Abstract

The structurally dynamic cytoskeleton is important in many cell functions. Large gaps still exist in our knowledge regarding what regulates cytoskeletal dynamics and what underlies the structural plasticity. Because Rho-kinase is an upstream regulator of signaling events leading to phosphorylation of many cytoskeletal proteins in many cell types, we have chosen this kinase as the focus of the present study. In detergent skinned tracheal smooth muscle preparations, we quantified the proteins eluted from the muscle cells over time and monitored the muscle's ability to respond to acetylcholine (ACh) stimulation to produce force and stiffness. In a partially skinned preparation not able to generate active force but could still stiffen upon ACh stimulation, we found that the ACh-induced stiffness was independent of calcium and myosin light chain phosphorylation. This indicates that the myosin light chain-dependent actively cycling crossbridges are not likely the source of the stiffness. The results also indicate that Rho-kinase is central to the ACh-induced stiffness, because inhibition of the kinase by H1152 (1 μM) abolished the stiffening. Furthermore, the rate of relaxation of calcium-induced stiffness in the skinned preparation was faster than that of ACh-induced stiffness, with or without calcium, suggesting that different signaling pathways lead to different means of maintenance of stiffness in the skinned preparation.

Keywords: cross-linker proteins, blebbistatin, MLCK, stress relaxation, Triton X-100

the filament network of cytoskeleton in all eukaryotic cells is essential for the intracellular organization and overall cellular structural integrity. Recent studies have revealed that the cytoskeleton is a dynamic structure playing a central role in diverse functions, such as organelle positioning and transport, maintenance of cell shape, intra- and intercellular signaling, cell division, and cell motility (8, 9, 12, 15, 16, 18, 23, 24, 34). Some recent studies on smooth muscle also demonstrated that the cytoskeleton possesses remarkable structural and functional plasticity, which may have potential implications in smooth muscle-related diseases, such as asthma and hypertension (2, 7, 11, 17, 29, 38, 40). Noncovalent interaction between proteins in a crowded intracellular environment is the primary framework under which cells display cytoskeletal malleability (5, 50). In smooth muscle, most of the structural proteins are organized into filaments: actin thin filaments, myosin thick filaments, and desmin- and vimentin-containing intermediate filaments. Mechanical properties of the cytoskeleton (e.g., stiffness) in smooth muscle are, therefore, very much dependent on the interaction between these filaments. Tensile stiffness of smooth muscle cells increases dramatically when the muscle is activated (41, 42, 51); this is largely due to attachment of myosin crossbridges to actin filaments that renders the muscle cells less deformable when subject to tensile stress. A largely unexplored possibility is the stiffening of the cytoskeletal filament network not related to myosin-actin interaction that produces active force, but may be a result of anchoring of actin filaments to cytoskeletal elements (54) or cross-linking of cytoskeletal and/or contractile filaments via cross-linker proteins that may or may not include myosin (32, 46). The present study is guided by the hypothesis that muscle stiffness can be divided into two components: one is maintained by active actomyosin interaction, such as that found during an active contraction; the other is maintained by cross-linkers that connect the cytoskeletal filaments (mainly actin and intermediate filaments). The latter can be best revealed when active force is abolished. To facilitate discussion, we further define crossbridges as connectors capable of generating active tension, whereas cross-linkers are connectors capable of maintaining tension and stiffness but incapable of generating active tension. The cross-linkers could be any of the actin or intermediate filament binding proteins, including myosin. However, for myosin to be a cross-linker, it has to satisfy the above definition, i.e., not able to generate active force. If active force is involved, it will simply be defined as a crossbridge. A myosin cross-linker may exist in the interaction between myosin and actin-bound caldesmon (46). Our laboratory's recent studies (32) have provided a rationale for the above hypothesis. We have found that, in intact airway smooth muscle in the relaxed state, there is a component of stiffness that is calcium sensitive (32). Siegman et al. (43, 44) have observed similar stiffness in other smooth muscles. By replacing normal physiological saline solution (PSS) containing 2 mM calcium with PSS containing zero calcium and 2 mM EGTA, we were able to reduce the passive muscle stiffness substantially without a change in the resting tension (32). Also, we have shown that inhibition of myosin light chain (MLC) kinase (MLCK) to totally abolish active force in smooth muscle did not diminish the calcium-sensitive passive stiffness (32). Taken together, the evidence suggests that there is a component of cytoskeletal stiffness that is independent of the interaction between actively cycling myosin crossbridges and actin filaments. Regulation of the cytoskeletal stiffness was further investigated in the present study using a partially skinned preparation of airway smooth muscle that was responsive to acetylcholine (ACh) stimulation, similar to that described by Gunst and colleagues (25, 48).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Care and the Biosafety Committee of the University of British Columbia and conformed to the guidelines set out by the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Skinned muscle preparation.

Sheep tracheas obtained from a local abattoir were kept in PSS (PSS or Krebs) solution (pH 7.4; 118 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 22.5 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, and 2 g/l dextrose) at 4°C. Smooth muscle strips (5–7 mm long, 1.5–2 mm wide, and 0.2–0.3 mm thick) were dissected from the tracheas, and aluminum foil clips were affixed on both ends of the strip for attachment to the force/length transducer (model 300C, Aurora Scientific). To ensure that the muscle preparations used in experiments were viable and generating normal amount of force, the preparations were periodically activated isometrically by electric field stimulation (EFS) (60 Hz, 15 V, and a current density sufficient to elicit maximal response from the muscle) at the in situ length and kept in 37°C Krebs solution aerated with carbogen (95% O2 and 5% CO2). The muscle strips were considered equilibrated when the isometric force reached a steady maximal value. To permeabilize the cell membrane, intact smooth muscle strips were soaked in skinning solution at room temperature (1% Triton X-100, 5 mM MgATP, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM imidazole, and sufficient KCl to ensure an ionic strength of 200 mM for the solution, pH = 7.0 at room temperature). To test whether the muscle had been skinned, skinning solution was replaced with normal Krebs solution, and the muscle was stimulated electrically; lack of response to EFS was taken as an indication that the muscle had been adequately skinned. The resulting skinned preparations were then used for force and stiffness measurements and fixed for electron microscopy (EM).

Protein loss and the duration of skinning protocols.

From preliminary results, we found that 1-h skinning using our protocol described above resulted in the loss of active force, but the muscle's responsiveness to ACh stimulation was retained. To find out what (if any) proteins were lost to the skinning solution and also if the ACh responsiveness could be maintained in more extensively skinned preparations, we conducted control experiments to quantify protein loss during 1 and 4 h of skinning.

For each group of experiments (which was repeated twice using muscle tissues from different animals, therefore n = 3), two muscle strips (after equilibration) were submerged completely in 300 μl of skinning solution containing 1% Triton X-100 at room temperature on an orbital shaker for either 1 or 4 h. Protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were added at the recommended concentrations in skinning solution to prevent protein degradation during the process. At the end of each time point, the muscle strips and the solution were separately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The soaking solution did not need further processing before gel electrophoresis. To extract protein from the frozen muscle strips, the muscle segment in between the aluminum clips was ground up at dry ice temperature and mixed with 200 μl RIPA buffer (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing the same dose of protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails as previously stated. The mixture of tissue powder and RIPA buffer was stirred at 4°C for 2 h before it was centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 13,200 rpm. The supernatant was obtained as the soluble fraction. The insoluble pellet was further dissolved in 8.5 M urea solution. One hundred microliters of urea were first added to the pellet, ultra-sonicated for a few seconds, and centrifuged at 4°C again. The supernatant was collected, and another 100 μl of 8.5 M urea were added to the pellet. It took four rounds of ultra-sonication and centrifugation to completely dissolve each pellet, yielding four samples to represent the insoluble fraction of each strip. DC protein assay (Life Sciences, Mississauga, ON) was performed on all samples, including the soaking solution (the eluted fraction), the soluble fraction, and the four fractions of the proteins in the pellet to obtain protein concentrations. For each sample, the volume that gave 10 μg of total protein was loaded onto a 4–20% gradient gel (Life Sciences) and ran at 200 V for 47 min to separate the protein bands. The gels were stained with Coomassie (Simply Blue, Life Sciences), scanned, and analyzed using LI-COR Odyssey 2.1 Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NB). Integrated intensity of each band was obtained with background subtracted. All proteins were identified on the gel with molecular weight as a guide.

We multiplied the protein concentration measured from protein assay by the total volume of each fraction [total of 6 fractions: soluble, 4 insoluble (dissolved from pellet), and soaking solution] and obtained the total protein extracted for each fraction. We then calculated a theoretical intensity for each fraction by multiplying the band intensity measured from a gel by a scaling factor, and that is the ratio of the total protein extracted in that fraction to the total protein loaded in that lane. For each particular protein, the eluted fraction (in the soaking solution) divided by the sum of all 6 fractions multiplied by 100 gave the percentage of the protein eluted.

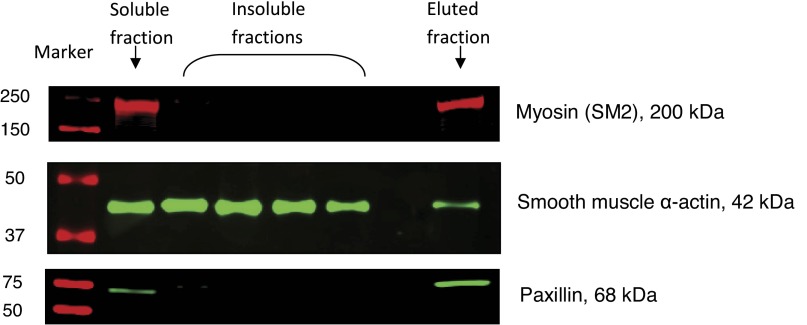

Some proteins were selected (myosin, actin, and paxillin) for further identification (confirmation) by Western analysis using antibodies for the proteins. The same protein samples and molecular weight marker that were run on the gradient gel for Coomassie stain were run on a new blank gradient gel. At the end of electrophoresis, instead of proceeding with Coomassie staining, the gel was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (pore size 0.2 μm) at 100 V for 1 h in a 4°C refrigerator. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with Tris-base saline (TBS)/5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) overnight on a shaker at 4°C. Western immunoblots were developed by incubating the membrane on a rocking platform at room temperature in sequence of a primary antibody for 1.5 h, followed by a fluorescent secondary antibody for 1 h in TBS-Tween (TBST)/5% BSA for each target of interest. The primary antibodies were as follows: rabbit polyclonal antibody against myosin isoform SM2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at 1:5,000, monoclonal mouse antibody to paxillin (BD Transduction Laboratories, Mississauga, ON) at 1:1,000, and monoclonal mouse antibody to smooth muscle α-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 1:1,000. The secondary antibodies were the goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 680 conjugated antibody (Invitrogen, Mississauga, ON) at 1:2,500 and the goat anti-mouse IRDye 800 conjugated antibody at 1:10,000. Between primary and secondary antibodies, as well as postsecondary antibody, the membrane was washed with TBST three times for 10 min each. The membrane was scanned to confirm bands of interest occurring at the expected molecular weights.

Stiffness measurement.

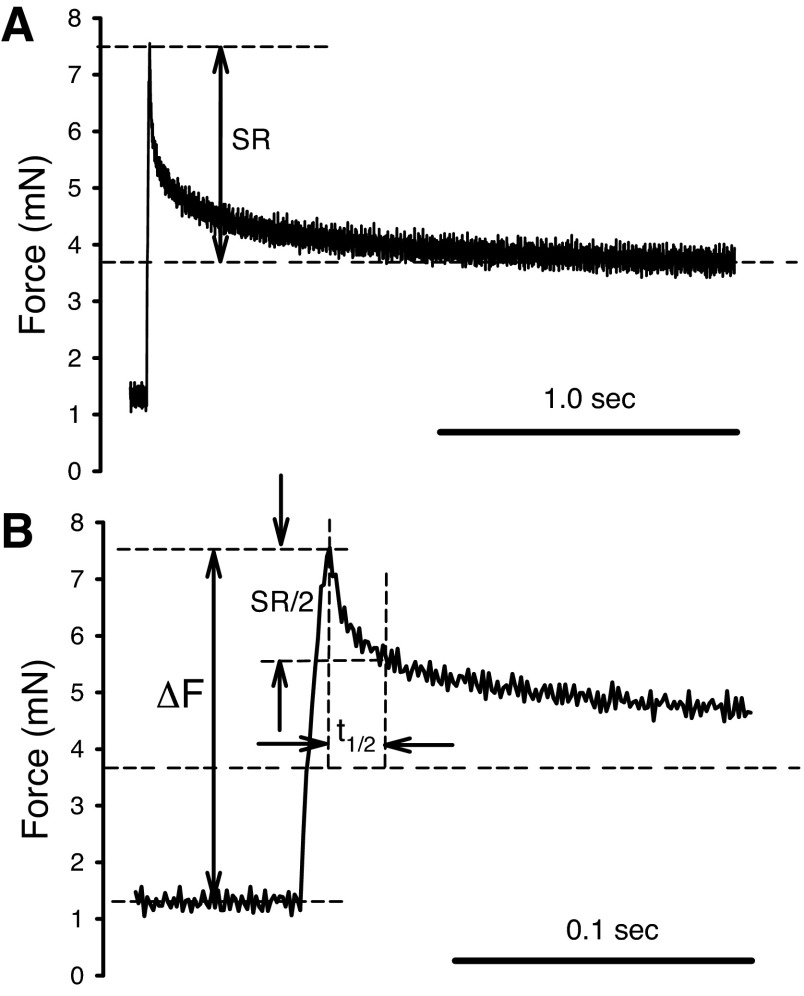

Stiffness of the smooth muscle was measured by applying a quick stretch from the muscle's in situ length. The in situ length of the muscle was used as a reference length (Lref) for normalization of all length measurements. The amplitude of the stretch was 8% Lref, and the speed of stretch was 8% Lref/0.01 s, the step-stretch was then maintained for 2 s before the muscle length was returned to Lref. An original force record is shown in Fig. 1. The peak force above the resting tension after the stretch (ΔF) divided by the step-change in length ΔL (8% Lref) was taken as a measurement of the muscle stiffness. The difference between peak-force and the force recorded at 2 s after the onset of stretch was defined as stress relaxation (SR) (see Fig. 1). We used stress instead of force because, in the analysis, the force was normalized by the muscle's cross-sectional area. The cross-sectional area of the muscle preparation was determined by measuring the width and thickness of the muscle when its length was set to Lref under a dissecting microscope. The time it took for the peak force to decline by one-half SR was defined as relaxation half-time (t1/2). Data points were recorded at a sampling rate of 1,000 Hz. The same stiffness measurement protocol and trace analysis have been described in details in one of our laboratory's recent publications (32).

Fig. 1.

Example of force trace recorded during a step-stretch in the stiffness measurement. Throughout the experiments, the amplitude (ΔL) of the step-stretch was kept at 8% reference length (Lref). A: force record during the entire step stretch (2 s). SR is the stress relaxation from the peak force to the end of recording. B: expansion of trace shown in A. ΔF is the peak force minus the baseline force. Stiffness is calculated as ΔF/ΔL. Relaxation half-time (t1/2) is the time it takes for the stress to relax from the peak force to one-half of the SR.

Experiment protocol.

After the 1-h skinning protocol, stiffness of the muscle was measured periodically at 5-min intervals. Steady-state stiffness was reached when the stiffness value was consistent for three consecutive measurements (the maximal variation from the mean value of the last three measurements was <1.5% of the mean value). The mean value was taken as the reference stiffness. This usually took 20–30 min, in addition to the 1-h skinning time. After establishing the reference stiffness, measurements of stiffness were carried out in the presence and absence of calcium and ACh.

Solutions used in the experiments were as follows: 1) relaxing, zero calcium; 2) Activating, pCa 4.5; 3) relaxing + ACh, relaxing solution with 0.1 mM ACh; 4) activating + ACh, activating solution with 0.1 mM ACh. All solutions contained 5 mM MgATP, 1 mM free Mg2+, 10 mM imidazole, 2 mM EGTA, and enough KCl to maintain 200 mM in ionic strength at pH 7.0 at room temperature.

Measurements of stiffness were done at 5-min intervals. When the cytoskeletal preparation was activated by calcium, ACh, or the combination of the two, it usually took three to four 5-min cycles for the stiffness value to reach a steady state. Similarly, when the preparation was deactivated with relaxing solution, it took several 5-min cycles for the stiffness value to return to the baseline. The reported stiffness values were all steady-state values.

Along with the described stiffness measurements above, three separate inhibitor tests were performed. The three different inhibitors used were as follows: ML-7 (1 μM), a MLCK inhibitor; H1152 (1 μM), a Rho-kinase inhibitor; (−)-blebbistatin (1 μM), an inhibitor of myosin II and also a possible disruptor of the actin cytoskeleton (53).

To compare the rate of SR of skinned muscle with that of fully activated intact muscle, intact muscle was stimulated by ACh (10−4 M), and a step-stretch was applied at the plateau of contraction. The amplitude of the stretch was 2% Lref instead of 8% Lref for skinned muscle, because we found that 8% quick-stretch during the plateau phase of contraction caused irreversible damage to the muscle. To determine whether the rate of relaxation was dependent on stretch amplitude, we performed both 8% Lref and 2% Lref stretches in the relaxed state and measured the t1/2. The rate of relaxation was found to be independent of stretch amplitude.

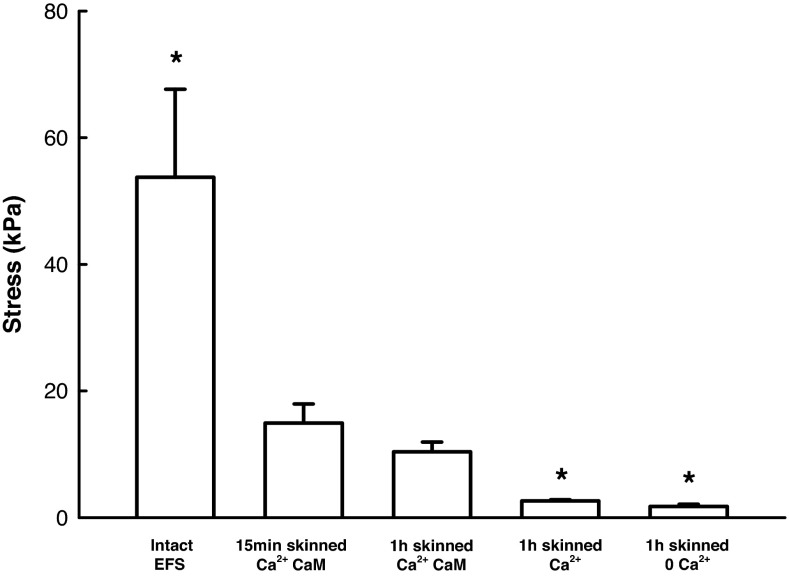

To determine the effect of exogenous free calmodulin (CaM) on force generation by the skinned preparation, 0.9 μM CaM was added to the activating solution. The skinned muscle was activated 15 min after skinning, and the tension development measured. This was followed by an additional 45-min period of incubation in the skinning solution before a second activation with activating solution supplemented with exogenous CaM (0.9 μM).

MLC phosphorylation.

Muscle strips were frozen under different experimental conditions for examination of the extent of phosphorylation of the regulatory MLC (MLC20). Prechilled acetone at dry ice temperature (−78.5°C) was used to freeze the tissue while it was still attached to the measurement apparatus. Frozen strips were quickly taken off the apparatus and placed in tubes of chilled acetone containing 5% trichloroacetic acid and 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Within 1–2 wk, the strips were processed to extract total protein. Immediately before the assay, the strips were brought to room temperature, and trichloroacetic acid was removed from the strips by two washes (30 min each) of 1 ml acetone containing 10 mM DTT. The strip was then homogenized in lysis buffer (150 μl/mg wet tissue wt) containing 6.4 M urea, 10 mM DTT, 10 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 26.4 mM Tris base, and 28.6 mM glycine. Samples were continuously inverted in a rotator at 4°C for 2 h and then centrifuged at 13,200 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was obtained immediately after and Biorad QuickStart Bradford protein assay was performed to determine the concentration of total protein in each sample. Samples were then diluted further with additional lysis buffer containing 0.02% bromophenol blue and stored at −80°C.

Phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated MLC20 was separated on 10% glycerol nondenaturing mini-gel with 3% acrylamide-urea stacking gel. Samples were thawed and loaded at equal amount of total protein in each lane. Electrophoresis was performed at 200 V for 2.5 h. Running buffer contained 100 mM glycine and 50 mM Tris. β-Mercaptoethanol was added to the inner chamber (2 μl/ml buffer). Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane at 25 V at 4°C overnight. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with TBS-5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Western immunoblots were developed in sequence: a monoclonal mouse antibody to smooth muscle MLC20 (Sigma, clone MY-21) (1:5,000) and goat antimouse IRDye 800 conjugated antibody (1:10,000) in TBST (Tween)-5% BSA. Between primary and secondary antibodies, as well as postsecondary antibody, the membranes were washed with TBST three times for 10 min each. The membrane was scanned on a LI-COR Odyssey 2.1 Infrared Imaging System, and the intensity of the bands was analyzed using software Odyssey 2.1 with background subtraction. Percent phosphorylation was determined as the ratio of the optical density of the band containing phosphorylated light chain to the sum of density of the bands containing phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated protein in the same lane.

EM.

Primary fixation (15 min) was carried out while the muscle strips were still attached to the apparatus at its Lref. The fixing solution contained the following: 1% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and 2% tannic acid in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. The fixing solution was kept at room temperature during primary fixation. After primary fixation, the muscle strip was removed from the apparatus and cut into small blocks (∼2 × ∼0.5 × ∼0.2 mm in dimension) in cold fixation buffer and kept in the same fixative for 2 h at 4°C on a shaker.

For secondary fixation, the tissue blocks were transferred to 1% osmium buffer for 1.5 h at 4°C on the shaker, followed by three washes with distilled water (10 min/wash). The tissue was stained with 1% uranyl acetate and dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol (50, 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100%) and then propylene oxide. After dehydration, small tissue pieces were embedded in resin (TAAB 812 mix). The resin blocks were sectioned with a diamond knife to obtain ultrathin sections 60 nm in thickness. The sections (on copper grids) were further stained with 1% uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Images of cross sections of the muscle cells were obtained with an electron microscope (Philips/FEI Tecnai 12 TEM) equipped with a digital camera (Gatan 792) at a magnification of ×37,000. To capture the whole cross section of a single cell, it often required taking multiple images of different parts of a cell cross section and merging the parts together by eye with the help of Adobe Photoshop.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE; n stands for the number of experiment using tracheas from different sheep. One-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test was used for all data analyses (P < 0.05 was considered significant). All statistical analyses were done using SigmaPlot 11.

RESULTS

Loss of proteins and function during skinning.

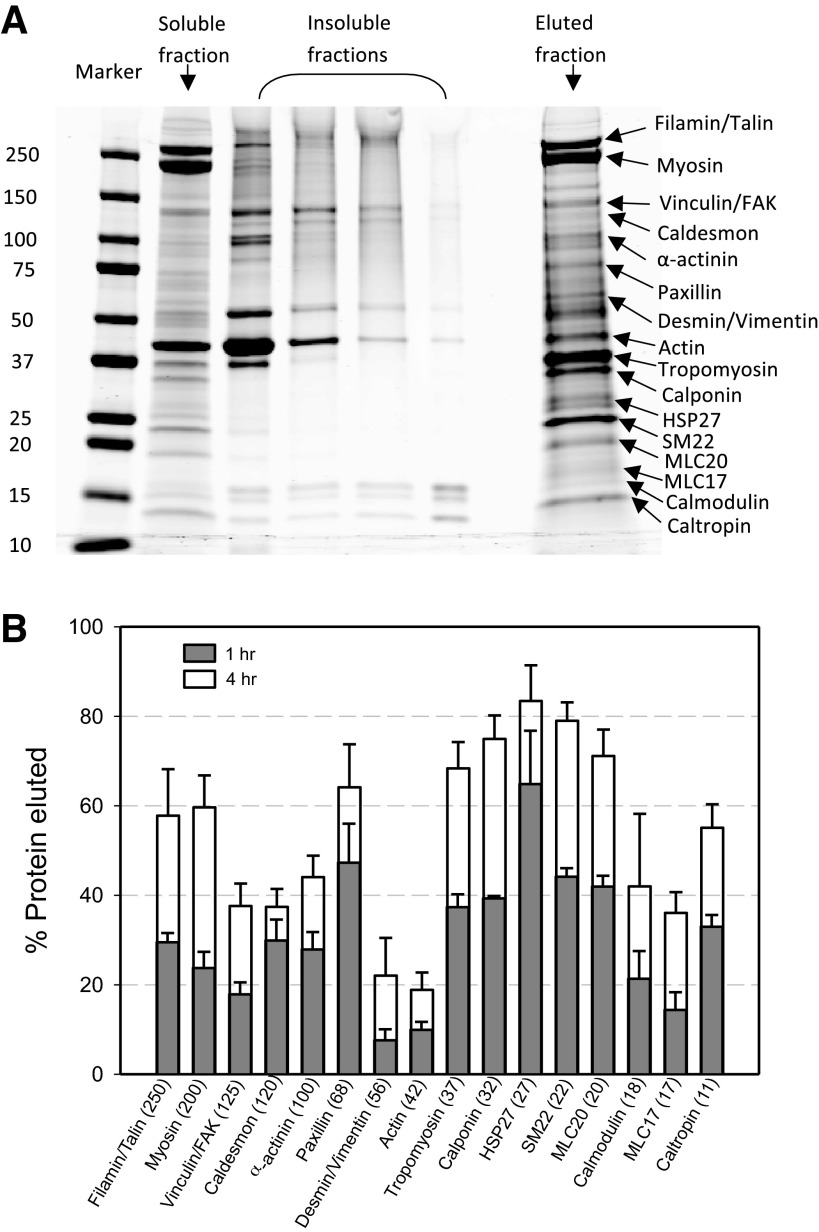

Substantial loss of intracellular proteins from the skinned preparation occurred in both 1-h and 4-h skinning protocols, with more proteins eluted from the muscle cells in longer soaking duration (Fig. 2). Identification of proteins from the gel relied on molecular weight markers. However, we did identify three proteins with immunoblotting (Fig. 3). The purpose of this group of experiments was not to identify and quantify each and every proteins eluted from the muscle preparations, but to determine whether myosin had completely eluted out of the skinned preparation (the answer was no, not even after 4 h of skinning) and to determine whether prolonged skinning could eliminate ACh responsiveness in the preparation. The answer to the second question was yes, after 4-h skinning, the preparation was no longer responsive to ACh stimulation to stiffen (results not shown). It appears therefore that 1-h skinning provides us with a window of opportunity to study ACh-induced stiffness in the absence of active force.

Fig. 2.

A: example of a SDS gradient gel stained with Coomassie. The protein samples are from a tracheal smooth muscle (SM) preparation skinned for 4 h. The “marker” lane is labeled with molecular mass in kDa. The “soluble” and “insoluble” fractions are proteins remained in the skinned muscle tissue, and the “eluted fraction” contains proteins found in the soaking solution. B: percentage of proteins eluted from skinned tracheal SM preparations quantified from gels such as the one shown in A. n = 3. See text for details for calculation of an eluted protein as a percentage of the total protein. FAK, focal adhesion kinase; MLC, myosin light chain; HSP, heat shock protein.

Fig. 3.

Immunostaining of myosin (SM2), SM α-actin, and paxillin with antibodies.

Loss of active force during the 1-h skinning protocol.

Loss of active force from the skinned muscle preparations was monitored during the process of skinning through periodic measurements of calcium-induced force in the muscle with activating solution that did not contain exogenous CaM. On average, active force appeared to reach a peak 10 min after the onset of skinning. The force then gradually decreased over time, and by 60 min no active force above the resting tension could be detected when the muscle was activated (i.e., bathed in activating solution without added CaM). When 0.9 μM CaM were included in the activating solution, the loss of active force with time was attenuated (Fig. 4), indicating that the added free CaM was important for active force generation. Because we are interested in changes in stiffness in the absence of active tension, CaM was not added to activating solution for the rest of the study.

Fig. 4.

Maximal stress generated by skinned airway SM under different conditions compared with that generated by electric field stimulation (EFS) of intact muscle at room temperature. EFS-induced stress in intact muscle was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than the calcium-induced stress produced by the muscle after 15-min incubation in the skinning solution with added exogenous calmodulin (CaM) (bar 2). Without added CaM after 1 h in the skinning solution, the muscle produced significantly (P < 0.05) less calcium-induced stress (bar 4) compared with the peak stress generated at 15 min after skinning with added CaM. Loss of stress appeared to occur between the 15-min and 1-h incubation time points (bars 2 and 3), even in the presence of added CaM, but the difference was not statistically significant. Resting stress of the skinned muscle (1 h) in the relaxed state (bar 5) was plotted here to indicate the baseline. *Significant (P < 0.05) difference from bar 2. Three muscle strips from three animals were used per condition.

Morphological change due to 1-h skinning.

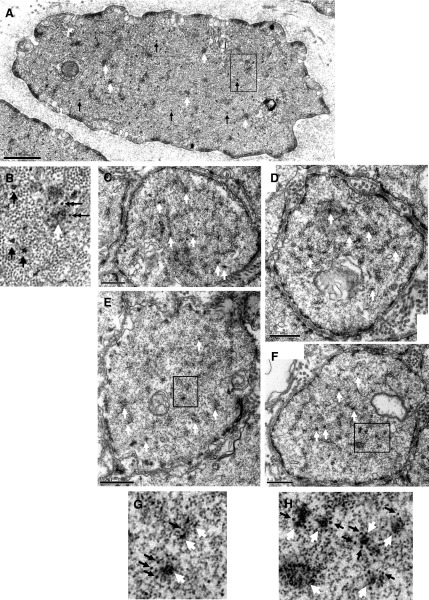

To compare the changes in ultrastructure between intact and skinned preparations, we fixed an intact muscle strip (before skinning) and used it as a reference (Fig. 5, A and B); from the same trachea we fixed a skinned strip (60 min in skinning solution) for comparison with the reference (Fig. 5, C–H). We fixed another pair of muscle strips from a different trachea to confirm that the cell morphology was qualitatively the same as those shown in Fig. 5 for intact and skinned preparations. The intact muscle (Fig. 5, A and B) showed normal intracellular features routinely observed in our laboratory's previous ultrastructural studies of intact airway smooth muscle cells (13, 21). Myosin filaments were clearly present in the intact smooth muscle cells. In contrast, the skinned muscle appeared to have no myosin filaments, even though dense bodies and intermediate filaments were present at the same abundance as in the intact muscle (Fig. 5, C–H). Note that myosin molecules could exist in nonfilamentous form as monomers or dimers and not detectable under EM. Actin filaments were also mostly preserved. Gaps in the membrane can also be seen in the skinned cells, however, a majority of the membrane appeared to be preserved. The relatively intact actin filaments and dense bodies and dense plaques in the skinned preparation suggest that the physical integrity of the cytoskeleton may be relatively intact. The presence of membrane suggests that membrane-receptor-mediated signaling pathway may also be relatively intact.

Fig. 5.

A: electron micrograph of a transverse section of an intact sheep tracheal SM cell. The muscle was fixed in the relaxed state. B: a chosen area in A (rectangle) is enlarged and shown separately. Black arrows point to some examples of myosin thick filaments; white arrows point to some dense bodies; double arrows point to some intermediate filaments. C–F: transverse sections of skinned sheep tracheal SM fixed in relaxing solution. White arrows point to some examples of dense bodies. Two sections in E and F (rectangles) are magnified and shown in G and H, respectively. White arrows indicate dense bodies, and black arrows indicate intermediate filaments. Filaments with a diameter smaller than that of intermediate filaments are actin thin filaments. No myosin thick filaments are recognizable.

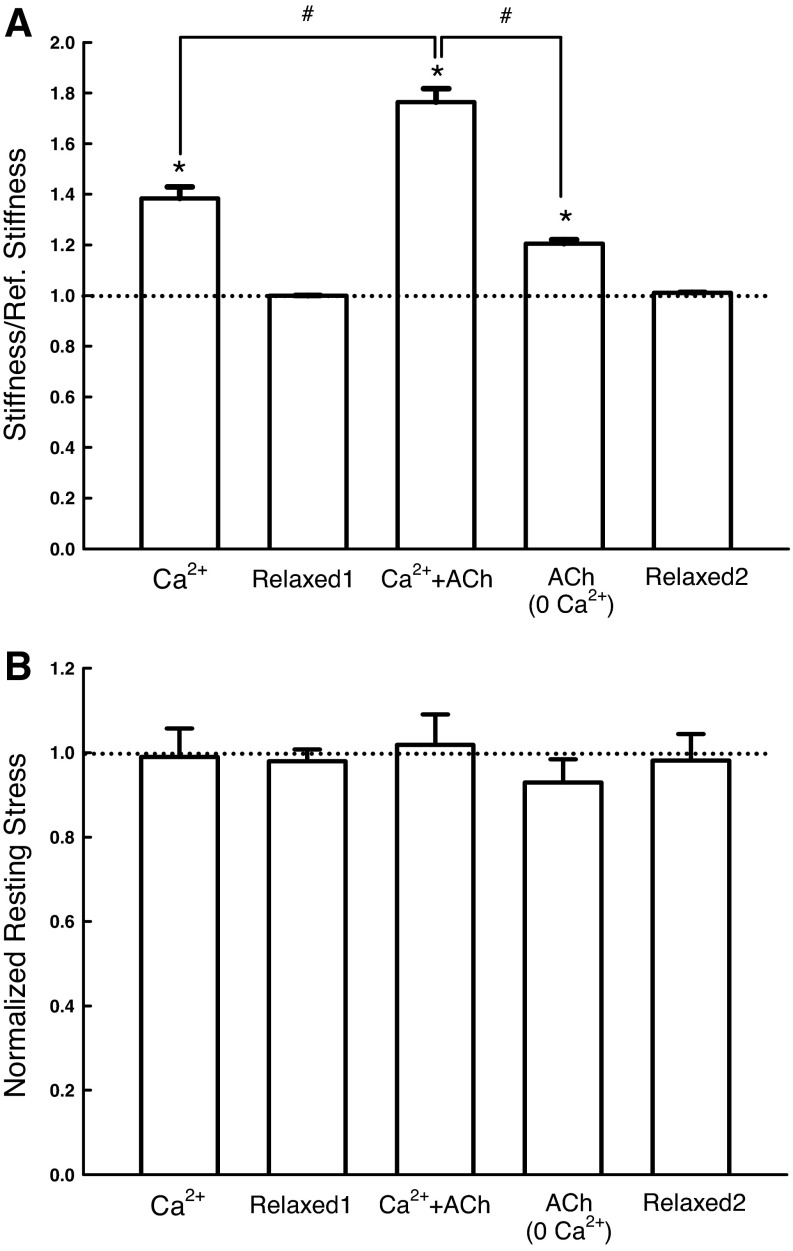

Change in stiffness due to Ca2+ and ACh stimulation.

We have thus created a relatively intact cytoskeleton lacking the ability to generate active force and without detectable myosin filaments. However, the skinning procedure did not turn the cytoskeleton into an inert tissue; the cytoskeleton responded, in terms of changes in stiffness, to direct calcium stimulation (38 ± 5% increase), ACh stimulation in the presence of calcium (76 ± 5%), and even ACh stimulation in the absence of calcium (20 ± 2%) (Fig. 6A). The changes in stiffness under the above-mentioned activation conditions were not due to active force production by the muscle. In fact, no active force was produced during activation (Fig. 6B). To confirm that the skinned muscle relaxed back to the baseline stiffness, stiffness was measured after each solution change (labeled as Relaxed1 and Relaxed2 in Fig. 6). The lack of difference among Relaxed1, Relaxed2, and the reference stiffness (dotted line) indicates that the stiffness change was reversible under the experimental conditions, and, with adequate washing with relaxing solution, stiffness always returned to baseline reference, suggesting that no irreversible structural damage occurring during the measurements. The averaged value for the reference stiffness (represented by the dotted line in Fig. 6) for this group of experiments was 32.38 ± 3.42 kPa/mm. The reference resting-stress value for this group of experiments was 3.32 ± 0.24 kPa (Fig. 6), which was ∼2% of maximal stress induced by EFS.

Fig. 6.

A: stiffness of skinned SM relative to the reference stiffness measured under different conditions: “Ca2+”, in activating solution with pCa 4.5; “Relaxed1”, in relaxing solution; “Ca2+ + ACh”, in activating solution with pCa 4.5 and 0.1 mM acetylcholine (ACh); “ACh”, in relaxing solution containing 0.1 mM ACh; “Relaxed2”, in relaxing solution again. After establishment of reference stiffness (see materials and methods), stiffness of each muscle strip was measured under each of the conditions labeled on the horizontal axis in the order from left to right (n = 5). *Significant difference (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.01) from the reference stiffness (dotted line). #Significant difference (P < 0.01) in the paired comparison. B: the corresponding resting stresses (resting tensions divided by the cross-sectional area of the muscle preparation) measured under the same conditions as in A. The resting stresses are not significantly different from one another (one-way ANOVA, P > 0.05).

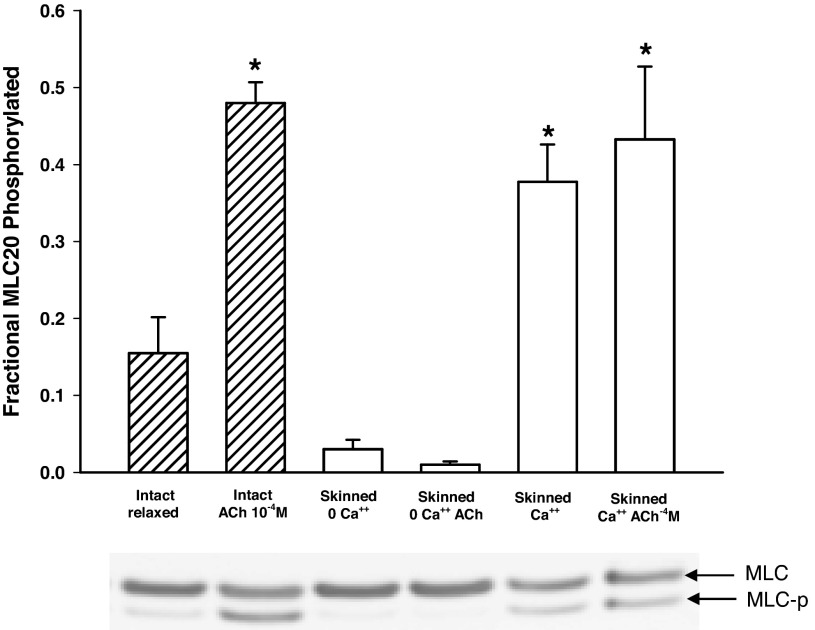

MLC phosphorylation.

Figure 7 shows results of measurements of MLC phosphorylation under various conditions. As expected, the light chain phosphorylation in intact muscle increased significantly above the basal level after stimulation. Surprisingly, significant phosphorylation was seen in skinned preparations activated with Ca2+ and Ca2+ + ACh, even though no active force was produced under these conditions (Fig. 6), another indication that myosin molecules were present in the skinned preparation, even though they might not be in filamentous form and participating in active force generation.

Fig. 7.

Phosphorylation of the regulatory MLC (MLC20) in intact and skinned muscle preparations. For the activated intact muscle (ACh 10−4 M), the muscle strips were frozen when tension development just reaches the plateau. For the skinned preparations, no CaM was added, and there was no active tension even after activation by calcium or ACh. The fractional MLC20 phosphorylated was defined as the phosphorylated (MLC-p) divided by the total MLC (MLC + MLC-p). *Significant (P < 0.05) difference from the baseline phosphorylation (intact, relaxed). The phosphorylation levels in the skinned preparations activated with Ca2+ and Ca2+ + ACh were not different from that in the intact activated muscle. Four muscle strips from four animals were used per condition.

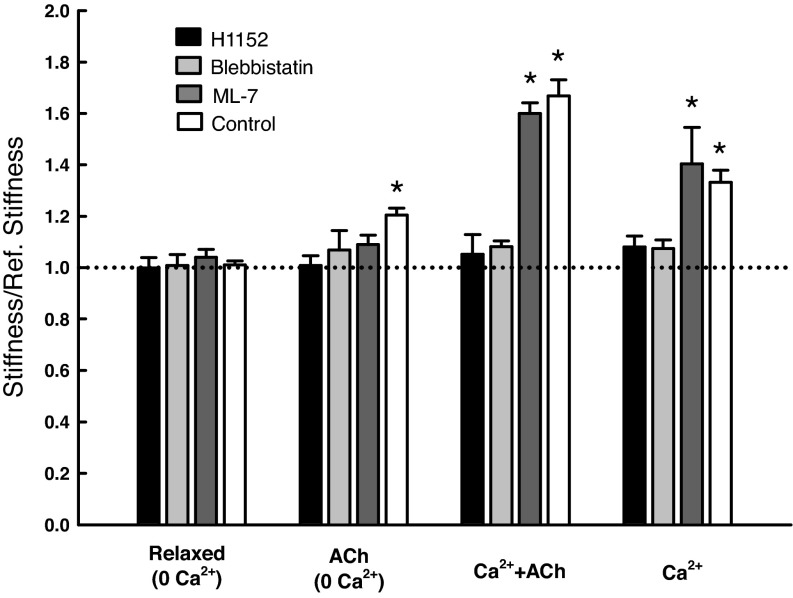

Change in stiffness in the presence of inhibitors.

To gain insights into the mechanisms regulating the cytoskeletal stiffness, we employed several inhibitors of enzymes known to be involved in the pathways of muscle activation and regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics. Using the stiffness value obtained in the relaxed state as a reference, we measured the stiffness under the same activated conditions as shown in Fig. 6 (i.e., Ca2+, Ca2+ + ACh, and ACh without Ca2+) in the presence and absence of the inhibitors. Inhibition of Rho-kinase with 1 μM of H1152 completely eliminated the stiffness increase under all three activating conditions; similarly 1 μM (−)-blebbistatin abolished the stiffness increase under all three activating conditions. Inhibition of MLCK by 1 μM ML-7 did not affect the stiffness increase due to Ca2+ or Ca2+ + ACh activation, but the stiffness induced by ACh in the absence of calcium was not different from the control (reference) (Fig. 8). The reference stiffness value for this group of experiments was 34.54 ± 2.20 kPa/mm.

Fig. 8.

Stiffness of skinned SM in the presence of inhibitors and under different activating conditions. n = 8 for the control group (without inhibitors); n = 4 for all other groups. *Significant difference (P < 0.05) from the reference stiffness (dotted line). Under the three activated conditions (ACh, Ca2+ + ACh, and Ca2+), the H1152 group differed significantly (P < 0.05) from the control group; however, the ML-7 group was not significantly different from the control group (P > 0.05). The blebbistatin group differed from the control group only under Ca2+ and Ca2+ + ACh activated conditions. Note: “Control” indicates no inhibitor.

The rate of SR.

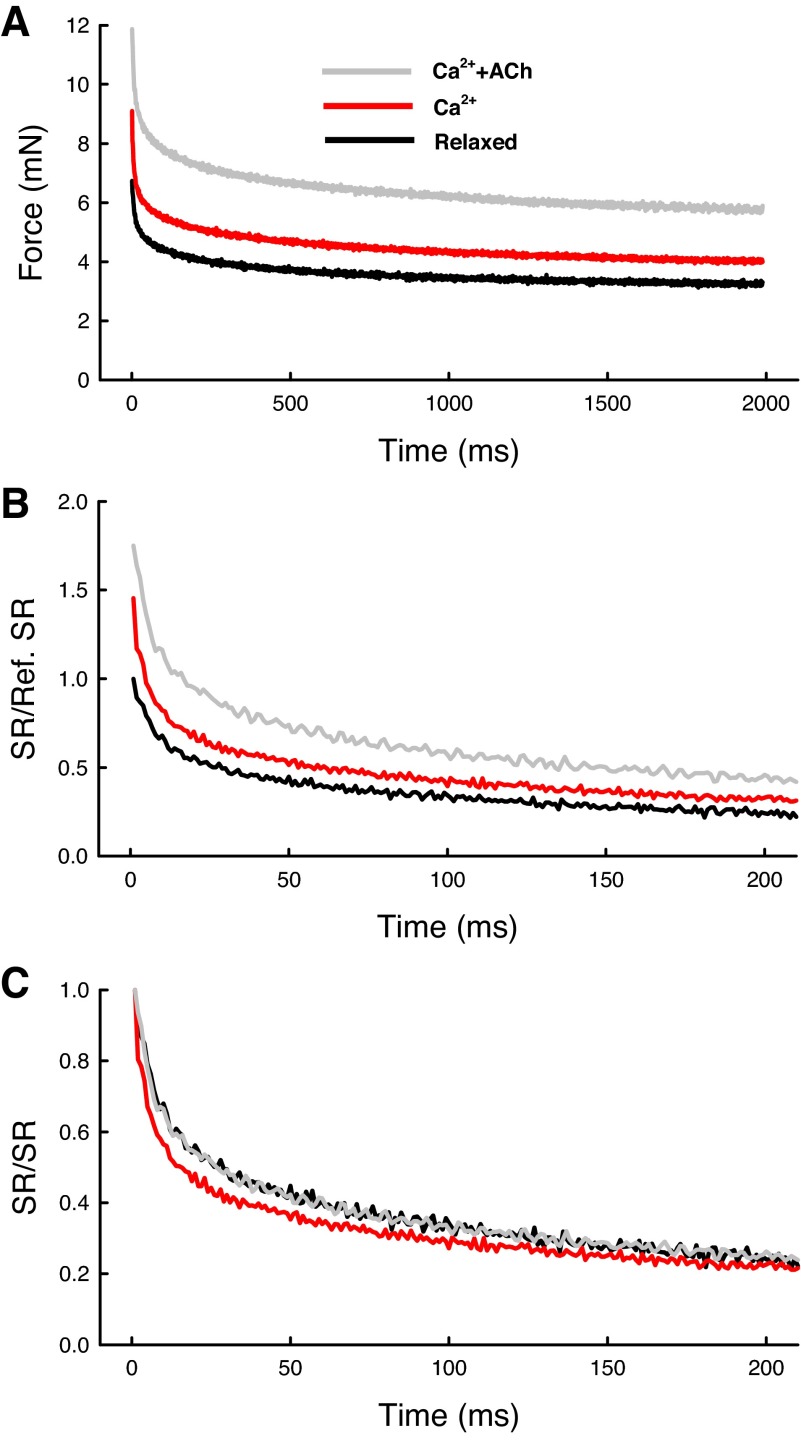

The peak stress response and the rate of SR after a step-stretch can be used to assess the structural rigidity and the rate of viscoelastic or plastic reorganization of the cytoskeleton. SR likely reflects internal structural rearrangement that involves the breaking of connections between cytoskeletal filaments and other cytoskeletal elements (such as dense bodies and dense plaques) in a time-dependent fashion. The next three figures provide more information on the time course of SR under different conditions. Figure 9A shows three averaged traces obtained in the relaxed, Ca2+-activated, and Ca2+ + ACh-activated states. The individual raw traces (n = 8 for each condition) were averaged after subtracting the baseline tension from the force records; the peak forces therefore reflected the stiffness (ΔF/ΔL) of the preparation under each of the conditions, because the amplitude of stretch (ΔL, 8% Lref) was the same for all traces. Figure 9B replots the traces from Fig. 9A with a different scale; in this plot the amount of SR was normalized by the SR obtained in the relaxed state. Figure 9C replots the traces after each trace was normalized by its own peak SR. This is to show and compare the rates of relaxation in all traces. It is clear from Fig. 9C that direct Ca2+ activation resulted in a faster rate of SR compared with the rates obtained in the relaxed and Ca2+ + ACh activated states.

Fig. 9.

Averaged traces of force recorded during step-stretches (stiffness measurements) in activated (Ca2+ + ACh and Ca2+) and relaxed states. A: averaged force (minus baseline) from peak response (ΔF) to end of a 2-s recording. B: SR normalized by reference SR. SR obtained in the relaxed state was taken as the reference. C: SR normalized by its own peak value.

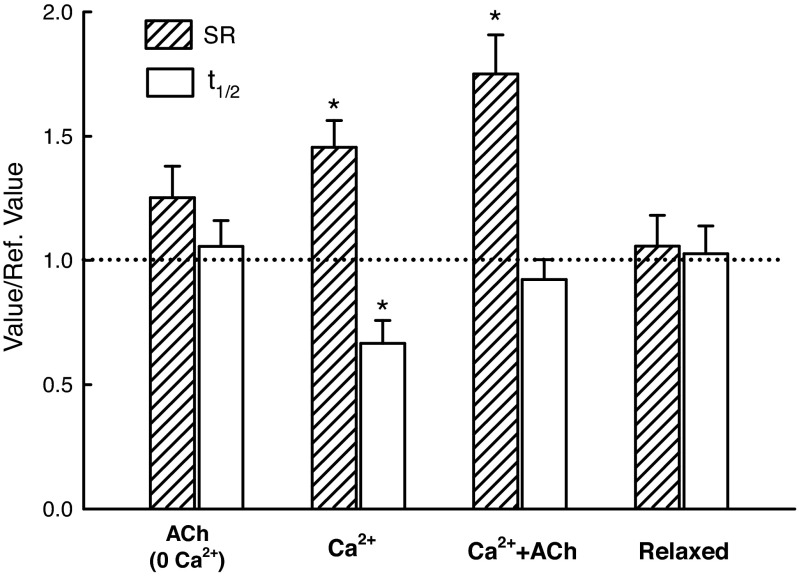

Figure 10 shows SR and the t1/2 values for all conditions normalized to their own reference values (dotted line). The reference values were obtained at the beginning of the experiments from the muscle preparations in the relaxed state. The “Relaxed” values (Fig. 10) were also obtained in the relaxed state, but in the middle and end of the experiments. The fact that they were not different from the reference values indicated that the muscle preparations were stable throughout the experiments that sometimes lasted over 8 h. The amplitude of SR was increased (P < 0.05) in the Ca2+ and Ca2+ + ACh activated states (Fig. 10), whereas the t1/2 was decreased (P < 0.05) only in the Ca2+ activated state.

Fig. 10.

Values of SR and t1/2 normalized by their respective reference values (dotted line, obtained in the relaxed state at the beginning of the measurements). The condition labeled “Relaxed” on the horizontal axis was the same as the reference condition, and the values are averages from the two groups shown in Fig. 6 (Relaxed1 and Relaxed2). *The SR values for the Ca2+ and Ca2+ + ACh activated group are different (P < 0.05) from the reference value (dotted line). *The t1/2 value for the Ca2+ activated group is different from the reference value (P < 0.05) and also different from all other t1/2 values (one-way ANOVA). Five muscle strips from five animals were used per condition.

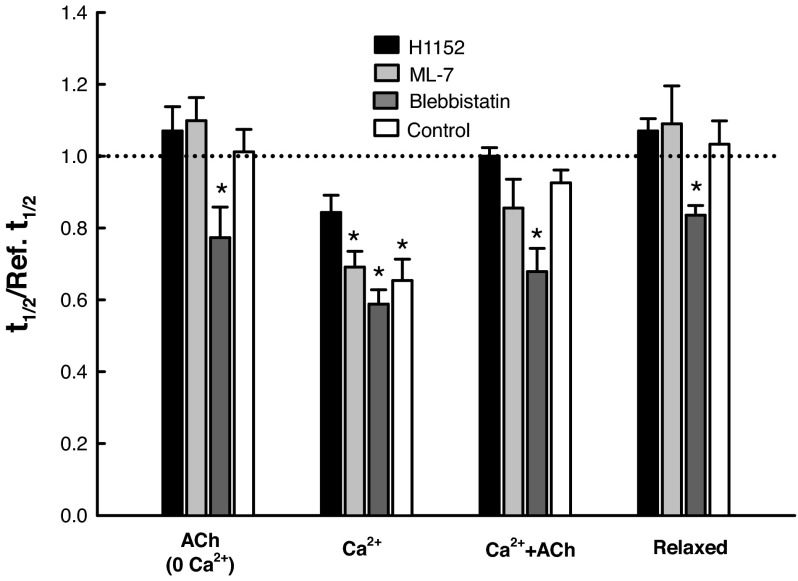

Figure 11 shows the normalized t1/2 values for all activation conditions and in the presence and absence (control) of H1152, ML-7, and blebbistatin. In the presence of ML-7, the t1/2 value varied in exactly the same fashion as the control under all activation conditions, suggesting that MLCK was not involved in the signaling pathway regulating the rate of SR. The presence of H1152 reversed the decrease in t1/2 observed under the control condition in Ca2+-activated state (Fig. 11), suggesting that the Rho-kinase was in the pathway of calcium regulation of cytoskeletal stiffness. Blebbistatin reduced the t1/2 values under all activation conditions, indicating a calcium- and ACh-independent effect.

Fig. 11.

The t1/2 values obtained under four conditions (see labels on horizontal axis) in the presence and absence (Control) of different inhibitors. *Significant difference (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05) from the reference value (dotted line). Four muscle strips from four animals were used per condition.

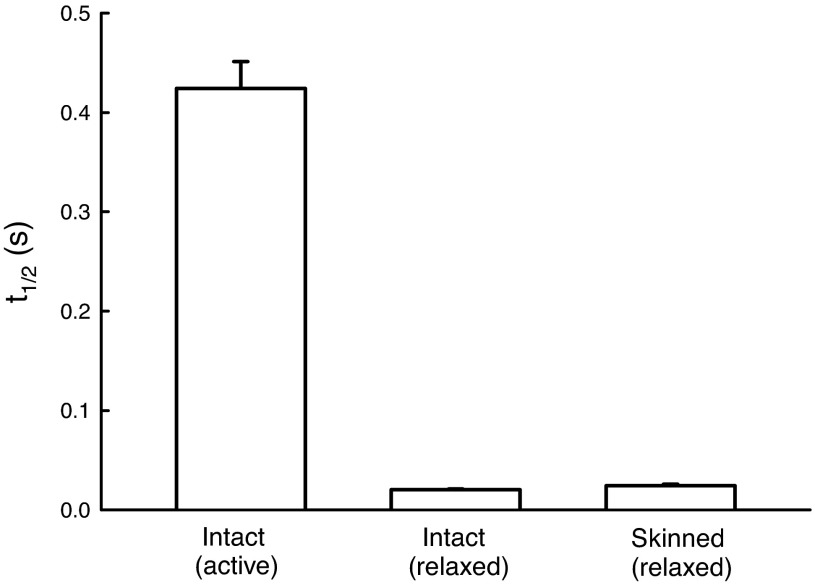

Figure 12 plots the rates of SR (measured as t1/2) during a step-stretch in intact muscle preparation in active and relaxed states, as well as in skinned preparation in the relaxed state. The stretch amplitude in activated intact muscle was 2% Lref, whereas for the muscles (both intact and skinned) in the relaxed state the stretch amplitude was 8% Lref. We used smaller stretch amplitude for the activated intact muscle because 8% Lref stretch produced irreversible damage to the muscle. To show that t1/2 was not dependent on stretch amplitude, we applied both 2% and 8% Lref stretches to intact relaxed muscle and saw no difference in the t1/2 values (data not shown).

Fig. 12.

t1/2 of intact and skinned muscle preparations. The rate of relaxation in activated intact muscle is ∼20 times slower than the rates observed in the relaxed state for both intact and skinned preparations (P < 0.001). There is no difference between the t1/2 values of intact and skinned preparations in the relaxed state. Four muscle strips from four animals were used per condition.

DISCUSSION

The ability of eukaryotic cytoskeleton to serve a variety of cellular functions depends critically on its structural dynamics. The smooth muscle cytoskeleton is a good example. For smooth muscle cells to function properly over a large length range (due to large volume change associated with hollow organ functions), drastic reorganization of the cytoskeletal structure has to occur. The mechanism underlying the process of cytoskeletal reorganization is still poorly understood, especially with respect to the unique problem of maintaining force generation and transmission within the confine of an ever-changing cytoskeleton in smooth muscle (37, 38). In intact smooth muscle, the cytoskeletal mechanics is overwhelmingly determined by the actomyosin interaction simply due to the abundant presence of myosin II and its interaction with actin filaments. Separating the contribution of active actomyosin interaction from other contributions to cytoskeletal mechanics is difficult in intact smooth muscle because the signal pathways associated with myosin activation also lead to activation of many enzymes known to be involved in the regulation of cytoskeletal reorganization (1, 30, 54). The present study is the first to attempt to remove the contribution of active actomyosin interaction in smooth muscle cytoskeletal mechanics to understand other contributing factors and mechanisms. “Passive” interaction of myosin with actin filaments cannot be excluded in this study. Here we define passive actomyosin interaction as one that does not produce active force, but is able to generate and maintain stiffness. The same definition extends to any cross-linker proteins that interact with actin and other cytoskeletal filaments; myosin crossbridges that do not produce active force in their interaction with actin filaments are, therefore, one of the possible cross-linkers.

Calcium-dependent passive stiffness has been observed in various types of smooth muscles from rabbits and guinea pigs (43, 44). In these early studies, it was found that passive stiffness was reduced by removal of calcium in the PSS, whereas passive length-tension relationship was not affected. Furthermore, it was found that passive stiffness behaved similarly in resting and rigor muscles, which led to the conclusion that most, if not all, of the crossbridges were attached in the resting muscle and were responsible for the passive resistance to stretch (4). The early studies did not explore the roles of cytoskeleton in the maintenance of passive stiffness, especially those not related to actomyosin interaction, and how the passive stiffness might be regulated.

Functional and structural changes in Triton-skinned airway smooth muscle.

Previous studies (19, 52) have shown that skinning of smooth muscle with Triton X-100 could lead to extensive loss of intracellular soluble proteins; our results (Fig. 2) are consistent with their findings. The maximal stress generated by our skinned preparation was about one-fourth of that generated by intact preparation at the same temperature (room temperature) even with exogenous CaM added. Without added CaM, no active force was produce by the muscle after 1-h skinning (Fig. 4). Because we were interested in the changes in stiffness in the absence of active force, the stiffness experiments were carried out without CaM supplementation. Comparison of intact with skinned muscle cells (Fig. 5) revealed that most of the myosin thick filaments were absent in the skinned cells, whereas dense bodies, dense plaques, actin thin filaments, and intermediate filaments were present in abundance, suggesting that the cytoskeleton may be relatively intact in our preparation. Cell membranes were mostly preserved in the skinned cells (Fig. 5), suggesting that the membrane-associated receptors could still be functional, as corroborated by the ACh response observed in the skinned preparation in the present study, as well as by other studies (25, 48) showing responsiveness of skinned preparations of airway smooth muscle to ACh stimulation. The fact that the skinned muscle could generate active force when exogenous CaM was added (Fig. 4) suggests that there are myosin in our skinned preparation.

Cytoskeletal stiffness can be separated from active force generation in smooth muscle.

The results presented in Fig. 6A indicate that, in the absence of active force, stiffness of the skinned muscle preparation can be augmented by direct calcium stimulation. Although the downstream pathways from calcium signaling were not specifically elucidated in this study, it can be argued that the pathway involving MLCK is not likely relevant in the observed calcium-sensitive stiffness because no active force was present. Abolition of active force by MLCK inhibitor in intact muscle did not reduce calcium-sensitive passive stiffness in our laboratory's previous study (32), which further suggests that MLCK and activated myosin crossbridges are not involved in the observed stiffness increase. A candidate pathway is the calcium-induced activation of Rho and Rho-kinase (30), to be discussed in more details later.

Interestingly, cytoskeletal stiffness can be augmented by ACh without calcium (Fig. 6A). This suggests that, in our skinned muscle preparation, at least some of the G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) were present, and that the associated signaling pathways were at least partially functional. Skinned airway smooth muscle preparations with similar properties have been reported previously (25, 48). The canonical pathway for GPCR signaling indicates that, although there is a cross talk with the calcium signaling pathway, activation of GPCR (by ACh) alone can lead to activation of downstream effectors that facilitate actin polymerization and filament network stabilization (30). Muscarinic (ACh) stimulation of both intact and skinned airway smooth muscle has been shown to lead to tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and focal adhesion kinase (25, 26, 48, 49), an important step involved in force transmission. Activation of the Rho family protein Cdc42 has also been shown to enhance actin filament network integrity through activation of the ARF/WASP complex (11).

Activation of the skinned preparation by calcium and ACh simultaneously revealed a greater augmentation of the muscle stiffness (Fig. 6A), and it appears that the effects of calcium and Ach are additive, suggesting that the calcium and ACh pathways act in parallel, at least as far as the cytoskeletal stiffness is concerned. Note that all the effects on the stiffness are independent of the resting tension of the muscle preparations, and also the effects were observed in the absence of active force, as shown in Fig. 6B, suggesting that the stiffness did not stem from active actomyosin interaction.

Measurements of phosphorylation of MLC20 revealed intriguing results (Fig. 7). In intact muscle at rest and at plateau of maximal contraction, the corresponding levels of phosphorylation were as expected. However, in Ca2+ and Ca2+ + ACh activated skinned muscle without supplemental CaM and active force, maximal levels of MLC20 phosphorylation were observed (Fig. 7). Our speculation is that myosin filaments are mostly depolymerized into monomers in Triton-skinned muscle strips, and some of them may have diffused out of the cells but remain trapped in the intercellular space; these myosin monomers could be phosphorylated but could not interact with actin filaments to generate force. The myosin monomers remaining in the cells may not be able to interact with actin filaments properly to generate force if they are not properly organized within the contractile units, even if they are phosphorylated. This could explain the high levels of MLC20 phosphorylation without active force in our skinned preparation. Another possible explanation is provided by the studies of Kühn et al. (20). They found a temporal difference in the manifestation of force and stiffness and MLC20 phosphorylation in skinned smooth muscle, i.e., MLC20 phosphorylation rose quickly while the increase in force and stiffness was delayed, and this delay was exaggerated when the free CaM concentration was low (0.05 μM). The uncoupling of MLC20 phosphorylation and the development of force and stiffness suggest that the phosphorylated myosin may not be responsible for the force and stiffness development when free CaM concentration is low, such as in the case of out skinned preparation.

The ACh-induced stiffness in zero calcium (Fig. 6A) occurred in the absence of MLC20 phosphorylation (Fig. 7). The stiffness is clearly independent of active force and MLC20 phosphorylation. The source of this stiffness is not clear, but cross-linking of cytoskeletal filaments by cross-linker proteins is a possibility. For myosin to be a candidate cross-linker in this case, we have to assume that ACh signaling induced a change in the affinity for actin filaments in the nonphosphorylated myosin that leads only to cross-linking but not cycling of the crossbridges.

The actin-myosin-actin connectivity described for contracting airway smooth muscle (22) is likely different from the stiffness described here for skinned muscle in the relaxed state or activated state without active force. The former is likely supported predominantly by actively cycling crossbridges in the contractile domain, whereas the latter likely stems mainly from interactions of proteins and protein filaments in the cytoskeletal domain separated from the contractile domain.

Rho-kinase is a key regulator of cytoskeletal stiffness.

To elucidate further the signaling pathways regulating the cytoskeletal stiffness, we employed some well-characterized inhibitors of enzymes known to be associated with calcium and ACh activation pathways in smooth muscle. By inhibiting Rho-kinase with H1152 (1 μM), we were able to abolish cytoskeletal stiffness induced by calcium, ACh, or a combination of the two (Fig. 8). This suggests that, at least in this particular skinned preparation, activation of Rho-kinase is critical for the regulation of the cytoskeletal stiffness. We are aware of the fact that protein loss from Triton-skinned muscle preparation is not limited to myosin (Fig. 2); caution is, therefore, necessary in applying explanations from the results obtained from skinned preparations to intact smooth muscle. It is possible that a component of cytoskeletal stiffness is Rho-kinase independent, and that this component is lost due to our skinning procedure. For example, Mehta et al. (25) found that Rho activation is not required for calcium-insensitive paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation (which presumably would enhance cytoskeletal stiffness). Base on the data obtained from our skinned preparation, we can conclude that at least a component of the cytoskeletal stiffness in smooth muscle is regulated by Rho-kinase. Loss of actin from Triton X-100 skinned smooth muscle was much less than that of myosin, as shown by Kossmann et al. (19) and the present study (Fig. 2). This may be the reason that we were able to obtain a preparation devoid of detectable myosin filaments but with a relatively intact actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 5). The fact that the stiffness obtained under the relaxed condition did not change over time during the entire time course of experiment suggests that the cytoskeletal preparations were structurally stable (Fig. 6).

Inhibition of MLCK by ML-7 (1 μM) had no effect on the cytoskeletal stiffness (Fig. 8). This is consistent with our laboratory's recent study (31) shown that, in intact smooth muscle, the passive stiffness was not affected by ML-7, even though the active force was completely abolished by the inhibitor. The results lend further support to the idea that the mechanisms responsible for active force generation and maintenance of passive stiffness in smooth muscle are not the same.

Blebbistatin reversed the increase in stiffness induced by calcium, ACh, and calcium with ACh (Fig. 8). This is expected because blebbistatin is known to inhibit myosin (33) and, as shown in taenia cecum from the guinea pig, to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton (53). Results from the blebbistatin experiments unfortunately do not allow us to distinguish the possible mechanisms underlying the stiffness reversal, either by inhibition of myosin interaction with actin, or disruption of the actin cytoskeleton, or both. If the reversal of stiffness by blebbistatin is solely due to inhibition of myosin, then ACh stimulation in the absence of calcium and MLC phosphorylation (Figs. 6 and 7) must have somehow led to cross-linking of myosin and actin (capable of maintaining stiffness but not generating tension) in a state that has never been described before. This is different from the dephosphorylated “latch bridge” (6), because the MLCs were never phosphorylated during the stimulation.

Specificity of pharmacological inhibitors is always a potential problem for studies relying on the inhibitors to elucidate signaling pathways. As mentioned above, blebbistatin could have an effect on actin cytoskeleton besides its inhibition of myosin (53). ML-7 is more specific than its parent form ML-9; however, it is able to inhibit enzymes other than MLCK. It is known to have effects on cAMP-dependent protein kinases (PKs), PKC, and calcium phosphodiesterase, although the binding affinity of ML-7 for smooth muscle MLCK is ∼100 times higher than that for the other enzymes (35). H-1152 is also more specific than its parent form HA-1077, with an IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) ∼10 times lower than HA-1077 and another Rho-kinase inhibitor Y-27632. However, H-1152 also inhibits PKA, PKC, PKG, calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, and many other enzymes, but with IC50 values at least 30 times higher than that for Rho-kinase (47). H-1152 inhibits MLCK with an IC50 value >1,000 time that for Rho-kinase (47).

Rate of relaxation after a step stretch: a window to the cytoskeletal dynamics.

Figure 9 illustrates the time course of force response due to a step-stretch. From the figure, it is clear that the increase in stiffness seen in the activated cytoskeleton (Fig. 9A) can be largely attributed to a component that relaxes rapidly after a stretch (Fig. 9B). If the SR is due to detachment of some cross-linkers or crossbridges connecting the cytoskeletal filaments in parallel, then the rate of relaxation (reflected in t1/2) would provide insights into the binding kinetics of these connectors. In the Ca2+ + ACh activated state, the binding property of the connectors appears to be the same as those in the relaxed state, and that the activation simply increases the number of the connectors. That would explain the observation that the time course of the activated trace (gray) superimposes on the control trace (black) obtained in the relaxed state (Fig. 9C). Interestingly, the Ca2+ activated trace (red) cannot be superimposed on the control trace (Fig. 9C), because the rate of SR in this activated state is faster, suggesting that the connectors detach at a faster rate. Examination of the magnitude and rate of SR under all conditions (Fig. 10) reveals that, only in activations by Ca2+ alone, were faster rates of relaxation during a step-stretch observed; this is possibly due to formation of cross-linkers or crossbridges that could be detached more easily in calcium activation compared with those formed following ACh activation. The mode of activation somehow has changed the binding properties of the connectors.

Results from Figs. 8 and 11 show that, in the presence of ML-7, the change in stiffness and the rate of SR observed in all four activation states parallels that of control. This means that the presence or absence of ML-7 makes no difference in the stiffness and the rate of SR in the skinned muscle, suggesting that MLCK is not likely part of the pathways regulating the cytoskeletal stiffness. On the other hand, inhibition of Rho-kinase by H1152 abolished stiffness increase induced by Ca2+, ACh, or the combination of the two (Fig. 8), suggesting that Rho-kinase is part of the pathways regulating the cytoskeletal stiffness.

Can we separate crossbridges from cross-linkers?

When an intact airway smooth muscle is subjected to a step-stretch at the plateau of maximal contraction, the t1/2 is ∼20 times slower than those observed in both intact and skinned muscle in the relaxed state (Fig. 12). The tension maintenance of activated intact muscle at plateau contraction is presumably sustained mostly by active myosin crossbridges; the corresponding rate of stretch relaxation observed likely reflects the rate of detachment of the crossbridges during the stretch. The large difference in the rates of SR suggests that, in the relaxed state in both intact and skinned muscles, the cell stiffness is maintained by some connectors very different from the activated crossbridges. If we define these connectors as cross-linkers, then the rate of SR could be used as a marker to differentiate crossbridges from cross-linkers. Results from Fig. 12 also suggest that none of the stiffness measured in the skinned preparation is likely originated from active crossbridges.

The effects of blebbistatin on the rate of SR appear to be nonspecific; it caused the t1/2 values to drop under all conditions, even in the relaxed condition (Fig. 11). This could be due to its effect on the cytoskeletal structures other than the cross-linkers (53), which weakens the overall cytoskeletal structure. Although blebbistatin and Rho-kinase inhibitor (H1152) appear to have the same effect on stiffness (Fig. 8), their differential effects on the rate of SR (Fig. 11) suggest that the two interventions acted on different targets.

The exact protein identity of the cross-linkers is not clear. However, it is likely that the bonds between the cross-linkers and the cytoskeletal filaments are ionic in nature. In smooth muscle cross-linking, the cytoskeletal filaments could allow maintenance of tension (developed by active actomyosin interaction) without the high energy cost associated with active cycling of the myosin crossbridges. However, the cross-linkers must be readily detachable so that they do not create too much internal load should the muscle need to shorten.

The cross-linker hypothesis is used here to facilitate discussion of results. The true origin of cytoskeletal stiffness is likely very complex and is certainly still poorly understood. A recent study suggests that poroelasticity (which results from viscous fluid flowing through an elastic filamentous matrix) could be responsible for the rapid stress response of living cells to an imposed strain and the subsequent SR (27). But as pointed by Zhou et al. (55), there is likely a diverse range of relaxation mechanisms that include changes in protein conformation and binding characteristics, colloidal glassy dynamics, in addition to poroelasticity. Some of these mechanisms may rely on pure physical interactions, but the present study suggests that at least some of them are likely strictly regulated by cell signaling, and specifically for airway smooth muscle, by the pathways that are mediated through Rho-kinase.

Physiological and pathophysiological relevance.

Mechanical properties of cytoskeleton and their regulation by intracellular signaling are areas in biology under intense investigation (8). The frequent large-scale reorganization and structurally dynamic nature of cytoskeleton reflects rapid assembly and disassembly of cytoskeletal filaments. This could be achieved more economically by binding and unbinding of protein cross-linkers with existing cytoskeletal filaments compared with de novo de-polymerization and re-polymerization of filaments. Cross-linker mechanism, therefore, could be one of the important mechanisms with which reorganization of the cytoskeleton is implemented. Because the organization of the intracellular filament network is precisely regulated, the binding property of the cross-linkers is likely precisely regulated as well. In smooth muscle, there is direct structural evidence pointing to the existence of cross-linkers (14). The protein identities of these linkers, however, are not entirely clear, and the signaling pathways regulating the binding properties of the cross-linkers are largely unknown. The calcium-sensitive actin-binding protein α-actinin may be a good candidate as a cross-linker (3); however, the specific role of the protein in the maintenance of cytoskeletal integrity is not clear. One of the few enzymes consistently identified as playing an important role in cytoskeleton dynamics is Rho-kinase (1, 10, 24, 54). One of the downstream effectors of Rho-kinase is cofilin, an actin severing protein that can be inactivated through phosphorylation by LIM kinase, which in turn is activated by Rho-kinase (36). LIM kinase activity leads to actin polymerization and filament stabilization. Activation of m-Dia and profilin by Rho-GTPase and activation of ARF/WASP by cdc42 also lead to actin polymerization and filament stabilization (11, 30). But none of the effects of these downstream effectors of Rho-kinase can be specifically linked to formation of cross-linkers of actin filaments. Phosphorylation of filamin has been shown to increase cross-linking of actin filaments (28), but the phosphorylation is mediated by tyrosine kinase, and, therefore, it may not have any relation to the Rho-kinase mediated cytoskeletal stiffness observed in this study. Phosphorylation of intermediate filaments is implicated in the formation of cross-links between microtubules and intermediate filaments (45). It is not clear whether this type of cross-links contributes significantly to cytoskeletal stiffness and whether Rho-kinase plays a role in the phosphorylation. Taken together, the existing literature does not provide a clear picture of how the dynamic structure of cytoskeleton is regulated. There is still a long way to go to define the structural mechanisms and biochemical pathways involved in the cytoskeletal dynamics. The present study used ovine tracheal smooth muscle as a model for all other smooth muscles. Caution needs to be exercised in extrapolating conclusions when comparing with other smooth muscles in the same species and from other species, although there is evidence that the cytoskeletal behavior is rather universal among many cell types from different species (50).

Physiological functions of many smooth muscle-containing organs and tissues are regulated through modulation of smooth muscle force and stiffness, both active and passive. Dysfunction of smooth muscle is implicated in many diseases and disorders (1, 17, 39). Stiffness of smooth muscle lining the wall of a hollow organ directly contributes to the distensibility of the organ. It has been found that, in severe asthma, airway distensibility is reduced (31). Blood vessel distensibility could also underlie the pathophysiology of hypertension (1, 17). Understanding the origin and regulation of cytoskeletal stiffness, therefore, could shed light on the mechanisms underlying many diseases.

Conclusion.

An increase in stiffness due to ACh stimulation was observed in a skinned airway smooth muscle preparation in the absence of calcium, active force, and MLC20 phosphorylation. Addition of calcium augmented the ACh-induced stiffness increase. The rate of stiffness relaxation after a step increase in muscle length was different in direct calcium stimulation compared with that in ACh stimulation, suggesting that the cross bridges or cross-linkers responsible for the stiffness possess different mechanical properties with different modes of activation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by operating grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (MOP-13271, MOP-37924), Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, National Science Foundation of China (Grant 11172340), and Chongqing National Science Foundation (Project no. CSTC, 2010BA5001).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: B.L., L.W., P.D.P., L.D., and C.Y.S. conception and design of research; B.L., J.Z., and D.S. performed experiments; B.L., P.D.P., L.D., and C.Y.S. analyzed data; B.L., L.W., J.Z., C.D.P., B.A.N., J.C.-Y.L., D.S., P.D.P., L.D., and C.Y.S. interpreted results of experiments; B.L. and C.Y.S. prepared figures; B.L. and C.Y.S. drafted manuscript; B.L., L.W., J.Z., C.D.P., B.A.N., J.C.-Y.L., P.D.P., L.D., and C.Y.S. edited and revised manuscript; B.L., L.W., J.Z., C.D.P., B.A.N., J.C.-Y.L., D.S., P.D.P., L.D., and C.Y.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Meadow Valley Meats Limited (Pitt Meadows, BC) for the supply of fresh sheep tracheas in kind support for this research project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano M, Nakayama M, Kaibuchi K. Rho-kinase/ROCK: a key regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 67: 545–554, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An SS, Bai TR, Bates JH, Black JL, Brown RH, Brusasco V, Chitano P, Deng L, Dowell M, Eidelman DH, Fabry B, Fairbank NJ, Ford LE, Fredberg JJ, Gerthoffer WT, Gilbert SH, Gosens R, Gunst SJ, Halayko AJ, Ingram RH, Irvin CG, James AL, Janssen LJ, King GG, Knight DA, Lauzon AM, Lakser OJ, Ludwig MS, Lutchen KR, Maksym GN, Martin JG, Mauad T, McParland BE, Mijailovich SM, Mitchell HW, Mitchell RW, Mitzner W, Murphy TM, Paré PD, Pellegrino R, Sanderson MJ, Schellenberg RR, Seow CY, Silveira PS, Smith PG, Solway J, Stephens NL, Sterk PJ, Stewart AG, Tang DD, Tepper RS, Tran T, Wang L. Airway smooth muscle dynamics: a common pathway of airway obstruction in asthma. Eur Respir J 29: 834–860, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burridge K, Feramisco JR. Non-muscle alpha actinins are calcium-sensitive actin-binding proteins. Nature 294: 565–567, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler TM, Siegman MJ, Davies RE. Rigor and resistance to stretch in vertebrate smooth muscle. Am J Physiol 231: 1509–1514, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng L, Trepat X, Butler JP, Millet E, Morgan KG, Weitz DA, Fredberg JJ. Fast and slow dynamics of the cytoskeleton. Nat Mater 5: 636–640, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillon PF, Aksoy MO, Driska SP, Murphy RA. Myosin phosphorylation and the cross-bridge cycle in arterial smooth muscle. Science 211: 495–497, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doeing DC, Solway J. Airway smooth muscle in the pathophysiology and treatment of asthma. J Appl Physiol 114: 834–843, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher DA, Mullins RD. Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature 463: 485–492, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix–cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 793–805, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerthoffer WT. Actin cytoskeletal dynamics in smooth muscle contraction. Can J Physiol Pharmarcol 83: 851–856, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunst SJ, Zhang W. Actin cytoskeletal dynamics in smooth muscle: a new paradigm for the regulation of smooth muscle contraction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C576–C587, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heng YW, Koh CG. Actin cytoskeleton dynamics and the cell division cycle. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42: 1622–1633, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrera AM, McParland BE, Bienkowska A, Tait R, Paré PD, Seow CY. “Sarcomeres” of smooth muscle: functional characteristics and ultrastructural evidence. J Cell Sci 118: 2381–2392, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodgkinson JL, Newman TM, Marston SB, Severs NJ. The structure of the contractile apparatus in ultrarapidly frozen smooth muscle: freeze-fracture, deep-etch, and freeze-substitution studies. J Struct Biol 114: 93–104, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janmey PA. The cytoskeleton and cell signaling: component localization and mechanical coupling. Physiol Rev 78: 763–781, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaqaman K, Grinstein S. Regulation from within: the cytoskeleton in transmembrane signaling. Trends Cell Biol 22: 515–526, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim h, Appel S, Vetterkind S, Gangopadhyay SS, Morgan KG. Smooth muscle signalling pathways in health and disease. J Cell Mol Med 12: 2165–2180, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, Coulombe PA. Emerging role for the cytoskeleton as an organizer and regulator of translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 75–81, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kossmann T, Fürst D, Small JV. Structural and biochemical analysis of skinned smooth muscle preparations. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 8: 135–144, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kühn H, Tewes A, Gagelmann M, Güth K, Arner A, Rüegg JC. Temporal relationship between force, ATPase activity, and myosin phosphorylation during a contraction/relaxation cycle in a skinned smooth muscle. Pflügers Arch 416: 512–518, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo KH, Seow CY. Contractile filament architecture and force transmission in swine airway smooth muscle. J Cell Sci 117: 1503–1511, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavoie TL, Dowell ML, Lakser OJ, Gerthoffer WT, Fredberg JJ, Seow CY, Mitchell RW, Solway J. Disrupting actin-myosin-actin connectivity in airway smooth muscle as a treatment for asthma? Proc Am Thorac Soc 6: 295–300, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehman W, Morgan KG. Structure and dynamics of the actin-based smooth muscle contractile and cytoskeletal apparatus. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 33: 461–469, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung T, Chen XQ, Manser E, Lim L. The p160 RhoA-binding kinase ROK alpha is a member of a kinase family and is involved in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton. Mol Cell Biol 16: 5313–5327, 1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta D, Tang DD, Wu MF, Atkinson S, Gunst SJ. Role of Rho in Ca2+-insensitive contraction and paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C308–C318, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta D, Wang Z, Wu MF, Gunst SJ. Relationship between paxillin and myosin phosphorylation during muscarinic stimulation of smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C741–C747, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moeendarbary E, Valon L, Fritzsche M, Harris AR, Moulding DA, Thrasher AJ, Stride E, Mahadevan L, Charras GT. The cytoplasm of living cells behaves as a poroelastic material. Nat Mater 12: 253–261, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pal Sharma C, Goldmann WH. Phosphorylation of actin-binding protein (ABP-280; filamin) by tyrosine kinase p56lck modulates actin filament cross-linking. Cell Biol Int 28: 935–941, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paré PD, McParland BE, Seow CY. Structural basis for exaggerated airway narrowing. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 85: 653–658, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puetz S, Lubomirov LT, Pfitzer G. Regulation of smooth muscle contraction by small GTPases. Physiology (Bethesda) 24: 342–356, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pyrgos G, Scichilone N, Togias A, Brown RH. Bronchodilation response to deep inspirations in asthma is dependent on airway distensibility and air trapping. J Appl Physiol 110: 472–479, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raqeeb A, Jiao Y, Syyong HT, Paré PD, Seow CY. Regulatable stiffness in relaxed airway smooth muscle: a target for asthma treatment? J Appl Physiol 112: 337–346, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratz PH, Speich JE. Evidence that actomyosin cross bridges contribute to “passive” tension in detrusor smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1424–F1435, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rottner K, Stradal TE. Actin dynamics and turnover in cell motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol 23: 569–578, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitoh M, Ishikawa T, Matsushima S, Naka M, Hidaka H. Selective inhibition of catalytic activity of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase. J Biol Chem 262: 7796–7801, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott RW, Olson MF. LIM kinases: function, regulation and association with human disease. J Mol Med 85: 555–568, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seow CY. Biophysics: fashionable cells. Nature 435: 1172–1173, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seow CY. Myosin filament assembly in an ever-changing myofilament lattice of smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289: C1363–C1368, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seow CY. Passive stiffness of airway smooth muscle: the next target for improving airway distensibility and treatment for asthma? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 26: 37–41, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seow CY, Fredberg JJ. Emergence of airway smooth muscle functions related to structural malleability. J Appl Physiol 110: 1130–1135, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seow CY, Stephens NL. Time dependence of series elasticity in tracheal smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol 62: 1556–1561, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seow CY, Stephens NL. Changes of tracheal smooth muscle stiffness during an isotonic contraction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 256: C341–C350, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegman MJ, Butler TM, Mooers SU, Davies RE. Crossbridge attachment, resistance to stretch, and viscoelasticity in resting mammalian smooth muscle. Science 191: 383–385, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegman MJ, Butler TM, Mooers SU, Davies RE. Calcium-dependent resistance to stretch and stress relaxation in resting smooth muscles. Am J Physiol 231: 1501–1508, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sihag RK, Inagaki M, Yamaguchi T, Shea TB, Pant HC. Role of phosphorylation on the structural dynamics and function of types III and IV intermediate filaments. Exp Cell Res 313: 2098–2109, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutherland C, Walsh MP. Phosphorylation of caldesmon prevents its interaction with smooth muscle myosin. J Biol Chem 264: 578–583, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamura M, Nakao H, Yoshizaki H, Shiratsuchi M, Shigyo H, Yamada H, Ozawa T, Totsuka J, Hidaka H. Development of specific Rho-kinase inhibitors and their clinical application. Biochim Biophys Acta 1754: 245–252, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang DD, Gunst SJ. Selected contribution: roles of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin in the mechanosensitive regulation of myosin phosphorylation in smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol 91: 1452–1459, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang D, Mehta D, Gunst SJ. Mechanosensitive tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and focal adhesion kinase in tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C250–C258, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trepat X, Deng L, An SS, Navajas D, Tschumperlin DJ, Gerthoffer WT, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature 447: 592–595, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warshaw DM, Rees DD, Fay FS. Characterization of cross-bridge elasticity and kinetics of cross-bridge cycling during force development in single smooth muscle cells. J Gen Physiol 91: 761–779, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watanabe M, Takano-Ohmuro H. Extensive skinning of cell membrane diminishes the force-inhibiting effect of okadaic acid on smooth muscle of guinea pig hepatic portal vein. Japn J Physiol 52: 141–147, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watanabe M, Yumoto M, Tanaka H, Wang HH, Katayama T, Yoshiyama S, Black J, Thatcher SE, Kohama K. Blebbistatin, a myosin II inhibitor, suppresses contraction and disrupts contractile filaments organization of skinned taenia cecum from guinea pig. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298: C1118–C1126, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang W, Huang Y, Gunst SJ. The small GTPase RhoA regulates the contraction of smooth muscle tissues by catalyzing the assembly of cytoskeletal signaling complexes at membrane adhesion sites. J Biol Chem 287: 33996–34008, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou EH, Martinez FD, Fredberg JJ. Cell rheology: mush rather than machine. Nat Mater 12: 184–185, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]