Abstract

Objective

To assess the survival and prognostic factors in patients with newly diagnosed incident systemic sclerosis (SSc)–associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in the modern management era.

Methods

Prospectively enrolled SSc patients in the French PAH Network between January 2006 and November 2009, with newly diagnosed PAH and no interstitial lung disease, were analysed (85 patients, mean age 64.9±12.2 years). Median follow-up after PAH diagnosis was 2.32 years.

Results

A majority of patients were in NYHA functional class III–IV (79%). Overall survival was 90% (95% CI 81% to 95%), 78% (95% CI 67% to 86%) and 56% (95% CI 42% to 68%) at 1, 2 and 3 years from PAH diagnosis, respectively. Age (HR: 1.05, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.09, p=0.012) and cardiac index (HR: 0.49, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.89, p=0.019) were significant predictors in the univariate analysis. We also observed strong trends for gender, SSc subtypes, New York Heart Association functional class, pulmonary vascular resistance and capacitance to be significant predictors in the univariate analysis. Conversely, six-min walk distance, mean pulmonary arterial and right atrial pressures were not significant predictors. In the multivariate model, gender was the only independent factor associated with survival (HR: 4.76, 95% CI 1.35 to 16.66, p=0.015 for male gender).

Conclusions

Incident SSc-associated PAH remains a devastating disease even in the modern management era. Age, male gender and cardiac index were the main prognosis factors in this cohort of patients. Early detection of less severe patients should be a priority.

Keywords: Systemic Sclerosis, Outcomes research, Treatment

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a severe complication of systemic sclerosis (SSc) and one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in this disease.1 2 Although several recent studies have suggested an improvement in the prognosis of SSc-PAH, especially since the availability of specific therapies, the overall survival at 3 years remains poor (around 50%) and worse than in patients with idiopathic PAH.3–6 Many studies have addressed the survival and prognostic factors in SSc-PAH.7 8 However, there are some issues with these studies, including the most recent ones. The first issue is that most studies are from single centres, and/or are retrospective, and/or include prevalent patients.5 9–15 To our knowledge, there are only four available multicentre prospective studies with incident patients.4 6 16 17 Indeed, we have shown that including prevalent patients, that is, patients with PAH already diagnosed at the time of enrolment in the study, was a bias as it led to an improved survival of the cohort.18 19 Therefore, to best reflect the true prognosis of SSc-PAH, it is mandatory to include only incident patients with a newly and recently diagnosed disease. The second important issue is the presence of an associated interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with SSc. We, along with others, have shown that significant ILD was an important prognostic factor in patients with SSc and pulmonary hypertension (PH).4 9 14 SSc patients with ILD-associated PH (PH-ILD) have a worse prognosis. However ILD, either limited or extensive, even without PH, also has an impact on the overall prognosis, and ILD is also one of the leading causes of death in SSc.2 20 Moreover, although the definition of PH-ILD in patients with SSc is rather homogenous between studies and relies mainly on lung volumes with or without the extension of the ILD on high-resolution CT (HRCT), it must be highlighted that this definition has not been validated in SSc and is empirical. Indeed, there are currently no available data on the prognosis of SSc-PAH without any ILD at all because all previous studies mixed patients with isolated SSc-PAH without ILD, and patients with PAH and a limited ILD (as defined by mild extension on HRCT and preserved lung volumes) in the same SSc-PAH subgroup, without comparing them. The final unmet issue is the period of recruitment of patients. The most recent multicentre prospective study focusing on incident new cases of SSc-PAH has included patients between 2001 and 2006.4 There are no up-to-date data available for patients treated in the most recent modern management era, that is, since 2006.

We designed the following prospective study to address these issues. We consecutively included in the multicentre French Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Network SSc patients with newly diagnosed PAH between January 2006 and November 2009 and focused on patients without any ILD on HRCT. We assessed the clinical, functional and haemodynamic characteristics, survival and prognostic factors in these patients.

Methods

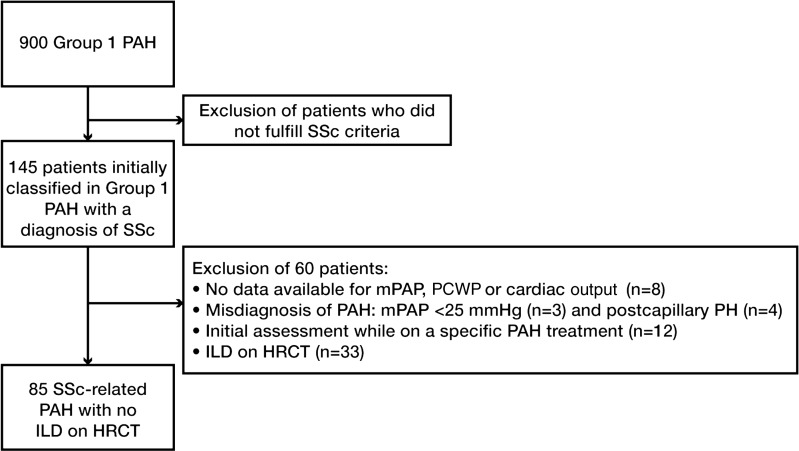

The French Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Network comprised 17 university pulmonary vascular centres and was established in 2002. All patients prospectively recruited between January 2006 and November 2009 with a diagnosis of SSc-PAH were included. This study was compliant with requirements of the Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés, and all patients provided informed consent to participate. PAH was defined as mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥25 mm Hg at rest, and pulmonary artery wedge pressure ≤15 mm Hg measured during right heart catheterisation at rest. Three patients were therefore excluded as their mPAP was <25 mm Hg. Of note, none of these three patients was classified as having a former diagnosis of PAH on exercise, and had therefore been inappropriately entered into the Registry. SSc patients fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SSc and/or the LeRoy's classification system (limited cutaneous or diffuse cutaneous SSc).21 22 Patients with overlap syndrome with another connective tissue disease (lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and myositis) were excluded. As discussed above, and to assess a homogeneous population, all patients underwent a HRCT of the chest at PAH diagnosis in order to look for the presence of ILD associated with SSc, as defined by the presence of at least one usual sign of SSc-associated ILD, that is, subpleural pure ground-glass opacity and/or interstitial reticular pattern with or without traction bronchiectasis, and/or honeycomb cysts. Presence of signs suggestive of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease was not systematically reported and was not included in the analysis. We focused on SSc patients with isolated PAH, that is, without any signs of ILD on HRCT. Patients with isolated ground-glass opacity on HRCT were excluded (although this can also be a non-specific finding) in order to enable us to focus on patients without any ILD. Patients who had received specific PAH treatment before the right heart catheterisation (mainly bosentan for digital ulcer prevention) were excluded. Among the 145 patients initially classified as having SSc-associated PAH, we therefore excluded 60 patients, and the final study population included 85 patients. The flow chart of the study is shown in figure 1. Incident cases were defined as patients who received a diagnosis of PAH confirmed by right heart catheterisation within the year before inclusion in the registry. Date of diagnosis corresponded to date of confirmatory right heart catheterisation.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study. HRCT, high resolution computed tomography; ILD, interstitial lung disease; mPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; P(A)H, pulmonary (arterial) hypertension; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; SSc, systemic sclerosis.

Concerning SSc, baseline assessment gathered data on the cutaneous extension graded according to LeRoy's classification system and presence of anticentromere or antitopoisomerase antibodies. Modified Rodnan skin score was not systematically available and was not included in the analysis. All patients underwent pulmonary functional tests. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), total lung capacity (TLC), diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide/alveolar volume ratio (DLCO/AV or KCO) were expressed as percentages of the predicted values. Concerning PAH, routine evaluation at baseline included New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class and non-encouraged six-min walk test (6MWT), which was performed in accordance with American Thoracic Society recommendations.23 A right heart catheterisation was performed in each patient using a standard protocol. Haemodynamic measurements also included stroke volume index (SV), pulmonary artery capacitance (ratio SV/pulmonary artery pulse pressure (PP)) and right ventricle stroke work index (RVSWI) as previously described.3

No mandatory specific treatment algorithm was employed. The use of specific therapies including prostacyclin derivatives, endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs) and phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors was at the discretion of treating clinicians at each centre, according to current guidelines,24 and the availability of these agents in France.

Survival analysis

Categorical data were described by frequency and percentages; continuous data were summarised by their mean and SD (ie, mean±SD). Comparisons between two groups were performed using a Student t test or Wilcoxon's test for continuous variables and χ2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. No patient was lost to follow-up. All-cause mortality was used for analyses because causes of death could not always be confidently ascribed. One-, two- and three-year survival were assessed; date of diagnostic catheterisation was considered the baseline from which survival was measured. Individual analyses based on the Cox PH model were used to examine relationships between survival and selected variables measured at diagnosis. Events were right-censored at 36 months of follow-up. Stepwise-forward multivariable Cox PH analysis was used to examine the independent effect on survival of selected variables (those with p≤0.20 from individual analysis), controlling for possible confounders. For patients who did not have six-min walking distance (6MWD) evaluated at diagnosis because of the severity of PAH, a value of 0 was imputed when the prognostic effect of distances walked was under investigation. The two-sided significance level was set at 5%. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (V.9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Study population

In total, 85 consecutive adult patients with SSc-PAH were prospectively enrolled and constituted the study population. All patients had newly diagnosed PAH, mean duration between the first right heart catheterisation, and the inclusion in the registry was 0.2±0.22 years (range: 0.01–1.00). Characteristics of patients are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 85 incident SSc-PAH patients enrolled in the French PAH registry between 2006 and 2009

| Parameter | N | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Female gender | 85 | 70 (82) |

| Age, years | 85 | 64.9±12.2 |

| Ever/never smoker | 85 | 30 (35)/55 (65) |

| Disease characteristics | ||

| Limited/diffuse cutaneous SSc | 85 | 74 (87)/11 (13) |

| Antinuclear antibodies | 83 | 54 (65) |

| ACA positive | 83 | 33 (40) |

| ATA positive | 83 | 3 (4) |

| Functional capacity | ||

| NYHA FC, I/II/III/IV | 82 | 0 (0)/17 (21)/55 (67)/10 (12) |

| 6MWD, m | 75 | 259±126 |

| Echocardiography | ||

| Pericardial effusion present | 55 | 14 (25) |

| Pulmonary function tests | ||

| FVC, % predicted | 73 | 92±21 |

| TLC, % predicted | 73 | 94±15 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 72 | 90±22 |

| KCO, % predicted | 64 | 53±20 |

| Blood gases | ||

| PaO2, mm Hg | 57 | 70±18 |

| PaCO2, mm Hg | 54 | 33±9 |

| SaO2, % | ||

| Before 6MWT | 64 | 95±3 |

| Post 6MWT | 60 | 88±5 |

| Blood analysis | ||

| BNP, ng/l | 48 | 463±573 |

| Haemodynamics | ||

| RAP, mm Hg | 84 | 7±5 |

| mPAP, mm Hg | 85 | 41±11 |

| PCWP, mm Hg | 85 | 8±4 |

| Cardiac output, l/min | 85 | 4.44±1.56 |

| Cardiac index, l/min/m2 | 83 | 2.64±0.78 |

| PVR, dyn/sec/cm−5 | 85 | 680±355 |

| SV, ml | 71 | 57±26 |

| SV/PP, ml/mm Hg | 70 | 1.81±1.59 |

| RVSWI, g.m/m2 | 68 | 14.81±5.22 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 71 | 83±15 |

Data are mean±SD or n (%).

6MWD/T, six-min walking distance/test; ACA, anticentromere antibody; ATA, antitopoisomerase I antibody; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; KCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide corrected for alveolar volume; mPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; NYHA FC, New York Heart Association functional class; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PaO2/PaCO2 partial pressure of oxygen/carbon dioxide in arterial blood; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricle stroke work index; SaO2, oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry; SSc, systemic sclerosis; SV, stroke volume; SV/PP, pulmonary artery capacitance; TLC, total lung capacity.

Most patients had a limited cutaneous SSc (87%), and a minority had antitopoisomerase antibodies (3%). A majority of patients were in NYHA functional class III or IV (79%). Haemodynamics showed moderate to severe PAH with an mPAP of 41±11 mm Hg and cardiac index of 2.64±0.78 l/min/m2.

First-line specific therapies for PH

Fifty-nine patients were treated by first-line ERA monotherapy (bosentan (n=57), sitaxentan (n=1), ambrisentan (n=1)), 14 patients first-line with the phosphodiesterase type-5 (PDE5) inhibitor sildenafil, four patients with first-line combination of bosentan and sildenafil, and one patient with first-line epoprostenol. Five patients were not treated with a specific PAH drug during the follow-up, and data were missing for two patients. During the follow-up, 26 patients received a combination of ERA and PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil. Concerning the prostacyclin therapy, seven patients were treated with epoprostenol, two with subcutaneous treprostinil and nine with inhaled iloprost during the follow-up. Thirty-eight patients continued to receive monotherapy during the follow-up.

Survival and predictors of mortality

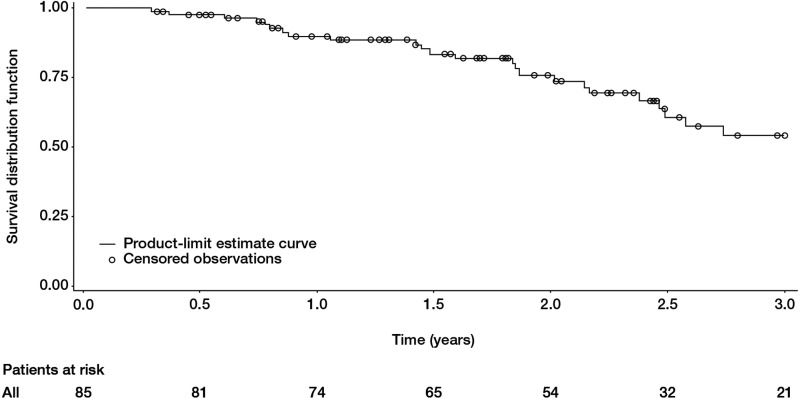

The mean duration of follow-up after PAH diagnosis was 2.33±1.09 years (median: 2.32 years). Twenty-nine patients died. Overall survival was 90% (95% CI 81% to 95%), 78% (95% CI 67% to 86%) and 56% (95% CI 42% to 68%) at 1, 2 and 3 years from PAH diagnosis, respectively (figure 2). Two patients underwent double lung transplantation for PAH and were still alive at the end of follow-up (30 and 48 months, respectively). For these two patients, pathological examination of the lung found pulmonary veno-occlusive disease.

Figure 2.

Survival in incident systemic sclerosis patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Overall survival was 90% (95% CI 81% to 95%), 78% (95% CI 67% to 86%) and 56% (95% CI 42% to 68%) at 1, 2 and 3 years from PAH diagnosis, respectively.

Univariate analysis was performed using the first 3 years of follow-up and is shown in table 2. Age and cardiac index were significant predictors in the univariate analysis. We also observed strong trends for gender, SSc subtypes, NYHA functional class, %TLC, %KCO, pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), SV/PP to be significant predictors in the univariate analysis. Conversely, 6MWD, pericardial effusion, right atrial pressure (RAP), mPAP, RVSWI and brain natriuretic peptide values were not significant predictors. The study was not designed to assess specific treatment efficacy or influence on survival.

Table 2.

Prognostic value of different variables for predicting survival in incident SSc-PAH patients

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, per year | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) | 0.012 |

| Sex, female | 0.46 (0.20 to 1.05) | 0.064 |

| SSc subtypes, diffuse | 0.15 (0.02 to 1.13) | 0.066 |

| Anticentromere antibodies | 1.65 (0.80 to 3.43) | 0.177 |

| 6MWT, m | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) | 0.154 |

| NYHA FC III/IV versus I/II | 3.75 (0.89 to 15.86) | 0.072 |

| FVC, % | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.760 |

| TLC, % | 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) | 0.062 |

| KCO, % | 0.96 (0.93 to 1.00) | 0.051 |

| Pericardial effusion | 1.69 (0.51 to 5.58) | 0.392 |

| RAP, mm Hg | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.24) | 0.914 |

| mPAP, mm Hg | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.04) | 0.675 |

| PCWP, mm Hg | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.02) | 0.130 |

| Cardiac index, l/min/m2 | 0.49 (0.27 to 0.89) | 0.019 |

| PVR, dyn/sec/cm−5 | 1.00 (1.000 to 1.002) | 0.067 |

| SV, ml | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.160 |

| SV/PP, ml/mm Hg | 0.51 (0.25 to 1.02) | 0.058 |

| RVSWI, g.m/m2 | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.07) | 0.605 |

| BNP, ng/l | 1.02 (0.72 to 1.45) | 0.892 |

6MWD/T, six-min walking distance/test; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; FVC, forced vital capacity; KCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide corrected for alveolar volume; mPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; NYHA FC, New York Heart Association functional class; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricle stroke work index; SaO2, oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry; SSc, systemic sclerosis; SV, stroke volume; SV/PP, pulmonary artery capacitance; TLC, total lung capacity.

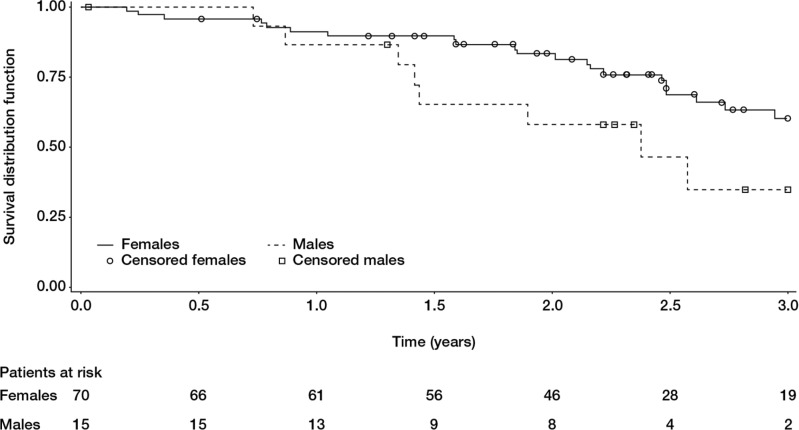

In the multivariate model including age, cardiac index, gender, SSc subtypes, NYHA functional class, %TLC, %KCO, PVR, SV/PP, we found that gender was the only independent factor associated with survival. Male gender carried a worse prognosis (HR=4.76, 95% CI 1.35 to 16.66, p=0.015; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Survival in systemic sclerosis patients with isolated pulmonary arterial hypertension and no interstitial lung disease according to gender. Male gender carries a poorer prognosis (log rank test p=0.0578).

Discussion

In this prospective study, we included SSc patients with isolated PAH without any ILD, which was newly diagnosed between 2006 and 2009, that is, in the most recent modern management era, as confirmed by the start of a specific PAH treatment in 78/83 patients with available data. Concerning the baseline characteristics, most patients (79%) were in functional class III or IV, whereas only 21% were in functional class I or II. This result was quite surprising, as guidelines and the recent literature have highlighted the importance of screening in order to capture SSc patients with less advanced PAH.16 24 25 In our recent report on incident SSc-PAH patients, we showed that 50% of SSc-PAH patients detected through systematic screening were in functional class I or II and had better haemodynamics, whereas 87% of SSc-PAH patients diagnosed during routine practice were in functional class III or IV with worse haemodynamics.16 Similarly, the mPAP, cardiac index and PVR values in the present study were closer to those of the routine practice cohort than those of the cohort detected through systematic screening in our previous study.16 Altogether, these data suggest that between 2006 and 2009, most French SSc-PAH patients were diagnosed during routine practice and not through a systematic screening, leading to a delay in diagnosis. This also suggests that the screening programmes should improve to be easily applicable in multicentre daily practice. The second important baseline characteristic to discuss is the mean age of 65 years at PAH diagnosis. When compared with other studies on SSc-PAH, our patients are older by 3–6 years, and are the oldest among all the published studies except patients described by Mukerjee et al (mean age: 66 years).17 These data are probably important for correctly interpreting the results, as age could also participate in the impairment of the baseline functional class and will impact on the overall survival.

Overall survival was 90% (95% CI 81% to 95%), 78% (95% CI 67% to 86%) and 56% (95% CI 42% to 68%) at 1, 2 and 3 years from PAH diagnosis, respectively. The 1-year survival of 90% is the best reported survival in the literature, except the 100% for the SSc-PAH patients detected through a systematic screening programme and the 90% reported by Williams et al.10 16 This result is important as the baseline characteristics of our patients were severe and the patients were old with probable comorbidities. The 1-year survival rates in the other prospective multicentre studies including incident SSc patients with PAH and no significant ILD range between 75% and 82%.4 6 16 17 In those studies, patients were enrolled between 1998 and 2006 and haemodynamics were quite similar to our study. The explanations for this good 1-year survival are not known but could, in part, be that patients in the French Registry coming from expert centres both in PAH and SSc with a multidisciplinary management, were included in the most recent modern management era (only five patients did not receive any specific PAH treatment in our multicentre study), where close follow-up and reassessment after the initiation or the change of specific PAH treatment is mandatory. Finally, it must be highlighted that we focused on patients without any ILD, whereas all previous studies mixed patients without ILD and patients with ‘non-significant ILD’. As the phenotype of PH in SSc is heterogeneous and has not been fully understood, we therefore believe that it is interesting to study a homogeneous subgroup of patients, here, SSc patients with isolated PAH and no ILD at all. The 2-year survival rate is 78% in our study, which again is better than the 56–67% described in previous multicentre prospective studies.4 6 16 17 Conversely, the 3-year survival rate of 56% was as low as in previous studies (44–59%).4 6 16 17 Again, this dismal survival at 3 years is further evidence that patients were not diagnosed during a screening programme. Indeed, in our recent study, the 3-year survival in a detection cohort was much better at 81%.16 This drop in survival, leading to a bad overall prognosis, raises some issues for which we do not have the exact explanations, only hypotheses. The first hypothesis is related to the natural history of SSc-PAH after the initiation of a specific treatment. It is possible that the specific PAH treatment improves only transiently in SSc patients but does not profoundly change the overall prognosis. It is also possible that the PAH management of these SSc patients who are older than the majority of other patients with PAH, and who often have a systemic disease, especially with myocardial involvement26 27 with comorbidities, is less aggressive with no increase or combination of treatment being administered even if the patient is worsening. Whether more aggressive management would improve the overall prognosis in such cases deserves further investigation. It is interesting to note that a majority of our patients were still on monotherapy at the end of follow-up, and that only 18 patients received parenteral prostacyclins. It is also possible that combinations of treatments are not as effective in SSc patients.28 Another explanation could be the probably underestimated frequency of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease in SSc. Indeed, a recent study showed that nearly two-thirds of patients with SSc-related PAH had two or more radiological signs of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease,29 and this was associated with a worse prognosis. Finally, only two patients underwent double lung transplantation. Dealing with these issues appears of utmost important to understand why, after 1–2 years of overall rather good prognosis, the overall long-term prognosis becomes so dismal. The most severe patients, despite an optimal therapy, without obvious contraindications to lung transplantation, should be referred to a transplantation centre to be evaluated, as their long-term prognosis is no different to the prognosis of patients transplanted for other conditions like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.30

Prognostic factors of SSc-PAH have been widely studied in the literature.7 8 However, there are discrepancies for parameters like age, gender, haemodynamics and 6MWT.7 8 Again, some of these studies included prevalent patients and all mixed patients without ILD, and patients with ‘non-significant ILD’.5 9–15 In our study focusing on incident SSc-PAH patients without ILD, we found that age and cardiac index were significant predictors in the univariate analysis. We feel that these results are important as age was reported as a prognostic factor in none of the previous studies except that of Condliffe et al.4 In this latter study, patients younger than 70 years had an overall better prognosis. Our result could be explained in part by the fact that our patients were older at PAH diagnosis than the patients in other studies, and this could have directly impacted on prognosis. Interestingly, this result is similar to that observed in idiopathic PAH where older age is associated with a worse prognosis.18 19 Concerning cardiac index, there are major discrepancies in SSc as some studies found that cardiac index was a prognostic factor,3 4 31 whereas other studies found that it was not.6 9 10 14 32 33 Among the latter negative studies for cardiac index, two studies focused on patients with ILD-related PH where cardiac index was not associated at all with the overall prognosis.14 33 We feel that by selecting isolated SSc-PAH we clearly demonstrate that baseline cardiac index is a strong prognostic factor in this selected population with a pure pulmonary vascular disease. Interestingly again, cardiac index is also an important prognostic factor in idiopathic PAH.18 19 Other parameters slightly missed the statistical significance in univariate analysis: gender (p=0.064), NYHA functional class (p=0.072), PVR (p=0.067) and SV/PP (p=0.058), %KCO (p=0.051), %TLC (p=0.062) and SSc subtypes (p=0.066).

In our study, male gender tended to be associated with a worse prognosis in univariate analysis and was independently associated with a worse prognosis in multivariate analysis (figure 3). This has been reported only once in SSc-PAH,10 whereas the majority of studies did not find any significant association between gender and prognosis.7 Of note, male gender is often reported as a bad prognostic factor in SSc without PAH.34 In the French Registry, male gender is also associated with a worse prognosis in patients with idiopathic PAH in univariate and multivariate analysis, although the explanation underlying this observation is not known.18 19 It is interesting to highlight again that by selecting patients with isolated PAH we have found some common strong prognostic factors with idiopathic PAH, such as age, gender and cardiac index. NYHA functional class III/IV is quite consistently reported as a strong prognostic factor in SSc-PAH.7 This was not as clear in our study. Again, one explanation could be the older age of our patients which could have increased the functional impairment independently from the true severity of PAH.

KCO is rarely reported as a prognostic factor in SSc-PAH without a significant ILD. Only Mathai et al also found that the lower the DLCO the worse the prognosis,9 whereas other studies have not found any association. A low DLCO or KCO reflects the importance of the pulmonary vascular bed involvement. Finally, exercise tolerance as measured by the 6MWT is a strong prognostic factor in idiopathic PAH.18 19 The majority of studies, including ours, do not support the clear association of 6MWT with the prognosis of patients with SSc-PAH.7 The limitations of 6MWT in SSc are well established.35 It is highly probable that 6MWT reflects a lot of parameters which are not all directly associated with PAH, such as musculoskeletal impairment or depression.36

Our study has some limitations. As it was a multicentre investigation, HRCT was performed using different equipment between centres, and images were not read by a single radiologist. In the same way, 6MWT and right heart catheterisation were also performed by different physicians. However, all centres were members of the French Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Network, which comprises expert university pulmonary vascular centres that are familiar with these tests, and all followed standardised protocols,23 thereby limiting variability among centres.

In conclusion, we report the prognosis of a prospectively constituted cohort of newly diagnosed incident SSc-PAH without ILD in the modern era of treatment. Our patients were older than in the literature, and had severe PAH at baseline with a majority in functional class III/IV, and with impaired haemodynamics. The overall prognosis is satisfying at 1 and 2 years despite severe PAH at baseline, but the 3-year survival remains poor. Prognostic factors mainly include age, gender and right ventricular haemodynamic function which are similar to prognostic factors observed in idiopathic PAH. These results show that we have still to improve the long-term prognosis of SSc-PAH which remains poor at 3 years even in the most modern management era. Early detection of less severe patients through easily applicable screening programmes should be a priority.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of the French Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Network: Claire Dromer, Marc-Alain Billes, Jean-Benoit Thambo, François Picard, Joel Constans, Virginie Hulot (Bordeaux, France); Irène Frachon, Yannick Jobic, Patricia Brize (Brest, France); Emmanuel Bergot, Gerard Zalcman, Pascale Maragnes, Eric Saloux, Rémi Sabatier, Thérèse Lognone, Gilles Grollier, Natacha Sobolak (Caen, France); Claire Dauphin, Aimé Amonchot, Bernard Citron, Jean-René Lusson, Isabelle Delevaux, Marc Ruivard, Denis Caillaud, Henri Marson, André Labbé, Benoît Leboeuf, Aurélie Thalamy (Clermont-Ferrand, France); Claudio Rabec, Sabine Berthier, Jean-Christophe Eicher, Caroline Bonnet, Nicolas Favrolt (Dijon, France); Christophe Pison, Christel Saint Raymond, Jean-Luc Cracowski, Stéphanie Douchin, Marie Jondot (Grenoble, France); Jean-Francois Bervar, Benoit Wallaert, Pascal de Groote, Nicolas Lamblin, Pierre-Yves Hatron, Marie Fertin, François Godart, Aurélie Noullez, Amandine Verhaeghe (Lille, France); Boris Melloni, Estelle Champagne, Francois Vincent, Elisabeth Vidal, Claude Cassat, Philippe Brosset, Stéphanie Dumonteil, Sandrine Nlend (Limoges, France); Vincent Cottin, Sylvie Di Filippo, Sabrine Zeghmar (Lyon); Gilbert Habib, Sébastien Renard, Alain Fraisse, Nicolas Michel, Martine Reynaud-Gaubert, Stéphanie Boniface, Ana Nieves, Myriam Ramadour (Marseille); Arnaud Bourdin, Philippe Godard, Michel Voisin, Catherine Sportouch-Dukhan, Pierre Fesler (Montpellier, France); François Chabot, Ari Chaouat, Emmanuel Gomez, Christine Suty-Selton, François Marçon, Anne Tisserant, Anne Guillaumot, Emmanuel Gomez (Nancy, France); Alain Haloun, Delphine Horeau-Langlard, Patrice Guérin, Annick Joly, Régine Valéro, Megguy Morisset (Nantes, France); Pierre Cerboni, Emile Ferrari, Sylvie Leroy, Fernand Macone (Nice, France); Xavier Jais, Azzedine Yaici, Olivier Sanchez, Laurence Isern (Paris, France); Pascal Roblot, Michèle-Laure Adoun, Jean-Claude Meurice, Anne-Claire Simon (Poitiers, France); Roland Jaussaud, Pierre Morand, Sonia Baumard, François Lebargy, Damien Metz, Sophie Tassan-Mangina, Fréderic Torossian, Pierre Nazeyrollas, Patrice Morville (Reims, France); Marcel Laurent, Céline Chabanne, Jean-Marc Schleich, Philippe Delaval, Patrice Jego (Rennes, France); Fabrice Bauer, Catherine Viacroze, Charlotte Vallet (Rouen, France); Matthieu Canuet, Romain Kessler, Anne-Laure Goin, Annie Trinh, Bernard de Geeter, Irina Enache (Strasbourg, France); Laurent Tetu, Gregoire Prevost, Alain Didier, Nathalie Souletie, Daniel Adoue, Philippe Acar, Yves Dulac, Joëlle Pauly (Toulouse, France); Pascal Magro, Patrice Diot, Alain Chantepie (Tours, France); Jocelyn Inamo (Fort-de-France, France); Patrice Poubeau (Saint-Pierre, France). Editorial assistance in formatting this manuscript for submission was provided by Elements Communications Limited (Westerham, UK), and funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Limited (Allschwil, Switzerland).

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The article is now unlocked.

Contributors: DL declares that he participated in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version. He had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. OS declares that he participated in the collection of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version. EH declares that he participated in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version. LM declares that he participated in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version. VG declares that she participated in critical review of the manuscript; and that she has seen and approved the final version. LR declares that she participated in the collection of data and critical review of the manuscript; and that she has seen and approved the final version. PC declares that he participated in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version. J-FC declares that he participated in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version. P-YH declares that he participated in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version. GS declares that he participated in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version. MH declares that he participated in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and that he has seen and approved the final version.

Funding: This is an academic registry and was supported in part by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd., which funded statistical analysis and editorial assistance.

Competing interests: DL has served as a consultant for Actelion, GSK and Pfizer; as a speaker for Actelion; and, has received payment for manuscript preparation from Lifesciences. OS has served as a board member for Actelion, GSK, Lilly, Pfizer and United Therapeutics and as a consultant and speaker for Actelion, GSK, Lilly and Pfizer. He has received payment for development of educational materials from Actelion. His institution has received grant funding from Actelion, Bayer Health Care, GSK, Lilly and Pfizer. His institution received grant funding from Actelion relating to the submitted work. EH has received grant funding and travel expenses from Actelion, GSK and Pfizer. He has served as a consultant for Actelion, GSK and Pfizer. LM has served as a board member, consultant and speaker for Actelion France, for which his institution received funding. His institution has received funding for travel from Actelion France and grant funding from Actelion France and Pfizer. VG is an employee of, and owner of stock/stock options in, Actelion Pharmaceuticals France. PC has served as a consultant for Abbott, Actelion, Almirall, Bayer Pharma, Cousin Biotech, Daiichi Sankyo, Genévrier, Genfit, Menarini, Mölnlycke Health Care, Pfizer, SMB and Takeda. PC has received payment for manuscript preparation from Octapharma and Lifescience. He received consultancy fees from Actelion relating to statistical analysis of the submitted work. J-FC has provided consultancy to Actelion, GSK, Lilly and Pfizer. J-FC has served as a speaker for, has developed educational materials for, and received funding for travel from Idea. GS has provided consultancy to Actelion, GSK, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and United Therapeutics. He has received grant funding, payment for speaking and payment for development of educational materials from Actelion, GSK, Lilly, and Pfizer. GS has received honorarium, support for travelling and fees for participation in review activities from Actelion in relation to the submitted work. GS institution has received grant funding from Actelion in relation to the submitted work. MH has served as a consultant for Actelion, Aires, Bayer Schering, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer and United Therapeutics and as a speaker for Actelion, Bayer Schering, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer and United Therapeutics.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Le Pavec J, Humbert M, Mouthon L, et al. Systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:1285–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:940–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campo A, Mathai SC, Le Pavec J, et al. Hemodynamic predictors of survival in scleroderma-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:252–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Peacock AJ, et al. Connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern treatment era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:151–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher MR, Mathai SC, Champion HC, et al. Clinical differences between idiopathic and scleroderma-related pulmonary hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3043–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Launay D, Sitbon O, Le Pavec J, et al. Long-term outcome of systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension treated with bosentan as first-line monotherapy followed or not by the addition of prostanoids or sildenafil. Rheumatology 2010;49:490–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson SR, Granton JT. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur Respir Rev 2011;20:277–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson SR, Swiston JR, Granton JT. Prognostic factors for survival in scleroderma associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1584–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathai SC, Hummers LK, Champion HC, et al. Survival in pulmonary hypertension associated with the scleroderma spectrum of diseases: impact of interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:569–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams MH, Handler CE, Akram R, et al. Role of N-terminal brain natriuretic peptide (N-TproBNP) in scleroderma-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1485–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawut SM, Taichman DB, Archer-Chicko CL, et al. Hemodynamics and survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension related to systemic sclerosis. Chest 2003;123:344–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stupi AM, Steen VD, Owens GR, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in the CREST syndrome variant of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:515–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girgis RE, Mathai SC, Krishnan JA, et al. Long-term outcome of bosentan treatment in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with the scleroderma spectrum of diseases. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:1626–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Launay D, Humbert M, Berezne A, et al. Clinical characteristics and survival in systemic sclerosis-related pulmonary hypertension associated with interstitial lung disease. Chest 2011;140:1016–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung L, Liu J, Parsons L, et al. Characterization of connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension from REVEAL: identifying systemic sclerosis as a unique phenotype. Chest 2010;138:1383–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humbert M, Yaici A, de Groote P, et al. Screening for pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis: clinical characteristics at diagnosis and long-term survival. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3522–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukerjee D, St George D, Coleiro B, et al. Prevalence and outcome in systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: application of a registry approach. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1088–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, et al. Survival in patients with idiopathic, familial, and anorexigen-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Circulation 2010;122:156–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Yaïci A, et al. Survival in incident and prevalent cohorts of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2010;36:549–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goh NS, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:1248–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23: 581–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 1988;15:202–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Task Force for Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of European Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Respiratory Society (ERS); International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009;34:1219–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hachulla E, Gressin V, Guillevin L, et al. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: a French nationwide prospective multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3792–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hachulla AL, Launay D, Gaxotte V, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional observational study of 52 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1878–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meune C, Vignaux O, Kahan A, et al. Heart involvement in systemic sclerosis: evolving concept and diagnostic methodologies. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2010;103:46–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathai SC, Girgis RE, Fisher MR, et al. Addition of sildenafil to bosentan monotherapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2007;29:469–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Günther S, Jaïs X, Maitre S, et al. Computed tomography findings of pulmonary venoocclusive disease in scleroderma patients presenting with precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2995–3005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saggar R, Khanna D, Furst DE, et al. Systemic sclerosis and bilateral lung transplantation: a single center experience. Eur Respir J 2010;36:893–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathai SC, Bueso M, Hummers LK, et al. Disproportionate elevation of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in scleroderma-related pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2010;35:95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathai SC, Sibley CT, Forfia PR, et al. Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion is a robust outcome measure in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Rheumatol 2011;38:2410–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Pavec J, Girgis RE, Lechtzin N, et al. Systemic sclerosis-related pulmonary hypertension associated with interstitial lung disease: impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension therapies. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:2456–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fransen J, Popa-Diaconu D, Hesselstrand R, et al. Clinical prediction of 5-year survival in systemic sclerosis: validation of a simple prognostic model in EUSTAR centres. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1788–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avouac J, Kowal-Bielecka O, Pittrow D, et al. Validation of the 6 min walk test according to the OMERACT filter: a systematic literature review by the EPOSS-OMERACT group. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1360–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoindre Y, Meune C, Dinh-Xuan AT, et al. Lack of specificity of the 6-minute walk test as an outcome measure for patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2009;36:1481–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]