Abstract

Progranulin is a widely expressed, cysteine-rich, secreted glycoprotein originally discovered for its growth factor–like properties. Its subsequent identification as a causative gene for frontotemporal dementia (FTD), a devastating early-onset neurodegenerative disease, has catalyzed a surge of new discoveries about progranulin’s function in the brain. More recently, progranulin was recognized as an adipokine involved in diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, revealing its metabolic function. Here, we review progranulin biology in both neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases. In particular, we highlight progranulin’s growth factor–like, trophic, and anti-inflammatory properties as potential unifying themes in these seemingly divergent conditions. We also discuss potential therapeutic options for raising progranulin levels to treat progranulin-deficient FTD, as well as the possible consequences of such treatment.

A Progranulin Primer

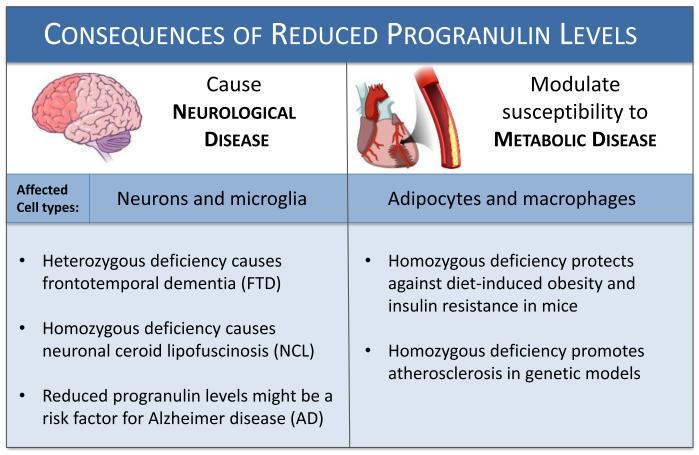

Progranulin is one in a growing list of proteins with roles in both neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases. Deficiency of the secreted protein progranulin in the central nervous system (CNS) causes neurodegeneration: the neurodegenerative disease frontotemporal dementia (FTD, see glossary) with partial progranulin deficiency and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoisis with total deficiency [1]. In peripheral tissues, progranulin excess is linked to obesity and insulin resistance [2, 3] (Figure 1). It is unclear how alterations in progranulin levels result in such diverse disease mechanisms. Progranulin has been linked to angiogenesis, wound repair, cell proliferation, and inflammation [4]. We suggest that the processes necessary for tissue remodeling and injury repair, such as vascularization, cell proliferation, and inflammation, represent a common theme that connects progranulin with neurologic and metabolic diseases. During neurodegeneration, the brain must deal with the burden of neuronal death and cellular debris. Likewise, the progression of obesity, which is central to metabolic diseases, requires continual tissue remodeling as the adipose tissue expands.

Figure 1. Genetic deficiency of progranulin influences neurological and metabolic diseases.

Decreased progranulin levels cause neurodegenerative disease and exacerbate atherosclerosis, yet protect against some aspects of metabolic disease. Patients with loss of function mutations in one progranulin allele develop frontotemporal dementia, while loss of both progranulin alleles leads to neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Further, reduced progranulin levels may also be a risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Conversely, deletion of progranulin in normal mice protects against diet-induced obesity. However, loss of progranulin in mice that lack apo-E promotes the development of atherosclerosis. Thus, loss of progranulin is apparently disease-causing in the brain and has mixed effects on metabolic disease in the periphery. Dysregulation of progranulin-mediated cell growth and inflammation may be involved in the pathogenesis of both subsets of disease.

Here, we review recent studies linking progranulin to neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases. Where appropriate, we speculate on functions of progranulin that might lead to common disease mechanisms. Additionally, we point out the many areas where our knowledge is incomplete and requires further investigation. Essential background information on progranulin is presented in Box 1.

BOX 1. Background on Progranulin.

Progranulin is a secreted, ~80-kDa glycoprotein expressed in many cell types, including epithelial cells, neurons, myeloid cells, immune cells, and adipocytes [83]. Progranulin’s broad expression profile suggests a role in basic cellular functions, such as survival and proliferation. Indeed, it promotes motor neuron survival and neurite outgrowth, tumor cell growth, wound healing, vascularization, and cell migration [42]. Progranulin levels in human and murine plasma are ~200 ng/ml [23, 56] and ~550 ng/ml [45], respectively. In cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), its concentration is much lower: ~6 ng/ml [84, 85] in humans and ~2 ng/ml in mice [86]. Although progranulin is expressed by most neuronal populations in the brain [9, 87], neurons of the frontal and temporal lobes appear to be most sensitive to alterations in its expression, as these are the regions primarily affected in FTD. The expression of progranulin is dramatically upregulated in microglia after injury and during repair [30, 45, 88, 89], underscoring progranulin’s involvement in the inflammatory response. In adipose tissue, progranulin is expressed by both adipocytes and cells of the stromal vascular fraction [3] and acts as an adipokine.

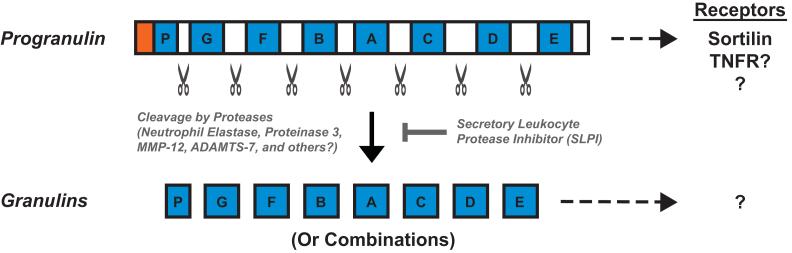

The GRN gene (which encodes progranulin) contains 12 coding exons and is translated into a protein containing 7.5 tandem repeats called granulins (see Figure I). The granulin repeat is structurally defined by the cysteine-rich sequence X2-3CX5-6CX5CCX8CCX6CCXDXXHCCPX4CX5-6CX [90]. The divergent linker sequences that separate granulin repeats can be cleaved by extracellular and intracellular proteases, including neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, ADAMTS-7, and matrix metallopeptidase 12 (MMP-12), to release individual ~6-kDa granulins or, possibly, linked combinations of granulins [91]. Progranulin lacks clear consensus sequences for protease cleavage, suggesting a susceptibility to cleavage by multiple proteases.

Unraveling the relative functions of progranulin and granulins has so far been challenging, and most studies have not addressed this distinction. Is progranulin the main actor, or a precursor protein for potent granulin peptides? Both full-length progranulin and individual granulins exist in vivo [4] and are anti-inflammatory [13] and pro-inflammatory, respectively, suggesting opposing functions [90]. The processing of progranulin to granulins resembles that of prosaposin and saposins. Saposins are 8–11 kDa polypeptides that activate lysosomal enzymes, and are processed from the precursor prosaposin [42]. Although the absence of granulin-specific reagents has limited our understanding of the biological significance of progranulin cleavage, new techniques that make tissue-specific profiling of granulin species possible [92] will shed light on their functional importance.

Progranulin Modulates Growth Factor Signaling

In the 1990s, high levels of progranulin were shown to be associated with tumorigenesis (see Box 2), suggesting that progranulin functions as an autocrine growth factor [4]. Progranulin may promote cell proliferation and survival by activating proteins in multiple extracellular signaling pathways, including the MAPK extracellular signal-related kinase (Erk1/2) and the PI-3 kinase effectors Akt1 and p70-S6 kinase [4]. Progranulin may also act as an atypical growth factor. Progranulin promotes the passage of fibroblasts lacking insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) receptor through all stages of the cell cycle, as opposed to just the S-phase or the M-phase usually seen with other growth factors [4]. This finding suggests that progranulin and IGF-I signaling pathways share common downstream mechanisms. The relevance of these signaling pathways to neural and metabolic cell types is unclear. The impact of progranulin cleavage to granulins for signaling is also unclear.

BOX 2. Progranulin and cancer.

Early work demonstrated progranulin’s ability to stimulate cell division in cultured cell lines and promote anchorage independent growth [90]. For example, knockdown of progranulin expression reduced tumorigenicity of a breast cancer-derived cell line, and overexpression of progranulin conferred robust tumor formation properties onto previously weak tumor forming cells [4]. Subsequent studies identified progranulin’s role as an enhancer of key steps in tumorigenesis, including proliferation, survival, migration, invasion and angiogenesis [4]. High levels of progranulin correlate with increased tumor severity, increased risk of reoccurrence, and chemoresistance, making progranulin expression a potentially valuable prognostic indicator [90]. Indeed, progranulin neutralizing antibodies are in preclinical development for the treatment of breast and lung cancer (www.agpharma.com). Progranulin’s role in the progression of cancer must be carefully considered when evaluating potential progranulin-elevating therapeutics for the treatment of progranulin-deficient FTD (see Table 1). Ideal candidates might restore progranulin to normal levels.

The Search for Progranulin Receptors and Binding Proteins

The recent identification of progranulin receptor(s) was a much-anticipated first step towards understanding the signaling cascade(s) that mediate progranulin function. In 2010, the extreme C-terminal three amino acids of progranulin were reported as being necessary for progranulin to bind sortilin [5, 6], a multi-ligand type-I receptor that regulates intracellular protein trafficking in the Golgi and acts as a clearance receptor on the cell surface. Sortilin-deficient (Sort1−/−) mice exhibited fivefold more circulating progranulin [6], and serum progranulin levels in humans were influenced by sortilin expression [7], suggesting that sortilin is involved in progranulin’s endocytic processing and/or degradation. Indeed, in addition to its localization in the ER and Golgi of microglia, progranulin was detected in the lysosomes of astrocytes grown in mixed cultures with neurons [8]. Inasmuch as astrocytes do not express progranulin [9], this might reflect sortilin-mediated uptake of neuron-derived progranulin. Nonetheless, in the absence of sortilin, exogenous progranulin promotes neurite outgrowth [10] and enhances survival of progranulin knockout cells [11], suggesting other receptors mediate these functions of progranulin. The role of sortilin-binding may be limited to sorting and recycling or possibly to acting as a co-receptor with an unidentified partner [12]. Indeed, progranulin binds to Sort1−/− neurons [6], further suggesting the existence of additional neuronal progranulin receptors.

In 2011, progranulin was reported to bind the tumor necrosis factor receptors (TNFRs), thereby blocking receptor activation by binding of TNFα and initiation of downstream signaling cascades [13]. Although involvement of this pathway is appealing given the strong evidence that progranulin modulates inflammation, a recent study did not detect this TNFR interaction [14], thus more studies are needed to clarify if progranulin is a TNFR ligand. Nevertheless, many studies agree that progranulin has anti-inflammatory properties [15]. Progranulin robustly suppresses chronic inflammation in mouse models of arthritis [13] and may have significant implications for treating progranulin-deficient inflammatory disease, such as FTD. In addition, progranulin acts on neurons to promote neurite outgrowth, a process that is regulated by TNFRs [10]. Understanding whether these actions of progranulin occur via the TNFRs or other receptors is important.

There is little information on receptors for granulins. Granulins act as cofactors for the binding of CpG oligonucleotides, common in bacterial DNA, to toll-like receptor 9 in the endolysosome [16], an event critical for initiating the innate immune response. Since the sequence homology of granulins is mostly conserved cysteines, (see Box 1), it will be interesting to see if all granulins bind the same receptor(s) or if different receptors exist for different granulins.

Circulating progranulin interacts with soluble binding partners (see [15] for a comprehensive table), including secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) [17]. SLPI binding to progranulin blocks elastase-mediated cleavage into granulins, resulting in blunted activation of cultured neutrophils and improved wound healing in Slpi−/− mice [17]. These results are consistent with granulins’ pro-inflammatory properties and with progranulin’s ability to promote tissue repair. Recently, circulating progranulin was shown to exist as homodimers [18]. It remains to be determined how dimerization affects progranulin’s binding to SLPI, susceptibility to cleavage, or overall function.

Progranulin Deficiency Causes Frontotemporal Dementia

FTD is the most common neurodegenerative disease in individuals under the age of 60 [19]. It typically strikes in late middle age and is distinct from Alzheimer disease and psychiatric disorders, although its symptoms are often confused with the latter. Affected individuals display personality, behavior, and/or language abnormalities associated with atrophy of the frontal and temporal brain lobes [20]. Memory is typically spared. Approximately 40% of cases have family histories with dominantly inherited genetic mutations that cause FTD; of these, approximately 5–20% are caused by progranulin gene (GRN) mutations [21].

To date, 69 GRN mutations, spanning the entire gene, have been found to cause FTD (see http://www.molgen.vib-ua.be/FTDMutations) [21]. GRN mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner with high penetrance [1]. Most mutations result in a premature termination codon in one allele, causing the mutant mRNA to be targeted for nonsense-mediated decay and creating a functionally null allele [22]. Other mutations are predicted to produce a nonfunctional or unstable protein [22]. Therefore, progranulin-deficient FTD is a disease of haploinsufficiency caused by progranulin loss of function [22]. In mutation carriers, serum progranulin levels are often reduced by 70–80% compared with controls [23] rather than the 50% expected by loss of one allele, suggesting additional regulation of progranulin’s expression. In human lymphoblasts, methylation of CpG units 1–2 kb distal to progranulin’s transcription start site is inversely correlated with its expression, suggesting altered epigenetic modifications partially explains the lower-than-expected expression of progranulin in mutation carriers [24]. In agreement with this, GRN mRNA levels in fibroblasts from GRN mutation heterozygous carriers are less than 50% of control subjects. However, when reprogrammed to pluripotent stem cells, which removes most epigenetic modifications, GRN mRNA levels are restored to ~50% [25]. These latter studies suggest that epigenetic mechanisms influence progranulin levels in mutation carriers and that better understanding of these mechanisms might be useful for therapies aimed at raising their progranulin levels. Reduced progranulin levels may also be a risk factor for Alzheimer disease [26] and possibly autism [27], adding additional import to understanding epigenetic modifiers of progranulin expression.

Genetic modifiers of progranulin expression, which are possible targets for disease intervention, include several microRNAs and TMEM106b, a lysosomal transmembrane glycoprotein. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the 3′ UTR of progranulin affects a predicted binding site for miR-659 and alters gene expression [28]. Similarly, miR-29b [29] and miR-107 [30] also regulate progranulin expression. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of progranulin mutation carriers identified SNPs in or near TMEM106b that impacted the age of onset of FTD [31, 32]. Specifically, a protective SNP, which correlated with a delayed age of onset and relatively mild symptoms in the small sample size of progranulin mutation carriers with this protective allele, was identified. The function of TMEM106b is unclear, but it may be required for endolysosomal homeostasis [33], which, as is discussed below, is an emerging theme in FTD research.

Neuropathological hallmarks of progranulin-deficient FTD include dystrophic neurites, inflammation, neuronal and microglial ubiquitin-positive inclusions, and severe neuron loss in the frontal and temporal lobes. Pathologic changes are also observed in the striatum, thalamus, substantia nigra, and hippocampus [20, 34]. Intracellular inclusions do not contain progranulin, but instead contain hyperphosphorylated, ubiquitinylated, and proteolytically cleaved Tar DNA–binding protein-43 (TDP-43) [22]. TDP-43 is a highly conserved, ubiquitous DNA- and RNA-binding protein that binds many mRNAs, including GRN, and functions as a transcriptional repressor and inhibitor of exon splicing [35]. TDP-43 aggregates are also found in the motor neurons of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients, and mutations in the TDP-43 gene TARDBP cause ALS, suggesting common pathological etiologies for FTD and ALS [35]. Indeed, progranulin mutations modify the course of ALS [36] and, in rare cases, cause ALS [37], and FTD and ALS both result in the loss of large neurons: von Economo neurons in the frontal lobes in FTD [38] and motor neurons in ALS [39].

Recently, two individuals with homozygous GRN mutations were reported. These individuals had undetectable levels of circulating progranulin, progressive vision loss, retinal dystrophy, ataxia, and seizures in their third decade of life [40]. Interestingly, while loss of one functional GRN allele leads to FTD, loss of both alleles results in neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL). NCLs are a group of lysosomal storage disorders characterized by progressive degeneration of the brain and retina, with accelerated intracellular accumulation of lipofuscin [41], a lipid-containing pigment related to lysosmal degradation dysfunction and associated with aging. It remains to be seen whether progranulin-deficient NCL patients will also exhibit FTD-like pathology in their frontal and temporal lobes with age.

The link of progranulin to lysosomal disease suggests that progranulin and/or granulins may have a distinct function in the lysosomal compartment, possibly as activators of transporters of lysosomal enzymes [42]. This discovery therefore significantly altered the FTD field by implying that a key function of progranulin may reside in the lysosome. The notion that altered vesicle trafficking and protein homeostasis may be central to FTD pathogenesis is supported by the alterations observed in cells with mutations in two other genes that more rarely cause FTD [1]: charged multivesicular body 2B (CHMP2B) and valosin-containing protein (VCP). CHMP2B encodes a subunit of the ESCRTIII complex involved in endosomal trafficking and degradation, and mutations result in impaired fusion of endosomes with lysosomes [43]. VCP is an ATPase with multiple functions, including endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of misfolded proteins. VCP mutations result in vacuolization and impaired protein degradation, autophagy, and mitochondrial function [44]. The convergence of similar biological pathways underlying three genes associated with inherited FTD suggests a common mechanism, and therefore, a common therapeutic strategy may be possible.

Modeling CNS Progranulin Deficiency and FTD in Mice

Progranulin knockout (Grn−/−) mouse models [45-49] accelerated our understanding of progranulin’s function in the CNS. Each lab’s mouse line exhibited abnormalities in social behavior without gross deficiencies in overall health. In the brain, Grn−/− mice exhibit pathology reminiscent of FTD, with gliosis in the cortex, hippocampus and thalamus, and accumulation of ubiquitin-positive aggregates [47-52] Aggregates also contain lipofuscin [49] and phosphorylated TDP-43 [48, 52], although mislocalized TDP-43 has not been not found in cortical neurons. Unlike human FTD patients, Grn–/– mice do not show neuronal death and brain-mass loss [49]. However, Grn−/− mice exhibit increased susceptibility to neuroinflammation and neuron loss after 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) toxin–induced injury [45], social deficits [47, 51, 52], impaired learning and memory in older (13–18 mo) mice [51, 52] depression-like behaviors [52], and anxiety alterations [46, 47, 52], consistent with various behavioral symptoms associated with human FTD. This modeling of FTD-like behavior defects is quite remarkable, given the considerable differences between the frontal lobes of mice and humans.

Interestingly, neuroinflammation and gliosis are absent in Grn+/− mice up to 12 months of age, yet these animals still exhibit some social and emotional changes reminiscent of FTD as early as 6 months [53]. These changes may result from reduced neuronal activation in the amygdala, a region of the brain critical for fear and social behaviors [53]. Why loss of only one GRN allele results in robust neuropathological changes in humans, including neuroinflammation and neuronal death, yet only localized neuronal changes in mice, is unknown. Although the relationship of neuronal injury and neuroinflammation in FTD mouse models is unclear, these findings suggest neuronal effects of progranulin deficiency might be a primary cause of FTD, with increased inflammation as a secondary confounder.

Progranulin-Deficient Mice Also Exhibit Peripheral Phenotypes

In the periphery, Grn–/– mice display alterations in bone, adipose tissue, and the immune system. Chondrocyte-specific knockdown of Grn leads to reduced cartilage mass and decreased femur growth–plate size [54], consistent with progranulin’s function as a growth factor. As discussed in detail below, Grn−/− mice are also protected from high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance [3]. In addition, Grn−/− mice have increased susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis [13], contact dermatitis [55] and infection with Listeria monocytogenes [48], providing evidence of multiple deficiencies in the immune response.

Progranulin Is Linked to Metabolic Diseases, including Type 2 Diabetes

Progranulin and metabolic disease were linked when individuals with visceral obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) were shown to have 1.4-fold increased serum progranulin levels [56]. Additionally, circulating progranulin levels were positively correlated with body mass index (BMI), fat mass, fasting glucose and insulin levels, and insulin resistance, a hallmark of T2D [57]. Circulating progranulin levels are higher in insulin-resistant, compared with insulin-sensitive, obese individuals [58], and, most recently, increased plasma progranulin levels were reported in individuals with T2D, as well as in obese individuals [2]. Other recent studies reported that circulating progranulin levels are independent of BMI and/or insulin, but these studies included subjects with complicating conditions, such as gestational diabetes [59], renal failure [60], or post-nutritional weight loss [61]. Thus, in the absence of specific comorbid conditions, circulating progranulin levels appear to be a useful biomarker for inflammation and T2D related to obesity. Further studies are needed to determine if measuring progranulin levels will be useful as a biomarker of metabolic syndrome.

In contrast to other studies showing progranulin has anti-inflammatory actions, recent studies in mice identified progranulin as a proinflammatory adipokine that is expressed in adipocytes and macrophages in white adipose tissue [3]. Grn−/− mice consuming a high-fat diet (HFD) were protected from HFD-induced obesity, adipocyte hypertrophy, and insulin resistance [3]. Knockdown of progranulin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes abolished TNFα-induced expression of IL-6, an inflammatory adipokine involved in the development of insulin resistance, and insulin resistance induced by systemic injections of recombinant murine progranulin was blocked by administering neutralizing antibodies against IL-6 [3]. Thus, progranulin may promote insulin resistance by increasing IL-6 expression.

Progranulin might also promote insulin resistance by directly inhibiting the insulin-signaling cascade. Treating 3T3-L1 adipocytes with exogenous progranulin inhibited insulin-induced phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 and Akt in a dose-dependent manner, while knockdown of progranulin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes enhanced insulin sensitivity [3]. The phosphorylation of insulin receptor in response to insulin was not affected, suggesting that progranulin inhibits insulin signaling at an early step between insulin receptor phosphorylation and IRS-1 phosphorylation. Thus, progranulin is an important adipokine that promotes insulin resistance by increasing levels of IL-6 and inhibiting the insulin-signaling cascade [3].

However, the situation for progranulin and insulin resistance may be more complex. The studies in mice did not examine the effects of progranulin processing to granulin peptides, and so, it is unclear whether progranulin or granulins were responsible for the observed findings. For example, progranulin-cleaving proteases, such as elastase and proteinase 3, may cleave exogenously added progranulin, thereby shifting the progranulin/granulin balance toward pro-inflammatory granulins. In this case, granulins, rather than progranulin, would be pro-inflammatory under conditions of HFD-induced diabetes. Further studies are needed to unravel the relative roles of progranulin and granulins in obesity and insulin resistance.

Tissue Repair and Remodeling May Explain Progranulin’s Role in Metabolic Disease

Why are progranulin levels elevated in obesity and T2D? What are the functional consequences of this elevation? Tissue repair and remodeling through inflammation and vascularization are central to metabolic disease. Chronic inflammation is widely recognized as a key consequence of obesity and T2D [62] and is characterized by increased secretion of cytokines and chemokines and the recruitment and activation of innate immune cells, such as monocytes and neutrophils to adipose tissue. As a result, obese and T2D individuals have increased plasma levels of pro-inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), TNFα, and IL-6 [63]. In addition, TNFα treatment increases progranulin mRNA levels in cultured macrophages [64] and adipocytes [3]. Therefore, the increase in circulating progranulin in individuals with obesity and T2D is likely a consequence of increased inflammatory adipokines and cytokines.

Whether the upregulation of progranulin promotes or quells obesity-induced inflammation is under debate. In support of the notion that progranulin suppresses the inflammatory response, progranulin has been reported to suppress arthritis in animal models [13]. Consistent with this idea, progranulin-deficient macrophages exhibit an exaggerated response to pro-inflammatory stimuli [45, 48]. Indeed, with the exception of obesity-induced insulin resistance, the bulk of evidence suggests progranulin is anti-inflammatory. However, in a chronic disease setting, progranulin may promote inflammation through monocyte recruitment. Progranulin promotes monocyte chemotaxis in vitro as effectively as the potent chemotactic molecule macrophage chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, and its levels significantly correlate with macrophage infiltration of omental adipose tissue in vivo [56]. Thus, increased progranulin levels in obesity and T2D may contribute to the chronic inflammatory state by increasing macrophage recruitment to adipose tissue.

The upregulation of progranulin levels in obesity might also reflect tissue remodeling. Increased vascularization is a contributing factor to the growth and remodeling of adipose tissue in obesity [65]. Progranulin is detected in proliferating blood vessels [66], and transgenic mice overexpressing progranulin in endothelial cells exhibited vascular abnormalities in late gestation [67]. In cancers, progranulin stimulates the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [68], a major angiogenic factor, although a similar effect was not observed in the mice with endothelial overexpression [67]. Finally, progranulin stimulates migration and invasiveness in breast cancer cells [68]. Since progranulin expression in adipose tissue positively correlates with BMI in humans [56] and is increased in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity [3], elevated progranulin levels may contribute to the development of obesity by stimulating angiogenesis and promoting growth of adipose tissue. Collectively, these studies suggest the elevated circulating progranulin levels in obese and diabetic states result from the upregulation of progranulin expression in response to adipose tissue repair and remodeling.

Progranulin Regulates Energy Balance—Further Links between Metabolism and the Brain?

Mice lacking progranulin are lean and protected from obesity, suggesting that progranulin also regulates energy balance. Although a small decrease was detected in respiratory exchange rate in Grn−/− mice during the dark cycle, overall, neither their food intake nor energy expenditure appears to differ from wild-type mice [3]. However, assessing energy balance in mice is challenging [69], and changes in energy expenditure might have been missed.

The hypothalamus coordinates glucose sensing and appetite control, and several hypothalamic cell types express progranulin, including neurons, microglia, and epithelial-like cells called tanycytes (specialized ependymal cells believed to transfer chemical signals from the CNS to the bloodstream). Administration of purified progranulin into the intraventricular space in mice suppressed nocturnal feeding, while injection of progranulin siRNA into the hypothalamus increased food intake and promoted weight gain [70]. Interestingly, dysregulated feeding behavior, such as overeating and a preference for sweets, together with concomitant hypothalamic atrophy, is commonly noted in FTD patients [71]. Mechanistically, progranulin upregulated the anorexigenic factor proopiomelanocortin and downregulated the orexigenic factors neuropeptide Y and Agouti-related peptide; based on these data, Kim et al. concluded that progranulin in the hypothalamus acted as an anorexigenic factor that decreased appetite in the fed state. However, the progranulin concentrations that elicited effects are 3,000–10,000 times higher than those reported in human CSF. Further, since food intake was not altered in Grn−/− mice fed a regular or high-fat diet [3], it remains unclear whether progranulin plays a role in the physiological control of food intake. Adding to the uncertainty, human studies of progranulin and energy balance are limited, but surprisingly, circulating progranulin levels may positively predict resting metabolic rate when normalized for body weight [57].

Progranulin May Modulate Processes Involved in Atherosclerosis

Recent studies indicate a functional link of progranulin with atherosclerosis, another metabolic disease involving the inflammatory process. Atherosclerosis results from the accumulation of cholesterol in macrophages of the arterial wall that leads to formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Critical to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis are inflammation and proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) toward the intima, the innermost arterial layer. Progranulin modulates both of these processes. Indeed, progranulin has been detected in human atherosclerotic plaques by immunohistochemistry, specifically in the VSMC of the intima and in macrophages [72]. Moreover, progranulin modulates migration of human aortic smooth muscle cells in culture, suggesting its trophic properties may influence atherosclerotic plaque formation [72]. Full-length progranulin is expected to be anti-atherogenic whereas granulins might be pro-atherogenic, owing to their purported respective anti- and pro-inflammatory properties. Indeed, recently progranulin deficiency was shown to exacerbate atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein (apo-) E knockout mice fed a high fat diet, with increased inflammatory cytokine production and enhanced cholesterol accumulation in macrophages [73]. Interestingly, in humans, elevated serum progranulin levels were reported to be an independent positive predictor of atherosclerosis, based on measurements of carotid intima-media thickness [74].

Progranulin might also affect plasma lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis through sortilin [6]. Sortilin reduces circulating LDL levels by both increasing sortilin-mediated uptake and catabolism of LDL [75, 76] and decreasing secretion of apoB-containing very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) [76, 77]. It remains to be determined whether progranulin binding to sortilin has functional consequences for LDL metabolism.

High plasma levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL) are inversely correlated with atherosclerosis, and progranulin is a component of human HDL as shown by binding the major HDL protein apo-A-I [64]. Moreover, in cultured macrophages, HDL blocked cleavage of progranulin into granulins and inhibited granulin-mediated inflammation. These findings sparked considerable interest since HDL’s beneficial effects are believed to be, in part, due to its anti-inflammatory properties [78]. However, subsequent studies using several methods of HDL isolation [18] and two proteomic studies [79, 80] did not detect progranulin in human or mouse HDL. Thus, a direct link of progranulin to HDL seems unlikely.

Progranulin and Therapeutics

There is considerable interest in therapeutic approaches focused on increasing progranulin levels in FTD linked to progranulin haploinsufficiency [81, 82]. Additionally, if progranulin suppresses neuroinflammation, therapies that increase levels of progranulin in the CNS might be useful for several neurodegenerative diseases. Table 1 lists compounds and approaches that increase progranulin levels in vitro or, based on experimental evidence, are likely to do so.

TABLE 1. Compounds or approaches with potential therapeutic utility by increasing progranulin levels or actions.

Selected references are provided where applicable. These strategies are mostly directed toward FTD and neuroinflammation. Therapeutic strategies to lower progranulin are not available.

| Drug or Approach |

Known or proposed activity and use | Known or (proposed) effect on target |

Cell and/or tissue type; organism |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| microRNA knockdown (miR-29b) |

miR-29b is one of a cluster of 4 closely miRs which regulate diverse cellular processes. Reduction of miR-29b increased GRN mRNA in cultured cells |

Increased progranulin protein |

HEK293 and 3T3 cells; human |

[29] |

| Progranulin C- terminal peptide |

Progranulin’s C-terminal 3 residues are required to bind sortilin. Circulating progranulin levels increase in sortilin-deficient mice. Exogenous peptide containing progranulin’s C-terminus could compete for sortilin binding. |

Increased circulating progranulin (proposed) |

Neurons; human (proposed) |

[5, 6] |

| Protein disulfide isomerase 4 (PDI4) overexpression |

PDI4 is an ER-chaperone required for disulfide- mediated protein folding. Overexpression increases secreted progranulin in cultured cells |

Increased progranulin protein |

HEK293 cells; human | [8] |

| Recombinant progranulin (by pump) |

Direct replacement of purified progranulin protein |

Increased progranulin protein (proposed) |

Nervous system; human (proposed) |

n/a |

| Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) or other HDAC inhibitors |

SAHA is a histone deacetylase used to treat cancer. It upregulated progranulin expression in GRN+/− patient cells to nearly wild-type levels. |

ncreased GRN mRNA |

N2A cells and primary dermal fibroblasts from progranulin mutation carriers; human and mouse |

[82] |

| Upregulation of vacuolar ATPase |

Selective inhibitor of vacuolar ATPase in cultured cells increased progranulin via a translational mechanism independent of lysosomal degradation, autophagy, or endocytosis |

Increased progranulin secretion |

HeLa and HEK293T cells and MEFs; human and mouse |

[81] |

| Viral gene replacement therapy (GRN expression) |

Increased expression of progranulin by introduction of exogenous transgene |

Increased GRN mRNA |

Primary neuronal and microglial cultures; mouse |

n/a |

| WNT antagonists |

The WNT signaling pathway is upregulated in progranulin-deficient human cells, mice and worms. |

Block upregulation of WNT signaling pathway (proposed) |

Nervous system; human (proposed) |

[93] |

In theory, restoring progranulin levels in the brain by increasing expression from the remaining functional allele or promoting progranulin secretion should provide therapeutic benefit for progranulin-deficient FTD and possibly other neurodegenerative diseases characterized by impaired tissue remodeling or inflammation. However, therapies aimed at increasing progranulin levels should be approached cautiously as, in addition to promoting insulin resistance in obesity [3], progranulin can promote tumor growth [4] (see Box 2). Furthermore, our understanding of the relationship between anti-inflammatory progranulin and its processing to the pro-inflammatory granulins remains limited. If FTD and associated neuroinflammation exacerbates the cleavage of progranulin into granulins, and granulins promote disease via their pro-inflammatory properties, then increasing progranulin levels could paradoxically be counter-therapeutic. A better understanding of the relationship between progranulin and granulin biology, and between progranulin and angiogenesis, remains an important challenge.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Progranulin’s importance in neurodegeneration is well established, but the links of progranulin to diseases of metabolism and inflammation are more recent, and information is limited. Paradoxically, progranulin suppresses neuroinflammation and neuronal death in the CNS and appears to suppress atherosclerosis, but is apparently a pro-inflammatory molecule in the context of diet-induced obesity (see Box 3). Resolving this paradox will require a better understanding of progranulin’s tissue- and cell-specific actions, its proteolytic processing, and its receptor(s) and signaling pathways. In particular, further unraveling of progranulin and granulin peptides effects on growth and inflammation and as modulators of tissue repair in response to injury may provide a useful framework for unraveling the complex biology of progranulin. Such insights into the basic biology of progranulin will undoubtedly help to guide therapeutic strategies.

BOX 3. Outstanding questions.

What are the molecular regulators of progranulin and granulins? What are their respective receptors and signaling pathways and how do they interact?

What are the relative functions of progranulin versus granulin peptides? Do different granulins have similar or opposing activities?

Is the cleavage of progranulin into granulins altered in disease states?

Is progranulin’s primary FTD-relevant function in neurons or microglia? Similarly, is progranulin’s primary metabolic disease-relevant function in adipocytes, monocytes, endothelial cells, or vascular smooth muscle cells?

How does progranulin regulate energy balance in the CNS?

Which of progranulin’s functions (e.g., trophic factor, anti-inflammatory molecule, granulin precursor, growth factor) are key to the development of neurodegenerative disease or metabolic disease?

Highlights.

Progranulin is a secreted glycoprotein found in plasma and CSF

Progranulin has growth factor–like and inflammation-related properties

Progranulin deficiency causes a neurodegenerative disease – frontotemporal dementia

Obese and type 2 diabetic individuals have increased serum progranulin levels

Grn−/− mice are protected from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance

Figure I. (for Box 1). Overview of progranulin biochemistry.

Progranulin is composed of 7.5 highly homologous, cysteine-rich repeats called granulins, shown in blue, that are separated by linker regions, shown in white, which share less sequence homology. A signal sequence, shown in red, is required for secretion. Progranulin can be cleaved into granulins by proteases, including neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, MMP-12, ADAMTS-7, and possibly others. Cleavage can be prevented by binding to the protease inhibitor secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI). Progranulin’s reported cell-surface receptors include sortilin and TNF receptors. The binding of progranulin to TNFRs is controversial (see text). Granulin receptors are unknown.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Anna Lisa Lucido and Gary Howard for editorial assistance and Giovanni Maki for assistance with graphics. Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants P50 AG023501 to R.V. Farese, Jr., F32 HL116197 to A.D. Nguyen, and F31 AG034793 to L. H. Martens), the Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research, the American Diabetes Association, and the Gladstone Institutes. The Gladstone Institutes received support from a National Center for Research Resources grant RR18928.

GLOSSARY

- Adipokine

A signaling molecule secreted by adipose tissue that acts on the immune system.

- Atherosclerosis

A progressive disease, with a strong inflammatory component, in which an artery wall thickens as a result of the accumulation of lipids and cell proliferation.

- Body mass index (BMI)

An individual’s body mass divided by the square of their height. Obesity is often defined as BMI ≥ 30. In general, obese BMI values are associated with an increased risk of disease.

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

A serum protein synthesized and secreted by the liver in response to inflammatory molecules released by macrophages and adipocytes. It functions during the acute phase response to activate the complement system.

- Energy balance

The biological homeostasis of energy in living systems measured by the equation Energy intake = Internal heat produced + External work + Energy stored.

- Frontotemporal dementia (FTD)

A group of complex neurodegenerative diseases characterized by progressive deterioration of the frontotemporal lobes resulting in behavioral and/or speech changes. FTD generally begins in the mid-50s and is more common than Alzheimer disease in this age group, with a prevalence of 3–15 cases per 100,000. Patients with pathogenic mutations in one copy of progranulin develop FTD.

- Gliosis

The proliferation of glial cells (microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes) in response to brain insults. Gliosis is believed to have both beneficial and destructive consequences. FTD patients exhibit pronounced gliosis.

- Hypothalamus

A region in the ventral part of the brain, above the brain stem, that coordinates with the endocrine system to regulate and/or respond to hunger, thirst, body temperature, sleep, circadian cycles, and fatigue.

- Microglia

Resident immune cells of the brain, analogous in function to their peripheral counterparts, macrophages. Microglia, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes are the main glial cell types in the brain.

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL)

A group of neurodegenerative disorders characterized by the accumulation of oxidized lipids and proteins in the brain, liver, spleen, and kidneys. Patients with pathogenic mutations in two copies of progranulin develop NCL.

- Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI)

An inhibitor of elastase, a protease that cleaves progranulin into granulins. When progranulin is complexed with SLPI, proteolytic processing by elastase is prevented.

- Sortilin

A transmembrane sorting receptor mainly expressed in the nervous system that mediates trafficking of numerous unrelated neuropeptides, including progranulin, to endosomes and lysosomes.

- Type 2 diabetes (T2D)

Also known as adult-onset diabetes; a common metabolic disorder characterized by high blood glucose levels in the context of insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rademakers R, et al. Advances in understanding the molecular basis of frontotemporal dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:423–434. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qu H, et al. Plasma progranulin concentrations are increased in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity and correlated with insulin resistance. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:360190. doi: 10.1155/2013/360190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsubara T, et al. Pgrn is a key adipokine mediating high fat diet-induced insulin resistance and obesity through il-6 in adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2012;15:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman A, Bennett HPJ. The granulin gene family: From cancer to dementia. Bioessays. 2009;31:1245–1254. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Y, et al. C-terminus of progranulin interacts with the beta-propeller region of sortilin to regulate progranulin trafficking. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu F, et al. Sortilin-mediated endocytosis determines levels of the frontotemporal dementia protein, progranulin. Neuron. 2010;68:654–667. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrasquillo MM, et al. Genome-wide screen identifies rs646776 near sortilin as a regulator of progranulin levels in human plasma. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:890–897. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almeida S, et al. Progranulin, a glycoprotein deficient in frontotemporal dementia, is a novel substrate of several protein disulfide isomerase family proteins. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan C, et al. Progranulin is expressed within motor neurons and promotes neuronal cell survival. BMC neuroscience. 2009;10:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gass J, et al. Progranulin regulates neuronal outgrowth independent of sortilin. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Muynck L, et al. The neurotrophic properties of progranulin depend on the granulin e domain but do not require sortilin binding. Neurobiol Aging. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nykjaer A, Willnow TE. Sortilin: A receptor to regulate neuronal viability and function. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang W, et al. The growth factor progranulin binds to tnf receptors and is therapeutic against inflammatory arthritis in mice. Science. 2011;332:478–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1199214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, et al. Progranulin does not bind tumor necrosis factor (tnf) receptors and is not a direct regulator of tnf-dependent signaling or bioactivity in immune or neuronal cells. J Neurosci. 2013;33:9202–9213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5336-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jian J, et al. Insights into the role of progranulin in immunity, infection, and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93:199–208. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0812429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park B, et al. Granulin is a soluble cofactor for toll-like receptor 9 signaling. Immunity. 2011;34:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu J, et al. Conversion of proepithelin to epithelins: Roles of slpi and elastase in host defense and wound repair. Cell. 2002;111:867–878. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen AD, et al. Secreted progranulin is a homodimer and is not a component of high density lipoproteins (hdl) J Biol Chem. 2013;288:8627–8635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knopman DS, Roberts RO. Estimating the number of persons with frontotemporal lobar degeneration in the us population. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2011;45:330–335. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9538-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. Loss of progranulin function in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Trends Genet. 2008;24:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruts M, et al. Locus-specific mutation databases for neurodegenerative brain diseases. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:1340–1344. doi: 10.1002/humu.22117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rademakers R, Rovelet-Lecrux A. Recent insights into the molecular genetics of dementia. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finch N, et al. Plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutation status in frontotemporal dementia patients and asymptomatic family members. Brain. 2009;132:583–591. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banzhaf-Strathmann J, et al. Promoter DNA methylation regulates progranulin expression and is altered in ftld. Acta Neuropathologica Comm. 2013;1 doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almeida S, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell models of progranulin-deficient frontotemporal dementia uncover specific reversible neuronal defects. Cell Rep. 2012;2:789–798. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perry DC, et al. Progranulin mutations as risk factors for alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:774–778. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Ayadhi LY, Mostafa GA. Low plasma progranulin levels in children with autism. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2011;8:111. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rademakers R, et al. Common variation in the mir-659 binding-site of grn is a major risk factor for tdp43-positive frontotemporal dementia. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17:3631–3642. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiao J, et al. Microrna-29b regulates the expression level of human progranulin, a secreted glycoprotein implicated in frontotemporal dementia. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W-X, et al. Mir-107 regulates granulin/progranulin with implications for traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative disease. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:334–345. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Deerlin VM, et al. Common variants at 7p21 are associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tdp-43 inclusions. Nat Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ng.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finch N, et al. Tmem106b regulates progranulin levels and the penetrance of ftld in grn mutation carriers. Neurology. 2010 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820a0e3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholson AM, et al. Tmem106b p.T185s regulates tmem106b protein levels: Implications for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurochem. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jnc.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eriksen JL, Mackenzie IRA. Progranulin: Normal function and role in neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2008;104:287–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sephton CF, et al. Tdp-43 in central nervous system development and function: Clues to tdp-43-associated neurodegeneration. Biol Chem. 2012;393:589–594. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sleegers K, et al. Progranulin genetic variability contributes to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;71:253–259. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000289191.54852.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schymick JC, et al. Progranulin mutations and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal dementia phenotypes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2007;78:754–756. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.109553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allman JM, et al. The von economo neurons in the frontoinsular and anterior cingulate cortex. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1225:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Chalabi A, et al. The genetics and neuropathology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:339–352. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith KR, et al. Strikingly different clinicopathological phenotypes determined by progranulin-mutation dosage. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:1102–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kohlschütter A, Schulz A. Towards understanding the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Brain Dev. 2009;31:499–502. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cenik B, et al. Progranulin: A proteolytically processed protein at the crossroads of inflammation and neurodegeneration. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:32298–32306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.399170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urwin H, et al. The role of chmp2b in frontotemporal dementia. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;37:208. doi: 10.1042/BST0370208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamanaka K, et al. Recent advances in p97/vcp/cdc48 cellular functions. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1823:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martens LH, et al. Progranulin deficiency promotes neuroinflammation and neuron loss following toxin-induced injury. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3955–3959. doi: 10.1172/JCI63113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kayasuga Y, et al. Alteration of behavioural phenotype in mice by targeted disruption of the progranulin gene. Behav Brain Res. 2007;185:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petkau TL, et al. Synaptic dysfunction in progranulin-deficient mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin F, et al. Exaggerated inflammation, impaired host defense, and neuropathology in progranulin-deficient mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:117–128. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmed Z, et al. Accelerated lipofuscinosis and ubiquitination in granulin knockout mice suggest a role for progranulin in successful aging. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:311–324. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wils H, et al. Cellular ageing, increased mortality and ftld-tdp-associated neuropathology in progranulin knockout mice. J. Pathol. 2012;228:67–76. doi: 10.1002/path.4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghoshal N, et al. Core features of frontotemporal dementia recapitulated in progranulin knockout mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:395–408. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yin F, et al. Behavioral deficits and progressive neuropathology in progranulin-deficient mice: A mouse model of frontotemporal dementia. FASEB J. 2010;24:4639–4647. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-161471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Filiano AJ, et al. Dissociation of frontotemporal dementia-related deficits and neuroinflammation in progranulin haploinsufficient mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5352–5361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6103-11.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng JQ, et al. Granulin epithelin precursor: A bone morphogenic protein 2-inducible growth factor that activates erk1/2 signaling and junb transcription factor in chondrogenesis. FASEB J. 2010;24:1879–1892. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Y-P, et al. Progranulin deficiency exaggerates, whereas progranulin-derived atsttrin attenuates, severity of dermatitis in mice. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1805–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Youn B-S, et al. Serum progranulin concentrations may be associated with macrophage infiltration into omental adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2009;58:627–636. doi: 10.2337/db08-1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hossein-Nezhad A, et al. Obesity, inflammation and resting energy expenditure: Possible mechanism of progranulin in this pathway. Minerva Endocrinol. 2012;37:255–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klöting N, et al. Insulin-sensitive obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E506–515. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00586.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Todoric J, et al. Circulating progranulin levels in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and healthy controls during and after pregnancy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167:561–567. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richter J, et al. Serum levels of the adipokine progranulin depend on renal function. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:410–414. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blüher M, et al. Two patterns of adipokine and other biomarker dynamics in a long-term weight loss intervention. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:342–349. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Romeo GR, et al. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and roles of inflammation--mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1771–1776. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taube A, et al. Inflammation and metabolic dysfunction: Links to cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2148–2165. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00907.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okura H, et al. Hdl/apolipoprotein a-i binds to macrophage-derived progranulin and suppresses its conversion into proinflammatory granulins. Journal of atherosclerosis and thrombosis. 2010;17:568–577. doi: 10.5551/jat.3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cao Y. Angiogenesis modulates adipogenesis and obesity. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2362–2368. doi: 10.1172/JCI32239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gonzalez EM, et al. A novel interaction between perlecan protein core and progranulin: Potential effects on tumor growth. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38113–38116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toh H, et al. Expression of the growth factor progranulin in endothelial cells influences growth and development of blood vessels: A novel mouse model. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tangkeangsirisin W, Serrero G. Pc cell-derived growth factor (pcdgf/gp88, progranulin) stimulates migration, invasiveness and vegf expression in breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1587–1592. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tschöp MH, et al. A guide to analysis of mouse energy metabolism. Nat Methods. 2012;9:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim H-K, et al. Involvement of progranulin in hypothalamic glucose sensing and feeding regulation. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4672–4682. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piguet O, et al. Eating and hypothalamus changes in behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:312–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.22244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kojima Y, et al. Progranulin expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaque. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kawase R, et al. Deletion of progranulin exacerbates atherosclerosis in apoe knockout mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoo HJ, et al. Implication of progranulin and c1q/tnf-related protein-3 (ctrp3) on inflammation and atherosclerosis in subjects with or without metabolic syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Linsel-Nitschke P, et al. Genetic variation at chromosome 1p13.3 affects sortilin mrna expression, cellular ldl-uptake and serum ldl levels which translates to the risk of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Strong A, et al. Hepatic sortilin regulates both apolipoprotein b secretion and ldl catabolism. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2807–2816. doi: 10.1172/JCI63563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Musunuru K, et al. From noncoding variant to phenotype via sort1 at the 1p13 cholesterol locus. Nature. 2010;466:714–719. doi: 10.1038/nature09266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haas MJ, Mooradian AD. Inflammation, high-density lipoprotein and cardiovascular dysfunction. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:265–272. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328344b724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gordon SM, et al. Proteomic characterization of human plasma high density lipoprotein fractionated by gel filtration chromatography. Journal of proteome research. 2010;9:5239–5249. doi: 10.1021/pr100520x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vaisar T, et al. Shotgun proteomics implicates protease inhibition and complement activation in the antiinflammatory properties of hdl. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:746–756. doi: 10.1172/JCI26206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Capell A, et al. Rescue of progranulin deficiency associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration by alkalizing reagents and inhibition of vacuolar atpase. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:1885–1894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5757-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cenik B, et al. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (vorinostat) up-regulates progranulin transcription: Rational therapeutic approach to frontotemporal dementia. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16101–16108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.193433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Toh H, et al. Structure, function, and mechanism of progranulin; the brain and beyond. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2011;45:538–548. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9569-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Riz M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid progranulin levels in patients with different multiple sclerosis subtypes. Neurosci Lett. 2010;469:234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Van Damme P, et al. Progranulin functions as a neurotrophic factor to regulate neurite outgrowth and enhance neuronal survival. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:37–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Philips T, et al. Microglial upregulation of progranulin as a marker of motor neuron degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:1191–1200. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181fc9aea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen-Plotkin AS, et al. Variations in the progranulin gene affect global gene expression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17:1349–1362. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pereson S, et al. Progranulin expression correlates with dense-core amyloid plaque burden in alzheimer disease mouse models. J. Pathol. 2009;219:173–181. doi: 10.1002/path.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tanaka A, et al. Serum progranulin levels are elevated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, reflecting disease activity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R244. doi: 10.1186/ar4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.De Muynck L, Van Damme P. Cellular effects of progranulin in health and disease. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2011;45:549–560. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gass J, et al. Progranulin: An emerging target for ftld therapies. Brain Res. 2012;109:21510–21515. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wildes D, Wells JA. Sampling the n-terminal proteome of human blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4561–4566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914495107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rosen EY, et al. Functional genomic analyses identify pathways dysregulated by progranulin deficiency, implicating wnt signaling. Neuron. 2011;71:1030–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]