Abstract

Objectives

To determine the sex-specific and age-specific risk ratios for the first-ever and recurrent hospitalisation for cerebrovascular, coronary and peripheral arterial disease in persons with other vascular history versus without other vascular history in Western Australia from 2005to 2007.

Design

Cross-sectional linkage study.

Setting

Hospitalised population in a representative Australian State.

Participants

All persons aged 34–85 years between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2007 were hospitalised with a principal diagnosis of atherothrombosis.

Data sources

Person-linked file of statutory-collected administrative morbidity and mortality records.

Main outcome measures

Sex-specific and age-specific risk ratios for the first-ever and recurrent hospitalisations for symptomatic atherothrombosis of the brain, coronary and periphery using a 15-year look-back period lead to the determining of prior events.

Results

Over 3 years, 40 877 (66% men; 55% first-ever) were hospitalised for atherothrombosis. For each arterial territory, age-specific recurrent rates were higher than the corresponding first-ever rates, with the biggest difference seen in the youngest age groups. For all types of first-ever atherothrombosis, the rates were higher in those with other vascular history and the risk ratios declined with an advancing age (trend: all p<0.0001) and remained significantly >1 even for 75–84 years old. However, for recurrent events, the rates were marginally higher in those with other vascular history and no risk ratio age trend was apparent with several not significantly >1 (trend: all p>0.13).

Conclusions

This study of hospitalised atherothrombosis suggests first-events predominate and that the risk of further events in the same or other arterial territory is very high for all ages and both sexes, accentuating the necessity for an early and sustained active prevention.

Keywords: VASCULAR MEDICINE, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Quantification of a new and recurrent vascular risk by disease subtype and history.

Excluding the very elderly, non-hospitalised events and underdiagnoses of other vascular disease likely overestimated the dominance of the coronary events.

Including non-acute hospitalisations will have increased the absolute event rates but had negligible effect on relative comparisons.

Introduction

Only few studies have reported the population-based estimates of the rate and determinants of incident and recurrent vascular events of the brain (cerebrovascular disease), coronary (coronary heart disease) and periphery (peripheral arterial disease) collectively. The Oxford Vascular Study1 indicated that 63% of all atherothrombosis subtypes were incident (first-ever) events, and 37% were recurrent. Cerebrovascular events were most common, more than coronary, and all rates rose steeply with the age. In contrast, the international REACH Registry2 of atherothrombotic disease in primary-care suggested that the coronary events were most common, and that the history of symptomatic atheroma in more than one vascular bed was a strong predictor of higher rates of recurrence in the same and other vascular beds.

We aimed to explore the application of the results from the OXVASC and REACH studies1 2 in a population-based study of hospitalisations for vascular disease among Western Australians (WA) aged 35–84 years between 2005 and 2007. Our specific aims were to determine: (1) the absolute age-specific and sex-specific annual rates of the first-ever and recurrent hospitalisations for symptomatic atherothrombosis of the brain, coronary and periphery; (2) the independent, significant contributions of atherothrombosis in a different vascular bed to the first-ever and recurrent hospitalisations for symptomatic events of the brain, coronary and periphery.

Methods

Setting and data source

We conducted a cross-sectional data linkage study of statutory-collected administrative data with no direct participant contact. The demographic profile and main health indices for WA are reflective of the Australian population.3 Linked public and private hospital morbidity and mortality data were extracted retrospectively from the WA Data Linkage System which is regularly audited for quality.4 Person-based records are linked with >99% accuracy using probabilistic matching on standard criteria.4 A linked file of all hospital admissions and deaths for all persons experiencing a cardiovascular event from 1 January 1990 to 31 December 2007 was available. As the morbidity data in the very elderly are considered as less reliable, event rates are calculated and reported for people aged 35–84 years. Atherothrombosis diagnoses were made from the discharge records according to the International Classification of Disease (ICD) versions 9-Clinical Modification and 10-Australian Modification.5

Definition and classification of atherothrombosis categories

Emergency and elective hospital admissions for brain, coronary and periphery ischaemia were identified from principal diagnoses on the discharge records, and are described elsewhere.6 Briefly, the coronary included myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stable angina or other ischaemic heart disease; the brain included cerebral infarction, transient ischaemic attack, precerebral or cerebral artery disease without infarction, unspecified stroke or intracerebral haemorrhage; and the periphery comprised atherosclerosis of the aorta, renal arteries or arteries of the extremities, unspecified peripheral vascular disease, Buergers disease or stricture of arteries. Hospital morbidity codes for brain,7 coronary8 and periphery9 ischaemia have been previously validated, as have vascular deaths.10 Hospital transfers were counted as one admission, as were readmissions for the same condition within 28 days for coronary, and within 1 day for each of the brain and periphery episodes.

All atherothrombosis hospitalisations between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2007 were classified based on the vascular bed (or disease subtype), and as first-ever or recurrent (or event type). The first-ever events were defined as having no hospitalisation in the same vascular bed during a 15-year look-back period, otherwise the event was classified as recurrent. The same 15-year look-back period was used to determine the binary variable of prior hospitalisation for other vascular manifestations. The 15-year look-back period was also used to identify the comorbidities of diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, chronic lung disease and cancer. There were <0.001% missing values for any of the variables used in this study.

Statistical analysis

Men and women were analysed separately. For each disease subtype, selected differences in the patient characteristics (age by event type, and the first-ever events by other vascular history) were evaluated using t tests and χ2, respectively. The overall proportions of the first-ever and recurrent disease patients with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, chronic lung disease and cancer were calculated. Age-specific first-ever and recurrent rates were calculated for each of the brain, coronary and periphery stratified by other vascular history, using the number of events for that disease subtype over the 3 years (2005–2007) as the numerator and the corresponding disease-free (prevalent cases excluded) or disease-specific WA population as the denominator. Poisson regression was used to estimate the risk ratios for the first-ever and recurrent hospitalisations for each vascular bed for people with other vascular history compared with people without other vascular history. Models include sex, 5-year age group and other vascular disease history. An interaction term of other vascular disease by 10-year age group was added to the Poisson model to test for trend in the risk ratio across age groups. While technically we have estimated the rate ratios these are interpreted as 1-year risk ratios as these two ratios are numerically very similar when the rates have small magnitude. Data analyses were performed using SAS (V.9.3),11 and the statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

There were 27 156 hospitalisations (53% first-ever) for atherothrombosis in men and 13 721 (59% first-ever) in women aged 35–84 years between 2005 and 2007 (table 1). Seventy-six per cent of the brain admissions were first-ever, whereas just over half were first-ever for the coronary and periphery admissions. The coronary patients were younger for first-ever and recurrent admissions compared with their brain and periphery counterparts. The percentage of cases in the 75–84 year age group varied from a low of 17% in men for the first-ever coronary event, to a high of 56% in women with recurrent brain events. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity followed by diabetes and chronic kidney disease. The periphery patients were less likely to be admitted acutely and more likely to undergo angiography and/or invasive intervention than the brain or coronary patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of atherothrombosis hospitalisations* 2005–2007, Western Australia

| Disease subtype Cells in %, unless otherwise specified |

Men |

Women |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-ever | Recurrent | First-ever | Recurrent | |

| Coronary event, n=29 048 (row %) | 9682 (33) | 10 105 (35) | 4970 (17) | 4291 (15) |

| Mean age†, (SD) years | 62.2 (11.4) | 66.3 (10.8) | 66.0 (11.8) | 69.7 (10.7) |

| Patients aged 75–84/35–54 years | 17.2/26.0 | 26.9/15.5 | 29.2/18.9 | 40.9/10.7 |

| Prior cerebrovascular disease | 3.4 | 7.9 | 3.8 | 8.3 |

| Prior peripheral arterial disease | 1.9 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 4.2 |

| Diabetes | 20.7 | 33.7 | 23.9 | 39.7 |

| Hypertension | 50.7 | 78.1 | 59.9 | 85.4 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7.7 | 18.5 | 9.3 | 20.8 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 11.1 | 22.1 | 12.2 | 21.3 |

| Heart failure | 8.9 | 20.7 | 12.3 | 27.1 |

| Chronic lung disease | 5.2 | 13.4 | 8.2 | 19.7 |

| Cancer | 8.2 | 13.9 | 9.9 | 17.5 |

| Acute admission* | 51.2 | 36.9 | 52.1 | 42.7 |

| Brain event, n=7862 (row %) | 3556 (45) | 1149 (15) | 2465 (31) | 692 (9) |

| Mean age†, (SD) years | 68.3 (11.0) | 71.2 (9.9) | 70.6 (11.6) | 72.7 (10.7) |

| Patients aged 75–84/35–54 years | 36.1/12.9 | 47.2/8.0 | 48.7/12.2 | 56.1/7.5 |

| Prior coronary heart disease | 20.6 | 27.0 | 15.0‡ | 22.4 |

| Prior peripheral arterial disease | 2.2 | 5.1 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| Diabetes | 26.9 | 33.9 | 26.0 | 33.1 |

| Hypertension | 65.9 | 81.3 | 66.9 | 81.8 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12.1 | 17.8 | 11.5 | 21.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 20.3 | 26.0 | 21.3 | 33.5 |

| Heart failure | 9.8 | 14.5 | 12.0 | 21.0 |

| Chronic lung disease | 8.3 | 14.5 | 10.2 | 15.3 |

| Cancer | 14.6 | 18.5 | 14.3 | 18.4 |

| Acute admission* | 73.8 | 60.8 | 76.5 | 70.5 |

| Periphery event, n=3967 (row %) | 1276 (32) | 1388 (35) | 680 (17) | 623 (16) |

| Mean age†, (SD) years | 69.3 (10.1) | 70.5 (9.6) | 71.2 (11.0) | 72.7 (10.0) |

| Patients aged 75–84/35–54 years | 36.9/8.9 | 40.3/6.4 | 48.5/10.3 | 54.6/7.2 |

| Prior coronary heart disease | 27.5 | 30.4 | 18.1‡ | 24.4 |

| Prior cerebrovascular disease | 6.4 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 8.0 |

| Diabetes | 11.5 | 8.6 | 11.5 | 7.5 |

| Hypertension | 47.7 | 56.8 | 52.5 | 64.0 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14.4 | 16.7 | 12.8 | 14.3 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16.3 | 14.7 | 14.7 | 17.5 |

| Heart failure | 13.2 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 17.2 |

| Chronic lung disease | 11.4 | 16.4 | 11.3 | 14.4 |

| Cancer | 12.6 | 16.4 | 11.6 | 14.1 |

| Acute admission* | 12.2 | 13.0 | 14.6 | 11.4 |

| All vascular events, n (40 877) (row-%) | 14 514(35) | 12 642(31) | 8115 (20) | 5606 (14) |

*For coronary disease, cerebral infarction or transient ischaemic attack or atherosclerosis of the periphery.

†For each disease subtype, mean age varied by sex and event type (incident vs recurrent) (All p<0.0001).

‡For the first-ever brain and periphery events, proportions with prior coronary disease varied by sex (both p<0.0001).

The coronary admissions dominated the first-ever (67% in men and 61% in women) and recurrent hospitalisations (80% in men and 77% in women) for atherothrombosis (table 1). Only 6% of the first-ever coronary events in men and women had a prior admission for other vascular disease, compared with the first-ever brain hospitalisations (27% men, 18% women) and first-ever periphery (44% men, 30% women) hospitalisations. Recurrent events were more likely than the first-ever events to have a history of vascular disease in another vascular bed.

Atherothrombosis event rates and risk ratios

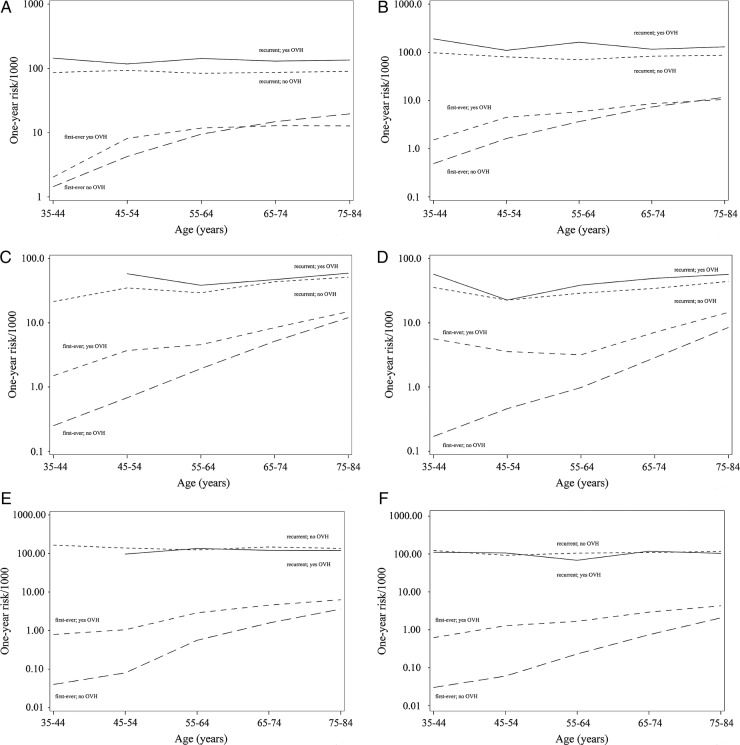

figure 1 shows the sex-specific and age-specific first-ever and recurrent hospitalisation rates for each disease subtype by history of other vascular disease. The age-specific rates ranged from about 3/1000 for the first-ever brain event with no other vascular history to about 200/1000 for recurrent coronary event with other vascular history. For each vascular bed, age-specific recurrent rates in those with and without other vascular history were higher than the first-ever rates, with the biggest difference seen in the youngest age groups. For the first-ever atherothrombosis, rates were generally higher in those with other vascular history compared with no other vascular history, particularly in the youngest age groups. There was a little difference between those with and without other vascular history for recurrent rates, a trend seen across all age groups, although there were no recurrent hospitalisations for the brain or periphery ischaemia involving another vascular territory in the 35–44 year age group in men.

Figure 1.

(A–F) Age-specific rates for hospitalised coronary, brain and periphery ischaemia by other vascular history (OVH; yes/no) in men (A, C and E) and in women (B, D and F).

Table 2 shows the sex-specific and age-specific risk ratios for the first-ever and recurrent hospitalisation by disease subtype comparing persons with other vascular history to those without. The highest risk ratios were for the first-ever brain hospitalisations in women 35–44 years (risk ratios 31.5, 95% CI 13.7 to 72.5) and for the first-ever periphery event in men and women 35–44 years (risk ratios 21.7, 95% CI 6.3 to 75.1; risk ratios 19.2, 95% CI 2.5 to 145.9, respectively), although CIs were wide. The risk of a first-ever event was greater for those with vascular history versus those without other vascular history in all age groups; however, the risk ratios for all first-ever disease subtypes declined with an advancing age (trend: all p<0.0001). Risk ratios for recurrent hospitalisations were smaller than for the first-ever hospitalisations and several others (including all risk ratios for recurrent periphery event) were not significant. Furthermore, risk ratios for recurrent hospitalisations showed no trend with an advancing age (trend: all p>0.05).

Table 2.

Hospitalised atherothrombotic disease 1-year risk ratios by sex and age group comparing persons with other vascular history to those without: Western Australia 2005–2007

| Age group years | Hospitalised disease 1-year risk ratio (95% CIs) |

Age group trend p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75–84 | ||

| Men | ||||||

| Coronary event | ||||||

| First-ever | 2.5 (0.8 to 7.9) | 3.5 (2.5 to 4.9) | 2.3 (1.9 to 2.8) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.9) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Recurrent | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.3) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.7) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.7) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 0.6283 |

| Brain event | ||||||

| First-ever | 5.4 (2.2 to 13.3) | 5.0 (3.7 to 6.7) | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.7) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Recurrent | –* | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.9) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 0.4721 |

| Periphery event | ||||||

| First-ever | 21.7 (6.3 to 75.1) | 5.1 (3.0 to 8.8) | 4.9 (3.8 to 6.3) | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.4) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.1) | <0.0001 |

| Recurrent | –* | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.9696 |

| Women | ||||||

| Coronary event | ||||||

| First-ever | 5.6 (1.4 to 22.5) | 5.3 (3.0 to 9.1) | 3.0 (2.1 to 4.3) | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.8) | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) | <0.0001 |

| Recurrent | 1.9 (0.9 to 4.1) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.1) | 2.3 (1.8 to 2.9) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 0.1357 |

| Brain event | ||||||

| First-ever | 31.5 (13.7 to 72.5) | 7.4 (4.4 to 12.3) | 3.0 (2.1 to 4.4) | 2.4 (1.9 to 2.9) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Recurrent | 1.9 (0.4 to 8.0) | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.3) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.0) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 0.8530 |

| Periphery event | ||||||

| First-ever | 19.2 (2.5 to 145.9) | 11.1 (5.0 to 24.7) | 6.7 (4.1 to 11.1) | 3.7 (2.7 to 5.1) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Recurrent | 1.7 (0.2 to 13.7) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.4) | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 0.8577 |

*No events in these age groups.

Discussion

This nationally representative population study of 40 877 first-ever and recurrent hospitalised atherothrombosis documents the sex-specific and age-specific risk ratios by vascular bed and history of other vascular disease. The majority of hospitalisations are first-ever, led by the coronary, then by the brain and least being the periphery, while the first-ever rates without a history of other vascular disease rose steeply with the age. Recurrent hospitalisation rates in men and women for any disease subtype are substantially higher than the corresponding first-ever rates, although narrowed with an advancing age. A history of other vascular disease was associated with a high risk of a new event in another vascular bed in younger men and women. In contrast, a history of other vascular disease had little influence on recurrent events of any type and at any age. Greater sex-specific and age-specific risk ratios occurred in the first-ever brain and periphery hospitalisations compared with the coronary events. There was a less variance in risk ratios for recurrent events across disease subtypes. These findings suggest that once atherothrombosis is clinically manifest in any vascular bed, the risk of further events in the same or another vascular location is very high for all ages and both sexes. This reinforces the need for an active secondary prevention in all patients with atherothrombotic disease of any type regardless of age.

Strengths and limitations

Extensive and high-quality person-based linkage of all hospitalised atherothrombosis by other vascular history enabled determination of the first-ever and recurrent rates and disease risk ratios.4 Events were identified from the principal diagnosis at discharge and in-hospital death code where apparent, as previously validated by our group,7–10 and others.12 The sex-specific and age-specific findings are largely consistent within and between disease subtypes, although the risk ratios with wide CIs in 35–44 age groups should be interpreted with caution. Non-fatal brain/coronary attacks treated in the community were not included in the analyses but are expected to be small in number.6 Recognised underdiagnoses of peripheral arterial disease and cerebrovascular events may have resulted,13 thus diluting their relative contribution to the total hospitalised atherothrombosis burden. Excluding the very elderly has likely overestimated the dominance of the coronary events at the expense of the brain events, as would the associated elective admissions for the diagnostic (eg, stress testing, coronary angiography) and coronary revascularisation procedures. The inclusion of non-acute hospitalisations for greater coverage of elective procedures will have increased the absolute rates of events but had a negligible effect on relative comparisons.

Comparisons with other studies

The age distribution and medical profile of each disease subtype in this representative Australian study are consistent with other hospitalised population studies for myocardial infarction,14 stroke15 and peripheral arterial disease.16 We found little difference in the recurrent rates by sex and age, which is entirely consistent with the non-uniform findings of others.17–20 Differences in methodology likely account for the variability, including: sample size, case definition, all hospitalisations, age restrictions, ethnicity, risk factor profile, duration of follow-up and adjustment for covariates.

The comprehensive population OXVASC study1 confirms that the majority of atherothrombosis is incident (63% vs 57% in the present study), but led by stroke in that population, and that the rates rise steeply with age. The large multinational REACH Registry suggests that the coronary events dominate the atherothrombosis burden and supports incremental higher rates with other arterial disease involvement.21 In a separate REACH analysis,13 patients with peripheral disease experienced lower atherothrombosis rates than patients with stroke or coronary disease, independent of other vascular history. There were no differences in atherothrombosis rates by gender, possibly due to low enrolment of women in that study.22 Two smaller studies, the SIRO trial23 and MITICO study,24 reported stroke patients with polyvascular disease had higher rates of recurrence. For comorbidities, high proportions of the first-ever or recurrent atherothrombosis with hypertension, diabetes and chronic kidney disease have been variously identified in population and cohort studies.15 21 24–27

Implication of results

These sex-specific and age-specific rates and risk ratios for the first-ever and recurrent hospitalised atherothrombosis by vascular bed and the history of other vascular disease permit the comparisons of secondary over primary prevention. To minimise the disease burden on the population and hospitals we should aim to prevent the 56% of first-ever hospitalisations, in particular for the brain where it is 76%. The prevention of recurrent events is also very important (and not a mutually exclusive) priority, as they contribute a substantial volume of all hospitalisations, about 44%. The substantially higher risk ratios for recurrent events in persons with and without a history of other vascular disease magnify the scope for systematic secondary prevention across disease subtypes.

In Australia, increased uptake and adherence to antiplatelet, blood pressure-lowering and lipid-lowering medication in persons with established atherothrombosis, and long-term antismoking campaigns are priority targets for improving the cardiovascular outcomes.28 Two Australian general practice studies suggest that the application of these proven secondary prevention measures continues to be suboptimal.29 30 These findings are poignant given the high rates of recurrent events and raised risk ratios in men and women across the age span in the present study. Furthermore, the higher rates of a first-ever admission where there is a history of vascular disease in a different territory, particularly in the younger age groups, necessitate a more aggressive treatment of risk factors. There was no clear gender difference which may be because of the similarly high levels of comorbidities in men and women, or because the results were stratified by age, although there may be differences in the over 85 year age group which we have not investigated. Our findings have potential implications for the management of approximately 0.25 million (4.3% of the population) women and 0.5 million (8.6%) men in Australia hospitalised for atherothrombosis.6

Contributing to the high risk ratios of recurrent atherothrombosis in both sexes is that over half are hypertensive and around a quarter variously have diabetes, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation and heart failure, consistent with the other studies.15 17 21 26 Such comorbidities will likely complicate the clinical treatment during rehospitalisation and the subsequent chronic care.

Conclusions

We have shown in a population-based study of hospitalised atherothrombosis that the first-ever events predominate and that once vascular disease clinically manifests, the risk of further events in the same or another vascular bed is very high, even for the young, supressing the usual demographic effects. These findings highlight the need for a greater awareness among clinicians, patients and funders as to the level of risk related to recurrent events and detail the cross-risk associated with a prior hospitalisation in other vascular locations. These findings have important implications for prevention strategies, and the prioritising of resources for service provision and research, and they signal an upward trajectory in absolute numbers of events as the population ages. Data on hospital incidence, recurrence and event risk ratios across the vasculature will also permit modelling the effect of shared secondary preventive treatments, such as cardioprotective pharmacotherapy and lifestyle changes, on the total burden of hospitalised atherothrombosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Data Linkage Branch (Health Department of WA) for extraction and provision of the data used for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: TGB, MWK, GJH, PEN and JH conceived and designed the study; LJN, FMS, SH and TGB prepared the data for analysis; TGB and LJN undertook the data analysis and drafted the paper; MWK wrote the statistical plan and together with AB provided advanced statistical support; JH, GJH, PEN, PLT and FMS provided clinical advice; all authors contributed to the interpretation of data, reviewing article drafts and approving the final manuscript. TGB is the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (#572558) and The University of Western Australia.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by research ethics committees at The University of WA (#RA/4/1/1491) and the Department of Health WA (#2009/18).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The sharing of the linked data file is not permitted under the conditions under which the ethics for the study was granted.

References

- 1.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Silver LE, et al. Oxford vascular study. Population-based study of event-rate, incidence, case fatality, and mortality for all acute vascular events in all arterial territories. Lancet 2005;366:1773–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman M, et al. REACH Registry Investigators International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2006;295:180–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark A, Preen DB, Ng JQ, et al. Is Western Australia representative of other Australian States and Territories in terms of key socio-demographic and health economic indicators? Aust Health Rev 2010;34:210–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holman CDJ, Bass AJ, Rouse IL, et al. Population-based linkage of health records in Western Australia: development of a health services research linked database. Aust N Z J Public Health 1999;23:453–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases: the International Statistical Classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ (accessed 20 Jun 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nedkoff LJ, Briffa TG, Knuiman M, et al. Temporal trends in the incidence and recurrence of hospitalised atherothrombotic disease in an Australian population, 2000–2007. Heart 2012;98:1449–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamrozik K, Dobson A, Hobbs M, et al. Monitoring the incidence of cardiovascular disease in Australia. Report No. CVD Series 17 Canberra: AIHW, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanfilippo FM, Hobbs MST, Knuiman MW, et al. Can we monitor heart attack in the troponin era: evidence from a population-based cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2011;11:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattes E, Norman PE, Jamrozik K. Falling incidence of amputations for peripheral occlusive arterial disease in Western Australia between 1980 and 1992. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1997;13:14–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norman PE, Semmens JB, Lawrence-Brown MMD, et al. Long term relative survival after surgery for population based study abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia. BMJ 1998;317:852–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SAS version 9.3 for Windows. Cary, North Carolina, USA [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein LB. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM coding for the identification of patients with acute ischemic stroke: effect of modifier codes. Stroke 1998;29:1602–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatt DL, Peterson ED, Harrington RA, et al. Prior polyvascular disease: risk factor for adverse ischaemic outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt M, Jacobsen JB, Lash TL, et al. 25 year trends in first time hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction, subsequent short and long term mortality, and the prognostic impact of sex and comorbidity: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Silver LE, et al. Oxford Vascular Study. Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study). Lancet 2004;363:1925–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Kuijk J-P, Flu W-J, Welten GMJM, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with peripheral arterial disease with or without polyvascular atherosclerotic disease. Eur Heart J 2010;31:992–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, et al. ; WISE Investigators Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:S21–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacIntyre K, Stewart S, Capewell S, et al. Gender and survival: a population-based study of 201,114 men and women following a first acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:729–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Ascenzo F, Gonella A, Quadri G, et al. Comparison of mortality rates in women versus men presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:651–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, et al. Trends in the incidence and survival of patients with hospitalized myocardial infarction, Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979 to 1994. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:341–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, et al. ; REACH Registry Investigators One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2007;297:1197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrell J, Zeymer U, Baumgartner I, et al. ; REACH Registry Investigators Differences in management and outcomes between male and female patients with atherothrombotic disease: results from the REACH Registry in Europe. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011;18:270–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cimminiello C, Zaninelli A, Carolei A, et al. Atherothrombotic Burden and medium-term prognosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke: findings of the SIRIO Study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;33:341–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanco M, Sobrino T, Montaner J, et al. MÍTICO Study. Stroke with polyvascular atherothrombotic disease. Atherosclerosis 2010;208:587–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feigin VL, Lawes CMM, Bennett DA, et al. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:355–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. ; INTERHEART investigators Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries: case-control study. Lancet 2004;364:937–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, et al. ; INTERSTROKE investigators Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries: a case-control study. Lancet 2010;376:112–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Cardiovascular disease: Australian facts 2011. Cardiovascular disease series. Cat. no. CVD 53. Canberra: AIHW, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ademi Z, Liew D, Chew D, et al. on behalf of the REACH registry investigators Drug treatment and cost of cardiovascular disease in Australia. Cardiovas Ther 2009;27:164–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heeley EL, Peiris DP, Patel AA, et al. Cardiovascular risk perception and evidence–practice gaps in Australian general practice (AusHEART Study). Med J Aust 2010;192:254–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.