Abstract

Background:

In resource-poor settings, the management of neuromyelitis optica (NMO) and NMO spectrum (NMOS) disorders is limited because of delayed diagnosis and financial constraints.

Aim:

To device a cost-effective strategy for the management of NMO and related disorders in India.

Materials and Methods:

A cost-effective and disease-specific protocol was used for evaluating the course and treatment outcome of 70 consecutive patients.

Results:

Forty-five patients (65%) had a relapse from the onset and included NMO (n = 20), recurrent transverse myelitis (RTM; n = 10), and recurrent optic neuritis (ROPN; n = 15). In 38 (84.4%) patients presenting after multiple attacks, the diagnosis was made clinically. Only 7 patients with a relapsing course were seen at the onset and included ROPN (n = 5), NMO (n = 1), and RTM (n = 1). They had a second attack after a median interval of 1 ± 0.9 years, which was captured through our dedicated review process. Twenty-five patients had isolated longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM), of which 20 (80%) remained ambulant at follow-up of 3 ± 1.9 years. Twelve patients (17%) with median expanded disability status scale (EDSS) of 8.5 at entry had a fatal outcome. Serum NMO-IgG testing was done in selected patients, and it was positive in 7 of 18 patients (39%). Irrespective of the NMO-IgG status, the treatment compliant patients (44.4%) showed significant improvement in EDSS (P ≤ 0.001).

Conclusions:

Early clinical diagnosis and treatment compliance were important for good outcome. Isolated LETM was most likely a post-infectious demyelinating disorder in our set-up. NMO and NMOS disorders contributed to 14.9% (45/303) of all demyelinating disorders in our registry.

Key Words: Demyelinating disease registry, immunosuppression, India, neuromyelitis optica, neuromyleitis optica spectrum disorders

Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is a distinct form of idiopathic central nervous system (CNS) demyelinating disorder that targets the optic nerves and spinal cord. The clinical presentations, pathological and radiological features, and choice of disease modifying therapies were different from that for multiple sclerosis (MS). The term NMO spectrum (NMOS) disorder typically includes NMO-IgG seropositive single or recurrent longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM), recurrent or simultaneous bilateral OPN, and LETM or OPN associated with systemic autoimmune disease; the list is continuously expanding.[1] Disability in NMO is attack-related, unlike in MS, where disability gradually accrues during the progressive phase of the disease. It is only logical that management strategy for NMO and NMOS should center around early diagnosis and attack prevention. Immunosuppressive therapy is the mainstay of treatment and drugs such as corticosteroids, azathioprine,[2] mycophenolate mofetil,[3] and rituximab[4] have been reported to be useful.

In resource-poor countries, patients with chronic illnesses including demyelinating CNS disorders receive specialist care, often in advanced stage of the disease. Cost of investigations, hospitalization, and treatment have to be borne by patients. Respect for traditional/alternative medicine motivates patients to opt for the same when there is a lack of improvement and or financial constraints. We are sharing our experiences with the management of NMO and NMOS registered in the Mangalore demyelinating disease registry[5] in south India. We propose an algorithm for cost-effective management of such condition, which could be adopted in countries with similar health resources.

Materials and Methods

Clinical case selection

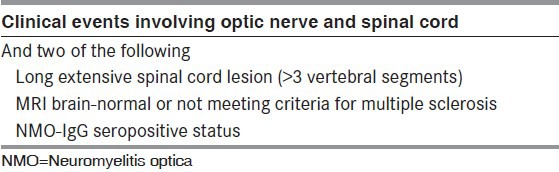

All consecutive patients with NMO, isolated ATM with LETM, recurrent transverse myelitis (RTM) and recurrent optic neuritis (ROPN) with normal brain imaging were included. NMO was diagnosed [Table 1] by Wingerchuck 2006 criteria.[6] The definition of LETM was satisfied when MRI of the spinal cord showed contiguous demyelinating lesions extending more than 3 vertebral segments.[6] This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and informed consent was obtained prior to enrolling patients.

Table 1.

Wingerchuck diagnostic criteria for NMO (2006)

Evaluation protocol

Patients in the Mangalore demyelinating disease registry[5] were entitled to subsidized hospitalization and MRI. Azathioprine (AZA) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) were made available at concessional rates. Patients were clinically evaluated and expanded disability status scale (EDSS)[7] scored 6 weeks after an attack and at subsequent visits. Lumbar puncture was done in selected patients to exclude alternative etiology. Visual acuity (VA) and visual evoked potentials (VEP) were recorded. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and the spine was done at least once. In addition, ROPN patients had MRI brain after their last attack. Serum NMO-IgG was tested among patients who could afford the same, especially among those who arrived at our center with a recent relapse and had no prior parenteral steroids. Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and HIV was tested in all patients.

Treatment protocol

Acute treatment

Intravenous (IV) methyl prednisolone was given for 5 days (1 g/day) during the acute phase. Plasma exchange (PE) was done for poor responders (no motor improvement by at least 1 grade in the affected limbs within 5-7 days of IV steroids), depending upon the affordability.

Maintenance treatment

All patients were started on oral steroids at an initial dose of 0.5 mg/day. Steroids were stopped within 3-6 months. Oral immunosuppressants (OIS) in the form of AZA 2-2.5 mg/kg daily or MMF 1-3 g/day were started simultaneously in all suitable patients who had a relapsing course. The cost of therapy determined the choice of OIS (AZA was cheaper). Immunosuppressant treatment was deferred in patients with uncontrolled glucocorticoid-induced diabetes, urinary tract infection, or other co-morbid conditions that was difficult to monitor from their homes.

Following the first review (4-6 weeks after admission and discharge), the patients were contacted by telephone at periodic intervals by a non-medical assistant trained exclusively for this purpose. The patients were encouraged to visit our hospital every 3-6 months or earlier if they felt unwell. The EDSS score was documented during every visit. For those who could not visit, the degree of disability was self-reported. Blood counts and biochemistry were repeated at specified intervals in local laboratories and results were informed telephonically. A network of general practitioners could be established in some areas, and they were contacted to oversee the treatment occasionally.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics including mean, median, and standard deviations were calculated. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparing EDSS in the treated group before and after OIS therapy.

Results

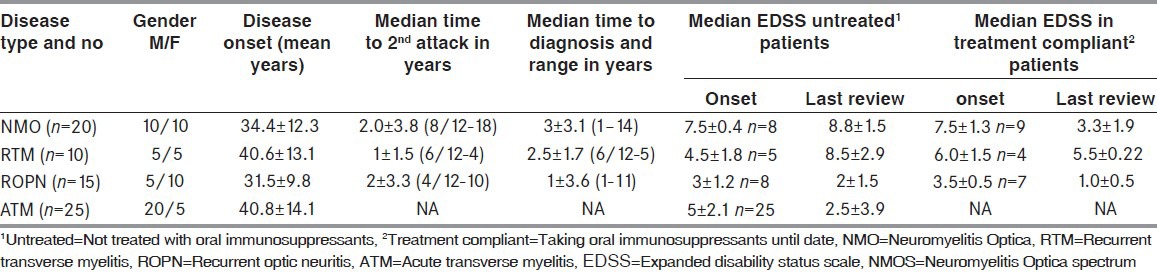

Seventy patients were noted to belong to NMO (n = 20) and NMOS (n = 50) disorder in our registry. The latter included ATM (n = 25), ROPN (n = 15), and RTM (n = 10). The total number of demyelinating disorders seen during this period was 303 [including MS (n = 145), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (n = 20), clinically isolated syndrome (n = 62), and tumefactive demyelination (n = 6). The age of onset, time to second attack, time to diagnosis, and period of follow-up was noted [Table 2]. Thirty-two patients seen from the onset included all cases of ATM (n = 27) and ROPN (n = 5). Two patients with ATM had recurrent attacks within the ensuing 2 years, including a 48-year-old woman with recurrent LETM after 8 months and a 54-year-old male with bilateral OPN 13 months after recovering poorly from myelitis. Both were analyzed under RTM and NMO category respectively. All surviving 20 (80%) patients regained a good functional outcome. Thirteen patients were asymptomatic, 2 walked with restriction (<500 m), and the remaining 5 required unilateral assistance after a median follow-up. Antecedent illness preceding ATM included fever (n = 3), upper respiratory infection (n = 2), mumps (n = 1), and varicella zoster (n = 1).

Table 2.

Clinical demographics and outcome in NMO and NMOS disorders

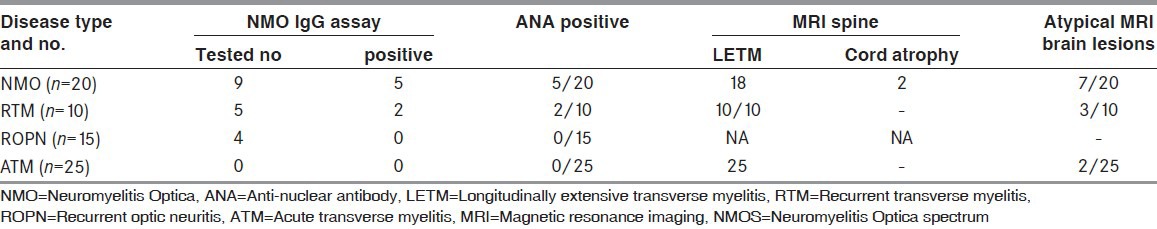

The investigations done were summed up in Table 3. A definitive diagnosis could be made in all patients who presented after multiple attacks based on Wingerchuck criteria. Twelve patients were non-responders for IV steroids and had a median EDSS of 8.5 at entry. They were not given maintenance therapy due to co-morbid illness and expired within a median period of 1 ± 0.8 years [Table 3]. Another 11 patients were unwilling to start OIS, including 2 NMO and 2 RTM patients who refused therapy and had no further attacks. They walked with restriction (<500 m) at a median follow-up of 2.7 ± 1.8 years. Patients with ROPN who retained good vision after infrequent attacks (n = 2) and those who registered after 2.5-3 asymptomatic years (n = 3) were not initiated on AZA or MMF.

Table 3.

Investigations for NMO and NMOS disorders

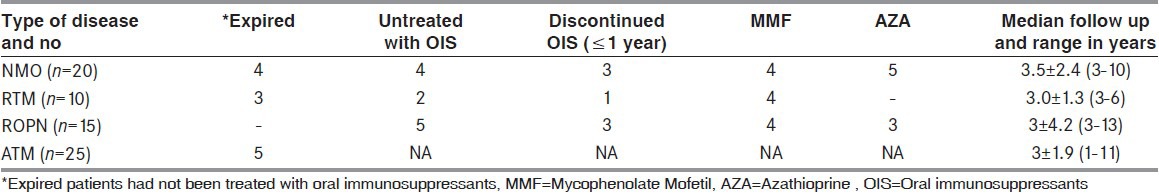

Twenty-seven patients were identified from the original cohort to receive AZA (n = 17) and MMF (n = 10). Five patients discontinued AZA permanently [Table 4] due to gastrointestinal side effects and 2 switched to MMF. Patients in the treated group (n = 20) had significant improvement in the EDSS score measured at last follow-up while on OIS therapy (P < 0.001). This effect was best seen in NMO (P = 0.005) and ROPN (P = 0.01) but not in RTM (P = 0.22) patients.

Table 4.

Over view of treatment and follow.up

One NMO patient who discontinued treatment had a striking clinical course. This 22-year-old male had 2 episodes of LETM interspersed with OPN in the preceding 3 years. He was evaluated by authors PL and SR during the third attack of LETM, which rendered him quadriplegic and ventilator dependent. Brain MRI showed a solitary large tumefactive brain lesion with clinical evidence of raised intracranial tension. He recovered well and received maintenance therapy with AZA, which he discontinued after 18 months. Five years later, he remains asymptomatic on regular follow-up. Three ROPN patients who discontinued AZA continued to take intermittent courses of oral steroids when vision deteriorated. In these patients, VA in the worst-affected eye ranged from 6/36 to 6/60.

Discussion

Reports from India in the pre-MRI era suggested a high-optic nerve and spinal cord involvement in Indian MS,[8] similar to that from Southeast Asia.[9] This led to speculations that NMO prevalence in India may be high. Jacob et al.,[10] compiled published literature on MS and related demyelinating diseases in India and suggested that NMO may represent 9-24% or even higher of all demyelinating disorders. In our study from south India, we showed for the first time that NMO and spectrum disorders is likely to constitute approximately 15% of all demyelinating disorders. While it is much lower than what is reported in Southeast Asia[11] (up to 40%), prevalence in India is in concordance with that of African American[12] and Brazilian populations.[13]

Despite our best efforts, we were able to maintain chronic immunosuppressant therapy in only 20 of 45 (44.4%) patients deemed suitable for the treatment. However, we were successful in retaining all surviving patients (58/70; 82.8%) for regular follow-up. The authors have treated isolated LETM as a post-infectious demyelinating disorder. Only 2 patients had recurrence within the ensuing 2 years and both the events were captured through our periodic review. In India, isolated ATM is an important cause of non-compressive myelopathy[14] and recurrence is uncommon.[15] Antecedent viral infection was present in some of our patients, but it may not differentiate post-infectious ATM from NMOS.[16] All NMO and NMOS patients who died in our cohort had poor motor recovery that has been previously noted.[17] Most patients succumbed to sepsis, resulting from urinary and respiratory tract infections at home or local hospitals. Only 3 patients with steroid unresponsive myelitis could be given PE.[18]

Treatment compliant patients had a much better outcome, particularly for the NMO and ROPN subset [Table 1]. Nine patients remained well despite the lack of or discontinued immunosuppressant therapy. There have been earlier reports from India of NMO and NMOS phenotype disorders, which had a relatively benign outcome.[19] As we did not test for NMO-IgG in all patients, we cannot be sure whether some of these patients had milder forms of the disease or a steroid responsive demyelinating disorder of unknown etiology. Males (n = 40) outnumbered female (n = 30) patients in our study. In our set-up, it is possible that males were given preference over females for hospitalization and treatment.[20]

This study is limited by its small number. We restricted NMO-IgG testing to patients who could afford it. The varying sensitivity of assays,[21] the need for multiple testing, and the use of more than one technique to increase seropositive rates[22] makes it impractical to include NMO-IgG testing routinely for the diagnosis of NMO and NMOS disorders in resource-poor countries. At our center, the majority of financially constraint patients opted for the subsidized package of hospital stay, one-time MRI scan and parenteral steroids that allowed them to complete the acute-phase treatment successfully. NMO-IgG testing was not done in the latter. Testing for NMO-IgG may have helped predict the diagnosis of a non-MS demyelinating disease in 7 patients (10%) whom we saw from onset. However, the second attack was captured in all through our systematic review and helped us intervene appropriately.

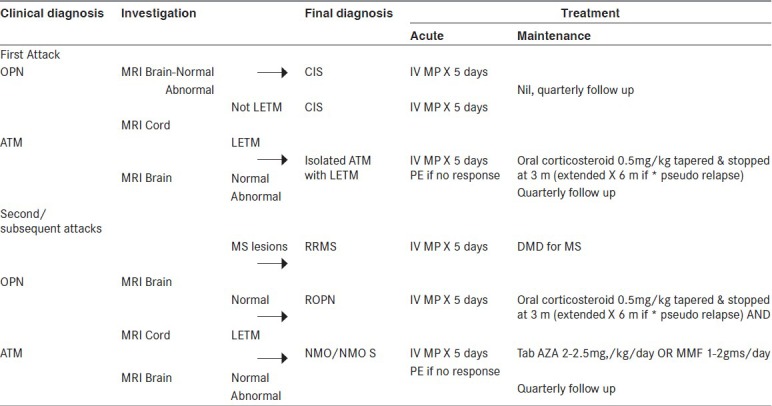

We proposed a practical algorithm for the management of such patients [Figure 1]. Our algorithm emphasizes the need to differentiate these disorders based on the clinical and MRI parameters (outlined in Wingerchuck 2006 criteria) from MS and the judicious use of OIS after establishing the relapsing nature of the disease. Our system of regular telephonic follow-up helped us sustain the treatment compliance in patients and also to gain insight into disease course, even in untreated patients. Irrespective of NMO-IgG status (data not shown), our algorithm worked well in the treatment-compliant patients.

Figure 1.

Management algorithm for NMO and NMOS disorders IV MP=Intravenous methyl prednisolone, LETM=Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, PE=Plasma exchange, DMD=Disease modifying drugs, AZA=Azathioprine, MMF=Mycophenolate mofetil, m=Month *Pseudo relapse: Deterioration of preexisting neurological deficits on tapering oral steroids

Conclusions

Despite the limitations of our study, we set up an algorithm for the management of NMO and NMOS disorders, which enables accurate diagnosis and facilitates early intervention in resource-poor settings. We relied on clinical and radiological findings to differentiate these disorders from MS and less on NMO-IgG testing for reasons mentioned. Patient selection for the treatment with chronic immunosuppressant therapy was vital, since the success of this model was based on monitoring of patients from their home settings. We believe that such a model could be useful for the treatment of patients in countries with similar health-resource constraints as ours.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil

References

- 1.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:805–15. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandler RN, Ahmed W, Dencoff JE. Devic's neuromyelitis optica: A prospective study of seven patients treated with prednisone and azathioprine. Neurology. 1998;51:1219–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob A, Matiello M, Weinshenker BG, Wingerchuk DM, Lucchinetti C, Shuster E, et al. Treatment of neuromyelitis optica with mycophenolate mofetil: Retrospective analysis of 24 patients. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1128–33. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cree BA, Lamb S, Morgan K, Chen A, Waubant E, Genain C. An open label study of the effects of rituximab in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2005;64:1270–2. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159399.81861.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandit L, Shetty R, Misri Z, Bhat S, Amin H, Pai V, et al. Optic neuritis: Experience from a south Indian demyelinating disease registry. Neurol India. 2012;60:470–5. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.103186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BC. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66:1485–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216139.44259.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33:1444–52. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain S, Maheshwari MC. Multiple sclerosis: Indian experience in the last thirty years. Neuroepidemiology. 1985;4:96–107. doi: 10.1159/000110220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibasaki H, Kuroda Y, Kuroiwa Y. Clinical studies of multiple sclerosis in Japan: Classical multiple sclerosis and Devic's disease. J Neurol Sci. 1974;23:215–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(74)90224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob A, Boggild M. Neuromyelitis optica. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2007;10:231–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.58277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kira J. Multiple sclerosis in the Japanese population. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:117–27. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cree BA, Khan O, Bourdette D, Goodin DS, Cohen JA, Marrie RA, et al. Clinical characteristics of African Americans vs Caucasian Americans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63:2039–45. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145762.60562.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papais-Alvarenga RM, Miranda-Santos CM, Puccioni-Sohler M, de Almeida AM, Oliveira S, Basilio De Oliveira CA, et al. Optic neuromyelitis syndrome in Brazilian patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:429–35. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prabhakar S, Syal P, Singh P, Lal V, Khandelwal N, Das CP. Noncompressive myelopathy: Clinical and radiological study. Neurol India. 1999;47:294–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaurasia RN, Verma A, Joshi D, Misra S. Etiological spectrum of non-traumatic myelopathies: Experience from a tertiary care centre. J Assoc Physics India. 2006;54:445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O’Brien PC, Weinshenker BG. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic_s syndrome) Neurology. 1999;53:1107–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. Neuromyelitis optica: Clinical predictors of a relapsing course and survival. Neurology. 2003;60:848–53. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000049912.02954.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnan M, Valentino R, Olindo S, Mehdaoui H, Smadja D, Cabre P. Plasma exchange in severe spinal attacks associated with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler. 2009;15:487–92. doi: 10.1177/1352458508100837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pradhan S, Mishra VN. A central demyelinating disease with atypical features. Mult Scler. 2004;10:308–15. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1040oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazio R, Malosio ML, Lampasona V, De Feo D, Privitera D, Marnetto F, et al. Antiacquaporin 4 antibodies detection by different techniques in neuromyelitis optica patients. Mult Scler. 2009;15:1153–63. doi: 10.1177/1352458509106851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sellner J, Boggild M, Clanet M, Hintzen RQ, Illes Z, Montalban X, et al. EFNS guidelines on diagnosis and management of neuromyelitis optica. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1019–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandit L. Insights into the changing perspectives of multiple sclerosis in India. Autoimmune Dis 2011. 2011 doi: 10.4061/2011/937586. 937586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]