Abstract

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) of the forearm may occur in sports requiring prolonged grip strength. CECS is a function of increasing pressure following muscle expansion within an inelastic tissue envelope resulting in compromise of perfusion and tissue function. Typical symptoms are pain, distal paraesthesia and loss of function. The condition is self-limiting and resolves completely between periods of activity. With no effective medical treatment, the gold standard remains four compartment open fasciotomy (Söderberg, J Bone Joint Surg Br 78(5):780–2, 1996; Wasilewski and Asdourian, Am J Sports Med 19(6):665–7, 1991). Minimally invasive techniques have been described (Croutzet et al., Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 13(3):137–40, 2009) but have a risk of neuro-vascular injury, especially to the ulnar nerve while releasing the deep flexor compartment. We present a safe technique used with six elite rowers for mini-open fasciotomy to minimise scarring and time away from training while reducing the risk of neurovascular injury.

Keywords: Rowing, Muscle injury and inflammation, Chronic exertional compartment syndrome

Introduction

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) of the forearm is a rare but increasingly well recognised condition possibly first described in 1983 [7]. Patients are usually involved in activities with repetitive isometric muscle loading of the wrist while gripping. It has been most reported in competitive motorcycling where it is known as ‘arm pump’ [1, 3], but other sports include gymnastics and hockey [9], wheelchair athletics and climbing [10], water skiing, kayaking and non-sporting activities such as carpentry and manual work [2, 8].

Diagnosis of CECS of the forearm is initially made on a classical symptom history of pain in the forearm, loss of grip strength and altered sensation in the hands brought on by activity. Symptoms must resolve completely between periods of activity and are typically bilateral. Confirmation of the diagnosis is made using intra-compartmental pressure monitoring in multiple compartments before, during and after exercise. Pressure testing in CECS is considered positive if any of the following are found: resting pressure (P) > 15 mmHg, 1 min post-exercise P > 30 mmHg or 5 min post-exercise P > 20 mmHg [5]. More recently, some authors have also suggested accepting a rise of 10 mmHg with exertion regardless of baseline [4].

Anatomy and Physiology

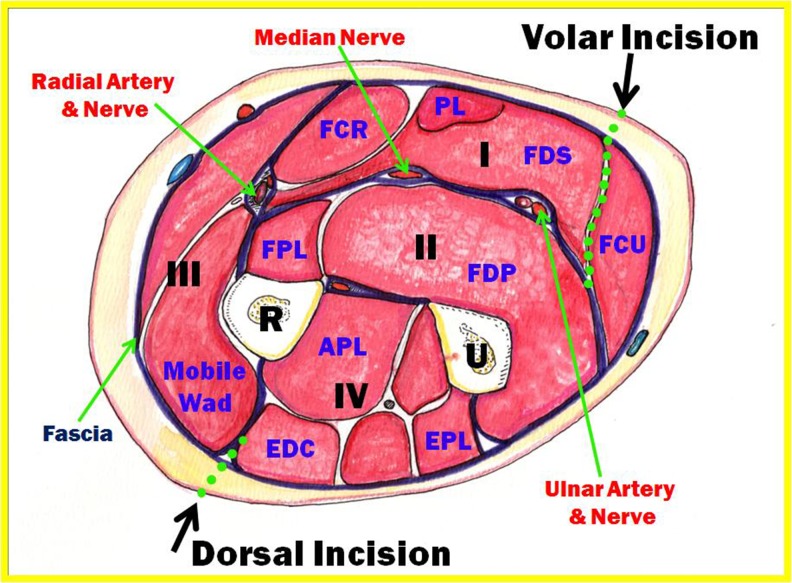

The forearm is divided by the deep fascia into four compartments (Fig. 1) with the superficial (I) and deep (II) flexor compartments and the mobile wad (III) and dorsal (IV) extensor compartments. The extensor compartment is supplied entirely by the posterior interosseous nerve, while the flexor compartment has innervation from the median and ulnar nerves which lie on the deep fascia between the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP). The internervous plane in the superficial flexor compartment is between the FDS and the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU).

Fig. 1.

Division of the forearm into four compartments

CECS results from muscle expansion of up to 20 % during exertion [6] while contained within an inelastic tissue envelope. Early models of the condition have been extrapolated from understanding of acute compartment syndrome which is caused and propagated by accumulation of fluid within the compartment. This fluid expansion is distributed throughout the compartment, and thus, release of the entire length of the compartment is required. In CECS, the muscle bellies are the only expanding element and they are restricted to the proximal two thirds of the forearm. Thus, it is the contention of the authors that only the proximal two thirds of the compartment to the musculotendinous junction needs to be released.

Method

Six elite rowers competing at the national and international levels were referred with features suggestive of CECS of the forearm. All described bilateral symptoms of pain affecting both the flexor and extensor compartments, loss of grip strength and altered sensation in the hands within 2–5 min of commencing full racing pressure or 15–20 min of steady-state rowing with complete resolution at rest. All six were unable to continue with their normal training and were no longer able to compete.

Clinically, all rowers had normal muscle bulk, normal pulses and no evidence of a peripheral nerve entrapment. Diagnosis was confirmed by dynamic compartment pressure monitoring pre- and immediately post-exertion once symptoms had come on in both superficial flexor and dorsal extensor compartments. Under local anaesthetic, the tip of an 18G Venflon was placed in the muscle compartment and then taped to the forearm. This was connected to an arterial line pressure transducer on an anaesthetic trolley. Intracompartment pressures were measured at rest and during exercise with a simple grip strength device sufficient to reproduce their symptoms. All patients underwent bilateral four compartment decompression. They were positioned supine with their arm abducted on an arm table, exsanguinated and tourniquet applied.

Extensor Compartment

A line is marked between the lateral epicondyle and Lister’s tubercle. The line is measured at the junction of the middle and distal thirds. A skin incision is made from 5 cm distal to the epicondyle to 5 cm proximal of the two thirds mark (Fig. 2). This was an average incision of 8 cm. A fasciotomy is performed along the septum between the mobile wad and EDC, thus releasing both extensor compartments. The fascial incisions are extended, once all structures have been identified, both proximally and distally to fully release from the epicondyle to the musculotendinous junction.

Fig. 2.

Extensor and flexor compartments of the forearm

Flexor Compartment

A line is drawn between the medial epicondyle to the junction of the palmaris longus at the distal wrist crease and is marked at two thirds of its length as before. A skin incision is made from 5 cm distal to the epicondyle to 5 cm short of two thirds mark. The fascia is split in line with the incision to release the superficial flexor compartment. The interval between FDS and FCU is developed down to the deep fascia. The ulnar nerve is now clearly visualised and deep fascia is released over FDP taking care to protect the nerve and branches. Again the fascial releases are extended proximally from the epicondyle and distally to the musculotendinous junction.

Results

The diagnosis was confirmed in the first three cases with compartment pressure monitoring. Average readings were 10.4 mmHg volar and 10.8 mmHg dorsal at rest, increasing to 47.3 and 40.4 mmHg, respectively, on exertion (Table 1). In the final three cases, treatment was offered based on a clear clinical history of CECS and invasive monitoring was not felt necessary.

Table 1.

Compartment pressure recordings of first three patients

| Rest | Exercise | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extensor | Flexor | Extensor | Flexor | ||

| Patient 1 | R | 12 | 56 | ||

| L | 30 | 64 | |||

| Patient 2 | R | 9 | 13 | 37 | 40 |

| L | −7 | 12 | 33 | 25 | |

| Patient 3 | R | 12 | 7 | 52 | 75 |

| L | 14 | 9 | 50 | 39 | |

| Mean | 7.0 | 13.8 | 43.0 | 49.8 | |

The first case underwent two separate procedures for the left and right forearms, but the subsequent cases all underwent single stage bilateral four compartment fasciotomy. In all cases, the ulnar nerve was clearly visualised with branches crossing superficial to the fascia, reinforcing the authors concern with a ‘blind’ minimal incision technique.

All six patients returned to full training by 4 weeks post-surgery, and all reported complete resolution of symptoms within 3 months of surgery sufficient to return to competitive rowing. The only complication was a mild sensory ulnar paraesthesia for 1 week post-operation in one rower.

Three of the patients had started rowing through the World Class Start programme. This programme allows talented athletes already competing at an elite level in other sporting disciplines to transfer their skills and undergo an accelerated motor skill acquisition programme to coach them for competitive rowing with the aim of producing elite rowers. Two were members of the British Para Olympic rowing squad. Accolades achieved following surgery include winning the Scottish Universities indoor rowing championships, selections for the 2010 and 2012 U23 World Rowing Championships and members of the Olympic and Para Olympic Rowing Squads 2012.

Discussion

This is the largest series of cases of CECS seen in rowers in the literature. All of the rowers were only symptomatic during periods of higher intensity training or competition. All were unable to continue competing or had noticed their performance worsened at the time of referral. All had made changes to their technique but symptoms had persisted and none were willing to give up the sport. The gold standard of treatment remains an open fasciotomy. Although minimally invasive techniques have been described [3], in the opinion of the authors they pose significant risk to neuro-vascular structures, most notably the ulnar nerve when releasing the deep flexor compartment. This concern was highlighted by the clear visualisation of the nerve and branches during these cases. Our technique aimed to release the fascia over the muscle bellies by performing a fasciotomy of the proximal two thirds of the forearm only and this caused resolution of symptoms in all cases. The shorter incisions allow a rapid return to full training and are more cosmetic (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forearm after the procedure

It is also noted that three of the patients had trained in the World Class Start programme. This intensive training regime is aimed at bringing athletes already proven in other sporting disciplines quickly to Olympic standard in rowing. As most professional sports people have trained since their early teens in a chosen discipline, they possibly have fascial compartments well adapted to the requirements of their sport. We suggest that the rapid increase in muscle bulk after reaching skeletal maturity in an accelerated training programme may have been a causative factor in developing compartment syndrome. This would merit further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Allen MJ, Barnes MR. Chronic compartment syndrome of the flexor muscles in the forearm: a case report. J Hand Surg Br. 1989;14(1):47–8. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(89)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JS, Wheeler PC, Boyd KT, Barnes MR, Allen MJ. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the forearm: a case series of 12 patients treated with fasciotomy. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2011;36(5):413–9. doi: 10.1177/1753193410397900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croutzet P, Chassat R, Masmejean EH. Mini-invasive surgery for chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the forearm: a new technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2009;13(3):137–40. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e3181aa9193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchinson M. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome head to head. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:954–5. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedowitz RA, Hargens AR, Mubarak SJ, Gershuni DH. Modified criteria for the objective diagnosis of chronic compartment syndrome of the leg. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(1):35–40. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rorabeck CH, Macnab I. The pathophysiology of the anterior tibial compartmental syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;113:52–7. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197511000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rydholm U, Werner CO, Ohlin P. Intracompartmental forearm pressure during rest and exercise. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;175:213–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Söderberg TA. Bilateral chronic compartment syndrome in the forearm and the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(5):780–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasilewski SA, Asdourian PL. Bilateral chronic exertional compartment syndromes of forearm in an adolescent athlete. Case report and review of literature. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(6):665–7. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zandi H, Bell S. Results of compartment decompression in chronic forearm compartment syndrome: six case presentations. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(9):e35. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.012518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]