Abstract

Macular detachment causes visual deterioration in 25-75% of patients with congenital optic disc pit. A number of treatment options have been reported to manage the macular detachment in optic pit. An optic disc pit represents a defect in the lamina cribrosa; theoretically, an ideal procedure to treat optic pit associated macular detachment would be one that prevents the flow of fluid across the pit by creating an additional barrier. We present a new surgical technique that employs an autologous internal limiting membrane (ILM) to create this barrier. The technique involves standard vitrectomy along-with ILM peeling. Subsequently, the peeled ILM was inverted and transplanted onto the optic disc pit to close the optic nerve pit. This technique showed satisfactory anatomic result with good functional improvement in visual acuity.

Keywords: Autologous, Internal limiting membrane, Optic disc pit, Serous macular detachment

INTRODUCTION

Congenital optic disc pit is a rare clinical entity, affecting approximately one in 11,000 people.[1,2] Patients with optic disc pit may remain asymptomatic, but 25-75% of patients present with visual deterioration in their third or fourth decade after developing serous macular detachment.[1,2] Treatment of optic disc pit with serous macular detachment remains challenging since the source of the fluid causing the macular detachment remains controversial. To treat this serous macular detachment, a number of treatment options have been reported. The most widely accepted treatment for such patients is a surgical approach involving pars plana vitrectomy with or without internal limiting membrane peeling and C3F8 endotamponade.[1]

An optic disc pit represents a defect in the lamina cribrosa.[2,3] Hence, the theoretically ideal procedure for reattaching the macula associated with an optic disc pit would be a procedure that prevents the flow of fluid across/through the pit by creating an additional barrier. We present a novel surgical technique where the patient's autologous internal limiting membrane (ILM) is transplanted onto the optic disc pit to create this barrier.

CASE REPORT

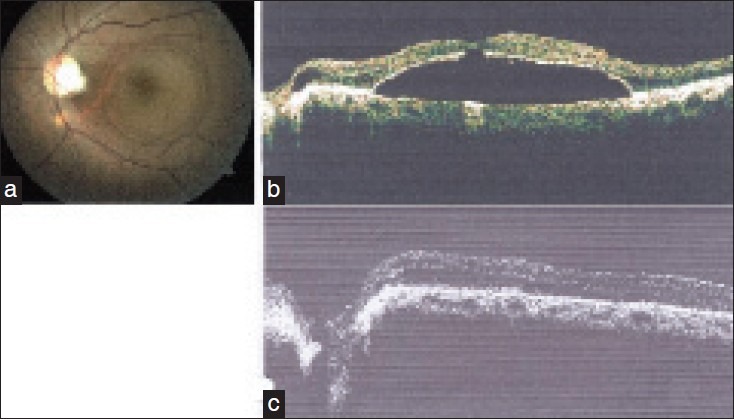

A 41-year-old female presented with a history of decreased vision in her left eye for 1 year. The best correctable visual acuity in that eye was 6/60. Anterior segment examination showed cortical cataractous changes. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was 16 mmHg. The left fundus showed an optic disc pit along-with a large macular detachment [Figure 1a]. Ocular coherence tomography (OCT - Stratus III, Carl Zeiss, Dublin, USA) of the macula was performed, which confirmed the clinical finding [Figures 1b and c]. The right eye was normal.

Figure 1.

(a) Preoperative fundus photograph. (b) Preoperative optical coherence tomography (OCT) showing macular detachment. (c) Preoperative OCT of optic disc pit

The patient was counseled on the available treatments. Then, we discussed the new technique which we were going to adopt for her surgery. The patient was also informed about the use of brilliant blue dye to stain the ILM during surgery. The patient signed an informed consent which contained all the details of the proposed surgical.

The patient underwent combined phacoemulsification and in-the-bag implantation of intraocular lens (+23.00 Diopter, Acrysof IQ, Alcon Laboratories, Tx, USA) and pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) combined with peeling of ILM. PPV was carried out with a 23-G sutureless technique. After initial core vitrectomy, triamcinolone assisted posterior hyaloid removal was performed. The ILM was stained with brilliant blue stain (Fluoron GmbH, Magirus-Deutz).

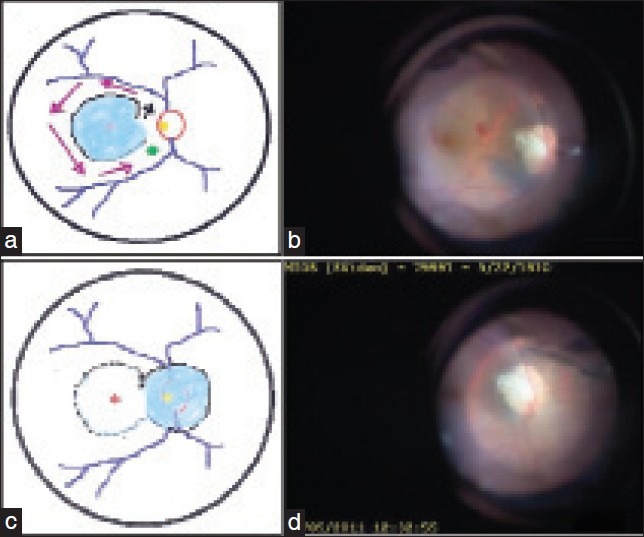

The stained ILM between the temporal vascular arcades was peeled in a manner that it was removed as a single sheet keeping the part adjacent to the superotemporal edge of optic disc still attached in a pedicle like fashion, as used in skin graft surgery [Figures 2a and b]. Then, the peeled ILM flap was inverted with 23-G ILM-forceps and reflected over the optic disc [Figures 2c and d. Fluid-air exchange was then carried out keeping the silicone tipped back-flush cannula just medial to the free edge of the inverted flap thus preventing the displacement of the inverted ILM from the optic disc. Finally, intravitreal air was exchanged with non-expansile concentration (14%) of octafluoropropane (C3F8). At the end surgery, the patient was discharged with instruction to lie face down for 1 week, postoperatively.

Figure 2.

(a) In this intra-operative view, schematically drawn, black arrow indicates the site and direction for initiation, and magenta-pink arrows indicate the direction for progression of internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling. ILM peeling ends at the green arrowhead, leaving an area where the peeled ILM is left with an attachment acting as a pedicle. (b) Intraoperative photo. ILM is peeled off from macular area but partly left attached with a stalk. (c) Schematic drawing demonstrating the peeled ILM attached with a pedicle but now inverted on the optic disc. The dotted line indicates the area from where the ILM is peeled. (d) Surgeon's view intraoperatively. Peeled ILM is inverted and lying on the optic disc

The patient was examined on the first postoperative day, at 7 days, 2 weeks, monthly intervals for the next 3 months; and then at 3-month intervals. Examinations at every visit included visual acuity, anterior segment assessment, measurement of IOP, and clinical evaluation of the posterior segment. OCT examination of the optic nerve and macula were performed once the gas bubble cleared the macular area when the patient was sitting.

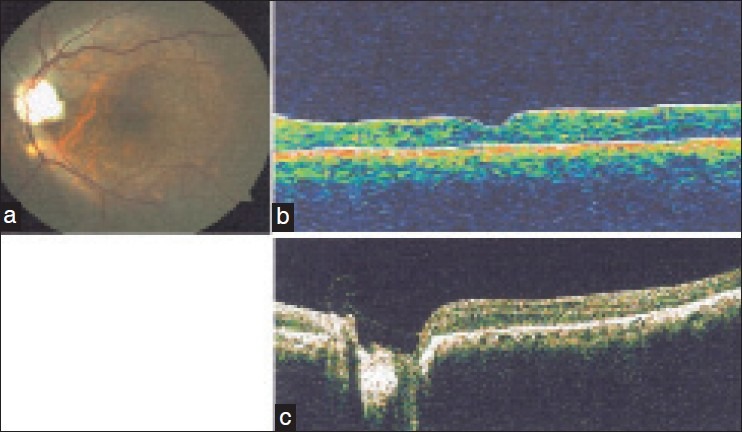

The macular detachment regressed completely at 1 month [Figures 3a and b]. Postoperatively, the best corrected visual acuity improved to 6/24 at one month and to 6/12 at 3 months, which was maintained out to10 months (last visit to date). Although it was clinically difficult to assess the newly relocated ILM, the postoperative OCT examination confirmed coverage of optic pit by the inverted ILM [Figure 3c].

Figure 3.

(a) Postoperative fundus photo with regressed macular detachment. (b) Postoperative optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirming flat macula. (c) Postoperative OCT confirming presence of inverted internal limiting membrane covering the optic disc pit

DISCUSSION

Optic disc pits are congenital excavations of the optic nerve head. Histologically, optic disc pits are defects in the lamina cribrosa.[2,3] Visual acuity gets affected when the pit is complicated by serous macular retinal detachment.

The unfavorable natural history of this pathology has encouraged ophthalmologists to use one procedure or a combination of techniques as warranted. Common procedures include laser photocoagulation to the temporal margin of the optic disc, pars plana vitrectomy, internal tamponade, and internal drainage of submacular fluid. However, the optimal treatment is controversial. This is because the pathophysiology of macular detachment in optic disc pit remains unclear. Four possible sources of this fluid have been proposed: Fluid from the vitreous cavity, cerebrospinal fluid originating from the subarachnoid space, fluid from leaky blood vessels at the base of the pit, and fluid from the orbital space surrounding the dura.[1]

Laser photocoagulation alone to the temporal margin of the disc does not generally yield promising results. Possible side effects of laser photocoagulation near the disc include paracentral scotomas, no change in visual acuity, and a low success rate in the resolution of serous macular detachment.[4]

Tangential vitreous traction is also thought to be important in the pathogenesis of optic disc pits. Vitrectomy with removal of posterior hyaloid alone combined with C3F8gas and laser treatment to the temporal edge of optic disc has been successfully used to reattach the macula.[5] The viscous nature of the fluid has prompted some surgeons to attempt active internal drainage of subretinal fluid, intraoperatively.[6]

There have been reports of using fibrin glue to close the optic nerve pit when it is associated with serous macular detachment. Kumar et al., have used Tisseel VH fibrin sealant (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Westlake Village, CA, USA) intraoperatively in the management of optic disc pit-associated macular detachments.[7] The technique involved pars plana vitrectomy, removal of posterior hyaloid, fluid-air exchange, drainage of subretinal fluid through optic disc pit, application of the fibrin sealant to the pit and air–C3F8gas exchange and postoperative prone positioning.[7,8]

However, autologous tissue such the patient's ILM is more physiological to seal the congenital defect in the lamina cribrosa. We believe that this technique of placing the autologous ILM in front of the optic nerve pit will create a permanent barrier thus preventing the flow of fluid through the pit. This new barrier may also prevent the migration of silicone oil into the subretinal space which may otherwise occur in some patients as reported by Prahs et al.,[9] and Behct et al.,[10] Since, intraoperative laser photocoagulation to the temporal edge of the optic disc may cause more damage we did not apply endolaser in this case. Additionally, we did not perform endo-drainage.

Obtaining the ILM as a single sheet with its pedicle still attached can be quite challenging technically, but staining the ILM with brilliant blue dye helped in creating a large ILM flap. To keep the inverted ILM flap apposed to the optic disc, we suggest placing a small bubble of heavy liquid (e.g. perfluoro decalin) over the inverted ILM flap lying on the optic disc prior to fluid-air exchange. Postoperative displacement of the ILM from the optic disc with the pit is also possibility. However, leaving an area where the peeled ILM is still attached with a pedicle (or the stalk) and postoperative face-down positioning ensures that the ILM remains apposed to the new location.

To summarize, this is a new surgical technique which was employed for an optic nerve pit complicated by serous macular detachment in a female patient. Pars plana vitrectomy was performed along-with ILM peeling and then the peeled ILM was inverted and used to close the optic nerve pit. This technique resulted in a satisfactory anatomic outcome with good functional improvement in the visual acuity. This technique needs further evaluation in a larger cohort of similar patients, because similar satisfactory anatomic outcomes with improvement in the visual acuity can be achieved by the standard pars plana vitrectomy with fluid-air-gas exchange. However, due to the rare occurrence congenital optic disc pit associated with macular involvement, conducting a study with a large case-series remains a challenge.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Georgalas I, Ladas I, Georgopoulos G, Petrou P. Optic disc pit: A review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1113–22. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1698-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kranenburg EW. Crater-like holes in the optic disc and central serous retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1960;64:912–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1960.01840010914013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song IS, Shin JW, Shin YW, Uhm KB. Optic disc pit with peripapillary retinoschisis presenting as a localized retinal nerve fiber layer defect. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011;25:455–8. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2011.25.6.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diab F, Al-Sabah K, Al-Mujaini A. Successful surgical management of optic disc pit maculopathy without internal membrane peeling. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010;17:278–80. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.65495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziahosseini K, Sanghvi C, Muzaffar W, Stanga PE. Successful surgical treatment of optic disc pit maculopathy. Eye. 2009;23:1477–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaal KB, Wrede J, Dithmar S. Internal drainage in optic pit maculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1093. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.110304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar N, Al Sabti K. Fibrin glue in ophthalmology. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58:176. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.60093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar N, Al Sabti K. Optic disc pit maculopathy treated with vitrectomy, internal limiting membrane peeling, and gas tamponade: A report of two cases. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:897. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prahs PM, Valmaggia C, Helbig H. Subretinal silicone oil and perfluorocarbon in a patient with an optic disc pit. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2010;227:191–3. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1245270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becht C, Senn P, Lange AP. Delayed occurrence of subretinal silicone oil after retinal detachment surgery in an optic disc pit-a case report. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2009;226:357–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]