Abstract

Objective

Recent studies suggest that statins increase the risk of subsequent diabetes with a clear dose response effect. However, patients prescribed statins have a higher background risk of diabetes. This national cohort study aims to provide an estimate of the comparative risks for subsequent development of new-onset diabetes in adults prescribed statins and in those with an already higher background risk on cardiovascular risk-modifying drugs and a control drug.

Design

Longitudinal cohort study.

Setting

Use of routinely collected data from a complete national primary care electronic prescription database in New Zealand.

Participants

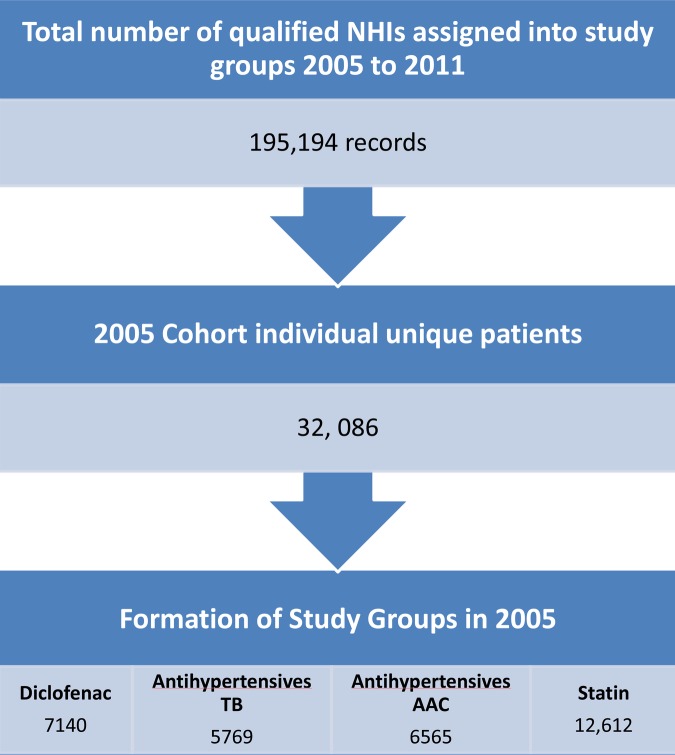

32 086 patients aged between 40 and 60 years in 2005 were eligible and assigned to four non-overlapping groups receiving their first prescription for: (1) diclofenac (healthy population) n=7140; (2) antihypertensives thought likely to induce diabetes (thiazides and β-blockers) n=5769; (3) antihypertensives thought less likely to induce diabetes (ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blocker) n=6565 and (4) statins n=12 612.

Outcome

Numbers of first metformin prescriptions were compared between these groups from 2006 to 2011.

Results

Patients prescribed statins have the highest risk of receiving a subsequent metformin prescription (HR 3.31; 95% CI 2.56 to 4.30; p<0.01), followed by patients prescribed antihypertensives thought less likely to induce diabetes (HR 2.32; 95% CI 1.74 to 3.09; p<0.01) and patients prescribed antihypertensives thought more likely to induce diabetes (HR 1.59; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.20; p<0.01) in the subsequent 6 years of follow-up, when compared to diclofenac.

Conclusions

These findings further support the link between statin use and new-onset diabetes and suggest that the understanding of diabetes risk associated with different antihypertensive drug classes may bear practice modification. This provides important information for future research, and for prescribers and patients when considering the risks and benefits of different types of cardiovascular risk-modifying drugs.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A national cohort study using electronic prescription database.

First longitudinal study to compare the incidence of subsequent diabetes between statins and antihypertensives with a control drug.

First study to measure outcome by proxy of first metformin prescription as indication of significant diabetes development.

Confounding factors such as BMI, family history and socioeconomic status are not controlled for in this electronic database analysis. However, there is no indication that these factors are unevenly distributed between the different ‘high risk’ study groups.

There is a small risk of misclassification for prescription of metformin for other conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome and extreme insulin resistance with acanthosis nigricans, but these are rare and are likely to only account for a small number of prescriptions.

Introduction

Statins are widely used and have established benefits in the prevention of cardiovascular events.1 However, recent studies suggested that statins may also increase the risk of new-onset diabetes,2–8 which in turn increases the risk of cardiovascular events. One meta-analysis reported the odds to be 9% (OR 1.09; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.17),5 with other studies showing the association with pravastatin and rosuvastatin use.3 4 7 9–11 More recent data indicate that the risk of new-onset diabetes with statin use could also be dose dependent, further supporting a causal link.6 Nevertheless, statins may still have an overall cardiovascular benefit.5

One of the difficulties in assessing the extent of this risk is that patients with higher cardiovascular risk prescribed statins also carry an increased baseline risk of developing diabetes because of similar risk factors.12–14 To understand the extent of the contributions of this increased baseline risk and the risk from the drugs themselves, we compared subsequent diabetes development in patients started on a statin with patients started on other drugs for cardiovascular risk management (antihypertensives) and patients at low baseline risk. We used a complete national prescribing data set15 to create a population-based cohort constructed of these three groups and compared the risk of subsequent development of clinically significant diabetes in each group.

Methods

Study design

Longitudinal cohort study using a national data set of de-identified routinely collected primary care electronic prescriptions of New Zealanders between ages 40 and 60 years, receiving first prescriptions of drugs studied (online supplementary appendix 1) in the year 2005.

Data source

Nationwide prescription data for the purpose of this study were sourced electronically from a complete national prescribing data set, the New Zealand Health Information Service’ (NZHIS) pharmaceutical collection.16 Community prescribing is electronic in primary care in New Zealand, making this information accessible via NZHIS. Individual patients are assigned a unique identifier (National Health Index (NHI) number) in the New Zealand health system and this is attached to their prescriptions, allowing this to be the main data key linkage tool. All NHIs were de-identified at the point of data extraction and automatically assigned a unique encrypted code.

Cohort construction

The cohort construction is illustrated in figure 1 (flow chart of cohort formation). The cohort included patients aged 40–60 years in the year 2005 without prior prescription of excluded drugs and metformin (outcome drug; online supplementary appendix 1), and all patients having received a prescription of at least one of the drugs of interest between 2005 and 2011. These drugs were statins, antihypertensives, diclofenac (comparator drug) or metformin (outcome drug). Diclofenac was chosen as the comparator drug to represent low diabetic risk patients presenting to primary care services with musculoskeletal injuries. Some antihypertensives are associated with subsequent development of diabetes. Thiazide diuretics (T) and β-blockers (BB) are most strongly associated with increased risk,14 17–19 whereas little association has been made with ACE inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) and calcium channel blockers (CCB).18 19 Following the literature, those in the antihypertensive drug group were further divided into ‘antihypertensives TB’ for antihypertensives thought likely to increase diabetes risk (T and BB) and ‘antihypertensives AAC’ for antihypertensives thought less likely to doso (ACEi, ARB and CCB). A total of 195 194 records listed at least one of the drugs in the drug groups under study: diclofenac, antihypertensives TB, antihypertensives AAC and statin groups. Patients belonging to two study groups concurrently in 2005 were then excluded. Data were further examined and cleaned to identify duplicate individuals, exclusion drugs and data entry error. This left 32 086 unique individuals to form the 2005 study cohort with 7140, 5769, 6565 and 12 612 in the diclofenac, antihypertensives TB, antihypertensives AAC and statin groups, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of cohort formation.

Exclusion

Patients who had a prescription for oral hypoglycaemics, insulin, oral corticosteroids (known to increase the risk of diabetes) or any of the study group medications of interest (online supplementary appendix 1) prior to 2005. The upper age limit was chosen to limit the inclusion of cardiovascular drugs prescribed for treatment of other cardiovascular conditions (eg, heart failure).

Exposure

New Zealand adults who received their first prescription of statins, antihypertensives or diclofenac in the calendar year 2005 without prior prescription of exclusion drugs and metformin.

Primary outcome measure

The proportion of patients receiving their first prescription of metformin in the calendar years 2006–2011. Metformin is the recommended first-line treatment for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus in New Zealand.20

Analysis

Patient baseline demographics were summarised using simple descriptive statistics and differences between cohorts were assessed using χ2 statistics calculated on OpenEpi online.21 Since these are routinely collected electronic records, loss to follow-up cannot be measured directly, and will be measured by proxy of medication persistence, death and emigration rate. Persistence with medications was determined as having at least one prescription a year, and persons-years were calculated based on these data. Death and emigration rates were calculated by direct age standardisation based on information available on Statistics New Zealand life tables to estimate loss to follow-up for our cohorts.22 Incidence rates and HRs with 95% CIs were calculated to compare the risk of new-onset diabetes between the diclofenac group and the other three cohorts. HRs were calculated in SPSS V.20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc) using the Cox proportional hazards regression model, and multivariable analysis was used to adjust for differences in the demographic structure of the cohorts. All analyses were two-sided.

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the cohorts are summarised in table 1 (Cohort demographic). The sex of the patients differed by groups with a higher proportion of females (68.8%, χ2(1)=447.86, p<0.001) in the antihypertensives TB group, and of males (66.6%, χ2(1)=545.35, p<0.001) in the statin group. The age of patients also differed across groups with patients receiving cardiovascular risk-modifying drugs tending to be older than those in the diclofenac group (χ2(1)=1016.39, p<0.001). New Zealand European was the major ethnicity in all study groups. There were more Maori in the diclofenac group with only a few in the statin group (χ2(1)=301.86, p<0.001). These differences between groups are adjusted for in the multivariable analysis.

Table 1.

Cohort demographic

| Overall | Diclofenac group | Antihypertensives TB group | Antihypertensives AAC group | Statins group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| Recruited number of patients | 100 (32 086) | 22.25 (7140) | 17.98 (5769) | 20.46 (6565) | 39.31 (12 612) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 52.98 (16 999) | 49.69 (3548) | 31.20 (1800) | 49.52 (3251) | 66.60 (8400) |

| Female | 47.01 (15 083) | 50.29 (3591) | 68.80 (3969) | 50.46 (3313) | 33.38 (4210) |

| Unknown | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Age | |||||

| 40–44 | 22.0 (7045) | 33.8 (2415) | 20.4 (1179) | 19.1 (1255) | 17.4 (2196) |

| 45–49 | 22.7 (7289) | 26.4 (1886) | 22.4 (1295) | 22.0 (1445) | 21.1 (2663) |

| 50–54 | 26.1 (8367) | 21.1 (1509) | 27.4 (1582) | 27.3 (1794) | 27.6 (3482) |

| 55–59 | 29.2 (9385) | 18.6 (1330) | 29.7 (1713) | 31.5 (2071) | 33.9 (4271) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| NZ European* | 69.46 (22 287) | 61.3 (4377) | 76.39 (4407) | 69.23 (4545) | 71.03 (8958) |

| Maori | 7.05 (2261) | 14.26 (1018) | 5.91 (341) | 7.75 (509) | 3.12 (393) |

| Pacific Island† | 3.48 (1116) | 8.75 (625) | 1.87 (108) | 2.83 (186) | 1.56 (197) |

| Asian‡ | 5.31 (1703) | 5.04 (360) | 5.23 (302) | 4.90 (322) | 5.70 (719) |

| Others§ | 0.93 (298) | 1.44 (103) | 0.81 (47) | 0.70 (46) | 0.81 (102) |

| Unknown¶ | 4421 | 657 | 564 | 957 | 2243 |

*NZ European=NZ European, Other European, European NFD.

†Pacific Island=Cook Island, Fijian, Niuean, Samoan, Tokelauan, Tongan, Pacific Island, Other Pacific Island.

‡Asian=Asian, Chinese, Other Asian, Indian, Southeast Asian.

§Others=African, Latin American/Hispanic, Middle Eastern, other, other ethnicity.

¶Unknown=other, other ethnicity, not stated, don't know, refused to answer, response unidentifiable.

AAC, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers; TB, thiazides and β-blockers.

Cohort characteristics and follow-up

A total of 32 086 unique patients were eligible for analysis from the recruitment: 7140 for the diclofenac group, 5769 for the antihypertentives TB group, 6565 for the antihypertensives AAC group and 12 612 for the statin group (figure 1). Persistence with index medications for each group was 38.4%, 71.3%, 70.9% and 76.1%, respectively (online supplementary appendix 2). The persistence within the control group was expectedly lower as diclofenac is not usually indicated for long-term use. Loss of follow-up due to deaths and emigration is estimated to be less than 2% of those who were not persistent with medications, assuming that the death and emigration rates were similar to those of the overall New Zealand population within similar age groups during the study period.

Primary analysis

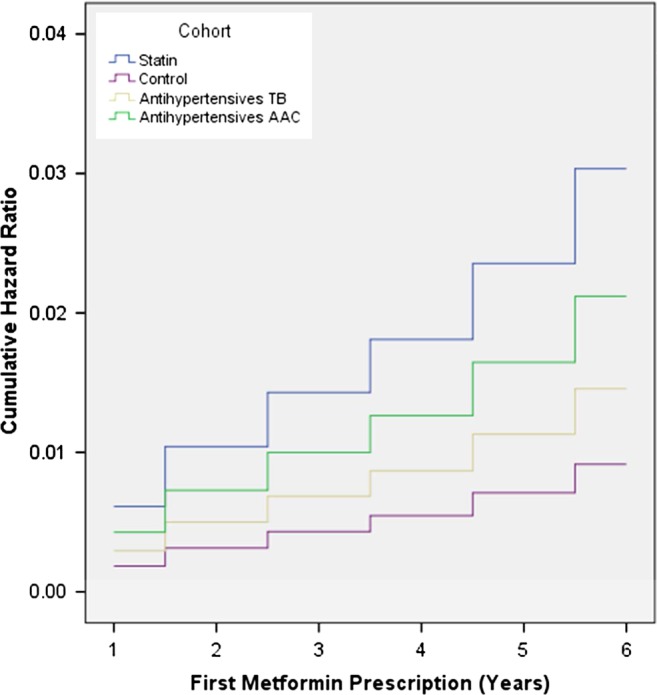

The primary outcome results indicated that between 2006 and 2011, 710 patients within the four groups received their first prescription of metformin. This represents 1.2%, 1.5%, 2.3% and 3.1% of those exposed to the diclofenac, antihypertensives TB, antihypertensives AAC and statin groups, respectively. The incidence rates were 2.5, 2.8, 4.2 and 5.5 cases per 1000 person-years for the first prescription of metformin (table 2) accordingly. In the multivariable analysis, patients started on statins had the highest risk of receiving a first prescription of metformin in 6 years after exposure compared to the control group (HR 3.31; 95% CI 2.56 to 4.30; p<0.01). In contrast to the existing research, when compared to patients on diclofenac, patients on the antihypertensives AAC group have a moderate risk of receiving their first prescription of metformin in 6 years (HR 2.32; 95% CI 1.74 to 3.09; p<0.01), and patients in the antihypertensives TB group have a slightly elevated risk (HR 1.59; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.20; p<0.01; table 3). Our analysis indicates a duration response. The HR of developing new-onset diabetes was approximately constant over the duration of the study as demonstrated by the plot for the cumulative HRs for the first metformin prescription in each study cohort (figure 2), adjusting for age, sex and ethnicity.

Table 2.

Incidence rate for first prescription of metformin

| Groups | Person-time | Number of new cases | Incidence rate cases per person-year | Incidence rate cases per 1000 person-years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diclofenac | 33 190 | 84 | 0.00253 | 2.5 |

| TB | 30 791 | 85 | 0.00276 | 2.8 |

| AAC | 35 383 | 150 | 0.00424 | 4.2 |

| Statin | 70 455 | 391 | 0.00555 | 5.5 |

AAC, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers; TB, thiazides and β-blockers.

Table 3.

Six-year risk of first prescription of metformin in study groups compared to control group

| Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis*,† |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Metformin (%) | HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Cohort | ||||||||

| Diclofenac | 7140 | 84 (1.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| TB | 5769 | 85 (1.5) | 1.25 | 0.93 to 1.70 | 0.142 | 1.59 | 1.15 to 2.20 | 0.005 |

| AAC | 6565 | 150 (2.3) | 1.95 | 1.50 to 2.55 | <0.0001 | 2.32 | 1.74 to 3.09 | <0.0001 |

| Statin | 12 612 | 391 (3.1) | 2.66 | 2.10 to 3.37 | <0.0001 | 3.31 | 2.56 to 4.30 | <0.0001 |

*Cox regression.

†Adjusting for: age, sex and ethnicity.

AAC, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers; TB, thiazides and β-blockers.

Figure 2 .

HR for first prescription of metformin in each year for different study groups.

Subgroup analyses

Patient demographics were analysed to assess other characteristics of recipients of first metformin prescription (see online supplementary appendix 3). Cox regression model analysis revealed that females had a lower risk than males (HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.00, p=0.05) and that there was no difference in risk between age groups within our cohort age range. However, risks were increased with all other ethnicities when compared to the New Zealand European ethnic group. The Pacific Island and Asian ethnic group had the highest risk at HR 3.57 (95% CI 2.63 to 4.85, p<0.01) and HR 3.72 (95% CI 3.00 to 4.62, p<0.01), respectively.

To assess whether those at risk of developing diabetes were prescribed higher doses of their prescribed medications, the drug doses of their first prescribed indexed medications in 2005 among those prescribed metformin were assessed. In the statin group, 96.9% of patients were prescribed 40 mg and less of simvastatin as well as atorvastatin. For patients in the antihypertensives TB group, 78.8% of patients were on BBs and 88% of those on thiazides were on 2.5 mg of bendrofluazide. This indicates that patients started on metformin were prescribed conservative doses of cardiovascular risk-modifying drugs.

There were 743 patients who swapped study cohorts during the study period. Of these, 220 were from the diclofenac group, 206 from the antihypertensives TB group, 166 from the antihypertensives AAC group and 151 from the statin group (online supplementary appendix 4). Excluding these patients in a per-protocol analysis had little effect on the HRs compared to the intention-to-treat analysis (results of analysis available but not included), which could indicate that the effect is rare or that the exposure is steady.

Discussion

Patients on any cardiovascular risk-modifying drugs had a higher risk of new-onset diabetes compared to patients receiving diclofenac. Patients receiving first prescription for statins were at the highest risk of subsequently developing clinically significant diabetes, with a risk three times that of those prescribed diclofenac. Patients prescribed ACEi, ARBs or CCB were the next highest risk, being twice as likely to receive a metformin prescription, while those prescribed thiazides and BBs were only at slightly increased risk.

The association between new-onset diabetes, as estimated by first metformin prescriptions, and initiation of statins found in this study is consistent with recent reports. However, the risk in this population was lower (3.1%) than the 9% risk reported in meta-analyses.23–25 Recent publications have identified the risks of new-onset diabetes with statin drug use ranging from 2.4% to 8.5%.23–26 In contrast to our study, the diagnosis of diabetes in these other studies were identified by indicators such as disease classification recording, or intermediate indicators such as laboratory investigations of glycated haemoglobin and fasting serum glucose readings. This will draw in milder levels of hyperglycaemia where lifestyle changes can still be the first line of management and where the laboratory threshold determines the disease rates. This study is the first to identify the incident rate of clinically significant diabetes as indicated by the first prescription of metformin in a non-research population. This is an outcome that matters to patients.

Our study is also the first to compare the risks of diabetes development in patients on statins against patients on other cardiovascular risk modifying drugs who might also be considered to be ‘high risk’. Patients initiated on antihypertensive drugs were, like those prescribed statins, at greater risk of developing diabetes compared to those on diclofenac. Our findings therefore allow an assessment of the comparative risks of new-onset diabetes in patients with an already higher risk on different classes of antihypertensives. There may be several explanations for the differences seen. First, it may be a true association. Second, patients already with risk factors for diabetes (such as obesity) are less likely to be prescribed medications that will further increase this risk.14 27 Hence, they are more likely to receive prescriptions of ACEi or ARBs for management of hypertension due to a lesser known risk of inducing diabetes. We also observed conservative dosing in patients on thiazides and BBs, which may attenuate the risk. Finally, higher baseline risk factors (dyslipidaemia and hypertension) that lead to prescription of the study drugs also increase the risk of subsequent glucose elevation, and this effect is observed in patients on as well as off statin use.28 Our study is not able to answer these questions, but raises these for future research.

Since all data collected are electronic records, patient persistence with medication can be grossly assessed. There were high rates of persistence with medications within the study groups, in particular for the antihypertensives and statins. Given that only a total of 743 patients (2.3% of the 2005 cohort) swapped into different study groups during the study period, these were relatively clean groups for analyses of risks.

The development of clinically significant diabetes was estimated using a proxy measure, utilising the first prescription of metformin. The validity of using routinely collected and electronically stored prescription data for diagnosing diabetes has been demonstrated previously.15 29 The use of routinely collected data also provides access to a complete national population-based cohort. We were able to assess this cohort longitudinally over a period of 6 years in a representative primary care population rather than a trial population with tightly constrained entry criteria.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The nature of the electronic data sets available means it is not possible to obtain other factors contributing to cardiovascular and diabetes risks to more precisely define subgroups and allow a direct comparison of the cohorts’ baseline levels of risk of developing diabetes (eg, body mass index and family history). These are major uncontrolled confounding and effect modifiers that cannot be accounted for in this study.

There is also the risk of misclassification. Metformin may also be prescribed for management of other conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome and extreme insulin resistance with acanthosis nigricans; however, this is likely to account for only a small proportion of prescriptions. With first prescription of metformin, we have also excluded patients who present infrequently to their primary healthcare providers for well-checks and routine follow-up (missing new-onset diabetes) and those who may have presented acutely with diabetic emergency (as they will be started on alternate hypoglycaemic agents).

It is also uncertain as to how frequently these patients are tested for diabetes mellitus in the primary care setting, as the electronic system is not currently linked to laboratory data. The study is also unable to control for the duration of mild hyperglycaemia prior to the start of metformin.

In this study, we have not distinguished between the various statin doses and formulations.

Conclusions

Patients initiating treatment with any of the index cardiovascular risk-modifying drugs have some risk of developing clinically significant new-onset diabetes compared to those prescribed diclofenac. However, patients prescribed statins have the highest risk of new-onset diabetes, strengthening the recent signal from current literature. Patients prescribed ACEi, ARBs and CCB were also at moderately increased risk, while patients prescribed thiazides and BBs only appeared to have a mildly increased risk. The effect seen carries an exposure and duration-response between groups, and is also seen in patients prescribed relatively low doses of these drugs, which is important information for prescribers. This provides additional information on the comparative safety of these drugs in a real-world setting in primary care, where the bulk of these prescriptions are likely to be initiated. This is useful information for doctors and patients considering the balance of harms against the potential for benefit of both statins and different cardiovascular risk-modifying medications in different populations.

Further research

Diabetes, as a diagnosis based on a measurement, is itself a source of morbidity and mortality largely as a risk factor for other disease, predominantly cardiovascular disease. Whether there is an additive risk of inducing diabetes with combinations of different cardiovascular risk-modifying drugs is currently unknown, and an important area for research to inform decision-making on prescribing, given the prevalence of multimorbidity and likely coprescription. This is a subject for further study. It is also unclear what effect this additional risk of diabetes will have on morbidity and mortality for patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Canterbury Chair of General Practice Trust (Inc) for sponsoring the role of the General Practice Research Registrar for this project. They would also like to thank the University of Otago, New Zealand for providing all computing software.

Footnotes

Contributors: OC, DM, BM-G and PB designed the study. BM-G ran the search for electronic prescription data according to the study protocol. OC designed the data collection tools, monitored the data collection for the whole study, wrote the statistical analysis plan, cleaned and analysed the data and drafted and revised the article. OC and JW analysed the data. OC, DM and JW revised the draft of the article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: As all data were de-identified by encryption; ethics approval was confirmed as not required by the National Ethics Advisory Committee, New Zealand as stated in the Ethical Guidelines for Observational Studies: Observational Research, Audits and Related Activities, NEAC, December 2006 (Upper South B Regional Ethics Committee, Ethics ref: URB/12/EXP/022).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code and data set available from the corresponding author at Dryad repository, who will provide a permanent, citable and open access home for the data set.

References

- 1.Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(1):CD004816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Culver AL, Ockene IS, Balasubramanian R, et al. Statin use and risk of diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women in the Women's Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:144–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberton M, Wu P, Druyts E, et al. Adverse events associated with individual statin treatments for cardiovascular disease: an indirect comparison meta-analysis. QJM 2012;105:145–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills EJ, Wu P, Chong G, et al. Efficacy and safety of statin treatment for cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis of 170,255 patients from 76 randomized trials. QJM 2011;104: 109–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preiss D, Sattar N. Statins and the risk of new-onset diabetes: a review of recent evidence. Curr Opin Lipidol 2011;22:460–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preiss D, Seshasai S, Welsh P, et al. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;305:2556–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray H, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet 2010;375:735–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridker P, Danielson E, Fonseca F, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated CRP. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh KK, Quon MJ, Han SH, et al. Differential metabolic effects of pravastatin and simvastatin in hypercholesterolemic patients. Atherosclerosis 2009;204:483–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh KK, Quon MJ, Han SH, et al. Atorvastatin causes insulin resistance and increases ambient glycemia in hypercholesterolemic patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1209–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaborators Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90 056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Movahed MR, Sattur S, Hashemzadeh M. Independent association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension over a period of 10 years in a large inpatient population. Clin Exp Hypertens 2010;32:198–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verdecchia P, Reboldi G, Angeli F, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of new diabetes in treated hypertensive subjects. Hypertension 2004;43:963–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dagenais GR Auger P, Bogaty P, et al. Increased occurrence of diabetes in people with ischemic cardiovascular disease and general and abdominal obesity. Can J Cardiol 2003;19:1387–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Unintended effects of statins in men and women in England and Wales: population based cohort study using QResearch database. BMJ 2010;49:340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Source: Ministry of Health, Pharmaceutical Collection.

- 17.Smith SM, Gong Y, Turner ST, et al. Blood pressure responses and metabolic effects of hydrochlorothiazide and atenolol. Am J Hypertens 2012;25:359–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mancia G, Grassi G, Zanchetti A. New-onset diabetes and antihypertensive drugs. J Hypertens 2006;24:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aksnes T, Reims H, Kjeldsen S, et al. Antihypertensive treatment and new onset diabetes mellitus. Curr Hypertens Rep 2005;7:298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.New Zealand Guidelines Group New Zealand primary care handbook 2012. 3rd edn Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dean AG SK, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 2.3.1. http://www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2011/23/06 (accessed 23 Oct 2012)

- 22.Statistics New Zealand. http://www.stats.govt.nz/infoshare.

- 23.Wang K-L, Liu C-J, Chao T-F, et al. Statins, risk of diabetes, and implications on outcomes in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1231–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rautio N, Jokelainen J, Oksa H. Do statins interfere with lifestyle intervention in the prevention of diabetes inprimary healthcare? One-year follow-up of the FIN-D2D project. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma T, Tien L, Fang C-L, et al. Statins and new-onset diabetes: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study. Clin Ther 2012;34:1977–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter AA, Gomes T, Camacho X, et al. Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population based study. BMJ 2013:346:f4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdullah A, Stoelwinder J, Shortreed S, et al. The duration of obesity and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:119–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golomb BA, Koperski S, White HL. Statins raise glucose preferentially among men who are older and at greater metabolic risk. Circulation 2012;125:A055 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu K. Diabetics can be identified in an electronic medical record using laboratory tests and prescriptions. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:431–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.