Abstract

Purpose:

To determine the frequency of diabetic retinopathy and its risk factors in diabetic patients attending the eye clinic at the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI).

Materials and Methods:

This was a prospective cohort study of diabetic outpatients attending the Eye Clinic at the UHWI. Data were collected on age, gender, type of diabetes mellitus (DM), type of diabetic retinopathy, other ocular diseases, visual acuity, blood glucose and blood pressure.

Results:

There were 104 patients (208 eyes) recruited for this study. There were 58.6% (61/104) females (mean age 53.6 ± 11.9 years) and 41.4% (43/104) males (mean age 61.7 ± 12.1 years). Type II DM was present in 68.3% (56% were females) of the patients and Type I DM was present in 31.7% (69.7% were females). Most patients (66%) were compliant with their diabetic medications. The mean blood glucose was 11.4 ± 5.3 mmol/L. Elevated blood pressure (<130/80) was present in 82.7% of patients. The mean visual acuity was 20/160 (logMAR 0.95 ± 1.1). The frequency of diabetic retinopathy was 78%; 29.5% had background retinopathy, and 50.5% of eyes had proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) of which 34% had tractional retinal detachments. The odds ratio of developing PDR was 1.88 (95% confidence intervals (CI): 1.02-3.3) for Type I DM compared to 0.74 (95% CI: 0.55-0.99) for Type II DM. PDR was more prevalent in females (χ2, P = 0.009) in both Type I and II DM.

Conclusions:

Jamaica has a high frequency of PDR which is more common in Type I diabetics and females. This was associated with poor glucose and blood pressure control.

Keywords: Compliance, Diabetic Control, Diabetic Retinopathy, Hypertension, Jamaica

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic retinopathy can result in ocular complications leading to poor vision in the working age group. It is one of the leading causes of blindness in the 20-74 years age group.[1] There are approximately 34 million people in America with Diabetes Mellitus (DM).[2] Jamaica, a developing country, is the largest English speaking country in the Caribbean with a population of 2,709,300.[3] The gender adjusted prevalence of DM in Jamaica is 9.5% (95% confidence intervals (CI): 7.0-12.0) for males and 15.7% (95% CI: 13.2-18.3) for females.[4] Eighty-one percent of Jamaican patients in a diabetic study had a body mass index (BMI) <25 kg/m2, 77% had a HbA1C < 6.5% and a 63% had a systolic blood pressure < 130 mmHg.[5,6] The median HbA1C was 8.3 in the Jamaican study population.[7] Uncontrolled diabetic patients particularly with associated hypertension are more likely to have diabetic retinopathy, which increases with the duration of their diabetes.

There is literature on the glycemic control and barriers to diabetic care in Jamaica but none on the frequency of diabetic retinopathy. This prospective observational study was designed to look at the present frequency of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic control of patients in the Eye Clinic at the University Hospital of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One hundred and four consecutive patients were recruited from the Retina Clinic at the University Hospital of the West Indies, Jamaica over a two-month period. The inclusion criteria were diabetic patients from the Retina Clinic, who were able to answer the questions and gave voluntary informed consent. Patients were excluded if they had previous ocular trauma or were unable to communicate. All patients were dilated with topical tropicamide 1% and topical phenylephrine 2.5% and underwent mydriatic funduscopy examination at the slit lamp.

Background diabetic retinopathy (BDR) was defined according to the presence of dot and blot hemorrhages, hard exudates or retinal thickening. Pre-proliferative changes were defined as the presence of cotton wool spots, intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMA) and vascular dilatation and beading. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) was defined as the presence of neovascularization at the disc or elsewhere, or the presence of a tractional retinal detachment or vitreous hemorrhage. Macula edema was defined as retinal thickening involving the fovea.

Patients were assessed to determine if they were compliant with their medications. They were graded as fully compliant if they adhered to their medication routinely and not compliant if they didn’t take all their medications daily. A questionnaire was completed by the ophthalmologist seeing the patient. Each patient gave informed consent; anonymity and confidentiality was maintained during the study in keeping with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000. Data were collected on age, gender, type of diabetes mellitus (DM), duration, retinal status, other ocular diseases, visual acuity, blood glucose and blood pressure, compliance with medications and ophthalmic management plan. Ethics approval was obtained from the University Hospital of the West Indies Ethics Committee. Descriptive statistical analysis, means test with the chi square test (χ2) were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 19.0).

RESULTS

There were 104 patients (208 eyes) recruited for this study. There were 58.6% (61/104) females (mean age 53.6 ± 11.9 years; range 28-83 years) and 41.4% (43/104) males (mean age 61.7 ± 12.1 years; range 31-85 years). Females were statistically significantly younger than males (P > 0.001).

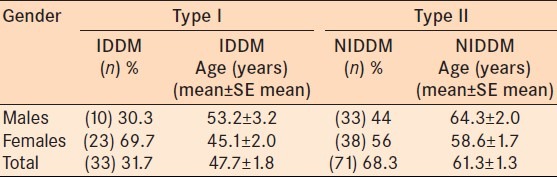

In our study population, 31.7% (33/104) of subjects were Type 1 Insulin Dependent Diabetic Mellitus (IDDM group) patients. There were 33 patients, 23 females and 10 males, in the Type 1 IDDM group [Table 1]. There were 71 patients, 38 females and 33 males who were Type II Non-Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus patients (NIDDM group) [Table 1]. Females were more commonly affected in the Type I IDDM group (69.7%) compared to the Type II NIDDM group (56%) [Table 1]. The mean age was 47.7 ± 1.8 years for the IDDM group and 61.3 ± 1.3 years for the NIDDM group.

Table 1.

Demography of the population: Age according to gender and type of DM

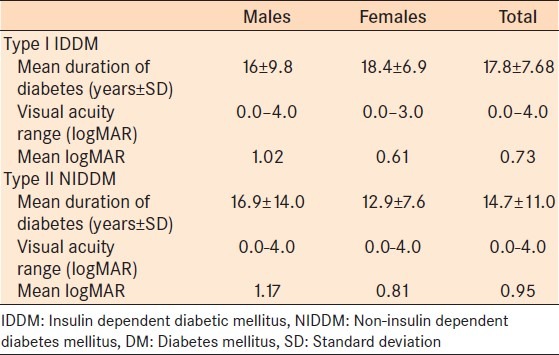

The duration of the diagnosis of diabetes ranged from 4 months to 45 years in the entire study population with a mean of 17.8 ± 7.7 years [Table 2].

Table 2.

Duration of Diabetes Mellitus and Visual Acuity (LogMAR)

Compliance with diabetic medications

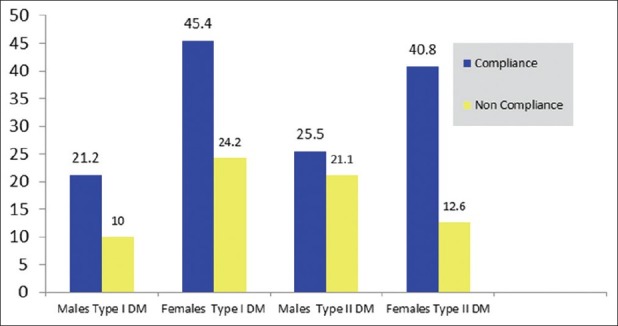

There were 66.6% (7 males and 15 females) compliant patients in the IDDM group. There were 66.2% (18 males and 29 females) compliant patients in the NIDDM group. There was no statistical association between compliance and the type of diabetes (P = 0.96; χ2 test).

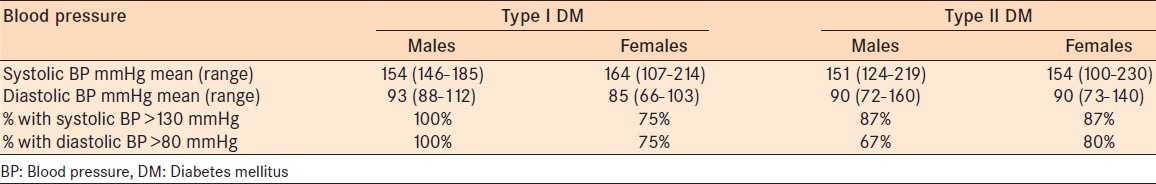

Females were more compliant than males for the total group and for each type of DM [Figure 1]. There were 45.4% compliant females in IDDM group and 40.8% compliant females in the NIDDM group. There was no statistical difference between compliance with medications according to gender in the study population (P = 0.35; χ2 test) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Percentage compliance according to gender in Type I vs. Type II Diabetes Mellitus

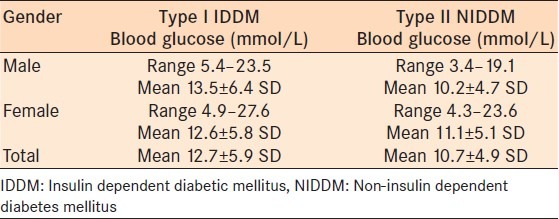

Blood glucose control

The random blood glucose ranged from 3.4 to 27.6 mmol/L with a mean glucose of 11.4 ± 5.3 mmol/L for the total group. The NIDDM group had a lower mean blood glucose of 10.2 ± 4.7 mmol/L versus the IDDM group 12.7 ± 5.9 mmol/L [Table 3]. There was no correlation between duration of diabetes and good sugar control (Pearson's correlation coefficient = 0.056; P = 0.29). There was little correlation between older patients (<60 years old) and good glucose control (Pearson's correlation coefficient = -0.154; P = 0.06).

Table 3.

Blood glucose levels of the patients according to type I and II DM

Blood pressure levels

Elevated blood pressure was defined as <130 mmHg (systolic) and <80 mmHg (diastolic) in 82.7% of the entire study population. There were 66.7% hypertensives in the IDDM group and 88.7% in the NIDDM group. The systolic values ranged from 100 to 230 mmHg and the diastolic values ranged from 64 to 160 mmHg for the entire study population. In both groups the mean systolic and diastolic values were higher than the accepted blood pressure for a diabetic (BP 130/80). The Type IDDM group had a mean BP of 154/93 and 164/85 for males and females, respectively. However, all males in the IDDM group had BP < 130/80, compared with 75% of females [Table 4]. In the NIDDM group the mean BP was 151/90 and 154/90 in males and females, respectively [Table 4]. In the NIDDM, 87% of both males and females had a systolic blood pressure of <130 mmHg.

Table 4.

Blood pressure measurements according to gender and type of DM

Visual acuity: (According to type of diabetes and gender)

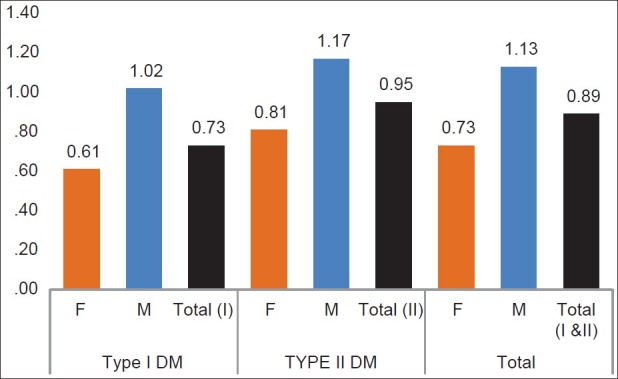

Visual acuity ranged from 6/6 to no light perception with a mean of 0.89 ± 1.1 logMAR for the entire study population group [Figure 2]. The IDDM group had statistically significant better mean visual acuity (0.73 ± 0.9 logMAR) compared to the NIDDM group (0.95 ± 1.1 logMAR) (P = 0.02). Females had better visual acuity than males in both group [Figure 2]. With respect to gender, for the IDDM group, the mean visual acuity was 0.61 ± 0.8 logMAR in females and 1.0 ± 1.2 logMAR in males (P = 0.79). In the NIDDM group, the mean visual acuity was 0.81 ± 1.0 logMAR versus 1.17 ± 1.2 logMAR for females and males, respectively (P = 0.54).

Figure 2.

Mean logMAR visual acuity of patients (According to Type I and II DM and Gender)

Frequency of diabetic retinopathy

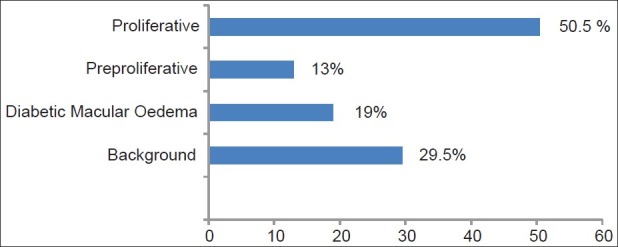

Diabetic retinopathy was present in 78% of the patients. Background DR was present in 29.5% of patients with DR [Figure 3]. Macular edema was present in 19% of patients. Pre-proliferative diabetic retinopathy was the least frequently occurring type of DR, occurring in 13% of cases. However, 50.5% of eyes had proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) with neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage and/or tractional retinal detachment.

Figure 3.

Frequency of Diabetic Retinopathy in our study population

Of the patients with PDR, 34% had tractional retinal detachments and 14% had vitreous hemorrhages. The remaining 52% of patients with PDR had neovascularization at the disc and elsewhere, which placed them at high risk of visual loss unless they received adequate and timely laser treatment.

In the IDDM group, 66.6% of patients had PDR, compared with 41.2% in the NIDDM group. The Chi-squared analysis showed that the IDDM group was more likely to get PDR (P = 0.034). Thus patients in the IDDM were more susceptible/prone to visual loss.

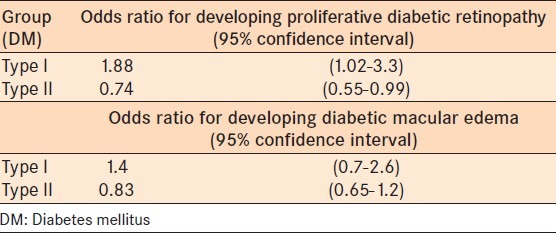

The odds ratio of developing PDR was 1.88 (95% CI 1.02-3.3) in the IDDM group compared to 0.74 (95% CI 0.55-0.99) in the NIDDM (Fisher's Exact test P = 0.028) [Table 5]. Further statistical analysis showed that females were more likely to have PDR than males in both groups (P = 0.009).

Table 5.

Odds ratio of developing visual threatening diabetic retinopathy (i.e., proliferative diabetic retinopathy or macula edema)

Although our study showed that patients in the IDDM group were more likely to get diabetic macula edema compared to the Type II NIDDM group (odds ratio: 1.4 versus 0.83), this was not statistically significant (Fisher's exact test P = 0.21) [Table 5].

Other comorbidities

Cataracts were present in 39.4% (26/66 eyes) of the IDDM group and 55.6% (79/142 eyes) of the NIDDM group. Further cross tabulation analysis was performed within each group according to gender and age (in 2 groups: >59 years old and <60 years old). Females >59 years old were statistically significantly more likely to have cataracts than those <60 years (χ2; P = 0.001). Glaucoma was present in 18.2% (12/66 eyes) in the IDDM group and 13.4% (19/142 eyes) in the NIDDM group, one with rubeotic glaucoma.

Treatment

Forty percent (83/208) of eyes had previous laser treatment. Further treatment was required in 33.6% (70/208 eyes) of patients. Of these, 12.9% (9/70) required cataract surgery, 47.1% (33/70) required laser treatment and 40% (28/70 eyes) required vitrectomy.

DISCUSSION

Diabetes is an increasing healthcare problem, with the majority of those affected in the 40-59 years old age group, with low and middle income countries carrying a greater burden of the disease.[8] Loss of vision can have a significant impact on the independence and psychosocial aspect of a young adult, affecting their productivity.

The prevalence of DR is variable according to the country.[8] The global prevalence of DR is 34.6%.[9] The prevalence of DR at first screening in the United Kingdom is 35% and in Scotland 19%.[10,11] Other studies have reported prevalences at 42% (Cairo), 54.9% (Yemen) and 64.1% (Jordan).[12,13,14]

Low rates of DR have been reported in Oman (14.5%), Lebanon (17%) and the United Arab Emirates (19%).[15,16,17] This variation can be due to lifestyles, culture, diet and free accessibility to health care (e.g., Oman).[15] The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study on Diabetic Retinopathy (WESDR) showed that the prevalence was more common in the younger onset group compared to the older onset group; 23% versus 10%.[18] In the USA, the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in adults <40 years was 40.3%; however, the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in all age groups was 3.4%.[19]

Our study showed that 78% of our study population had diabetic retinopathy, which is comparable to African/Afro-Caribbean rates in the UK with a prevalence of 54% for diabetic retinopathy and 11.5% sight threatening diabetic retinopathy.[20] However, the frequency of sight threatening disease was much higher.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) includes neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage and tractional retinal detachments, which can lead to visual loss. Patients with PDR have a 4 year increased risk of visual loss, cardiac, kidney disease and death.[18] PDR requires early intervention which ranges from laser treatment (panretinal photocoagulation, PRP) to complex vitreoretinal procedures for tractional retinal detachments.

The prevalence of PDR globally is 6.9% and in the USA (adults < 40 years old) it is 8.2%. These values contrast greatly to the prevalence in our clinic of 50.5% for PDR.[9] The prevalence of diabetic macular edema varies from 0.85 to 12.3% worldwide, which is lower than our prevalence of 19%.[9,15]

The increased prevalence of PDR and diabetic macula edema may be related to our study population's systemic factors and culture. The Jamaican study patients had a 63% compliance with their diabetic medication and their mean blood glucose levels were elevated in both groups. The IDDM patients who had both a higher mean blood glucose and blood pressure were more likely to develop PDR and diabetic macula edema. Poor compliance leading to elevated blood glucose (uncontrolled diabetes) are well recognized risk factors for progression of DR.

The blood pressure was elevated in 82.7% of the entire study population in the current study. The prevalence of hypertension was 30.8% in our experience for patients <15 years old and is more commonly seen in females, diabetics and obese patients.[21,22] Diabetics had twice the risk of developing hypertension compared with non-diabetics from the Jamaican Hypertension prevalence study.[22] In our study, with respect to hypertension in the IDDM group, 100% of males and 75% of females had blood pressure < 130/80 (BP 130/80 is recommended by the UKPDS study).[10] Poor blood pressure control could be one of the risk factors for the severity of DR.[10]

In previous studies of the Jamaican population, <80% of diabetic patients had a BMI < 25 kg/m2 and 77% had an HBA1c < 6.5%, with a median HBA1c of 8.0.[5,6,7] Obesity and poor glucose control are significant factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy. Our study did not assess the BMI, but should be evaluated in future studies.

Ethnicity may also have a role in the prevalence of DR, which is more aggressive in blacks compared to whites.[20,23,24,25,26,27,28] Emanuele et al. studied the effect of ethnicity and other factors on diabetic retinopathy but did not find that it was directly related to the traditional risk factors of duration, HbA1C and blood pressure.[23] However, there is agreement that duration of diabetes, high blood pressure, microalbuminuria, fibrinogen and having had amputations were associated with more severe diabetic retinopathy (proliferative and macular edema) in black patients.[23,27,28]

Hispanics have a higher prevalence of macula edema, three times higher than whites, whereas Afro-Americans had a ×2.5 higher prevalence compared to whites.[23] Wong et al.'s multi-ethnic US cohort study showed that the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy was higher in Afro-Americans versus whites (36.7% vs. 24.8%) and that they had a ×5 higher risk of clinically significant macula edema over whites.[29]

Significant eye disease require significant hospital resources and 33.6% of the eyes in our study needed surgical intervention. This high percentage may be due to the fact that the sampled patients are from an eye clinic in a tertiary institution, University Hospital, which is the only hospital with a specialist retina eye clinic on the island (pop 2.7 million). Therefore, the more severe cases would have been included in our sample. With 47.1% requiring laser and 40% requiring vitrectomy surgery, this has a significant impact on limited hospital resources in our region.

The prevalence of DR worsens with increasing duration, poor control and associated comorbidities such as hypertension. Our Jamaican patients are more likely to have higher BMIs, uncontrolled hypertension and elevated HBA1C. These may be risk factors for the significantly high percentage of PDR in our country, which impacts our health resources and productivity of our visual-impaired diabetic patients in the working age group. If this is not controlled we can expect that prevalence of DR will increase.

The prevalence of DR is decreasing in the USA and this has been linked to the increasing DR surveillance programs, intensive risk factor control and improving health care systems.[23,24] Underdeveloped nations should be doing more to control diabetes, in order to prevent the progression to visually threatening macular edema or PDR. This puts a strain on limited hospital resources (equipment; i.e., vitrectomy machine and laser procurement and maintenance).

Efforts should be aimed towards diabetes screening (early detection and referral) and education on diabetic control and the modifiable risk factor controls (glucose, hypertension, obesity and dyslipidemia). In this study, blood cholesterol was not assessed, but could also help to highlight or correlate the increasing ischemia and poor vision from macular edema and PDR. The burden and cost of the disease is heavy for an underdevelopment country. In addition to this, the impact of visual impairment in our country that neither recognizes nor has government policies that compensate for low vision, blindness or any visual disability can be significant. Diabetic eye screening is important and public awareness amongst both the general population and family physicians can result in an earlier referral to the ophthalmologists for management, thereby, reducing the risk of visual morbidity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bloomgarden ZT. Diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1080–3. doi: 10.2337/dc08-zb05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995-2005: Prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1414–31. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Government of Jamaica. Statistics: Demography: Population. 2012. [Last accessed 2012 Dec 14]. Available from: http://statinja.gov.jm/Demo_SocialStats/population.aspx .

- 4.Barcelo A, Rajpathak S. Incidence and prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the America. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2001;10:300–8. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892001001100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wint YB, Duff EM, McFarlane-Anderson N, O’Connor A, Bailey EY, Wright-Pascoe RA. Knowledge, motivation and barriers to Diabetic control in Adults in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2006;55:330–3. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442006000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor A, McFarlane-Anderson N, Duff EM, Wright Pascoe R, Wint YB. High levels of F2-Isoprostanes in Jamaican adults with diabetes mellitus. Int J Diabetes Metab. 2006;14:51–4. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442006000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duff E, O’Connor A, McFarlane-Anderson N, Wint YB, Bailey EY, Wright Pascoe RA. Self care, compliance and glycaemic control in Jamaican adults with diabetes mellitus. West Indian Med J. 2006;55:232–6. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442006000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Global Burden of the Disease. The International Diabetes Federation, Diabetes Atlas. 5th ed. 2012. [Last accessed on 2012 Jun 16]. Available from: http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas/5e/the.global.burden .

- 9.Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux EL, Kowalski JW, Bek T, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Meta-Analysis for Eye Disease (META-EYE) Study Group. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–64. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Looker HC, Nyangoma SO, Cromie D, Olson JA, Leese GP, Black M, et al. The Scottish Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Collaborative and the Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group. Diabetic retinopathy at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in Scotland. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2335–42. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2596-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herman WH, Aubert RE, Engelgau MM, Thompson TJ, Ali MA, Sous ES, et al. Diabetes mellitus in Egypt: Glycaemic control and microvascular and neuropathic complications. Diabetes Med. 1998;15:1045–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(1998120)15:12<1045::AID-DIA696>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bamashmus M, Gunaid A, Khandekar R. Diabetic retinopathy, visual impairment and ocular status among patients with diabetes mellitus in Yemen: A hospital-based study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:293–8. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.53055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Till MI, Al-Bdour MD, Ajlouni KM. Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment among Jordanian diabetics. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15:62–8. doi: 10.1177/112067210501500110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khandekar R, Al Lawatii J, Mohammed AJ, Al Raisi A. Diabetic retinopathy in Oman: A hospital based study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1061–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.9.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waked N, Nacouzi R, Haddad N, Zaini R. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy in Lebanon. J Fr Ophthalmol. 2006;29:289–95. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(06)73785-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Maskari F, El-Sadig M. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United Arab Emirates: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Ophthalmol. 2007;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE. Epidemiology of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:1875–91. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.12.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Eye Diseases Research Prevalence Research Group. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:552–63. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivaprasad S, Gupta B, Gulliford MC, Dodhia H, Mohamed M, Nagi D, et al. Ethnic variations in the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in people with diabetes attending screening in the United Kingdom (DRIVE UK) PLoS One. 2012;7:e39608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalljie GR, Lalljie SE. Characteristics and control of severe hypertension in a specialist, private practice in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2005;54:315–8. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442005000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ragoobirsingh D, McGrowder D, Morrison EY, Johnson P, Lewis-Fuller E, Fray J. The Jamaican hypertension prevalence study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:561–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emanuele N, Sacks J, Klein R, Reda D, Anderson R, Duckworth W, et al. Ethnicity, race, and baseline retinopathy correlates in the veterans affairs diabetes trial. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1954–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruickshank JK, Alleyne SA. Black West Indian and matched white diabetics in Britain compared with diabetics in Jamaica: Body mass, blood pressure, and vascular disease. Diabetes Care. 1987;10:170–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein R, Sharrett AR, Klein BE, Moss SE, Folsom AR, Wong TY, et al. The association of atherosclerosis, vascular risk factors, and retinopathy in adults with diabetes: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1225–34. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabb MF, Gagliano DA, Sweeney HE. Diabetic retinopathy in blacks. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:1202–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.11.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egede LE, Mueller M, Echols CL, Gebregziabher M. Longitudinal differences in glycemic control by race/ethnicity among veterans with type 2 diabetes. Med Care. 2010;48:527–33. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d558dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emanuele N, Moritz T, Klein R, Davis MD, Glander K, Khanna A, et al. Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial Study Group. Ethnicity, race, and clinically significant macular edema in the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial (VADT) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;86:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong TY, Klein R, Islam FM, Cotch MF, Folsom AR, Klein BE, et al. Diabetic retinopathy in multi-ethnic cohort in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:446–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]