Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical efficacy and nephrotoxicity along with the risk factors for acute kidney injury (AKI) associated with the parenteral polymyxin B in patients with the multidrug resistance (MDR) gram −ve infections in a tertiary Intensive care unit (ICU).

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective cohort study (March 2010-October 2011) was conducted in Medical ICU of a 23 bedded tertiary care hospital in Northern India.

Results:

Out of 71 ICU patients who were administered polymyxin B, only 32 (M:F = 1:0.8) met the inclusion criteria. Patients with concurrent administration of nephrotoxic drugs were excluded from the study. Mean age of patients was 48.53 ± 13.90 years ranging from 16 years to 68 years. 6 out of 32 (18.7%) patients progressed to AKI, whereas renal functions remained normal in 26 (81.2%) patients. No statistically significant difference was observed in mortality between AKI and non AKI patients at the end of therapy (33.3% vs. 26.9%, P value 0.756). Older age (62.33 ± 11.90 vs. 45.34 ± 2.45, P value 0.005) was found to be an independent risk factor for causing nephrotoxicity.

Conclusion:

In the present scenario of rising infections with MDR gram −ve micro-organisms, this pilot study suggests that polymyxin B can be used effectively and safely in patients not receiving other nephrotoxic drugs, with cautious administration in older patients as they are more vulnerable to nephrotoxicity caused by polymyxin B.

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, acute kidney injury, multidrug resistance gram −ve septicemia, nephrotoxicity, polymyxin B

Introduction

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is a pandemic emerging globally due to rapidly increasing microbial pathogens resistant to a wide range of antimicrobial agents.[1,2,3] MDR has been identified as the third most important problem of human health by World Health Organization.[2] Gram negative pathogens are of major concern with regards to global diffusion of antibiotic resistance, emergence of complex MDR and pan-resistant phenotypes.[4] Gram-negative organisms account for most of the nosocomial infections, including pneumonia, skin infections, intra-abdominal sepsis, urosepsis, and bloodstream infections.[5] The implicated gram −ve MDR organisms are presented by a acronym - ESKAPE- Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter.[6]

Gram-negative bacterial resistance increases the burden in the Intensive care unit (ICU) having severe impact in terms of morbidity, mortality and health-care associate costs.[7] Treating MDR gram −ve infections especially when it involves critically ill patients is a big clinical challenge. An appropriate use of older antimicrobials agents is the only therapeutic option in the face of the fact that in spite of rapid emergence of gram −ve resistance, no new antimicrobials are in the pipeline to be developed during the next decade as noted by the Infectious Diseases Society of America's “Bad Bugs, No Drugs” campaign.[8] Intravenous polymyxins (polymyxin B and colistin), an antibiotic class discovered more than 60 years ago has been reintroduced for the treatment of such infections.[9] Polymyxins have been considered as an efficacious treatment option for serious infections caused by MDR P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., K. pneumonia and Enterobacter spp. isolates. In addition, considerable activity exists against Salmonella, Shigella, Pasteurella and Haemophilus spp.[10,11] Questions about its safety has always been a matter of concern to the clinicians because of its proven nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, which are attributed to its high binding to brain and renal tissues.[11] Recent studies of polymyxin B use in MDR gram −ve infections demonstrate acceptable effectiveness and safety as compared to earlier studies that showed an estimated incidence of nephrotoxicity to be 4-22%.[12,13,14,15,16]

What are Polymyxins?

Polymyxins (polymyxin A-E) known since 1947, are a group of cationic polypeptide antibiotics. Only polymyxin B and E (colistin) have been used in clinical practice due to high toxicity of the remaining agents.[17] Polymyxin B is a lipopeptide antibiotic isolated from bacillus polymyxa it differs from colistin in having D-phenylalanine in place of D-leucine.[18] Polymyxin B is available for parenteral use as sulphate salt, colistin is available in two commercial forms-colistin sulphate for oral and topical use and sodium salt of colistin methanesulphonate (an inactive prodrug that undergoes hydrolysis in vivo and in vitro to form the active entity colistin) for parenteral/inhalational use.[17]

Mechanism of action

Polymyxins act by disrupting cytoplasmic membrane causing leakage of gram −ve organism.[12,19] Polymyxins exhibits bactericidal action by binding to the lipopolysaccharide cell membrane of gram −ve bacteria displacing the calcium and magnesium bridges that stabilize it.[20,21] Major adverse effects associated with the use of polymyxins are nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity and neuromuscular blockade. The proposed mechanism for nephrotoxicity is increased influx of cations, anions and water leading to cell swelling and lysis. Nephrotoxicity with polymyxins results in acute tubular necrosis and renal insufficiency or failure, manifested by increase in serum urea and creatinine levels associated with decrease in creatinine clearance. Nephrotoxicity caused by polymyxins in the past limited their clinical use. Nephrotoxicity of colistin seems to be less compared to that associated with polymyxin B.[18]

Limited studies have been carried out to elucidate the effectiveness and safety of polymyxin B in MDR gram −ve infection though adequate data on colistin are available. We reviewed our recent experience in the use of intravenous polymyxin B against MDR gram −ve organisms with particular attention to its nephrotoxicity and associated factors in the critical care unit.

Materials and Methods

Our study (March 2009-October 2010) was a retrospective cohort study conducted at the 23 bedded medical ICU of tertiary care hospital in Northern India. Study was approved by Institutional Ethics committee, which omitted the need for informed consent due to its retrospective nature. Medical records of all the critically ill patients with ICU - acquired infections caused by MDR gram −ve bacteria were reviewed to identify the patients who received polymyxin B between this period irrespective of the age, gender or underlying disease.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who received polymyxin B for gram −ve sepsis (either suspected or confirmed cases) for at least three consecutive days

Patients with serum creatinine less than 4 mg/dl

Patients with serum creatinine measurements available atleast one before the start of antibiotic and one during the therapy.

Exclusion criteria

Patients undergoing dialysis at the start of the therapy

Patients with obstructive renal failure

Concomitant nephrotoxic drugs (AmphotericinB, aminoglycosides, vancomycin, cyclosporine, cephalothin, Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS) tacrolimus) being administered

Patients who underwent contrast enhanced computed tomography scan.

Out of 71 patients who were administered polymyxin B for the treatment of ICU acquired MDR gram −ve infections, only 32 patients met the inclusion criteria. For 32 eligible patients, medical records were reviewed retrospectively for demographics, days of hospitalization, underlying disease, medical history, previous surgery, infection on ICU admission, source of infection, organism isolated and their antibiotic sensitivity, dosing frequency and duration of therapy, serum creatinine (baseline and highest during treatment) and outcome (recovery or death) to assess the therapeutic efficacy and nephrotoxicity of polymyxin B. Baseline serum creatinine was defined as the creatinine level on the day when initial polymyxin dose was administered. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) scoring system was used to assess patients’ severity of illness at the time of admission.[22]

Administration of polymyxin B

All patients (n = 32) in the study received intravenous polymyxin B for MDR gram −ve sepsis resistant to carbapenems. Starting dose of polymyxin B was given as per manufacturer's recommendations that is 5 lac units intravenously 8 h (15,000-25,000 IU/kg/day).[23] Dosage adjustment was carried out according to creatinine clearance in patients progressing to renal dysfunction. Creatinine clearance was calculated using the Cockcroft and Gault formula.[24]

Primary efficacy end points were resolution of sepsis and survival. Nephrotoxicity after drug therapy was assessed by Risk (R), Injury (I), and Failure (F) and two outcome classes, Loss (L) and End stage kidney disease (E) according to RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury (AKI) [Table 1].[25]

Table 1.

RIFLE criteria for AKI grading

Factors associated with nephrotoxicity like age, polymyxin dose, duration of treatment, baseline creatinine, and days of hospitalization were also studied.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data were carried out using unpaired student t-test, one-way ANOVA, bonferroni's post-hoc, and Fisher test. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data were presented as % or mean ± SD.

Results

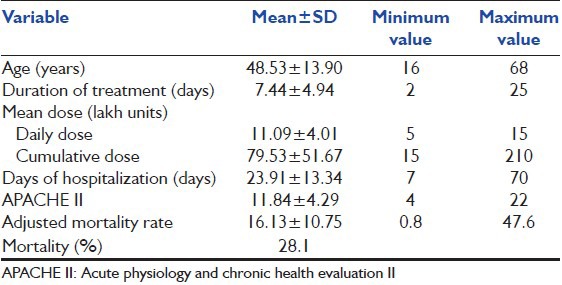

Present study has been conducted on all patients who received polymyxin B intravenously for treatment of an ICU-acquired MDR gram −ve infection. Patients undergoing dialysis at the start of the therapy, with pre existing obstructive renal failure and having concomitant nephrotoxic drugs were not included in the study. Mean age of patients was 48.53 ± 13.90 years ranging from 16 years to 68 years [Table 2].

Table 2.

Description of study population

A. baumannii was the most frequent infecting organism in 26 (81.2%) patients. One patient each was infected with E. coli, P. aeruginosa and staphylococcus epidermidis. Polymicrobial infection was seen in 3 (9.30%) patients. Major bacterial isolation sites were blood (37.5%), abdomen (28.2%), lungs (18.8%), skin and soft tissue (12.5%), and urinary tract (3.12%).

6 out of 32 (18.7%) patients progressed to whereas renal functions remained normal in 26 (81.2%) patients. Out of six patients with the renal dysfunction after polymyxin B administration, five patients developed “risk”, whereas only one patient developed “renal injury” as per RIFLE scores. Older age (62.33 ± 11.90 vs. 45.34 ± 2.45, P value 0.005) was found to be an independent factor for causing nephrotoxicity [Table 3]. No significant association was observed between polymyxin dose, duration of treatment, baseline creatinine, and days of hospitalization with nephrotoxicity.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of parameters comparing patients with and without AKI after therapy

9 out of 32 (28.1%) patients died, whereas 23 (71.9%) patients survived at the end of the therapy. Two out of 6 (33.3%) AKI and 7 out of 26 (26.9%) non AKI patients died, at the end of the treatment with no statistically significant difference (P value 0.756) [Table 3].

Discussion

Recent data on polymyxin B in critically ill patients for the treatment of serious MDR gram −ve infections is limited, but demonstrate acceptable effectiveness and considerably less toxicity than was reported in older studies. Hence, our study is an addition to the meager data about polymyxin B use in MDR gram −ve infections.

To our knowledge, our study is the only study carried out on critically ill patients who were not on nephrotoxic drugs. As nephrotoxic drugs had been a major confounding factor and it was eliminated in our study by strictly excluding patients taking nephrotoxic drugs.

Our study results demonstrated 18.7% incidence of nephrotoxicity with the use of polymyxin B, which is comparable to observed nephrotoxicity in earlier studies ranging from 4% to 22%. In concordance with the other studies showing mortality rate of 20-52%, our study reported overall 28.1% mortality [Tables 3 and 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of studies demonstrating mortality and nephrotoxicity with polymyxin B

Our study results demonstrated older age as an independent factor, as observed in past studies [Table 3]. No significant association was observed between polymyxin dose, duration of treatment, baseline creatinine, and days of hospitalization with nephrotoxicity in Sobieszczyk and Ouderkirk studies.[13,14] In contrast, a study carried out by Mendes et al. showed that higher baseline creatinine along with age is a contributing factor for development of nephrotoxicity due to polymyxin B.[12]

Mortality was observed in 26.9% non-AKI and 33.3% AKI patients with no statistically significant difference [Table 3], other studies demonstrated association of nephrotoxicity with mortality. This can be explained by the fact that high severity of renal dysfunction, which could contribute to mortality was avoided by early preventive measures being taken in the setting where present study was undertaken. Only one patient developed renal injury whereas failure was not observed in any patient. Polymyxin B had been used judiciously in appropriate dose and duration according to ideal body weight. Further, dose was adjusted daily based on daily monitoring of renal functions such as creatinine clearance and blood urea nitrogen. Intravenous fluid resuscitation was adequately carried out according to central venous pressure monitoring.

Major draw backs of our study are the small sample size, retrospective nature and lack of comparators. Reason for the small number in our study can be attributed to the restricted use of polymyxin B in critically ill patients and strict exclusion criteria. This study is a pilot study to assess the impact of polymyxin B on disease outcome and prevalence of nephrotoxicity. More exploratory prospective controlled trials are necessary to provide sufficient evidence about efficacy and safety of polymyxin B for their use in clinical practice.

In conclusion, in the present scenario of rising infections with MDR gram −ve bacteria, this pilot study suggests that polymyxin B can be effectively and safely used in patients not receiving other nephrotoxic drugs, with cautious administration in older patients as they appear to be more vulnerable to nephrotoxicity caused by the drug.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Medical ICU team of Fortis Hospital, Mohali with special thanks to Dr. Deepak Bhasin and Dr. Harpal Singh for their continuous and intense co-operation to conduct the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Levy SB, Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: Causes, challenges and responses. Nat Med. 2004;10:S122–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassetti M, Ginocchio F, Mikulska M. New treatment options against gram-negative organisms. Crit Care. 2011;15:215. doi: 10.1186/cc9997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosgrove SE. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: Mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(Suppl 2):S82–9. doi: 10.1086/499406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossolini GM, Mantengoli E, Docquier JD, Musmanno RA, Coratza G. Epidemiology of infections caused by multiresistant gram-negatives: ESBLs, MBLs, panresistant strains. New Microbiol. 2007;30:332–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trivedi TH, Sabnis GR. Superbugs in ICU: Is there any hope for solution? J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:623–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice LB. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: No ESKAPE. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1079–81. doi: 10.1086/533452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta A, Rosenthal VD, Mehta Y, Chakravarthy M, Todi SK, Sen N, et al. Device-associated nosocomial infection rates in intensive care units of seven Indian cities. Findings of the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) J Hosp Infect. 2007;67:168–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talbot GH, Bradley J, Edwards JE, Jr, Gilbert D, Scheld M, Bartlett JG, et al. Bad bugs need drugs: An update on the development pipeline from the Antimicrobial Availability Task Force of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:657–68. doi: 10.1086/499819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kvitko CH, Rigatto MH, Moro AL, Zavascki AP. Polymyxin B versus other antimicrobials for the treatment of pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:175–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gales AC, Jones RN, Sader HS. Contemporary activity of colistin and polymyxin B against a worldwide collection of Gram-negative pathogens: Results from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2006-09) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2070–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landman D, Georgescu C, Martin DA, Quale J. Polymyxins revisited. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:449–65. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendes CA, Cordeiro JA, Burdmann EA. Prevalence and risk factors for acute kidney injury associated with parenteral polymyxin B use. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1948–55. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouderkirk JP, Nord JA, Turett GS, Kislak JW. Polymyxin B nephrotoxicity and efficacy against nosocomial infections caused by multiresistant gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2659–62. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2659-2662.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sobieszczyk ME, Furuya EY, Hay CM, Pancholi P, Della-Latta P, Hammer SM, et al. Combination therapy with polymyxin B for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:566–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holloway KP, Rouphael NG, Wells JB, King MD, Blumberg HM. Polymyxin B and doxycycline use in patients with multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections in the intensive care unit. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1939–45. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramasubban S, Majumdar A, Das PS. Safety and efficacy of polymyxin B in multidrug resistant Gram-negative severe sepsis and septic shock. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12:153–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.45074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zavascki AP, Goldani LZ, Li J, Nation RL. Polymyxin B for the treatment of multidrug-resistant pathogens: A critical review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:1206–15. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. Colistin: The revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1333–41. doi: 10.1086/429323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, et al. Colistin: The re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:589–601. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans ME, Feola DJ, Rapp RP. Polymyxin B sulfate and colistin: Old antibiotics for emerging multiresistant gram-negative bacteria. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:960–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.18426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermsen ED, Sullivan CJ, Rotschafer JC. Polymyxins: Pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and clinical applications. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:545–62. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mumbai: Samarth Life Sciences private limited; 2010. Product Information. Inj. Polymyxin B sulphate BP 50,000 units, Samarth Poly B. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup. Acute renal failure-definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: The Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–12. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]