Abstract

An active line of current investigation is how the five-factor model (FFM) of personality disorder might be applied by clinicians and particularly, how clinically useful this model is in comparison to the existing nomenclature. The current study is the first to investigate the temporal consistency of clinicians’ application of the FFM and the DSM-IV-TR to their own patients. Results indicated that FFM ratings were relatively stable over six-months of treatment, supporting their use by clinicians, but also indexed potentially important clinical changes. Additionally, ratings of utility provided by the clinicians suggested that the FFM was more useful for clinical decision making than was the DSM-IV-TR model. We understand the clinical utility findings within the context of previous research indicating that the FFM is most useful among patients who are not prototypic for a personality disorder.

Keywords: temporal stability, therapist, five-factor model, FFM, test-retest, reliability, consistency

Personality disorders are currently conceptualized as “qualitatively distinct clinical syndromes” in the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000, p. 689). However, researchers have increasingly highlighted the limitations of this categorical model, including dissatisfaction by clinicians and questionable temporal stability (Clark, 2007; Trull & Durrett, 2005; Widiger & Trull, 2007). Because of this, mental health professionals have increasingly called for a change to this system. Research and theory have suggested that a dimensional model of personality disorder (PD) might provide a viable alternative to this current system (Clark, 2007; Krueger, Skodol, Livesley, Shrout, & Huang, 2007; Widiger & Samuel, 2005).

Although several dimensional models of PD have been proposed (see Widiger & Simonsen, 2005), one of the more heavily researched alternatives is the five-factor model of personality (FFM; McCrae & Costa, 2008). The FFM was developed as a model of general personality functioning and consists of five bipolar dimensions (i.e., neuroticism vs. emotional stability, extraversion vs. introversion, openness vs. closedness to experience, agreeableness vs. antagonism, and conscientiousness vs. undependability). These five broad domains can each be differentiated into underlying facets (e.g., the facets of agreeableness include trust vs. mistrust, compliance vs. aggression, altruism vs. exploitation, tender-mindedness vs. tough-mindedness, straightforwardness vs. deception, and modesty vs. arrogance). The FFM is a particularly robust dimensional model that has succeeded well in representing alternative personality theories and diverse collections of traits within a single, integrative, hierarchical model (John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008; Markon, Krueger, & Watson, 2005).

Research has demonstrated that the current PD categories can be translated into FFM language (Samuel & Widiger, 2008). However, as Clark (2007) noted, the true value of the FFM “lies in the dimensions themselves and their potential for deepening our understanding of PD traits, not in their ability to approximate demonstrably inadequate categories” (p. 232). To advance, the field needs studies that directly compare the current DSM-IV-TR with the FFM, as diagnostic systems. For example, comparisons have suggested that the FFM is less prone to gender biases than the categorical constructs of the DSM-IV-TR (Samuel & Widiger, 2009).

One important test for the FFM is its application by clinicians, who are the ultimate consumers of any diagnostic system. Clinicians have described patients in terms of the FFM for several studies, but a majority of these involved either hypothetical prototypes (Samuel & Widiger, 2004) or vignettes (Lowe & Widiger, 2009; Samuel & Widiger; 2009; Sprock, 2002; 2003). This research suggests that FFM ratings are reliable across clinicians, but the use of vignettes limits external validity. Only a few studies have collected clinicians’ FFM descriptions of their own patients. Some were conducted among national samples of clinicians via postal mail surveys (e.g., Mullins-Sweatt & Widiger, in press; Spitzer, First, Shedler, Westen, & Skodol, 2008) or within workshops (Blais, 1997). Such surveys are quite important for collecting a broad sampling of mental health professionals and establishing generalizable results. However, it might also be useful to conduct a more in-depth study among a group of clinicians providing services within a particular treatment setting. The intention of such a study would not be to investigate the broad applicability of the FFM within clinical practice, but rather to probe in greater depth the feasibility of its application by clinicians within a particular clinic. We are aware of only two published studies that have examined clinicians’ FFM descriptions of their own patients (i.e., Piedmont & Ciarrocchi, 1999; Soldz, Budman, Demby, & Merry, 1995).

Piedmont and Ciarrocchi (1999) reported on clinicians’ FFM descriptions of 132 substance-abusing patients at the beginning of a six-week outpatient treatment. This study supported the validity of the clinicians’ descriptions as they converged significantly with patient-reported NEO PI scores (Costa & McCrae, 1985). Soldz and colleagues (1995) also collected FFM ratings from five clinicians (i.e., two clinical psychologists, one social worker, and two psychiatric nurses) who provided ratings of 35 patients being treated for PDs within weekly group sessions. However, they collected FFM ratings at only point, precluding an investigation of their temporal consistency. Considering, recent findings highlighting the instability of the current PD categories (e.g., Grilo et al., 2004), it is particularly important that the research compare the temporal consistency of clinicians’ applications of the FFM and the DSM-IV PDs. While we expect that most constructs will be less stable in a clinical sample engaged in active treatment than a community sample, it is nonetheless important to demonstrate that clinicians’ ratings are somewhat stable over time. Thus, the goal of such an investigation is not to obtain consistency1 comparable to that obtained from non-clinical samples (which should be more stable across time) but to illustrate that ratings provided by clinicians are consistent enough to be valid indicators.

Clinical Utility

In addition to investigating the validity and temporal consistency of FFM ratings provided by clinicians, it is also crucial to understand its acceptability. Even the most valid model would fail in its purpose if not used effectively within clinical practice (First et al., 2004). A growing body of research is now considering the potential clinical utility of the FFM in comparison to the existing nomenclature (i.e., Sprock, 2003; Lowe & Widiger, 2009; Mullins-Sweatt & Widiger, in press; Rottman, Ahn, Sanislow, & Kim, 2009; Samuel & Widiger, 2006; Spitzer et al., 2008). These studies have utilized a variety of different methodologies including utility ratings based on vignettes, prototypes, and actual patients. This developing literature has produced somewhat inconsistent findings with some studies indicating an advantage for the FFM (e.g., Samuel & Widiger, 2006) and others suggesting the current DSM-IV system is more useful (e.g., Sprock, 2003). However, it is most informative to focus on the two studies that obtained utility ratings based on clinicians’ descriptions of their own patients.

Spitzer and colleagues (2008) were the first to examine clinicians’ ratings of utility after providing descriptions of their own patients. Spitzer and colleagues surveyed 12,000 members of the American Psychological and Psychiatric Associations and asked them to select an individual from their practice who had “significant personality problems (which may or may not meet threshold for a specific DSM-IV PD)” (p. 358). Three-hundred and ninety-seven clinicians (i.e., 3% of those surveyed) described a patient in terms of the DSM-IV PDs and several alternative dimensional models, including the FFM. One approach was to rate the patient on all of the DSM-IV PD diagnostic criteria; a second was to match the patient on a 5-point Likert scale to a paragraph description of a prototypic case of each of the 10 DSM-IV PDs (the sentences were from the respective diagnostic criterion sets); and a third approach was to complete a six-page rating form for the 30 facets of the FFM (Widiger, Trull, Clarkin, Sanderson, & Costa, 2002). After providing these descriptions, the clinicians rated the utility of the models 1) globally, 2) on five specific aspects, and 3) in comparison to the current DSM-IV categorical system.

Chi-square analyses did not detect significant differences between the FFM and the DSM-IV diagnostic criterion sets on any of the utility ratings. However, Spitzer and colleagues did report that the DSM-IV prototypal matching system was seen as more useful than the FFM (and the current DSM-IV criterion counting system) for professional communication and ease of use. These findings are at odds with both Sprock (2003) as well as Samuel and Widiger (2006) and suggest that further research should clarify the impact, in terms of clinical utility, of shifting to a dimensional model of PD.

A potential limitation of Spitzer et al. (2008) was the conflation of the constructs with the method of assessment. Whereas the prototypal matching required very little time, the FFM ratings required a consideration of six pages of material. Thus, the results might simply reflect a preference by the clinicians for the easier method. This might also explain why the clinicians much preferred the DSM-IV prototypal matching approach to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, even though there was virtually no difference in the content of the two approaches.

Mullins-Sweatt and Widiger (in press) addressed this limitation by collecting utility ratings from clinicians after they described their own patient using equivalent assessments (i.e., one page rating forms). Mullins-Sweatt and Widiger utilized a slightly different methodology as they asked the clinicians to describe a case that met criteria for one of the 10 DSM-IV PDs or was classified as personality disorder not otherwise specified (PDNOS). In their national survey of 85 psychologists, they found that the FFM was significantly more useful on three of the six utility variables, with no differences on the others. Not surprisingly, the utility was even more strongly in favor of the FFM for the PDNOS than for the PD cases.

This finding relates to a second potential limitation of the data collected by Spitzer and colleagues regarding the sample of patients. The sampling of actual patients was a strength, but the instruction was to choose a patient they knew “reasonably well who has significant personality problems.” It seems probable that this instruction would orient clinicians toward a patient for whom they had already developed a strong conceptualization in terms of the existing PD system. In fact, more than half of the clinicians reported seeing the patient for over 100 hours of treatment, and 48% had a borderline PD diagnosis (i.e., a personality disorder of considerable clinical interest and attention). Spitzer and colleagues do not indicate whether all of the patients selected were above threshold for a PD diagnosis, but it seems likely that this would be the case. Further research comparing the clinical utility of the current DSM-IV PD system and the FFM is needed that addresses this issue.

The current study seeks to build upon this previous research concerning clinicians’ use of personality disorder models in several important ways. First, collecting FFM and DSM-IV PD descriptions at multiple time points will provide the first data on the temporal consistency of clinicians’ FFM ratings. Consistent with self-report data from community (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000) and clinical (Morey et al., 2007) samples we hypothesize that the FFM will show considerable consistency across time, but will also prove sensitive to important clinical changes over the course of treatment. Second, we will extend the growing literature by providing a concurrent comparison of the clinical utility of the DSM-IV and FFM models that avoids the limitations of allowing clinicians to choose the patient they describe. We hypothesize that when personality ratings are provided for self-referred patients, rather than those chosen by the clinicians to represent existing conceptualizations of PD pathology, the results will further support the FFM’s clinical utility. Finally, the longitudinal collection of clinical utility ratings will allow the consideration of how useful each model is over the actual course of treatment.

Method

Procedure

We contacted therapists from a residential substance-abuse treatment facility to determine if they would be interested in referring patients for a larger study examining the convergent validity of the FFM and DSM-IV across assessment methods (Samuel & Widiger, in press). A sample of individuals with substance use disorders is useful for the current study because it is known to contain a rather high prevalence of DSM-IV PD pathology (Ball, Rounsaville, Tennen, & Kranzler, 2001). Therapists who expressed interest were provided flyers to distribute to their patients explaining the details of the study, including a phone number to contact the research team. In this way, the patients self-referred, rather than being specifically nominated by their clinicians. Interested patients provided written, informed consent and were enrolled2. Following the patient’s completion of the study protocol, we contacted their primary clinician and asked him or her to provide collateral ratings. Each therapist completed a demographic questionnaire, described the patient in terms of the FFM and DSM-IV PDs, and then rated the clinical utility of both models. Therapists provided written, informed consent and received $50 for their time and effort. At least six months after providing these initial ratings, the therapists were contacted again and were asked (if the patient was still in treatment) to describe the patient in terms of the FFM and the DSM-IV PDs and again rate the utility of both systems. Those therapists who completed this follow-up assessment received $20 in compensation.

Participants

Seventy-three individuals were recruited from a residential substance abuse treatment program within a medium-sized city in the southeastern United States. They ranged in age from 19 to 60, with a mean of 35.0 years (SD = 8.5). They were primarily Caucasian (71%), with 25% indicating African-American, and three providing the response of “other.” Ten clinicians, who served as the primary therapists for these patients, provided clinical assessments. The number of patients assessed by each clinician ranged from a low of one to a high of 18, with a median of six. These clinicians were all female, and predominantly Caucasian, but two were Asian-American, and one was African-American. Level of training and experience varied. Two had doctoral degrees, six had Master’s degrees, and two had bachelor’s degrees but were enrolled in 10 advanced degree programs. Four obtained their training in counseling psychology, four in social work, and two in clinical psychology. Their experience ranged from a low of one year to a high of 10, with a mean of 3.2 years. The percentage of working time they spent providing clinical services ranged from a low of 20% to a high of 100%, with a mean of 57%. Ninety percent of the clinicians identified their theoretical orientation as cognitive, while 80% also listed behavioral, 60% interpersonal, 40% humanistic, and 30% psychodynamic. They rated their familiarity with each model on a 1–5 scale ranging from not at all familiar to very familiar. The clinicians were more familiar with the DSM-IV PDs (M = 4.2; SD = .8) than the FFM (M = 2.7; SD = 1.2), t (9) = 4.0, p = .003. This familiarity rating for the DSM-IV PDs was comparable to the values obtained in previous studies of doctoral level clinical psychologists (e.g., 4.26 from Samuel & Widiger, 2006; 3.97 from Sprock, 2002; 4.06 from Sprock, 2003).

We examined the prevalence rates of the DSM-IV-TR PDs, according to the clinicians, to determine the level and type of pathology present at baseline (Samuel and Widiger [in press] presents data on the agreement between these clinician ratings and semi-structured interview assessments). The following values indicate the number of individuals who received a rating of 3 (i.e., threshold) for each PD. According to this metric at least one individual met criteria for each DSM-IV-TR diagnosis. Borderline was the most prevalent with 23 individuals (32%) meeting criteria, but avoidant (18 patients; 25%), paranoid (14 patients; 19%), dependent (13 patients; 18%), OCPD (11 patients; 15%), and histrionic (10 patients; 14%) were also common. When asked to provide a “final PD diagnosis,” the clinicians indicated that 19% of the sample had one or more of the PD categories, 23% were PDNOS, and 58% were subthreshold.

Materials

DSM-IV Personality Disorder Rating Form (DSMRF)

The DSM-IV PD rating form (DSMRF) asks the clinician to rate the extent to which the patient exhibits characteristics of each of the ten PDs. Although the DSM-IV model currently uses a categorical approach to diagnosis, the DSMRF uses a 1–5 Likert scale to provide dimensional ratings of each disorder where 1 = absent, 2 = subthreshold, 3 = threshold, 4 = moderate, and 5 = prototypic. The clinician also assigns a final PD diagnosis indicating that the patient receives “one or more of the 10 diagnoses,” “PDNOS,” or “no PD diagnosis.” Because each PD was assessed only by a single-item, internal consistency statistics could not be computed. Clinicians completed the DSMRF at baseline and the 6-month follow-up.

Five-Factor Model Rating Form (FFMRF)

The FFMRF was a one-page form consistent with the DSMRF that asks the therapist to describe an individual on the 30 facets of the FFM using a 1–5 Likert-type scale where 1 = extremely low, 2 = low, 3 = neutral, 4 = high, and 5 = extremely high. To assist the therapists in providing these ratings, two adjective descriptors are included at both poles of each facet. We summed the facet ratings to create scores for the five FFM domains. The internal consistencies for the therapists’ ratings of the FFM domains were reasonable, with a median of .78, but ranged from a low of .61 (neuroticism) to a high of .83 (conscientiousness). The FFMRF was completed at baseline and 6-month follow-up.

Clinical Utility Questionnaire

After completing the DSMRF and the FFMRF, the clinicians were asked to rate both the DSM-IV and the FFM descriptions on each aspect of clinical utility. This questionnaire assessed components of clinical utility outlined by First et al. (2004). The six questions that were addressed were: 1) How easy do you feel it was to apply the system to this individual, 2) how useful do you feel the system would be for communicating information about this individual with other mental health professionals, 3) how useful do you feel this system would be for communicating information about the individual to him or herself, 4) how useful is this system for comprehensively describing all the important personality problems the individual has, 5) how useful would this system be for helping you to formulate an effective intervention for this individual, and 6) how useful was this system for describing the individual’s global personality. These ratings were provided on a 1–5 Likert scale, where 1 = not at all useful, 2 = slightly useful, 3 = moderately useful, 4 = very useful, and 5 = extremely useful.

Follow-up Clinical Utility Questionnaire

This brief rating form, designed for the current study, contained four items that asked the clinicians to reflect on their previous use of each model. The items included 1) How likely would you be to use this system again with future clients, 2) how useful was this system for enhancing your clinical decision making, 3) how useful was this system for describing what you focused on in therapy with this client, and 4) how useful was this system for determining what interventions would be successful for this client. These ratings used the same 1–5 Likert scale as the initial utility questionnaire.

Results

Baseline Clinical Utility

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for each of the six utility variables for both the DSM-IV and FFM. The primary result of interest is, of course, whether the utility ratings were significantly higher for one model or another. However, considering the findings of Mullins-Sweatt and Widiger (in press) as well as Sprock (2003) we sought to control for how prototypic the individual was for a PD diagnosis. Thus, we entered the “final PD diagnosis” variable (e.g., one or more PD diagnoses, PDNOS, or no PD diagnosis) from the DSMRF as a between-subjects factor. The three levels of this variable provide an index of how prototypic the therapist felt the client was for a DSM-IV PD. This was tested in a 3 (prototypicality) × 2 (model) MANOVA with the models (e.g., DSM-IV and FFM) treated as repeated measures. The within subjects main effect for model was significant [F (6, 56) = 33.9, p < .001], indicating an overall difference in the utility ratings provided for the FFM and DSM-IV. In contrast, the between-subjects main effect for prototypicality was non-significant [F (12, 114) = 1.5, p = .14], indicating that this did not influence the utility ratings, independent of model. The interaction term between prototypicality and model was also non-significant, F (12, 114) = .8, p = .61.

Table 1.

Clinicians' Baseline Clinical Utility Ratings

| Clinical Utility Variable | DSM | FFM | F | sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | mean | SD | |||

| Ease of Application | 2.60 | 1.00 | 4.13 | 0.80 | −87.7 | < .001 |

| Professional Communication | 2.83 | 0.99 | 4.15 | 0.90 | −67.6 | < .001 |

| Client Communication | 2.23 | 0.85 | 4.29 | 0.87 | −187.2 | < .001 |

| Comprehensive of Difficulties | 2.45 | 0.96 | 4.01 | 0.99 | −86.9 | < .001 |

| Treatment Planning | 2.59 | 0.90 | 4.08 | 0.92 | −93.9 | < .001 |

| Global Personality Description | 2.26 | 0.81 | 4.29 | 0.87 | −206.5 | < .001 |

Notes: DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - 4th ed., personality disorder model; FFM = Five-Factor Model; mean = mean utility rating; SD = standard deviation; Ease of Application = "How easy do you feel it was to apply the system to this individual?"; Professional Communication = "How useful do you feel the system would be for communicating information about this individual with other mental health professionals?"; Client Communication = "How useful do you feel this system would be for communicating information about the individual to him or herself?"; Comprehensive of Difficulties = "How useful is this system for comprehensively describing all the important personality problems this individual has?"; Treatment Planning = "How useful would this system be in helping you to formulate an effective intervention for this individual?"; Global Personality Description = "How useful was this system for describing the individual’s global personality?"; All utility ratings on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) Likert Scale.

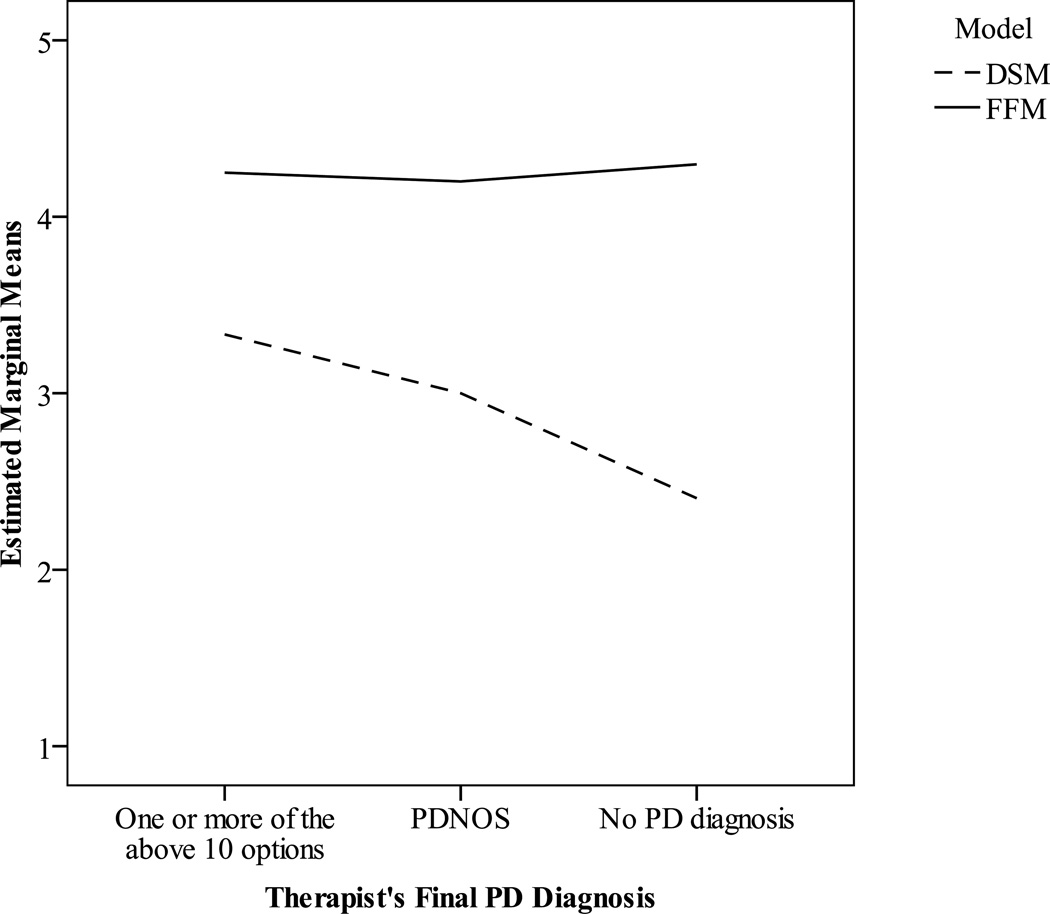

Table 1 presents within-subjects contrasts for model and indicate that the FFM was higher than the DSM-IV on all six clinical utility variables. Contrasts for the model by prototypicality interactions revealed a significant interaction for “communication with professionals” [F (2, 61) = 2.7, p < .05] and an examination of the means suggested that this was driven by differences in utility ratings for the DSM-IV model. Figure 1 illustrates that the mean utility rating for the FFM was constant, regardless of whether the individual being rated met criteria for a particular DSM-IV PD category, was better classified by the PDNOS label, or did not have a PD diagnosis. In contrast, the mean utility rating for the DSM-IV model was highest for those cases deemed to have one or more PD diagnoses and was lower for individuals labeled PDNOS and those without a PD diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Clinicians’ Mean Utility Ratings for Professional Communication

Temporal Consistency

At the 6-month follow-up clinicians provided FFM and PD descriptions as well as utility ratings for 31 of the original 73 patients (42%). The absence of data indicated that the same clinician was no longer actively seeing the individual for therapy. For 28 cases this was because the patient was no longer in therapy (i.e., dropped out of treatment without consulting the therapist or had terminated successfully). In 12 cases the therapist switched clinical facilities and there were two instances in which a clinician did not return the forms.

We considered temporal consistency using three methods to examine distinct aspects of stability (Roberts, Wood, & Caspi, 2008). First, we computed Pearson correlations between the scores (e.g., rank-order) to determine the relative consistency of these scores across the sample. Table 2 provides the means and standard deviations of the PD ratings at both baseline and the six-month follow-up for those 31 patients. These correlations are in the fifth data column and range from −.22 (schizoid) to .66 (antisocial). These consistency coefficients were significant for seven PDs, but rank-order consistency was weak for the schizoid, schizotypal, and narcissistic PDs. This might reflect that these three PDs had the lowest mean values at both baseline and follow-up. Because these means were only slightly above the lower end of the rating scale, it is possible that a restricted range reduced these correlations. Table 3 provides the rank-order correlations for the FFM domains and facets. These coefficients for the domains were significant for extraversion (.54), agreeableness (.57), openness (.67), and conscientiousness (.53), but not for neuroticism (r = .23). At the facet level, 22 of the 30 correlations were significant and all but one (e.g., anxiousness) was above .20. The overall median was .40.

Table 2.

Means and Temporal Consistency Coefficients for Clinicians' Personality Disorder Ratings over Six Months

| Baseline | Follow-up | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | sd | m | sd | r | F | d | |||

| Paranoid | 1.81 | .98 | 1.61 | .62 | .37 | * | 1.3 | −.24 | |

| Schizoid | 1.39 | .62 | 1.23 | .67 | −.22 | .8 | −.25 | ||

| Schizotypal | 1.45 | .81 | 1.13 | .43 | .12 | 4.2 | * | −.50 | |

| Antisocial | 1.58 | .99 | 1.55 | 1.03 | .66 | *** | .0 | −.03 | |

| Borderline | 2.16 | 1.44 | 1.68 | 1.01 | .31 | 3.3 | −.39 | ||

| Histrionic | 1.77 | 1.28 | 1.39 | .67 | .65 | *** | 4.7 | * | −.38 |

| Narcissistic | 1.42 | .81 | 1.35 | .55 | .18 | .2 | −.09 | ||

| Avoidant | 2.23 | 1.43 | 1.90 | 1.04 | .53 | ** | 2.1 | −.26 | |

| Dependent | 1.77 | 1.15 | 1.45 | .72 | .65 | *** | 4.2 | * | −.34 |

| OCPD | 1.55 | .96 | 1.58 | 1.15 | .43 | * | .0 | .03 | |

Notes: The table presents results only for those 31 individuals for which follow-up data were available. DSM-IV PD ratings were on 1–5 scale where 1 = absent, 2 = subthreshold, 3 = threshold, 4 = moderate, and 5 = prototypic. r = temporal stability coefficient, computed using Pearson correlation. F = Repeated measures ANOVA for mean changes from baseline to follow-up. d = Cohen's d estimate of effect size.

= p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Table 3.

Means and Temporal Consistency of Clinicians' FFM Ratings Over Six Months

| Baseline | 6-months | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | sd | m | sd | r | F | d | |||

| Neuroticism | 3.04 | 0.65 | 3.01 | 0.51 | 0.23 | 0.0 | −.05 | ||

| Anxiousness (n1) | 3.16 | 1.07 | 2.97 | 0.87 | 0.11 | 0.7 | −.20 | ||

| Angry Hostility (n2) | 3.00 | 0.97 | 2.81 | 0.83 | 0.37 | * | 0.6 | −.21 | |

| Depressiveness (n3) | 3.13 | 0.96 | 3.19 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.3 | .07 | ||

| Self-Consciousness (n4) | 2.68 | 0.79 | 2.90 | 0.83 | 0.56 | ** | 2.7 | .28 | |

| Impulsivity (n5) | 3.32 | 1.08 | 3.23 | 0.99 | 0.27 | 0.1 | −.09 | ||

| Vulnerability (n6) | 2.94 | 1.06 | 2.97 | 0.75 | 0.58 | ** | 0.5 | .04 | |

| Extraversion | 3.38 | 0.51 | 3.42 | 0.55 | 0.54 | ** | 0.2 | .07 | |

| Warmth (e1) | 3.61 | 0.84 | 3.42 | 0.81 | 0.25 | 0.8 | −.23 | ||

| Gregariousness (e2) | 3.45 | 0.85 | 3.48 | 0.85 | 0.70 | *** | 0.0 | .04 | |

| Assertiveness (e3) | 3.23 | 0.99 | 3.52 | 0.63 | 0.40 | * | 2.0 | .35 | |

| Activity (e4) | 3.29 | 0.69 | 3.27 | 0.83 | 0.39 | * | 0.0 | −.03 | |

| Excitement Seeking (e5) | 3.29 | 0.94 | 3.26 | 0.96 | 0.47 | ** | 0.0 | −.03 | |

| Positive Emotions (e6) | 3.42 | 0.81 | 3.55 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.7 | .18 | ||

| Openness | 3.32 | 0.54 | 3.20 | 0.46 | 0.67 | *** | 2.3 | −.22 | |

| Fantasy (o1) | 3.03 | 0.91 | 3.13 | 0.85 | 0.38 | * | 0.1 | .11 | |

| Aesthetics (o2) | 3.23 | 0.72 | 3.26 | 0.68 | 0.70 | *** | 0.1 | .05 | |

| Feelings (o3) | 3.74 | 0.77 | 3.74 | 0.73 | 0.41 | * | 0.0 | .00 | |

| Actions (o4) | 3.26 | 0.93 | 3.03 | 0.84 | 0.68 | *** | 2.0 | −.26 | |

| Ideas (o5) | 3.23 | 0.76 | 2.90 | 0.60 | 0.49 | ** | 5.5 | * | −.47 |

| Values (o6) | 3.42 | 0.81 | 3.16 | 0.90 | 0.41 | * | 2.4 | −.30 | |

| Agreeableness | 3.24 | 0.77 | 3.02 | 0.45 | 0.57 | ** | 3.7 | −.35 | |

| Trust (a1) | 2.90 | 1.16 | 2.77 | 0.76 | 0.65 | *** | 0.4 | −.13 | |

| Straightforwardness (a2) | 3.45 | 1.03 | 3.23 | 0.99 | 0.39 | * | 1.7 | −.22 | |

| Altruism (a3) | 3.45 | 0.96 | 3.23 | 0.67 | 0.51 | ** | 1.7 | −.27 | |

| Compliance (a4) | 3.35 | 0.98 | 3.23 | 0.67 | 0.43 | * | 0.6 | −.15 | |

| Modesty (a5) | 3.13 | 0.76 | 2.77 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 4.8 | * | −.53 | |

| Tender-mindedness (a6) | 3.13 | 0.85 | 2.87 | 0.72 | 0.52 | ** | 3.5 | −.33 | |

| Conscientiousness | 3.34 | 0.60 | 3.33 | 0.59 | 0.53 | ** | 0.0 | −.03 | |

| Competence (C 1) | 3.45 | 0.81 | 3.29 | 0.74 | 0.39 | * | 2.7 | −.21 | |

| Order (c2) | 3.35 | 0.71 | 3.29 | 0.64 | 0.21 | 0.4 | −.10 | ||

| Dutifulness (c3) | 3.45 | 0.81 | 3.32 | 0.65 | 0.22 | 0.6 | −.18 | ||

| Achievement (c4) | 3.52 | 0.81 | 3.45 | 0.68 | 0.47 | ** | 0.2 | −.09 | |

| Self-discipline (c5) | 3.19 | 0.83 | 3.39 | 0.72 | 0.60 | *** | 1.7 | .25 | |

| Deliberation (c6) | 3.10 | 0.94 | 3.23 | 0.72 | 0.36 | * | 0.6 | .15 | |

Notes: The table presents results only for those 31 individuals for which follow-up data were available. FFM ratings were on a 1–5 scale where 1 = extremely low, 2 = low, 3 = neutral, 4 = high, and 5 = extremely high. r = temporal stability coefficient, computed using Pearson correlation. F = Repeated measures ANOVA for mean changes from baseline to follow-up. d = Cohen's d estimate of effect size.

= p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Next, we compared the ratings between the two time points to examine their absolute consistency. Several of the PDs had mean level decreases and a repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that differences were significant for schizotypal, histrionic, and dependent PD (see Table 2). However, it is perhaps more useful to examine the final column which presents the effect size estimates in terms of Cohen’s d. Using the “t-shirt” guidelines provided by Cohen (1992), the effect for schizotypal is considered medium (i.e., > .50), while those for histrionic, borderline, dependent, avoidant, schizoid, and paranoid are considered small (> .20). Table 3 indicates that mean-level changes were non-significant for all five FFM domains, but that agreeableness (d = −.35) and openness (d = −.22) showed small shifts. Because FFM traits can be maladaptive in both directions, a less extreme score is potentially more adaptive. For both domains, the shift was toward the midpoint of the scale (i.e., 3). At the facet level, only modesty from agreeableness and openness to ideas evinced significant changes. Modesty was the only facet with a medium effect, while 13 other facets showed small effects. Of these 14 facets with notable change, 10 became less extreme (i.e., closer to 3), while four became more extreme. Specifically, the extraversion facet of assertiveness and the conscientiousness facet of self-discipline both showed an overall increase (i.e., were higher than 3 at baseline and became more extreme) while modesty and the neuroticism facet of angry hostility both decreased.

Finally, we computed ipsative consistency correlations to index relative change within each individual. This involved correlating each individual’s profile from baseline with that from the six-month follow-up. For the DSM-IV PDs, these ipsative consistency coefficients ranged from −.17 to .97, with a median of .55 across the sample. The ipsative values for the FFM domain ratings ranged from −.92 to .94, and had a median value of .62. For the FFM facet ratings, the ipsative consistency coefficients ranged from −.47 to .84, with a median of .44.

Follow-up Clinical Utility

The means and standard deviations for the four utility variables included in the six-month follow-up are in Table 4. As with the baseline ratings, a 3 (prototypicality) × 2 (model) MANOVA was conducted with the models treated as repeated measures. The within-subjects main effect for model was significant, F (4, 18) = 18.0, p < .001, while the between-subjects prototypicality factor and the interaction term were non-significant. Contrasts revealed that the FFM was significantly higher than the DSM-IV for each of the four utility variables. This indicates that clinicians found the FFM more useful than the DSM-IV for enhancing their clinical decision making, determining the appropriate intervention, and describing the focus of treatment. Contrasts for the prototypicality interactions were non-significant, suggesting that the follow-up utility ratings for the FFM and DSM-IV were unaffected by the how prototypic the individual was for a PD diagnosis at baseline.

Table 4.

Clinicians' Follow-up Clinical Utility Ratings

| Clinical Utility Variable | DSM | FFM | F | sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | mean | SD | |||

| Likely to Use Again | 3.84 | 0.97 | 4.45 | 0.68 | −6.80 | .014 |

| Enhanced Decision Making | 2.90 | 0.70 | 4.23 | 0.72 | −38.03 | < .001 |

| Described Tx Focus | 2.58 | 0.72 | 4.19 | 0.75 | −58.50 | < .001 |

| Intervention Determination | 2.65 | 0.61 | 4.23 | 0.80 | −53.36 | < .001 |

Notes: DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - 4th ed., personality disorder model; FFM = Five-Factor Model; mean = mean utility rating; SD = standard deviation; likely to use again = "How likely would you be to use each system again with future clients?"; Enhanced Decision Making = "How useful was each system in enhancing your clinical decision making?"; Described Tx Focus = "How useful was each system for describing what you focused on in therapy with this client?"; Intervention Determination = "How useful was each system in determining which interventions would be successful for this client?"; All utility ratings on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) Likert Scale.

Discussion

Temporal Consistency

Although previous research has suggested that clinicians can apply the FFM to their own patients, these investigations have been solely cross-sectional in nature. In the current study, we sought to extend this research by exploring, in depth, the application of the FFM and DSM-IV PD models within a particular treatment setting and considering their temporal consistency from a variety of perspectives. We used three different metrics that provide unique information on the consistency of the therapists’ ratings for both models (Roberts et al., 2008).

Rank-order consistency coefficients provide a relative index of stability at the population level and estimate the temporal consistency of individuals’ standings on a given scale relative to each other. By this metric, both the FFM and DSM-IV PD descriptions were relatively stable over time, with perhaps the exception of a few PDs with particularly low base rates. The FFM scores also obtained moderate consistency at the domain level, except for neuroticism (i.e., .23), which was lower within this clinical sample than in previous studies (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). It is perhaps not surprising that neuroticism is less stable for patients engaged in active treatment than within community samples, but it is encouraging that the other four domains obtained values that were consistent with those from Roberts & DelVecchio (2000). In fact, the rank order correlations for extraversion (.54), openness (.67), agreeableness (.57), and conscientiousness (.53) were extremely similar to meta-analyzed values reported across more than 50 samples (e.g., .54, .51, .54, .51, respectively). This suggests that therapist’s FFM ratings show consistency similar to those from self-report within community samples.

The rank-order consistency correlations for the FFM domains were, though, slightly lower than those reported within other clinical samples (Morey et al. 2007; De Fruyt, van Leeuwen, Bagby, Rolland, & Rouillon, 2006). For example, the values from Morey et al (2007) ranged from .68 to .77 within a large sample of individuals with PDs. However, the lower values obtained in the current study are difficult to compare directly because the individuals sampled by Morey and colleagues, while high in personality pathology, were not necessarily engaged in active treatment. De Fruyt et al (2006) sampled a similarly large sample of depressed patients who were being actively treated with pharmacotherapy. The rank order consistency coefficients from that study were slightly lower (r = .57) for neuroticism, but were similar to those reported by Morey et al (2007) for the other four domains (e.g., .66 to .77). This suggests that, as was found in the current study, neuroticism is the only domain that demonstrates less rank-order stability within a clinical sample. Of course, it is crucial to note that the FFM scores from Morey et al. and De Fruyt et al were collected via self-report, using a 240-item instrument (e.g., the NEO PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992). In contrast, the scores in the current study were collected from clinicians using a one-page rating form. Future research is needed to determine whether the somewhat lower rank-order stability in the current study is due to differences in FFM instruments or the source of the ratings. Individuals might be more prone to seeing stability in their own personalities, whereas clinicians are better able to detect meaningful changes.

Although rank-order correlations provide a commonly used and relatively straightforward metric of consistency, they might miss important mean-level changes. This does appear to be the case for at least some of the DSM-IV PD ratings, as scores for histrionic and dependent showed significant rank-order consistency, but the mean scores also decreased significantly. In contrast, antisocial scores had comparable rank-order correlations, yet the mean-level change was nearly zero. The FFM scores demonstrated moderate mean-level consistency, but also indexed potentially important clinical change. Fourteen of the 30 facets and two of the five domains obtained at least a small effect size and all but four of these changes were in the direction of reduced extremity (i.e., closer to the midpoint rating of 3). Even the exceptions are potentially understandable as these shifts were in the direction of improved personality functioning (e.g., higher levels of assertiveness and self-discipline).

Finally, because both rank-order correlations and mean comparisons are concerned with consistency at the population level, we also calculated ipsative consistency correlations. These analyses did suggest intra-individual variability for both models. This indicates that individuals shifted in terms of their standing on each scale, relative to the other scales. Perhaps surprisingly, the DSM-IV PD ratings obtained a mean ipsative consistency value (.55) that was higher than the FFM facets (.44), but was lower than the FFM domains (.62). This suggests that while an individual’s PD scores generally decreased over time, the intra-individual pattern of relationships among the constructs changed less than for the FFM facet scores. The ipsative consistency for the FFM domains (median = .62) was also somewhat lower than a previous study (Robins, Fraley, Roberts, & Trzniewski, 2001), which noted a median value of .76 across four years in a sample of undergraduates. It is perhaps not surprising that individuals actively engaged in treatment would show more change within their profile than a group of undergraduate students as the inconsistency might be related to the individuals’ starting points on the traits. Those who display more maladaptive personality patterns are also more prone to ipsative change over time, so the clinical nature of the sample might drive greater change within each individual’s FFM profile. The small, but meaningful, changes noted above for many of the FFM facets buttress this hypothesis. These facet scores, while sometimes opposite in their absolute direction of change, typically became more adaptive. For example, a decrease in angry hostility combined with an increase in self-discipline is a clinically preferable outcome, but would reduce the ipsative consistency of a profile. For this reason, variables assessed in a clinical sample might show less ipsative consistency than within a group of community volunteers.

Taken together these consistency findings further indicate that clinicians are able to describe their patients using the FFM. Previous research has indicated that clinicians’ FFM ratings are reliable across raters (Samuel & Widiger, 2004, 2006; Sprock, 2002, 2003) and converge reasonably well with other methods (Piedmont & Ciarrocchi, 1999; Soldz et al., 1995). The current results go further and suggest that these ratings are relatively stable across time, but are potentially less stable than self-reported FFM scores within treatment samples (e.g., De Fruyt et al., 2006). In this way, it appears that therapists ratings might be better able to detect important clinical change (e.g., increased assertiveness), than self-report. These properties lend additional credibility and support for the FFM’s use in clinical settings.

Clinical Utility

We also found that clinicians rated the FFM as more useful than the DSM-IV for describing their patients. This finding was consistent across all six utility variables, including ease of application, communication with professionals, communication with clients, comprehensive description of personality difficulties, treatment planning, and global personality description. These results extended those of Spitzer et al. (2008) and Mullins-Sweatt and Widiger (in press) by collecting DSM-IV and FFM descriptions using equivalent rating forms. However, the current results were even stronger for the FFM than in previous studies.

There are two possible explanations as to why the utility findings in the current study were more robustly in favor of the FFM than in previous research. One possibility is that because the clinicians provided ratings on multiple patients they may have become more familiar with (and perhaps favorable toward) the FFM over the course of the study. However, the data do not support this hypothesis as the order in which the clinicians provided ratings did not have a significant impact on the utility of the FFM or DSM-IV. In other words, the utility ratings provided by an individual clinician were not significantly different for the first client they described than for their third, fourth, or even fourteenth client. Perhaps the most likely explanation for the differences between the results is that the patients in the current study were less prototypic for the DSM-IV PD categories than those the clinicians chose to describe in both Spitzer et al. (2008) and Mullins-Sweatt & Widiger (in press).

Mullins-Sweatt and Widiger (in press) explicitly asked one group of clinicians to select a patient who met criteria for at least one of the ten DSM-IV PDs and another group to select a patient classified as PDNOS. Not surprisingly, the FFM obtained even higher utility ratings within the PDNOS group as, by definition, they did not fit within one of the current PD categories. Nonetheless, it is likely that the individuals described by the clinicians in Mullins-Sweatt and Widiger, while perhaps not prototypic, did possess significant levels of personality pathology and had been previously conceptualized in terms of the DSM-IV model. The patients described in the study by Spitzer and colleagues (2008) were selected by their therapists. While the patients were also likely not prototypic PD cases, the design may have pulled for patients that exhibited clear and even similar types of personality pathology (e.g., 48% of the clinicians selected a patient with a chart diagnosis of borderline PD). Had this study instructed the clinician to describe the patient they had seen most recently the results might have been quite different.

In contrast, the patients in the current study self-selected for participation and the result was a much wider range, but lower severity, of personality pathology (i.e., the clinicians provided the diagnosis of PDNOS for 23% of the patients and indicated that 58% had significant personality pathology but did not reach threshold for a particular DSM-IV PD). It is this difference in prototypicality that we hypothesize drives differences between the utility ratings within the current study and those from previous research.

We also noted an interaction between the utility rating for professional communication and prototypicality, such that the DSM-IV was more useful for cases that met criteria for a PD diagnosis than for those that did not. This supports the findings of Sprock (2003) indicating that perceived utility of the DSM-IV PD categories varies with the extent to which the individual being described fits the model. It is perhaps not surprising that prototypicality should influence the results of a clinical utility study. At the one end of the spectrum, the current DSM-IV model should be most useful for cases that are prototypic for a given PD (e.g., the vignettes studied by Sprock, 2003). In contrast, those that are non-prototypic might not possess any notable personality pathology. For such an individual, it is intuitive that the FFM would be more clinically useful and easier to apply than the DSM-IV PD categories. Nonetheless, research has suggested that the individuals within clinical settings are not nearly this black and white (Westen & Arkowitz-Westen, 1998; Verheul & Widiger, 2004). As such, encountering either a patient with a complete absence of personality pathology or a prototypic case of a particular PD is unlikely. In this sense, the current sampling procedure may more closely approximate the “typical” patient seen in clinical practice.

Follow-up Clinical Utility Ratings

In previous studies, clinicians have provided utility ratings immediately after describing the person using both the FFM and DSM-IV. Thus, the ratings of clinical utility for the FFM are rather speculative, in that they reflect opinions about how useful this information might be in their future sessions. However, a unique contribution of the current study was the collection of additional utility ratings six months after the initial descriptions for each model. The longitudinal data collection allows for a consideration of how useful the clinicians found the DSM-IV and FFM during the actual course of treatment. The FFM was more useful than the DSM-IV on these follow-up questions, indicating specifically that the FFM had better guided the focus of treatment, determined the appropriate intervention, and enhanced decision-making.

The finding that the FFM obtained higher ratings for a variable such as determining an appropriate intervention may be somewhat surprising considering there is little research or theory on how one might use FFM constructs to inform treatment (Sanderson & Clarkin, 2002; Widiger & Lowe, 2008). Thus, it is not clear precisely how or by what mechanism the clinicians felt the FFM helped plan treatment. One possibility is simply that the DSM-IV system is so vacant of useful treatment information that any valid information is more clinically useful. Consistent with this notion, Verheul (2005) noted that “the most frequent criticisms of the DSM-IV among clinicians, at least in the Netherlands, is that the available categories and clusters do not direct treatment selection or planning at all” (p. 292). The results of an international survey of clinicians regarding their use of and attitudes toward the DSM-IV also support this conclusion. Maser, Kaelber, and Weise (1991) surveyed mental health professionals in 42 countries and found that they considered Axis II the most problematic portion of the manual.

In an attempt to clarify these utility ratings, we contacted several of the clinicians after they had completed their participation and asked them how the FFM had helped them plan treatment. One clinician explained, “The DSM is just so categorical that it doesn’t fit most of my clients.” Another clinician echoed and expanded on these thoughts stating the reason for her rating was “mostly because the DSM is just not that useful. It doesn’t inform treatment.” However, the utility ratings are not purely reflective of weaknesses on the part of the DSM-IV system; the same clinician went on to say she found “the FFM language more helpful for talking with her clients and tailoring an individualized treatment.” A third clinician explained that the FFM allowed for a “focus on individual issues” and provided a specific example of how several of her clients would qualify for a borderline PD diagnosis, but still exhibit vast differences on an important trait like impulsivity. This particular example echoes the hypothetical cases described by Krueger and Eaton (2010) in which it was suggested that FFM facets might be helpful in further differentiating patients who shared the same borderline diagnosis. In sum, while it may be that a general dissatisfaction with the DSM-IV PD nomenclature is a primary driving force of the utility ratings provided within this study, it also appears that the FFM may have notable strengths for providing nuanced and individualized descriptions that allow it to influence treatment decisions.

Limitations and Future Directions

A strategic decision in the current methodology was to avoid the potential confound of asking clinicians to select the patients they would describe. Previous clinical utility studies that have taken that approach have, either intentionally (Mullins-Sweatt & Widiger, in press) or unintentionally (Spitzer et al., 2008), ended up with samples that are biased toward patients whom the clinicians have already conceptualized within the current PD model. In order to avoid this outcome, we chose a clinical sample known to have high rates of personality pathology (e.g., Ball et al., 2001) and then allowed patients to self–refer. While this approach leads to a prevalence rate that is more externally valid, it does not ensure the adequate sampling of individuals with diagnosable PDs. Although the current group of patients exhibited a great deal of PD pathology, it did not represent a full range and level of severity. Perhaps consistent with any sample from clinical practice, there were not many (if any) prototypic cases of DSM-IV PDs. Considering the influence of prototypicality on clinical utility findings across several studies, it would be useful for future research to vary systematically the degree of prototypicality.

The current results concern a single group of clinicians, who varied in terms of their educational background and level of experience. Although their ratings of familiarity with the DSM-IV PDs is equivalent to clinicians from previous studies (e.g., Sprock, 2003), it is possible that the lower utility of the DSM-IV in the current study might reflect that the clinicians had relatively fewer years of experience and less extensive educational training. However, this would not solely explain differences from previous studies as Samuel & Widiger (2006) surveyed practicing psychologists with a great deal of experience and reported that the FFM was more useful than the DSM-IV. In any event, this is but one sample of mental health clinicians and replication of these findings within samples that vary in terms of their educational background, experience, theoretical orientation, and other demographic variables is warranted. Relatedly, both the patients and therapists were from a residential substance abuse treatment facility, so future research with other clinical settings would be quite helpful. There might also have been unknown factors that influenced which clinicians and patients volunteered for the study and this could have affected the results. Additionally, the number of patients described varied across the clinicians, such that some had a greater impact on the results than others. Nonetheless, the fact the results from the current study were in line with previous estimates discount the likelihood these factors had an appreciable impact on our findings.

Finally, the inclusion of follow-up utility ratings provided a more externally valid test of how these two models influence decision making within general practice. Nonetheless, the heavy attrition that characterizes substance abuse treatment limits the conclusions that can be drawn with regard to both temporal consistency and clinical utility. In addition, the clinical utility results from the current study are still ratings of utility. The ultimate test of any model’s clinical utility is not a survey of clinicians’ opinions, but in the measurement of treatment outcomes. A next frontier in this research might be randomly assigning patients and therapists to groups that are either trained to use an alternative dimensional model or conduct PD assessments using the current DSM-IV system. The degree to which either of these groups demonstrated superior treatment outcomes would serve as an indication of incremental clinical utility.

Conclusions

As the field moves toward the next edition of the diagnostic manual, potential revisions should be supported by empirical evidence. The current study provides a replication and extension of previous research assessing how an alternative dimensional model of personality compares to the current DSM-IV PD system in terms of temporal consistency and clinical utility. A group of practicing clinicians described their own patients in terms of the DSM-IV PDs, as well as the FFM, and then rated their utility at the beginning of treatment and again after six months. The results indicated that the FFM ratings evinced moderate temporal consistency, but also indexed important clinical changes. Furthermore, the study also found that the FFM was more clinically useful, both at baseline and after six months of treatment. Taken together, the current findings provide additional evidence for the feasibility of the clinical application of the FFM and suggest that it provides information that enhances clinical decision-making and improves outcomes for individuals with personality pathology.

Finally, the upcoming publication of DSM-5 is almost certain to contain a dimensional trait model. Although it appears the trait model will have notable differences from the FFM (e.g., the presence of six factors, rather than five) there are also substantial similarities. Thus, the current results suggest that the DSM-5 model might also be more clinical useful than the current nomenclature. Similarly, the finding that clinicians’ FFM ratings are reasonably stable across time yet also index important clinical changes, lends support to the clinical application of a future trait model.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by a grant (MH074245) from the National Institute of Mental Health, awarded to the first author. Writing of this manuscript was supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

There are traditionally a number of different terms that might be applicable here including temporal stability or test-retest reliability; however, we chose temporal consistency. We believe that the term “stability” connotes an absence of change, whereas consistency is more neutral (Roberts, Wood, & Caspi, 2008). This is particularly relevant to the current analysis that sampled individuals in active treatment, who might show genuine and meaningful change on scores of personality and personality pathology.

The current data were collected as a part of a larger study concerned with the convergence of the FFM and DSM-IV PDs across various assessment methods (e.g., self-report, semi-structured interview, informant report, and clinician ratings). Interested readers should consult Samuel & Widiger (in press) for further details.

Contributor Information

Douglas B. Samuel, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine

Thomas A. Widiger, Department of Psychology, University of Kentucky

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Rounsaville BJ, Tennen H, Kranzler HR. Reliability of personality disorder symptoms and personality traits in substance-dependent inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:341–352. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais MA. Clinician ratings of the five-factor model of personality and the DSM-IV personality disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1997;185:388–393. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199706000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorder: Perennial issues and an emerging reconceptualization. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:227–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. The NEO personality inventory manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F, Van Leeuwen K, Bagby RM, Rolland JP, Rouillon F. Assessing and interpreting personality change and continuity in patients treated for major depression. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:71–80. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Pincus HA, Levine JB, Williams JBW, Ustun B, Peele R. Clinical utility as a criterion for revising psychiatric diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:946–954. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Stout RL, McGlashan TH. Two-year stability and change in schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:767–775. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Naumann LP, Soto CJ. Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 114–158. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Eaton NR. Personality traits and the classification of mental disorders: toward a more complete integration in DSM-5 and an empirical model of psychopathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2010;1:97–118. doi: 10.1037/a0018990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Skodol AE, Livesley WJ, Shrout PE, Huang Y. Synthesizing dimensional and categorical approaches to personality disorders: Refining the research agenda for DSM-V axis II. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;16:S65–S73. doi: 10.1002/mpr.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe JR, Widiger TA. Clinicians’ judgments of clinical utility: A comparison of the DSM-IV with dimensional models of general personality. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23:211–229. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF, Watson D. Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: An integrative hierarchical approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:139–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser JD, Kaelber C, Weise RD. International use and attitudes toward DSM-III and DSM-III-R: Growing consensus in psychiatric classification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:271–279. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr . The five-factor theory of personality. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Hopwood CJ, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Yen S, McGlashan TH. Comparison of alternative models for personality disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:983–994. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins-Sweatt SN, Widiger TA. Clinicians' judgments of the utility of the DSM-IV and Five-Factor models for personality disordered patients. Journal of Personality Disorders. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.463. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL, Ciarrocchi JW. The utility of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory in an outpatient, drug rehabilitation context. Psychology and Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Wood D, Caspi A. The development of personality traits in adulthood. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 375–398. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Fraley RC, Roberts BW, Trzniewski KH. A longitudinal study of personality change in young adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:617–640. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.694157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottman BM, Ahn W, Sanislow CA, Kim NS. Can clinicians recognize DSM-IV personality disorders from five-factor model descriptions of patient cases. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:427–433. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08070972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. Clinicians’ personality descriptions of prototypic personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:286–308. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.3.286.35446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. Clinicians’ judgments of clinical utility: A comparison of the DSM-IV and five-factor models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:298–308. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1326–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. Comparative gender biases in models of personality disorder. Personality and Mental Health. 2009;3:12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. Comparing personality disorder models: Cross-method assessment of the FFM and DSM-IV-TR. Journal of Personality Disorders. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.6.721. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson CJ, Clarkin JF. Further use of the NEO PI-R personality dimensions in differential treatment planning. In: Costa PT Jr, Widiger TA, editors. Personality disorders and the five factor model of personality. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 351–375. [Google Scholar]

- Soldz S, Budman S, Demby A, Merry J. Personality traits as seen by patients, therapists and other group members: The big five in personality disorder groups. Psychotherapy. 1995;32:678–687. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, First MB, Shedler J, Westen D, Skodol A. Clinical utility of five dimensional systems for personality diagnosis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196:356–374. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181710950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprock J. A comparative study of the dimensions and facets of the Five-Factor Model in the diagnosis of cases of personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;5:402–423. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.5.402.22122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprock J. Dimensional versus categorical classification of prototypic and nonprototypic cases of personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:991–1014. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Durrett CA. Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;Vol. 1:355–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R. Clinical utility of dimensional models for personality pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:283–302. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, Widiger TA. A meta–analysis of the prevalence and usage of personality disorder not otherwise specified (PDNOS) Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:309–319. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.4.309.40350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, Arkowitz-Westen L. Limitations of axis II in diagnosing personality pathology in clinical practice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;155:1767–1771. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Lowe JR. A dimensional model of personality disorder: Proposal for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2008;31:363–378. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Samuel DB. Diagnostic categories or dimensions? A question for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fifth Edition. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:494–504. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Simonsen E. Alternative dimensional models of personality disorder: Finding a common ground. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:110–130. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.2.110.62628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ. Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist. 2007;62:71–83. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ, Clarkin JF, Sanderson C, Costa PT. A description of the DSM-IV personality disorders with the five-factor model of personality. In: Costa PT, Widiger TA, editors. Personality Disorders and the Five Factor Model of Personality. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]