Abstract

Objectives

To identify anthracycline-induced acute (within 1 month) and early-onset chronic progressive (within 1 year) cardiotoxicity in children younger than 16 years of age with childhood malignancies at a tertiary care centre of Pakistan.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan.

Participants

110 children (aged 1 month–16 years).

Intervention

Anthracycline (doxorubicin and/or daunorubicin).

Outcome measurements

All children who received anthracycline as chemotherapy and three echocardiographic evaluations (baseline, 1 month and 1 year) between July 2010 and June 2012 were prospectively analysed for cardiac dysfunction. Statistical analysis including systolic and diastolic functions at baseline, 1 month and 1 year was carried out by repeated measures analysis of variance.

Results

Mean age was 74±44 months and 75 (68.2%) were males. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia was seen in 70 (64%) patients. Doxorubicin alone was used in 59 (54%) and combination therapy was used in 35 (32%). A cumulative dose of anthracycline <300 mg/m2 was used in 95 (86%). Fifteen (14%) children developed cardiac dysfunction within a month and 28 (25%) children within a year. Of these 10/15 (66.6%) and 12/28 (43%) had isolated diastolic dysfunction, respectively, while 5/15 (33.3%) and 16/28 (57%) had combined systolic and diastolic dysfunction. Seven (6.4%) patients expired due to severe cardiac dysfunction. Eight of 59 (13.5%) children showed dose-related cardiotoxicity (p=<0.001). Cardiotoxicity was also high when the combination of doxorubicin and daunorubicin was used (p=0.004).

Conclusions

Incidence of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity is high. Long-term follow-up is essential to diagnose its late manifestations.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Oncology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First prospective cohort study on Anthracycline induced cardiotoxicity from Pakistan.

Repeated measures analysis of variance (r-ANOVA) analysis applied at three different intervals to detect acute and early onset cardiotoxicity.

Single centre study. Poor follow-up was evident in our population.

Introduction

Anthracycline (doxorubicin, daunorubicin) are potent but cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic agents are essential for treating many childhood malignancies.1 Cardiotoxicity can be acute (within a month of initiation of therapy), early-onset chronic progressive (within a year after therapy) and late-onset chronic progressive (after a year of therapy).2–4 Cardiac involvement may be seen as systolic and/or diastolic dysfunction, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias and pericardial effusion (PE).1–3 Children with cardiac dysfunction may be asymptomatic or present with severe cardiac failure even with isolated diastolic dysfunction.5 6 Cardiac damage may begin with the first dose of anthracycline or appear at any dose as there is no guaranteed safe dose limit. However, a higher cumulative dosage and combination therapy with different anthracycline derivatives are important risk factors.7 8 Anthracycline-induced diastolic dysfunction precedes systolic impairment. Clinical trials data have shown that anthracycline cardiotoxicity is associated with the slowly progressive deterioration of cardiac function, which may continue for years after treatment cessation.9 10 Transthoracic echocardiography is an important sensitive and non-invasive tool for evaluation of left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic function.11–13

There is a dearth of literature reporting on acute and/or long-term cardiotoxic adverse effects associated with anthracycline use in childhood malignancies from Pakistan. The aim of this study was to identify cardiac dysfunction caused by the anthracycline and factors related to it.

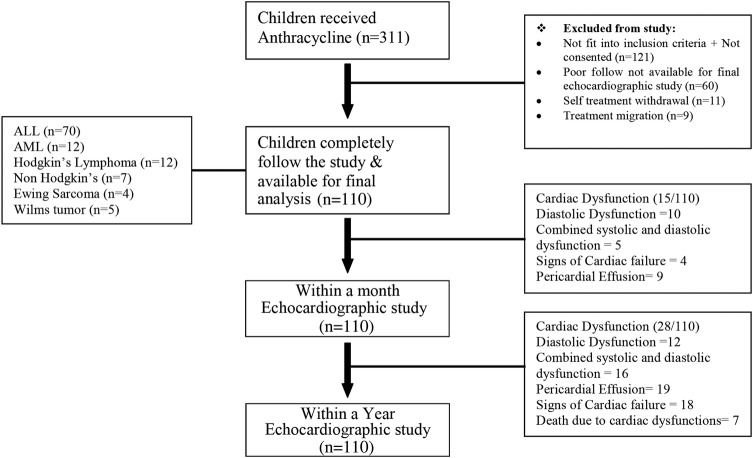

Patients and methods

This prospective cohort study was performed during July 2010–June 2012 at the Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan. It compared preanthracycline and postanthracycline echocardiographic evaluation in children aged 1 month–16 years with various childhood malignancies. Children with normal baseline echocardiography, who received anthracycline (daunorubicin and/or doxorubicin) as a part of their chemotherapy protocol and had the three desired echocardiographic evaluations (prechemotherapy 1-month and 1-year postchemotherapy), were enrolled in the study. Children were excluded; (1) if they were previously diagnosed with any structural heart disease or cardiomyopathy, (2) if they had succumbed to acute non-cardiac complications during their treatment course, (3) if they had a relapse of cancer. Of 190 patients enrolled in this study, 80 patients (42%) were excluded because of poor follow-up, treatment migration, self-treatment withdrawal. A total of 110 were available for final analysis (study flow diagram). Sociodemographic data were recorded and the type of cancer noted. A written informed consent (approved by the hospital's ethical board) was obtained from parent or guardian by the principle investigator at the time of enrolment in the study. Anthracycline use, adverse events and possible outcome was informed to the parents/guardians by the treating paediatric oncologist. Demographic details, type of malignancy, type and cumulative dose of anthracycline and complications were noted. Anthracycline cumulative dose with respect to body surface area was calculated as mg/m2. None of our patients received dexrazoxane during their management.

Echocardiographic analysis

GE vivid 7 Pro (General Electric Company, NYSE: GE, UK) or Philips IE33 (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, Massachusetts, USA) echocardiographic machines. Real-time images were obtained from standard parasternal, apical and subcostal projections. Transmitral inflow velocity pattern was recorded from the apical four-chamber view in accordance with the spectral Doppler techniques described elsewhere.11 M-mode tracings were taken from parasternal long axis view at the tips of mitral valve leaflets perpendicular to the LV endocardial surface and interventricular septum. Conscious sedation was used when indicated.

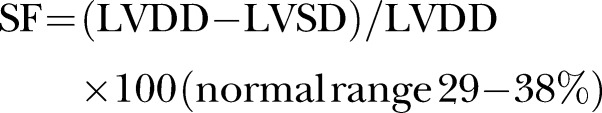

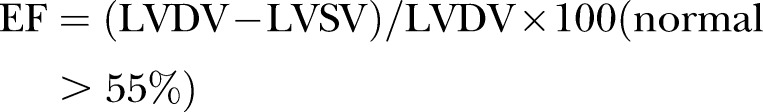

A baseline echocardiography was carried out in all patients as required in the management protocol. Echocardiographic assessment of systolic and diastolic LV function and PE was made. The mean of M-mode measurements from four cardiac cycles with the maximum diastolic diameters for each patient was used for analysis. LV cavity and posterior wall were measured in millimetre by the trailing edge-leading edge method. LV diastolic diameter and posterior wall diameter was measured at the point of maximum diastolic posterior deflection of the posterior wall. LV shortening fraction and ejection fraction were calculated by the formula

|

|

(SF, shortening fraction; EF, ejection fraction, LVDD, left ventricular diastolic diameter; LVSD, left ventricular systolic diameter; LVDV, left ventricular diastolic volume; LVSV, left ventricular systolic volume).

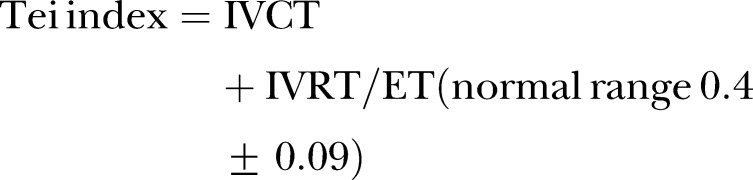

Transmitral inflow velocity in early diastole (E) and during atrial contraction (A) was measured and E/A ratio calculated. Pulsed Tissue Doppler Imaging was used to record the velocity of myocardium during the cardiac cycle. Peak early diastolic myocardial velocity (E′) was measured at the lateral corner of the mitral annulus to evaluate diastolic dysfunction, E/E′ ratio assesses diastolic dysfunction.14–16 Myocardial performance index (MPI or Tei index) that incorporates systolic and diastolic time intervals and expresses global ventricular function was calculated using Doppler tracings from mitral and aortic flows. Isovolumic contraction time (IVCT), ejection time (ET) and isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) were measured by standard techniques. In systolic dysfunction IVCT and IVRT will be prolonged while ET will be shortened, whereas in diastolic dysfunction IVRT will be prolonged.17 The higher the Tei index, the more abnormal would be the ventricular functions. Tei index was calculated as follows:

|

Echocardiographic evaluation for the acute and early-onset chronic cardiotoxicity was performed at three points in patient's treatment course: baseline, 1 month and 1 year after chemotherapy.

The length of follow-up was measured from the first exposure to anthracycline. Preanthracycline echocardiographic functions were compared with 1-month postanthracycline echocardiography for acute cardiotoxicity and with 1-year postanthracycline echocardiography for the early-onset cardiotoxicity. Additional echocardiographic assessments were performed in case of cardiac failure and managed accordingly.

Sample size

Sample size estimation was performed by using repeated measures analysis of variance (r-ANOVA) design at three different intervals. To detect a mean difference of 3–4% units18 in ejection fraction, with SD of 8 from baseline to 1 month (acute toxicity),19 using 90% power, with 95% CI and 5% level of significance a maximum of 100 children were needed to detect the anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Owing to an expected 10% dropout we inflate sample size to 110.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS software package (V.20.0, SPSS). Continuous variables (age, weight, height, body surface area, haemodynamic parameters, cumulative anthracycline dose and echocardiographic evaluation parameters) were presented in the form of mean and SD. Categorical variables (gender, type of childhood cancer, type of anthracycline and discharge disposition) were presented in frequency and percentages. Statistical analysis across systolic and diastolic dysfunction at baseline, 1 month and 1 year were made by r-ANOVA using SPSS. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Among the 110 children enrolled 75(68%) were males. Mean age was 74±44 months (median; 62 months). The demographic profile of the study population is shown in table 1. Haematological malignancies were predominant (n=82; 75%, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) in 70 and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) in 12). Five children had trisomy 21 (ALL in 3; AML in 2). Doxorubicin alone or in combination with daunorubicin was used in a majority of the children (n=94; 85%). Only 15 children received a high dose of anthracycline (cumulative dose >300 mg/m2). Follow-up echocardiography within 1 month revealed cardiac dysfunction in 15 (14%) children, while 28 (25%) developed myocardial dysfunction during their first year postanthracycline chemotherapy (figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic features of children who received anthracycline for their chemotherapy

| Total number of patients | n=110 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 74±44 months |

| Males | 75 (68) |

| Body surface area (BSA)* | 0.84±0.32 |

| Type of malignancy | |

| Haematological malignancies | |

| ALL | 70 (64) |

| AML | 12 (11) |

| Non-haematological malignancies | |

| Hodgkin+non-Hodgkin | 19 (17) |

| Miscellaneous (Ewing sarcoma=4; Wilms tumour=5) | 9 (8) |

| Type of anthracycline | |

| Doxorubicin | 59 (53) |

| Combine doxorubicin and daunorubicin | 35 (32) |

| Daunorubicin | 16 (15) |

| Cumulative anthracycline dose (mg/m2) | |

| <100 | 40 (36) |

| 100–300 | 55 (50) |

| >300 | 15 (14) |

| Received radiation | 24 (22) |

| Discharge disposition | |

| Died | 7 (6) |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram highlighting key features of study cohort.

Echocardiographic comparison of baseline myocardial function with that at 1 month and 1 year using r-ANOVA is shown in table 2. There was gradual and progressive deterioration in all myocardial functional parameters over time in children who received anthracycline. Children with haematological malignancies developed progressive cardiac dysfunction with time. Children with AML were found to have two times higher risk of developing myocardial dysfunction at 1 year compared with their baseline cardiac functions (table 3). Daunorubicin use was associated with the highest incidence of cardiac dysfunction at 1 year (10/16=63%) when compared with doxorubicin alone or in combination. High cumulative dose of doxorubicin, either alone or in combination with daunorubicin, had significant myocardial dysfunction (table 4).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic parameters comparing baseline readings with within a month and within a year after the start of anthracycline chemotherapy

| Echocardiographic parameters | Baseline readings | Within a month | Within a year | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF (%) | 69.9±4.3 | 67.3±5.3 | 62.6±9.6 | <0.001 |

| FS (%) | 36.6±2.6 | 35.3±2.8 | 32.9±5.0 | <0.001 |

| PWT (mm) | 6.7±1.3 | 5.8±1.1 | 5.4±1.1 | <0.001 |

| IVS (mm) | 5.9±0.2 | 5.4±1.1 | 4.9±1.0 | <0.001 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 34.5±5.6 | 35.8±5.4 | 37.3±5.8 | <0.001 |

| LVESD (mm) | 22.0±4.2 | 23.4±4.4 | 25.3±5.4 | <0.001 |

| E (cm/s) | 93.7±9.2 | 86.8±10.3 | 85.1±11.5 | <0.001 |

| A (cm/s) | 58.9±6.5 | 63.5±7.5 | 64.6±9.1 | <0.001 |

| E/A ratio | 1.6±1.8 | 1.38±0.21 | 1.3±.33 | <0.001 |

| E′ (cm/s) | 14.1±2.4 | 12.2±2.3 | 11.1±2.5 | <0.001 |

| E/E′ ratio | 6.7±1.05 | 7.17±1.1 | 8.1±2.6 | <0.001 |

| Tei index (MPI) | 0.3±.05 | 0.4±.05 | 0.4±.07 | <0.001 |

| DT | 164.3±15.3 | 171.6±19.8 | 174.7±28.9 | <0.001 |

A, peak flow velocity during atrial contraction; DT, E deceleration time; E, early diastolic mitral peak flow velocity; E′, peak early diastolic myocardial velocity; EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractioning shortening; IVS, interventricular wall thickness; LVEDD, left ventricular (LV) end diastolic diameter; LVESD in mm, LV end systolic diameter; LVESD, LV end systolic diameter; PWT, LV posterior wall thickness; Tei index, MPI=Myocardial performance index.

Table 3.

Relationship of anthracycline and cardiac dysfunction according to the type of malignancy

| Malignancy | Cardiac dysfunction |

p Value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within a month n (%) |

Within a year n (%) |

|||

| ALL (n=70) | 3 (4) | 12 (17) | 0.004 | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.8) |

| AML (n=12) | 5 (42) | 9 (75) | 0.091 | 2.3 (1.1 to 4.7) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma (n=12) | 3 (25) | 2 (17) | 0.045 | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.6) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=7) | 2 (28) | 2 (28) | 1.000 | 4.0 (0.1 to 136.9) |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia.

Table 4.

Types of anthracycline used alone or in combination and their relation to cardiac dysfunction

| Anthracycline | Anthracycline cumulative dosage |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysfunction n (mg/m2, mean±SD) |

No dysfunction n (mg/m2, mean±SD) |

||

| Doxorubicin (n=59) | |||

| Within a month | 8 (276±199) | 51 (107±73) | <0.001 |

| Within a year | 9 (279±185) | 50 (104±69) | <0.001 |

| Daunorubicin (n=16) | |||

| Within a month | 5 (315±114) | 11 (273±93) | 0.440 |

| Within a year | 10 (310±85) | 6 (247±114) | 0.224 |

| Combination (n=35) | |||

| Within a month | 2 (297±123) | 33 (158±69) | 0.011 |

| Within a year | 9 (228±81) | 26 (144±64) | 0.004 |

Discussion

Anthracycline use in childhood malignancies has remarkably improved survival rates, increasing from 30% in the 1960 to 70% in the present era.20 It is the key component in many treatment strategies, but its cardiotoxicity remains as an important concern. Incidence of anthracycline-induced acute cardiotoxicity ranges between 3% and 21%, while late cardiotoxic effects vary between 0% and 57%.21 22 Anthracycline-induced acute cardiotoxicity in our study was 14%, which is a little high compared with the data published earlier.3 23 Generally, cumulative doses greater than 300–400 mg/m2 are associated with the greatest risk for cardiac injury. In our study, children receiving a cumulative dose >300 mg/m2 had shown significant toxicity.

Anthracycline causes LV enlargement, both systolic and diastolic diameters increase, resulting in decreased fractioning shortening (FS) and EF. In our study baseline FS changed significantly after anthracyclines (p=<0.001), which was similar to results published in the past.22 In our study a baseline LVEF of 69±4% reduced to 62.6±9.6% (p<0.001) at 1 year after completion of anthracycline therapy. Anthracycline-induced cardiac damage leads to deceased interventricular septal (IVS) and LV posterior wall thickness (PWT), thereby increasing after load and causing myocardial dysfunction.24 We also found differences in PWT and IVS preanthracycline and postanthracycline (p=<0.001).

Systolic and diastolic myocardial velocities correlate well with systolic and diastolic ventricular functions.25 26 E, A and E′ velocities, E/A and E/E′ ratios, deceleration time (DT) and MPI (Tei index) are good indicators of diastolic dysfunction.14–16 Changes in EF occurs later in the treatment course. The Tei index is more sensitive as compared with EF and FS as it correlates well with invasive measurements and has been validated in the assessment of ventricular function, with higher values suggesting poor prognosis. It can diagnose myocardial dysfunction in children even after a low dose of anthracyclines.27 In our study, within a year after completion of therapy, there was a statically significant change in diastolic parameters like E velocity (p=<0.001), A velocity (p=<0.001), E/A ratio (p=<0.001), E′ velocity (p=<0.001) and E/E′ ratio (p=<0.001). The Tei index and DT also showed significant changes (p=<0.001). These findings were consistent with the medical literature.28 29 Diastolic dysfunction has been reported to predict future systolic dysfunction,30 and the same was observed in our study as well. Of 15 children who developed cardiac dysfunction within a month, 10 (66.6%) had isolated diastolic dysfunction, while at their 1-year follow-up most of them had combined systolic and diastolic dysfunction (16/28, 57%).

Long-term follow-up studies have demonstrated cardiotoxicity in up to 70% of children treated with anthracycline.31 Younger patients are particularly susceptible to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Incidence of cardiac dysfunction found more in males and those younger than 5 years in our study. Godoy et al,32 also found that children younger than 4 years developed more cardiotoxicity (p<0.01) in their study population.

Dysfunction is also related to the type of anthracycline used. Both doxorubicin and daunorubicin are cardiotoxic but doxorubicin is more cardiotoxic.33 Doxorubicin was used in 59/110 of our patients and 8/59 (13.5%) children showed cardiac dysfunction in the acute phase. Their cumulative dose of doxorubicin was significantly higher as compared with those without dysfunction, 279.4±184±.9 vs 103.6±69.4 mg/m2 (p=<0.001). Cardiotoxicity was also high when a combination of doxorubicin and daunorubicin was used (p=0.004). In our study daunorubicin showed more toxicity in the early-onset chronic progressive phase.

PE can develop as a complication of anthracycline or radiation therapy, it may or may not be associated with cardiac dysfunction. It can be an early and alarming sign of cardiotoxicity suggestive of pericardial disease and sometimes leads to haemodynamic instability.34 Nineteen patients developed PE in this study.

Long-term cardiac follow-up is essential for early detection of cardiotoxicity because no dose of anthracycline is safe in children.8 9 Cardiotoxicity may progress years after discontinuation of therapy. Thirty years after anthracycline treatment, survivors have 15 times more chance of developing cardiac dysfunction than the general population and mortality from cardiac causes is eight times more.35 In our study, approximately 14% developed dysfunction within a month that increased to 25% at 1 year after completion of therapy. The full extent of the problem has yet to be addressed in many asymptomatic patients after the completion of treatment, emphasising the need for long-term follow-up.

In Pakistan multiple factors were related; non-compliance in follow-up with cardiologist and oncologist (in our study cardiac follow-up was seen in 58%). Common factors found were, parents understanding about disease, their educational status, financial constraints, minimal government and non-government agencies involvement and funding, remote area of residence far from treatment centres, paucity of treatment centres, poor counselling regarding long-term follow-up, lack of awareness among general practitioners regarding acute and chronic cardiac complications. This emphasises the need for long–term cardiac follow-up for better survival even in the asymptomatic patients.

A limitation of this study was that it involved a single centre. Owing to the lack of availability none of our children received cardioprotective agents such as dexrazoxane. Poor follow-up was evident in our study population which led to the exclusion of 80 patients. There was a high dropout rate; that is due to multiple factors aforementioned and also in study flow diagram.

Conclusion

The incidence of anthracycline-induced cardiac dysfunction is high. Risk factors include high cumulative dose, doxorubicin alone or in combination with daunorubicin. Regardless of the dose used, children treated with anthracycline require a long-term follow-up to detect late cardiotoxicity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Maha dev and Mr Cyrus Tariq for their help in data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: MAA acted as guarantor and senior investigator and reviewed the manuscript, observed every step and reviewed the ECHO data. ASS is the principal investigator, who generated the central idea, conducted the study and wrote the paper. AFS helped in conducting the study, study analysis and manuscript writing and reviewed the paper. SSM and MMA helped in data collection and helped in data entry and paper writing.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: AFS received research training support from the National Institute of Health's Fogarty International Center (1 D43 TW007585-01).

Ethics approval: Ethical Reivew Committee Aga Khan University (ERC # 2128 Ped ERC).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed by emailing to MAA: mehnaz.atiq@aku.edu.

References

- 1.Singal PK, Iliskovic N. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1998;339:900–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipshultz SE, Alvarez JA, Scully RE. Anthracycline associated cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood cancer. Heart 2008;94:525–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monsuez JJ, Charniot JC, Vignat N, et al. Cardiac side-effects of cancer chemotherapy. Int J Cardiol 2010;144:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shan K, Lincoff AM, Young JB. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bu'Lock FA, Mott MG, Oakhill A, et al. Left ventricular diastolic function after anthracycline chemotherapy in childhood: relation with systolic function, symptoms, and pathophysiology. Br Heart J 1995;73:340–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuppinger C, Timolati F, Suter TM. Pathophysiology and diagnosis of cancer drug induced cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2007;7:61–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giantris A, Abdurrahman L, Hinkle A, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children and young adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 1998;27:53–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kremer LC, van Dalen EC, Offringa M, et al. Frequency and risk factors of anthracycline-induced clinical heart failure in children: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 2002;13:503–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keizer HG, Pinedo HM, Schuurhuis GJ, et al. Doxorubicin (adriamycin): a critical review of free radical-dependent mechanisms of cytotoxicity. Pharmacol Ther 1990;47:219–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers C. The role of iron in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Semin Oncol 1998;25:10–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bu'Lock FA, Mott MG, Martin RP. Left ventricular diastolic function in children measured by Doppler echocardiography: normal values and relation with growth. Br Heart J 1995;73:334–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganame J, Claus P, Uyttebroeck A, et al. Myocardial dysfunction late after low-dose anthracycline treatment in asymptomatic pediatric patients. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2007;20:1351–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinherz LJ, Graham T, Hurwitz R, et al. Guidelines for cardiac monitoring of children during and after anthracycline therapy: report of the Cardiology Committee of the Children Cancer Study Group. Pediatrics 1992;89:942–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagueh SF, Middleton KJ, Kopelen HA, et al. Doppler tissue imaging: a noninvasive technique for evaluation of left ventricular relaxation and estimation of filling pressures. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:1527–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, et al. Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparative simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study. Circulation 2000;102:1788–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohn DW, Chai IH, Lee DJ, et al. Assessment of mitral annulus velocity by Doppler tissue imaging in the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:474–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tei C, Ling LH, Hodge DO, et al. New index of combined systolic and diastolic myocardial performance: a simple and reproducible measure of cardiac function—a study in normal and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol 1995;26:357–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nousiainen T, Jantunen E, Vanninen E, et al. Early decline in left ventricular ejection fraction predicts doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in lymphoma patients. Br J Cancer 2002;86:1697–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tassan-Mangina S, Codorean D, Metivier M, et al. Tissue Doppler imaging and conventional echocardiography after anthracycline treatment in adults: early and late alterations of left ventricular function during a prospective study. Eur J Echocardiogr 2006;7:141–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Coleman MP, et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe and the United States. Cancer 2002;95: 1767–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, et al. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med 1979;91:710–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Sallan SE, et al. Chronic progressive cardiac dysfunction years after doxorubicin therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2629–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wojnowski L, Kulle B, Schirmer M, et al. NAD(P)H oxidase and multidrug resistance protein genetic polymorphisms are associated with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation 2005;112:3754–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iarussi D, Galderisi M, Ratti G, et al. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function after anthracycline chemotherapy in childhood. Clin Cardiol 2001;24:663–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erdogan D, Yucel H, Alanoglu EG, et al. Can comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation provide an advantage to predict anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy? Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 2011;39:646–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalay N, Basar E, Ozdogru I, et al. Protective effects of carvedilol against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:2258–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belham M, Kruger A, Mepham S, et al. Monitoring left ventricular function in adults receiving anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. Eur J Heart Fail 2007;9:409–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roodpeyma S, Moussavi F, Kamali Z. Late cardiotoxic effects of anthracycline chemotherapy in childhood malignancies. J Pak Med Assoc 2008;58:683–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velensek V, Mazic U, Krzisnik C, et al. Cardiac damage after treatment of childhood cancer: a long-term follow-up. BMC Cancer 2008;8:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoddard MF, Seeger J, Liddell NE, et al. Prolongation of isovolumetric relaxation time as assessed by Doppler echocardiography predicts doxorubicin-induced systolic dysfunction in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:62–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barry E, Alvarez JA, Scully RE, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: course, pathophysiology, prevention and management. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2007;8:1039–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godoy LY, Fukushige J, Igarashi H, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children with malignancies. Acta Paediatr Jpn 1997;39:188–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gharib MI, Burnett AK. Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: current practice and prospects of prophylaxis. Eur J Heart Fail 2002;4:235–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galderisi M, Marra F, Esposito R, et al. Cancer therapy and cardiotoxicity: the need of serial Doppler echocardiography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2007;5:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipshultz SE, Landy DC, Lopez-Mitnik G, et al. Cardiovascular status of childhood cancer survivors exposed and unexposed to cardiotoxic therapy. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1050–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.