Abstract

Objective

We conducted a retrospective study examining the outcomes of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to identify parameters associated with prognosis.

Methods

From January 2001 to June 2008, we treated 32 ICH patients (21 men, 11 women; mean age, 62 years) with CKD. We surveyed patients age, sex, underlying disease, neurological status using Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), ICH volume, hematoma location, accompanying intraventricular hemorrhage, anti-platelet agents, initial and 3rd day systolic blood pressure (SBP), clinical outcome using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and complications. The severity of renal functions was categorized using a modified glomerular filtration rate (mGFR). Multifactorial effects were identified by regression analysis.

Results

The mean GCS score on admission was 9.4±4.4 and the mean mRS was 4.3±1.8. The overall clinical outcomes showed a significant relationship on initial neurological status, hematoma volume, and mGFR. Also, the outcomes of patients with a severe renal dysfunction were significantly different from those with mild/moderate renal dysfunction (p<0.05). Particularly, initial hematoma volume and sBP on the 3rd day after ICH onset were related with mortality (p<0.05). However, the other factors showed no correlation with clinical outcome.

Conclusion

Neurological outcome was based on initial neurological status, renal function and the volume of the hematoma. In addition, hematoma volume and uncontrolled blood pressure were significantly related to mortality. Hence, the severity of renal function, initial neurological status, hematoma volume, and uncontrolled blood pressure emerged as significant prognostic factors in ICH patients with CKD.

Keywords: Intracerebral hemorrhage, Chronic kidney disease, Renal failure, Modified Rankin Scale, Prognosis, Mortality

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined as the presence of kidney damage, or a decreased level of kidney function, for longer than 3 months5,13). CKD is known to be associated with an increased risk of bleeding following coronary intervention and the use of anticoagulants1,12,14,21). The high risk of bleeding in CKD patients can be partially attributed to disturbances in the coagulation system, coupled with an altered response to medications8). Therefore, it could be identified as a significant risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality after stroke11).

The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage has been reported to range from 10 to 30 cases per 100000 individuals10). Recently, the incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) with hypertension has been increased in accordance with increased life expectancy due to medical advancements and thus comprehensive treatment strategies are required to treat underlying diseases. In addition, the number of patients who are managing CKD disease and also suffer from ICH has been increasing. The prognosis for ICH concurrent with CKD is poor, and mortality has ranged from 50% to 90%7,17). However, there are few reports discussing prognostic factors that affect the neurological outcome of ICH in patients with CKD.

We retrospectively studied 32 ICH patients who had suffered from CKD to identify factors affecting prognosis in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population

A total of 892 patients with ICH were admitted to our institute between January 2001 and June 2008. Out of them, 32 patients (3.6%, 21 males and 11 females) had been previously treated for CKD. The mean age was 62 years with range between 32-89 years. All 32 patients had been initially diagnosed as spontaneous ICH located in the basal ganglia, thalamus, the cortex, brainstem, and cerebellum by computed tomography (CT). The patients with traumatic ICH, aneurysmal ruptured or arterio-venous malformation were excluded.

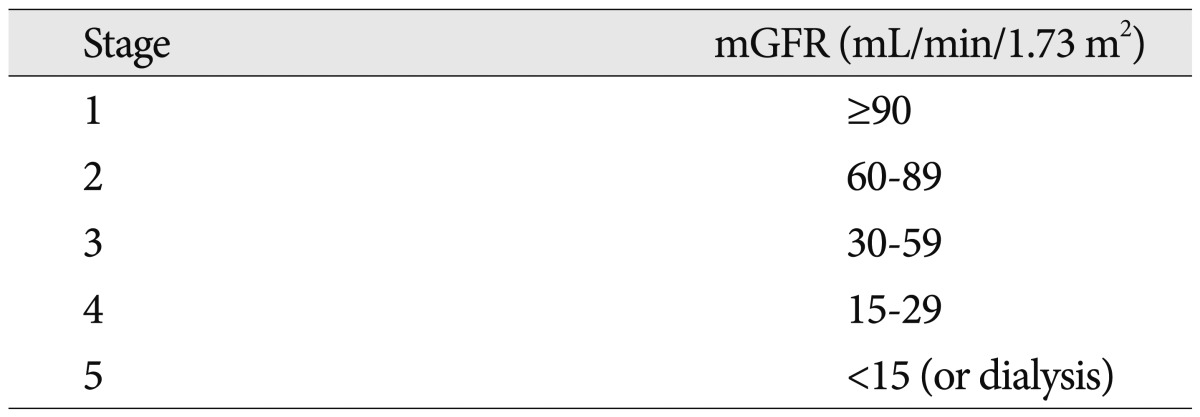

The common causes of CKD are hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and glomerulonephritis. Out of 32 patients, 18 patients had been hospitalized due to hypertensive renal failure, 9 patients due to diabetic nephropathy, 1 patient due to glomerulonephritis, 1 patient due to polycystic kidney disease, and 3 patients due to an asymptomatic urinary abnormality. The severity of CKD was categorized using a modified glomerular filtration rate (mGFR; mL/min/1.73 m2) as follows3) : stage 1 was defined as >90 mL/min/1.73 m2; stage 2 as 60-89 mL/min/1.73 m2; stage 3 as 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m2; stage 4 as 15-29 mL/min/1.73 m2; stage 5 as <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Table 1). A mild grade of renal dysfunction was defined as stage 1, a moderate grade as stage 2, 3 and stage 4, and a severe grade as stage 5. The patients were divided into 2 groups (mild/moderate and severe grade) according to mGFR level.

Table 1.

Relationship between stage of CKD and mGFR

CKD : chronic kidney disease, mGFR : modified glomerular filtration rate

Management of patients

Following diagnosis of ICH, intravenous antihypertensive treatment with nicardipine was immediately initiated to maintain systolic blood pressure (SBP) at <160 mm Hg. Osmotic diuretics such as mannitol were administered following consultation with a nephrologist to reduce cerebral edema. Most patients were managed using conservative treatment without surgical intervention. However, surgery was performed in 6 patients because the patients' neurological status rapidly diminished over time. Of these 6 patients, 2 patients were taken to surgery upon admission, 4 patients underwent surgery during hospitalization for the treatment of ICH, and 1 patient had an additional surgical operation after stereotactic hematoma aspiration because of ICH rebleeding. According to surgical techniques, 2 cases involved open craniotomy for removal of a hematoma and 5 cases received stereotactic aspiration and drainage.

Imaging analysis

The hematoma volumes on admission and at the time of rebleeding were measured using CT. The hematoma volumes were calculated using CT scans (Aquilion ONE™ dynamic volume CT, Toshiba Medical Systems corporation, Japan), assuming an ellipsoid shape and using the formula [(π×width×depth×height)/6].

Analysis of factors affecting clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes using a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) were evaluated at the last follow-up. The predisposing factors in ICH patient with CKD were analyzed to examine the relationships between clinical outcome and the following factors : patient age, sex, hospital days, hematoma volume on admission, hematoma location, modified glomerular filtration rate (mGFR), underlying disease, pro-thrombin time, use of anti-platelet agents, accompanying intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), hemoglobin level, diastolic blood pressure, and sBP on admission and 3 days after ICH development.

Statistical analysis

Relationships between variables and outcomes were examined using univariate analysis (Mann-Whitney U-test). The chi-square test, independent 2-sample t-test, and logistic regression analysis were used depending on characteristics of the variables being compared. Data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation. Analyses were conducted using SPSS ver. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set as p<0.05.

RESULTS

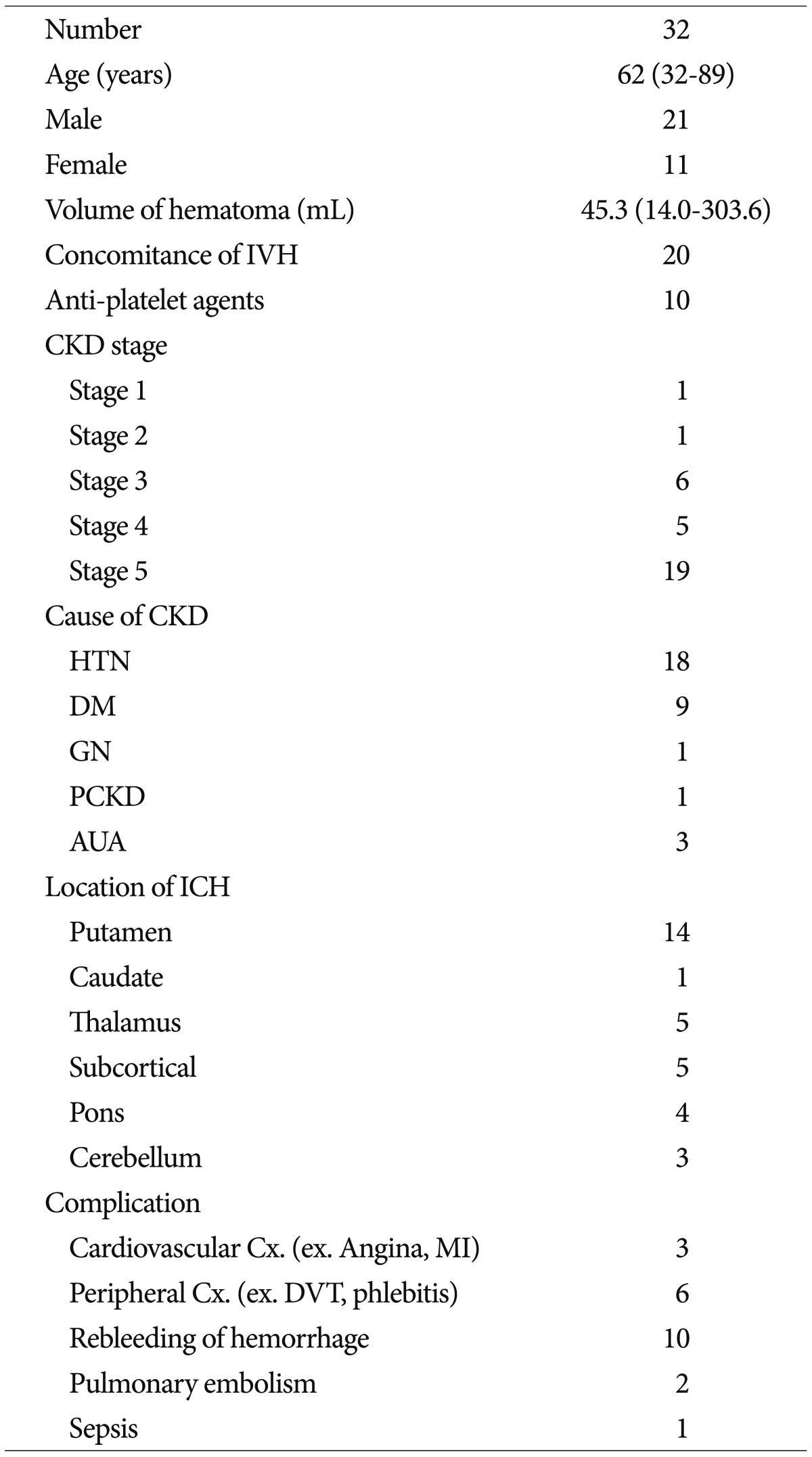

Clinical characteristics of the 32 ICH patients with chronic kidney disease (Table 2). Out of 32 patients, 13 patients had a mild/moderate grade of renal dysfunction and 19 patients needed renal replacement therapy because their renal functions had scored into the severe grade, stage 5 (mGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2). Out of them, 17 patients (89.5%) were managed with hemodialysis and the others were managed with peritoneal dialysis due to the aggravation of renal functions.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients

CKD : chronic kidney disease, HTN : hypertension, DM : diabetes mellitus, GN : glomerulonephritis, PCKD : polycystic kidney disease, AUA : asymptomatic urinary abnormality, IVH : intra-ventricular hemorrhage, ICH : intracerebral hemorrhage, Cx. : complication, MI : myocardial infarction, DVT : deep vein thrombosis

The mean Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) on admission was 9.4±4.4. The mean mRS was 4.3±1.8. The mean hematoma volume was 45.3 mL (range, 14.0-303.6 mL). The mean follow-up time was 42 days (range, 2-268 days). 7 of 32 patients had favorable outcomes (good recovery or moderate disability) and 25 patients showed unfavorable outcomes (poor recovery and death). A total of 11 (34.4%) of the 32 patients died within 19 days (range, 1-87 days). The demise of 3 patients was directly attributable to cerebral hemorrhage and swelling, and 8 cases were caused by sepsis and respiratory failure.

Neurological status on admission, hematoma volume, renal function and clinical outcome

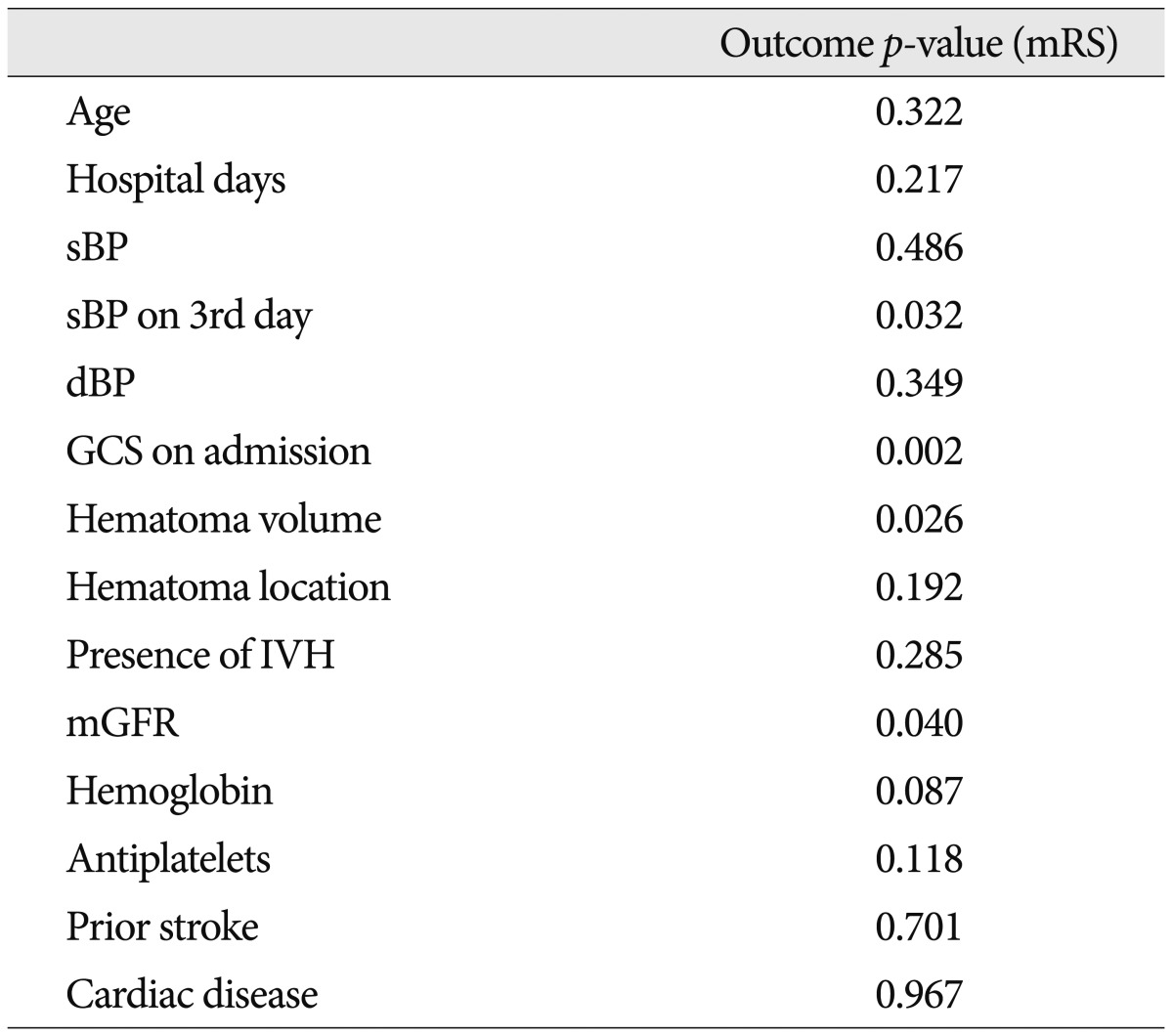

Regression analysis showed that initial neurological status (GCS), hematoma volume, the severity of renal dysfunction defined as mGFR, and 3rd day SBP after ICH development were significantly related to clinical outcome (p<0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Regression analysis of prognostic factors in neurological outcome

mRS : modified Rankin Scale, SBP : systolic blood pressure, dBP : diastolic blood pressure, GCS : Glasgow Coma Scale, IVH : intra-ventricular hemorrhage, mGFR : modified glomerular filtration rate

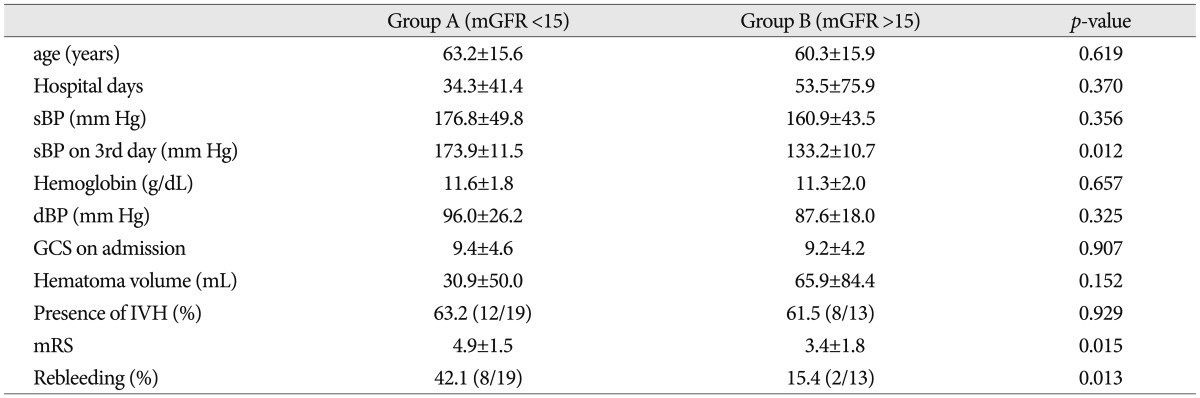

Neurological outcome according to the severity of renal function

The mean mRS scores were 4.9±1.5 in group A (severe stage, mGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2) and 3.4±1.8 in group B (mild/moderate stage, mGFR >15 mL/min/1.73 m2). We found that there were statistically different clinical outcomes between the two groups according to the severity of renal function defined as mGFR. Also, there were significant differences in SBP on 3rd day and rebleeding between the two groups (p<0.05) (Table 4). However, initial GCS scores, hematoma volumes, SBP, IVH presence, and hemoglobin levels were not significantly different between the severe renal dysfunction and mild/moderate renal dysfunction groups. That is, the patients with severe renal dysfunction experienced a worse clinical outcome than those with mild/moderate renal function because of trouble controlling their blood pressure, which led to rebleeding of the hematoma, which resulted in poor clinical outcome.

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics and neurological outcome according to severity of renal function

Values are means±SD for continuous variables, percentages for categorical variables. SBP : systolic blood pressure, dBP : diastolic blood pressure, GCS : Glasgow Coma Scale, IVH : intra-ventricular hemorrhage, mGFR : modified glomerular filtration rate, mRS : modified Rankin Scale

The relationship of hematoma volume, renal function, and systolic blood pressure on 3rd day and relation to unfavorable outcome

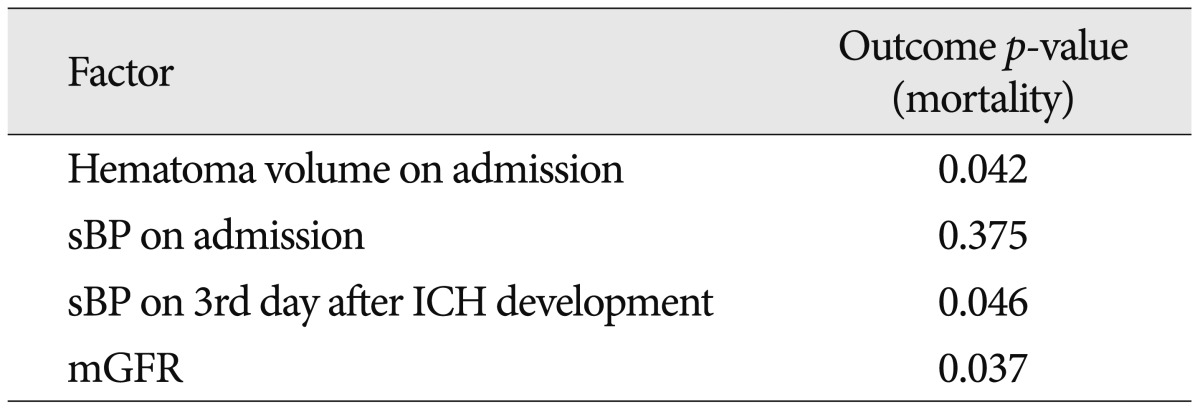

We found that the hematoma volume, renal function, and SBP on the 3rd day were significantly related to unfavorable outcome including mortality (p<0.05) (Table 5). However, initial SBP was not related.

Table 5.

Factors that affect the unfavorable outcome of patients

SBP : systolic blood pressure, ICH : intracerebral hemorrhage, mGFR : modified glomerular filtration rate

Effects of other variables on clinical outcome

Regression analysis showed that clinical outcomes were not related to patient age, gender, hospitalization days, hematoma location, concomitant IVH, use of anti-platelet agents, and SBP or diastolic blood pressure on admission (Table 3).

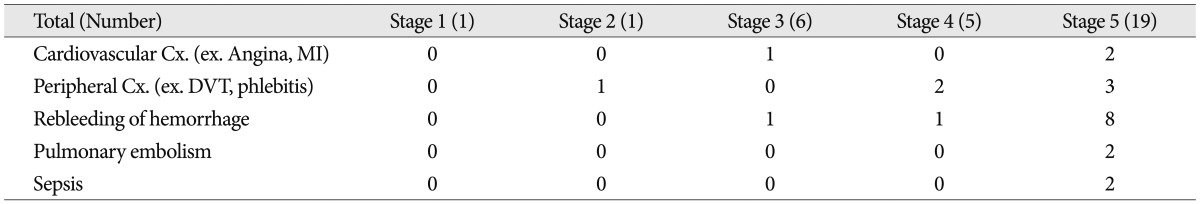

The most common complications were a recurrence of hemorrhage and peripheral complications such as deep vein thrombosis and phlebitis. An inter-group analysis showed no significant relationship between CKD stage and the incidence of complications. However, the comparison did show the tendency for the incidence of complications to increase in patients with higher degrees of renal dysfunction (Table 6).

Table 6.

Complications of ICH in patients with CKD

ICH : intracerebral hemorrhage, CKD : chronic kidney disease, Cx. : complication, MI : myocardial infarction, DVT : deep vein thrombosis

DISCUSSION

The prognosis for ICH patients with CKD is dismal and overall mortality rates have been reported to range from 43.8% to 83%7,9,17,19). In accordance with previous studies, the present study showed an overall mortality rate of 34.4%, which is better than rates reported in other studies. Ochiai et al.18) reported that all patients with a pontine hematoma exhibited deterioration of neurological symptoms, which was later related to mortality during hemodialysis. Our retrospective study had a smaller number of chronic renal disease patients with a pontine hemorrhage than other studies. We think that one of the reasons which our study had a better outcome was, in part, due to the smaller sample size. Another reason is that the mean volume of hematomas in our study was 45.3 mL, which was smaller than the 55.3-109.0 mL volumes reported in other studies16,17).

Some authors reported the relationship between hematoma volume and clinical outcomes in acute ICH patients with CKD16,17). Molshatzki et al.16) concluded the presence of severe CKD in ICH patients was associated with the presence of larger lobar hematomas and a poor outcome. Based on our regression analysis, hematoma volume was significantly related to neurological outcome; however, there was no difference in hematoma volumes among the various renal dysfunction groups.

Previous studies have been examined the association between baseline estimated glomerular filtration rates (GFRs) and clinical outcomes in acute stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) patients11,22). Yahalom et al. reported that chronic renal dysfunction classified by GFR was a strong independent predictor of mortality and poor outcome in patients with acute stroke. However, estimations of the CKD and GFR cutoff points associated with a poor outcome depend on the equation used to estimate GFR. Similarly, our study showed a significant difference in mortality rates and outcomes between patients with different stages of CKD. In our study, patients were divided into 2 groups (mild/moderate and severe renal dysfunction) based on their glomerular filtration rate, because the number of patients with mild renal dysfunction was too small to analyze. We found there was significant difference in clinical outcome between the 2 groups. The majority of patients who succumbed had stage 5 CKD, i.e., mGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 requiring hemo- or peritoneal dialysis; these conditions define end stage renal disease.

CKD patients require careful management because they have a higher risk of bleeding due to disturbances in the coagulation system and altered responses to medications8). In particular, the amounts of osmotic diuretics prescribed to control cerebral edema should be reduced in patients with chronic renal disease. In these patients, it was considered too difficult to strictly control blood pressure and brain swelling, which is associated with a greater risk for vascular complications15). Consequently, patients with intracerebral hemorrhage often experience poor outcomes.

There have been some reports regarding other prognostic factors affecting the clinical outcome of ICH in patients with CKD16,22). Depending on the ICH site, anticoagulants given during dialysis may exacerbate hemorrhaging and increase the risk of cerebral herniation23). Some authors have suggested that systolic blood pressure in ICH patients with CKD is related to prognosis and hematoma enlargement20). But, in our study, initial systolic and diastolic blood pressures were not found to be associated with clinical outcome, although it is often presumed that initial blood pressure readings and strict blood pressure control are required in patients with renal disease to prevent disease progression and expansion of ICH volume20). The 3rd day SBP affected the neurological outcome, and shows the importance of controlling blood pressure during hospitalization rather than the initial blood pressure upon admission, which could mask increased intracranial pressure signs because of ICH development.

Some authors reported that the prognostic factors including GCS score, age (≥80), infratentorial origin of ICH, ICH volume, and presence of intraventricular hemorrhage are related with neurological outcome in ICH patients2,6). Among these factors, Cho et al.4) emphasized that initial neurological status described as GCS and hematoma volume were potentially prognostic factors in putaminal and thalamic ICH. Based on our results, initial GCS score, hematoma volume, severe renal impairment and 3rd day SBP are related with neurological outcome in ICH patients with CKD. In the present study, however, patient age, gender, days of hospitalization, underlying renal disease, hematoma location, concomitant IVH, and use of anti-platelet agents, were not significantly correlated with outcome.

The use of surgical methods to treat ICH remains controversial, particularly for chronic renal disease patients. Open craniotomies and removal of hematomas were avoided whenever possible. Free hand aspiration and stereotactic aspiration of a hematoma are beneficial because platelet dysfunction due to uremia and coagulopathy caused by systemic anticoagulation therapy may result in difficulty in maintaining hemostasis and an increased risk of additional complications after surgery. In the present study, 2 patients underwent a craniotomy for aggressive evacuation of a hematoma, and 5 patients underwent stereotactic aspiration of a hematoma and periventricular hemorrhage. One patient who underwent a craniotomy and 2 patients who underwent free hand or stereotactic aspiration died. Among the patients with a favorable outcome, none of them underwent surgery, and their mean ICH volume was 71.6 mL; whereas the mean ICH volume for patients who died or had unfavorable outcomes was 37.8 mL. It is probable that patients with a favorable neurological status will benefit from conservative treatment even if their hematoma volume is large, whereas patients with an unfavorable neurological status on admission will have an unfavorable outcome irrespective of the surgical procedure. The initial neurological status strongly affected neurological outcome in ICH patients with CKD. Also, patients who had severe renal dysfunction showed unfavorable clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, it is especially difficult to control blood pressure in patients with severe renal impairment. It is possible that poorly controlled blood pressure could increase the chance of rebleeding and worsen the neurological outcomes in these patients. Consequently, low GCS score, small hematoma volume, favorable renal function and sBP control are important to improve the neurological outcome in ICH patients with CKD.

Limitations of the present study include its retrospective design and small sample size. Also, the series of blood pressure readings that were collected from patients were not treated as an independent variable. Additional extended and comprehensive studies may be needed to establish prognostic factors of mortality and clinical outcomes for ICH patients with CKD.

CONCLUSION

We found that impaired renal function was associated with a poor outcome, and was a strong independent predictor of mortality, as well as a high hematoma volume, low GCS score, and uncontrolled blood pressure. In addition, our study showed that patients with severe chronic kidney dysfunction had a higher rate of complications than patients with mild or moderate renal dysfunction. Hence, the severity of renal function, initial neurological status, hematoma volume, and uncontrolled blood pressure emerged as significant prognostic factors in ICH patients with CKD.

References

- 1.Attallah N, Yassine L, Fisher K, Yee J. Risk of bleeding and restenosis among chronic kidney disease patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Nephrol. 2005;64:412–418. doi: 10.5414/cnp64412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briasoulis A, Bakris GL. Chronic kidney disease as a coronary artery disease risk equivalent. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2013;15:340. doi: 10.1007/s11886-012-0340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brosius FC, 3rd, Hostetter TH, Kelepouris E, Mitsnefes MM, Moe SM, Moore MA, et al. Detection of chronic kidney disease in patients with or at increased risk of cardiovascular disease : a science advisory from the American Heart Association Kidney And Cardiovascular Disease Council; the Councils on High Blood Pressure Research, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Epidemiology and Prevention; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group : developed in collaboration with the National Kidney Foundation. Circulation. 2006;114:1083–1087. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho DY, Chen CC, Lee HC, Lee WY, Lin HL. Glasgow Coma Scale and hematoma volume as criteria for treatment of putaminal and thalamic intracerebral hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 2008;70:628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population : Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1–12. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score : a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891–897. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iseki K, Fukiyama K The Okinawa Dialysis Study (OKIDS) Group. Clinical demographics and long-term prognosis after stroke in patients on chronic haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1808–1813. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.11.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jalal DI, Chonchol M, Targher G. Disorders of hemostasis associated with chronic kidney disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36:34–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawamura M, Fijimoto S, Hisanaga S, Yamamoto Y, Eto T. Incidence, outcome, and risk factors of cerebrovascular events in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:991–996. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9631844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleindorfer D, Broderick J, Khoury J, Flaherty M, Woo D, Alwell K, et al. The unchanging incidence and case-fatality of stroke in the 1990s : a population-based study. Stroke. 2006;37:2473–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000242766.65550.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna PR, Naresh S, Krishna GS, Lakshmi AY, Vengamma B, Kumar VS. Stroke in chronic kidney disease. Indian J Nephrol. 2009;19:5–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.50672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Latif F, Kleiman NS, Cohen DJ, Pencina MJ, Yen CH, Cutlip DE, et al. In-hospital and 1-year outcomes among percutaneous coronary intervention patients with chronic kidney disease in the era of drug-eluting stents : a report from the EVENT (Evaluation of Drug Eluting Stents and Ischemic Events) registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease : evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137–147. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim W, Dentali F, Eikelboom JW, Crowther MA. Meta-analysis : low-molecular-weight heparin and bleeding in patients with severe renal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:673–684. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-9-200605020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizobuchi M, Towler D, Slatopolsky E. Vascular calcification : the killer of patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1453–1464. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molshatzki N, Orion D, Tsabari R, Schwammenthal Y, Merzeliak O, Toashi M, et al. Chronic kidney disease in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage : association with large hematoma volume and poor outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31:271–277. doi: 10.1159/000322155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami M, Hamasaki T, Kimura S, Maruyama D, Kakita K. Clinical features and management of intracranial hemorrhage in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis therapy. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2004;44:225–232. doi: 10.2176/nmc.44.225. discussion 233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochiai H, Uezono S, Kawano H, Ikeda N, Kodama K, Akiyama H. Factors affecting outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 2010;32:923–927. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.502279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onoyama K, Kumagai H, Miishima T, Tsuruda H, Tomooka S, Motomura K, et al. Incidence of strokes and its prognosis in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Jpn Heart J. 1986;27:685–691. doi: 10.1536/ihj.27.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thrift AG, Evans RG, Donnan GA. Hypertension and the risk of intracerebral haemorrhage : special considerations in patients with renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2291–2292. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.10.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkelmayer WC, Levin R, Avorn J. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for bleeding complications after coronary artery bypass surgery. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:84–89. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yahalom G, Schwartz R, Schwammenthal Y, Merzeliak O, Toashi M, Orion D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and clinical outcome in patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1296–1303. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.520882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yorioka N, Oda H, Ogawa T, Taniguchi Y, Kushihata S, Takemasa A, et al. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis is superior to hemodialysis in chronic dialysis patients with cerebral hemorrhage. Nephron. 1994;67:365–366. doi: 10.1159/000187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]