Abstract

The performance of two APHA standard laboratory methods, the R2A spread plate and the SimPlate™ for heterotrophic plate count (HPC), for quantifying heterotrophic microorganisms in dental waterline samples was evaluated. Microbial counts were underestimated on SimPlate™ compared with R2A and the results indicated a poor correlation between the two methods.

Keywords: Dental unit waterlines, Dental unit waterline contamination, Dental unit waterline monitoring

Waterlines in functioning dental units have been shown to contain bacterial biofilms up to 50 microns thick, comprised of a heterogeneous population of microorganisms (Porteous et al., 2011; Szymanska 2007). Although bacterial biofilms remain fixed to the tubing wall, microbes are continuously sloughed off as the water flows through, causing contamination of the patient treatment water (Cunningham et al., 2011; Lenz et al., 2008).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that dental offices should ensure that the level of non-coliform bacteria in patient treatment water meets the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) drinking water standard of <500 colony forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) (U.S. EPA 1999; CDC 2003). Dental practitioners are encouraged to monitor the level of dental unit waterline (DUWL) contamination regularly in order to comply with this recommendation. Monitoring DUWL quality can be done by using in-office chairside kits or by using a mail-in service provided by commercial laboratories.

Standard laboratory testing methods have been established by The American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, and The Water Environment Federation (APHA et al., 2012). Four different methods (9215B-9215E) and five different types of media are recommended for use with specific applications. Each method is designed to provide the heterotrophic plate count (HPC), an estimate of the number of live heterotrophic bacteria in water samples. The use of low-nutrient media such as R2A agar (Beckton, Dickson and Company, Sparks, MD) is considered best suited to the cultivation of a variety of slow-growing, indigenous water organisms (Reasoner 2004). The spread plate method (9215C), using R2A agar allows microbial colonies to grow on the agar surface at 20 to 28°C over a period of 7 days. The limitation of this method is that it relies on a small volume of water sample, which can be absorbed if the agar is dry (APHA et al., 2012). However, this is generally accepted as the most appropriate method for culturing organisms from DUWL samples (Bartoloni et al., 2006).

This most recent addition to the list of standard methods is 9215E, the SimPlate™ for HPC (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME). It is a less tedious method than 9215C that merely involves mixing the water sample with a proprietary substrate and as microbial enzymes metabolize the substrate, they fluoresce after 48 hours of incubation at 35°C (APHA et al., 2012). The number of fluorescent wells are counted and converted to the most probable number (MPN), using a table provided by the manufacturers (Stillings et al., 1998). As this method becomes more widely used, dental offices may be obtaining results from commercial laboratories that use this method rather than Method 9215C. The purpose of this experiment was to compare Method 9215C and 9215E for culturing DUWL samples.

An a priori power analysis, performed using PASS 11 software (NCSS Inc., Kaysville, UT), was first conducted to determine sample size. Fifteen functioning dental units in a teaching clinic were randomly selected from 300 dental operatories and water samples were taken from the handpiece and air/water syringe lines on each unit, and from the source faucet water in each operatory. One-hundred mL sterile collection bottles that contained sodium thiosulfate to neutralize residual chlorine (IDEXX Labs, Westbrook, ME) were used to collect a total of 45 samples. Ten-fold serial dilutions of each sample were made with phosphate buffer solution.

For the R2A cultures, 0.1mL of each solution was spread on R2A plates in triplicate, incubated at room temperature, and the microbial CFU/mL was recorded after 7 days (APHA, Method 9215C). For the SimPlate™ cultures, 10 mL of each solution were placed in the center of the SimPlates™ and manufacturers’ instructions were followed. Plates were incubated for 48 hrs at 35°C (Jackson et al., 2000) and the MPN/mL was calculated.

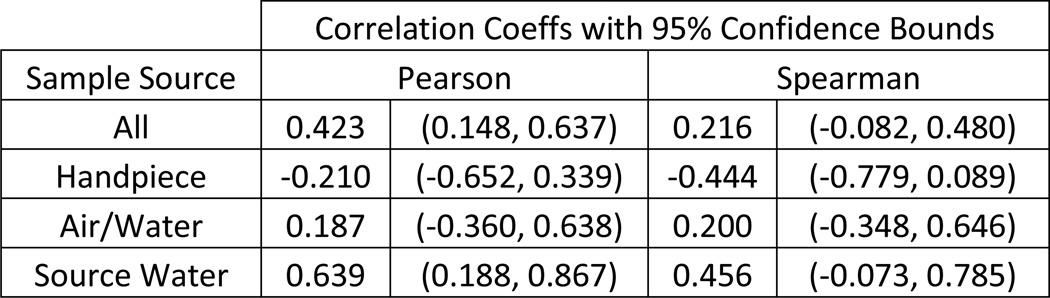

Statistical analyses and graphics were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Microbial counts for each of the methods are provided in Table 1. As expected, the R2A measures approximated an exponential distribution; however, the SimPlate™ for HPC values approximated a uniform distribution between 0 and an upper threshold value of >73.8 MPN/mL, so correlations were performed instead of paired Student’s t-test using log transformed R2A measures and raw HPC values. The overall Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.423 with 95% c.i. of (0.148, 0.637) was weak, while the corresponding Spearman rank correlation coefficient of 0.216 with 95% c.i. of (−0.082, 0.480) was poorer, which suggested that the Pearson correlation was influenced by extreme values. Correlations for each source type were also performed (Figure 1) with similar results.

TABLE 1.

Number of colony forming units/per milliliter (CFU/mL) and Most Probable Number/milliliter (MPN/mL) obtained from handpiece lines, air/water syringes and source water for each dental unit.

| Dental Unit | Sample Source | CFU/mL (R2A) | MPN/mL(SimPlate™) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Handpiece | 10,967 | 19.5 |

| Air/Water | 275,333 | *74.0 | |

| SourceWater | 11,500 | 47.0 | |

| 2 | Handpiece | 17,733 | 62.3 |

| Air/Water | 11,033 | 50.7 | |

| SourceWater | 2,800 | 27.6 | |

| 3 | Handpiece | 48,333 | 20.9 |

| Air/Water | 146,333 | 47.0 | |

| SourceWater | 7,867 | 44.0 | |

| 4 | Handpiece | 35,000 | 44.0 |

| Air/Water | 682,667 | 32.4 | |

| SourceWater | 13,967 | *74.0 | |

| 5 | Handpiece | 94,000 | 31.1 |

| Air/Water | 424,667 | 37.2 | |

| SourceWater | 513 | 0.2 | |

| 6 | Handpiece | 372,000 | *74.0 |

| Air/Water | 419,333 | 44.0 | |

| SourceWater | 2,240 | 39.2 | |

| 7 | Handpiece | 126,000 | 50.7 |

| Air/Water | 124,000 | 47.0 | |

| SourceWater | 8,400 | *74.0 | |

| 8 | Handpiece | 110,667 | 62.3 |

| Air/Water | 94,000 | 50.7 | |

| SourceWater | 32,333 | *74.0 | |

| 9 | Handpiece | 22,500 | *74.0 |

| Air/Water | 130,667 | 44.0 | |

| SourceWater | 42,000 | 35.5 | |

| 10 | Handpiece | 162,000 | *74.0 |

| Air/Water | 107,667 | *74.0 | |

| SourceWater | 70 | 0.4 | |

| 11 | Handpiece | 117,000 | 44.0 |

| Air/Water | 30,333 | 29.9 | |

| SourceWater | 51,667 | 22.3 | |

| 12 | Handpiece | 703,333 | 27.6 |

| Air/Water | 633,333 | 22.3 | |

| SourceWater | 107 | 3.5 | |

| 13 | Handpiece | 165,000 | 32.4 |

| Air/Water | 121,333 | 50.7 | |

| SourceWater | 50,333 | 26.6 | |

| 14 | Handpiece | 213,333 | 62.3 |

| Air/Water | 134,333 | 28.7 | |

| SourceWater | 13,767 | 47.0 | |

| 15 | Handpiece | 822,000 | 62.3 |

| Air/Water | 182,333 | 37.2 | |

| SourceWater | 1,783 | 25.7 |

MPN of >73.8/mL

Figure 1.

Correlations between R2A spread plate and SimPlate™ for HPC values.

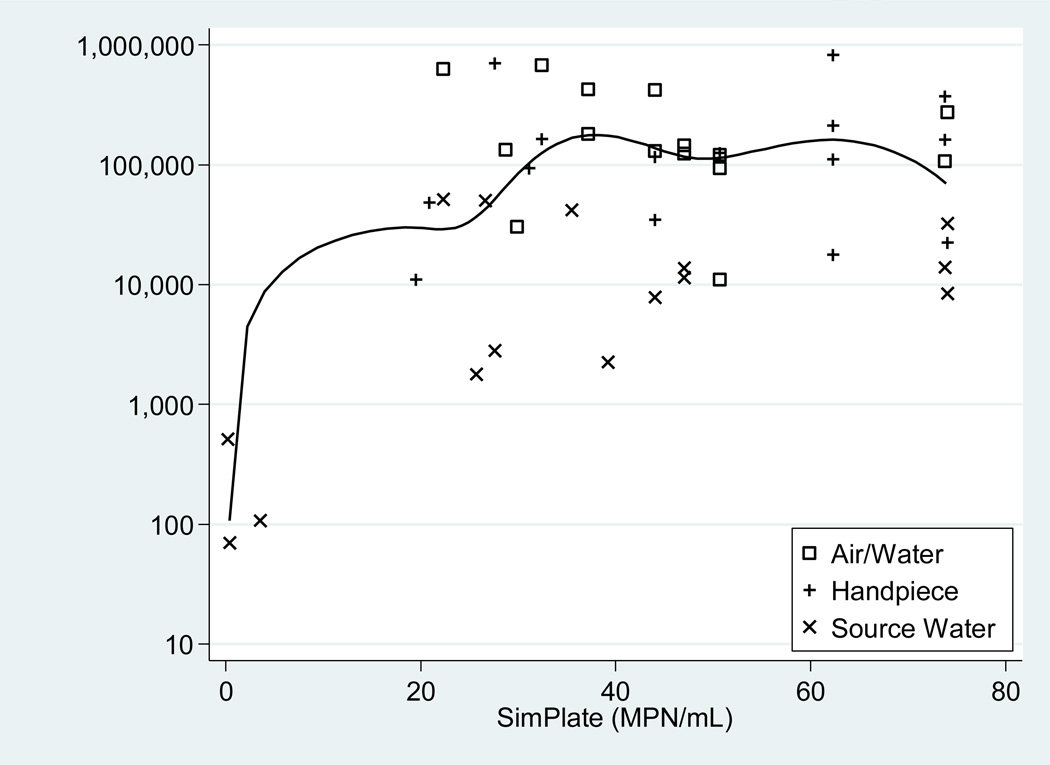

To depict the pairwise association, a scatterplot (Figure 2), displaying the paired results for each sample with symbols indicating the source type, illustrates the extreme values that inflated the Pearson coefficient relative to the Spearman coefficient were three source water samples with virtually undetectable contamination.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of SimPlate™ (MPN/mL) values matched with R2A (CFU/mL) values. A log base 10 transformation was applied to the R2A (vertical) axis. A median spline curve was used to illustrate the correlation between the SimPlate™ and R2A values.

A previous study showed that the SimPlate™ for HPC method produced similar results to the pour plate 9215 B method that uses the less sensitive plate count agar and incubation at 35°C, but lower counts than the membrane filter R2A method (9215D) that uses room temperature incubation for 7 days (Stillings et al., 1998). Our study showed similar results. Furthermore, many of our undiluted samples resulted in the maximum number of fluorescent wells, corresponding to a MPN of >73.8/mL; yet, ten-fold dilutions did not provide the expected results with the majority of those showing zero fluorescent wells.

In summary, the SimPlate™ for HPC method failed to detect microbial levels in DUWL samples to the same extent as the R2A spread plate method. Due to potential undesirable consequences of DUWL contamination for dental personnel and patients regular monitoring and accurate assessment of DUWL quality is essential (Atlas 1995; Ricci 2012; CDC 2003). As some dental offices rely on commercial laboratories to provide this service, it is recommended that the R2A spread plate 9215C method be used for analyzing DUWL samples. Other findings of note in this study, such as the high microbial levels found in the source water and DUWL samples should be further investigated.

Acknowledgement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Dental & CraniofacialResearch of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 DE018707-05. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Public Health Association. American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation. In: Rice EW, Baird RB, Eaton AD, Clesceri LS, editors. Microbiological Examination. 22nd ed. Washington: Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater; 2012. pp. 9.49–9.52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas RM, Williams JF, Huntingdon MK. Legionella contamination of dental unit waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1208–1213. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1208-1213.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartoloni JA, Porteous NB, Zarzabal LE. Measuring the validity of two in-office water test kits. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(3):363–371. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings – 2003. MMWR. 2003;52((RR17)) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham AB, Lennox JE, Ross RJ, editors. Biofilms:The Hypertextbook. 2011. Biofilm growth and development. Retreived from http://www.biofilmbook.com. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson RW, Osborne K, Barnes G, Jolliff C, Zamani D, Roll B, et al. Multiregional Evaluation of the SimPlate Heterotrophic Plate Count Method Compared to the Standard Plate Count Agar Pour Plate Method in Water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(1):453–454. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.453-454.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenz AP, Williamson K, Pitts B, Stewart PS, Franklin MJ. Localized gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(14):4463–4471. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00710-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porteous NB, Luo J, Schoolfield J, Sun Y. The biofilm-controlling functions of rechargeable antimicrobial N-halamine dental unit waterline tubing. J Clin Dent. 2011;22(5):163–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reasoner DJ. Heterotrophic plate count methodology in the United States. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;92:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricci ML, Fontana S, Pinci F, Fiumana E, Pedna MF, Farolfi P, et al. Pneumonia associated with a dental unit waterline. The Lancet. 2012;379:684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stillings A, Herzig D, Roll B. Comparative assessment of the newly-developed SimPlate™ method with the existing EPA-approved Pour Plate method for the detection of heterotrophic plate count bacteria in ozone-treated drinking water; International Ozone Association Conference; 1998. Oct, Retrieved from: www.idexx.com. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szymanska J. Bacterial contamination of water in dental unit reservoirs. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2007;14:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Environmental Protection Agency. Washington DC: US Environmental Protection Agency; 1999. National primary drinking water regulations, 1999: list of contaminants. Retrieved from: http://www.epa.gov/safewater/contaminants/index.html. [Google Scholar]