Abstract

Respondent-driven sampling (RDS) is a method for recruiting “hidden” populations through a network-based, chain and peer referral process. RDS recruits hidden populations more effectively than other sampling methods and promises to generate unbiased estimates of their characteristics. RDS’s faithful representation of hidden populations relies on the validity of core assumptions regarding the unobserved referral process. With empirical recruitment data from an RDS study of female sex workers (FSWs) in Shanghai, we assess the RDS assumption that participants recruit nonpreferentially from among their network alters. We also present a bootstrap method for constructing the confidence intervals around RDS estimates. This approach uniquely incorporates real-world features of the population under study (e.g., the sample’s observed branching structure). We then extend this approach to approximate the distribution of RDS estimates under various peer recruitment scenarios consistent with the data as a means to quantify the impact of recruitment bias and of rejection bias on the RDS estimates. We find that the hierarchical social organization of FSWs leads to recruitment biases by constraining RDS recruitment across social classes and introducing bias in the RDS estimates.

Keywords: Respondent Driven Sampling, hidden populations, recruitment bias, sex workers, HIV, China

Populations are “hidden” or “hard-to-reach” if they are too small to show up in standard probability sampling designs and/or are defined with reference to characteristics and behaviors that are socially stigmatized and/or illegal. The latter concerns apply to groups who are resistant to or uncooperative with data collection efforts because of fear of retaliation (e.g., low wage workers), repatriation (e.g., illegal immigrants), adversarial relations with law enforcement agencies (e.g., homeless people), or increased privacy concerns in some cultural and social settings (e.g., gay and lesbian populations). Many population groups who are especially vulnerable to acquiring and transmitting HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) share both attributes: They are not easily identifiable and they represent a small fraction of the population. These include female sex workers (FSWs), injecting drug users (IDUs), and men who have sex with men (MSM). The extent of HIV risk within these populations and the impact on the health dynamics of the larger population are difficult to discern, however, since traditional observational schemas—from direct observation to clinic-based inquiries to snowball sampling—lack a basis for inferring representation.

Respondent-driven sampling (RDS; Heckathorn 1997; Heckathorn et al. 2002) is an approach that seeks to provide a probability-based inferential structure for representations of hidden populations that would otherwise be elusive to researchers under traditional probability sampling approaches. This approach capitalizes on the network structure of hidden populations to identify, recruit, and interview subjects (Salganik 2006; Salganik and Heckathorn 2004). However, confidence in the ability of RDS to generate valid estimates of population characteristics is complicated by the fact that one does not know the relationship between the RDS sample and the true population values. The validity of RDS population estimates rests on several core assumptions regarding the unobserved referral process of participants to other participants and, more generally, the process of recruitment of potential respondents into the sample. These assumptions have rarely been empirically evaluated. Here we evaluate whether one of RDS’ core assumptions, the nonpreferential recruitment assumption, is met among an RDS sample of FSWs in China. We use data that track recruitment behaviors of RDS participants in order to (a) explore recruitment behaviors in selecting alters for referral; (b) identify the types of bias in recruitment inconsistent with the nonpreferential recruitment assumption required by RDS theory; (c) explore whether the repertoire of the relationship between recruiters and their network alters influences the probability of potential respondents being recruited into the sample; and (d) quantify the impact of respondent referral behavior on RDS estimates of population characteristics.

Respondent-driven Sampling

In RDS, the target for representation is the hidden population of a well-defined geographic area (e.g., a city). RDS starts by recruiting respondents through a chain referral approach initiated by the researcher’s selection of a limited number of “seed” respondents belonging to the population of interest. Seeds are interviewed and given a limited number of invitational coupons which they are asked to distribute to their immediate social contacts in the target population. Members of the seeds’ social circles who receive coupons and choose to participate in the study form the first “wave” of the sample. This process proceeds recursively (hence the term “chain referral”) through multiple waves of recruitment until a desired sample size is reached.

RDS has proven effective for recruiting hidden population samples because it is inclusive and efficient. Compared to methods such as venue-based sampling, time-location sampling and convenience sampling implemented among IDUs in the United States (Robinson et al. 2006), MSMs in Brazil (Kendall et al. 2008), MSMs in China (He et al. 2008), and FSWs in Vietnam (Johnston et al. 2006) and China (Weir et al. 2012), RDS demonstrated several advantages: (1) it was able to reach enhanced coverage of the hard-to-reach pockets of the population of interest; (2) it encouraged study participation by exploiting social ties within the target population; and (3) it efficiently and cost-effectively recruited large numbers of survey respondents in a relatively short amount of time.

RDS’s relative ease of recruiting study participants comes at the cost of making two related assumptions about its sampling process: (1) all members of the target population can, in principle, be reached through the chain referral process, and (2) sample inclusion probabilities are exactly proportional to respondents’ reported personal network sizes, equivalent to the target population they know. Heretofore, we refer to this assumption as “Sampling Probability Proportional to Degree” (SPPD).

The extant RDS theory treats the sample as if it were selected by an unequal probability sampling design in which approximated inclusion probabilities are used to compute sampling weights. These weights are used in place of exactly known inclusion probabilities (Volz and Heckathorn 2008). In unequal probability sampling, members of the target population are selected with different but known-to-researchers inclusion probabilities which are used as the basis for computing sampling weights. If each respondent is labeled by i ranging from 1 to n (the sample size), then we can write the sample inclusion probability for the ith respondent as πi, and the sampling weight as 1/πi. The argument behind this approach is that the characteristics of the oversampled individuals (i.e., those with high values of πi) should be down-weighted when computing population averages. If yi is the observed value of a trait (either continuous or binary) for the ith respondent, the population mean (or proportion) of this trait is estimated using the (generalized) Horvitz-Thompson estimator (Thompson 2002):

To approximate inclusion probabilities, the RDS estimation procedures rely on a two-step approach. First, since the chain referral process will most likely select members of the population who have more social ties, one must assume that the inclusion probability of a sample unit is exactly proportional to the number of reciprocal ties she has with other members of the target population (also referred to as personal network size or as degree in graph theory terminology). Second, in order to assess each respondent’s degree, respondents are asked to report the number of people they know in the target population. The two most commonly used RDS estimators rely on the SPPD assumption to make population proportion estimates (Salganik and Hechathorn 2004; Volz and Heckathorn 2008).

In our assessment of RDS assumptions, we use the Volz-Heckathorn (V-H) estimator (Volz and Heckathorn 2008) because simulations and empirical studies have found that it yields estimates with less bias (Gile and Handcock 2010; Tomas and Gile 2011; Volz and Heckathorn 2008; Wejnert 2009) than the more conventionally used Salganik-Heckathorn (S-H) estimator used in the Respondent Driven Sampling Analysis Tool (RDSAT; Volz et al. 2007). An additional advantage is that the V-H estimator can be used with both categorical and continuous variables.

While the S-H estimator also accounts for cross-group recruitment patterns, the V-H estimator only requires the SPPD assumption to make group proportion estimates by substituting reported degrees for inclusion probabilities as follows (Volz and Heckathorn 2008):

where di is the ith respondent’s self-reported degree. Provided that the SPPD is correct, the V-H estimator is exactly equal to the Horvitz-Thompson estimator and it is a standard result from the theory of unequal probability sampling that this estimator will provide an asymptotically unbiased estimate of the population mean (Thompson 2002). Thus, the estimator attempts to compensate for what may be the tendency of RDS’s chain referral strategy to oversample individuals with large personal social networks by weighting these cases down.

The SPPD assumption underlying the V-H estimator rests on an idealized model of how sample subjects make referrals to new subjects and potential respondents are recruited into the sample. Specifically one must assume: (a) equal probability that a respondent, already contacted, will refer any of the individuals from her immediate social network (the nonpreferential recruitment assumption); (b) reciprocity (the social ties between recruiters and their recruits are symmetric, i.e., if individual a recruits b, then b would recruit a); (c) accurate self-report of how many members of the target population the recruiters know; (d) the network must be sufficiently large that the sample fraction remains small.

If any of these assumptions (a)–(d) are not met, the RDS estimators will likely generate biased estimates of characteristics of the target population. Previous evaluations of RDS have quantified, with simulations, the effect of deviations from assumptions (a)–(d) on the RDS estimators (Gile and Hand-cock 2010; Neely 2009). A handful of studies have empirically investigated the RDS assumptions about the unobserved social network on populations with known characteristics (McCreesh et al. 2012; Wejnert 2009; Wejnert and Heckathorn 2008), with simulation on real-world network data sets (Goel and Salganik 2010) and with limited information on participants’ recruitment behavior (Iguchi et al. 2009). Collectively, these studies have shown that (1) violation of the characteristics of the underlying network and referral process assumptions can lead to considerable bias in the RDS estimates (Gile and Handcock 2010; Lu et al. 2011; Iguchi et al. 2009; McCreesh et al. 2012; Neely 2009; Wejnert 2009); and (2) the structure of real-world social networks may deviate so much from the idealized model assumed by RDS that the variance in population estimates may require sample sizes nearly 10 times that of what has previously been assumed (Goel and Salganik 2010).

A crucial feature of the RDS approach which may interfere with the ability of RDS to produce representative samples is that researchers generally lack knowledge and control of respondents’ referral behavior and of how members of the hidden population are recruited into the sample. Empirical studies of real-world populations recruited with RDS have found evidence of violation of the nonpreferential recruitment assumption. These studies have compared the composition of respondents’ networks, elicited from respondents’ self-reports about the characteristics of their network alters, to their actual recruitment patterns. Iguchi et al. (2009) used IDU respondents’ reports on the gender composition of their entire networks to calculate what recruitments would have been had participants recruited in a manner consistent with their self-reported network composition. Comparison of these expected recruitments with actual recruitments revealed that both men and women overrecruited peers of their own gender leading to upward-biased (S-H) estimates of group proportions. These findings are consistent with those of Wejnert and Heckathorn (2008) in a web-based RDS study of college students, where men and Asian Americans demonstrated preference for recruiting peers of their own gender and racial group. McCreesh et al. (2012) evaluated the performance of RDS in a nonhidden population of Ugandan villagers and documented evidence of respondents’ preferential recruitment by age, tribe, socioeconomic status, village, and sexual activity. The complex nature of the RDS recruitment process suggests that the collection and analyses of data on respondents’ referral behaviors can shed light on factors that may influence whether or not members of the population are included in the sample and whether these lead to biases in RDS estimates of population characteristics. In this article, we describe recruitment behaviors in the context of an RDS study of FSWs in China and assess their impact on RDS estimates using uniquely collected recruitment data. This assessment is meaningful because sex work in China is organized around a semirigid social hierarchy of tiers or classes that are demarcated by social differences. This hierarchical structure may reduce social interactions between sex workers in different tiers leading to socially directed recruitments and potentially biased RDS estimates. The implications of this structure for cross group recruitments deserve close attention because this hierarchical structure is a common feature of the organization of FSWs in Asia (Lim 1998) among whom RDS studies are routinely conducted (Blankenship et al. 2008; Johnston et al. 2006).

We first describe the structure of sex work in China and evaluate whether it interferes with the conditions of sample recruitment required by RDS. We identify sources of recruitment bias (i.e., a respondent is more likely to invite social contacts from one particular group than if she were recruiting at random from among her social contacts) or of rejection bias (i.e., social contacts affiliated with a particular group are more or less likely to refuse the invitation to participate) between and among sex workers in three different tiers of sex work. Similar to Iguchi et al (2009), our assessment relies on the collection and comparison of the attributes of three types of network alters identified by RDS respondents’ self-reports: (1) network alters who were invited and accepted the invitation to participate, (2) network alters who were invited but refused the invitation to participate, and (3) alters who are members of respondents’ networks but who were not invited to participate. We further explore possible reasons for recruitment and rejection biases using data that characterize the relationship between respondents and their network alters.

To enhance our substantive conclusions, we also present a bootstrap methodology for constructing confidence intervals around RDS V-H estimates. This method is a variant of the bootstrap methodology presented in Salganik (2006) for the S-H estimator used in RDSAT. We extend this methodology to assess the impact on the RDS estimates of different network structures consistent with actual recruitment patterns, invited recruitment patterns, and recruitment patterns expected under nonpreferential recruitment.

Sampling FSWs in China

FSWs play a crucial role in the progression of HIV and other STDs in China by acting as bridges of infection to the general population (Merli et al. 2006; Pirkle, Soundardjee, and Artuso 2007). The recruitment of samples that adequately represent the FSW population is important for describing variation in sex workers’ behavioral characteristics and infection status, identifying their contribution to the recent spread of HIV/STDs in the general population (Chen et al. 2007; Tucker, Chen, and Peeling 2010; Wang et al. 2010), and designing and implementing effective HIV/STD prevention and control programs.

Recruiting representative samples of FSWs in China is complicated by two factors: (1) sex work is illegal and socially stigmatized and (2) FSWs are socially organized according to a descending hierarchy of classes or tiers which are not all equally accessible to health workers and researchers. Tier of sex work is defined according to the types of locations where sex workers solicit clients and provide sexual services, the price they charge per sexual transaction and the socioeconomic background of their clients (Hershatter 1997; Huang et al. 2004; Lim 1998; Parish and Pan 2006; Rogers et al. 2002; Xia and Yang 2005). Solicitation of sex for money in China is largely mediated through China’s new and burgeoning commercial recreational business sector. High-tier sex workers solicit clients by phoning rooms in good hotels or are the female staff of karaoke or dance halls. These halls employ a large number of women who accompany customers in singing, dancing, and drinking and can provide sexual services for additional compensation. Middle-tier sex workers are the female staff of smaller establishments that offer commercial sex under the guise of personal services such as bathing and massage, hair washing, beauty services, and foot cleaning/massage. Low-tier sex workers solicit clients directly on the streets, in parks or other public spaces, or on construction sites in return for small amounts of money. Because their activities are not mediated by the recreational business sector, they are more visible and vulnerable to police raids. They are often resistant to being recruited into studies for fear of being identified.

In late 2007, we used RDS to recruit a sample of FSWs in Shanghai for the Shanghai Women’s Health Survey, a study of sexual behavior and STDs among FSWs residing in Shanghai. We chose to implement RDS for three reasons. First, alternative sampling designs of FSWs were limited by sampling frames that covered the more reachable, visible segments of the population, including women working in massage parlors and hair salons whose owners curry favor with disease prevention officials by providing access to the sex workers (Huang et al. 2004; Lin et al. 2008; Pan 1997); institutional lists of women attending STD clinics; and women registered in “re-education” centers (Gil et al. 1996; Lau et al. 2002). Studies that used peer referral techniques (e.g., snowball sampling) alone or in combination with venue-based sampling were more successful at reaching broadly across tiers of FSWs (Ding et al. 2005; Lu et al. 2009; Ruan et al. 2006). Second, previous studies concluded that RDS was successful in quickly and efficiently recruiting large, diverse samples of FSWs in Vietnam (Johnston et al. 2006) and in India (Blankenship et al. 2008).1 Third, formative research suggested that FSWs in Shanghai could accommodate the RDS chain referral process because they did not display traits that are known to limit the adequacy of RDS. Populations inadequate for RDS include those in which members of the population engage in little social interaction with each other (e.g., tax evaders), are highly segmented along geographic lines, or are socially prohibited from interacting with each other (e.g., a caste system). It has been suggested that the presence of such traits could trap the chain referral process in a particular subgroup (Heckathorn and Jeffri 2005; Wejnert and Heckathorn 2008), preventing potential recruitment of members of other subgroups into the sample. However, it is not known whether the structure of a socially ordered population, such as FSWs in Shanghai, would interfere with the referral process in ways that compromise the SPPD assumption and the validity of RDS estimates.

Data

Sample

The Shanghai RDS study was conducted over the course of three months between September and December 2007. Eligibility for participation in the study was being 18 years old, a first time participant and self-identifying as an FSW by responding affirmatively to the question: “Have you exchanged sex for money in the past month?” Seven seeds and 515 peer recruits were interviewed. Of the seven seeds, one did not recruit any participants and the other generated only one referral wave. The remaining five seeds each generated at least six waves with a maximum of 11 waves generated by two seeds. The total sample size of 522 exceeded the target sample size of 454 calculated based on a Chlamydia prevalence rate of 18 percent, a design effect of 2 recommended by studies on size calculation for RDS samples (Salganik 2006) and a desired level of statistical significance of α = .05 (two-sided).

Participants were interviewed in two fixed interview sites that were located in two of the nine Shanghai city center districts, where about 40 percent of the 19 million people living in Shanghai’s 19 districts are concentrated. Both sites were easy to reach by public transportation. In all, 255 participants were interviewed in a center city district abutting the northern city suburbs and 267 were interviewed near the southern city suburbs. Participants interviewed at the two sites were viewed as contributing to one single sample and data from the two sites were analyzed together. We mapped the nearest street corner to the places where participants reported soliciting clients. The map revealed that participants recruited from the northern site were not more likely to recruit sex workers from neighborhoods close to the interview sites than participants recruited from the southern site. In fact, there was frequent cross-recruitment among neighborhoods adjacent to either site.

The study began by distributing three coupons to each participant, a number which, according to standard RDS protocol, ensures the continuation of the recruitment chains despite unsuccessful recruitments. Once recruitment of respondents had taken off and we had established that the chain referral process was sustainable, we reduced the number of coupons to two in the fifth wave and from two to one in the seventh and all subsequent waves. The idea of systematic coupon reduction was discussed by Johnston et al. (2008). Our decision to reduce the number of coupons for sample growth control and to increase the length of recruitment chains was taken before the publication of that study. It was based on the theoretical consideration that this forces the sampling process to more closely resemble a nonbranching random walk. Gradual reduction of the number of coupons from three to two to one has the advantage of reducing the dependence between sample units, hence the variance of the RDS estimates (Goel and Salganik 2009), while simultaneously ensuring continuation of the recruitment chains until the target sample size is reached.

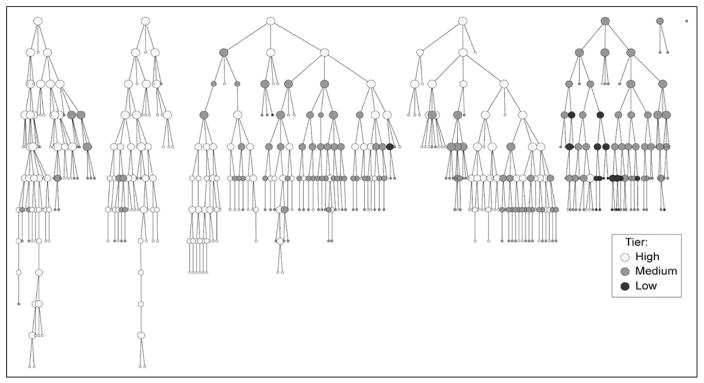

Figure 1 shows the recruitment trees of each seed (seeds at top, waves descending from the top). Recruiting participants have edges (recruitment links) emanating down the tree. The size of the node (the participant) is proportional to the number of participants she recruited. Each of the 271 recruiting participants recruited an average of 1.9 alters. There were 251 nonrecruiting participants who are the terminal nodes at the end of the tree branches.

Figure 1.

Observed recruitment chains. Seeds at top size, proportional to number directly recruited.

Each respondent received a primary incentive of 100 renminbi (RMB; about US$14) for the interview, a secondary incentive of 80 RMB for each of her successful recruitments, and a smaller amount (30 RMB) to cover the cost of transportation to the interview sites. The size of these incentives was determined in consultation with Shanghai health outreach workers, and they were not too high so they would not be coercive. The study also encouraged participation as a means to health promotion. Participants were given basic reproductive health counseling by trained nurses/interviewers and were invited to provide a urine sample for assays of Chlamydia and gonorrhea. If they tested positive, they were referred to the local STD hospital for treatment. All respondents provided informed consent and anonymous interviews.

To prevent respondent duplication, biometrics (height, weight, and left/ right forearm length and wrist circumference) were collected during screening of potential respondents, and this information was entered into a password-protected RDS coupon manager to identify duplicates. Interviewers were also trained to detect impersonators through a short interview during the screening phase.

Questionnaires were administered to participants by trained nurses. They included questions regarding sociodemographic characteristics, sexual risk behaviors, drug use, and symptoms of STDs. These questions were loosely based on the RDS module used in a study of FSWs in Vietnam (Johnston et al. 2006) and on the FSW module of the Family Health International Behavioral Surveillance Surveys (Family Health International 2000). For RDS purposes, network size was measured using the question: “How many sex workers do you know in Shanghai? By knowing, I mean that you know their names and they know yours, and you have met or contacted them in the past month.” When recruiting participants returned to the interview site to collect their referral incentives, they were administered a follow-up questionnaire regarding their network alters. The number of members belonging to a participant’s three types of network alters were obtained using the following questions: (1) “Of the female sex workers you know, how many of those you invited accepted the invitation?” and (2) “Of the female sex workers you know, how many of those you invited rejected the invitation?” As a unique variation on standard RDS practice, a question was also asked about alters whom recruiting participants did not invite to participate: (3) “Of the female sex workers you know, how many did you not invite to participate?” We will refer to alters reported in response to the first two questions as invited alters and to alters reported in response to the third question as uninvited alters. Following each of these questions, recruiting participants were asked detailed information to characterize up to three of their invited alters who accepted the invitation, up to four of their invited alters who rejected the invitation, and their relationship with their invited and uninvited alters.

However, because of recruiting participants’ concerns with the length of the follow-up interview, especially if they had many social contacts, recruiting participants were asked to describe their uninvited alters as a group, rather than as individuals. Respondents were allowed to provide multiple responses to accommodate the uninvited group members’ diverse characteristics and relationship to their recruiter. For example, when asked to describe how close they were to their uninvited alters, respondents were asked “How close are you to these people [those whom you did not invite to participate]?” and they were allowed to select multiple options from among those provided (“very close,” “somewhat close,” and “not very close”).

Variables

Tier of sex work is a key variable in our analyses. Tier is used to establish whether FSWs differed with regard to sociodemographic characteristics and risk behaviors. Consistent with findings of previous research (Hershatter 1997; Huang et al. 2004; Parish and Pan 2006; Rogers et al. 2002; Xia and Yang 2005) and our own formative research, tier is a marker of social and economic position within the social organization of sex work.2 It also serves to assess the extent to which RDS was successful in reaching hidden and hard to reach segments of the FSW population in Shanghai. We identify three tiers to describe the organization of sex work: “high tier” includes women who solicit clients in karaoke bars, star hotels, discos, night clubs; “middle tier” includes women working in hair salons, massage parlors, foot cleaning and massage, sauna and bathhouses; and “low tier” includes women who solicit clients on the streets, parks, and other public spaces. For alters for whom we only had information from recruiting respondents’ reports (e.g., invited alters who refused to participate and uninvited alters), tier of sex work was assigned based on respondents’ answers to questions about the venues where their alters solicited clients.

As shown in Figure 1, recruited participants differed with respect to tier. Altogether, with the exclusion of the seven seeds, 188 participants were high tier, 305 were middle tier, and 22 were low tier. There was social crossover in recruitment mostly among adjacent tiers; only one of the recruitment links involved high- and low-tier sex workers. In the analyses below, because of the relatively small number of low tier sex workers recruited into the sample, the almost complete absence of recruitments between high and low tiers and recruitment patterns between and within middle and low tiers, we combine middle and low tiers into a single group.

Method

We produce point estimates of proportions of sex workers by tier and describe their characteristics using the V-H estimator (Volz and Heckathorn 2008) described earlier.

Confidence Intervals

To estimate confidence intervals of V-H estimates, we present in the online appendix (which can be found at http://smr.sagepub.com/supplemental/) a simple model-based bootstrap procedure. This procedure defines a resampling scheme to create a collection of samples which, consistent with the Markov model and Sampling Probability model used in the RDS literature (Salganik and Heckathorn 2004), has a distribution similar to the actual sampling process that generates the data. This is a variant of the bootstrap methodology presented in Salganik (2006) for the S-H estimator used in RDSAT. Volz and Heckathorn (2008) also described an algebraic variance estimation procedure designed specifically for use with the V-H estimator. However, their procedure (at least in its published form) was derived under the assumption that the recruitment chain was linear (i.e., there was no branching). Our procedure differs from Salganik’s (2006) and Volz and Heckathorn’s (2008) because (a) we use the observed branching structure of our sample in lieu of the linear structure and (b) we treat seeds as a fixed aspect of the sampling design, instead of sampling the entire data set when selecting seeds. Furthermore, the Volz and Heckathorn (2008) variance estimation formula has only been published in a form suitable for binary variables, while in our analyses we also deal with multicategory variables. Further details on our procedure are presented in the online appendix (which can be found at http://smr.sagepub.com/supplemental/). All of our estimates were independently derived using formulas described in Volz and Heckathorn (2008) and Salganik (2006) using the R statistical language (www.r-project.org). Preprocessing and all other descriptions of the data were performed using Stata 10.

Gauging Recruitment Biases and Their Effects on RDS Estimates

The bootstrap procedure used to produce the distribution of RDS estimates and described in the online appendix (which can be found at http://smr.sage-pub.com/supplemental/) can be extended to study the impact of different network structures on RDS estimates. A key feature of this bootstrap procedure is a matrix of estimated referral probabilities determined by the actual inter-and intra-group (i.e., tier) recruitments observed in the RDS sample. If we accept the RDS assumption of nonpreferential recruitment, this matrix will represent the maximum likelihood estimate of respondents’ recruitment choices under the Markov model. However, in the presence of preferential recruitment bias or rejection bias, actual or invited recruitments will not represent the egocentric network compositions of respondents. To gauge the amount of bias entailed by the respondents’ referral behavior and by invited alters’ patterns of refusal to participate and the impact of these biases on RDS estimates, we compare information on egocentric network composition from self-reports of recruiting participants and produce distributions of RDS estimates consistent with actual recruitment matrices, invited recruitment matrices, and all-alters recruitment matrices. Because our approach emphasizes the process that is assumed to generate the RDS sample, it can be used to study the impact of recruitment bias on any RDS estimator. Here, we use the procedure to quantify the impacts of rejection and preferential recruitment biases on the V-H estimator.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents V-H estimates (proportions and means) of selected sociodemographic characteristics and the 95 percent confidence interval bounds of proportions for 515 recruited participants classified by tier. In all, 24.8 percent of FSWs are in the high tier and 75.2 percent are in the middle/low tier. High-tier participants have a mean network size of 46.8, compared to middle-/low-tier FSWs who have a mean network size of 18.1. In the calculation of mean network size, we excluded seven extreme outliers (network size > 250) from among high-tier recruiters because their reports were not deemed reliable.3 The larger networks of high tier FSWs relative to those in the middle/low tier is not surprising. High tier FSWs work in establishments, such as karaoke halls, which typically employ a large number of workers, a number which can exceed 100. The social network size of high-tier sex workers is also sustained by high turnover of sex workers or by periodic rotation of FSWs across high-end establishments. This is a strategy adopted by establishment owners and pimps to guarantee clients a fresh supply of women. Conversely, the massage parlors and hair salons of middle tier sex workers can have as few as three FSWs and employ on average 10 to 15 FSWs.

Table 1.

Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics by Tier of Sex Work, V-H Adjusted Proportions and Means [percent CI] (CIs Generated with Modified Bootstrap Procedure in the Online Appendix).

| KTV/Karaoke/Hotel (High) | Hair/Massage/Sauna/Street (Middle/Low) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tier | 24.8 [20.7–29.3] | 75.2 [70.7–79.3] |

| Age | ||

| <25 | 49.3 [38.9–62.5] | 17.0 [11.6–25.7] |

| ≥25 | 50.7 [37.5–61.1] | 83.0 [74.3–88.4] |

| Education (%) | ||

| Primary or less | 18.9 [10.1–28.9] | 35.2 [26.1–44.2] |

| Junior high | 48.8 [39.0–59.6] | 50.9 [42.8–59.7] |

| Senior high | 32.3 [21.5–42.8] | 13.9 [9.0–19.1] |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Not married | 50.2 [40.3–61.8] | 20.2 [14.5–28.5] |

| Married/cohabiting | 26.6 [17.3–36.4] | 41.7 [34.1–50.1] |

| Divorced/Widowed | 23.2 [13.6–32.1] | 38.1 [28.6–45.1] |

| Monthly income | ||

| <6,710 RMB (mean) | 69.8 [57.5–79.0] | 82.5 [73.1–88.7] |

| ≥6,710 RMB (mean) | 30.2 [21.0–42.5] | 17.5 [11.3–26.9] |

| Unit price of sex (Chinese RMB) | ||

| <521 yuan (mean) | 40.7 [29.6–55.1] | 96.7 [93.6–98.8] |

| ≥521 yuan (mean) | 59.3 [44.9–70.4] | 3.3 [1.2–6.4] |

| Number of clients past month | ||

| ≤20 (mean) | 88.6 [81.2–93.8] | 65.7 [46.2–70.0] |

| >20 (mean) | 11.4 [6.2–18.8] | 34.3 [30.0–53.8] |

| Mean network size (unadjusted) | 46.8 | 18.1 |

| Total n | 188 | 327 |

Note: The sample size for all analyses in this table excludes the seven seeds.

Also from Table 1, there are marked differences in sociodemographic characteristics of Shanghai FSWs by tier of sex work. Compared to their lower tier counterparts, high-tier sex workers are younger, better educated, and are more likely to be single. Being married or divorced is a defining trait of middle-/low-tier sex workers. Differences in monthly earnings are also substantial as a greater proportion of high-tier sex workers earn greater than or equal to the mean monthly income for the sample (6,710 RMB). Despite a larger fraction of middle/low tier sex workers reporting at least 20 clients in the past month, a larger proportion of high tier sex workers (59.3 percent) earn at least the average price for one sexual encounter (521 yuan). High-tier sex workers can charge as much as 800 to 1,000 yuan for the entire night. Middle- and low-tier sex workers can serve as many as 5 to 6 clients in one day for compensations ranging between 50 and 300 yuan per service.4

To assess whether the hierarchical structure of Chinese FSWs is a source of bias in the RDS recruitment process, and in line with previous evaluations of recruitment bias (Iguchi et al 2009), we compare invited recruitment patterns by tier of sex work with patterns expected if participants recruited in a manner consistent with their all-alter network composition by tier. Because differences in participation of invited alters can also compound bias (invited alters can either accept or reject the coupon), we extend the comparison to the composition by tier of actual recruitments (i.e., invited alters who accepted the invitation to participate in the study).

A total of 273 recruiting participants reported on attributes of their invited and uninvited alters and of their relationship to them during the follow-up survey. However, because recruiting participants were asked to describe their uninvited alters as a group and were allowed to choose multiple response options, for each recruiting participant we assigned uninvited alters to individual attribute or relationship attribute categories according to the average distribution of the entire sample of invited alters. As an example of assignment to a category of an individual attribute, suppose 38 percent of all recruiting participants’ invited alters were reported to be in the middle/low tier by their recruiters while 62 percent were in the high tier. Based on this distribution, if a recruiting participant reported 20 uninvited alters and endorsed both tiers for the group, we assigned 8 individual uninvited alters to the middle/low tier (about 38 percent of 20) and 12 individual uninvited alters to the high tier (about 62 percent of 20). If, however, the recruiting participant only endorsed a single tier to describe the group of her uninvited alters, all uninvited alters were assigned to that tier. Similarly, as an example of assignment to a relationship attribute category, each recruiter was asked about her relationship with each invited alter with the question: “How would you describe your relationship to this person?” Choice options were friend; coworker; and coworker and friend. The average proportions of invited alters who were described as coworkers was 19 percent; friends 27 percent; and coworkers and friends 54 percent. If a recruiting participant reported 20 uninvited alters and endorsed the coworker, friend, and coworker and friend categories for the group, we assigned 4 individual alters to the coworker category (about 19 percent of 20), 5 individual alters to the friend category (about 27 percent of 20), and 11 alters to coworker and friend category (about 54 percent of 20). In the case of a recruiting participant endorsing only one response option, all individual uninvited alters were assigned the category endorsed. This assignment procedure produces a distribution of uninvited alters that approximates the distribution of invited alters, yielding a recruitment scenario friendly to nonpreferential recruitment and a suitable benchmark against which to evaluate violations of this assumption. Any deviation of observed recruitment patterns from recruitment patterns expected if participants recruited proportionately to their all-alter distribution would constitute evidence of recruitment bias. All assignments were completed using the R software package.

Table 2 compares actual, invited, and the all-alter network cross-recruitment patterns by tier. The tier distribution of the all-alter network was elicited from recruiting participants’ self-reports on invited and uninvited alters.

Table 2.

Actual and Observed Cross-tier Recruitment Ties and Distribution of All-alters Known by Recruiters by Tier for 174 Middle/Low Recruiters and 100 High-tier Recruiters.

| Recruiter’s Tier | Actual Recruitment

|

Invited Recruitment

|

All-alter Network

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n (percent)

|

n (percent)

|

n (percent)

|

||||

| High-Tier Alters | M/L tier Alters | High-tier Alters | M/L tier Alters | High-tier Alters | M/L tier Alters | |

| Middle/low (M/L) | 42 (13%) | 278 (87%) | 50 (12%) | 357 (88%) | 794 (27%) | 2,184 (73%) |

| High | 146 (75%) | 49 (25%) | 202 (81%) | 47 (19%) | 3,978 (81%) | 904 (19%) |

Note: M/L = Middle/low.

Actual recruitments are recruiters’ alters who were invited and accepted the invitation. These are recruiting participants’ effective recruitments. Invited recruitments are recruiters’ alters who were invited to participate, including those who accepted and rejected the invitation. All-alter network indicates all alters known by recruiters, including invited and uninvited alters. All percentages reflect row sums by actual recruitments, invited recruitments and all-alter network while cell n’s are the numerators.

In the top row, comparing actual, invited recruitments and all-alter network columns, middle-/low-tier sex workers reported knowing 27 percent high-tier sex workers but invited and effectively recruited 12 percent and 13 percent high-tier sex workers, respectively. Conversely, high-tier sex workers reported knowing 19 percent middle-/low-tier sex workers and also invited 19 percent, but the fraction of effectively recruited sex workers belonging to the middle/low tier was higher (25 percent). Put it differently, middle-/low-tier sex workers overinvited and effectively overrecruited from their own tier while high-tier sex workers invited alters from their own tier in a manner consistent with their self-reported all-alter network composition. However, high-tier sex workers were less effective than middle-/low-tier sex workers at recruiting their same-tier peers (compare 75 percent for the actual recruitment with 81 percent for the invited recruitment for high-tier recruiters and 87 percent and 88 percent for middle-/low-tier recruiters, respectively). If we use recruiters’ reports of the people they know by tier (the all-alter network) to represent “expected” recruitment patterns, then both high- and middle-/low-tier recruiters effectively recruited proportionately more middle-/low-tier sex workers than expected.

Before attributing discrepancies between actual, invited, and expected (all-alter) recruitment patterns to recruitment biases, we consider the extent to which these discrepancies are attributable to invalid self-reports on the number of alters by tier. Because of multiple recruitments, we could not exactly match recruiters’ reports about their alters who accepted their coupons during the follow-up interview with participants’ individual self-reports in the primary interview. Although we were unable to evaluate the validity of recruiters’ reports on their network composition by tier, we know recruiters reported consistently on their entire network size on two separate occasions. The number of sex workers respondents knew and reported in the main interview equaled the sum of the numbers of invited and uninvited alters they reported in the follow-up interview conducted one to three weeks later. Test–retest correlation between these consecutive reports of network size was .98. We also regard participants’ reports on their alters’ tier to be reasonably reliable. In the main interview, participants were asked to report their recruiters’ attributes. Thanks to the RDS coupon numbering system, it is possible to link participants to their recruiters and evaluate participants’ reports of their recruiters’ attributes against recruiters’ reports of their own attributes. For most attributes, including tier of sex work, consistency was very high with only a few participants misreporting the tier of sex work of her recruiters. Because participants’ reports on their recruiters appear to be reliable, we can place more confidence in recruiters’ reports on their network alters. This, compounded by evidence of internal validity of the network size measure, lends support to the statement that discrepancies observed in Table 2 are due to recruitment biases, not to invalid reports on the number of alters by tier.

Social barriers embedded in the hierarchical organization of sex work curtailed social interactions between tiers, especially upward recruitments by middle-/low-tier sex workers of high-tier sex workers. Middle-/low-tier sex workers favored extending invitations and effectively recruited within their same tier. On the other hand, despite high-tier sex workers showing no preference in choosing whom to invite (i.e., the invited network composition was consistent with their all-alter network composition by tier), they were less effective at recruiting their same-tier peers. Their experience of high rates of rejections from same tier alters may have been due to low social cohesion. In high-tier venues, the number of sex workers is large and workers’ turnover is high. These aspects of the organization of sex work may have prevented sex workers from forming trusted relationships with their peers. Trust is a critical element of disclosure because self-identification as a sex worker could result in negative social or legal consequences. If a trusted relationship is a necessary condition for extending or accepting an invitation from peers in the same tier, high-tier sex workers would have been reluctant to accept an invitation from colleagues they scarcely knew and did not trust.

To seek support for these explanations, we took advantage of questions asked of recruiting participants about the repertoire of their relationship with each invited alter and the group of alters they did not invite. After assigning relationship attribute categories for the group of uninvited alters using the procedure described earlier, we examined which relationship attributes between a recruiting participant and her alters were associated with extending an invitation.

We employed a logistic regression-fixed effects model using the xtlogit command in Stata 10.0 to assess whether any attribute of the relationship between a recruiter and her network alters was associated with the odds of inviting an alter. We applied a fixed-effects model to control for unobserved recruiter-level characteristics that may have influenced the recruitment process. Before running the final model, we assessed the severity of multicollinearity by analyzing the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each variable and found no VIF above 1.5.

The fixed-effect logistic regression model used to predict the odds of recruiter j passing the coupon to an alter i has the following form:

where Tij = type of relationship between recruiter j and alter i; Cij = closeness of relationship between recruiter j and alter i; Pij = place where recruiter j meets alter i; αj = unobserved individual effects of recruiter j; υij = error term.

Table 3 shows regression results by tier. In both tiers, a close relationship between a recruiter and her alters increased the odds of extending an invitation (among high tier: odds ratio [OR] = 4.91, 95 percent CI: [3.17–7.61]; among middle/low tier: OR = 4.78, 95 percent CI: [3.44–6.63]). The odds of extending an invitation were also greater if a recruiter and her alters met at a social place vs. a work place (among high tier: OR = 6.74, 95 percent CI: [4.22–10.76]; among middle/low tier: OR = 10.94, 95 percent CI: [7.65–15.63]). Among middle-/low-tier FSWs, the odds of offering a coupon to an alter were higher if a recruiter had a coworker and friend relationship with her alter, compared to just having a coworker relationship (OR = 1.82, 95 percent CI: [1.24–2.67]). A work relationship alone was less likely to generate trust especially in large venues where coworkers often do not know each other well.

Table 3.

Fixed-effects Logistic Regression Models: Odds of Passing a Coupon to an Alter by Relationship Attributes between Recruiter and Alters and Tier of Recruiter.

| Relationship Attributes | High-tier Recruiters (n = 100)

|

Middle-/Low-tier Recruiters (n = 174)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | SE | p | CI | OR | SE | p | CI | |

| Type of relationship | ||||||||

| Coworker (ref) | — | — | ||||||

| Friend | 0.64 | 0.17 | 0.10 | [0.38–1.08] | 1.06 | 0.24 | 0.80 | [0.68–1.66] |

| Coworker + friend | 1.40 | 0.30 | 0.11 | [0.93–2.12] | 1.82 | 0.36 | 0.00 | [1.24–2.67] |

| Closeness of relationship | ||||||||

| Not close (ref) | — | — | ||||||

| Close | 4.91 | 1.10 | 0.00 | [3.17–7.61] | 4.78 | 0.80 | 0.00 | [3.44–6.63] |

| Place where recruiter meets her alters | ||||||||

| Workplace (ref) | — | — | ||||||

| Social place (e.g., home, street) | 6.74 | 1.61 | 0.00 | [4.22–10.76] | 10.94 | 1.99 | 0.00 | [7.65–15.63] |

| LR χ2 (4) = 141.32; Prob > χ2 = 0.00 |

LR χ2 (4) = 295.50 Prob > χ2 = 0.00 |

|||||||

Note: OR = odds ratio.

Table 4 shows the distribution of reasons provided by recruiting participants as to why they offered a coupon to their invited alters. “Having a trusted relationship” with these alters was the dominant response. Similarly, recruiters’ most frequently cited reason for withholding invitations from alters was that they did not feel very close to them. RDS participation requires a recruiter to invite alters who are sex workers and a participant to acknowledge her sex worker identity to her recruiter. Among the reasons provided by recruiters as to why alters rejected the invitation to participate in the study, fear of being identified as sex workers stood out among reports by recruiters in both tiers. Taken together, these results lend support to the explanation advanced earlier that low social cohesion in their work environment may have been the reason that high-tier sex workers were ineffective at recruiting from their own tier.

Table 4.

Distribution of Reasons Provided by Recruiting Participants for Why They Offered Coupons to Their Alters, Why They Withheld Coupons, and Why They Thought Their Alters Rejected the Invitations.

| Reason Why She Invited This Alter | High-tier Percent

|

Middle-/Low-tier Percent

|

|---|---|---|

| n = 191 | n = 324 | |

| I trust her | 76 | 72 |

| We work together | 51 | 29 |

| I wish her to participate in the study | 41 | 40 |

| I often see her | 40 | 46 |

| She needs the money that comes with the incentive | 24 | 42 |

| I wish her to be tested for STDs | 23 | 11 |

| She is the first person I met | 19 | 17 |

|

| ||

| Reason for why she withheld coupons from these uninvited alters | n = 99 | n = 169 |

|

| ||

| We are not very close | 48 | 62 |

| I have not known them for long | 39 | 15 |

| We don’t get along | 22 | 11 |

| They don’t need the money that comes with the incentive | 21 | 15 |

| I don’t see them often | 16 | 28 |

| They don’t know I know they are sex workers | 6 | 8 |

|

| ||

| Reason why this alter refused her invitation | n = 83 | n = 104 |

|

| ||

| She was afraid of being identified as a sex worker | 80 | 85 |

| She felt uncomfortable about this study | 28 | 10 |

| She was too busy | 8 | 6 |

| She had no clients within the past month (not eligible) | 4 | 2 |

| The size of the incentive was not worth her time | 2 | 0 |

| The interview location is too far away | 2 | 4 |

| She was not interested | 1 | 7 |

Gauging the Effect of Respondents’ Recruitment Behaviors on RDS Estimates

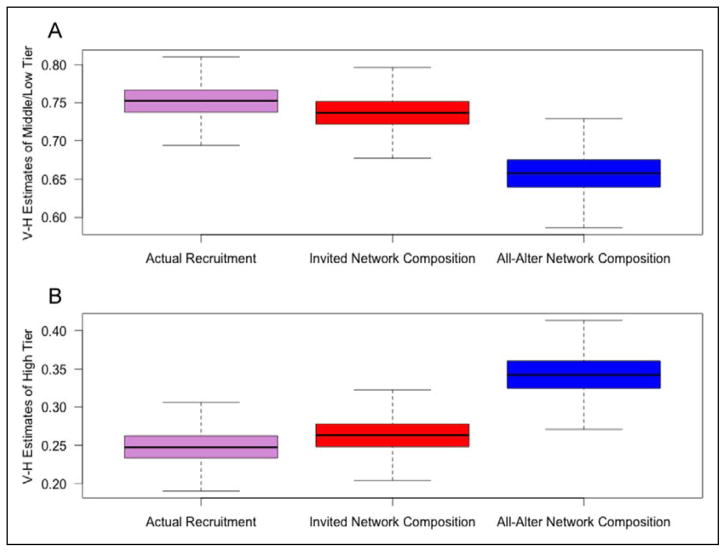

Figure 2A and B present the distribution of V-H estimates obtained with the bootstrap procedure described in the online appendix (which can be found at http://smr.sagepub.com/supplemental/) and applied to study the impact of alternative egocentric network compositions on the RDS estimates. In line with the terms used in Table 2, the alternative network compositions are drawn from the “actual” RDS recruitment matrix of invited recruitments who accepted to participate, the invited recruitment matrix of alters who were offered a coupon (including those who accepted and rejected the coupon) and the all-alter network composition based on recruiting participants’ self-reports on the tier of all their network alters, including alters who were not invited to participate.

Figure 2.

A. Distribution of V-H estimates of proportion of middle-/low-tier sex workers resulting from the bootstrap procedure under various recruitment regimes. B. Distribution of V-H estimates of proportions of high tier sex workers resulting from the bootstrap procedure under various recruitment regimes.

The difference between the distribution of RDS estimates from the bootstrap procedure consistent with “actual recruitments” and the distribution of estimates consistent with the “all-alter network composition” represents the effect of preferential recruitment compounded by rejection bias on the RDS estimates. The difference between the distributions produced by “invited recruitments” and expected recruitments based on the all-alter network composition represents the effect of preferential recruitment alone. The medians of the distribution of estimates of middle-/low-tier sex workers and high-tier sex workers from the actual recruitment matrices are respectively higher and lower than the medians of estimates produced under scenarios of expected recruitments. Neither of the two distribution medians lies within the other’s confidence interval, which suggests that the difference is statistically significant. These findings suggest that overrecruitment of middle-/low-tier participants by members of their own tier and effective underrecruitment of high-tier participants by members of their own tier lead to an overestimate of the proportion in middle-/low-tier sex workers and an underestimate of the proportion of high-tier sex workers. The direction of the bias is consistent with the results of another empirical study (Iguchi et al. 2009) and with a simulation study which showed that biased referral in favor of a particular group resulted in increased positive bias in the V-H estimate of that group (Gile and Handcock 2010). This is not surprising since overrecruitment by middle-/low-tier sex workers of same-tier peers and underrecruitment of same-tier peers by high-tier sex workers leads to more middle-/low-tier nodes and fewer high-tier nodes recruited into the sample, but this type of recruitment bias is assumed away by the V-H estimator.

Discussion and Conclusion

RDS is an increasingly popular method for sampling populations who are too small to show up in standard probability sampling designs and/or defined with reference to invidious status characteristics not likely to be revealed by omnibus survey research. Its aim is to provide a probability-based inferential structure for representations of these hidden or hard-to-reach populations that capitalizes on their network structure to identify and interview subjects. RDS is potentially quite valuable, but its validity relies on an idealized model of how sample subjects make referrals to new subjects and how potential respondents are recruited into the sample. With this article, we move considerations regarding the RDS sampling process from the theoretical to the empirical realms. We used recruitment data collected with a special network module added to the standard RDS protocol in a population of FSWs in Shanghai. We established empirical estimates of bias in the process that the RDS participants used in selecting contacts for referral and assessed the effect of recruitment behavior on RDS estimates of population characteristics.

Similar to other FSW populations across Asia among whom RDS is routinely conducted, the organization of sex work in China is sustained by a hierarchical class structure, from high to low tier, which governs and constrains interpersonal and inter-tier relationships and promotes different levels of social cohesion. These features can interfere with the RDS referral process which assumes that participants will select other participants from among their personal networks at random. Our description of recruitment patterns by tier suggested that middle-/low-tier sex workers favored extending invitations to network alters from their own tier more so than one would expect if they recruited consistently with the tier composition of their whole network. This is possibly due to their limited interactions with high-tier sex workers because of differences in age, education, and relative social status within the sex work hierarchy. On the other hand, high-tier sex workers extended invitations consistently with their reported network composition but effectively underrecruited from their own tier. This was somewhat surprising because the typically large work places of high-tier sex workers and their relatively larger networks provide abundant pools of potential recruits whom to select from. However, high-tier sex workers’ low social cohesion and fear of legal and social consequences associated with disclosure of their identity to people they do not know and trust may have prevented them from effectively recruiting their peers. These recruitment biases by members of the two tiers resulted in a positive bias in the estimated proportion of middle-/low-tier sex workers and a negative bias in the estimated proportion of high-tier sex workers.

Biased recruitment in the chain referral process is highly relevant to the ability of RDS to provide an inferential structure for representation of hidden populations whose health dynamics are in need of accurate descriptions. Although comparisons such as the ones presented here are only easier to undertake for observable characteristics, and are not readily extended to HIV status or HIV-risk behaviors, it is likely that the bias we gauge based on observable characteristics also applies to health status and health-related behaviors. In the context of FSWs in Shanghai, the RDS referral process steered recruitment away from high-tier sex workers who are less vulnerable than middle-/low-tier sex workers to risky behaviors such as unprotected sex or high client turnover. High-tier sex workers have greater means to refuse to provide sexual services and are in a better position to negotiate the use of condoms (Dandona et al. 2005; Huang et al. 2004; Muñoz et al. 2010; Pirkle et al. 2007; Wong et al. 2003). Patterns of preferential recruitment observed in this RDS study of sex workers in Shanghai biased the sample and proportion estimates away from low-risk segments in favor of high-risk segments of the population.

Our analyses may suffer from potential limitations. One stems from the fact that our descriptions of participants’ recruitment behaviors on the ground are based on attributes of alters elicited from recruiting participants’ self-reports. The indirect evidence we have provided on the validity and reliability of these reports alleviates but does not completely remove the uncertainty that errors in self-reported network composition rather than recruitment biases may explain the discrepancy between actual and expected recruitments.

Second, our procedure to disaggregate group-level information on uninvited alters and assign attributes to uninvited alters based on the average distribution of invited alters may be coarse. However, this approach is friendly to the RDS assumption of proportional, nonpreferential recruitment and provided a framework to identify systematic deviations from nonpreferential recruitment. These deviations resulted in measurable impacts on the RDS estimates. Incorporating deviations at the individual level may have resulted in even greater impacts on the RDS estimates and the variance of those estimates.

Third, eliciting group-level information from recruiters on uninvited alters is naturally inferior to obtaining individual-level information, but it is practical. In the particular instance of FSWs in Shanghai, insisting on obtaining information on each uninvited alter would have resulted in respondent fatigue and limited our ability to collect any information on uninvited alters. Moving forward, an easier and potentially feasible approach to collecting data on attributes of uninvited alters could be to elicit information from recruiters on the size of subgroups of uninvited alters by attributes of interest. This approach would directly yield the composition of uninvited alters by the attribute of interest while minimizing the burden on respondents. Introducing items to elicit counts of network alters by key attributes in the main questionnaire would also provide data for assessing the internal consistency of measures of network size and composition. In addition to helping identify sources of recruitment bias and assess the validity of network items, data on the all-alter network composition will enable the adjustment of estimates for bias via poststratification. Promising work on poststratification and network sampling is being undertaken by Schutt, Gelman, and McCormick (2011).

Our data collection, analyses, and conclusions apply to FSW populations in Asia. Asian sex worker populations are commonly stratified by tier, and our study provides a useful example of how RDS fares as a sampling and estimation method in these populations. We expect that ongoing and future studies will empirically track the recruitment process and develop new tools for the diagnosis of violations of RDS assumptions in other hidden populations, so as to enrich our knowledge of how RDS assumptions fare across a wide range of real-world networks and populations.

In this article, we have evaluated a single RDS assumption while forgoing to address other crucial ones. There are several reasons for an exclusive focus on the nonpreferential recruitment assumption. First, the ego-centric network module was designed to implement an assessment of random recruitment. Second, this assumption provides support for the assumption that the probability of an individual being included in the sample is exactly proportional to the number of reciprocal ties she has with other members of the target population (the SPPD assumption). Indeed, our examination of recruitment behaviors of FSWs has shown that, in addition to degree, other factors may influence whether or not members of this population are included in the sample. The assumption of nonpreferential recruitment constrains researchers from directing or guiding the referral process toward members of the population who are likely to be missed. The inability to redirect (or adapt) the chain referral process is a significant restriction and, as we have shown for the case of FSWs in China, can prove particularly problematic for a potential respondents to be recruited into the sample and for RDS to produce unbiased estimates of population proportions. Future research should address efforts to use information on actual recruitment to adapt the referral process in an improved RDS methodology that is free from assumptions about the unobserved structure of the social network and incorporates statistical model-based estimates of sample inclusion probabilities which account for the observed recruitment process.

One example of how information on the observed referral process can be incorporated into an improved RDS methodology is provided by the variant of Salganik’s bootstrap methodology (2006) we present in the online appendix (which can be found at http://smr.sagepub.com/supplemental/) to estimate CIs of V-H estimates and measure the impact of violation of the nonpreferential recruitment assumption on the estimates. Our bootstrap estimator uses the observed branching structure of the sample, rather than assuming a linear branching structure as in Volz and Heckathorn (2008) and Salganik (2006). Also, unlike Salganik (2006), we treat seed selection as a fixed feature of the sampling design because in RDS seeds are typically selected by the researcher using criteria of convenience. Steps in the direction described above, some of which are currently being undertaken (Gile 2011; Gile and Handcock 2011), will enable improvements to the RDS methodology: (1) using a statistical model to estimate inclusion probabilities that will account for the impact of using approximate inclusion probabilities on the validity of the estimates; (2) adapting the referral process and relaxing the random recruitment assumption, provided that this adaptation is included in the model; and (3) incorporating factors other than degree in model estimates of inclusion probabilities.

RDS is becoming increasing popular as a sampling strategy for hidden populations because, in many settings, it has proven to be the most efficient, practical, and low-cost method for recruiting samples of hidden populations. Continuing empirical evaluations of violations of RDS assumptions in real-world settings and improvements in the methodology for population representation should be important developments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The empirical grounding of this article is based on the Shanghai Women’s Health Survey, 2007. The data collection was funded by a Ford Foundation grant to the Shanghai Institute of Planned Parenthood Research (Ersheng Gao, PI) and an administrative supplement to NICHD grant R21HD047521 (Merli, PI). Data analyses were funded in part by NICHD grant R01 HD068523-01 (Merli, PI) and a Duke Global Health Institute postdoctoral fellowship to Thespina Yamanis.

Biographies

Thespina J. Yamanis is an assistant professor at American University’s School of International Service. Her research focuses on understanding and targeting the social determinants of HIV risk behavior and reaching and intervening with high risk and vulnerable populations. Her published work has focused on the social and sexual networks of adolescent men at risk of HIV in Tanzania and their patterns of violence toward women. She is currently leading two studies that examine the social and structural influences on young men for engaging in high-risk sexual partnerships in Tanzania and the District of Columbia.

M. Giovanna Merli is an associate professor of Public Policy, Sociology, and Global Health at Duke University and an associate director of the Duke Population Research Institute. Her research focuses on the influence of social dynamics and social policy on population change and HIV transmission in China and other less developed countries. Her recent publications focus on the modeling of the spread of HIV/AIDS in low HIV prevalence countries with particular attention to micro- and macro-level factors associated with HIV infection and transmission, and an emphasis on the role of social and sexual networks in the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases in China. She is the PI of a recent R01 grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to evaluate the Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) methodology and improve RDS estimation among female sex workers in China.

William Whipple Neely is an independent statistical consultant in Seattle, Washington. He holds two doctoral degrees, one in statistics and one in mathematics. His research focuses on developing rigorous statistical methodologies for data collected using respondent-driven sampling (RDS) and developing a framework for quantifying the uncertainty in RDS estimates due to the approximation of sample inclusion probabilities. His work received financial support from the National Science Foundation and an article from his RDS work is currently under review. He is currently collaborating with Dr. Merli to improve the RDS methodology for estimating disease prevalence among female sex workers in China.

Felicia Feng Tian is a PhD candidate in Sociology at Duke University. She conducts research on marriage formation and transitions to adulthood in China.

James Moody is the Robert O. Keohane Professor of Sociology at Duke University. His research focuses on the structural dynamics of social networks, using computational tools to model patterns of relations among actors. The substantive contexts of his work range widely, touching on areas as diverse as the dynamics of high school friendship networks, the spread of HIV/AIDs, collaboration among scientists and network visualization. He is currently completing a book on Visualizing Social Interaction (Princeton U Press), which is a visual history of the social network analysis field. He is currently collaborating with Dr. Merli to improve the RDS methodology for estimating disease prevalence among female sex workers in China.

Xiaowen Tu is a senior researcher at the Department of Epidemiology and Social Sciences, Shanghai Institute of Planned Parenthood Research, Shanghai, China. Her research focuses on health problems related to sexual and reproductive health of adolescents, HIV risk behaviors and STDs among female sex workers, and gender-based violence. Her publications have focused on adolescent reproductive health and HIV risk behaviors among female sex workers in China.

Ersheng Gao is a professor at the Department of Epidemiology and Social Sciences, Shanghai Institute of Planned Parenthood Research, Shanghai, China. He is also the director of the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Center for Research in Human Reproduction.

Footnotes

It should be noted that, in contrast to the ease with which RDS recruited FSWs in Asia, RDS performed poorly in recruiting female sex workers (FSWs) in two cities in Estonia and Russia (Simic et al. 2006). The authors concluded that this may have been due to the inability of FSWs in these contexts to independently form networks.

Formative research in Shanghai included (a) in-depth interviews with a small sample (n = 15) of sex workers stratified by the type of establishment where they solicited their clients; and (b) conversations with scholars and health officials familiar with the social organization of sex work in Shanghai.

Large network sizes are not influential because, with the RDS weighting scheme, they contribute very little to the estimates.

To put these earnings in perspective, middle-/low-tier monthly earnings are higher than the average earnings of female migrants in Shanghai—an appropriate comparison group since all but three of the respondents in the RDS survey originated from outside Shanghai—who, in interviews for a parallel survey of sexual behavior of the Shanghai general population, reported mean monthly earnings of 1,130 yuan for female migrants with similar levels of education (Merli and Morgan 2012).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- Blankenship Kim, West Brooke, Kershaw Trace, Biradavolu Monica. Power, Community Mobilization, and Condom Use Practices among Female Sex Workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS. 2008;22:S109–16. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000343769.92949.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Zhi-Qiang, Zhang Guo-Cheng, Gong Xiang-Dong, Lin Charles, Gao Xing, Liang Guo-Jun, Yue Xiao-Li, Chen Xiang-Sheng, Cohen Myron S. Syphilis in China: Results of a National Surveillance Programme. The Lancet. 2007;369:132–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandona Rakhi, Dandona Lalit, Gutierrez Juan P, Kumar Anil G, McPherson Sam, Samuels Fiona, Bertozzi Stefano M the ASCI FPP Study Team. High Risk of HIV in Non-brothel Based Female Sex Workers in India. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Yanpeng, Detels Roger, Zhao Zaiwei, Zhu Yong, Zhu Guanghui, Zhang Bowei, Shen Tao, Xue Xueshan. HIV Infection and Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Female Commercial Sex Workers in China. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;38:314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Health International. Guidelines for Repeated Behavioral Surveys in Populations at Risk of HIV. 2000 Retrieved August 30, 2010 ( http://www.fhi.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/en/HIVAIDS/pub/guide/bssguidelines.htm)

- Gil Vincent E, Wang Marco S, Anderson Allen F, Lin Guo M, Wu Zongjian O. Prostitutes, Prostitution and STD/HIV Transmission in Mainland China. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;42:141–52. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gile Krista J. Improved Inference for Respondent-driven Sampling Data with Application to HIV Prevalence Estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2011;106:135–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gile Krista J, Handcock Mark S. Respondent-driven Sampling: An Assessment of Current Methodology. Sociological Methodology. 2010;40:285–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9531.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gile Krista J, Handcock Mark S. Network model-Assisted Inference from Respondent-Driven Sampling Data. 2011 doi: 10.1111/rssa.12091. arXiv:1108–0298. Under Revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel Sharad, Salganik Matthew J. Respondent-driven Sampling as Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:2202–29. doi: 10.1002/sim.3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel Sharad, Salganik Matthew J. Assessing Respondent-driven Sampling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:6743–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000261107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Qun, Wang Ye, Li Yan, Zhang Yurun, Lin Peng, Yang Fang, Fu Xiaobing, Li Jie, Raymond H Fisher, Ling Li, McFarland Willi. Accessing Men Who Have Sex with Men through Long-Chain Referral Recruitment, Guangzhou, China. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;22:93–96. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9388-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations. Social Problems. 1997;44:174–99. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD, Jeffri Joan. Assessing the Feasibility of Respondent-driven Sampling: Aging Artists in New York City. Blogs. 2005 Retrieved July 19, 2011 ( http://www.tc.columbia.edu.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/rcac/acrobat/IOA3_aging_feasibility.pdf)

- Heckathorn Douglas D, Semaan Salaam, Broadhead Robert S, Hughes James J. Extensions of Respondent-driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Injection Drug Users Aged 18–25. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hershatter G. Dangerous Pleasures. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Yingying, Henderson Gail E, Pan Suiming, Cohen Myron S. HIV/AIDS Risk among Brothel-based Female Sex Workers in China: Assessing the Terms, Content, and Knowledge of Sex Work. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:695–700. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000143107.06988.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi Martin Y, Ober Allison J, Berry Sandra H, Fain Terry, Heckathorn Douglas D, Gorbach Pamina M, Heimer Robert, Kozlov Andrei, Ouellet Lawrence J, Shoptaw Steven, Zule William A. Simultaneous Recruitment of Drug Users and Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States and Russia Using Respondent-driven Sampling: Sampling Methods and Implications. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86:5–31. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9365-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston Lisa G, Sabin Keith, Hien Mai T, Huong Pham T. Assessment of Respondent-driven Sampling for Recruiting Female Sex Workers in Two Vietnamese Cities: Reaching the Unseen Sex Worker. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:16–28. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9099-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston Lisa G, Khanam Rasheda, Reza Masud, Khan Sharful I, Banu Sarah, Alam Md S, Rahman Mahmudur, Azim Tasnim. The Effectiveness of Respondent-driven Sampling for Recruiting Males Who have Sex with Males in Dhaka, Bangladesh. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:294–304. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall Carl C, Kerr Ligia R, Gondim Rogerio C, Werneck Guilherme L, Macena Raimunda H, Pontes Marta K, Johnston Lisa G, Sabin Keith, McFarland Willi. An Empirical Comparison of Respondent-driven Sampling, Time Location Sampling, and Snowball Sampling for Behavioral Surveillance in Men Who Have Sex with Men, Fortaleza, Brazil. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:97–104. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau Joseph T, Tsui Hi Yi, Siah PC, Zhang KL. A Study on Female Sex Workers in Southern China (Shenzhen): HIV-related Knowledge, Condom Use and STD History. AIDS Care. 2002;14:219–33. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Lin L. The Sex Sector: The Economic and Social Bases of Prostitution in Southeast Asia. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Lu, Jia Manhong, Ma Yanling, Yang Li, Chen Zhiwei, Ho David D, Jiang Yan, Zhang Linqi. The Changing Face of HIV in China. Nature (London) 2008;455:609–11. doi: 10.1038/455609a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Fan, Jia Yujiang, Sun Xinhua, Wang Lan, Liu Wei, Xiao Yan, Zeng Gang, Li Chunmei, Liu Jianbo, Cassell Holly, Chen Huey T, Vermund Sten H. Prevalence of HIV Infection and Predictors for Syphilis Infection among Female Sex Workers in Southern China. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2009;40:263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Xin, Bengtsson Linus, Britton Tom, Camitz Martin, Kim Beom Jun, Thorson Anna, Liljeros Fredrik. The Sensitivity of Respondent–Driven Sampling. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2011;175:191–216. [Google Scholar]