Abstract

Background:

Patient safety is a top priority of healthcare organizations. The Joint Commission (TJC) is now requiring that healthcare organizations promulgate polices to investigate and resolve disruptive behavior among employees.

Methods:

Our aims in this investigation utilizing the Provider Conflict Questionnaire (PCQ: Appendix A) included; determining what conflicts exist among a large sample of healthcare providers, how to assess the extent and frequency of disruptive behaviors, and what types of consequences result from these conflicts. The PCQ was distributed utilizing electronic postings, and predetermined e-mail lists to nurses and physicians across the US.

Results:

The convenience sample included 617 respondents to the questionnaire. All incomplete responses (failure to answer all 17 items on the questionnaire) were excluded from data analysis. Our major finding was that disruptive behavior was the greatest problem observed in 82% of organizations; 74% personally witnessed these behaviors, while 5% personally experienced these behaviors. Friedman analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyses demonstrated that the difference between these three estimates were significant (χ2 = 207.8 df = 2, P < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

Healthcare organizations in the US are bound by TJC regulations to develop leadership standards that address disruptive behavior. These organizations can no longer stand by and ignore behaviors that threaten not only the bottom line of the institution, but also most critically, patient safety. As more attention is being paid to recommendations and mandates from the TJC and the Institute of Medicine (IOM), we will need more data, like those provided from this study, to better document how to address, resolve, and prevent future “misbehaviors”.

Keywords: Disruptive behavior, healthcare organization, recommendations: Leadership standards: Patient safety

Editorial Comment

Few would deny that disruptive behaviors exist in hospital settings, and that there is a need to minimize them. However, relatively little is known about the nature and frequency of such behaviors occurring between medical care providers. This article is an attempt to better understand the problem.

Utilizing the Provider Conflict Questionnaire (PCQ), the article attempts to document the extent to which disruptive behaviors occur, and delineates to some extent, the “who, what, and where” of the problem. A major shortcoming of the study is that 88% of the 617 respondents were nurses. The findings, therefore, largely reflected their opinions and biases. However, interestingly, there were no significant differences in the rates of organizational, witnessed, and personal experiences of disruptive behaviors by gender. As the nurses were predominantly female, and the nonnurses (doctors and administrators) were predominantly male, this suggests that the results may have not been substantially different had the population included more doctors. In any case, a follow-up study should include a larger sample of doctors. This is particularly important as nurses (predominantly females and including female Physician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners) and doctors (predominantly males) agreed that physicians were most often responsible for the disruptive behaviors. This is not to say that everyone involved cannot be better behaved.

Furthermore it is easy to find shortcomings in social scientific studies of complex situations, including this one. This study was not a randomized, controlled study, and the questionnaire data were largely based upon qualitative and impressionistic responses. But scientific inquiry starts with descriptive studies, and if we are going to make progress here, we have to move from complaints in the hallway to more rigorous documentation and description.

We should, therefore, use this opportunity to improve the social environment in our hospitals, especially given that some claim that disruptive behavior negatively impacts patient care. Interestingly, it appears that the mere existence of appropriate institutional policies and procedures aimed at addressing disruptive behaviors decreased the incidence of these behaviors. Let's hope that articles like this will initiate discussions in institutions that do not have these policies, and will help improve the policies in those institutions that do.

Nancy Epstein, MD

Editor, SNI: Spine

INTRODUCTION

More attention is being paid to the quality of patient care in healthcare institutions across the country. As disruptive behaviors arising between clinicians (physicians, nurses, adjunctive personnel) negatively impact patient care, they will increasingly be recognized and addressed. However, a new culture of safety is now emerging that will enable clinicians and employees to feel empowered to report significant conflicts varying from minor disagreements to fully disruptive behaviors.[1] Errors potentially attributed to these behaviors will increasingly be recognized without adding risk to the “whistle blower.”[9]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The goals of our project included; assessing the types of conflicts among a large sample of healthcare providers, determining the extent and frequency of disruptive behaviors, and evaluating the consequences of these conflicts. The study first looked at the different perceptions of physicians vs. nurses regarding the frequency and severity of conflicts. Next, we asked whether the participants knew the policies regarding disruptive behaviors within their institutions, and how/whether this impacted their awareness of these conflicts. Finally, we determined the frequency, efficacy, and timeliness of institutional responses to disruptive behaviors.

Analysis of inter-provider conflict study

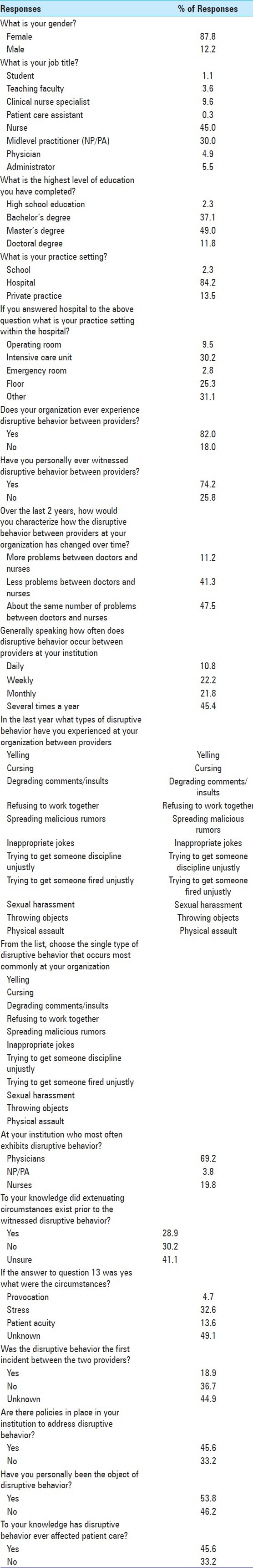

Previous analyses of inter-provider conflicts showed how providers in healthcare settings across the country perceived the extent of provider conflicts and disruptive behaviors, and the consequences of these behaviors. This information was collected utilizing voluntary/anonymous surveys. The American College of Physician Executives (ACPE) published a study in 2009; the Doctor–Nurse Behavior Survey [Table 1].[5] They were granted permission to adapt the 2009 Doctor–Nurse Behavior Study.[5] With Institutional Review Board (IRB#12439) approval, the Provider Conflict Questionnaire (PCQ) questionnaire [Table 1] was distributed via email to nursing and physician groups across the US and through a predetermined e-mail list; the survey was placed online at https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/pconflictsurvey. In addition, the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses (AANN), the editorial board of Surgical Neurology International, Spine Supplement, and the New York State Nurse Practitioner Association posted the survey on their websites. Respondents included a convenience sample of 617.

Table 1.

Summary of results

PCQ questionnaire

The PCQ and the 2009 Doctor–Nurse Behavior Survey were the surveys used for this study [Table 1]. The latter survey asked demographic questions such as gender, educational level, job title, and specific questions about behaviors among doctors and nurses at the respondents’ institutions; these questions were subsumed into the PCQ [Table 1].[5] Questions also included what types of behavior problems were observed among doctors and nurses, and how often they occurred within individual institutions. The survey further questioned whether extenuating circumstances surrounded disruptive behaviors (e.g., stress, provocation, etc.) and whether, to the respondent's knowledge, the disruptive behavior affected patient care.

Statistical evaluation

As all of the data from this survey was ordinal, nonparametric techniques were the primary statistical analysis tool. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two independent variables, and the Friedman analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare multiple independent ordinal variables. Cross tabulation tables were also created as appropriate, and analyzed for statistical significance using the χ2 test. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine whether a dependent variable was significantly affected by an independent variable.

RESULTS

Disruptive behavior reported by 82% of respondents

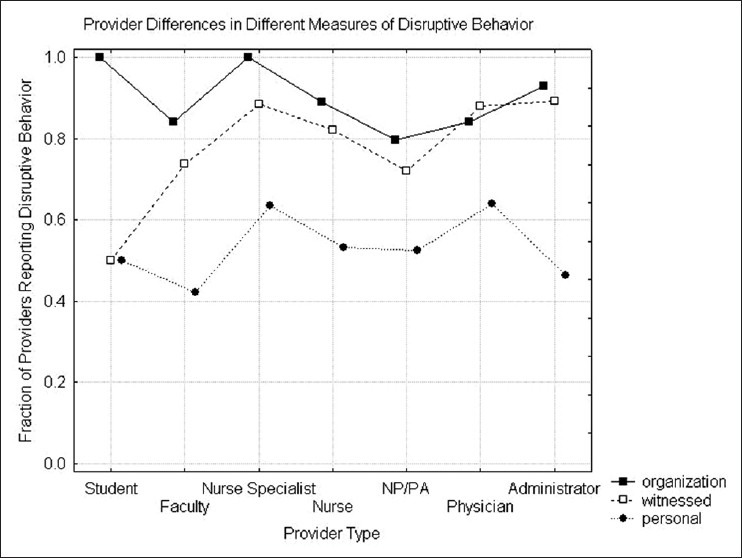

Disruptive behavior was reported by 82% of respondents at their institutions (e.g. defined as the perceived organizational rate) [Table 1 and Figure 1]. Additionally, 74% had personally witnessed disruptive behavior, while 53% were the object of such behaviors. The Friedman ANOVA analysis demonstrated that the difference between these three estimates were significant (χ2 = 207.8, df = 2, P < 0.0001). Although 41% felt that the incidence of disruptive behavior was declining, slightly more than 11% sensed a trend toward observing more disruptive behavior over time. Furthermore, 10.9% of respondents felt disruptive behavior occurred daily at their organization, 22.3% weekly, 21.7% monthly, and 45.4% a few times a year. Interestingly, different types of healthcare providers perceived the same frequencies of disruptive behavior.

Figure 1.

Provider differences in measures of disruptive behavior

Most comment types of disruptive behaviors

The most common types of disruptive behaviors included yelling, degrading comments, and refusing to work together [Table 1]. Other disruptive behaviors included: “sabotage, bullying on social media, hanging up the phone, providers not paying attention to information from the nurses, and passive aggressive behaviors.”

Gender

In this survey, in which gender was not evenly distributed over all roles (χ2 = 151.7, P < 0.001), there were no significant differences in the rates of organizational (Mann–Whitney U = 18810, P = 0.82), witnessed (U = 18950, P = 0.67), and personal experiences of disruptive behaviors (U = 12782, P = 0.66) for males (12% of the sample) vs. females (88% of the sample) [Table 1]. In fact, there were no differences in organizational, witnessed and personal experiences by gender, although most female responders were nurses ((45%), Nurse Practitioners (NP)/Physician Assistants (PA) (30%), and clinical nurse specialists (CNS) (9.8%)) and most male responders were physicians (4.9%) and administrators (5.5%). The pooled data regarding these behaviors are discussed under separate headings.

Level of education

The level of education had no statistically significant effect on the three indicators of disruptive behavior; 11.6% had a doctoral degree, 49% had a master's degree, 37% had a bachelor's degree, while only 2.3% had a high school education [Table 1].

Greatest frequency of disruptive behaviors

Disruptive behaviors were most often attributed to physicians (69%), followed by nurses (over 19%), and ultimately by NPs/PAs (3.8%) [Table 1]. Both physicians and other providers (PAs, nurses, etc.) were aware that physicians were most often associated with disruptive behaviors. Of interest, however, the perception of disruptive behaviors was not influenced by the role of the provider (Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA (H (7, N = 478)=9.86, P = 0.20).

Significant differences in perception of organizational and witnessed disruptive behavior

Although providers with different roles showed significant differences in the perception of organizational (H (7, N = 605)=35.86, P < 0.0001, df = 7) and witnessed disruptive behaviors (Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA) (H (7, N = 603)=32.91, P = 0.0001), the risk of personally experiencing disruptive behaviors H (7, N = 511), 6.41 P = 0.49 did not depend on the role of the provider. Disruptive behavior rates were highest for CNSs, followed in descending order by: physicians, NPs/PAs, and, finally, nurses (Figure 1; note that Patient Care Associates [PCAs] were eliminated as there were so few). Notably, although nurses were reportedly involved in lower levels of personal disruptive behavior compared with physicians, they experienced higher levels of witnessed and organizational disruptive behavior.

Workplace location

Eighty-four percent of the respondents to our survey worked in hospitals: 9.5% worked in the operating room (OR), 30.3% worked in the intensive care unit (ICU), 2.8% worked in the emergency room (ER), 26.4% worked on the floor, while 31% held other roles (13.8% private practices, 2.3% schools) [Table 1].

Disruptive behavior more common in hospitals

Based on an analysis of cross tabulation tables (χ2 = 15.79, df = 2, P < 0.001), disruptive behavior was more common in the hospitals (80%) than in the clinics (58%) [Table 1]. Of interest, there were significant differences in the rates of witnessed disruptive behaviors for different hospital locations (χ2 = 14.18, df = 4, P = 0.007); the highest incidence was in the ICU and ER, while less occurred in the OR and on the floor.

However, the perceived organizational rate of disruptive behavior (χ2 = 7.97, df = 4, P = 0.09) and the chance that the respondent was personally an object of disruptive behavior (χ2 = 4.72, df = 4, P = 0.31) did not depend on the in-hospital location.

Extenuating circumstances (provocative factors) lead to disruptive behavior

Respondents determined there were no extenuating circumstances leading to disruptive behaviors in 30.2% of patients, 41% were uncertain, while 28.8% attributed disruptive behaviors to extenuating circumstance (stress, patient acuity) [Table 1]. Factors contributing to the latter incidence of disruptive behavior included a 4.7% incidence of direct provocation, a 32.6% frequency of stress, and 13% likelihood of increased patient acuity. Furthermore, 18% of the latter respondents saw disruptive behavior as a de-novo event, but 38.6% felt that it had occurred on more than one occasion between the parties involved.

77% of respondents acknowledge organizational policies addressing disruptive behaviors

Although 77% of respondents were aware of policies in the organization to address disruptive behavior, 9.4% said there were no such policies, while 13.6% were uncertain. Interestingly, cross tabulation data revealed that knowing that organizational policies existed did not significantly impact the incidence of disruptive behaviors occurring either in an institution (χ2 = 2.54, df = 2, P = 0.28), or to the individual (e.g. personally witnessed disruptive behaviors) (χ2 = 2.61, df = 2, P = 0.27). Organizational behavioral policies did, however, have a small effect on whether the respondent was the personal object (χ2 = 7.35, df = 2, P = 0.026) of disruptive behavioral attacks; the rate was 52% when these policies and procedures were in place vs. 71% when there were none.

Disruptive behavior negatively impacts patient care

Respondents noted that disruptive behavior affected patient care 45.6% of the time vs. 33% who said it did not, and 21% who did not know. Additionally it appeared that disruptive behavior (Crosstab table with job title) negatively impacted (disrupted) patient care (χ2 = 9.92, df = 12, P = 0.62).

Organizational disruptive behavior policies and procedures decrease incidence of disruptive behavior

In programs with disruptive behavior policies, 47% saw a decrease in disruptive behavior vs. 40.5% where there were no policies in place (χ2 = 30.03, df = 4, P < 0.001) vs. a lower 33% decrease when responders were not sure whether such a policy existed.

DISCUSSION

Federation of state medical boards

The Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) takes the issue of disruptive behavior seriously, and issues policy statements regarding physician impairment and disruptive behaviors involving the healthcare team.[3] The FSMB revised its 1995 guide to state medical and osteopathic boards to educate the public regarding physician impairment, illness, and health programs available to physicians. The FSMB also observed; “Disruptive behavior impairs the ability of the healthcare team to function effectively, thereby placing patients at risk.”[3] These and other comparable statements have been similarly issued by other agencies and medical/nursing societies to increasingly deal with disruptive behaviors.

The joint commission

Regulatory agencies such as The Joint Commission (TJC), the Institute of Medicine (IOM), and clinical societies like the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN) and the ACPE have written policy statements denouncing disruptive behaviors in healthcare organizations.[1,2] The AACN wrote their position statement to recognize that abusive behavior from physicians made it increasingly difficult to recruit and retain qualified nurses in the workplace.[1] In the ACPE position statement of 2010, they acknowledged that disruptive behaviors (e.g. aggression, harassment, and intimidation) can negatively affect the healthcare team's ability to work together, and negatively impact the quality of patient care.[2]

Breakdown in communicating leads to medical errors

Studies have shown that disruptive behavior contributes to a breakdown in communication that threatens the quality of patient care, and increases the incidence of medical errors.[4,7,10] Longo states; “Disruptive behaviors threaten patient well being due to a breakdown in communication and collaboration.”[7] Reynolds describes disruptive behavior with the following behavioral manifestations: yelling, threatening gestures, foul and abusive language, and public criticism of coworkers.[10] He also describes passive-aggressive behaviors that potentially interfere with patient care such as: intentional miscommunication, not answering or delaying answers to pages, and/or impatience with questions. Jericho et al. further reported that the incidence of wrong site surgeries is on the rise because disruptive providers deliberately ignore the “time out” system process before a procedure.[4]

Findings in our survey vs. 2009 Doctor–Nurse behavior survey

It is important to compare the results of the 2009 Doctor–Nurse Behavior Survey with our study vs. the Johnson study.[5] The respective institutions experienced behavior problems between doctors and nurses; 97.2%of the time in their survey vs. our finding of 82%.[5] One explanation for this difference may be that respondents in the 2009 study were either nurse executives or physician executives, while respondents in the current study included many different providers (e.g., staff nurses, physicians, mid-level providers, and administrators).[5] A second explanation may be that the current study found differences in the frequency of organizational disruptive behavior by different providers (Physicians-69%, Nurses-19%, NP/PA-3.8%). A third explanation may be that more respondents in the 2009 survey worked in a hospital, integrated health system, or academic medical centers (where a higher level of disruptive behavior was noted) vs. the current study.

Perceived organizational rate of disruptive behavior

The perceived organizational rate of disruptive behavior is very likely to be dependent on the size of the organization; as institutions grow, there is a greater chance of observing disruptive behavior. The size effect is partially responsible for the higher level of organizational disruptive behavior in hospitals vs. private practice settings, while there were no such significant differences in the rates of personally experienced disruptive behavior in these settings.

Import of clearly constructing questions about organizational perception of disruptive behaviors

It is important to clearly construct the questions about organizational perception of witnessed and personal disruptive behaviors to ensure reliable/reproducible responses. For instance, witnessed and personal encounters would more likely be interpreted as more accurate assessments of disruptive behavior.

Import of location on frequency of disruptive behaviors

More frequent disruptive behaviors are described in large patient care and high stress areas. For example, high acuity and high stress patient care areas such as the OR, emergency department (ED), labor and delivery, and ICUs are fraught with tales of bad behavior from healthcare providers.[6,8,12,13] The current study found a statistically higher incidence of witnessed disruptive behaviors in different hospital locations; the highest were the ICU and ER, followed in descending order by the OR, and the “floor.”

Others observe higher prevalence of disruptive behavior in perioperative setting

Multiple articles in the Association of Operating Room Nurses (AORN) Journal and the Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing discuss a higher prevalence of disruptive behavior in the perioperative setting.[11,13] According to Saxton et al., between 74% and 92.5% of nurses, physicians, and administrators reported witnessing or experiencing disruptive behavior in perioperative areas.[12] Rosenstein reported a study of 244 participants who were asked, “Have you ever witnessed disruptive behaviors in the perioperative area…”; the answer was yes from 75% of attending surgeons, 64% of anesthesiologists, 59% of nurses, and 43% of surgical residents.[11] Kaplan et al. stated that “For organizations embarking on changing disruptive behavior, the OR is perhaps the most obvious place to start” (p. 496).[6] Other articles named factors such as high volume/high complexity in the OR setting as contributing to disruptive behavior.[8] However, the fact that there were no differences in the rate of personally experienced or perceived disruptive behavior at the institutional level argues that the problem is more complex than just simple stress. This is especially true when only 32% of respondents endorsed “stress” as a cause of disruptive behavior. Additional studies may help elucidate these answers in the future.

Will this information help prevent future disruptive behavior?

Will any of this information help reduce or prevent disruptive behavior in the future? Certainly, we found that the perception of disruptive behavior alone does not eliminate it; for example, physician respondents who were the most aware of disruptive behaviors, were still the most likely to “misbehave.” However, although disruptive behavior policies did not affect the perceived prevalence of disruptive behavior, they did reduce the rate of these behaviors.

Stopping disruptive behaviors limit adverse events and mortality

As our survey indicated that 45.6% of respondents found that disruptive behaviors at their institutions affected patient care, stopping such behaviors is of paramount importance. In Rosenstein and O’Daniel's survey, 67% of respondents observed that disruptive behaviors were linked to adverse events, and 27% reported patient mortality as a consequence of those events.[11] Veltman's survey similarly reported that disruptive behavior that led to “near misses” (17 of 32 respondents), and that13 of 31 respondents noted that it contributed to specific adverse outcomes.[13]

Disruptive behavior policies to protect/maintain quality patient care

Limiting the impact of disruptive behaviors (e.g. adverse events and mortality) and maintaining/improving the quality of patient care prompted TJC's institution of disruptive behavior policies. Questions surrounding these policies included: are the policies current, are they reviewed periodically, are they enforced, and are there consequences to violating these policies? Strategies to reduce/stop disruptive behaviors included mediated conversation between the parties, conforming medical staff by-laws to organizational standards/policies, counseling, and education. Education may vary from establishing early awareness in medical and nursing schools, to creating workshops to develop codes of conduct, promote assertiveness training, and enact preventive measures.

Need for proactive approach to limiting/eliminating disruptive behavior

Organizations must be proactive in reducing/stopping disruptive behaviors among their employees. Depending on the prevalence within an institution, committees or task forces can be created to investigate and resolve complaints. If these efforts fail, especially in instances of repeated infractions, the termination of employment must be listed as an option. One must also consider legal ramifications that may arise if disruptive behavior is not addressed. In the healthcare industry, employees can and will litigate when grievous circumstances are not resolved/addressed through their employers. This places institutions at risk for liability, and can tarnish their reputation.

Creating policies for disruptive behavior

Quantifying disruptive behaviors is an important step in reducing their frequency in the future. As organizations seek hard data that impacts not only their reputation (e.g. quality of patient care), but conceivably their bottom line, senior management should direct more resources toward creating policies that will address the issue of disruptive behavior by providers in the workplace.

CONCLUSION

It is no longer acceptable for the healthcare industry to allow disruptive behavior to permeate its institutions. The IOM and TJC have identified disruptive behavior as a major barrier to attaining the highest quality and safest patient care. Multiple studies along with our own document that disruptive behaviors torpedo morale, increase turnover, decrease staff/patient satisfaction, and most importantly, result in poorer outcomes. Structured organizational disruptive behavior policies, organizational commitment, and education should help reduce/limit, and eventually eliminate these behaviors. Certainly, healthcare institutions, by adopting and enforcing these policies, should be able to significantly increase both patient and staff satisfaction by creating a healthier work environment.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com/text.asp?2013/4/6/375/120781

Disclaimer: The authors of this article has no conflict of interest to disclose, and have adhered to SNI's policies regarding human/animal rights, and informed consent. Advertisers in SNI did not ask for, nor did they receive access to this article prior to publication.

Contributor Information

Mona Stecker, Email: mkstecker@Winthrop.org.

Nancy Epstein, Email: nancy.epsteinmd@gmail.com.

Mark M. Stecker, Email: MStecker@Winthrop.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Zero Tolerance for Abuse. Position Statement. 2012:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Board of Governors; American College of Healthcare Executives. American College of Physician Executives. Preventing and addressing workplace abuse: Inappropriate and disruptive behavior. Healthc Exec. 2011;26:98–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federation of State Medical Boards. Policy on Physician Impairment. 2011:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jericho BG, Mayer D, McDonald T. Behaviors in Healthcare. 2011;28:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson C. Bad blood: Doctor-nurse behavior problems impact patient care. Physician Exec. 2009;35:6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan K, Mestel P, Feldman DL. Creating a culture of mutual respect. AORN J. 2010;91:495–510. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longo J. Combating disruptive behaviors: Strategies to promote a healthy work environment. 2010;15:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel P, Robinson BS, Novicoff WM, Dunnington GL, Brenner MJ, Saleh KJ. The disruptive orthopaedic surgeon: Implications for patient safety and malpractice liability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:e1261–6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: A persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006;3:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds NT. Disruptive physician behavior: Use and misuse of the label. J Med Regul. 2012;98:8–19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenstein AH, O'Daniel M. Impact and implications of disruptive behavior in the perioperative arena. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxton R. Communication skills training to address disruptive physician behavior. AORN J. 2012;95:602–11. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veltman LL. Disruptive behavior in obstetrics: A hidden threat to patient safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:587.e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]