Abstract

Purpose

To study the prevalence, manifestations and severity of ocular involvement of Behçet’s disease in Jordanian patients.

Methods

The study population consisted of 43 patients diagnosed to have Behçet’s disease through Rheumatologist’s examinations conducted at Jordan University Hospital between January 2002 and July 2009. The sample involved patients who displayed ocular manifestations. This included 18 patients; 12 males and 6 females with a mean age of 35 years (SD = 17.26). Ophthalmological examinations and retrospective analysis of medical files were carried on.

Results

Ocular manifestations were seen in 41.9% of patients. The most common manifestation for Behçet’s disease was vitritis with a prevalence of 55.6%, followed by anterior uveitis and retinal vasculitis (50% for each). On the other hand, the most frequent complications involved were cataract, cystoid macular edema (CMO), posterior synechiae and glaucoma with a prevalence of (44.4%), (33.3%), (11.1%) and (5.6%), respectively.

Conclusion

The prevalence and severity of ocular lesions in Behçet’s disease is relatively low in Jordanian patients. This result indicates that early diagnoses and intervention might delay or even prevent vision loss for those patients.

Keywords: Behçet’s disease, Ocular manifestation, Behcet’s complications

Introduction

Behçet’s disease is a chronic, recurrent, multisystem, autoimmune disorder of unknown etiology. This disease is characterized by the triad of oral ulcers, genital ulcers, and ocular lesions.

In 1937 Dr. Hulusi Behçet, a Turkish Dermatology professor described the triple symptom complex of recurrent oral ulcers, genital ulcers and iritis as a distinct entity. Professor Behçet did not associate the disease with any known etiology, but blamed unknown virus.1

Several sets of diagnostic criteria had been in use until 1990 when the International Study Group (ISG) for Behcet’s disease proposed a new set of criteria.2 The ISG requires recurrent oral ulcers as a mandatory criterion plus two of four criteria, including recurrent genital ulcers, skin lesions, uveitis and a positive pathergy test.3

Behcet’s disease has a worldwide distribution, being more common among populations with a higher prevalence of HLA B5 and its split, HLA B 51, in the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East and Far East.4

The etiopathogenesis of the disease is still unknown. It is thought that in genetically susceptible individuals there is an enhanced nonspecific inflammatory response, evident as a skin pathergy reaction. Environmental triggers most probably microbial antigens, induce an antigen-driven specific inflammatory response superimposed on this hyperreactivity. This leads to endothelial dysfunction and occlusive vasculopathy that may affect all types and sizes of vessels in the body.5

Our study aims to identify ocular manifestations and their severity in Jordanian patients with Behçet’s disease.

Methods

Participants

The Ethics board at Jordan University Hospital approved a retrospective chart review for 43 patients diagnosed with Behçet’s disease. Those patients were diagnosed by the Rheumatology Department and then referred to the Ophthalmology Department in the period between January 2002 and July 2009. Male cases accounted for the majority with 29 patients representing (67.4%) of Behcet’s disease population at Jordan University Hospital. Meanwhile, the number of female patients reached 14 with a percentage of (32.6%). Patients aged between 1 and 72 years with a mean age of 36.88 (SD = 13.85). A review of medical profiles reported 10.79 years (SD = 9.11) as a mean duration of the disease.

Materials

Comprehensive ophthalmological evaluations were conducted including assessment of visual acuity, external ocular examination, slit lamp biomicroscopy and a detailed fundus examination. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured using an applanation tonometer.

Results

According to Rheumatologist diagnoses at Jordan University Hospital; a total of 43 patients were identified with Behçet’s disease between January 2002 and July 2009. This included 29 males and 14 females. Patients’ mean age was 36.88 years (SD = 13.85). The mean duration of the disease was 10.79 years (SD = 9.11).

All patients who displayed ocular manifestations (18) were included in this study. There were 12 males (66.7%) and 6 females (33.3%) with a mean age of 35 years (SD = 17.26). The mean duration of the disease was 9.22 years (SD = 9.95).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 17. Descriptive statistics were presented to describe the distribution of the sample on study variables (Table 1).

Table 1.

The prevalence of Male versus female patients distributed on study variables.

| Ocular manifestation | % (n) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | |

| Extraocular muscle paralysis | 0 | 100% (2) |

| Anterior uvitis | 77.8% (7) | 22.2% (2) |

| Vitritis | 70% (7) | 30% (3) |

| Retinal vasculities (vascular sheathing) | 44.4% (4) | 55.6% (5) |

| Vascular occlusion | 66.7% (2) | 33.3% (1) |

| Multifocal retinitis | 100% (2) | 0 |

| Macular edema especially cystoids type (CMO) | 66.7% (4) | 33.3% (2) |

| Epiretinal membrane (ERM) | 66.7% (4) | 33.3% (2) |

| Retinal atrophy | 0 | 100% (1) |

| Papillitis | 0 | 100% (1) |

| Optic atrophy | 50% (1) | 50% (1) |

| Papildema | 50% (1) | 50% (1) |

| Neovascularization elsewhere (NVE) | 100% (1) | 0 |

Results displayed in Table 2, show that none of the patients manifested signs of recurrent conjunctivitis, conjunctival ulcers, episcleritis, scleritis, filamentary keratitis, marginal sterile corneal ulcers, retinal exudation, exudative retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, neovascular glaucoma or phthisis bulbi.

Table 2.

Distribution of patients on study variables and ocular manifestations.

| Variable | No (n = 18) | % | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.09–1.57 | .000 | ||

| Male | 12 | 66.7 | ||

| Female | 6 | 33.3 | ||

| Age group (Year) | 1.52–2.81 | .000 | ||

| 19–29 | 6 | 33.3 | ||

| 30–39 | 8 | 44.4 | ||

| 40–49 | 1 | 5.6 | ||

| 50–59 | 1 | 5.6 | ||

| 60 & More | 2 | 11.1 | ||

| Duration (Year) | 1.27–.262 | .000 | ||

| 1–5 | 10 | 55.6 | ||

| 6–10 | 5 | 27.8 | ||

| 16–20 | 1 | 5.6 | ||

| +20 | 2 | 11.1 | ||

| Side | 1.57–1.99 | .000 | ||

| Unilateral | 5 | 27.8 | ||

| Bilateral | 13 | 72.2 | ||

| Visual acuity (Snellen chart) | .3746–.7710 | .000 | ||

| 1–0.8 | 9 | 50 | ||

| 0.7–0.5 | 2 | 11.1 | ||

| 0.4–0.2 | 4 | 22.2 | ||

| 0.1 | 1 | 5.6 | ||

| CF to PL | 2 | 11.1 | ||

| Ocular lesions | ||||

| Uveitis | 9 | 50 | .24 to .76 | .001 |

| Vitritis | 10 | 55.6 | .30 to .81 | .000 |

| CRVO | 1 | 5.6 | −.06 to .17 | .331 |

| BRVO | 1 | 5.6 | −.06 to .17 | .331 |

| Neovascularization | 1 | 5.6 | −.06 to .17 | .331 |

| Retinal vasculitis | 9 | 50 | .24 to .76 | .001 |

| Retinal atrophy | 1 | 5.6 | −.06 to .17 | .331 |

| Cranial nerve palsy | 2 | 11.1 | −.05 to .27 | .163 |

| Optic nerve atrophy | 2 | 11.1 | −.05 to −27 | .163 |

| Papillitis | 1 | 5.6 | −.06 to .17 | .331 |

| Papileodema | 1 | 5.6 | −.06 to .17 | .331 |

| Cystoids macular edema | 6 | 33.3 | .09 to .57 | .010 |

| Macular hole | 1 | 5.6 | −.06 to .17 | .331 |

| Cataract | 8 | 44.4 | .19 to .70 | .002 |

| Glaucoma | 1 | 5.6 | −.06 to .17 | .331 |

| Posterior syneachea | 2 | 11.1 | −.05 to .27 | .163 |

Results also suggest that the most common ocular manifestations are vitritis (55.6%), anterior uveitis (50%), and retinal vasculitis (50%). Although higher prevalence was seen among male cases in the first two manifestations (70%) and (77.8%) respectively, nevertheless, lower prevalence for male patients was reported in the third (44.4%).

In addition, findings illustrate an equal prevalence for cystoid macular edema (CMO) and epiretinal membrane (ERM) (33.3%). More males than females were affected 4:2 in both.

Moreover, our results report a low prevalence for retinal vascular occlusion (16.7%). Two males (66.7%) and one female (33.3%) were involved in this manifestation.

Furthermore, an equal percentage of males and females manifested optic atrophy and papilloedema. While two female cases (100%) manifested extraocular muscle paralysis and two males (100%) displayed signs of multifocal retinitis these four manifestations rated a prevalence of two (11.1%) each.

Finally, a single case of retinal atrophy (Fig. 1), papillitis and NVEs (5.6%) was reported. A female patient with the first two manifestations versus male patient with the last (NVEs).

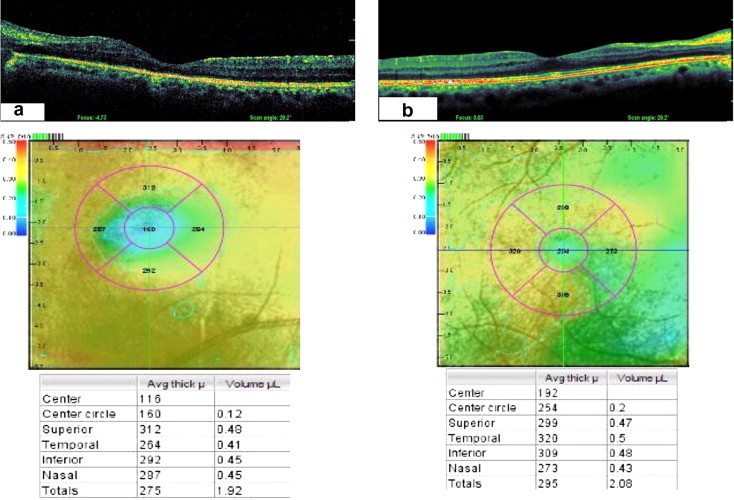

Figure 1.

(a) Left mauclar OCt image shows significant reduction in retinal thickness (160 μ) as compared with OCT image (b) of the right eye (254 μ) in patient with longstanding intraocular inflammation secondary to Behcet’s disease.

Additionally, results also revealed evidence of complications. Cataract was the most frequent complication present in 8 (44.4%) patients, followed by cystoid macular edema in 6 (33.3%) patients, posterior synechiae in 2 (11.1%) patients and glaucoma in 1 (5.6%) patient.

Discussion

Behçet’s disease is a systemic vasculitis involving many organ systems and leading to a wide spectrum of manifestations.6

Research in the medical field has proven that the eye is the most commonly involved vital organ in Behçet’s disease.7,8

This paper aims to address the prevalence and ocular manifestations involved in Behçet’s disease in a Jordanian sample.

Studies conducted in Iran, Japan, China, Korea and Germany (referred to as the five nation’s studies) reported the following percentages of ocular manifestations: (55%), (69%), (35%), (51%) and (55%), respectively.9 A high prevalence of eye involvement has also been reported in Arab countries such as Morocco (67%)10 and Jordan (60%).

In the current study, however, the prevalence was 41.9% which indicates a lower value than what was previously reported in Jordan (60%).11

The male (with Behcet’s disease) to female ratio in our study was 2:1. Different ratios comparing males to females were reported in the five nation’s studies (1.19: 1, 0.98:1, 1.34:1, 0.63:1 and 1.40:1), respectively.9

Although the international study group of Behçet’s Disease has emphasized that the presence of recurrent oral ulcer is the primary consideration in the diagnosis process.12 Others argue that uveitis is the initial manifestation of the disease in 10–20% of patients.13,14 Uveitis is classically defined as a bilateral nongranulomatous panuveitis and retinal vasculitis. However, uveitis may remain unilateral for many years in some patients.15 In the current study we found that all affected females and 75% of affected males had bilateral uveitis. Moreover, none of patients were diagnosed with uveitis as a primary manifestation of Behçet’s disease.

Panuveitis and retinal vasculitis (Fig. 2) were the most frequently reported eye lesions.15–18 Diffuse vitritis is a constant feature of the posterior segment involvement, and spontaneous resolution is an important diagnostic feature.14 In our study we reported vitritis in 55.6%, anterior uveitis in 50%, and retinal vasculitis in 50%. Periphlebitis, a hallmark of Behçet’s vasculitis may be both leaky and occlusive, retinal arterioles and capillaries are also involved, Occlusion of retinal veins may occur at any location from the central retinal vein to the tiny small branches.13 In this study we reported retinal vein occlusion in 16.7% of patients.

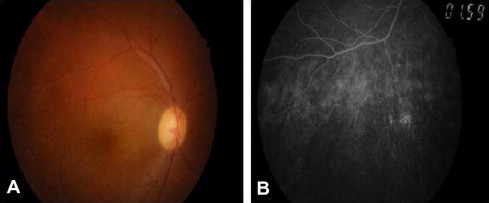

Figure 2.

(A) Colored fundus photograph showing grade 1 vitritis (clear disk and vessels but retinal fiber layer obscured) with retinal vasculitis involving superior temporal branch of retinal vein; (B) shows avascular peripheral retina with perivascular leakage 2ry to peripheral retinal vasculitis in patient with behcet disease.

Neovascularization of the disc (NVD) or elsewhere (NVE) may develop as a complication of retinal vascular occlusion or retinal ischemia induced by uncontrolled intraocular inflammation. It was proven that retinal ischemia is responsible for 13% of eyes with NVD associated with Behçet’s uveitis.19 In this study only one patient (5.6%) had NVEs.

Optic neuropathy is a rare ocular involvement in Behçet’s disease,20 it can be related to an inflammatory neuropathy, a stasis Papilloedema complicating a benign intracranial hypertension or an ischemic neuropathy, a case of simultaneous bilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) with Behçet’s disease was reported in one study.21 In the current study one patient had bilateral papillitis and right 6th nerve palsy. The same finding was reported in a case of Behcet’s disease with acute neuro papillitis and 6th nerve palsy.22

Posterior segment involvement is the most serious ocular complication of Behçet’s disease, leading to blindness with recurrent attacks.23 Macular edema is the most common complication which can evolve into cystoid degeneration and occasionally macular hole.24 The development of partial or full-thickness macular hole, though rarely reported, may cause serious vision loss.25 In the current study, macular edema was reported in (33.3%) and macular hole (5.6%) with significant vision loss was also noticed.

As reported8,15,18 the most common complications of Behçet’s uveitis are cataract, posterior synechiae, macular edema (Fig. 3), optic atrophy, and glaucoma. In the current study beside macular edema 33.3%, cataract 44.4%% posterior synechiae and optic atrophy 11.11% for each and glaucoma 5.6% were found.

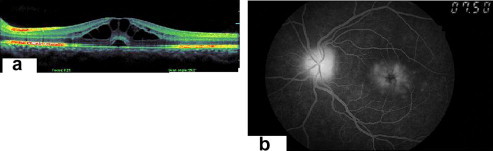

Figure 3.

OCT of the left eye (a) shows cystoid macular edema involving the outer plexiform and inner nuclear layers of the sensory retina with small sensory retinal detachment 2ry to viritis. FFA of the same eye (b) shows typical pattaloid appearance of cystoid macular edema with disk hyperfloresence due to associated papillitis.

Despite modern treatment and intervention strategies, the disease still carries a poor visual prognosis with one-quarter of the patients being blind.26 The disease is more severe and the risk of losing useful vision is higher in males than in females.14 In a Turkish study, it was reported that the estimated risk of losing useful vision after 10 years was 30% in males and 17% in females.14 In contrast, study on Behçet’s disease in Korea revealed that females have a higher frequency of ocular lesions than males.27 In the current study, though the prevalence of male was higher, a significant vision loss was higher in females, where 3 out of 6 females had visual acuity of 0.1 and less. Meanwhile, 7 out of the 12 males had visual acuity of 0.8 and higher.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Saudi Ophthalmological Society, King Saud University.

References

- 1.Behcet H. Über rezidivierende aphthose durch ein Virus verursachte Geschwure am Mund, am Auga und an den Genitalien. Dermatol Wochenschr. 1973;105:1152–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obenauf C.D., Shaw H.E., Sydnor C.F., Sydnor C.F., Klintworth G.K. Sarcoidosis and its ophthalmioc manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86:648–655. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(78)90184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohara K., Okubo A., Sasaki H. Intraocular manifestations of systemic sarcoidosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1992;36:452–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohno S., Ohguchi M., Hirosa S., Matsuda S., Wakisaka A., Aizawa M. Close association of HLA Bw51 with Behcet’s disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:1455–1458. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040433013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones N.P. Sarcoidosis and uveitis. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15:319–326. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(02)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evereklioglu C. Current concepts in the etiology and treatment of Behçet disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:297–350. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yazici H., Fresko I., Yurdakul S. Behçet’s syndrome: disease manifestations, management, and advances in treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:148–155. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang P., Fang W., Meng Q., Ren Y., Xing L., Kijlstra A. Clinical features of Chinese patients with Behçet’s disease. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davatchi F., Shahram F., Chams-Davatchi C., Shams H., Nadji A., Akhlaghi M. Behcet’s disease, from East to West. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:823–833. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benamour S., Chaoui L., Zeroual B., Rafik M., Bettal S., ElKabli H. Study of 673 cases of Behcet’s Disease (BD) In: Bang D., Lee E., Lee S., editors. Behcet’s disease. Design Mecca Publishing; Seoul: 2000. p. 883. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ausaylah Burgan M.D., Mbarak Al-Twal M.D., Jane Kawar M.D. Behcet’s disease: an assessment of cutaneous ocular and articular characteristics in the South of Jordan. J R Med Serv. 2008;15:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease Evaluation of diagnostic (‘classification’) criteria in Behçet’s disease-towards internationally agreed criteria. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31:299–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tugal-Tulkun I. Behcet’s uveitis. Middle East. Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16:219–224. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.58425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tugal-Tutkun I., Onal S., Altan-Yaycioglu R., Altunbas H.H., Urgancioglu M. Uveitis in Behnet disease: an analysis of 880 patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davatchi F., Shahram F., Chams C., Chams H., Nadji A. Bahcet Disease. Acta Med Iran. 2005;43(4) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deuter C.M., Kötter I., Wallace G.R., Murray P.I., Stübiger N., Zierhut M. Behçet’s disease: ocular effects and treatment. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:111–136. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saadoun D., Cassoux N., Wechsler B., Boutin D., Terrada C., Lehoang P. Ocular manifestations of Behcet disease. Rev Med Int. 2010;31:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khairallah M., Attia S., Yahia S.B., Jenzeri S., Ghrissi R., Jelliti B. Pattern of uveitis in Behçet’s disease in a referral center in Tunisia, North Africa. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:135–141. doi: 10.1007/s10792-008-9203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tugal-Tutkun I., Onal S., Altan-Yaycioglu R., Kir N., Urgancioglu M. Neovascularization of the optic disc in Behηet’s disease. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2006;50:256–265. doi: 10.1007/s10384-005-0307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frigui M., Kechaou M., Jemal M., Ben Zina Z., Feki J., Bahloul Z. Optic neuropathy in Behçet’s disease: a series of 18 patients. Rev Med Int. 2009;30:486–491. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamauchi Y., Cruz J.M., Kaplan H.J., Goto H., Sakai J., Usui M. Suspected simultaneous bilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in a patient with Behçet’s disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13:317–325. doi: 10.1080/09273940590950945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozdal P.C., Ortaç S., Taşkintuna I., Firat E. Posterior segment involvement in ocular Behçet’s disease. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2002;12:424–431. doi: 10.1177/112067210201200514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallinaro C., Robinet-Combes A., Sale Y., Richard P., Saraux A. Colin J Neuropapillitis in Behçet disease. A case. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1995;18:147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benchekroun O., Lahbil D., Lamari H., Rachid R., El Belhadji M., Laouissi N. Macular damage in Behçet’s disease. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2004;27:154–159. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(04)96110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheu S.J., Yang C.A. Macular hole in Behcet’s disease. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2004;20:558–562. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70258-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitaichi N., Miyazaki A., Iwata D., Ohno S., Stanford M.R., Chams H. Ocular features of Behcet’s disease: an international collaborative study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1579–1582. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.123554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bang D., Lee J.H., Lee E.S., Lee S., Choi J.S., Kim Y.k., Kwon K.S. Epidemiologic and clinical survey of Behcet’s disease in Korea: the first multicenter study. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:615–618. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]