Abstract

We investigated 32 families of persons with acute toxoplasmosis in which >1 other family member was tested for Toxoplasma gondii infection; 18 (56%) families had >1 additional family member with acute infection. Family members of persons with acute toxoplasmosis should be screened for infection, especially pregnant women and immunocompromised persons.

Keywords: acute Toxoplasma infection, United States, families, Toxoplasma, toxoplasmosis, Toxoplasma gondii, parasites, protozoa, acute toxoplasmosis

Only isolated case reports and small case series have been published on acute Toxoplasma gondii. infections among family members (1–6). When a case of acute toxoplasmosis is identified in a family, additional household members might have been infected around the same time period; family members frequently share common exposures to food or environmental sources potentially contaminated with T. gondii. Identification of additional infections could lead to earlier implementation of appropriate interventions for persons in certain high-risk groups, such as immunocompromised persons and pregnant women.

Large-scale evaluation of the prevalence of acute toxoplasmosis among family members in the United States has not been performed (4). Therefore, we investigated the prevalence of acute toxoplasmosis among household and family members of patients who had acute toxoplasmosis.

The Study

We performed a retrospective cohort study using data collected by the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory (PAMF-TSL; www.pamf.org), Palo Alto, California, USA, during 1991–2010. Patient blood samples were sent from diverse laboratories from throughout the United States, and testing was conducted at the PAMF-TSL. The study was approved by the Institutional Research Board at the PAMF Research Institute.

From the PAMF-TSL database, we identified families that 1) had an index case-patient with a diagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis and 2) had >1 additional household/family member who had been tested for T. gondii infection at PAMF-TSL. Details of the process used to identify additional household/family members are described in the Technical Appendix. All identified family/household members were categorized as acutely infected (<6 months before sample collection time); recently infected (6–12 months before sample collection time); chronically infected (>12 months before sample collection time); or never infected. The criteria used for this categorization are described in the Technical Appendix. These criteria are routinely used in the daily clinical practice at PAMF-TSL to estimate the most likely time of the T. gondii infection; the accuracy of these criteria has been previously validated (7–11).

All identified families were categorized in 3 family groups (Technical Appendix). Group 1 consisted of families with an index case-patient who had acute toxoplasmosis and >1 additionally tested family/household member who had acute or recently acquired T. gondii infection. Group 2 consisted of families with an index case-patient who had acute toxoplasmosis; >1 additionally tested family/household member who had chronic T. gondii infection; and no other tested household members who had evidence of acute or recently acquired T. gondii infection. Group 3 consisted of families with an index case-patient who had acute toxoplasmosis and in which no additionally tested family/household members showed evidence of T. gondii infection.

We defined as prevalence of acute T. gondii infection in >1 family members (prevalence of group 1 families) the number of group 1 families divided by the total number of study families over the 20-year study period (primary endpoint). As secondary endpoint, we also calculated the prevalence of group 2 families. We also tested whether the IgG-Dye test titers and IgM-ELISA titers of the index case-patients were different across the 3 family groups by using the Kruskal-Wallis test. All analyses were done in Stata/SE version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

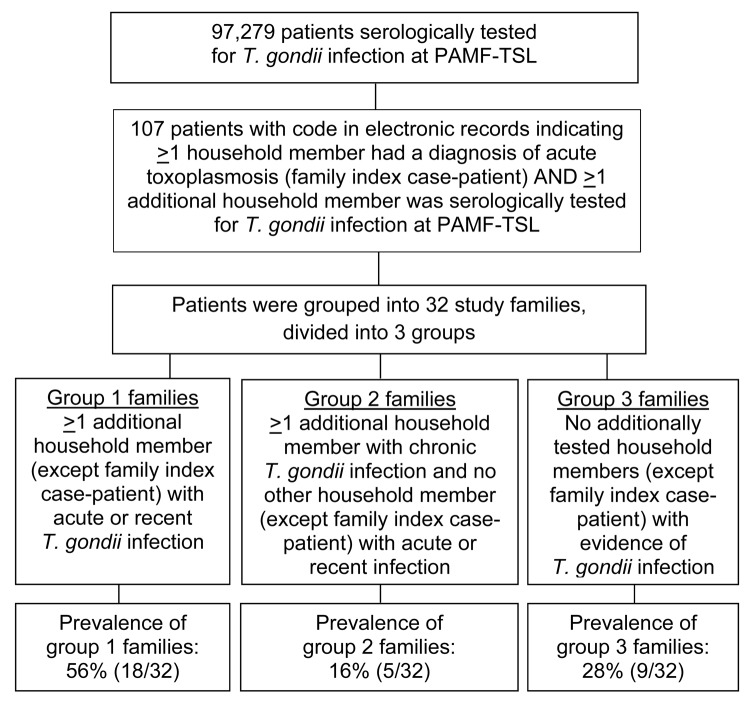

Among 97,279 persons serologically tested for T. gondii in the PAMF-TSL over the 20 year study period, we identified 107 persons who had >1 person from their household with a diagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis and >1 additional household member serologically tested for T. gondii infection. Those 107 persons were grouped into 32 study families (Figure). Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1; serologic test results for members of group 1 families are shown in Table 2, Appendix, and for members of groups 2 and 3 families in the Technical Appendix.

Figure.

Flowchart for the identification of families with an index case-patient who had acute toxoplasmosis and >1 family member with acute or recent Toxoplasma gondii. infection. Data were extracted from the database of the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory (PAMF-TSL; Palo Alto, CA, USA), from patient samples sent to PAMF-TSL during 1991–2010 from laboratories throughout the United States.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical information for persons in the 18 group 1 study families identified from data on acute toxoplasmosis cases collected during 1991–2010 by the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory, Palo Alto, California, USA*.

| IC patient no. | Clinical information for IC | No. additional household members tested | Infection status of additional household members | Clinical information for additional household members | Risk factors reported by ≥1 household member |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC-1 | LN | 2 | Wife: acute infection | Pregnant, first trimester | Ate raw lamb |

| Daughter: no infection | NA | ||||

| (Baby girl: status not ascertained) | |||||

| IC-2 | 8 wks pregnant | 1 | Husband: acute infection | LN | NR |

| (Fetus: AF PCR–) | |||||

| IC-3 | 8 wks pregnant | 1 | Husband: acute infection | Asymptomatic | Contact with cat feces, eating undercooked meat, gardening |

| (Baby boy: could not R/O CT; no follow-up beyond 1 mo of age) | |||||

| IC-4 | 27 wks pregnant | 2 | Husband: acute infection | NA | NR |

| Son: acute infection | NA | ||||

| (Fetus: AF PCR–) | |||||

| IC-5 | 11 wks pregnant | 1 | Husband: acute infection | NA | None |

| (Fetus: AF PCR–) | |||||

| IC-6 | Infant with CT | 2 | (Mother: acute infection) | NA | NR |

| Father: acute infection | NA | ||||

| Brother: acute infection | NA | ||||

| IC-7 | LN, fever, headache | 3 | Wife: acute infection | LN | Poor cleaning of cooking surfaces |

| Daughter 1: acute infection | Posterior cervical LN | ||||

| Household member: chronic infection | NA | ||||

| Son/daughter 2: not tested | |||||

| IC-8 | 13 wks pregnant | 1 | Husband: acute infection | NA | Ate deer meat that had positive results for T. gondii by PCR |

| (Baby Boys A and B: status not ascertained) | |||||

| IC-9 | 22 wks pregnant | 1 | Husband: acute infection | NA | NR |

| (Fetus: NA) | |||||

| IC-10 | Pregnant, third trimester | 2 | Daughter 1: Recent infection | Asymptomatic | Children played in uncovered sandbox |

| Daughter 2: acute infection | Asymptomatic | ||||

| (Baby girl A: asymptomatic; CSF PCR–, could not R/O CT; baby girl-B: CT, macular scar, ascites, AF PCR+, CSF PCR+) | |||||

| IC-11 | Infant with CT† | 2 | (Mother: recent infection) | NA | NR |

| Father: recent infection | NA | ||||

| Sister: no infection | NA | ||||

| IC-12 | LN, fever, hepatitis | 3 | Wife: acute infection | LN | Ate raw lamb |

| Household member 1: acute infection | LN | ||||

| Household member 2: acute infection | NA | ||||

| IC-13 | 21 wks pregnant | 1 | Husband: acute infection | LN | Ate venison tartare |

| (Fetus: CT, ascites, hydrocephalus; abortion) | |||||

| IC-14 | Infant with CT | 1 | (Mother: acute infection) | NA | Ate bear meat; ate deer meat that had positive results for T. gondii by PCR |

| Father: acute infection | Fever, flu-like symptoms | ||||

| IC-15 | 9 wks pregnant | 1 | Husband: acute infection | NA | None |

| (Baby boy: status not ascertained) | |||||

| IC-16 | Febrile illness (fibromyalgia)‡ | 3 | Daughter 1: Recent infection | NA | Ate deer meat that had positive results for T. gondii by PCR |

| Daughter 2: no infection | NA | ||||

| Grandson: no infection | NA | ||||

| IC-17 | Eye disease | 3 | Son: acute infection | NA | NR |

| Daughter 1: acute infection | Asymptomatic | ||||

| Daughter 2: no infection | NA | ||||

| IC-18 | LN | 1 | Wife: Recent infection | NA | NR |

*Mother-infant pairs were counted as 1 unit/household member; infection status of these is shown in parenthesis. IC, index case-patient; LN, lymphadenopathy; NA, not available; NR, not reported; AF, amniotic fluid; R/O, rule out; CT, congenital toxoplasmosis; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid. †Infant with CT with hydrocephalus, high bilirubin, abnormal liver function tests, low platelets, and positive PCR results on CSF. ‡Female patient taking chronic corticosteroids; patient died.

Table 2. Serologic test results for family index case-patients and additionally tested household members in the 18 group 1 study families*.

| Index case-patients (clinical information) and additional household members tested | IgG by dye test | ELISA results |

AC/HS pattern | Avidity | Interpretation of infection type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgA | IgE | |||||

| IC-1 (LN) | 512 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 3.1 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Wife† | 4,096 | 3.2 | 10.3 | 1.1 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Daughter | <16 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0 | Nonreactive | ND | None |

| Baby girl | 2,048 | 0 (ISAGA) | 2 | 0.2 | ND | ND | Status NA |

| IC-2 (8 wks pregnant) | 8,000 | 5.7 | 13.9 | 2.6 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Husband | 16,000 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Fetus | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Status NA |

| IC-3 (8 wks pregnant) | 16,000 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 1.1 | Acute | Low (7.8) | Acute |

| Husband | 8,000 | 7.3 | >11 | 2.4 | Acute | Low (4.4) | Acute |

| Baby boy | 2,048 | 0 (ISAGA) | 0 | ND | ND | ND | Status NA |

| IC-4 (27 wks pregnant) | 512 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 0.4 | Equivocal | Low (2.8) | Acute |

| Husband | 1,024 | 5.9 | 12.4 | Negative | Acute | Low (5.4) | Acute |

| Son | 16,000 | 7.2 | >24 | 4.2 | Acute | Low (10.5) | Acute |

| Fetus | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Status NA |

| IC-5 (11 wks pregnant) | 2,048 | 5.8 | 2 | 0.2 | Acute | Low (6.7) | Acute |

| Husband | 1,024 | 5.8 | 2.3 | 0 | Acute | Low (13.2) | Acute |

| Fetus | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | AF PCR– |

| IC-6 (infant with CT) | 32,000 | 12 (ISAGA) | >24 | 9.5 | ND | ND | Congenital |

| Mother | 32,000 | 10.5 | >24 | 4.6 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Father | 8,000 | 4.9 | 11 | 1.1 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Brother | 2,048 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 0.2 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| IC-7 (LN, fever, headache) | 8,000 | 9.9 | >11.2 | >20 | Acute | Low (1.3) | Acute |

| Wife | 32,000 | 5.2 | 9.4 | 1.3 | Acute | Low (1.0) | Acute |

| Daughter 1 | 1,024 | >10.0 | 7.2 | 5.3 | Acute | Low (1.2) | Acute |

| Household member | 512 | 0.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | Chronic |

| IC-8 (13 wks pregnant) | 512 | 7.9 | 5.7 | ND | Acute | Low (7.4) | Acute |

| Husband | 4,096 | 7.2 | 1.8 | 1.9 | Acute | Low (11.0) | Acute |

| Baby boy A | 1,024 | 0 (ISAGA) | 0.2 | ND | ND | ND | Status NA |

| Baby boy B | 1,024 | 0 (ISAGA) | 0 | ND | ND | ND | Status NA |

| IC-9 (22 wks pregnant) | 2,048 | 7.8 | 1.3 | 0.8 | Acute | Low (1.8) | Acute |

| Husband | 4,096 | 9.8 | 6.4 | 3.9 | Acute | Low (6.6) | Acute |

| IC-10 (pregnant, third trimester) | 4,096 | 5.4 | 9.4 | 2.9 | Acute | Low (5.9) | Acute |

| Baby girl A | 8,000 | 0 (ISAGA) | 0.9 | 0.8 | ND | ND | Status NA |

| Baby girl B | 8,000 | 7 (ISAGA) | 1.6 | 0.3 | ND | ND | Congenital |

| Daughter 1 | 8,000 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.2 | Equivocal | Low (12.5) | Recent |

| Daughter 2 | 8,000 | 0.7 | >11.2 | 1.5 | Acute | Low (15.9) | Acute |

| IC-11 (infant with CT) | 8,000 | 12 (ISAGA) | 4.4 | ND | ND | ND | Congenital |

| Mother | 8,000 | 2.7 | ND | ND | Acute | ND | Recent |

| Father | 8,000 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | Acute | Low (16.2) | Recent |

| Sister | <16 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | None |

| IC-12 (LN) | 4,096 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 14.1 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Wife | 8,000 | >10.0 | 11.2 | >14.0 | Acute | Low (3.8) | Acute |

| Household member 1 | 8,000 | >10.0 | >20.0 | >14.0 | Acute | Low (2.4) | Acute |

| Household member 2 | 1,024 | >10.0 | 10.2 | 14.9 | Acute | Low (11.5) | Acute |

| IC-13 (21 wks pregnant; abortion) | 1,024 | 8.3 | 0.7 | ND | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Husband | 4,096 | 8.6 | 6.5 | ND | Acute | ND | Acute |

| IC-14 (infant with CT) | 32,000 | 7 (ISAGA) | >11.2 | ND | ND | ND | Congenital |

| Mother | 8,000 | 5.6 | >11.2 | 4.4 | ND | Low (15.7) | Acute |

| Father | 8,000 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 1.4 | Acute | Low (16.3) | Acute |

| IC-15 (9 wks pregnant) | 2,048 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 3.1 | Equivocal | Low (4.3) | Acute |

| Husband | 128 | 5.2 | 0.4 | 0.8 | Equivocal | Low (8.0) | Acute |

| Baby boy | 256 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | Status NA |

| IC-16 (fibromyalgia; taking steroids; fever; patient died) | 8,000 | 9.4 | 4.5 | 11 | Acute | Low (0.7) | Acute |

| Daughter 1 | 2,048 | 3.2 | 3.8 | ND | Equivocal | Low (4.6) | Recent |

| Grandson | <16 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | None |

| Daughter 2 | <16 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | None |

| IC-17 (eye disease) | 2,048 | 8.1 | 3.4 | 10 | Acute | Low (6.8) | Acute |

| Son | 32,000 | 9.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | Acute |

| Daughter 1 | 128,000 | 8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | Acute |

| Daughter 2 | <16 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | None |

| IC-18 (LN) | 2,048 | 8.8 | 3.2 | 7.1 | Acute | ND | Acute |

| Wife | 1,024 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | Acute | ND | Recent |

*Mother-infant pairs were counted as 1 unit/household member. Interpretation of results: IgG dye test, positive >16, negative <16; IgM ELISA, positive >2.0, equivocal 1.7–1.9, negative <1.6; IgM ISAGA (for infants <6 mo of age), positive 3–12, negative 0–2; IgA ELISA, positive >2.1, equivocal 1.5–2.0, negative ≤1.4; IgE ELISA, positive >1.9, equivocal 1.5–1.8, negative <1.4; avidity, low <20, equivocal 20–30, high >30. The categorization of AC/HS test results into acute, equivocal, and nonreactive is available at www.pamf.org/serology/images/achs_grid.html. AC/HS, differential agglutination; IC, index case-patient; LN, lymphadenopathy; ND, not done; ISAGA, immunosorbent agglutination assay; NA, not ascertained; AF, amniotic fluid; CT, congenital toxoplasmosis. Serologic test results, despite equivocal AC/HS, were consistent with acute infection in IC4 and IC15 and recent infection in daughter 1 of IC10 and IC16. †Pregnant woman who was serologically tested for toxoplasmosis because of her husband’s toxoplasmic lymphadenitis.

The prevalence of group 1 families in our study was 56% (18/32); group 2 families, 16% (5/32); and group 3 families, 28% (9/32) (Figure). The IgG-Dye test and the IgM-ELISA titers of the index case-patients were not significantly different across the 3 family groups (p = 0.27 for IgG and p = 0.07 for IgM) (Table 2, Appendix; Technical Appendix). For group 1 families, all additional family members with acute/recently acquired infection had serologic profiles (titers of IgG, IgM, and/or IgA/IgE and avidity) that were similar to those of the index case-patients, indicating that they were infected at about the same time (Table 2, Appendix).

Conclusions

Our data provide preliminary evidence that multiple cases of acute T. gondii infection may occur among family/household members. These findings are particularly critical for persons at high risk from T. gondii infection, such as women who are or may become pregnant or immunocompromised persons. Interpretation of our study findings would have been clearer had the background prevalence of acute toxoplasmosis in the United States been known. Although no such population-level empirical data exist, we have identified at PAMF-TSL 889 patients with acute T. gondii infection over the 20-year study period (estimated prevalence ≈9/1,000 patients screened at PAMF-TSL; unpub. data).

A limitation of our study is that the families tested at PAMF-TSL over this study period might represent a group in whom the prevalence of acute T. gondii infection in >1 family member has been overestimated. Only 4% of persons who had acute toxoplasmosis diagnosed at PAMF-TSL during the 20-year study period had samples sent from additional household members for T. gondii testing (32 index case-patients with acute toxoplasmosis/889 acute infections). The collection of those additional samples depended solely on the response of the referring physicians to a 1-time written request for testing of additional family members. It is possible that the response of the primary care providers to this request would have been more likely if any of those additional family/household members had symptoms suggestive of acute toxoplasmosis. In addition, the IgG-Dye test and IgM-ELISA titers of the index case-patients did not predict which families would have additional household members with acute toxoplasmosis.

Further replication of the estimated prevalence of acute T. gondii infection in consecutive US families is needed. Future studies might also compare the T. gondii serotypes among index case-patients and family members (type II vs. non–type II) (12), which could help clarify whether certain serotypes are more likely to be associated with family outbreaks. Moreover, it would be useful to screen for antibodies to sporozoite-specific antigens (13), which can provide further insight regarding the source of T. gondii infection that is more likely to be associated with acute toxoplasmosis in >1 family member (e.g., sporozoite-specific, related to contact with cat feces, vs. bradyzoite-specific, related to ingestion of undercooked meat [14]).

When a case of acute toxoplasmosis is diagnosed, screening of additional family members should be considered, especially if pregnant women or immunocompromised patients live in those households, so that appropriate preventive strategies and/or therapeutic interventions are applied. These within-family clusters of cases are not easy to predict based solely on clinical or epidemiologic information, except for situations of sharing common meal (i.e., with undercooked meat), because it is unlikely that other risk factors would be different. Thus, only routine serologic screening of household members of acutely infected persons might identify such acute T. gondii infections.

Supplementary methods and results from study of families of persons with acute toxoplasmosis using data collected in the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory, Palo Alto, California, USA, from patient samples sent to PAMF-TSL during 1991–2010 from laboratories throughout the United States.

Acknowledgments

We thank Catalina-Angel Malkun for help collecting hard copies of the patients’ records and with data extraction.

Biography

Dr Contopoulos-Ioannidis is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Infectious Diseases, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; and Medical Consultant at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory, Palo Alto, CA. Her research interests include epidemiology of toxoplasmosis, laboratory diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis, pediatric infectious diseases, comparative effectiveness research, evidence-based medicine, and outcome research.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Maldonado Y, Montoya JG. Acute Toxoplasma gondii infection among family members in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 Dec [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1912.121892

References

- 1.Masur H, Jones TC, Lempert JA, Cherubini TD. Outbreak of toxoplasmosis in a family and documentation of acquired retinochoroiditis. Am J Med. 1978;64:396–402 . 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90218-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stagno S, Dykes AC, Amos CS, Head RA, Juranek DD, Walls K. An outbreak of toxoplasmosis linked to cats. Pediatrics. 1980;65:706–12 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacks JJ, Roberto RR, Brooks NF. Toxoplasmosis infection associated with raw goat’s milk. JAMA. 1982;248:1728–32 . 10.1001/jama.1982.03330140038029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luft BJ, Remington JS. Acute Toxoplasma infection among family members of patients with acute lymphadenopathic toxoplasmosis. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:53–6 . 10.1001/archinte.1984.00350130059012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coutinho SG, Leite MA, Amendoeira MR, Marzochi MC. Concomitant cases of acquired toxoplasmosis in children of a single family: evidence of reinfection. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:30–3 . 10.1093/infdis/146.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silveira C, Belfort R Jr, Burnier M Jr, Nussenblatt R. Acquired toxoplasmic infection as the cause of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis in families. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:362–4 . 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90382-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dannemann BR, Vaughan WC, Thulliez P, Remington JS. Differential agglutination test for diagnosis of recently acquired infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1928–33 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montoya JG, Huffman HB, Remington JS. Evaluation of the immunoglobulin G avidity test for diagnosis of toxoplasmic lymphadenopathy. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4627–31. 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4627-4631.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montoya JG. Laboratory diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection and toxoplasmosis. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(Suppl 1):S73–82. 10.1086/338827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montoya JG, Remington JS. Studies on the serodiagnosis of toxoplasmic lymphadenitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:781–9. 10.1093/clinids/20.4.781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montoya JG, Berry A, Rosso F, Remington JS. The differential agglutination test as a diagnostic aid in cases of toxoplasmic lymphadenitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1463–8. 10.1128/JCM.01781-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong JT, Grigg ME, Uyetake L, Parmley S, Boothroyd JC. Serotyping of Toxoplasma gondii infections in humans using synthetic peptides. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1484–95. 10.1086/374647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill D, Coss C, Dubey JP, Wroblewski K, Sautter M, Hosten T, et al. Identification of a sporozoite-specific antigen from Toxoplasma gondii. J Parasitol. 2011;97:328–37. 10.1645/GE-2782.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubey JP, Rajendran C, Ferreira LR, Martins J, Kwok OC, Hill DE, et al. High prevalence and genotypes of Toxoplasma gondii isolated from goats, from a retail meat store, destined for human consumption in the USA. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:827–33 . 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary methods and results from study of families of persons with acute toxoplasmosis using data collected in the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Toxoplasma Serology Laboratory, Palo Alto, California, USA, from patient samples sent to PAMF-TSL during 1991–2010 from laboratories throughout the United States.