Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study is to estimate the prevalence of topical ocular anesthetic abuse among welders in Iran and suggest public health solutions for this issue.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, 390 welders were randomly recruited and queried on the use of anesthetic drops. A questionnaire was administered through structured one-on-one interviews conducted by the first author.

Results:

A total of 314 welders (80.5%) declared that they had used topical anesthetics at least once during their working lives. Almost 90% of them stated a preference for self-treatment over seeking help from a physician due to cultural and financial reasons. The most commonly used topical anesthetic was tetracaine. Most of the subjects (97.4%) had obtained the drugs from pharmacies without a prescription.

Conclusions:

The prevalence of topical ocular anesthetic abuse among welders in Iran is alarmingly high and may partially be due to cultural issues. Although most physicians are aware that topical anesthetics should only be used as a diagnostic tool, there is a crucial need to re-emphasize the ocular risks associated with chronic use of these medications. Educational programs for both physicians and the public are necessary to address the problem.

Keywords: Iran, Topical Ocular Anesthetics, Welder

INTRODUCTION

Today's ophthalmologists and their patients are fortunate to have many topical medications on hand for the treatment of a broad variety of ocular disorders. Topical ocular anesthetics play a vital role in the diagnosis and treatment of ocular diseases. The five most commonly used topical ophthalmic anesthetics are proparacaine, tetracaine, benoxinate (oxybuprocaine), lidocaine and cocaine, which are typically used for topical anesthesia before eye surgery or during eye examinations in clinic.[1,2] Unlike injected anesthetic agents, which may be associated with a number of potentially sight threatening or even life threatening complications, topical anesthetics are only accompanied with minimum discomfort. Due to their short duration of action, they have the advantage of prompt post-operative visual rehabilitation. Additionally, their lower cost is an added advantage.[3,4,5]

Although topical ocular anesthetics are generally safe, complications may rarely occur from their use. Balanced prescribing for specific diagnoses in addition to careful clinical monitoring of the effects of treatment can minimize the risks. However, the arbitrary use of these medications is likely to do more harm than good. Local anesthetics restrain the corneal epithelial cell migration rate by damaging the superficial corneal epithelial microvilli.[6] They may also have a direct toxic effect on the stromal keratocytes.[7] Ring infiltrates have been described in association with topical anesthetic abuse.[8] Pathological mechanisms such as immunologic, irritation, toxic, cumulative deposition, photoimmunologic or phototoxic and microbial imbalance may occur. The ocular or adnexal tissues can respond to these insults by manifesting cutaneous changes including papillary, follicular, keratinizing, or cicatrizing conjunctivitis; ulcerative, vascularizing, or cicatrizing keratitis; hyper- or hypopigmentation; and infectious complications.[9,10,11,12]

The haphazard use of topical eye drops, the lack of prescription monitoring and the availability of over the counter (OTC) topical anesthetic eye drops are common factors in the predisposition to abuse these agents in developing countries.[13] Due to the nature of the welding industry, welders are highly prone to topical ocular anesthetic abuse. Of interest, welding is also a known risk factor for uveal melanoma.[14] To the best our knowledge, there is no published data addressing the frequency of ocular anesthetic abuse in an at-risk community. We conducted the current study to evaluate the prevalence of topical ocular anesthetic abuse among Iranian welders and propose strategies to address this issue.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted between January and April 2012 in Iran and included 390 welders. A list of all registered welders was acquired from the welding union of Kerman province and participants were randomly selected using statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) (version 15 for Windows; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to avoid selection bias. An 18-item questionnaire was used, which covered the subjects’ demographic information, history of self-treatment, topical anesthetic abuse and access to eye drops. The questionnaire was administered through structured one-to-one interviews conducted by the first author at the welder's office for added convenience. All participants were provided with an educational pamphlet on the risks of topical anesthetics abuse. Those who reported recently abusing topical anesthetics were referred to a participating hospital for treatment.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS. Pearson and Spearman's rank correlation coefficients and Chi-square tests were used to measure the association between variables. Adjusted frequency distributions were calculated along with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P > 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The current study was registered with the scientific committee at the Kerman University of Medical Sciences (KUMS), Iran. The clinical protocols were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the KUMS and all participants provided informed consent.

RESULTS

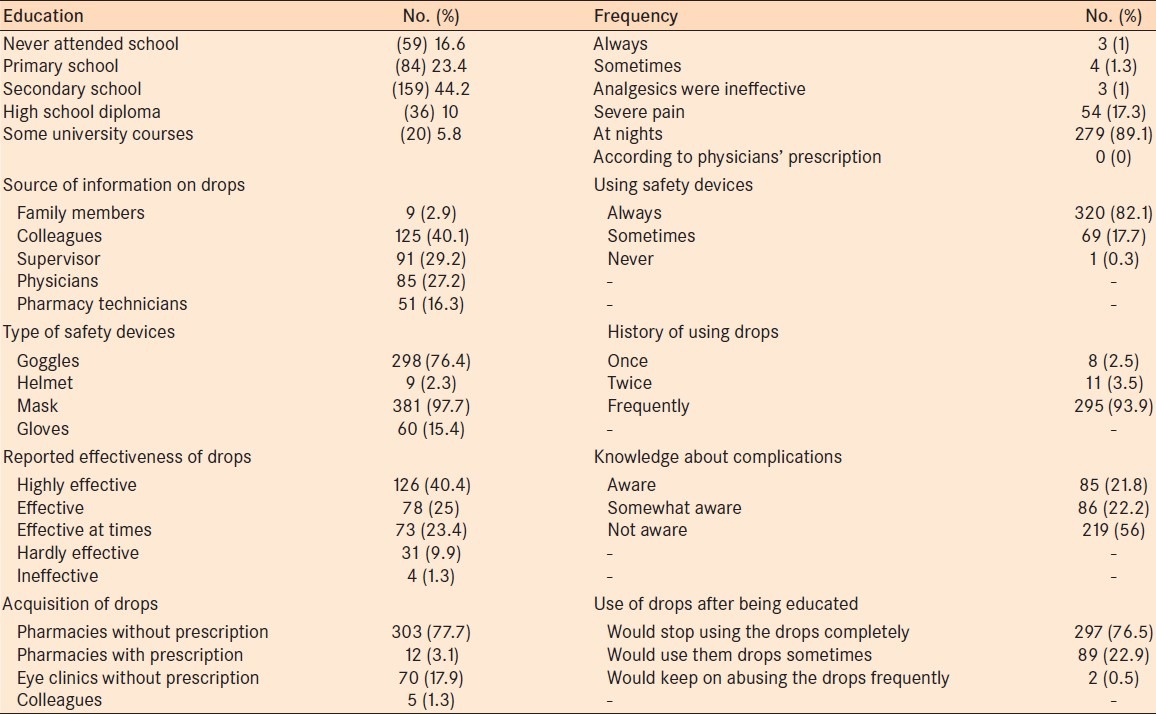

There were 390 welders included in the study. All subjects were male and the mean age was 37 ± 12 years (range 13-70 years), the majority (44.2%) had secondary level education, and their work experience ranged from 1 to 50 years. A total of 320 welders stated that they always wore safety devices and only one welder would refuse to wear safety devices. Most of the participants used goggles and masks believing that helmets and gloves were not necessary.

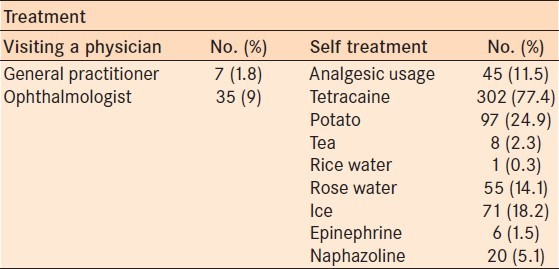

Out of 390 welders, 381 (97.7%; 95% CI: 95.7-98.9) had been exposed to an arc welding flash and 332 (85.1%; 95% CI: 81.2-88.5) had experienced metallic foreign body injury. Overall, 314 (80.5%; 95% CI: 76.58-84.44%) had used topical anesthetics at least once during their working lives. The initiating event that led to topical anesthetic usage was mostly exposure to an arc welding flash. The participants reported trying various self-treatments such as tetracaine drops, potato slices, cold compresses, and washing their eyes with tea, as well as visiting a physician [Table 1].

Table 1.

Frequency of treatment methods for welding flash used by participants

Welders reported a preference for self-treatment due to lack of time to visit a physician, the expenses involved, as well as spontaneous relief of symptoms. Over 10% believed eye drops to be hardly effective or ineffective altogether. Over half the participants had no idea of topical anesthetic abuse and its complications and 95.6% (95% CI: 93.1-97.4) had obtained the drops from pharmacies and eye clinics without a prescription from a physician. A total of 297 welders (76.5%; 95% CI: 71.6-80.3) declared that they would stop misusing topical anesthetic drops after they were provided with the educational pamphlets. No association was observed between the prevalence or frequency of topical anesthetic abuse and the age group and work experience (P < 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participants who reported abusing topical anesthetic drops

Surprisingly, those who had a higher level of education reported significantly greater misuse of drops than those who never attended school (P > 0.05); however there was no difference in the frequency of drop use between these groups. Despite the provision of free health-care at a nearby hospital, none of the referred participants showed up for treatment at the agreed appointment time.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a cross-sectional study to assess the prevalence of self-reported topical ocular anesthetic abuse among welders in Kerman, Iran. Ocular anesthetic abuse via self-medication was very common among welders; almost 80% reported using topical tetracaine after exposure to welding flash and more than 90% reported using anesthetic drops frequently. About 80% of the participants were unaware of the issue of topical anesthetic abuse and its complications, which may reflect a lack of awareness in the broader population. To our surprise, more than 90% of the welders reported purchasing the drops from drug stores and eye clinics without a prescription from a physician.

Whilst topical anesthetics are used frequently in ophthalmic diagnosis and surgery,[1,12,15] their potential toxicities are more often associated with their misuse and self-administration.[16,17] The literature has several case reports of ocular anesthetic abuse over the past 50 years. However, to our knowledge there are no published studies that describe the prevalence of this abuse in an at-risk population.[16,18,19,20] In 1968, Epstein and Paton described five patients who had used anesthetic drops frequently over a period of days to months.[21] In 2002, Ardjomand et al. described a patient suffering from keratitis with no response to treatment and significant ocular pain. Of note, this patient was a medical doctor himself.[22] Yagci et al. (2011) reported that out of 19 men (26 eyes) admitted to hospital, ten patients (52.6%) reported that they were using topical anesthetics and the remaining nine were discovered to have been using topical anesthetic drops during hospitalization.[23] In Iran, Sedaghat et al., reported a middle-aged man with history of topical tetracaine abuse suffering from corneal epithelial defect, ring infiltration and stromal edema in 2011.[20]

In Iran, like other developing countries, patients may acquire topical ocular anesthetics through several methods. Some of these medications are now available as low-cost, OTC remedies. Penna and Tabbara reported three patients who had obtained drops directly from the pharmacist.[13] Many pharmacies in Iran have attendants who prescribe medicines according to symptoms, which create the potential for misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment. In some regions in North America, pharmacists have recently been given prescribing privileges. Hence, this may be a global issue. The most commonly used topical anesthetic in Iran is tetracaine; a drop which is not on the list of OTC drugs in Iran and may cause a neurotrophic ulcer if abused. This alarming finding suggests a significant role for pharmacists in educating patients about the risks of ocular anesthetic use and supports the idea of continuing educational programs for pharmacists and clinical staff at different professional levels. Apart from pharmacies, some participants had obtained the drops from their colleagues at work and also reported the occasional practice of storing drops at their workplace for convenient access. Unsupervised patients may remove or steal topical anesthetics;[24] however, none of our participants reported having done so, presumably because drops are easily accessible.

We found that a high percentage of welders prefer self-medication over seeking care from health-care providers. Self-medication is a common practice world-wide, with prevalence as high as 73.9% in some developing countries.[25] Hughes et al.[26] suggested that becoming accustomed to self-medication can lead to the self-medication of prescription drugs and/or other inappropriate drug use.[27] We propose that this preference among the welders in our study has roots in both financial and cultural reasons. Most of them stated that the physicians would do nothing more than prescribe a number of drops. Some stated that physicians are expensive and visits are very time consuming. There were some participants who believed that no treatment was required as the pain would be gone in a few days. Due to the nature of their work and their financial circumstances, welders usually sought rapid relief of pain in order to return to work quickly.

Previous studies have reported variable results regarding the influence of factors such as education, age, socioeconomic status and availability of drugs on self-medication practices.[26,28,29] In this study, age and work experience were not significant predictors of ocular self-medication practices, whilst a higher level of education was significantly associated with more frequent topical anesthetic abuse. In a study in Sri Lanka, literates similarly self-medicated far more than illiterates.[30] There may also be a misperception of topical ocular anesthetics among some patient groups as a ‘magic cure-all.’ Many welders appear to become acquainted with anesthetic drops through colleagues, who are likely unaware of the possible adverse effects of misuse. After the welders were informed about the complications of misuse and given educational pamphlets, only 0.5% of them declared that they would keep on abusing the drops frequently. Given these findings and the increased risk of ocular melanoma among welders, there appears to be an important role for targeted education of this at-risk patient group with regards to eye health.

Drug utilization in developing countries is an important aspect of primary healthcare as governments have insufficient control of the drug supply system.[31] Most developed countries have control of OTC sales while perilous drugs such as sedatives and anesthetics are easily available in many developing countries. Iran has a system whereby almost any drug can be acquired in pharmacies without a prescription. Current legislation in Iran explicitly prohibits this practice; however, these laws are not strictly enforced and pharmacies do not face penalties for violating them. This may partly be explained by cultural factors, whereby many Iranians expect pharmacies to dispense drugs without a prescription. If a pharmacy complies with the law, consumers will simply use a competitor.[32]

There are some limitations to this study. Although we tried to reduce possible reporter and sampling biases, questionnaire-based studies are prone to biases. Currently there are no comparable studies available; hence, it is difficult to evaluate the validity of our findings. Conducting our study in one region and on one occupational group is likely to limit its accuracy and generalizability. Lastly, failure of the welders to present for treatment at the designated hospital could be considered another limitation of this study. We did our best to negotiate with the union to facilitate their attendance but to no avail.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, ocular anesthetic abuse in Iran is a matter of public health concern. Although many physicians may be aware of this fact, there appears to be a need to provide targeted education for welders and pharmaceutical staff. Reducing self-medication practices in Iran requires multi-targeted public health strategies, including mass education of the general public, intervention from health regulatory bodies and peer education programs for welders and other at-risk occupational groups. Further qualitative research could help refine our understanding of the practice of self-medication in Iran.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartfield JM, Holmes TJ, Raccio-Robak N. A comparison of proparacaine and tetracaine eye anesthetics. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1:364–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1994.tb02646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGee HT, Fraunfelder FW. Toxicities of topical ophthalmic anesthetics. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:637–40. doi: 10.1517/14740338.6.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crandall AS, Zabriskie NA, Patel BC, Burns TA, Mamalis N, Malmquist-Carter LA, et al. A comparison of patient comfort during cataract surgery with topical anesthesia versus topical anesthesia and intracameral lidocaine. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:60–6. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edge R, Navon S. Scleral perforation during retrobulbar and peribulbar anesthesia: Risk factors and outcome in 50,000 consecutive injections. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:1237–44. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)00143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tseng SH, Chen FK. A randomized clinical trial of combined topical-intracameral anesthesia in cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:2007–11. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)91116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns RP. Toxic effects of local anesthetics. JAMA. 1978;240:347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreira LB, Kasetsuwan N, Sanchez D, Shah SS, LaBree L, McDonnell PJ. Toxicity of topical anesthetic agents to human keratocytes in vivo. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:975–80. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rapuano CJ. Topical anesthetic abuse: A case report of bilateral corneal ring infiltrates. J Ophthalmic Nurs Technol. 1990;9:94–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenwasser GO. Complications of topical ocular anesthetics. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1989;29:153–8. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198902930-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramselaar JA, Boot JP, van Haeringen NJ, van Best JA, Oosterhuis JA. Corneal epithelial permeability after instillation of ophthalmic solutions containing local anaesthetics and preservatives. Curr Eye Res. 1988;7:947–50. doi: 10.3109/02713688808997251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldich Y, Zadok D, Avni I, Hartstein M. Topical anesthetic abuse keratitis secondary to floppy eyelid syndrome. Cornea. 2011;30:105–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181e458af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boljka M, Kolar G, Vidensek J. Toxic side effects of local anaesthetics on the human cornea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:386–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.5.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penna EP, Tabbara KF. Oxybuprocaine keratopathy: A preventable disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:202–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.3.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah CP, Weis E, Lajous M, Shields JA, Shields CL. Intermittent and chronic ultraviolet light exposure and uveal melanoma: A meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant SA, Hoffman RS. Use of tetracaine, epinephrine, and cocaine as a topical anesthetic in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:987–97. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82942-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen HT, Chen KH, Hsu WM. Toxic keratopathy associated with abuse of low-dose anesthetic: A case report. Cornea. 2004;23:527–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000114127.63670.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox B, Durieux ME, Marcus MA. Toxicity of local anaesthetics. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17:111–36. doi: 10.1053/bean.2003.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webber SK, Sutton GL, Lawless MA, Rogers CM. Ring keratitis from topical anaesthetic misuse. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1999;27:440–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1606.1999.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varga JH, Rubinfeld RS, Wolf TC, Stutzman RD, Peele KA, Clifford WS, et al. Topical anesthetic abuse ring keratitis: Report of four cases. Cornea. 1997;16:424–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sedaghat MR, Sagheb Hosseinpoor S, Abrishami M. Neurotrophic corneal ulcer after topical tetracaine abuse: Management guidelines. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13:55–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein DL, Paton D. Keratitis from misuse of corneal anesthetics. N Engl J Med. 1968;279:396–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196808222790802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ardjomand N, Faschinger C, Haller-Schober EM, Scarpatetti M, Faulborn J. A clinico-pathological case report of necrotizing ulcerating keratopathy due to topical anaesthetic abuse. Ophthalmologe. 2002;99:872–5. doi: 10.1007/s00347-002-0623-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yagci A, Bozkurt B, Egrilmez S, Palamar M, Ozturk BT, Pekel H. Topical anesthetic abuse keratopathy: A commonly overlooked health care problem. Cornea. 2011;30:571–5. doi: 10.1097/ico.0b013e3182000af9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocha G, Brunette I, Le François M. Severe toxic keratopathy secondary to topical anesthetic abuse. Can J Ophthalmol. 1995;30:198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Awad A, Eltayeb I, Matowe L, Thalib L. Self-medication with antibiotics and antimalarials in the community of Khartoum State, Sudan. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2005;8:326–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes CM, McElnay JC, Fleming GF. Benefits and risks of self medication. Drug Saf. 2001;24:1027–37. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124140-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins AP, Miranda Ada C, Mendes Z, Soares MA, Ferreira P, Nogueira A. Self-medication in a Portuguese urban population: A prevalence study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:409–14. doi: 10.1002/pds.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beitz R, Dören M, Knopf H, Melchert HU. Self-medication with over-the-counter (OTC) preparations in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2004;47:1043–50. doi: 10.1007/s00103-004-0923-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Worku S. Practice of self-medication in Jimma Town. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2004;17:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abosede OA. Self-medication: An important aspect of primary health care. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19:699–703. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel MS. Drug costs in developing countries and policies to reduce them. World Dev. 1983;11:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zargarzadeh AH, Minaeiyan M, Torabi A. Prescription and nonprescription drug use in Isfahan, Iran: An observational, cross-sectional study. Curr Ther Res. 2008;69:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]