to minimise the impact of diabetes-related stigma by enhancing coping among people with T2DM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Diabetes Australia—Vic, particularly the membership team, for their assistance with recruitment for this study. They also thank all the people with diabetes who expressed an interest or took part in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: JS, JLB and KM conceptualised the study. AV, JLB and JS conducted the participant interviews. AV checked the transcripts against the audio files. AV and JLB developed the coding framework (in consultation with JS and KM) and conducted the data analysis. JLB prepared the first draft of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the development of the interview schedule, provided feedback and were responsible for subsequent revisions of the manuscript, and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: Core funding to The Australian Centre for Behavioural Research in Diabetes (ACBRD) derived from partnership between Diabetes Australia—Vic and Deakin University.

Competing interests: This research was supported by a project grant awarded to JLB, KM and JS from the Centre for Mental Health and Wellbeing Research, School of Psychology, Deakin University.

Ethics approval: Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2012-072).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:4–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AIHW Diabetes prevalence in Australia: detailed estimates for 2007–08. Canberra: AIHW, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HAW, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321:405–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature 2001;414:782–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, et al. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2001;63:619–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 1999;15:205–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang P, Zhang X, Brown J, et al. Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:293–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. New Engl J Med 2001;344: 1343–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet 2006;368: 1673–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browne JL, Zimmet P, Speight J. Individual responsibility for reducing obesity: the unintended consequences of well intended messages. Med J Aust 2011;195:386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol 2001;27:363–85 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med 2006;11:277–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agerström J, Rooth D-O. The role of automatic obesity stereotypes in real hiring discrimination. J Appl Psychol 2011;96:790–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diedrichs PC, Barlow FK. How to lose weight bias fast! Evaluating a brief anti-weight bias intervention. Br J Health Psych 2011;16:846–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacLean L, Edwards N, Garrard M, et al. Obesity, stigma and public health planning. Health Promot Int 2009;24:88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1019–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valdiserri RO. HIV/AIDS stigma: an impediment to public health. Am J Public Health 2002;92:341–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev 2003;15:49–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS 2008;22:S67–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schabert J, Browne JL, Mosely K, et al. Social stigma in diabetes: a framework to understand a growing problem for an increasing epidemic. Patient 2013;6:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medical Research Council (MRC) A framework for development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. London: MRC, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Speight J, Browne JL, Holmes-Truscott E, et al. Diabetes MILES—Australia (Management and Impact for Long-term Empowerment and Success): methods and sample characteristics of a national survey of the psychological aspects of living with type 1 or type 2 diabetes in Australian adults. BMC Public Health 2012;12:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Browne JL, Scibilia R, Speight J. The needs, concerns, and characteristics of younger Australian adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2013;30:620–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Psychosocial origins of obesity stigma: toward changing a powerful and pervasive bias. Obes Rev 2003;4:213–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636. Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity 2009;17:941-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas SL, Hyde J, Karunaratne A, et al. Being ‘fat’ in today's world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in Australia. Health Expect 2008;11:321–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiu ATY, Kwan JJYM, Wong RYM. Social stigma as a barrier to diabetes self-management: implications for multi-level interventions. J Clin Nurs 2003;12:149–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh H, Cinnirella M, Bradley C. Support systems for and barriers to diabetes management in South Asians and Whites in the UK: qualitative study of patients’ perspectives. BMJ Open 2012;2:pii: e001459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wellard SJ, Rennie S, King R. Perceptions of people with type 2 diabetes about self-management and the efficacy of community based services. Contemp Nurse 2008;29:218–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3278–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, et al. The relationship of depressive symptoms to symptom reporting, self-care and glucose control in diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:246–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications 2005;19:113–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teixeira ME, Budd GM. Obesity stigma: a newly recognized barrier to comprehensive and effective type 2 diabetes management. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2010;22:527–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz MB, Chambliss HO, Brownell KD, et al. Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obes Res 2003;11:1033–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Persky S, Eccleston CP. Impact of genetic causal information on medical students’ clinical encounters with an obese virtual patient: health promotion and social stigma. Ann Behav Med 2010;41: 363–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Brien KS, Hunter JA, Banks M. Implicit anti-fat bias in physical educators: physical attributes, ideology and socialization. Int J Obesity (Lond) 2007;31:308–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dussart F. Diet, diabetes and relatedness in a central Australian Aboriginal settlement: some qualitative recommendations to facilitate the creation of culturally sensitive health promotion initiatives. Health Promot J Austr 2009;20:202–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.