Abstract

Background:

Self-extubation is a common event in intensive care units (ICUs) world-wide. The most common factor attributed in various studies is lack of optimal sedation. However, the factors that lead to this inadequacy of sedation are not analyzed.

Aims:

The present study aimed to evaluate the determinants of factors leading to self-extubation in our ICU. Relation of patient profile, nature of sedation and any diurnal variation in extubation frequency was analyzed

Materials and Methods

Retrospective explorative analysis was carried out for patients admitted to ICU from January 2011 to January 2012. Information from medical records for the above parameters was extracted and descriptive statistics was used for assessing the outcomes.

Results:

In the present study, there was a higher incidence of self-extubation in ventilated ICU patients during the changeover periods of the ICU staff. There was no relation of frequency of self-extubation with the medications used for sedation once the sedation was titrated to a common endpoint. A higher incidence of self-extubation was seen in the surgical and younger age group of patients.

Conclusions:

It is recommended that the duty shift finishing time of ICU staff (medical and paramedical) staff should be staggered and should have minimal overlap to prevent self-extubation. A continuous reassessment of level of sedation of patients independent of the type sedative medication should be carried out.

Keywords: Duty shifts intensive care unit staff, sedation in intensive care unit, self-extubation in intensive care unit

INTRODUCTION

Self-extubation is a common event in the intensive care units (ICUs) throughout the world. The presence of an endotracheal tube is a constant strong irritant for the patient. From a clinician's perspective, providing analgesia and sedation for preventing self-extubation is a double-edged sword. On one hand, adequate sedation can easily prevent self-extubation; however, at a cost of increased incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP)[1] and increased mechanical ventilatory days.[2] On the other hand, light sedation prevents the above complications but is likely to be associated with higher rates of self-extubation and patient agitation.[3] A light plane of sedation can lead to severe ventilator patient asynchrony and defeat the purpose to ventilatory support itself.

Achieving optimal sedation is an idealistic goal; however, due to inter-patient variation of required doses of sedatives, titration has always been difficult. The nature and degree of sedation is governed by the neurological and hemodynamic status of the patient. In terms of intubated patient sedation should be enough so that the patient tolerates the endotracheal tube without becoming unresponsive. Prevention of self-extubation in limited sedation by use of restriction of patient limb movements may have ethical concerns. Attitude and alertness of medical and para-medical staff can have a major influence on preventing self-extubation related catastrophes. In the present retrospective study, we evaluated various factors influencing the self-extubation of patients in a medical/surgical ICU of a tertiary care center during a period of 1 year.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The analysis was conducted after obtaining departmental ethical clearance. We used a retrospective exploratory study design. Our patients comprised of adults aged between 18 and 85 years admitted to Level III, medical/surgical ICU in our tertiary care center. Data records of patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation more than 24 h were analyzed and information relevant to the present study was noted. All patients who were either intubated in the ICU or were intubated prior to shifting to ICU were included in the study.

Data collection

The analysis was carried out for patients admitted to ICU from January 2011 to January 2012. As a routine practice the doctors on duty maintain a separate record of all the accidental and self-extubations in our ICU. The information recorded includes the demographic profile, diagnosis, medication being used for sedation, level of sedation charted at the time of or immediately before extubation, likely reason for the event and the possible ways to prevent such an event.

For the present study, self-extubation was defined as voluntary, deliberate removal of endotracheal tube by the patient himself. Only cases of self-extubation were included in the present study. Any extubation occurring at the time of repositioning or a procedure being performed by the doctor/nurse, where patient did not deliberately pull out the endotracheal tube were labeled as accidental extubation and were not included in the present analysis.

Patients on the mechanical ventilation under paralysis by neuromuscular blockers were also excluded from the analysis. The nurse patient ratio in our ICU is 1:1 any deviation from this practice at the time of self-extubation was noted

The level of sedation that is routinely targeted in our ICU is Ramsay score of 2-3 (Patient tranquil, obeying commands to asleep).[4] During the data extraction patient's identity, medical record number was kept confidential.

Data analysis

All the data collected were analyzed using the SPSS 20 (IBM Inc.) for Macintosh. Descriptive statistics were computed for all the variables. Graphical representation for parameters was constructed using the SPSS and Microsoft Excel. Chi-square test was used for analysis of non-parametric variables.

RESULTS

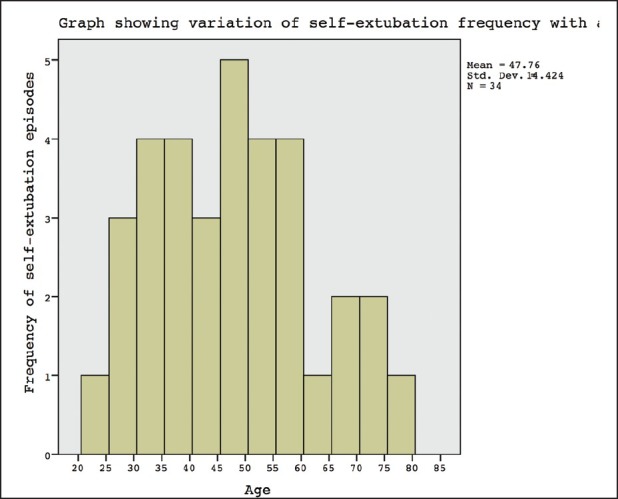

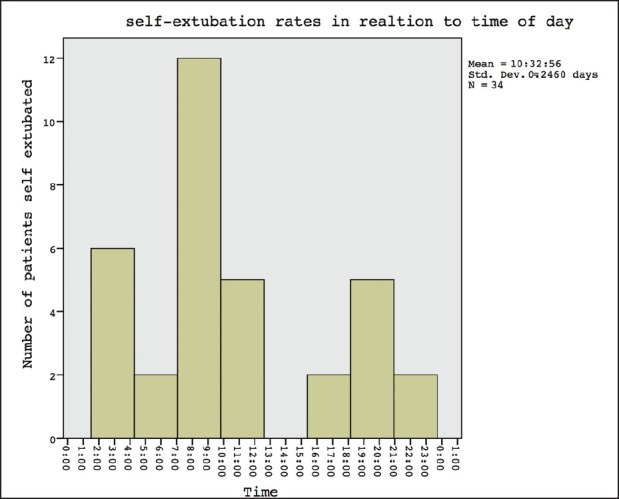

A total of 322 patients were admitted to ICU of which 273 were intubated and received sedation. Rest 49 patients either were not intubated or tracheostomized or were paralyzed; thus, extubation for these patients was not considered. Overall 12.4% incidence of self-extubation was found with thirty-four self-extubation episodes documented in the records. Eleven patients were females and the rest twenty-three were males. The mean age of all patients with documented self-extubation was 47.76 ± 14.24 years, patients between the age group 30-50 years accounted for 47% of the total episodes [Figure 1]. Twenty patients were post-surgical and 14 were medical patients. The relation of time with a number of extubation showed a bimodal peak with 12 self-extubations (35%) occurring between 7 am to 10 am and 5 self-extubations (14.7%) between 6 pm to 9 pm [Figure 2]. Twenty of 34 patients (58.9%) were surgical, shifted to ICU in view of major surgeries or intraoperative complications, the rest 14 (41.1%) patients suffered from medical disorders necessitating need of mechanical ventilation.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the number of patient's self-extubated and age

Figure 2.

Graph Showing Bimodal peak of self-extubation rates in relation to time of day

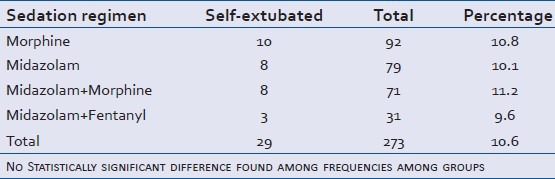

During their ICU stay 79 (28.9%), 71 (26%), 31 (11.3%) and 92 (33.6%) patients were receiving or had received midazolam, midazolam + morphine, midazolam + fentanyl and morphine infusions respectively to titrate sedation levels to Ramsay score of 2-3. Of these five patients at the time of self-extubation were receiving no sedation; either due to planned extubation (3/5) or for neurological assessment after sedation free period (2/5). Eight patients were receiving midazolam infusion, three patients were receiving combination of fentanyl/midazolam infusion, ten patients were receiving morphine infusion and rest eight patients were on a combined midazolam and morphine infusion [Table 1]. The above infusions were being titrated to a Ramsay sedation score of 2-3. On comparison of frequency of extubation related to type of sedation using the Chi-square test, no statistically significant difference was found among any group (P < 0.05 being considered as statistically significant).

Table 1.

Sedation targeted to Ramsay sedation score 2/3

The most common cause documented as a reason for self-extubation by the doctor on duty was inadequate sedation (21/29), for rest 8 patients an immediate procedure arousing an adequately sedated patient was the attributable cause (5 of 8-Endotracheal tube (ETT) suctioning, 3 of 8 patient repositioning due to X-ray or cleaning). In these 8 patients the extubation was not labeled as accidental as these were carried out deliberately by the patients and occurred only after the procedure had been performed. Two patients had been diagnosed with ICU psychosis (both >65 years) and self-extubated despite sedation and physical restrains (soft-wrist and hand-ties). Among the total 34 self-extubating patients, 32 had to be re-intubated immediately or subsequently due to onset of hypoxia, hypercarbia or dyspnea. Two patients who did not need re-intubation were post-surgical patients in whom extubation was already planned.

DISCUSSION

In the present analysis, the bimodal peak of self-extubation (35% between 7:00 and 10:00 am and 14.7% between 6:00 pm and 9:00 pm) occurred during the duty shifting times of the ICU staff– all nurses, paramedics and doctors. Earlier studies have reported a higher incidence of self-extubation only during early morning hours.[5] No diurnal variation has been reported previously until the date. The high extubation rates at these times have been attributed less sedation during these times, which is true for our ICU also. Sedation free periods have been recommended for decreasing the incidence of VAP in ventilated patients though these periods may be associated with a higher incidence of self-extubation. The timing of both the noted peaks in the present analysis corresponds to the changeover timing of the ICU staff. During the changeover time the nurses and the residents (incoming and outgoing) remain busy with patient in question, discussing management plans. This would be the most venerable period for sub-optimal sedation levels and thus is associated with increased frequency of self-extubation. Nearly, 50% of total extubation episodes showed this bimodal distribution occurring in 6 h (25% of total time). The remainder 50% events that occurred in rest 18 h (3/4th of total time) were attributed primarily to inadequate sedation due various non-specific causes such as change in patient status, infusion refilling, accidental infusion disconnection, patient manipulations etc. These remainder half of episodes, were more common between 1:30 am and 4:30 am [Figure 2]. This is consistent with the previous literature[5] and in our ICU is possibly related to the number of chest X-rays and blood sampling carried out during this time frame. Such a practice ensures that radiological films and reports are available by the time of clinical rounds for discussion.

One of the management strategies in ICUs in preventing VAP is to use sedation free periods.[6] This additionally gives the opportunity to assess the neurological status of the patient, but at a cost of reducing sedation levels. As a protocol in our ICU, sedation is stopped early morning around 6 am so that by the time attending consultant comes in ICU for rounds, the patient is weaned off the effects of sedation and further management can be planned. This probably highlights the maximal frequency of extubation in the early morning shift time, when the sedation levels are lowered and over is going on. However, during early morning hours, the ICU patients are repositioned and cleaning is carried out. This manipulation alters the patient's sedation state due to stimulation and thus contributes to increased morning self-extubation. The suggested modification to prevent these events is to have minimal overlap between paramedical and medical duty shift times. If one team is busy the other can be alert to titrated sedatives. Although, continuous infusion pumps are used to administer sedation the infusion rates need to be readjusted frequently in an ICU. The sedation target of Ramsay Sedation score (RSS) of 2/3 is based on a subjective scale and sedation requirements vary with patient condition in critical care settings.[7] Maintaining an optimal level of sedation needs regular reassessment. This is likely to be affected during the changeover procedure, which could lead to a decrease in sedation resulting in self-extubation.

The nature of sedative medications used in the present study did not affect the self-extubation rates. In the present study, 29 patients who self-extubated were receiving one of the four different combinations of sedatives [Table 1]. The reason for using the different combinations of medications in our ICU is because using the opioids in addition to midazolam adds to analgesia for the post-operative patients. However, all types of sedation used had similar incidence of self-extubation rates when targeted to Ramsay sedation score of 2/3. This highlights the fact that endpoint of sedation (Ramsay sedation scale) is more important than the type of sedation used. The pharmacology of the drugs affects the time for wearing off the sedative effect but once the drugs are titrated to RSS, no difference in terms of self-extubation frequency was found in the present study. Previous studies have documented increased agitation in patients receiving benzodiazepines and thus, increased incidence of self-extubation.[8] However, in our ICU, we use haloperidol frequently; thus, the above agitation related increased incidence was not seen in the present analysis. Two patients (age >65 years) developing increased agitation were on midazolam infusion and had associated hepatic dysfunction, thus haloperidol was avoided in them. This can likely be attributed to above concerns of agitation form midazolam infusions in elderly.[9]

The present study highlights an interesting outcome of relation of time of self-extubation to frequency of episodes. The dual peaks in the frequency in number of patients self-extubation corresponds to time of change of duty shifts of ICU staff. In our tertiary care ICU, the paramedical staff of night shift is relieved off duty at 7:00 am and the medical staff (two anesthesia residents) is relieved at 8:30 am after giving over to the next team. Twelve episodes (35%) of self-extubation episodes correspond to this time interval. The night shifts are changed over at corresponding times 7:00 pm for paramedical and 8:30 pm for medical staff. This time interval accounted for another 15% of episodes. Hence, almost 50% of total extubation in the year occurred during staff shift change over time. In our 12-bedded ICU, even if, resident doctors spend 5-8 min on each patient the duration of this change over varies from 45 min to 90 min depending upon the severity and number of patients in the ICU. The joining paramedical staff universally checks previous duty notes, drug documentations, and residual infusions and takes time to fully attend to the patient.

Previous literature documents self-extubation rates of 3-14%, similar to our analysis (12.4%).[10,11] Universally multiple studies conducted on the factors causing self-extubation have attributed it to inadequate sedation without analyzing contributors to this inadequate sedation. Furthermore, they have neglected to analyze any diurnal variation in the number of extubations. Subjective scales such as Ramsay sedation scale and Richmond agitation scale etc. often guide sedation in ICU.[4] These scales show marked inter-individual variability and thus targeted sedation in ICU needs frequent vigilant monitoring and titration. Furthermore, alteration in attention span of ICU clinician is likely to change the sedation levels in patients. Multiple prospective and retrospective trials have attributed inadequate sedation as the primary cause to patient self-extubation in ICU.[12,13] During the change over time residents (incoming and outgoing) remain busy with patient in question, discussing management plans. This would be the most venerable period for sub-optimal sedation levels and thus is associated with an increased frequency of self-extubation.

Age group with maximal frequency (16/34) of self-extubation was between 30 and 50 years [Figure 1]. Literature on the effect of age in rates of self-extubation is scarce.[14] The possible reason for lower rates of self-extubation seen in patients younger than 30 years in a medico-surgical ICU is likely that these patients often are post-surgical and remain intubated for much shorter times than compared to patients in the age group 30-50 years (more medical patients). Patients older than 50 years often have multiple co-morbidities and are much more sensitive to effect of sedatives than middle aged patients. Thus, they are less likely to be under-sedated and self-extubate. A similar higher incidence was found among surgical patients possibly due to either inadequate sedation due to pain or lesser comorbidities in this subset of patients.

As sedation scores tend to drop immediately after patient disturbance, eight patients’ extubated post-procedures; thus, it is advised that prior to manipulation a Ramsay score of at least three must be targeted in these patients, A Ramsay sedation score of two may become inadequate immediately following the procedure and contribute to self-extubation.

The diurnal variation seen in frequency of self-extubation in the present analysis highlights an important outcome to prevent self-extubation in ICU. Although, the crux of the problem of self-extubation is inadequate sedation, hand over time overlap is a factor that potentiates this. The duty shifts of medical and paramedical staff should be timed such that they have minimal overlap. Furthermore, once the sedation is titrated to and endpoint the nature of sedative used does not seem to affect the self-extubation rates.

CONCLUSIONS

In the present study, there was a higher incidence of self-extubation in ventilated ICU patients during change over periods of the ICU staff. There was no relation of frequency of self-extubation with the medications used for sedation once the sedation was titrated to a common endpoint. There was a higher incidence of self-extubation in the surgical and younger age group of patients. It is recommended that the duty shift hours of the ICU staff should be staggered and should have minimal overlap to prevent self-extubation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nseir S, Makris D, Mathieu D, Durocher A, Marquette CH. Intensive Care Unit-acquired infection as a side effect of sedation. Crit Care. 2010;14:R30. doi: 10.1186/cc8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gommers D, Bakker J. Medications for analgesia and sedation in the intensive care unit: An overview. Crit Care. 2008;12(Suppl 3):S4. doi: 10.1186/cc6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wunsch H, Kress JP. A new era for sedation in ICU patients. JAMA. 2009;301:542–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta S, McCullagh I, Burry L. Current sedation practices: Lessons learned from international surveys. Anesthesiol Clin. 2011;29:607–24. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulain T. Unplanned extubations in the adult intensive care unit: A prospective multicenter study. Association des Réanimateurs du Centre-Ouest. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1131–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9702083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig SM, Truwit JD. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:637–57. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00051-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svenningsen H, Egerod I, Videbech P, Christensen D, Frydenberg M, Tønnesen EK. Fluctuations in sedation levels may contribute to delirium in ICU patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:288–93. doi: 10.1111/aas.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tung A, Tadimeti L, Caruana-Montaldo B, Atkins PM, Mion LC, Palmer RM, et al. The relationship of sedation to deliberate self-extubation. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13:24–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(00)00237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Grounds RM, Sarapohja T, Garratt C, Pocock SJ, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam or propofol for sedation during prolonged mechanical ventilation: Two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2012;307:1151–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Moura EB, De Araújo Neto JA, De Oliveira Maia M, Lima FB, Bomfim RF. Assessment of the impact of unplanned extubation on ICU patient outcome. Crit Care. 2011;15(Suppl 1):P169. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vassal T, Anh NG, Gabillet JM, Guidet B, Staikowsky F, Offenstadt G. Prospective evaluation of self-extubations in a medical intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 1993;19:340–2. doi: 10.1007/BF01694708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mion LC, Minnick AF, Leipzig R, Catrambone CD, Johnson ME. Patient-initiated device removal in intensive care units: A national prevalence study. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2714–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000291651.12767.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods JC, Mion LC, Connor JT, Viray F, Jahan L, Huber C, et al. Severe agitation among ventilated medical intensive care unit patients: Frequency, characteristics and outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1066–72. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang YT. Factors leading to self-extubation of endotracheal tubes in the intensive care unit. Nurs Crit Care. 2009;14:68–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2008.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]