Abstract

Context

In humans, sleep duration often determines the night (dark) length experienced, because we close our eyes when we sleep and are exposed to artificial or natural light when we are awake. Although it is recognized that there is an increasing trend in modern society toward shorter sleep time, it is not known how short nights (long photoperiods) affect the human circadian system.

Objective

In this study we investigated for the first time the effects of night length on circadian phase shifts to light in humans.

Design and Setting

Eight young healthy subjects experienced 2 wk of 6-h sleep episodes in the dark (short nights) and 2 wk of long 9-h sleep episodes (long nights) in counterbalanced order. After each series of nights, they were exposed to four 30-min pulses of morning bright light (~5000 lux) that advanced by 1 h/d for 3 consecutive days while night (dark) length was maintained at 6 or 9 h. Circadian phase was determined from the circadian rhythm of melatonin in dim light before and after the 3-d bright light treatments.

Results

The phase advance in the melatonin rhythm during the short nights was less than half of that observed during the long nights (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

This result shows for the first time that people who curtail their sleep may unwittingly reduce their circadian responsiveness to morning light. This finding also demonstrates that sleep length can alter human circadian function and has important implications for enhancing the treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders.

The mammalian circadian clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (1), generates circadian rhythms with an endogenous period slightly greater than 24 h (2–4) and is entrained to the 24-h day by daily exposure to morning light. As illustrated by the human phase response curve to light, light in the morning causes circadian rhythms to shift earlier in time (phase advance), and light in the evening causes circadian rhythms to shift later in time (phase delay). The crossover time between delays and advances is near the core body temperature minimum (5–7). Importantly, studies in mammals have shown that photoperiod can greatly impact the effect of light on the circadian clock. The phase response curve to light in Syrian hamsters is significantly reduced in both amplitude and range after long photoperiods (short nights) (8), and light-induced phase shifts in hamster and mouse wheel-running activity (9, 10) and in the rat pineal N-acetyltransferase rhythm (11) are significantly attenuated after long photoperiods (short nights).

In humans, sleep duration often determines the night length experienced, because we sleep with our eyes closed and are usually exposed to artificial or natural light when awake. Furthermore, due to an increasing trend toward short sleep episodes, humans in modern society are increasingly experiencing long photoperiods (short nights). Thirty-one percent of recently surveyed Americans reported regularly sleeping 6 h or less each weeknight, and 17% reported sleeping 6 h or less per night on the weekend (12). In this study we present results that demonstrate for the first time that short nocturnal sleep episodes in humans, which create a perceived long photoperiod, reduce circadian phase shifts to light.

Subjects and Methods

Eight healthy volunteers (five men and three women; mean age, 28.1 yr; mean body mass index, 24.1 kg/m2) participated. All subjects were nonsmokers, were medication free, consumed only moderate caffeine doses (<300 mg/d), and reported no medical, psychiatric, or sleep disorders, as assessed from in-person interviews and questionnaires. A urine drug screen confirmed that they were all free of common drugs of abuse. No subject had worked night shifts or traveled overseas in the previous month. The self-reported mean weekday sleep schedule in the week before the study was 0050 ± 1.2 to 0757 ± 1.0 h. The protocol was approved by the Rush University Medical Center institutional review board and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave written informed consent before participation.

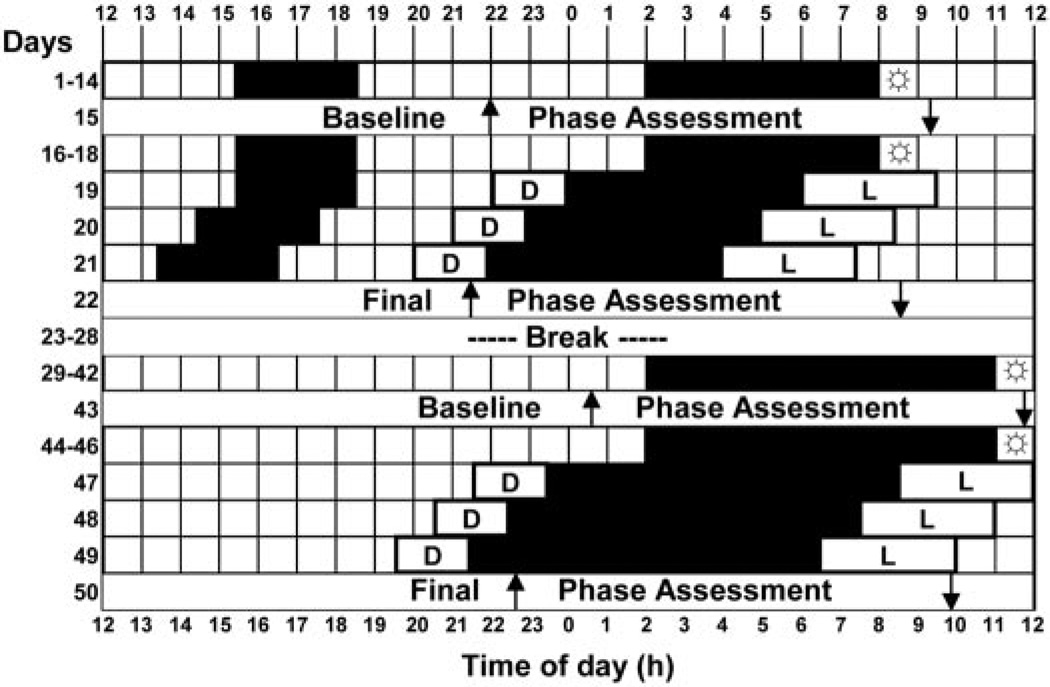

Each subject experienced 14 6-h nights and 14 9-h nights (Fig. 1). Each series of nights was followed by a phase assessment, 3 more days on 6- or 9-h nights, a 3-d advancing bright light stimulus, and then another phase assessment. There was a 6-d break between the short and long nights during which subjects returned to their prestudy sleep times. Three subjects completed the short nights first, and five subjects completed the long nights first. During the short nights, subjects woke at their habitual weekday wake time and went to bed 6 h before wake time. During the long nights, subjects woke 3 h later than their habitual weekday wake time and went to bed at the same time as in the short nights. To avoid excessive sleep deprivation during the short nights, napping was permitted within a 3-h window, centered 12 h from the midpoint of the nighttime dark period, when neither light nor dark phase shift circadian rhythms (13, 14).

Fig. 1.

An experimental protocol for an individual who experienced the short nights first. Black shading shows sleep/dark episodes at night and optional nap zone during the day during the short nights. L, Advancing bright light stimulus: four 30-min bright light pulses alternating with ordinary room light, starting 8 h after the baseline DLMO, and advancing by 1 h/d; D, dim light (<60 lux) in the laboratory; ↑, time of DLMO; ↓, time of DLMOff. The sunbursts indicate 10 min of outdoor light. For clarity, the phase assessments are shown as starting and ending at 1200 h.

All subjects slept alone at home except during the3dof the advancing bright light stimulus, when they slept in the laboratory. At home they slept in darkened bedrooms (<1 lux; bedroom windows were covered with black plastic), and the laboratory bedrooms were also completely dark. The subjects were required to go outside to receive a minimum of 10 min of light in the first 1.5 h after their scheduled wake time. To ensure compliance to the scheduled sleep/dark episodes and light requirement, subjects wore an actigraph on their wrist and a photosensor around their necks (Actiwatch-L, Mini-Mitter, Bend, OR) during the entire study, and data from these monitors were inspected every 1–3 d. Subjects also completed daily sleep logs that were verified with the wrist actigraphy.

Each subject experienced four phase assessments (Fig. 1). The phase assessments were 20–24 h long and began between 1200–1800 h. During the phase assessments, subjects remained awake and seated in recliners in dim light (<5 lux, at the level of the subjects’ eyes, in the direction of gaze; TL-1 light meter, Minolta, Ramsey, NJ). Subjects gave a 2-ml saliva sample every 30 min (using Salivettes, Sarstedt, Newton, NC), which were later radioimmunoassayed (single samples) for melatonin by Pharmasan Laboratories (Osceola, WI). The sensitivity of the assay was 0.7 pg/ml, and intra- and interassay coefficients of variabilities were 12.1% and 13.2%, respectively. Melatonin is a hormone synthesized and released from the pineal gland (15) and in dim light is a reliable marker of the circadian clock (16, 17). Three phase markers were derived from each melatonin profile: dim light melatonin onset (DLMO), dim light melatonin offset (DLMOff), and the midpoint, halfway in time between the DLMO and DLMOff. For each subject’s melatonin profile, a threshold was calculated as the mean of the first three low daytime values plus twice the sd (18). Each subject’s DLMO was the point in time (as determined with linear interpolation) when the melatonin concentration exceeded the threshold. The DLMOff was the point in time when melatonin levels fell below the threshold. The mean ± sd threshold was 1.6 ± 0.7 pg/ml.

On the first night of the advancing bright light stimulus, subjects were awakened 8 h after their baseline DLMO and were put to bed in a dark, individual, temperature-controlled bedroom, either 6 or 9 h earlier, depending on the condition. Subjects arrived at the laboratory 2 h before bedtime. On awakening, they experienced 3.5 h of bright intermittent light (mean intensity, 5064 ± 807 lux; 30 min alternating with 30 min room light <350 lux, measured periodically at angle of gaze; 401025 light meter, Extech, Waltham, MA). The bright light was produced by a single light box (61 × 61 × 10 cm; Enviro-Med, Vancouver, WA) placed on a desk, about 40 cm in front of the subject’s eyes. Each light box had a diffuser screen and contained four 54-cm-long, 40-watt fluorescent horizontal tubes (PL-L40W/41/RS/IS, 4100K, Philips Electronic Instruments, Mahway, NJ). The room light was produced by a ceiling fixture containing three fluorescent tubes. On the second and third nights of the bright light stimulus, subjects experienced the same procedure, except the timing of their sleep and bright light exposure was advanced by 1 h/d (Fig. 1). After each 3-d advancing bright light stimulus, subjects experienced another phase assessment.

Results

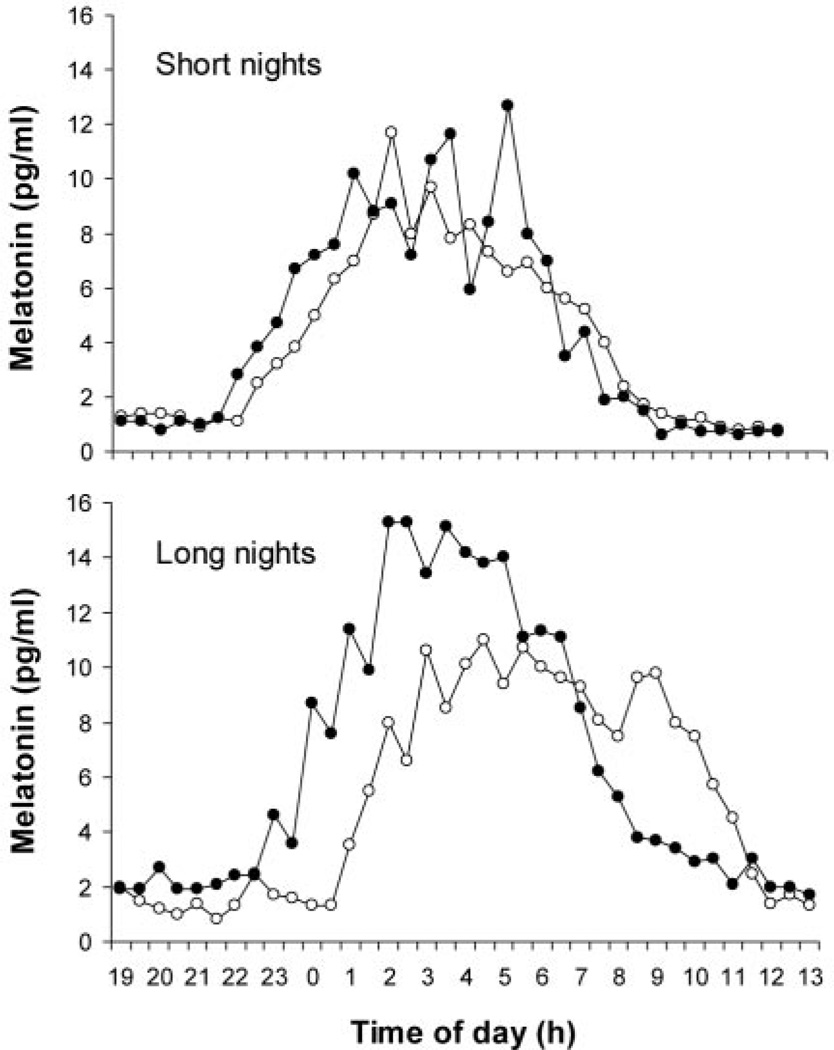

Dim light melatonin profiles from each of the four phase assessments for an individual subject are shown in Fig. 2. The melatonin rhythm phase advanced in response to the bright light stimulus during both short and long nights, but the advance was markedly attenuated during the short nights. The same pattern can be seen in the average phase advances of all eight subjects (Fig. 3). A two-way multivariate ANOVA with one within-subjects factor, NIGHT (short vs. long), and one between-subjects factor, ORDER (short nights first vs. long nights first), revealed only a main effect for NIGHT. There was no significant main effect for ORDER, nor any significant interaction between ORDER and NIGHT (P < 0.10). Examination of univariate results indicated that all three phase markers phase advanced significantly less during the short nights (DLMO, P = 0.003; midpoint, P = 0.001; DLMOff, P = 0.012). As expected, the actigraphy-verified sleep logs showed that the average hours of sleep per day (nighttime sleep plus naps) was significantly shorter in the short nights than in the long nights (6.6 ± 0.5 vs. 8.0 ± 0.7 h; by paired t test, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

An individual’s melatonin profiles during the baseline (○) and final phase assessment (●) during the short and long nights. The protocol for this individual is shown in Fig. 1. The DLMO advanced only 0.5 h during the short nights, but 2.0 h during the long nights. The DLMOff advanced only 0.8 h during the short nights, but 1.9 h during the long nights.

Fig. 3.

The mean phase advances observed in DLMO, midpoint, and DLMOff due to the advancing bright light stimulus during the long nights (■) and the short nights (□). Error bars represent the SEM. There was at least a 2-fold reduction in the phase advance in all three circadian phase markers during the short nights compared with that during the long nights.

Discussion

This study is the first to show that in humans, circadian phase advances in response to morning light markedly decrease with short nights. These results cannot be due to differences in the timing of the bright light stimulus between the two conditions, because subjects were exposed to the bright light at the same circadian phase, 8 h after the baseline DLMO (~1 h after the temperature minimum) (19–21), at a time that produces large phase advances. Instead, there are four possible factors that may have contributed to the results: 1) the photoperiodic history of short nights may have reduced the range and amplitude of the light phase response curve, as previously seen in Syrian hamsters (8); 2) the sleep deprivation associated with the short nights may have reduced the phase shift to light, as previously seen in Syrian hamsters and mice, possibly due to alterations in serotonergic activity (22, 23); 3) the increased exposure to ambient light during the 3 wk of short nights (up to 3 h/d) may have reduced the subjects’ photosensitivity (24, 25); or 4) the additional 3 h of evening light during the 3 d of the advancing stimulus with short nights (ending 2 h after the baseline DLMO on the first night of the advancing stimulus) may have produced a phase delay, thereby partially counteracting the phase advancing stimulus. Given these four possibilities, the first two (photoperiodic history and sleep deprivation) are the most likely causes. The third explanation is doubtful, because 3 additional hours of dim evening light per night is unlikely to significantly alter light sensitivity. Indeed, it has previously been shown that approximately 4 h of bright light/d for 1 wk compared with 1 wk with no bright light only moderately reduced melatonin suppression to light (24). The fourth explanation is also improbable, because repeated exposure to dim evening light only slightly phase delayed the circadian clock (~0.6 h) (26), and so it is unlikely that the dim evening light could diminish the phase advance due to morning light by approximately 1.4 h.

Our results clearly demonstrate that when people curtail their sleep, thus creating a long perceived photoperiod, they phase advance less in response to morning light. These results readily generalize to modern society in three ways. Our protocol with 6- and 9-h night lengths represents realistic variations in sleep length. Additionally, longer nights are often due to later wake times, as in our protocol. Finally, our subjects regularly experienced 10 min of sunlight every morning, similar to the morning light exposure many people receive every day. An attenuation in light-induced circadian phase advances during short nights has serious implications for the sleep-deprived general population, jet travelers, and patients with delayed sleep phase syndrome. Experimental studies have shown that the human circadian clock already phase shifts quite slowly in response to bright light, typically advancing less than 2.0 h/d (5, 27). Because the endogenous period of the circadian clock is, on the average, slightly greater than 24 h (2–4), most of us require small daily phase advances to remain entrained to the 24-h day, and larger phase advances when late nights (26) or late wake times (28) cause the circadian clock to phase delay even further. Jet travelers who travel east also require phase advances to entrain to destination time as quickly as possible, thereby minimizing jet lag (29). Patients with delayed sleep phase syndrome require phase advances so that they can sleep and wake at socially acceptable times (30). In all of these cases, our results suggest that the phase advances necessary for optimal circadian entrainment to the environment will occur at a greatly reduced rate if people truncate their sleep. Future research needs to determine how many consecutive short nights are required to observe reduced phase advances to light, whether sleep deprivation in humans reduces circadian phase shifts, and whether phase delays in response to light and phase shifts to exogenous melatonin are also reduced during short nights.

Acknowledgments

We thank Young Cho, Meredith Durkin, Clifford Gazda, Cindy Hiltz, Hyungsoo Kim, Clara Lee, Kathryn Lenz, Tom Molina, Courtney Pearson, and Mark Smith for their assistance with data collection; Dr. Louis Fogg for his statistical advice; and our Medical Director, Keith L. Callahan, M.D. Enviro-Med donated the light boxes.

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Sleep Medicine Foundation, a foundation of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

Abbreviations

- DLMO

Dim light melatonin onset

- DLMOff

dim light melatonin offset

References

- 1.Moore RY. Organization and function of a central nervous system circadian oscillator: the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Fed Proc. 1983;42:2783–2789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, Brown EN, Mitchell JF, Rimmer DW, Ronda JM, Silva EJ, Allan JS, Emens JS, Dijk DJ, Kronauer RE. Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science. 1999;284:2177–2181. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sack RL, Lewy AJ, Blood ML, Keith LD, Nakagawa H. Circadian rhythm abnormalities in totally blind people: Incidence and clinical significance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:127–134. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.1.1619000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wever RA. The circadian system of man. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eastman CI, Martin SK. How to use light and dark to produce circadian adaptation to night shift work. Ann Med. 1999;31:87–98. doi: 10.3109/07853899908998783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czeisler CA, Kronauer RE, Allan JS, Duffy JF, Jewett ME, Brown EN, Ronda JM. Bright light induction of strong type 0 resetting of the human circadian pacemaker. Science. 1989;244:1328–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.2734611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minors DS, Waterhouse JM, Wirz-Justice A. A human phase-response curve to light. Neurosci Lett. 1991;133:36–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90051-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittendrigh CS, Elliott J, Takamura T. The circadian component in photoperiodic induction. Ciba Found Symp. 1984;104:26–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans JA, Elliott JA, Gorman MR. Photoperiod differentially modulates photic and nonphotic phase response curves of hamsters. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:R539–R546. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00456.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Refinetti R. Compression and expansion of circadian rhythm in mice under long and short photoperiods. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 2002;37:114–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02688824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Illnerova H, Vanecek J. Entrainment of the circadian rhythm in rat pineal N-acetyltransferase activity under extremely long and short photoperiods. J Pineal Res. 1985;2:67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1985.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Sleep Foundation. Less fun, less sleep, more work: an American portrait. 2001 www.sleepfoundation.org/publications/2001poll.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buxton OM, L’Hermite-Baleriaux M, Turek FW, Van Cauter E. Daytime naps in darkness phase shift the human circadian rhythms of melatonin and thyrotropin secretion. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:R373–R382. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.2.R373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumont M, Carrier J. Daytime sleep propensity after moderate circadian phase shifts induced with bright light exposure. Sleep. 1997;20:11–17. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore RY. The innervation of the mammalian pineal gland. Prog Reprod Biol. 1978;4:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klerman EB, Gershengorn HB, Duffy JF, Kronauer RE. Comparisons of the variability of three markers of the human circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17:181–193. doi: 10.1177/074873002129002474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewy AJ, Cutler NL, Sack RL. The endogenous melatonin profile as a marker of circadian phase position. J Biol Rhythms. 1999;14:227–236. doi: 10.1177/074873099129000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voultsios A, Kennaway DJ, Dawson D. Salivary melatonin as a circadian phase marker: validation and comparison to plasma melatonin. J Biol Rhythms. 1997;12:457–466. doi: 10.1177/074873049701200507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eastman CI, Martin SK, Hebert SK. Failure of extraocular light to facilitate circadian rhythm reentrainment in humans. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:807–826. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100102116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown EN, Choe Y, Shanahan TL, Czeisler CA. A mathematical model of diurnal variations in human plasma melatonin levels. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E506–E516. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.3.E506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cagnacci A, Soldani R, Laughlin GA, Yen SSC. Modification of circadian body temperature rhythm during the luteal menstrual phase: role of melatonin. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:25–29. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mistlberger RE, Landry GL, Marchant EG. Sleep deprivation can attenuate light-induced phase shifts of circadian rhythms in hamsters. Neurosci Lett. 1997;238:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Challet E, Turek FW, Laute M, Van Reeth O. Sleep deprivation decreases phase-shift responses of circadian rhythms to light in the mouse: role of serotonergic and metabolic signals. Brain Res. 2001;909:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02625-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hebert M, Martin SK, Lee C, Eastman CI. The effects of prior light history on the suppression of melatonin by light in humans. J Pineal Res. 2002;33:198–203. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.01885.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith KA, Schoen MW, Czeisler CA. Adaptation of human pineal melatonin suppression by recent photic history. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3610–3614. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgess HJ, Eastman CI. Early versus late bedtimes phase shift the human dim light melatonin rhythm despite a fixed morning lights on time. Neurosci Lett. 2004;356:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanahan TL, Kronauer RE, Duffy JF, Williams GH, Czeisler CA. Melatonin rhythm observed throughout a three-cycle bright-light stimulus designed to reset the human circadian pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms. 1999;14:237–253. doi: 10.1177/074873099129000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang CM, Spielman AJ, D’Ambrosio P, Serizawa S, Nunes J, Birnbaum J. A single dose of melatonin prevents the phase delay associated with a delayed weekend sleep pattern. Sleep. 2001;24:272–281. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgess HJ, Crowley SJ, Gazda CJ, Fogg LF, Eastman CI. Preflight adjustment to eastward travel: 3 days of advancing sleep with and without morning bright light. J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18:318–328. doi: 10.1177/0748730403253585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt JK. Delayed sleep phase syndrome: Pathophysiology and treatment options. Sleep. 2004;27:1195–1203. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.6.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]