Abstract

Immunologically-silent phagocytosis of apoptotic cells is critical to maintaining tissue homeostasis and innate immune balance. Aged phagocytes reduce their functional activity, leading to accumulation of unphagocytosed debris, chronic sterile inflammation and exacerbation of tissue aging and damage. Macrophage dysfunction plays an important role in immunosenescence. Microglial dysfunction has been linked to age-dependent neurodegenerations. Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell dysfunction has been implicated in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Despite several reports on the characterization of aged phagocytes, the role of phagocyte dysfunction in tissue aging and degeneration is yet to be fully appreciated. Lack of knowledge of molecular mechanisms by which aging reduces phagocyte function has hindered our capability to exploit the therapeutic potentials of phagocytosis for prevention or delay of tissue degeneration. This review summarizes our current knowledge of phagocyte dysfunction in aged tissues and discusses possible links to age-related diseases. We highlight the challenges to decipher the molecular mechanisms, present new research approaches and envisage future strategies to prevent phagocyte dysfunction, tissue aging and degeneration.

Keywords: Phagocytosis, aging, phagocyte dysfunction, macrophage, microglia, retinal pigment epithelium

1. Introduction

The steady increase in life expectancy and aged population has presented us with a new challenge: age-related diseases. Tissue aging is a complex process with intertwined molecular mechanisms. Accumulation of genetic mutations, epigenetic regulation and shortening of telomeres play important roles in tissue aging (Luo et al., 2010; von Bernhardi et al., 2010). Slow buildup of deleterious products, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidized proteins, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs), generated by organism itself is the consequence of metabolism (Baquer et al., 2009; Grillo and Colombatto, 2008). Exposure to UV light and chemicals can cause tissue damage. Pathogen infection and immune response can induce bystander damage on tissues (Fricker et al., 2012). Normal aging is characterized by slow accumulation of metabolic products and mild chronic inflammation. In most cases, the chronic inflammation in aged tissues has no detectable microorganism and therefore is termed “sterile inflammation” (Chen and Nunez, 2010). Recently, the term “inflammaging” (inflammation + aging) was coined by Franceshci and colleagues to describe a common phenomenon that tissue aging is accompanied by low-grade chronic sterile inflammation (Franceschi et al., 2007). Abnormal tissue aging with excessive buildup of metabolic products and increased chronic inflammation may cause age-related diseases, thereby exacerbating tissue damage and degeneration. For example, Alzheimer’s disease is an age-related neurodegeneration characterized by amyloid plaques with activated microglia for pro-inflammatory response (Meda et al., 1995). Formation of drusen deposits in the retina is the hallmark of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which is now widely regarded as an intraocular inflammatory disease (Ding et al., 2009).

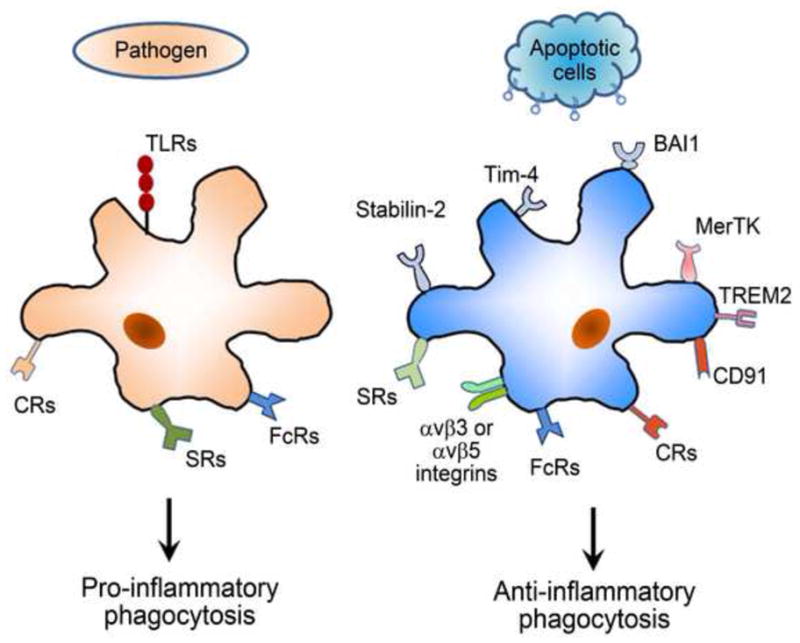

Phagocytosis is crucial to maintaining tissue homeostasis and innate immune balance, and can ingest both foreign pathogens and autologous apoptotic cells (Erwig and Henson, 2007; Napoli and Neumann, 2009). Despite the similarities in the physical process for cargo internalization, these two phagocytic events have distinct outcomes for innate and adaptive immune response (Fig. 1). Phagocytosis of infectious pathogens elicits the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Presentation of foreign antigens by professional phagocytes further induces adaptive immune response, including activation of antigen-specific lymphocytes. In contrast, phagocytosis of apoptotic cells or cellular debris triggers immunosuppressive signaling with the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines, leading to peripheral immune tolerance. Although aging affects both phagocytic events, this review mainly focuses on phagocytosis of autologous apoptotic cells or debris for in-depth understanding of how phagocyte dysfunction may exacerbate tissue aging, chronic sterile inflammation and degeneration. We also discuss newly-developed tools for elucidation of age-related molecular mechanisms and predict future research directions of the field.

Fig. 1.

Phagocytosis through different phagocytic receptors has distinct outcomes of innate immune response. Phagocytosis of infectious pathogens by macrophage and microglia through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), Fc receptors (FcRs), complement receptors (CRs) and scavenger receptors (SRs) induces pro-inflammatory response. In contrast, phagocytosis of autologous apoptotic cells or cellular debris via phosphatidylserine (PS) receptors (e.g., BAI1, stabilin-2 and Tim-4), MerTK, αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrins, TREM2, FcRs, CRs and SRs elicits anti-inflammatory response.

2. Different phagocytic receptors for pro- and anti-inflammatory response

Phagocytosis of foreign pathogens or autologous apoptotic cells is mediated by different sets of phagocytic receptors to induce pro- or anti-inflammatory response (Erwig and Henson, 2007). Infectious pathogens are phagocytosed through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), Fc receptors (FcRs), complement receptors (CRs) and scavenger receptors (SRs) to elicit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Napoli and Neumann, 2009). By contrast, apoptotic cells or cellular debris is internalized through a set of different receptors, such as phosphatidylserine receptors (e.g., BAI1, stabilin-2 and Tim-4), MerTK, αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins, TREM2, FcRs, CRs and SRs, to trigger immunosuppressive signaling with the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines (Li, 2012a).

Different receptors in the families of FcRs, CRs and SRs are capable of promoting pro- or anti-inflammatory phagocytosis with distinct intracellular signaling cascades. For example, human FcR family consists of FcγRIA, FcγRIIB (CD32B), FcγRIIA (CD32A), FcγRIIC, FcγRIIIA (CD16), and FcγRIIIB. Except FcγRIIB as an inhibitory receptor, all other FcRs induce pro-inflammatory signaling and immune activation (Ivan and Colovai, 2006). Antibody-opsonized cargos, including pathogens with neutralizing antibodies and apoptotic cells or tissue debris with autoantibodies in autoimmune diseases, can be phagocytosed via different FcRs with distinct innate immune responses. A dichotomy is that microglial phagocytosis of neuronal antigens in the initiation and recovery phase of multiple sclerosis (MS) triggers both pro- and anti-inflammatory response, respectively (Huizinga et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2007). Whether microglia phagocytose myelin debris through different FcRs at different stages of MS or whether aging may affect the expression profile of FcRs on microglia remain to be determined.

Ligand diversity further increases the complexity of the molecular regulations of phagocytosis. For example, MerTK has at least five known ligands, including Gas6, protein S, tubby, Tulp1 and galectin-3 (Gal-3) (Caberoy et al., 2012a; Caberoy et al., 2010b; Stitt et al., 1995). All these five ligands are bridging molecules with two binding domains: phagocytic receptor-binding domain (PRBD; i.e., MerTK-binding domain) and phagocytosis prey-binding domain (PPBD). Different preys or cargos will be selected for phagocytosis by their interaction with the PPBD of different MerTK ligands. One of the examples is that Gal-3 is a well-known binding protein for AGEs (Vlassara et al., 1995) and therefore may facilitate AGE clearance through the MerTK pathway.

Ligand-receptor cross-reactivity may also regulate the outcomes of the innate immune response. Phosphatidylserine is a well-characterized ligand or “eat-me” signal that facilitates phagocytosis of apoptotic cells through several immunosuppressive receptors, including BAI1, stabilin-2 and Tim-4 (Miyanishi et al., 2007; Park et al., 2007; Park et al., 2008). A recent study showed that RAGE is also a phosphatidylserine receptor for clearance of apoptotic cells (He et al., 2011). Activation of RAGE induces NF-κB activation and inflammation (Schmidt et al., 1995; Schmidt et al., 2001). It is still unclear whether phosphatidylserine-RAGE interaction may stimulate pro-inflammatory phagocytosis and promote chronic inflammation in tissue aging.

Under some circumstances, the protective role of phagocytosis via anti-inflammatory phagocytic receptors may unintentionally result in tissue damage. For instance, neuroinflammation may transiently increase the exposure of phosphatidylserine on neurons, leading to microglial phagocytic clearance of viable but stressed neurons (Fricker et al., 2012). Deletion or blockade of MFG-E8, which is a bridging molecule linking phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells to αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin on phagocytes, preserves live neurons.

3. Phagocyte dysfunction and tissue damage

Defects in phagocytosis are known to cause tissue damage. For instance, mutations of MerTK cause defects of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) phagocytosis, leading to accumulation of unphagocytosed debris in the subretinal space, photoreceptor degeneration and blindness (D’Cruz et al., 2000; Dowling and Sidman, 1962). MerTK deletion in mice also results in a defect of macrophage phagocytosis with unphagocytosed debris and increased production of autoantibodies (Scott et al., 2001). There are several mechanisms by which phagocyte dysfunction may exacerbate tissue aging and degeneration (Fig. 2). First, accumulation of unphagocytosed debris can disrupt tissue homeostasis by directly exerting cytotoxicity on cells. One of the well-known examples is the direct neurotoxicity of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease.

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of tissue degeneration accelerated by phagocyte dysfunction. Phagocyte aging and dysfunction can disrupt tissue homeostasis and innate immune balance through different mechanisms, thereby exacerbating tissue damage and degeneration.

Second, phagocytosis of aged cells or cellular debris is necessary for tissue regeneration by recycling nutrients. For example, approximately 2.4 million of aged erythrocytes are phagocytosed per second by Kupffer cells, which are macrophages in the liver, with new erythrocytes produced at the same rate (Li, 2012a). Without recycling, iron deficiency would occur due to the rapid synthesis of new hemoglobin. Given that at least 300 billion cells undergo apoptosis every day in our body (Li, 2012a), nutrient recycling via phagocytosis is crucial for tissue renewal.

Third, phagocytosis can promote cell survival, including phagocyte survival, through several mechanisms as discussed in Section 5.1.

Fourth, accumulated debris may induce chronic sterile inflammation, leading to tissue damage. One of the examples is that accumulation of AGEs, which are present in amyloid plaques in aged brain and drusen deposits in aged eye (Grillo and Colombatto, 2008; Ishibashi et al., 1998), may stimulate the receptor for AGEs (RAGE) to induce inflammation (Sims et al., 2010). Intracellular contents, such as damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs), released from dying cells are capable of inducing sterile inflammation through RAGE and other pattern recognition receptors (Sims et al., 2010).

Finally, aged phagocytes may alter the activity profile of their phagocytosis signaling pathways, thereby tipping the delicate balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory response via different sets of receptors on phagocytes. Reduced phagocytosis of apoptotic cells may result in diminished release of anti-inflammatory cytokines with increased susceptibility to chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases. For instance, deletion of MerTK receptor with immunosuppressive signaling can lead to autoimmunity (Lemke and Rothlin, 2008; Scott et al., 2001).

These mechanisms of tissue damage are further discussed for phagocytes in different organs below.

4. Phagocyte dysfunction and immunosenescence

Immunosenescence is responsible not only for diminished immune response against pathogens (Aw et al., 2007) but for the paradoxical increase in the incidence of autoimmune diseases (Goronzy and Weyand, 2012), such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis and monoclonal gammopathies (Aprahamian et al., 2008). Immunosenescence is composed of innate and adaptive immune senescence (Aw et al., 2007).

Phagocytosis is an integral part of the innate immune system. Phagocyte functional senescence has been investigated for the clearance of both foreign pathogens and autologous apoptotic cells. A number of studies showed that neutrophils from aged subjects had reduced capacity to phagocytose bacteria (Butcher et al., 2001; Simell et al., 2011; Wenisch et al., 2000). Aged monocytes or macrophages showed impaired capabilities to phagocytose both pathogenic bacteria and charcoal particles (Hearps et al., 2012; Plowden et al., 2004). Aged macrophages also exhibited other functional changes, including compromised chemotaxis, reduced expression of MHC class II molecules and decreased capacity for antigen presentation (Aw et al., 2007; Goronzy and Weyand, 2012; Solana et al., 2012). These contribute to the diminished immune response against pathogens.

In contrast to pathogen infection that occurs only occasionally throughout our lives, apoptosis is a routine biological process in nearly every organ. Prompt phagocytosis of dying cells is necessary to prevent the release of intracellular antigens or DAMPs (Sims et al., 2010), which in turn can elicit autoimmune response or sterile inflammation. One example of this is the deletion of MerTK phagocytic receptor that caused macrophage phagocytosis defect, accumulation of unphagocytosed debris and autoimmune response (Scott et al., 2001).

Compared to phagocytosis of pathogens, fewer studies have been performed to characterize phagocyte functional senescence for the clearance of apoptotic cells. Aging reduces phagocytosis of apoptotic cells both in vitro and in vivo. Peritoneal macrophages in aged mice exhibited reduced phagocytic clearance of apoptotic Jurkat cells (Aprahamian et al., 2008). Aged mice were impaired in their ability to clear apoptotic keratinocytes following UV irradiation of the skin. In vitro analysis showed that the pretreatment of macrophages with the serum from aged mice led to a reduction in their ability to phagocytose apoptotic cells compared with macrophages treated with serum from young mice (Aprahamian et al., 2008). Dendritic cells from elderly subjects showed a reduced capacity to phagocytose apoptotic cells or Dextran in vitro than dendritic cells from young subjects (Agrawal et al., 2007).

Mild chronic inflammation is a common characteristic of tissue aging. Phagocyte senescence may contribute to this sterile inflammation and tissue damage through two mechanisms of the innate immune response (Fig. 2). First, inefficient phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells may result in the release of the intracellular contents and accumulation of debris to trigger inflammation or autoimmunity (Sims et al., 2010). Second, aged phagocytes may have diminished signaling through immunosuppressive pathways, such as phosphatidylserine receptors and MerTK (Freeman et al., 2010; Lemke and Rothlin, 2008; Scott et al., 2001), thereby increasing phagocyte susceptibility to pro-inflammatory activation induced by the released intracellular contents.

5. Microglial aging and neurodegeneration

5.1. Microglial phagocytosis for neural homeostasis

Microglia are specialized macrophages in the central nervous system (CNS) and account for 10% of all the cells in the brain (Lyck et al., 2009). Microglial phagocytosis is critical to neurogenesis and normal brain function. Up to 50% of excess neurons are generated during neurogenesis, deleted through apoptosis and removed by microglial phagocytosis without triggering inflammation or autoimmune disorders (de la Rosa and de Pablo, 2000). Synaptic connections in the CNS are dynamic rather than static, and are constantly restructured by removal of neuronal processes via microglial phagocytosis (Paolicelli et al., 2011). The importance of microglial phagocytosis in the maintenance of CNS homeostasis and innate immune balance is highlighted by Nasu-Hakola disease, a chronic fatal neurodegeneration in which TREM2 phagocytic receptor is mutated (Neumann and Takahashi, 2007). The absence of TREM2 on microglia impaired their ability to phagocytose cellular debris and increased their gene transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Neumann and Takahashi, 2007).

5.2. Multiple sclerosis

Similar to macrophages, microglia are professional phagocytes that play an important role in autoimmunity of the CNS. Phagocytosis of neuronal debris contributes to augment of autoimmune response in MS (Huizinga et al., 2012). During the recovery phase of MS, however, microglial phagocytosis of apoptotic cells or myelin debris can generate an anti-inflammatory milieu that promotes neural regeneration (Napoli and Neumann, 2010). A recent study showed that polymorphisms in MerTK gene are associated with MS (Ma et al., 2011). Mice deficient in Gas6, a well-known MerTK ligand, showed compromised survival of oligodendrocytes, increased demyelination and reduced remyelination (Binder et al., 2008; Binder et al., 2011). Upregulation of the soluble MerTK receptor, which acts as a decoy to block Gas6 binding to the receptor, negatively correlated with Gas6 in established MS lesions. This suggests that dysregulation of protective Gas6-MerTK signaling may prolong MS activity (Weinger et al., 2009). These results suggest that microglial phagocytosis has an important role in MS pathogenesis and recovery.

Removal of myelin debris is a necessary process for neural repair. Compared with young rats, older rats with toxin-induced demyelination had a delayed recruitment of phagocytes and age-associated decrease in remyelination (Sim et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2006). Treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mice with TREM2 receptor-transduced phagocytes facilitated debris clearance and promoted neural repair and resolution of the inflammation (Takahashi et al., 2007).

We recently identified tubby as a new MerTK ligand (Caberoy et al., 2010b), which is expressed in the nervous system and can regulate microglial phagocytosis (Caberoy et al., 2012b). Mice with autosomal recessive mutation in tubby develop adult-onset obesity, retinal and cochlear degeneration by undefined molecular mechanisms (Noben-Trauth et al., 1996). Our data showed that young and aged microglia have similar tubby-mediated phagocytosis activity, suggesting that MerTK is an unlikely age-dependent pathway in microglia. This also illustrates the difficulty of identifying age-dependent phagocytosis pathways.

5.3. Age-related neurodegenerations

Microglial activation has been reported in a number of age-related neurodegenerations, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease (Luo et al., 2010; Pavese et al., 2006). Aging is known to impair microglial functions with increased susceptibility to pro-inflammatory activation (Luo et al., 2010; von Bernhardi et al., 2010), possibly through the mechanisms illustrated in Fig. 2.

Two recent studies reported that a TREM2 variant (R47H) is associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Guerreiro et al., 2013; Jonsson et al., 2013). Given the critical role of TREM2 in anti-inflammatory phagocytosis by microglia (Hsieh et al., 2009; Neumann and Daly, 2013), it is not surprising that the TREM2 variant may lead to an increased predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease.

Microglial phagocytosis plays an important role in the clearance of amyloid β peptide (Aβ) (Lee and Landreth, 2010). One of the well-known mechanisms for microglial clearance of Aβ is through antibody-mediated pathways (Morgan, 2009). Microglia from aged mice internalized less Aβ than microglia from neonatal or young mice (Njie et al., 2012). Compared to age-matched wild-type littermate controls, microglia from genetically-engineered aged mice with Alzheimer’s disease have a 2-5-fold decrease in expression of the Aβ-binding SRs, such as scavenger receptor A (SRA), CD36 and RAGE (Hickman et al., 2008). Whether phagocytosed fibrillar forms of Aβ (fAβ) can be degraded intracellularly remains controversial. It was argued that resident microglia with the most direct access to parenchymal fAβ has a limited capacity to phagocytose fAβ (Lai and McLaurin, 2012). Instead peripheral macrophages with limited access to the CNS can more readily phagocytose and degrade fAβ. To what extend microglial or macrophage aging may contribute to the formation of amyloid plaques in the brain remains an unanswered question.

6. RPE dysfunction and AMD

6.1. The roles of RPE phagocytosis

Unlike macrophages and microglia, the RPE cells are non-professional phagocytes, but are critical for visual function. The photoreceptor outer segments (POSs) not only convert light to electric impulses, but are susceptible to photo- and oxidative damage. The POSs renew themselves by shedding packets of POSs at their tips in a diurnal rhythm. Shed POSs are removed and recycled through RPE phagocytosis. Based on the turnover rate of POSs, it was predicted that the RPE can phagocytose approximately 75-fold of its own volume every year (Li, 2012a) and therefore is one of the most active phagocytes in our body. Defect of PRE phagocytosis, such as MerTK mutations, resulted in accumulation of unphagocytosed POS debris, retinal degeneration and blindness in humans and animal models (D’Cruz et al., 2000; Gal et al., 2000; Scott et al., 2001). In this regard, RPE phagocytosis is critical to retinal homeostasis and photoreceptor function. Of the five known MerTK ligands (Caberoy et al., 2012a; Caberoy et al., 2010b; Stitt et al., 1995), autosomal recessive mutations of either tubby or Tulp1 cause retinal degeneration, albeit without the accumulation of unphagocytosed debris as in the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) rats with MerTK mutation (Dowling and Sidman, 1962; Hagstrom et al., 1999; Stubdal et al., 2000). An unsolved question is which MerTK ligand is essential to prevent retinal degeneration.

Another important role of RPE phagocytosis is to promote cell survival. Bazan and colleagues reported that RPE phagocytosis can convert phagocytosed docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to anti-apoptotic molecule neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1), thereby promoting the survival of RPE and photoreceptors against oxidative stress (Bazan et al., 2010; Mukherjee et al., 2007; Mukherjee et al., 2004). DHA is one of the essential omega-3 fatty acids that cannot be synthesized de novo in vivo. POSs have the highest level of DHA in our body (Bazan, 2006). In addition, MerTK signaling also promotes phagocyte survival against oxidative stress (Anwar et al., 2009). Similarly, other studies suggest that MerTK signaling is important for cell survival (Shiozawa et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013). Therefore, RPE phagocytosis is critical not only to retinal homeostasis through debris clearance but also to RPE survival via NPD1 synthesis and MerTK signaling.

6.2. Retinal aging, RPE phagocytosis dysfunction and AMD pathogenesis

The RPE plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of AMD, which is the leading cause of blindness in the elderly in developed countries (Friedman et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2001). AMD has two forms: the wet (exudative) and dry (atrophic) AMD (Jager et al., 2008). Atrophic AMD accounts for ~80–90% of the disease and still lacks a FDA-approved therapy. Early stage of AMD is characterized by drusen, which are yellow deposits present in the sub-RPE space of the aged retina. How drusen are formed remains elusive. Some believed that drusen may be unphagocytosed debris that translocates from the apical to sub-RPE region (Zhao et al., 2007). Others proposed that drusen may be the result of RPE exocytosis of undegradable phagocytosed materials (Kinnunen et al., 2012). Proteomics analysis showed that drusen mainly consists of different proteins, many of which are modified with oxidation, lipoxidation or crosslinking (Crabb et al., 2002). Advanced dry AMD is characterized by geographic atrophy, in which the RPE undergoes apoptotic cell loss and is no longer capable of supporting the normal function of photoreceptors (Ding et al., 2009; Jager et al., 2008).

Retinal aging has a significant impact on RPE phagocytosis. For example, RPE phagocytosis was reduced by ~80% in aged rats (Katz and Robison, 1984). The RPE and choroid of aged animals showed iron accumulation, and exposure of RPE cells to increased iron markedly reduced their phagocytosis activity (Chen et al., 2009). Consequently, an age-dependent phagocytosis activity reduction may not only disrupt retinal homeostasis but also affect RPE survival, leading to RPE apoptotic loss, photoreceptor degeneration and AMD. Delineation of age-dependent phagocytosis pathways is crucial to understanding molecular mechanisms of AMD pathogenesis and developing anti-aging therapy to promote RPE survival.

6.3. Microglia and AMD

Besides the RPE, phagocytosis by macrophages or microglia is also important to AMD pathogenesis. Infiltrated macrophages are often coupled with drusen in AMD retina (Ding et al., 2009), possibly because drusen send chemotactic signals to recruit the professional phagocytes for debris clearance. AMD is now widely regarded as an inflammatory disease (Buschini et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2009). Defects in macrophage chemotaxis, including deletion of chemotactic factor Ccl2 or receptors (e.g., Ccr2 or CX3CR1) in mice, caused AMD-like symptoms (Ambati et al., 2003; Combadiere et al., 2007).

7. Phagocyte aging and other cellular alternations

Although yet to be characterized in detail, it is known that phagocyte aging shares many similarities to regular cell aging. This includes age-related epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, which may alter the transcriptome profile (Hannum et al., 2013). Dysregulation of microRNAs, such as MiR-146a, contributes to age-related dysfunction of macrophages (Jiang et al., 2012). Mitochondrial dysfunction has been linked to tissue aging (Yen et al., 1989), and somatic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations increase with age (Corral-Debrinski et al., 1992). Lysosomal disturbances have been linked to altered amyloid precursor protein processing in Alzheimer’s disease (Cataldo et al., 1996). Accumulated lipofuscin, which is the product of oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, impairs RPE phagocytosis (Vives-Bauza et al., 2008). Oxidative stress has been implicated in phagocyte aging and damage (de la Fuente et al., 2004; Videla et al., 2001).

8. Challenges and opportunities to unravel the molecular mystery of phagocyte aging and dysfunction

8.1. Bottlenecks

To date, most efforts to investigate age-related phagocyte dysfunction are mainly focused on the characterization of phagocytosis activity loss. Molecular mechanisms of phagocyte dysfunction have not been investigated. The entire field of phagocyte senescence at the molecular levels remains a big enigma because of the following two bottlenecks. First, nearly all the known phagocytosis signaling pathways, including phagocytosis ligands, receptors and intracellular signaling cascades, were identified on a case-by-case basis with daunting technical challenges. Some of the identified pathways are discussed in a recent review (Li, 2012a). Despite enormous efforts by many groups, we still do not known how many new phagocytosis pathways are yet to be identified and which ones are more important. Second, in contrast to MerTK or TREM2 mutations with complete ablation of a single pathway, phagocyte aging may progressively reduce the activity of multiple pathways. Identification of age-dependent phagocytosis pathways requires quantification and comparison of their functional activity between young and aged phagocytes. Given the current inability of activity quantification by conventional approaches, no single age-dependent phagocytosis pathway has been identified. Therefore, age-related phagocyte dysfunction is an ambiguous concept at the molecular level.

8.2. Unbiased identification of phagocytosis ligands

To tackle the bottlenecks, we have developed phagocytosis-based functional cloning (PFC) for unbiased identification of phagocytosis ligands in the absence of receptor information (Caberoy et al., 2010a; Li, 2012a). PFC is a new technology derived from open reading frame (ORF) phage display (Li, 2012b). The validity of PFC to identify biologically relevant ligands was demonstrated by identifying and independently characterizing Tulp1 and tubby as new MerTK ligands (Caberoy et al., 2010b). Moreover, we developed dual functional cloning (DFC) for unbiased identification of receptor-specific phagocytosis ligands (Caberoy et al., 2012a; Li, 2012a). The validity of DFC was highlighted by the identification and characterization of Gal-3 as a new MerTK ligand. As a result, the first bottleneck has been effectively solved by PFC technology.

8.3 Activity quantification

It is worth noting that individual ligands identified by PFC can be further quantified for their functional activities by “phage phagocytosis assay”. In one of our studies, we isolated 22 clones from enriched phages, quantified their activities in RPE cells by a phagocytosis assay and identified 5 clones with higher internalization activity (Caberoy et al., 2010a). Using this approach, we successfully identified 9 putative phagocytosis ligands with higher internalization activity than control phage (Caberoy et al., 2010a). Moreover, we also constructed a panel of phage clones displaying Tulp1 with deletions or mutations to map its structure-function relationship by the phagocytosis assay. We effectively defined five K/R(X)1-2KKK consensus motifs in the N-terminus of Tulp1 as minimal MerTK-binding motifs (Caberoy et al., 2010b). These studies showed that phagocytosis ligands can be reliably quantified for activity comparison. Conceivably, we can use the same approach of the phagocytosis assay to quantify ligand activities in young and aged phagocytes. Using this approach, we have identified dozens of putative phagocytosis ligands that are functionally more active in neonatal microglia or RPE than in aged phagocytes (unpublished data). Thus, this approach will eventually lead to systematic identification of age-dependent phagocytosis ligands for different phagocytes. The identified ligands can be used as molecular probes to further delineate their receptors and intracellular signaling cascades to decipher the molecular mystery of phagocyte aging and dysfunction (Caberoy et al., 2010b; Li, 2012a).

9. Conclusions

A growing body of evidence suggests that phagocyte dysfunction in aged tissues will lead to accumulation of unphagocytosed debris, deterioration of tissue homeostasis, imbalance of innate immune response, chronic sterile inflammation, and accelerated tissue damage and degeneration. Lack of knowledge on the molecular mechanisms of phagocyte aging has hindered our capability of developing anti-aging therapy by modulating phagocyte activity and preventing age-related tissue damage. New research tools developed in the past few years has enabled systematic identification of phagocytosis ligands in the absence of receptor information and reliable quantification of their functional activities. Quantitative comparison for young vs. aged phagocytes will identify age-dependent phagocytosis ligands and their signaling pathways. These will unravel the molecular mystery of phagocyte aging and dysfunction. Future therapies targeting age-dependent pathways can be developed to promote phagocyte function, restore tissue homeostasis and prevent or delay tissue degeneration.

Highlights.

Phagocytosis is critical to tissue homeostasis and innate immune balance.

Aging leads to phagocyte dysfunction with debris accumulation and inflammation.

Phagocyte aging exacerbates tissue damage through multiple mechanisms.

New approaches to delineate age-dependent phagocytosis pathways are discussed.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Duco Hamasaki for manuscript review. This work is partially supported by NIH R01GM094449, R21HD075372 and grants from Florida James & Esther King Biomedical Research Program (1KF-38241), BrightFocus Foundation (M2012026), Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (5-2012-189), Glaucoma Research Foundation and Florida Bankhead-Coley Cancer Research Program (2BF-04-46776).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Cao JN, Su H, Osann K, Gupta S. Altered innate immune functioning of dendritic cells in elderly humans: a role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2007;178:6912–6922. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambati J, Anand A, Fernandez S, Sakurai E, Lynn BC, Kuziel WA, Rollins BJ, Ambati BK. An animal model of age-related macular degeneration in senescent Ccl-2- or Ccr-2-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2003;9:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar A, Keating AK, Joung D, Sather S, Kim GK, Sawczyn KK, Brandao L, Henson PM, Graham DK. Mer tyrosine kinase (MerTK) promotes macrophage survival following exposure to oxidative stress. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:73–79. doi: 10.1189/JLB.0608334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aprahamian T, Takemura Y, Goukassian D, Walsh K. Ageing is associated with diminished apoptotic cell clearance in vivo. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2008;152:448–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology. 2007;120:435–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquer NZ, Taha A, Kumar P, McLean P, Cowsik SM, Kale RK, Singh R, Sharma D. A metabolic and functional overview of brain aging linked to neurological disorders. Biogerontology. 2009;10:377–413. doi: 10.1007/s10522-009-9226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG. Cell survival matters: docosahexaenoic acid signaling, neuroprotection and photoreceptors. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG, Calandria JM, Serhan CN. Rescue and repair during photoreceptor cell renewal mediated by docosahexaenoic acid-derived neuroprotectin D1. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:2018–2031. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R001131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder MD, Cate HS, Prieto AL, Kemper D, Butzkueven H, Gresle MM, Cipriani T, Jokubaitis VG, Carmeliet P, Kilpatrick TJ. Gas6 deficiency increases oligodendrocyte loss and microglial activation in response to cuprizone-induced demyelination. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5195–5206. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1180-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder MD, Xiao J, Kemper D, Ma GZ, Murray SS, Kilpatrick TJ. Gas6 increases myelination by oligodendrocytes and its deficiency delays recovery following cuprizone-induced demyelination. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschini E, Piras A, Nuzzi R, Vercelli A. Age related macular degeneration and drusen: neuroinflammation in the retina. Progress in neurobiology. 2011;95:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher SK, Chahal H, Nayak L, Sinclair A, Henriquez NV, Sapey E, O’Mahony D, Lord JM. Senescence in innate immune responses: reduced neutrophil phagocytic capacity and CD16 expression in elderly humans. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:881–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caberoy NB, Alvarado G, Bigcas JL, Li W. Galectin-3 is a new MerTK-specific eat-me signal. J Cell Physiol. 2012a;227:401–407. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caberoy NB, Alvarado G, Li W. Tubby regulates microglial phagocytosis through MerTK. J Neuroimmunol. 2012b doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.07.009. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Caberoy NB, Maiguel D, Kim Y, Li W. Identification of tubby and tubby-like protein 1 as eat-me signals by phage display. Exp Cell Res. 2010a;316:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caberoy NB, Zhou Y, Li W. Tubby and tubby-like protein 1 are new MerTK ligands for phagocytosis. EMBO J. 2010b;29:3898–3910. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Hamilton DJ, Barnett JL, Paskevich PA, Nixon RA. Properties of the endosomal-lysosomal system in the human central nervous system: disturbances mark most neurons in populations at risk to degenerate in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1996;16:186–199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00186.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:826–837. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lukas TJ, Du N, Suyeoka G, Neufeld AH. Dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelium with age: increased iron decreases phagocytosis and lysosomal activity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1895–1902. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combadiere C, Feumi C, Raoul W, Keller N, Rodero M, Pezard A, Lavalette S, Houssier M, Jonet L, Picard E, Debre P, Sirinyan M, Deterre P, Ferroukhi T, Cohen SY, Chauvaud D, Jeanny JC, Chemtob S, Behar-Cohen F, Sennlaub F. CX3CR1-dependent subretinal microglia cell accumulation is associated with cardinal features of age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2920–2928. doi: 10.1172/JCI31692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Debrinski M, Horton T, Lott MT, Shoffner JM, Beal MF, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA deletions in human brain: regional variability and increase with advanced age. Nat Genet. 1992;2:324–329. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb JW, Miyagi M, Gu X, Shadrach K, West KA, Sakaguchi H, Kamei M, Hasan A, Yan L, Rayborn ME, Salomon RG, Hollyfield JG. Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14682–14687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222551899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz PM, Yasumura D, Weir J, Matthes MT, Abderrahim H, LaVail MM, Vollrath D. Mutation of the receptor tyrosine kinase gene Mertk in the retinal dystrophic RCS rat. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:645–651. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente M, Hernanz A, Guayerbas N, Alvarez P, Alvarado C. Changes with age in peritoneal macrophage functions. Implication of leukocytes in the oxidative stress of senescence. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2004;50 Online Pub:OL683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa EJ, de Pablo F. Cell death in early neural development: beyond the neurotrophic theory. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:454–458. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01628-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Patel M, Chan CC. Molecular pathology of age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling JE, Sidman RL. Inherited retinal dystrophy in the rat. J Cell Biol. 1962;14:73–109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.14.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwig LP, Henson PM. Immunological consequences of apoptotic cell phagocytosis. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:2–8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, Giunta S, Olivieri F, Sevini F, Panourgia MP, Invidia L, Celani L, Scurti M, Cevenini E, Castellani GC, Salvioli S. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman GJ, Casasnovas JM, Umetsu DT, DeKruyff RH. TIM genes: a family of cell surface phosphatidylserine receptors that regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:172–189. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00903.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker M, Neher JJ, Zhao JW, Thery C, Tolkovsky AM, Brown GC. MFG-E8 mediates primary phagocytosis of viable neurons during neuroinflammation. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2657–2666. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4837-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Munoz B, Tomany SC, McCarty C, de Jong PT, Nemesure B, Mitchell P, Kempen J. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal A, Li Y, Thompson DA, Weir J, Orth U, Jacobson SG, Apfelstedt-Sylla E, Vollrath D. Mutations in MERTK, the human orthologue of the RCS rat retinal dystrophy gene, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 2000;26:270–271. doi: 10.1038/81555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Immune aging and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:1615–1623. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0970-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo MA, Colombatto S. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs): involvement in aging and in neurodegenerative diseases. Amino Acids. 2008;35:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe JS, Younkin S, Hazrati L, Collinge J, Pocock J, Lashley T, Williams J, Lambert JC, Amouyel P, Goate A, Rademakers R, Morgan K, Powell J, St George-Hyslop P, Singleton A, Hardy J. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:117–127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagstrom SA, Duyao M, North MA, Li T. Retinal degeneration in tulp1−/− mice: vesicular accumulation in the interphotoreceptor matrix. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2795–2802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannum G, Guinney J, Zhao L, Zhang L, Hughes G, Sadda S, Klotzle B, Bibikova M, Fan JB, Gao Y, Deconde R, Chen M, Rajapakse I, Friend S, Ideker T, Zhang K. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol Cell. 2013;49:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Kubo H, Morimoto K, Fujino N, Suzuki T, Takahasi T, Yamada M, Yamaya M, Maekawa T, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H. Receptor for advanced glycation end products binds to phosphatidylserine and assists in the clearance of apoptotic cells. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:358–364. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, Cheng WJ, Maisa A, Landay AL, Jaworowski A, Crowe SM. Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging cell. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8354–8360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CL, Koike M, Spusta SC, Niemi EC, Yenari M, Nakamura MC, Seaman WE. A role for TREM2 ligands in the phagocytosis of apoptotic neuronal cells by microglia. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1144–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga R, van der Star BJ, Kipp M, Jong R, Gerritsen W, Clarner T, Puentes F, Dijkstra CD, van der Valk P, Amor S. Phagocytosis of neuronal debris by microglia is associated with neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Glia. 2012;60:422–431. doi: 10.1002/glia.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi T, Murata T, Hangai M, Nagai R, Horiuchi S, Lopez PF, Hinton DR, Ryan SJ. Advanced glycation end products in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1629–1632. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.12.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan E, Colovai AI. Human Fc receptors: critical targets in the treatment of autoimmune diseases and transplant rejections. Human immunology. 2006;67:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager RD, Mieler WF, Miller JW. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2606–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Xiang Y, Wang D, Gao J, Liu D, Liu Y, Liu S, Zheng D. Dysregulated expression of miR-146a contributes to age-related dysfunction of macrophages. Aging cell. 2012;11:29–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, Bjornsson S, Huttenlocher J, Levey AI, Lah JJ, Rujescu D, Hampel H, Giegling I, Andreassen OA, Engedal K, Ulstein I, Djurovic S, Ibrahim-Verbaas C, Hofman A, Ikram MA, van Duijn CM, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:107–116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz ML, Robison WG., Jr Age-related changes in the retinal pigment epithelium of pigmented rats. Exp Eye Res. 1984;38:137–151. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(84)90098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen K, Petrovski G, Moe MC, Berta A, Kaarniranta K. Molecular mechanisms of retinal pigment epithelium damage and development of age-related macular degeneration. Acta ophthalmologica. 2012;90:299–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai AY, McLaurin J. Clearance of amyloid-beta peptides by microglia and macrophages: the issue of what, when and where. Future neurology. 2012;7:165–176. doi: 10.2217/fnl.12.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Landreth GE. The role of microglia in amyloid clearance from the AD brain. J Neural Transm. 2010;117:949–960. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke G, Rothlin CV. Immunobiology of the TAM receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:327–336. doi: 10.1038/nri2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. Eat-me signals: Keys to molecular phagocyte biology and “Appetite” control. J Cell Physiol. 2012a;227:1291–1297. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. ORF phage display to identify cellular proteins with different functions. Methods. 2012b;58:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo XG, Ding JQ, Chen SD. Microglia in the aging brain: relevance to neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyck L, I, Santamaria D, Pakkenberg B, Chemnitz J, Schroder HD, Finsen B, Gundersen HJ. An empirical analysis of the precision of estimating the numbers of neurons and glia in human neocortex using a fractionator-design with sub-sampling. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;182:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma GZ, Stankovich J, Kilpatrick TJ, Binder MD, Field J. Polymorphisms in the receptor tyrosine kinase MERTK gene are associated with multiple sclerosis susceptibility. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda L, Cassatella MA, Szendrei GI, Otvos L, Jr, Baron P, Villalba M, Ferrari D, Rossi F. Activation of microglial cells by beta-amyloid protein and interferon-gamma. Nature. 1995;374:647–650. doi: 10.1038/374647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyanishi M, Tada K, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kitamura T, Nagata S. Identification of Tim4 as a phosphatidylserine receptor. Nature. 2007;450:435–439. doi: 10.1038/nature06307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. The role of microglia in antibody-mediated clearance of amyloid-beta from the brain. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets. 2009;8:7–15. doi: 10.2174/187152709787601821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee PK, Marcheselli VL, de Rivero Vaccari JC, Gordon WC, Jackson FE, Bazan NG. Photoreceptor outer segment phagocytosis attenuates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis with concomitant neuroprotectin D1 synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13158–13163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705963104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee PK, V, Marcheselli L, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. Neuroprotectin D1: a docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8491–8496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402531101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli I, Neumann H. Microglial clearance function in health and disease. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1030–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli I, Neumann H. Protective effects of microglia in multiple sclerosis. Exp Neurol. 2010;225:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H, Daly MJ. Variant TREM2 as risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:182–184. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1213157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H, Takahashi K. Essential role of the microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 (TREM2) for central nervous tissue immune homeostasis. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njie EG, Boelen E, Stassen FR, Steinbusch HW, Borchelt DR, Streit WJ. Ex vivo cultures of microglia from young and aged rodent brain reveal age-related changes in microglial function. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:195 e191–112. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noben-Trauth K, Naggert JK, North MA, Nishina PM. A candidate gene for the mouse mutation tubby. Nature. 1996;380:534–538. doi: 10.1038/380534a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolicelli RC, Bolasco G, Pagani F, Maggi L, Scianni M, Panzanelli P, Giustetto M, Ferreira TA, Guiducci E, Dumas L, Ragozzino D, Gross CT. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science. 2011;333:1456–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Tosello-Trampont AC, Elliott MR, Lu M, Haney LB, Ma Z, Klibanov AL, Mandell JW, Ravichandran KS. BAI1 is an engulfment receptor for apoptotic cells upstream of the ELMO/Dock180/Rac module. Nature. 2007;450:430–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Jung MY, Kim HJ, Lee SJ, Kim SY, Lee BH, Kwon TH, Park RW, Kim IS. Rapid cell corpse clearance by stabilin-2, a membrane phosphatidylserine receptor. Cell death and differentiation. 2008;15:192–201. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavese N, Gerhard A, Tai YF, Ho AK, Turkheimer F, Barker RA, Brooks DJ, Piccini P. Microglial activation correlates with severity in Huntington disease: a clinical and PET study. Neurology. 2006;66:1638–1643. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000222734.56412.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plowden J, Renshaw-Hoelscher M, Engleman C, Katz J, Sambhara S. Innate immunity in aging: impact on macrophage function. Aging cell. 2004;3:161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AM, Hori O, Chen JX, Li JF, Crandall J, Zhang J, Cao R, Yan SD, Brett J, Stern D. Advanced glycation endproducts interacting with their endothelial receptor induce expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in cultured human endothelial cells and in mice. A potential mechanism for the accelerated vasculopathy of diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1395–1403. doi: 10.1172/JCI118175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM. The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:949–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI14002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RS, McMahon EJ, Pop SM, Reap EA, Caricchio R, Cohen PL, Earp HS, Matsushima GK. Phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells is mediated by MER. Nature. 2001;411:207–211. doi: 10.1038/35075603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa Y, Pedersen EA, Taichman RS. GAS6/Mer axis regulates the homing and survival of the E2A/PBX1-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the bone marrow niche. Experimental hematology. 2010;38:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim FJ, Zhao C, Penderis J, Franklin RJ. The age-related decrease in CNS remyelination efficiency is attributable to an impairment of both oligodendrocyte progenitor recruitment and differentiation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2451–2459. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02451.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simell B, Vuorela A, Ekstrom N, Palmu A, Reunanen A, Meri S, Kayhty H, Vakevainen M. Aging reduces the functionality of anti-pneumococcal antibodies and the killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae by neutrophil phagocytosis. Vaccine. 2011;29:1929–1934. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims GP, Rowe DC, Rietdijk ST, Herbst R, Coyle AJ. HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:367–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W, Assink J, Klein R, Mitchell P, Klaver CC, Klein BE, Hofman A, Jensen S, Wang JJ, de Jong PT. Risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: Pooled findings from three continents. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:697–704. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00580-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solana R, Tarazona R, Gayoso I, Lesur O, Dupuis G, Fulop T. Innate immunosenescence: Effect of aging on cells and receptors of the innate immune system in humans. Seminars in immunology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.008. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt TN, Conn G, Gore M, Lai C, Bruno J, Radziejewski C, Mattsson K, Fisher J, Gies DR, Jones PF, et al. The anticoagulation factor protein S and its relative, Gas6, are ligands for the Tyro 3/Axl family of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1995;80:661–670. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubdal H, Lynch CA, Moriarty A, Fang Q, Chickering T, Deeds JD, Fairchild-Huntress V, Charlat O, Dunmore JH, Kleyn P, Huszar D, Kapeller R. Targeted deletion of the tub mouse obesity gene reveals that tubby is a loss-of-function mutation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:878–882. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.878-882.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Prinz M, Stagi M, Chechneva O, Neumann H. TREM2-transduced myeloid precursors mediate nervous tissue debris clearance and facilitate recovery in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS medicine. 2007;4:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videla LA, Tapia G, Fernandez V. Influence of aging on Kupffer cell respiratory activity in relation to particle phagocytosis and oxidative stress parameters in mouse liver. Redox report : communications in free radical research. 2001;6:155–159. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Bauza C, Anand M, Shirazi AK, Magrane J, Gao J, Vollmer-Snarr HR, Manfredi G, Finnemann SC. The age lipid A2E and mitochondrial dysfunction synergistically impair phagocytosis by retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24770–24780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800706200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassara H, Li YM, Imani F, Wojciechowicz D, Yang Z, Liu FT, Cerami A. Identification of galectin-3 as a high-affinity binding protein for advanced glycation end products (AGE): a new member of the AGE-receptor complex. Mol Med. 1995;1:634–646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bernhardi R, Tichauer JE, Eugenin J. Aging-dependent changes of microglial cells and their relevance for neurodegenerative disorders. J Neurochem. 2010;112:1099–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Moncayo G, Morin P, Jr, Xue G, Grzmil M, Lino MM, Clement-Schatlo V, Frank S, Merlo A, Hemmings BA. Mer receptor tyrosine kinase promotes invasion and survival in glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogene. 2013;32:872–882. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinger JG, Omari KM, Marsden K, Raine CS, Shafit-Zagardo B. Up-regulation of soluble Axl and Mer receptor tyrosine kinases negatively correlates with Gas6 in established multiple sclerosis lesions. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:283–293. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenisch C, Patruta S, Daxbock F, Krause R, Horl W. Effect of age on human neutrophil function. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:40–45. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TC, Chen YS, King KL, Yeh SH, Wei YH. Liver mitochondrial respiratory functions decline with age. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:944–1003. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Li WW, Franklin RJ. Differences in the early inflammatory responses to toxin-induced demyelination are associated with the age-related decline in CNS remyelination. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Wang Z, Liu Y, Song Y, Li Y, Laties AM, Wen R. Translocation of the retinal pigment epithelium and formation of sub-retinal pigment epithelium deposit induced by subretinal deposit. Mol Vis. 2007;13:873–880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]