Abstract

Nuclear reprogramming resets differentiated tissue to generate induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. While genomic attributes underlying reacquisition of the embryonic-like state have been delineated, less is known regarding the metabolic dynamics underscoring induction of pluripotency. Metabolomic profiling of fibroblasts vs. iPS cells demonstrated nuclear reprogramming-associated induction of glycolysis, realized through augmented utilization of glucose and accumulation of lactate. Real-time assessment unmasked downregulated mitochondrial reserve capacity and ATP turnover correlating with pluripotent induction. Reduction in oxygen consumption and acceleration of extracellular acidification rates represent high-throughput markers of the transition from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism, characterizing stemness acquisition. The bioenergetic transition was supported by proteome remodeling, whereby 441 proteins were altered between fibroblasts and derived iPS cells. Systems analysis revealed overrepresented canonical pathways and interactome-associated biological processes predicting differential metabolic behavior in response to reprogramming stimuli, including upregulation of glycolysis, purine, arginine, proline, ribonucleoside and ribonucleotide metabolism, and biopolymer and macromolecular catabolism, with concomitant downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation, phosphate metabolism regulation, and precursor biosynthesis processes, prioritizing the impact of energy metabolism within the hierarchy of nuclear reprogramming. Thus, metabolome and metaboproteome remodeling is integral for induction of pluripotency, expanding on the genetic and epigenetic requirements for cell fate manipulation.

Keywords: energy metabolism, iPS cells, glycolysis, mitochondria, network biology, oxidative phosphorylation, proteomics, regenerative medicine, systems biology

Recent advances in the science of nuclear reprogramming have enabled next generation regenerative sources derived from somatic tissues. Transduction with stemness transcription factors is sufficient to direct somatic cells back to a primordial embryonic-like state.1 This process of bioengineered reprogramming yields induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells with the capacity to derive all three germ layers without the requirement of an embryo source. The ability to bioengineer genuine pluripotent stem cells holds significant promise to uncover mechanisms of disease, to diagnostically unravel individual variation in disease susceptibility, and to test novel therapeutic strategies.2-5 As proof of principle, iPS cells have been successfully used as a diagnostic or therapeutic source in a number of life-threatening conditions.6-9

Pluripotent Stringency Criteria for Bioengineered Stem Cells

To ensure acquisition of pluripotent traits in reprogrammed iPS cells, comprehensive criteria have been deployed, including morphology, gene expression, and functional characteristics.10-12 Structurally, bona fide iPS cells resemble embryonic stem (ES) cells and share their unlimited ability to self-renew.10 These bioengineered stem cells have similar, although not identical, gene expression and epigenetic profiles (demethylation of pluripotent gene promoters, presence of bivalent domains in developmental genes, and X chromosome reactivation in cells derived from females) to their embryonic counterparts, and express key pluripotency factors (such as Nanog and Oct4) and specific cell surface markers (mouse SSEA-1).10 Validated iPS cells also meet functional pluripotency tests to ensure they can differentiate into all three embryonic germ layers. In vitro stringency tests include the use of ES cell protocols to differentiate iPS cells into defined lineages; however, due to lack of standardization, this approach in isolation does not necessarily prove pluripotency.13 The highest stringency test for human iPS cells is the in vivo teratoma assay, where a subcutaneous injection of cells into an immunodeficient host allows for multilineage tumor formation, and histological analysis is used to confirm induction of all three germ layers within nascent teratomas. Animal-derived iPS cells must also meet in utero criteria by recapitulating the developmental capacity of ES cells. These tests include the generation of chimeric animals with germline transmission, as well as the ultimate test of tetraploid aggregation for production of live offspring genetically identical to the transplanted iPS cells.13 In situ stringency tests may also be utilized to test for regenerative capacity in various disease models. A proposed minimal set of criteria that iPS cells must fulfill encompass: (1) morphological characteristics, including unlimited self-renewal; (2) expression of key pluripotent genes and downregulation of parental cell lineage specific genes; (3) transgene independence; and (4) functional differentiation validated by the highest stringency test available.10-12 Indeed, it is not practical to assess teratoma formation in a high-throughput manner in every derived cell line. Moreover, for regenerative purposes, the isolation or selection of lines that do not form teratomas may in fact be the preferred source. Therefore identifying high-throughput surrogate markers of functional pluripotency would complement existing criteria of proficient nuclear reprogramming.14

Metabolic Regulation of Cell Fate

In addition to the extensively characterized genetic and epigenetic regulators of nuclear reprogramming, recent studies indicate that modulation of mitochondrial dynamics and energy metabolism may contribute to the induction and maintenance of pluripotency.15-25 In this regard, the metabolome of iPS cells resembles that of ES cells and significantly differs from their somatic source, based upon elevated utilization of glucose and production of glycolytic end products, and downregulation of tricarboxylic acid cycle and cellular respiration metabolites.15,16 In fact, multimodal metabolomic profiling in tandem with functional metabolic approaches revealed a bioenergetic transition from somatic oxidative metabolism to glycolysis during iPS cell derivation.15,16 Moreover, changes in stoichiometry of the mitochondrial electron transport chain occur in the initial stage of nuclear reprogramming, and elevated glycolytic gene expression preceded induction of pluripotent genes, suggesting that a switch in energy metabolism is required to fuel nuclear reprogramming.15,26 This metabolic transition from oxidative metabolism to glycolysis is consistent across species, cell lines, and reprogramming formulations, and somatic sources that display a greater glycolytic and lower oxidative capacity demonstrate higher efficiency of nuclear reprogramming.15-17,27 The energetic conversion can be targeted to control the reprogramming process directly by stimulating glycolysis, either pharmacologically or by increasing glycolytic intermediates, or indirectly through hypoxic stimulation or inhibition of the p53 signaling pathway, increasing pluripotent induction.15,16,28-39 Nuclear reprogramming can be impaired by inhibiting glycolysis or stimulating oxidative metabolism.15,16,39 With growing evidence for remodeling of energy metabolism in cell fate decisions, acquisition of a glycolytic metabotype of stem cells may offer early criteria for establishing functional pluripotency.

Metabolic Blueprint of Pluripotency

Metabolic flux in iPS cells

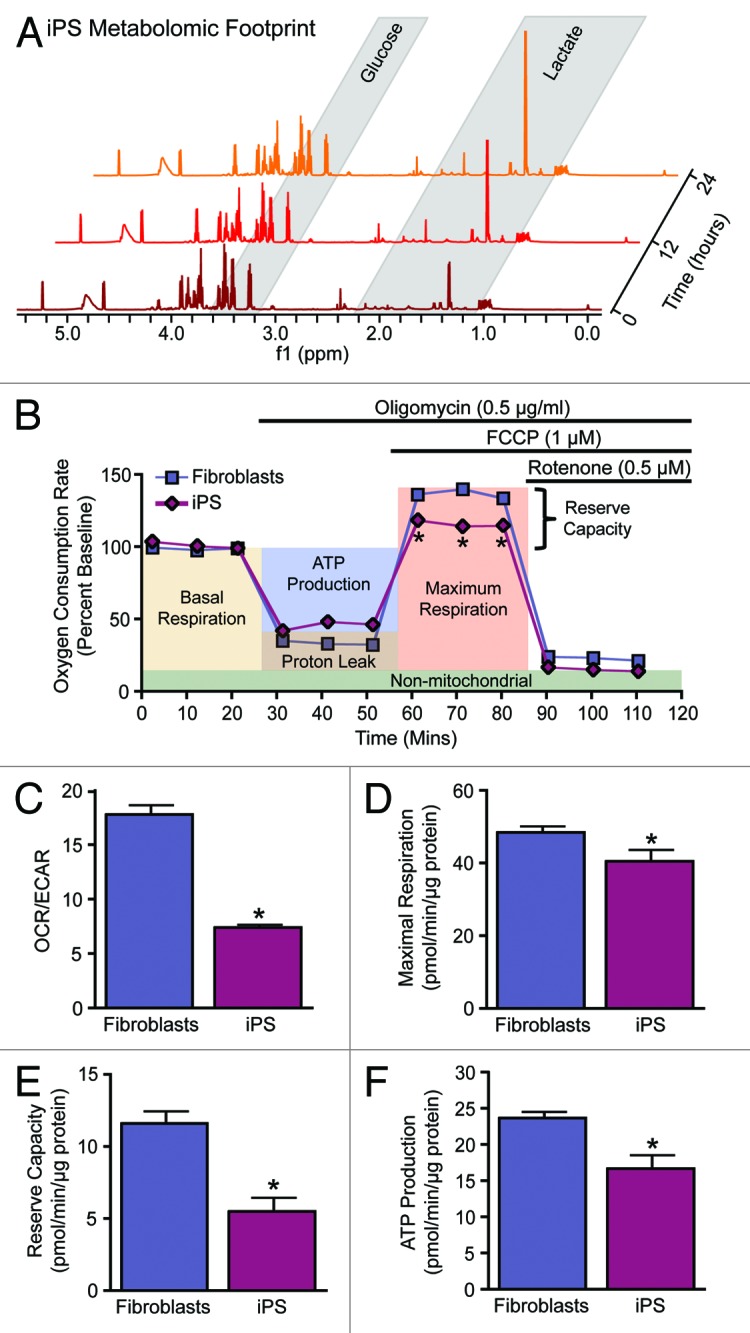

Multimodal bioenergetic characterization of nuclear reprogramming has established remodeling occurring at the level of the metabolome, metabolic infrastructure, and mitochondria.15,16,21,27,40 Pluripotent stem cells benefit from acquiring a glycolytic metabotype associated with a faster rate of ATP generation compared with oxidative metabolism and the production of biosynthetic precursors in conjunction with the pentose phosphate pathway, thus enabling iPS cells to fuel anabolic requirements.40-42 Agents that promote glycolysis expedite the reprogramming process, while stimulation of oxidative metabolism impairs induction of pluripotency.15,39,43,44 Utilization of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS) has enabled unprecedented coverage of small molecular weight compounds or metabolites in biological systems.45-47 Applying such high-throughput technologies to nuclear reprogramming demonstrated that the metabolome of iPS cells segregates away from parental sources and clusters with that of ES cell counterparts, exhibiting a metabolomic extracellular footprint and intracellular fingerprint characteristic of bona fide pluripotent cells.15,16 Monitoring extracellular metabolites in cell culture media by serial NMR measurements established a greater utilization of glucose and greater production of the glycolytic end product lactate in iPS cells compared with their parental source (Fig. 1A). Profiling of the intracellular metabolome supported an iPS cell signature distinct from the parental source and characterized by a reduction in metabolites associated with oxidative metabolism, defining the transition from cellular respiration to glycolysis.15,16 Beyond metabolomic profiling, validated extracellular flux technology established functional monitoring of cellular bioenergetics (Fig. 1B–F). Measurement of the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) enabled real-time assessment of the balance between oxidative metabolism and glycolysis to document nuclear reprogramming-induced metabolic remodeling as indicated by a reduction in the iPS cell OCR/ECAR ratio compared with parental fibroblasts (Fig. 1C). Sequential supplementation of the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin, an electron transport chain uncoupler, carbonyl cyanide 4-[trifluoromethoxy]phenylhydrazone (FCCP), and the complex 1 inhibitor rotenone, dissected key parameters of mitochondrial physiology, including maximal respiration rate, reserve capacity, and ATP production (Fig. 1B). Consistent with bioenergetic remodeling and reduction in energy turnover and total ATP levels,15-18,41,48 iPS cells were found to continuously respire near their maximal rates as indicated by lower maximal respiration (Fig. 1D) and reserve capacity (Fig. 1E), resulting in reduced ATP production (Fig. 1F) compared with the somatic source. Real-time monitoring of cellular bioenergetics thus offers a novel high-throughput platform for assessing functional pluripotency.

Figure 1. Metabolic reprogramming from oxidative metabolism in fibroblasts to glycolysis in iPS cells. Representative serial nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomic footprinting of cell culture media indicates elevated glucose utilization and accumulation of lactate in iPS cells (A). High-throughput simultaneous measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) (B) indicates reduced oxygen utilization and greater reliance on glycolysis in iPS cells (C). Extracellular flux analysis in response to oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone demonstrates an iPS cell specific mitochondrial profile characterized by reduced maximal respiration (D), reserve capacity (E) and ATP turnover (F). Values represent mean ± standard error, n = 8 per group. Significance was determined by Student t test. *P < 0.05 vs. MEF.

Nuclear reprogramming transforms the mitochondrial infrastructure

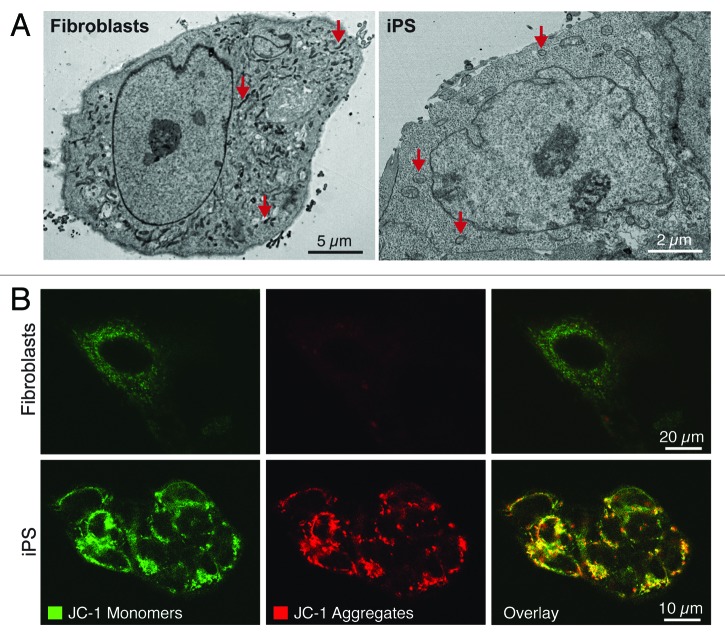

The cell’s central energy generators, the mitochondria, also reliably undergo multilevel reorganization during nuclear reprogramming of fibroblasts, indicating mitochondrial metamorphosis as a conserved feature of pluripotency induction.15,17,18,48,49 Nuclear reprogramming induces a reduction in mitochondrial density compared with the parental source, with remaining mitochondria displaying an immature ultrastructure consisting of spherical structures with undeveloped cristae, similar to those observed in ES cells (Fig. 2A).15,17,18,20,48,49 This is in contrast to the branched tubular shaped mitochondria with electron-dense and well-developed cristae of parental fibroblasts (Fig. 2A). Mitochondrial localization also transitions during nuclear reprogramming from widespread cytoplasmic networks to a perinuclear localization (Fig. 2A), which may reflect reorganization in bioenergetic demands from cytosolic organelles to the nucleus in support of ongoing genetic and epigenetic remodeling.15,17,18,49 As perinuclear localization is a consistent feature of a number of diverse stem cell populations, it may provide an additional criterion for stemness.48,50-52 Like their embryonic counterparts, iPS cells accumulate mitochondrial membrane potential-dependent probes to a greater extent than their parental fibroblasts do (Fig. 2B), which may represent a valuable marker of pluripotent induction.15,20,53 Recent evidence indicates that inhibition of mitochondrial division significantly impairs the ability of fibroblasts to undergo nuclear reprogramming,54 supporting an essential role for mitochondrial plasticity in nuclear reprogramming and maintenance of the pluripotent state.

Figure 2. Nuclear reprogramming induced restructuring of the mitochondrial infrastructure. The mitochondrial anatomy and prevalence is remodeled during nuclear reprogramming as resolved by electron microscopy (arrows demarcate mitochondria) (A). iPS cells demonstrate mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization compared with parental fibroblasts based upon mitochondrial accumulation of JC-1 (B).

Nuclear reprogramming induces remodeling of the metabolic infrastructure

To accommodate the metabolic transition from oxidative metabolism to glycolysis underlying induction of pluripotency, the bioenergetic infrastructure of the cell undergoes extensive remodeling at the level of the transcriptome, proteome, and mitochondria. Glycolysis and oxidative metabolism gene expression changes are consistently observed when examining iPS cells compared with the parental source, revealing a conserved feature underlying nuclear reprogramming dynamics.16,17,19,55 In particular, genes involved in glucose uptake (SLC2A3 encoding GLUT3), glucose phosphorylation (HK3 and GCK), the final steps of glycolysis (PGAM2, ENO, PKLR, and LDH), and the non-oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway (TKT and RPIA) are upregulated, while the intervening steps of glycolysis (GPI, PFK, and ALDO) are downregulated.17,19 This suggests that glycolytic intermediates may be shunted into the pentose phosphate pathway to produce anabolic precursors for biosynthetic pathways and to maintain cellular antioxidant defenses.17,19 Temporal assessment of glycolytic genes during reprogramming revealed the promotion of glycolytic gene expression prior to induction of pluripotent genes, indicating that metabolic remodeling may not be a consequence of reprogramming, but rather required to fuel pluripotency induction.15 Upstream regulators of gene transcription also support metabolic remodeling during reprogramming. The epigenetic methylation status of genes involved in glycolysis and oxidative metabolism of iPS cells is similar to ES cells and differs from their parental source, indicating an additional biomarker of pluripotent metabolic competence.16 Recent evidence has implicated a role for miRNAs in controlling cellular fate,56-58 with miR-302–367 specifically implicated in pluripotent induction and maintenance, potentially by overcoming the metabolic reprogramming barrier and regulating genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial biogenesis.59

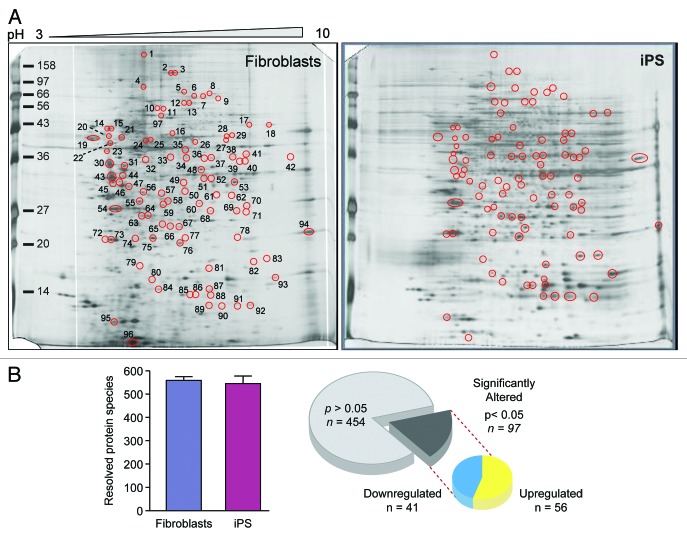

Concomitant with transcriptional remodeling of metabolic genes is the restructuring of the metaboproteome, with targeted analysis revealing that the metabolic infrastructure of iPS cells closely resembles ES cells and differs from their somatic source.15 Specifically, pluripotent cells exhibit predominant upregulation of glycolytic enzymes and changes in stoichiometry of specific mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes.15,26,60 To examine the priority of these changes with respect to global proteomic remodeling associated with nuclear reprogramming, differential proteomic analysis was performed by two-dimensional electrophoresis together with nanoelectrospray tandem MS to detect and assign identities to significantly altered proteins (Fig. 3; Fig. S1 and Tables S1 and S2). A consistent number of protein species were observed in both fibroblast and iPS cell extracts, and within the 97 spots that differed significantly between groups, there were 441 unique proteins identified, 210 exclusively found in upregulated spots, 166 exclusive to downregulated spots, whereas 65 proteins were identified in both upregulated and downregulated spots. Ontological analysis categorized altered proteins across a spectrum of subcellular locations, including the mitochondria (Fig. S1). Transcriptional and proteomic remodeling of the metabolic infrastructure thus underlies the nuclear reprogramming-induced switch from oxidative metabolism to glycolysis; however the prioritization of these changes within the hierarchy of reprogramming remains unknown.

Figure 3. Nuclear reprogramming induced remodeling of the bioenergetic infrastructure. iPS cell-specific proteome is revealed in representative silver-stained, broad pH range (3–10) large format two-dimensional gels (A). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis consistently resolved on the order of 550 protein species in fibroblast and iPS cell extracts, with densitometric quantification identifying a subset of 97 significantly altered protein spots (21% of the total resolved) following nuclear reprogramming, with significance determined by Student t test (P < 0.05) (B).

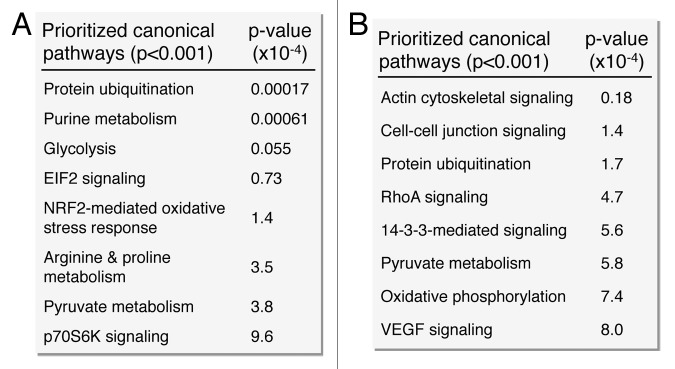

Systems biology prioritizes metabolic protein remodeling

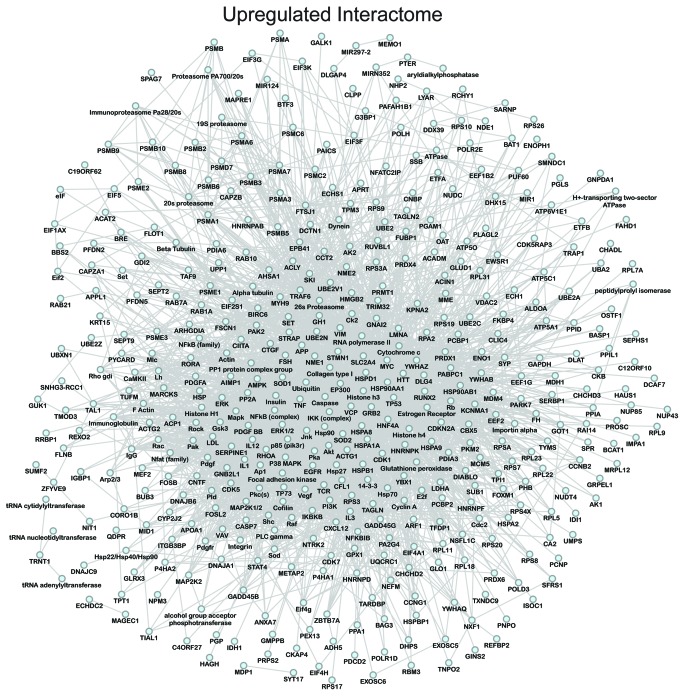

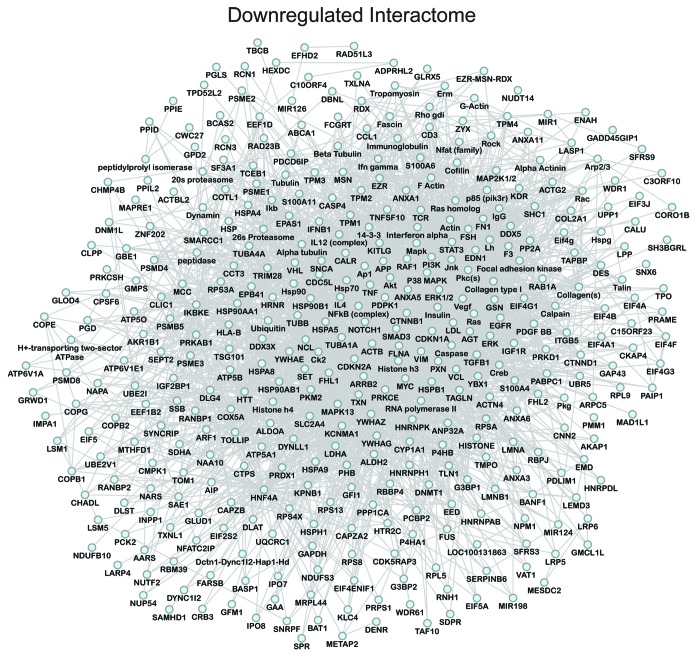

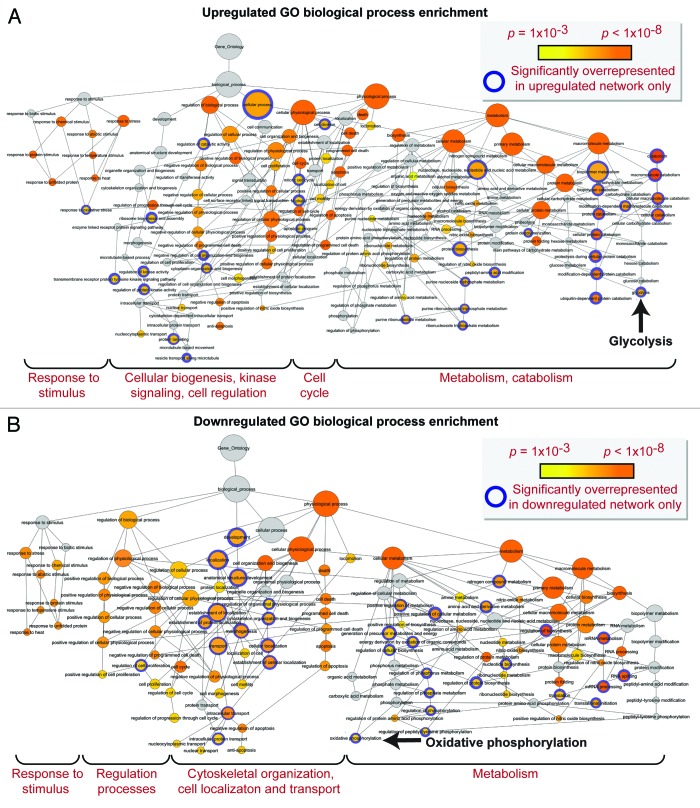

Network analysis was performed to obtain the distinguishing characteristics of upregulated and downregulated subproteomes.61 Ingenuity Pathway Analysis interaction mapping clustered upregulated proteins within a single fully connected 457 node, 3069 edge network (Fig. 4; Fig. S2), while downregulated proteins were encompassed by a separate 392 node, 3237 edge network (Fig. 5; Fig. S2), both exhibiting scale-free topology. Bioinformatic interrogation of the upregulated subproteome extracted 8 overrepresented canonical pathways (Fig. 6A), half of which were metabolic processes: purine metabolism, glycolysis, arginine/proline metabolism, and pyruvate metabolism. Eight canonical pathways were also prioritized from the downregulated subproteome, including pyruvate metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 6B). Network prioritization of gene ontology (GO) biological processes reflected similarities with prioritized canonical pathways and revealed that metabolic functions related mainly to purine metabolism and glycolysis were uniquely represented in the upregulated network (Fig. 7A), while oxidative phosphorylation, phosphate metabolism regulation, precursor biosynthesis processes, and RNA-related metabolic functions were unique to the downregulated network (Fig. 7B). Appearance of glycolysis only in the upregulated network and oxidative phosphorylation only in the downregulated counterpart (demarcated by arrows in Fig. 7A and B) is consistent with observed functional bioenergetic differences between somatic and iPS cells. Proteomic deconvolution combined with in silico network generation and interrogation of proteome-associated canonical pathways and network-associated biological processes thus provides a systems-based assessment of the metabolic reprogramming associated with pluripotent induction.

Figure 4. Pathway analysis interaction mapping clustered the upregulated subproteome into a fully connected network of 457 nodes and 3069 edges. Network degree distribution exhibits scale-free topology as defined by the relationship between node degree (k) vs. node degree distribution (P[k]), the proportion of all nodes at each specified degree (see Fig. S2A).68,69

Figure 5. Pathway analysis interaction mapping clustered the downregulated subproteome into a fully connected network of 392 nodes and 3237 edges. Network degree distribution exhibits scale-free topology as defined by the relationship between node degree (k) vs. node degree distribution (P[k]), the proportion of all nodes at each specified degree (see Fig. S2B).68,69

Figure 6. Pathway analysis interaction mapping prioritizes canonical metabolic processes within the upregulated and downregulated iPS subproteomes. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis identified a number of overrepresented (P < 0.001) metabolic canonical pathways within the upregulated (A) and downregulated proteins arising from somatic cell reprogramming (B).

Figure 7. Gene ontology biological process prioritization within the upregulated and downregulated iPS cell subproteome networks. Unique to the upregulated network were 36 significantly overrepresented (P < 0.001) GO processes, including catabolic/metabolic functions mainly related to purine metabolism and glycolysis, cell cycle functions, and processes related to cell organization/biogenesis, kinase signaling, and an assortment of cell regulation functions (A). Unique to the downregulated network were 34 significantly overrepresented processes, associated with oxidative phosphorylation and several phosphate metabolism regulation and RNA related metabolic functions, as well as cytoskeletal structure/morphology and organization processes, cell localization, and transport (B).

In summary, the metabolic transition from oxidative metabolism to glycolysis is a consistent feature of the nuclear reprogramming process resulting in an ES cell-like metabolome that characterizes generated iPS cells. The present study delineated metabolome and metaboproteome remodeling underlying the nuclear reprogramming of somatic tissue into iPS cells. Indeed, acquiring a glycolytic metabotype may surpass a bioenergetic barrier that cells must achieve to undergo successful reprogramming and establish metabolic competence for regenerative applications. As such, metabolic profiling represents a novel stringency criterion of bioengineered pluripotency.

Materials and Methods

Cell derivation, protein extraction, and quantification

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were obtained from embryos at 14.5 d post coitum. Resulting fibroblasts were plated for 2–3 passages to full confluency. Transduced fibroblasts were cultured in ES cell maintenance medium, consisting of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Millipore) supplemented with pyruvate (Lonza), L-glutamine (Invitrogen), non-essential amino acids (Mediatech), 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 15% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), and LIF (Millipore).15 Transfer vectors were generated with pSIN-SEW based vector, pSIN-CSGWdlNotI, with full-length human OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC cDNAs (Open Biosystems).6 Clonogenic expansion produced reprogrammed cell lines that were maintained in ES cell maintenance medium.

Live cell metabolic analysis

Oxygen consumption rates and extracellular acidification rates were measured using an XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Biosciences). In brief, cells were plated into wells of an XF24 cell culture microplate and maintained overnight to ensure 80% confluence. Prior to assay, plates were equilibrated in unbuffered XF assay medium supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamax, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1× nonessential amino acids, and 1% fetal bovine serum in the absence of CO2 for 1 h.62 Mitochondrial processes were interrogated by serial addition of oligomycin (0.5 μg/ml), FCCP (1 μM), and rotenone (0.5 μM). Each plotted value is the mean of at least 10 replicates and is normalized to baseline oxygen consumption and to total protein quantified using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and protein identification

Fully confluent cultured cells (MEF, iPS; three 10 cm dishes per cell line) were washed extensively with phosphate buffered saline (10 × 10 mL each). Protein was then extracted in situ from adherent cells in 500 μL lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% [w/v] 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate), and quantified in triplicate by Bio-Rad protein assay using the microassay procedure with a bovine γ-globulin standard. As described previously,63,64 protein extracts (100 μg) were resolved in the first dimension by immobilized pH gradients (pH 3–10) and in the second dimension by SDS-PAGE (12.5%) using a Protean® II XL system (Bio-Rad). Two-dimensional gels were silver stained, digitized for spot image analysis and normalized by total spot intensity using Bio-Rad PDQuest v.7.4.0.63,64 Altered protein species were isolated, destained, and prepared for nanoelectrospray linear ion trap tandem MS by reduction, alkylation, tryptic digestion, peptide extraction, and drying.65 Peptides were separated on ProteoPep C18 PicoFrit™ nanoflow column (New Objective) using an Eksigent nanoHPLC system (MDS Sciex) coupled to a hybrid LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Eluted peptide ions were continuously monitored between 375–1600 m/z, with automatic switching to MS/MS collision-induced dissociation mode for ions exceeding an intensity of 8000. Protein identities were assigned by matching multiple peptide spectra to theoretical tryptic fragments in Swiss-Prot (v.53.0) using Mascot™ v.2.2.66

Network derivation and bioinformatic interrogation

Upregulated and downregulated functional networks associated with differentially expressed proteins were identified using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis and Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base (Ingenuity® Systems, http://www.ingenuity.com), as previously described.64 Ingenuity was also used to identify significantly overrepresented canonical pathways associated with the altered proteome. Composite networks, constructed by merging Ingenuity functional subnetworks, were depicted using Cytoscape 2.8.3, with topological properties characterized as an undirected network using Network Analyzer.67 Interrogation of composite networks was performed with the Cytoscape module BiNGO 2.3 (Bioinformatic Network Gene Ontology), to assess gene ontology (GO) biological process enrichment for interpretation of composite network functional interdependencies. Individual categories were considered for overrepresentation by BiNGO and Ingenuity on the basis of hypergeometric distributions, comparing proportional occurrence within the network relative to overall occurrence in the entire proteome.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, comparison between groups was performed using a Student t test of variables with 95% confidence intervals, with data expressed as mean ± standard error. For BiNGO, a hypergeometric distribution with Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate correction was utilized to determine significant overrepresentation of GO biological processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Fondation Leducq, Marriott Foundation, and Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/25509

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/25509

References

- 1.Cherry AB, Daley GQ. Reprogramming cellular identity for regenerative medicine. Cell. 2012;148:1110–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sancho-Martinez I, Li M, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Disease correction the iPSC way: advances in iPSC-based therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:746–9. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson TJ, Terzic A. Induced pluripotent stem cells: an emerging theranostics platform. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:648–50. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue H, Yamanaka S. The use of induced pluripotent stem cells in drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:655–61. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis J, Bhatia M. iPSC technology: platform for drug discovery. Point. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:639–41. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Yamada S, Perez-Terzic C, Ikeda Y, Terzic A. Repair of acute myocardial infarction by human stemness factors induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2009;120:408–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.865154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318:1920–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wernig M, Zhao JP, Pruszak J, Hedlund E, Fu D, Soldner F, et al. Neurons derived from reprogrammed fibroblasts functionally integrate into the fetal brain and improve symptoms of rats with Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5856–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu D, Alipio Z, Fink LM, Adcock DM, Yang J, Ward DC, et al. Phenotypic correction of murine hemophilia A using an iPS cell-based therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:808–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812090106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maherali N, Hochedlinger K. Guidelines and techniques for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis J, Bruneau BG, Keller G, Lemischka IR, Nagy A, Rossant J, et al. Alternative induced pluripotent stem cell characterization criteria for in vitro applications. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:198–9, author reply 202. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daley GQ, Lensch MW, Jaenisch R, Meissner A, Plath K, Yamanaka S. Broader implications of defining standards for the pluripotency of iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:200–1, author reply 202. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Terzic A. Induced pluripotent stem cells: developmental biology to regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:700–10. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith KP, Luong MX, Stein GS. Pluripotency: toward a gold standard for human ES and iPS cells. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:21–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folmes CD, Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Arrell DK, Lindor JZ, Dzeja PP, et al. Somatic oxidative bioenergetics transitions into pluripotency-dependent glycolysis to facilitate nuclear reprogramming. Cell Metab. 2011;14:264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panopoulos AD, Yanes O, Ruiz S, Kida YS, Diep D, Tautenhahn R, et al. The metabolome of induced pluripotent stem cells reveals metabolic changes occurring in somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Res. 2012;22:168–77. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varum S, Rodrigues AS, Moura MB, Momcilovic O, Easley CA, 4th, Ramalho-Santos J, et al. Energy metabolism in human pluripotent stem cells and their differentiated counterparts. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prigione A, Fauler B, Lurz R, Lehrach H, Adjaye J. The senescence-related mitochondrial/oxidative stress pathway is repressed in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:721–33. doi: 10.1002/stem.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prigione A, Lichtner B, Kuhl H, Struys EA, Wamelink M, Lehrach H, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells harbor homoplasmic and heteroplasmic mitochondrial DNA mutations while maintaining human embryonic stem cell-like metabolic reprogramming. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1338–48. doi: 10.1002/stem.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong L, Tilgner K, Saretzki G, Atkinson SP, Stojkovic M, Moreno R, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell lines show stress defense mechanisms and mitochondrial regulation similar to those of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:661–73. doi: 10.1002/stem.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folmes CD, Nelson TJ, Dzeja PP, Terzic A. Energy metabolism plasticity enables stemness programs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1254:82–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folmes CD, Dzeja PP, Nelson TJ, Terzic A. Metabolic plasticity in stem cell homeostasis and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:596–606. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shyh-Chang N, Locasale JW, Lyssiotis CA, Zheng Y, Teo RY, Ratanasirintrawoot S, et al. Influence of threonine metabolism on S-adenosylmethionine and histone methylation. Science. 2013;339:222–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1226603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Nuebel E, Daley GQ, Koehler CM, Teitell MA. Metabolic regulation in pluripotent stem cells during reprogramming and self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:589–95. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Prisco M, Ertel A, Tsirigos A, Lin Z, Pavlides S, et al. Ketones and lactate increase cancer cell “stemness,” driving recurrence, metastasis and poor clinical outcome in breast cancer: achieving personalized medicine via Metabolo-Genomics. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1271–86. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.8.15330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansson J, Rafiee MR, Reiland S, Polo JM, Gehring J, Okawa S, et al. Highly coordinated proteome dynamics during reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1579–92. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panopoulos AD, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Anaerobicizing into pluripotency. Cell Metab. 2011;14:143–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ezashi T, Das P, Roberts RM. Low O2 tensions and the prevention of differentiation of hES cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4783–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501283102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers DE, Millman JR, Huang RB, Colton CK. Effects of oxygen on mouse embryonic stem cell growth, phenotype retention, and cellular energetics. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;101:241–54. doi: 10.1002/bit.21986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westfall SD, Sachdev S, Das P, Hearne LB, Hannink M, Roberts RM, et al. Identification of oxygen-sensitive transcriptional programs in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:869–81. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohyeldin A, Garzón-Muvdi T, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:150–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshida Y, Takahashi K, Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:237–41. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MN, Nakano K, Bartrons R, et al. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banito A, Rashid ST, Acosta JC, Li S, Pereira CF, Geti I, et al. Senescence impairs successful reprogramming to pluripotent stem cells. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2134–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.1811609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong H, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Kanagawa O, Nakagawa M, et al. Suppression of induced pluripotent stem cell generation by the p53-p21 pathway. Nature. 2009;460:1132–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawamura T, Suzuki J, Wang YV, Menendez S, Morera LB, Raya A, et al. Linking the p53 tumour suppressor pathway to somatic cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1140–4. doi: 10.1038/nature08311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, Collado M, Villasante A, Strati K, Ortega S, Cañamero M, et al. The Ink4/Arf locus is a barrier for iPS cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1136–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marión RM, Strati K, Li H, Murga M, Blanco R, Ortega S, et al. A p53-mediated DNA damage response limits reprogramming to ensure iPS cell genomic integrity. Nature. 2009;460:1149–53. doi: 10.1038/nature08287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu S, Li W, Zhou H, Wei W, Ambasudhan R, Lin T, et al. Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:651–5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folmes CD, Nelson TJ, Terzic A. Energy metabolism in nuclear reprogramming. Biomark Med. 2011;5:715–29. doi: 10.2217/bmm.11.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Khvorostov I, Hong JS, Oktay Y, Vergnes L, Nuebel E, et al. UCP2 regulates energy metabolism and differentiation potential of human pluripotent stem cells. EMBO J. 2011;30:4860–73. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shyh-Chang N, Zheng Y, Locasale JW, Cantley LC. Human pluripotent stem cells decouple respiration from energy production. EMBO J. 2011;30:4851–2. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menendez JA, Vellon L, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A. mTOR-regulated senescence and autophagy during reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency: a roadmap from energy metabolism to stem cell renewal and aging. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3658–77. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.21.18128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vazquez-Martin A, Vellon L, Quirós PM, Cufí S, Ruiz de Galarreta E, Oliveras-Ferraros C, et al. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) provides a metabolic barrier to reprogramming somatic cells into stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:974–89. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.5.19450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicholson JK, Lindon JC, Holmes E. ‘Metabonomics’: understanding the metabolic responses of living systems to pathophysiological stimuli via multivariate statistical analysis of biological NMR spectroscopic data. Xenobiotica. 1999;29:1181–9. doi: 10.1080/004982599238047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fiehn O. Metabolomics--the link between genotypes and phenotypes. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48:155–71. doi: 10.1023/A:1013713905833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. Innovation: Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:263–9. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suhr ST, Chang EA, Tjong J, Alcasid N, Perkins GA, Goissis MD, et al. Mitochondrial rejuvenation after induced pluripotency. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeuschner D, Mildner K, Zaehres H, Schöler HR. Induced pluripotent stem cells at nanoscale. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:615–20. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piccoli C, Ria R, Scrima R, Cela O, D’Aprile A, Boffoli D, et al. Characterization of mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial oxygen consuming reactions in human hematopoietic stem cells. Novel evidence of the occurrence of NAD(P)H oxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26467–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen CT, Shih YR, Kuo TK, Lee OK, Wei YH. Coordinated changes of mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant enzymes during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:960–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lonergan T, Bavister B, Brenner C. Mitochondria in stem cells. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:289–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chung S, Dzeja PP, Faustino RS, Perez-Terzic C, Behfar A, Terzic A. Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is required for the cardiac differentiation of stem cells. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(Suppl 1):S60–7. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vazquez-Martin A, Cufi S, Corominas-Faja B, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Vellon L, Menendez JA. Mitochondrial fusion by pharmacological manipulation impedes somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency: new insight into the role of mitophagy in cell stemness. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:393–401. doi: 10.18632/aging.100465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prigione A, Adjaye J. Modulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetic metabolism upon in vitro and in vivo differentiation of human ES and iPS cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:1729–41. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103198ap. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim H, Lee G, Ganat Y, Papapetrou EP, Lipchina I, Socci ND, et al. miR-371-3 expression predicts neural differentiation propensity in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lipchina I, Elkabetz Y, Hafner M, Sheridan R, Mihailovic A, Tuschl T, et al. Genome-wide identification of microRNA targets in human ES cells reveals a role for miR-302 in modulating BMP response. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2173–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.17221311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Subramanyam D, Lamouille S, Judson RL, Liu JY, Bucay N, Derynck R, et al. Multiple targets of miR-302 and miR-372 promote reprogramming of human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:443–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lipchina I, Studer L, Betel D. The expanding role of miR-302-367 in pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:1517–23. doi: 10.4161/cc.19846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vazquez-Martin A, Corominas-Faja B, Cufi S, Vellon L, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez OJ, et al. The mitochondrial H(+)-ATP synthase and the lipogenic switch: new core components of metabolic reprogramming in induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:207–18. doi: 10.4161/cc.23352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arrell DK, Terzic A. Systems proteomics for translational network medicine. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:478. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang J, Nuebel E, Wisidagama DR, Setoguchi K, Hong JS, Van Horn CM, et al. Measuring energy metabolism in cultured cells, including human pluripotent stem cells and differentiated cells. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1068–85. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arrell DK, Niederländer NJ, Faustino RS, Behfar A, Terzic A. Cardioinductive network guiding stem cell differentiation revealed by proteomic cartography of tumor necrosis factor alpha-primed endodermal secretome. Stem Cells. 2008;26:387–400. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zlatkovic-Lindor J, Arrell DK, Yamada S, Nelson TJ, Terzic A. ATP-sensitive K(+) channel-deficient dilated cardiomyopathy proteome remodeled by embryonic stem cell therapy. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1355–67. doi: 10.1002/stem.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Behfar A, Perez-Terzic C, Faustino RS, Arrell DK, Hodgson DM, Yamada S, et al. Cardiopoietic programming of embryonic stem cells for tumor-free heart repair. J Exp Med. 2007;204:405–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Assenov Y, Ramírez F, Schelhorn SE, Lengauer T, Albrecht M. Computing topological parameters of biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:282–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barabasi AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286:509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeong H, Tombor B, Albert R, Oltvai ZN, Barabási AL. The large-scale organization of metabolic networks. Nature. 2000;407:651–4. doi: 10.1038/35036627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.