This study reports the successful reprogramming of human fibroblasts into a state of pluripotency by baculoviral transduction-mediated, site-specific integration of OKSM transcription factor genes into the AAVS1 locus in human chromosome 19. Methods based on site-specific integration of reprogramming factor genes as reported here hold the potential for efficient generation of genetically amenable induced pluripotent stem cells suitable for future gene therapy applications.

Keywords: Induced pluripotent stem cells, Gene delivery systems in vivo or in vitro, Gene expression, Cre-loxP system

Abstract

Integrative gene transfer using retroviruses to express reprogramming factors displays high efficiency in generating induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), but the value of the method is limited because of the concern over mutagenesis associated with random insertion of transgenes. Site-specific integration into a preselected locus by engineered zinc-finger nuclease (ZFN) technology provides a potential way to overcome the problem. Here, we report the successful reprogramming of human fibroblasts into a state of pluripotency by baculoviral transduction-mediated, site-specific integration of OKSM (Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-myc) transcription factor genes into the AAVS1 locus in human chromosome 19. Two nonintegrative baculoviral vectors were used for cotransduction, one expressing ZFNs and another as a donor vector encoding the four transcription factors. iPSC colonies were obtained at a high efficiency of 12% (the mean value of eight individual experiments). All characterized iPSC clones carried the transgenic cassette only at the ZFN-specified AAVS1 locus. We further demonstrated that when the donor cassette was flanked by heterospecific loxP sequences, the reprogramming genes in iPSCs could be replaced by another transgene using a baculoviral vector-based Cre recombinase-mediated cassette exchange system, thereby producing iPSCs free of exogenous reprogramming factors. Although the use of nonintegrating methods to generate iPSCs is rapidly becoming a standard approach, methods based on site-specific integration of reprogramming factor genes as reported here hold the potential for efficient generation of genetically amenable iPSCs suitable for future gene therapy applications.

Introduction

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), generated through reprogramming differentiated somatic cells by transduction with a defined set of transcription factor genes, are attractive cell sources not only for in vitro developmental biology study and drug screening but also for medical applications as cellular therapeutics [1, 2]. Both genome integration and nonintegration methods can be used to generate iPSCs. Integrative reprogramming approaches using random integrating retroviral or lentiviral systems are efficient but pose the risk of insertional mutagenesis, oncogene activation, and cellular transformation [3, 4]. Furthermore, expression of a randomly integrated transgene in mammalian cells is unpredictable, and integration within certain DNA sequence contexts can trigger epigenetic silencing and cease transgene expression over time [5, 6]. Nonintegrative reprogramming by means of transfection and transduction of protein, mRNA, microRNA, plasmid, and episomal viral vector is safer but often suffers from low efficiency and/or being difficult to perform. Obviously, there remains a need for new reprogramming methods that are relatively safe yet efficient, despite methodological improvements in iPSC generation over the past few years.

Zinc finger nuclease (ZFN)-mediated targeted gene disruption or gene addition is a powerful tool for functional gene analysis and holds great potential in medical applications [7], including stem cell research and applications [8, 9]. In this approach, an artificial endonuclease is constructed by fusing a zinc-finger DNA-binding domain that recognizes a specific DNA sequence with the nuclease domain of the FokI endonuclease, and a pair of ZFNs is used to specifically bind the sequence of interest in the opposite orientation. When ZFNs bind the target sites, FokI dimerizes and cleaves the DNA in its immediate vicinity, creating a double-strand break (DSB). ZFN-induced DSBs can be repaired by error-prone nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), which often leads to small insertion or deletion. The induction of DSBs can also stimulate the homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DNA repair machinery, a process that faithfully copies the genetic information from a donor DNA molecule of related sequence, leading to HR-mediated integration of the donor DNA into the break site with high efficiency and accuracy [7].

A recent study using plasmid transfection of human primary cells has demonstrated the generation of iPSCs by ZFN-mediated targeted insertion of reprogramming factor genes into the chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 (CCR5) locus, but a relatively low reprogramming efficiency of 0.04% was reported [10]. It appears that low efficiency of cotransfection of ZFNs and a large donor DNA carrying reprogramming factor genes in primary cells represents a major hurdle for the exploitation of ZFN technology for reprogramming of human primary cells.

In the current study, we examined the hypothesis that transduction of human somatic cells with more powerful viral vectors can be used to improve the insertion efficiency of reprogramming factor genes at a ZFN-specified locus, thus increasing reprogramming efficiency. We tested recombinant DNA vectors derived from the insect baculovirus Autographa californica multiple nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV), a type of delivery vector capable of transducing a wide variety of human cell types [11, 12], and developed a baculovirus (BV)-ZFN system for AAVS1 locus-directed homologous recombination. The AAVS1 locus, a common integration site of adenoassociated virus 2, lies within the first intron of the gene encoding the protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 12C (PPP1R12C) on human chromosome 19 (19q13.3-qter) and is considered as a nonpathogenic “safe harbor” for the addition of a transgene into human genome [5, 13]. We report here that BV transduction-mediated ZFN expression is a simple and efficient method for integrative gene transfer of reprogramming factors to generate human iPSCs.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid and Recombinant BV Vectors

pFastBac1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.invitrogen.com), a donor plasmid that allows the gene of interest to be transferred into a baculovirus shuttle vector (bacmid) via transposition, was used as a plasmid backbone to construct recombination plasmids for baculovirus generation. To construct pFB-ZFN, a pFastBac1 vector expressing ZFNs, two DNA fragments encoding the right and left ZFNs, 993 base pairs (bp) each, were synthesized using GeneArt Gene Synthesis service (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.lifetech.com) based on the amino acid sequences previously reported [14]. The engineered ZFNs contain the right and left homologous arms pertaining to the AAVS1 locus fused with an obligate heterodimer form of the FokI endonuclease [15]. The synthesized constructs were cloned into pMA (ampR) (Life Technologies). The two fragments were then amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and subcloned into pFastBac1 using NotI/XbaI for the right ZFN and KpnI/HindIII the left ZFN, respectively. The 1.1-kb human elongation factor 1α (EF1α) promoter was then amplified from pFB-EF1α-EGFP-hyg-lox [16] and cloned into the above construct using BamHI/NotI to drive the expression of ZFNs. Finally, a 0.6-kb internal ribosome entry site (IRES) was amplified from pIRES (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, http://www.clontech.com) and inserted between the right and left ZFN open reading frames using XbaI/KpnI. AAVS1 begins 424 bp upstream of the 5′-end of exon 1 of the PPP1R12C gene and ends 3.35 kb downstream of the 3′-end. The region that we used pFB-ZFN to target is within intron 1 of the PPP1R12C gene.

To construct the donor plasmid pFB-OKSM (Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-myc) with reprogramming factors, an 810-bp left homologous arm and an 837-bp right homologous arm pertaining to the AAVS1 locus were amplified from pZDonor-AAVS1 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com) and inserted using SnaBI/SalI for the left homology arm and NotI/BstBI for the right homology arm into pFB-PGK-Neo-EGFP-LoxP, a pFastBac1 vector containing heterospecific loxP sites constructed in the laboratory previously [16]. Then, a polycistronic cassette from pHAGE-EF1α-STEMCCA (Millipore, Bedford, MA, http://www.millipore.com) was inserted using EcoRI/AscI. The cassette contains the EF1α promoter; human Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-myc genes joined with self-cleaving 2A sequence and IRES as a fusion gene (OSKM); and the woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE). To construct pFB-mCherry, we replaced the OSKM polycistronic cassette with the mCherry gene and the neomycin resistance gene with the hygromycin-B-resistance gene in pFB-OKSM. The construction of pFB-Cre was reported previously [16]. Primers used for vector construction are listed in supplemental online Table 1.

Recombinant BVs, including BV-ZFN, BV-OKSM, BV-mCherry, and BV-Cre, were generated using pFB-ZFN, pFB-OKSM, pFB-mCherry, and pFB-Cre, respectively, and propagated in Sf9 insect cells according to the protocol of the Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System from Invitrogen. Recombinant DNA research in this study followed the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

The T7E1 Assay

We used a mismatch-sensitive endonuclease assay to determine whether BV-ZFN could induce DNA cleavage at the target site. HEK293T cells were transduced with BV-ZFN at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 200 or 400 plaque forming units (pfu) per cell overnight, and genomic DNA was extracted from treated HEK293T cells with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, http://www.qiagen.com) 3 days later. A 476-bp fragment containing the ZFN cutting site within the AAVS1 locus was amplified with forward primer GGATTCGGGTCACCTCTCAC and reverse primer TCTCTGGCTCCATCGTAAGC using the HiFi PCR kit (Invitrogen). The PCR products were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen), denatured, reannealed, and then digested with the mismatch-sensitive T7E1 endonuclease (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA). The fragments were separated with 2.5% agarose gel.

γ-H2AX Expression Analysis and Cell Viability Assay

To assess nuclease-associated genome toxicity, we monitored phosphorylation events of histone H2AX (γ-H2AX), which correlate to DNA DSBs [17, 18]. Cells were transduced with BV-ZFN at an indicated MOI for overnight and harvested 3 days later for staining using anti-γH2AX (Abcam, Cambridge, U.K., http://www.abcam.com) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate antibodies. Cell viability was determined by CellTiter 96 AQueous Assay using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (Promega, Madison, WI, http://www.promega.com). The relative cell growth (%) compared with control cells was calculated as follows: (Absorbance of sample − Absorbance of blank)/(Absorbance of control − Absorbance of blank) × 100%.

Generation of Human iPSCs

Human iPSCs were generated from human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) (Millipore) by cotransduction of BV-ZFN and BV-OKSM. Specifically, 1 × 104 HFFs at passages 3–5 were seeded into one well of a six-well plate in FibroGRO LS complete medium (Millipore) 1 day before baculoviral transduction. The cells were transduced with the two BV vectors at an MOI 50 or 100 pfu per cell each for 4–6 hours. Two days later, 200 μg/ml Geneticin (G418) (Life Technologies) was added to select the cells for 7 days. On day 10, the cells were transduced again under the same conditions described above. On day 15, the transduced HFF cells were dissociated and replated onto one well in a fresh six-well plate seeded with mitomycin C-inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in a human iPSC medium consisting of 80% Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12), 20% KnockOut Serum Replacer (Invitrogen), 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, http://www.peprotech.com), and penicillin/streptomycin. The medium was replaced daily. iPSC colonies that were compact and had embryonic stem cell (ESC)-like morphology with defined borders were mechanically isolated between day 20 and day 30 and expanded on MEFs in the human iPSC medium. Possible iPSC colonies were assessed using alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining with the AP substrate kit (Millipore).

iPSC Differentiation and Characterization

The details on bisulfite sequencing of iPSC genomic DNA; differentiation of human iPSCs into embryoid bodies (EBs) and neural stem cells (iPS-NSCs); differentiation of iPS-NSCs into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes; teratoma formation assay; and immunofluorescence staining of iPSCs and their derivates are provided in the supplemental online data. For reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of iPSCs and derived cells, total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Primers used are listed in supplemental online Table 1. PCR amplified products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel.

For PCR genotyping and Southern blot analysis of iPSCs, genomic DNA of cells was isolated using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen). PCR genotyping was used to detect ZFN-mediated homologous recombination and Cre recombinase-mediated cassette exchange events. PCR amplification of genomic DNA was performed using KAPA HiFi Hotstart Readymix (KAPA Biosystems, Woburn, MA, http://www.kapabiosystems.com). Amplified products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. Genomic DNA used for Southern blot analysis was digested overnight with NcoI or EcoRI. The digested DNA was loaded on a 1% agarose gel, and electrophoresis was performed for 16 hours at 25 V. Using the iBlot Dry Blotting System (Invitrogen), the DNA was then transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane. The membrane was washed and air-dried. After UV cross-linking at 130 mJ/cm2, the membrane was hybridized with DIG-labeled probes overnight in the hybridization buffer DIG Easy Hyb (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, http://www.roche.com). DIG-labeled probes targeting the WPRE region of the donor cassette were synthesized using the PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche). Following hybridization the membrane was washed, blocked, and then incubated with an anti-DIG antibody (DIG DNA Labeling and Detection Kit; Roche) that was detected by CDP-Star, ready-to-use (Roche).

DNA sequencing was performed to detect NHEJ mutations in the nontargeted allele of single-allele AAVS1 HR-targeted iPSC clones. Genomic DNA from selected clones was amplified by PCR using the primers spanning the AAVS1 ZFN target site that would generate a 1.7-bp fragment from the unaltered wild-type (WT) allele but a 2.4-bp fragment from the AAVS1 modified allele. PCR amplification using Taq DNA polymerase with short elongation time (72°C, 30 seconds) was used to selectively amplify the unaltered WT allele and produce the 1.7-bp band only. These PCR products were subsequently purified and sequenced. To detect NHEJ mutations in the putative off-target genomic sites for the AAVS1 ZFNs that had been previously identified by SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential) enrichment [14], the off-target sites were amplified using platinum high-fidelity Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) for 35 cycles of amplification using the primer sets previously published [14]. PCR products were subsequently purified and sequenced.

Cre Recombinase-Mediated Cassette Exchange in iPSCs

For Cre recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (Cre-RMCE), 2 × 106 iPSCs cultured on Matrigel (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, http://www.bd.com) in mTeSR1 medium (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada, http://www.stemcell.com) were transduced with BV-Cre at an MOI of 100 pfu per cell. Twenty-four hours later the medium was changed and cells were again transduced with BV-mCherry at an MOI of 100 pfu per cell. Each colony was transferred to a single well of a Matrigel-coated six-well plate and allowed to undergo clonal expansion through hygromycin B selection (25 μg/ml; AG Scientific, San Diego, CA, http://www.agscientific.com) in mTeSR1 medium.

Results

BV-ZFN Dose Selection for Safety and Efficiency

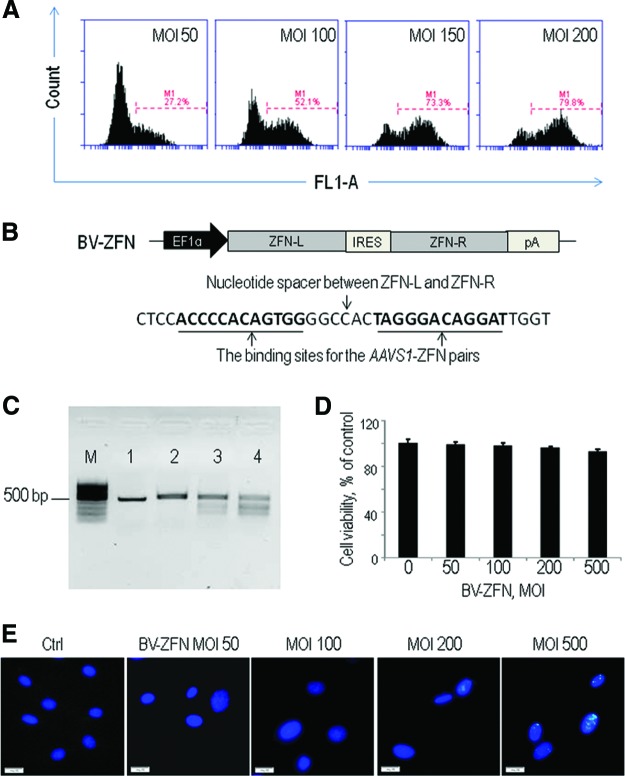

To explore the feasibility of using BV vectors to express ZFNs for targeted insertion of a reprogramming cassette in HFFs, we first tested transduction efficiency of a BV vector carrying the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene under the control of the EF1α promoter. Our previous studies have demonstrated that the activity of this promoter is much stronger than that provided by the Oct4 or cytomegalovirus promoter in human pluripotent stem cells [19, 20], which could be important in generating fully reprogrammed human iPSCs. We observed 80% of HFFs were transduced by the baculoviral vector at an MOI of 200 pfu per cell on day 2 post-transduction (Fig. 1A). The percentage decreased to 50% when an MOI of 100 pfu per cell was used. The EGFP expression dropped quickly within several days and became almost undetectable by day 7.

Figure 1.

BV transduction efficiency and potential cytotoxic effects of BV-ZFN in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs). (A): Transduction efficiency of a BV vector with the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene under the control of the EF1α promoter. HFFs were transduced at an MOI as indicated and subjected to flow cytometric analysis on day 2 post-transduction. (B): Schematic representation of the BV-ZFN construct and the DNA binding sites for the AAVS1-ZFN pairs. (C): Target gene disruption by BV-ZFN. The lower migrating bands indicate the ZFN-mediated gene disruption. Lane 1, genomic DNA (gDNA) from control cells, before annealing; lane 2, gDNA from control cells, after annealing, with T7E1 endonuclease (T7E1); lane 3, gDNA from cells treated with BV-ZFN at MOI 200, after annealing, with T7E1; lane 4, gDNA from cells treated with BV-ZFN at MOI 400, after annealing, with T7E1. (D): Cell viability assay. ZFN-related cytotoxicity was analyzed by measurement of cell viability in 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium assay. HFFs were transduced with BV-ZFN at an indicated MOI overnight, and the assay was performed 3 days later. (E): Immunostaining of BV-ZFN-transduced HFF using anti-γH2AX to assess nuclease-associated genome toxicity. The cells were transduced with BV-ZFN at the indicated MOI overnight and staining was performed 3 days later. Scale bars = 20 μm. Abbreviations: BV, baculovirus; Ctrl, control; EF1α, elongation factor 1α; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; M, molecular marker; MOI, multiplicity of infection; pA, pA, poly(A) tail; ZFN, zinc-finger nuclease; ZFN-L, left homologous arm of ZFN; ZFN-R, right homologous arm of ZFN.

We then generated a BV vector, BV-ZFN, carrying the ZFN genes encoding chimeric proteins consisting of AAVS1-specific DNA binding zinc fingers fused to the nonspecific cleaving endonuclease FokI (Fig. 1B). To confirm the ZFN-induced cleavage at the target AAVS1 site by BV-ZFN, the mismatch-sensitive nuclease assay using the T7E1 nuclease was performed on genomic DNA from HEK293 cells transduced with the virus. As shown in Figure 1C, a significantly portion of the targeted DNA collected from the BV-ZFN-treated cells was digested into two small fragments, approximately 290 and 180 bp, respectively, and the disruption efficiency positively correlated to the virus MOI, demonstrating that BV-ZFN could induce DSBs at AAVS1 in human genome.

Since ZFN-mediated gene editing is based on DNA DSB-stimulated HR, we assessed genome toxicity associated with ZFN-induced DSBs, which might occur when high levels of ZFNs are expressed following high-efficiency baculoviral transduction in human cells. We transduced HFFs using BV-ZFN alone without donor DNA. Cell viability assay revealed an increase in cell death, although not statistically significant, only after BV dose increased to an MOI of 500 (Fig. 1D). We further analyzed the cells using a well-validated assay with antibody against phosphorylated γ-H2AX to visualize DNA DSBs. Phosphorylated γ-H2AX is generated in response to DNA damage and forms foci at DSBs [17, 18]. As revealed by immunofluorescence cell staining, BV-ZFN at an MOI of 100 or lower did not induce detectable phosphorylated γ-H2AX foci in HFFs. Transduction of BV-ZFN at an MOI of 200 or higher was associated with an elevated level of γ-H2AX expression (Fig. 1E). Based on these findings, transduction using BV-ZFN at an MOI of 50 or 100 pfu per cell was selected for the following studies.

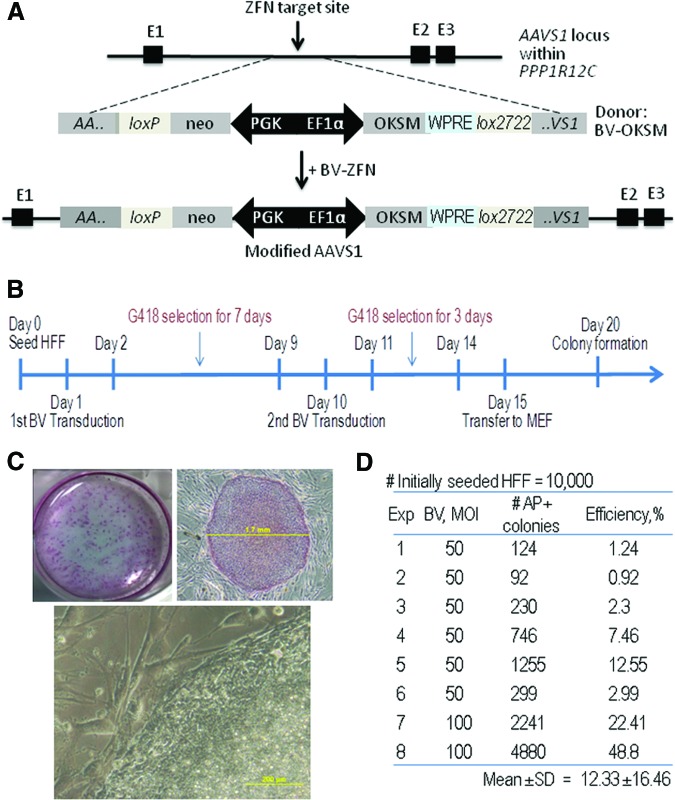

iPSC Generation by Cotransduction with BV-ZFN and BV-OKSM

For cell reprogramming, we generated another BV vector, BV-OKSM, with an expression cassette carrying human Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-myc genes joined with self-cleaving 2A sequence and IRES as a fusion gene and flanked on both sides by sequences homologous to the AAVS1 locus (Fig. 2A). This BV vector was used as a donor vector together with BV-ZFN to reprogram HFFs into iPSCs according to the protocol summarized in Figure 2B. Following the transfer of the transduced cells to the MEF feeder layer on day 15 post-transduction, formation of early colonies could be observed around day 20. The colonies displayed compact cell morphology with sharp borders and were positive for AP staining (Fig. 2C). We observed a very high reprogramming efficiency, as evidenced by obtaining up to 4,880 putative colonies out of 10,000 HFFs when BV-ZFN and BV-OKSM at an MOI of 100 each were used. The mean reprogramming efficiency value of eight individual experiments was 12% (Fig. 2D). BV-OKSM transduction alone or cotransfection of HFFs with pFB-ZFN and pFB-OKSM did not generate any colonies.

Figure 2.

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation by BV transduction-based ZFN technology. (A): Schematics for AAVS1 within the PPP1R12C gene, the BV-OKSM donor construct, the cutting site of BV-ZFN, and the modified AAVS1 following homologous recombination. (B): Schematic overview of the reprogramming protocol used. HFFs were plated at day 0 and transduced at day 1. The transduced cells were cultured under G418 selection for 7 days. The second BV transduction was performed on day 10. The single-cell suspension was plated onto MEF monolayer on day 15. By day 20, compact adherent colonies were observed already. (C): Images of iPSC colonies. Top left: Example of one well of colonies in a six-well plate stained for alkaline phosphatase (AP) on day 20. HFFs were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. The overwhelming majority of colonies clearly stained positive for AP. Top right: An AP-stained colony with typical compact morphology on day 25. Scale bar = 1.7 mm. Bottom: High-magnification view of the edge of a colony. Scale bar = 200 μm. (D): AP-positive colony forming efficiency. Eight experiments were performed, and their results are listed. Abbreviations: BV, baculovirus; E, exon; EF1α, elongation factor 1α; Exp, experiment; HFF, human foreskin fibroblast; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; MOI, multiplicity of infection; OKSM, Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-myc; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element; ZFN, zinc-finger nuclease.

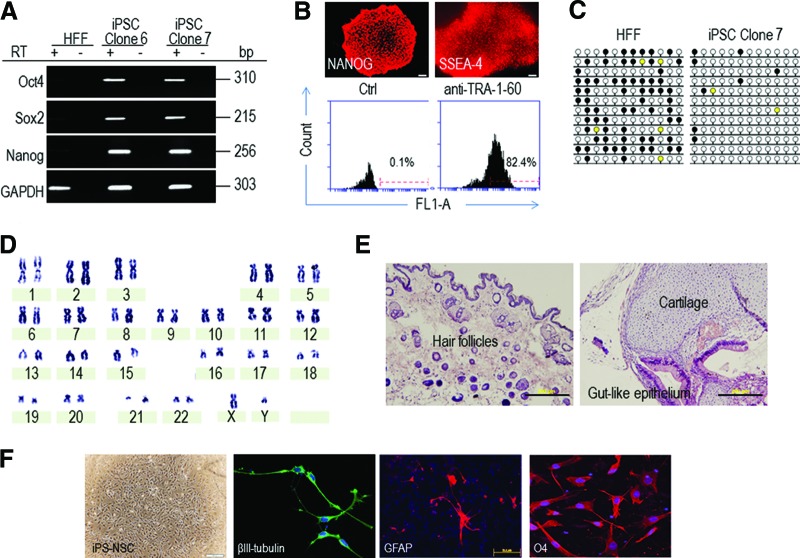

Colonies with observable outgrowth were selected between days 20 and 30 for clonal expansion on either MEF feeder layer in iPSC medium or feeder-free Matrigel in mTeSR medium. The generated clones exhibited morphology resembling human ESC colonies with small round cells containing large nuclei (Fig. 2C) and expressed classic ESC markers as evidenced by RT-PCR analysis, immunostaining, and flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 3A, 3B). The Oct4, Nanog, and Rex1 promoter regions were demethylated in iPSCs (Fig. 3C; supplemental online Fig. 1). Karyotyping analysis of iPSCs demonstrated that there was no numerical or structural aberration and the cells retained a normal karyotype (Fig. 3D). When iPSCs were seeded in an ultra-low-attachment plate and cultured in an EB differentiation medium, spherical EB aggregates were formed spontaneously, which expressed markers for all three germ layers (supplemental online Fig. 2). To further examine their differentiation potential, iPSCs were injected into the hind legs of NOD/SCID mice to form teratomas. The teratomas became apparent 6–8 weeks after injection. Differentiation profiles of the resulting teratomas were then assessed by histological examination. Figure 3E demonstrates the presence of cells from all three embryonic germ layers in a teratoma, confirming the pluripotency of the generated iPSCs. iPSCs could also differentiate into NSCs in a defined culture condition containing basic fibroblast growth factor and epidermal growth factor. The generated NSCs expressed neural stem/precursor cell markers, including CD133, Nestin, Pax6, Sox1, and Sox2, and were able to form neurospheres when transferred to suspension culture in a low-cell-binding plate (data not shown). Importantly, these cells displayed the functional hallmark of NSCs: differentiation into β3-tubulin-positive neurons, glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive astrocytes, and O4-positive oligodendrocytes (Fig. 3F). These results demonstrated that HFFs were indeed reprogrammed into iPSCs by our BV transduction-based ZFN technology.

Figure 3.

Characterization of iPSCs generated. (A): Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of molecular marker expression in HFFs and two iPSC clones. Expression of pluripotent marker genes Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog was detected in iPSCs but not in HFFs. GAPDH was included as a loading control. (B): Pluripotent stem cell marker expression. Top: Immunocytochemical staining of NANOG and SSEA-4. Scale bar = 200 μm. Bottom: Flow cytometric analysis for cell surface marker TRA-1-60 expression on iPSCs. (C): DNA methylation of the Oct4 promoter region analyzed by bisulfite sequencing. Black and white circles indicate methylated and unmethylated CpG dinucleotides, respectively. Yellow circles, unknown. (D): G-banding karyotype analysis of iPSCs shows a normal karyotype. (E): Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue sections of a teratoma formed by iPSCs. The histology of differentiated tissues found in the teratoma demonstrates hair follicles (ectoderm), cartilage (mesoderm), and gut-like epithelium (endoderm). Scale bars = 200 μm. (F): Characterization of iPS-NSCs. Immunocytochemistry analysis of the multipotency of derived NSCs. When cultured under defined conditions, NSCs differentiated into β3-tubulin-positive neurons, GFAP-positive astrocytes, and O4-positive oligodendrocytes. Scale bars = 100 μm. Abbreviations: GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; HFF, human foreskin fibroblast; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; iPS-NSC, induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cell; +RT, with reverse transcriptase; −RT, without reverse transcriptase.

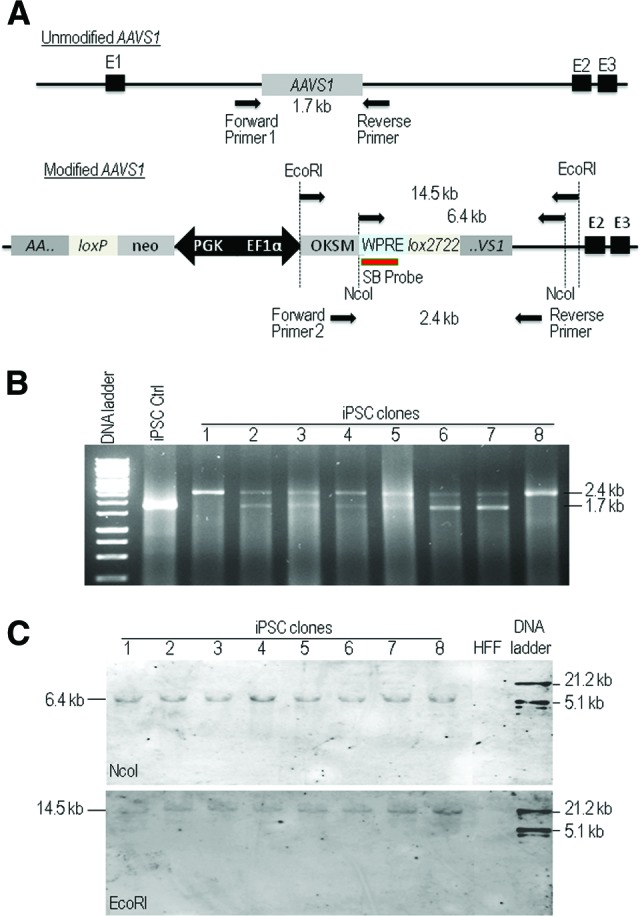

Genetic Characterization to Confirm AAVS1-Specific Integration and No NHEJ Mutations

We then performed PCR genotyping in 20 iPSC clones randomly selected from different experiments. The genomic DNA of these clones was extracted and subjected to PCR amplification by using two pairs of PCR primers designed as indicated in Figure 4A. One single 2.4-kb band indicates the presence of biallelically modified AAVS1 sites, whereas the presence of both 1.7-kb and 2.4-kb fragments indicates monoallelic disruption of the AAVS1 locus. We observed that all 20 clones contained the site-specific integration of the OKSM cassette within the AAVS1 locus, four of which were biallelically modified (Fig. 4B; supplemental online Fig. 3). For further confirmation and also to verify the possible existence of multiple transgene copies, Southern blot analysis was carried out on eight iPSC clones using a probe specific for the WPRE element of the OKSM cassette after genomic DNA digestion with NcoI or EcoRI. The detection of single 6.3-kb and 14.5-kb fragments in all these clones after NcoI and EcoRI digestion, respectively, and the absence of the fragments in parental HFFs demonstrated integration of the OKSM cassette into a single genomic site in the iPSCs (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

The AAVS1 locus-specific integration of the reprogramming factors. (A): Schematic representation to show the positions for primers used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping and the probe for Southern blot analysis. Using PCR forward primer 1 and reverse primer 1 will form a 1.7-kb fragment for detection of unmodified AAVS1, and using the PCR forward primer 2 and reverse primer 2 for detection of a 2.4-kb fragment for 3′-modified AAVS1. The coamplification of the 1.7- and 2.4-kb fragments is used to identify mono- and biallelic modification at the AAVS1 locus. The SB probe is the probe binding site used for Southern blot analysis of NcoI-digested or EcoRI-digested genomic DNA to detect a 6.4-kb or 14.5-kb fragment, respectively. (B): PCR analysis of genomic DNA to detect mono- and biallelic modification at the AAVS1 locus in iPSC clones. One single 2.4-kb band in clones 1 and 8 indicates the presence of biallelically modified AAVS1 sites, whereas the presence of both 1.7-kb and 2.4-kb fragments in the rest clones indicates monoallelic disruption of the AAVS1 locus. An OKSM lentiviral vector-generated iPSC clone is included as a negative control. (C): Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA collected from eight iPSC clones for detection of modified AAVS1. Genomic DNA was digested with NcoI or EcoRI and hybridized with a DIG-labeled probe as shown in (A). HFF genomic DNA was included as a negative control. Abbreviations: Ctrl, control; EF1α, elongation factor 1α; HFF, human foreskin fibroblasts; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; OKSM, Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-myc; SB, Southern blot; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element.

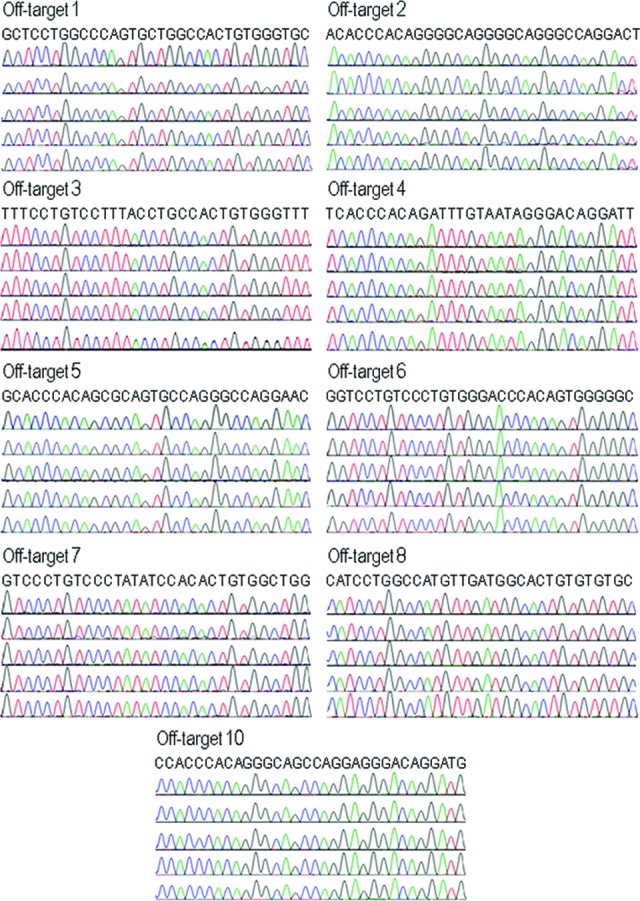

In addition to resulting in homologous recombination with donor DNA, DNA double-strand cleavage induced by ZFNs can also be repaired by NHEJ without the involvement of a homologous template, which can maintain the wild-type sequence, or introduce loss or gain in base pairs. We performed DNA sequencing in 10 monoallelically modified iPSC clones to determine the frequency of NHEJ mutations at the putative wild-type AAVS1 locus on the remaining allele without the OKSM cassette integration and observed that all these sites were wild-type (supplemental online Fig. 4). A potential limitation of the ZFN technology is the induction of off-target DNA breaks at related sequences throughout the genome. Using SELEX, 10 most probable off-target cleavage sites for the AAVS1 ZFNs have been identified on a genome-wide basis and 9 of them can be amplified by PCR to examine NHEJ mutations [14]. We amplified these nine SELEX-predicted genomic off-target sites from genomic DNA isolated from HFFs and four AAVS1-targeted iPSC clones generated in this study for DNA sequencing. Since the PCR products were from a homogeneous cell population in each iPSC clone, mutations in the off-target sequence will show as single or double peaks that are different from reference sequence. DNA sequencing of the PCR products revealed no evidence of deletions or insertions at these off-target sites and all sites were wide type (Fig. 5). Thus, cotransduction with BV-ZFN and BV-OKSM resulted in the targeted addition of the OKSM cassette into the genomic ZFN target site with high efficiency and specificity.

Figure 5.

Analysis of nonhomologous end joining mutations at nine SELEX-predicted genomic off-target sites for the AAVS1 zinc-finger nucleases. These nine sites were previously identified by SELEX and examined by Hockemeyer et al. [14]. The genomic off-target sites were amplified from genomic DNA isolated from human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) and four AAVS1-targeted induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) clones generated in this study. DNA sequencing results from HFFs (top chromatograph) and iPSC clones are presented. The reference sequence for each site is listed at the top.

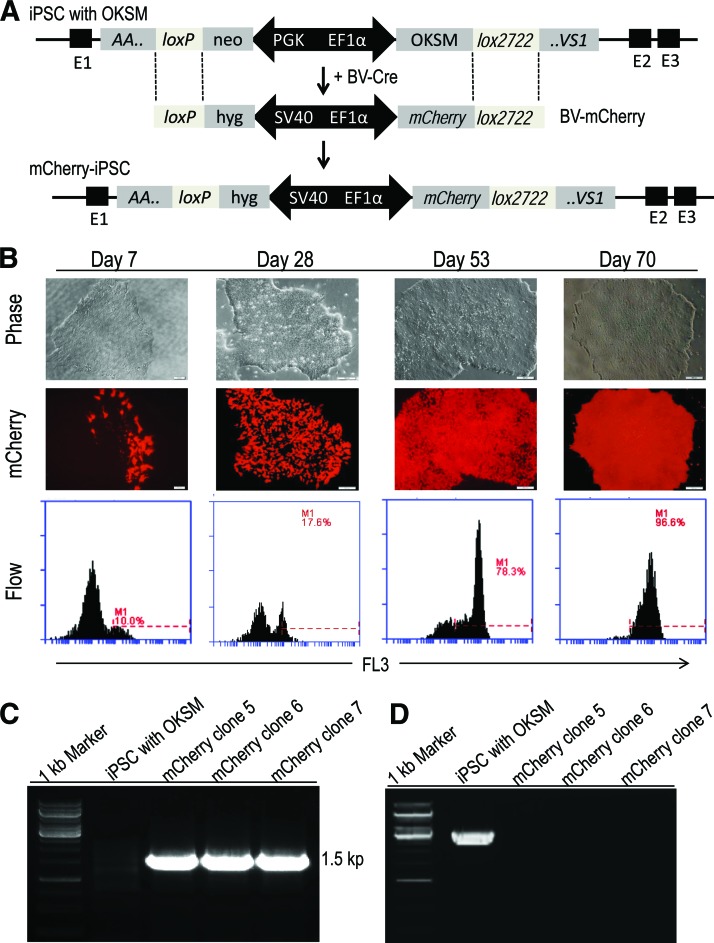

Replacing the OKSM Cassette With an mCherry Expression Cassette at AAVS1 via BV Transduction-Based, Cre Recombinase-Mediated Cassette Exchange

Removal of exogenous OKSM reprogramming genes can increase the capacity of iPSCs to undergo directed differentiation [21] and is required for therapeutic applications of iPSC-derived cells. On the other hand, medical applications of iPSC-derived cells could be augmented by ectopic expression of a therapeutic gene. To test the possibility of achieving the two purposes simultaneously, we have included heterospecific loxP sites to flank the expression cassette of BV-OKSM (Fig. 2A) in order to perform Cre-RMCE after iPSC generation. In Cre-RMCE, Cre recombinases target preintroduced loxP sites and exchange a genomic fragment flanked by a pair of heterospecific loxP sequences for a floxed transgene expression cassette (flanked by the same heterospecific loxP sequences) in a donor vector. We have previously adopted a two-step genetic modification process using conventional HR followed by Cre-RMCE to direct transgene integration into the AAVS1 locus in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and demonstrated that BV transduction is efficient in supporting RMCE-mediated integration of a transgene expression cassette into a target site embedded into the hESC genome [16]. As a proof-of-principle demonstration, we tested in the present study whether BV transduction-based Cre-RMCE (BV-RMCE) could be used to replace the OKSM cassette with an mCherry expression cassette.

We used two BV vectors, BV-Cre and BV-mCherry, for this test. BV-mCherry contains a floxed BV-mCherry gene under the control of the EF1α promoter and the hygromycin resistance gene under the control of the simian virus 40 promoter (Fig. 6A). After cotransduction of iPSCs generated by our BV transduction-based ZFN technology with BV-Cre and BV-mCherry, the cells were subjected to hygromycin selection for 4 weeks. Colonies with mCherry-positive cells were subjected to mechanical selection at the time for normal subculture and further expanded under hygromycin selection until almost all iPSCs became mCherry-positive. Pure mCherry-positive clones were usually obtained after 10 weeks (Fig. 6B). The genomic DNA of the selected mCherry-positive iPSC clones was extracted and subjected to PCR genotyping using a primer specific for the chromosome 19 and a primer specific for the mCherry gene. The amplification of a 1.5-kb fragment indicated the successful transgene exchange and integration of the mCherry gene into the AAVS1 site via BV-RMCE (Fig. 6C). Using another pair of PCR primers specific for the chromosome 19 and for the OKSM reprogramming cassette, we confirmed that the reprogramming cassette was successfully removed, thus producing iPSCs free of exogenous reprogramming factors (Fig. 6D). The selected mCherry iPSC clones maintained a pluripotent state, as indicated by the expression of the pluripotent markers SOX2, OCT4, NANOG, SSEA-4, and TRA-1-60 and their differentiation ability to form EBs and express marker genes for three germ layers (supplemental online Fig. 5A–5D). We further performed real-time RT-PCR analysis to quantify the expression levels of exogenous Oct4 and Sox2 before and after the excision of the OKSM cassette in iPSCs and iPSC-derived EBs. We detected high expression levels of exogenous Oct4 and Sox2 in both iPSCs and EBs with the OSKM cassette and no expression in iPSCs and EBs without OSKM, demonstrating that the genes in the integrated OSKM cassette were not silenced and retained expression even after differentiation into EBs (supplemental online Fig. 5E).

Figure 6.

BV transduction-based Cre recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (BV-RMCE) to replace the OKSM reprogramming factor genes with the gene encoding mCherry in iPSCs generated by BV transduction-based zinc-finger nuclease technology. (A): Schematic representation of replacing the reprogramming factor genes (4F) with the mCherry gene through BV-RMCE at the AAVS1 locus. Both constructs were flanked by the same heterospecific loxP sequences that permit cassette exchange in the presence of Cre recombinase expressed from BV-Cre. (B): Phase contrast and fluorescence imaging to show the increase in mCherry expression under hygromycin selection at different interval of times following Cre recombinase-mediated cassette exchange. Scale bars = 200 μm. Bottom: Quantitative flow cytometric analysis. (C): Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping to confirm AAVS1 integration of the mCherry cassette. A primer specific for the mCherry gene and a primer specific for chromosome 19 downstream of the 3′-end of the right AAVS1 homologous arm were used. The amplification of a 1.5-kb fragment demonstrates the successful cassette exchange at AAVS1 through BV-RMCE. (D): PCR analysis of genomic DNA collected from iPSC clones to confirm the removal of the reprogramming factor genes by the AAVS1-targeted cassette exchange. Abbreviations: BV, baculovirus; EF1α, elongation factor 1α; hyg, hygromycin; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; neo, neomycin; OKSM, Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, and c-myc; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; SV40, simian virus 40.

Discussion

Genome insertion of reprogramming factor genes significantly improves the efficiency of human iPSC derivation. Thus, iPSC generation using phage integrase-mediated nonrandom integration has been tested, providing efficiency comparable with that offered by retroviral approaches [22, 23]. iPSCs can also be generated using PiggyBac and Sleeping Beauty transposons that induce stable genome modification [24, 25]. However, because of the nontargeted gene transfer nature of these systems, the site of transgene insertion cannot be prechosen. This can possibly lead to undesirable insertional mutagenesis or poor expression of the integrated gene if the insertion occurs in a region of heterochromatin. ZFN systems can target preselected genomic sites and hence are attractive in introducing expression cassettes specifically into already identified safe harbors, where the insertion into the genome is theoretically less genotoxic and exogenous DNA can be expressed stably.

A recently published study reported by Ramalingam et al. [10] used a transfection reagent to deliver ZFNs and a donor plasmid into human primary cells for targeted insertion of reprogramming factor genes into the CCR5 locus, and has shown a reprogramming efficiency of 0.04%. To explore the full potential of ZFN-mediated genetic manipulation in iPSC generation, we tested BV transduction-based codelivery of ZFNs and a reprogramming cassette. A BV transduction system containing a polycistronic reprogramming factor expression cassette was tested previously to produce iPSCs from mouse embryonic fibroblasts [26]. The system used the transient transduction nature of BV vectors, and the highest efficiency of iPSC production in their study was 0.006%. By combining powerful cell transduction efficiency offered by baculoviral vectors with the site-specific targeting property provided by ZFN technology to insert reprogramming factor genes into a favorable transgene expression site, we observed a high reprogramming efficiency of 12% (the mean value of eight individual experiments) in the current study, much higher than the previously reported efficiencies between 0.001% and 1% [27]. The highest reprogramming efficiency obtained was 4,880 AP-positive colonies generated from 10,000 HFFs. Since the transduction efficiency in HFFs was 50% for the BV dose used, 48.8% iPSC derivation efficiency indicates that almost all transduced HFFs were reprogrammed. This is strictly in contrast to the previous observation that less than 3% of somatic cells expressing OKSM give rise to iPSC colonies in general [28]. A recent study has demonstrated that iPSC formation follows an early and late deterministic phase and expression of OKSM again in a late stage of reprogramming can significantly improve cell ability to form iPSCs [28]. In agreement, we transduced HFFs twice, on day 1 and day 10, to generate more AP-positive iPSC colonies. When genome toxicity associated with different dosages of BV-ZFN was evaluated, we observed detectable phosphorylated γ-H2AX foci only when an MOI of 200 or above was used. Our observation of no observed NHEJ DNA mutations in examined AAVS1-targeted iPSC clones further supports the notion that the dose of BV-ZFN used in the current study (MOI = 50–100) was not only efficient in assisting iPSC generation but also safe.

The use of BV vectors for ZFN-mediated targeted gene insertion is justified by several factors. First, BVs replicate in insect cells but become replication-incompetent in mammalian cells, a property that makes recombinant BV vectors easy to produce and far less harmful to humans [11, 12]. When used for genetic modification of human cells, BV vectors mediate transient transgene expression without integration into the host genome. This feature suits the purpose of temporary transgene expression well. In the context of ZFN-mediated genetic engineering, only transient expression of the nuclease is required, as the persistent nuclease expression or continual enzymatic activity could lead to genomic instability and be harmful to cells. Second, BV vectors hold large gene cloning capacity and can be used to transfer large (at least 100 kb) and multiple DNA inserts [11, 12]. The basic design of ZFNs requires the coexpression of at least two different monomers in the same target cell. The simultaneous expression of two ZFN monomers can be achieved by direct gene transfer of two independent ZFN expression vectors, which could present a technical bottleneck for the expansion of this ZFN technology to some cell types that are difficult to be transfected or transduced. The large cloning capacity of BV vectors enables easy cloning and expression of two ZFN monomers in one single BV vector after separating independent ZFN-coding sequences by self-cleaving 2A sequence or IRES. Indeed in a recent publication reporting the use of a nonintegrating BV vector system for gene editing at the CCR5 locus in hESCs, both ZFN monomers and the donor DNA are delivered from a single combined BV vector [29]. Third, during the generation of ZFN-expressing viral vectors designed for mammalian cell gene targeting, ZFN-mediated toxicity reduces lentivirus production in lentiviral vector-producing HEK293T human embryonic kidney cells, but no such toxicity was observed when BV-ZFN was produced in BV-producing Sf9 insect cells [29]. Therefore, BV transduction offers unique advantages to iPSC generation by ZFN technology.

For the medical applications that use differentiated progeny of iPSCs as transplantable cells for tissue engineering or regeneration, constant and steady expression of transgenes can be beneficial for enhancing the functions of the transplanted cells. Progenies derived from genetically modified iPSCs can also be used for gene therapy purpose to deliver therapeutic gene products. For example, tumor-tropic neural stem cells or mesenchymal stem cells can be derived from genetically engineered human pluripotent stem cells and used for tumor-targeted gene therapy [30, 31, 32]. In the current study, when ZFN technology was used to insert reprogramming factor genes for iPSC generation, we also introduced mutually incompatible, heterospecific loxP sites into the AAVS1 locus. The generated iPSC clones are single-cell-derived clones harboring a single copy of a floxed expression cassette integrated at a favorable genomic site. These iPSCs can be used as a master cell line, in which Cre-RMCE can be used not only to remove the exogenous reprogramming factor genes but also readily add different floxed transgenes into the predefined AAVS1 site without disruptive genomic modification. As demonstrated in this study, Cre-RMCE can be performed efficiently by using two baculoviral vectors, one acting as a transgene donor and another as source of Cre expression, without affecting pluripotency of iPSCs. This Cre-RMCE strategy can be adopted to build versatile transgenic iPSCs with inducible transgene expression, lineage-specific reporter and constitutive functional gene expression, as already tried in human ESCs [33]. Its potential in allowing repeatable yet accurate insertion of different transgene cassettes into a predefined genomic site in a master iPSC line for homogeneous transgene expression is well worth exploring further.

Conclusion

We have developed a novel BV-ZFN technology for permanent genome modification by transient BV vectors and used the technology to generate genetically amenable human iPSCs. Our approach is efficient in generating iPSCs and flexible for further genetic modification in the generated pluripotent stem cells, thus providing an attractive alternative to current iPSC techniques.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health's National Medical Research Council (NMRC/1284/2011), the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE2011-T2-1-056), and the Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology (Biomedical Research Council, Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore).

Author Contributions

R.-Z.P., F.C.T., S.-L.G., C.-H.L., and H.Z.: collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; W.-K.T., Q.L., and C.C.: collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; S.D., Z.L., J.C.-K.T., C.W., and J.Z.: collection and assembly of data; W.F. and H.C.T.: conception and design; S.W.: conception and design, financial support, administrative support, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Robinton DA, Daley GQ. The promise of induced pluripotent stem cells in research and therapy. Nature. 2012;481:295–305. doi: 10.1038/nature10761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharkis SJ, Jones RJ, Civin C, et al. Pluripotent stem cell-based cancer therapy: Promise and challenges. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:127ps9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schröder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, et al. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell. 2002;110:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collin J, Lako M, et al. Robust, persistent transgene expression in human embryonic stem cells is achieved with AAVS1-targeted integration. Stem Cells. 2008;26:496–504. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schambach A, Baum C. Clinical application of lentiviral vectors: Concepts and practice. Curr Gene Ther. 2008;8:474–482. doi: 10.2174/156652308786848049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palpant NJ, Dudzinski D. Zinc finger nucleases: Looking toward translation. Gene Ther. 2013;20:121–127. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collin J, Lako M. Concise review: Putting a finger on stem cell biology: Zinc finger nuclease-driven targeted genetic editing in human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1021–1033. doi: 10.1002/stem.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng LT, Sun LT, Tada T. Genome editing in induced pluripotent stem cells. Genes Cells. 2012;17:431–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2012.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramalingam S, London V, Kandavelou K, et al. Generation and genetic engineering of human induced pluripotent stem cells using designed zinc finger nucleases. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:595–610. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kost TA, Condreay JP, Jarvis DL. Baculovirus as versatile vectors for protein expression in insect and mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:567–575. doi: 10.1038/nbt1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CY, Lin CY, Chen GY, et al. Baculovirus as a gene delivery vector: Recent understandings of molecular alterations in transduced cells and latest applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2011;29:618–631. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeKelver RC, Choi VM, Moehle EA, et al. Functional genomics, proteomics, and regulatory DNA analysis in isogenic settings using zinc finger nuclease-driven transgenesis into a safe harbor locus in the human genome. Genome Res. 2010;20:1133–1142. doi: 10.1101/gr.106773.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hockemeyer D, Soldner F, Beard C, et al. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:851–857. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller JC, et al. An improved zinc-finger nuclease architecture for highly specific genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:778–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramachandra CJ, Shahbazi M, Kwang TW, et al. Efficient recombinase-mediated cassette exchange at the AAVS1 locus in human embryonic stem cells using baculoviral vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e107. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, et al. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogakou EP, Boon C, Redon C, et al. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905–915. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng J, Du J, Zhao Y, et al. Baculoviral vector-mediated transient and stable transgene expression in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1055–1061. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du J, Zeng J, Zhao Y, et al. The combined use of viral transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory elements to improve baculovirus-mediated transient gene expression in human embryonic stem cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2010;109:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sommer CA, Sommer AG, Longmire TA, et al. Excision of reprogramming transgenes improves the differentiation potential of iPS cells generated with a single excisable vector. Stem Cells. 2010;28:64–74. doi: 10.1002/stem.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye L, Chang JC, Lin C, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using site-specific integration with phage integrase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19467–19472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012677107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karow M, Chavez CL, Farruggio AP, et al. Site-specific recombinase strategy to create induced pluripotent stem cells efficiently with plasmid DNA. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1696–1704. doi: 10.1002/stem.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, et al. piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grabundzija I, Wang J, Sebe A, et al. Sleeping Beauty transposon-based system for cellular reprogramming and targeted gene insertion in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1829–1847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takata Y, Kishine H, Sone T, et al. Generation of iPS cells using a BacMam multigene expression system. Cell Struct Funct. 2011;36:209–222. doi: 10.1247/csf.11008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.González F, Boué S, Izpisúa Belmonte JC. Methods for making induced pluripotent stem cells: Reprogramming à la carte. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:231–242. doi: 10.1038/nrg2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polo JM, Anderssen E, Walsh RM, et al. A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell. 2012;151:1617–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lei Y, Lee CL, Joo KI, et al. Gene editing of human embryonic stem cells via an engineered baculoviral vector carrying zinc-finger nucleases. Mol Ther. 2011;19:942–950. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bak XY, Lam DH, Yang J, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells as cellular delivery vehicles for prodrug gene therapy of glioblastoma. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:1365–1377. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Y, Lam DH, Yang J, et al. Targeted suicide gene therapy for glioma using human embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells genetically modified by baculoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2012;19:189–200. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, Lam DH, Goh SS, et al. Tumor tropism of intravenously injected human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cells and their gene therapy application in a metastatic breast cancer model. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1021–1029. doi: 10.1002/stem.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du ZW, Hu BY, Ayala M, et al. Cre recombination-mediated cassette exchange for building versatile transgenic human embryonic stem cells lines. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1032–1041. doi: 10.1002/stem.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.