1. Introduction

Nutrition and cancer research relies on dietary data collected from the general population and experimental subjects to assess associations between dietary components and cancer risk, but these techniques have several limitations, including underreporting and measurement error on the part of the subject or researcher, in addition to variation in food composition due to growing conditions and genetics (Davis and Milner, 2007). Therefore, research laboratories, including ours, are currently developing urinary biomarkers for bioactive components found in cruciferous and apiaceous vegetables.

Cruciferous vegetables, including broccoli and Brussels sprouts, contain glucosinolates such as glucobrassicin which release the hydrolysis product indole-3-carbinol (I3C) upon consumption. I3C has cancer chemopreventive effects, based on studies in cell culture and animal models (Aggarwal and Ichikawa, 2005; Fenwick and Heaney, 1983; Hwang et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Marconett et al., 2011; Qian et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012; Weng et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2011). However, the lack of an objective biomarker has limited epidemiologic research on I3C in human populations. Following consumption, I3C dimerizes or oligomerizes under the acidic conditions in the stomach, leading to the formation of several compounds, of which 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) is the most prevalent (structure shown in Figure 1); therefore DIM has been considered a promising candidate for an I3C biomarker (Anderton et al., 2004; Reed et al., 2006; Reed et al., 2005; Stresser et al., 1995).

Figure 1.

Structures of the contaminants DIM (A), 8-MOP (B), and 5-MOP (C) analyzed in this study. The respective internal standards for each analyte utilized deuterium (‘D’) instead of hydrogen atoms at the specified positions.

Apiaceous vegetables, which include carrots, parsley, and parsnips, contain furanocoumarins, bioactive molecules that inhibit the activities of cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP) 1A1, 1A2, 2A6, and 3A4, thereby reducing the activation of pro-carcinogens (Kang et al., 2011; Kleiner et al., 2002; Koenigs et al., 1997; Lampe et al., 2000; Naritomi et al., 2004; Peterson et al., 2006; Prince et al., 2006; Sellers et al., 2003; Tassaneeyakul et al., 2000). Each of these enzymes activate several pro-carcinogens, thus even modest inhibition of them by plant foods may be a potential means of chemoprevention of cancer. However, the inhibition of CYP 3A4 by furanocoumarins (including those found in grapefruit juice) may interact with pharmaceuticals such as cyclosporine, lovastatin, and felodipine, increasing the risk of toxic exposures to these drugs (Paine et al., 2006). An objective measurement of furanocoumarin exposure from apiaceous vegetables or grapefruit juice would be advantageous for chemoprevention as well as pharmaceutical safety research. Given their levels in apiaceous vegetables and previous studies detailing their pharmacokinetics due to pharmacologic uses, 5-methoxypsoralen (5-MOP) and 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP) are candidate furanocoumarins as biomarkers of dietary exposure (structures shown in Figure 1).

A common feature of dietary bioactives is their in vivo conjugation via phase II enzymes, particularly UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), resulting in the excretion of glucuronidated compounds in the urine (John et al., 1992; Messer et al., 2011; Tukey and Strassburg, 2000). Sulfonated conjugates may represent additional urinary forms of these biomarkers (Gamage et al., 2006; Staub et al., 2006). Consequently, enzyme formulations containing both glucuronidase and sulfatase activities have been employed in the development of urinary biomarker assays for furanocoumarins and DIM. The use of Helix pomatia (snail) digestive juice as a source of these enzymes is a common sample preparation technique but has proven problematic during the development of these dietary biomarkers. While validating the biomarker methods in our studies, it became evident that H2O blanks treated only with the enzyme mixture and internal standards yielded detectable levels of DIM, 5-MOP, and 8-MOP. Because of the frequent experimental use of this enzyme formulation, it is imperative to inform the research community of its potential for contamination with numerous dietary components. The objectives of this brief communication were to characterize the contamination of H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase with DIM, 5-MOP, and 8-MOP and identify an alternative source of the enzyme.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals were HPLC, LC-MS, or Optima grade. DIM was purchased from LKT Labs (St. Paul, MN), indole and t-butyl methyl ether were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and d2-formaldehyde (isotopic purity 98%) was procured from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA). LC-MS H2O was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and methanol, acetonitrile, hexane, ethyl acetate, isopropanol, and acetic acid were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA). β-Glucuronidase/arylsulfatase from Helix pomatia (cat. no. 10127698001) was purchased from Roche (Penzberg, Germany). β-Glucuronidase preparations of various purity levels from H. pomatia (G7017, G0751, and G1512) and Escherichia coli (G8295) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline 1X was purchased from Gibco by Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Deuterated internal standards 8-MOP-d3 and 5-MOP-d3 were obtained from TLC Pharmachem (Vaughan, Ontario, Canada). Nitrogen gas was high purity grade, 99.998% (Matheson Gas, Basking Ridge, NJ). D2-DIM was synthesized as previously described (Jackson et al., 1987).

2.2. DIM analysis: Treatment of H2O with H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase

To establish that H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase (Roche cat. no. 10127698001, lot no. 70255323) was the source of DIM contamination, 1 mL of HPLC grade H2O was treated with 1000, 2000, 4000, or 6000 U of the enzyme and 10 pmol of d2-DIM as an internal standard. Additional samples were treated with 2000 U of a different lot number of the same enzyme (Roche cat. no. 10127698001, lot no. 70331220) or 2000 U of E. coli β-glucuronidase (Sigma G8295) solution in phosphate buffered saline (0.26%, w/v) and internal standard. Each sample was extracted two times with an equal volume of t-butyl methyl ether. The extracts were evaporated to dryness and reconstituted to 20 μL with acetonitrile/10mM ammonium acetate (30/70, v/v).

2.3. Quantitation of DIM by capillary LC-ESI-MS/MS-SRM

The analyses were carried out by capillary liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry-selected reaction monitoring (LC-ESI-MS/MS-SRM) on a TSQ Quantum Discovery Max instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in the positive ion mode with N2 as the nebulizing and drying gas. Mass spectrometry (MS) parameters were set as follows: spray voltage, 32 kV; sheath gas pressure, 25; capillary temperature, 250 °C; collision energy, 17 V; scan width, 0.05 amu; Q2 gas pressure 1.0 mTorr; source CID 9 V; and tube lens offset, 104 V. MS data were acquired and processed by Xcalibur software version 1.4 (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA). Eight microliters of the sample were injected from an autosampler into the ESI source using an Agilent 1100 capillary HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a 5μm, 150 × 0.5 mm ZorbaxSB-C18 column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) eluted at 15 μl/min for the first 3 min then 10 μl/min with a gradient from 60% methanol in 15 mM NH4OAc to 100% methanol in 8 min and held for additional 29 min. The mass transitions (parent to daughter) monitored were m/z 247.12 → 130.07 for DIM (typical retention time of 16.6 min) and m/z 249.12 → 132.07 for d2-DIM (typical retention time of 16.5 min) as an internal standard. Quantitation was accomplished by comparing the MS peak area ratio of DIM to that of the deuterated standard with a calibration curve of the concentration of DIM versus the MS peak area ratio (DIM:internal standard). The assay limit of quantitation (LOQ) was 132 fmol.

2.4. Furanocoumarin analysis: Assessment of contamination in crude and refined H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase

All powdered enzymes were made to approximately 120,000 U/mL in H2O and sonicated for 5 min. Each sample was prepared by adding 3000 U of enzyme to 750 μL LC-MS H2O and 750 fmol of both internal standards (8-MOP-d3 and 5-MOP-d3), followed by 5 min sonication. Blank samples contained only H2O. Samples were extracted using Trace N SPE columns (10 mg/1 mL) on a System 96 II positive pressure manifold from SPEware (Baldwin Park, CA). SPE columns were conditioned with 200 μL methanol and equilibrated with 200 μL H2O. After the samples were loaded, columns were washed with 1 mL LC-MS H2O and 250 μL 85/15 (v/v) H2O/isopropanol, followed by drying under N2 for 8 min. Analytes were eluted with 800 μL 80/20 (v/v) hexane/ethyl acetate, and eluates were evaporated to dryness under N2 at 40 °C. Extracts were reconstituted in 50 μL 10/90 (v/v) methanol/H2O. To ensure full dissolution, reconstituted extracts were vortexed for 15 seconds, centrifuged for 1 min at 1700 × g, sonicated for 5 min, and centrifuged again for 5 min at 1700 × g.

2.5. Quantitation of 8-MOP and 5-MOP by LC-APCI-MS/MS-SRM

Enzyme extracts (40 μL) were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis using an Agilent 1100 analytical HPLC (Palo Alto, CA) coupled to a TSQ Quantum Discovery mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were acquired and processed with Xcalibur software (v1.4, Thermo Electron). Isocratic LC separations were performed on a Restek (Bellefonte, PA) Ultra II Aromax column (150 × 3.2 mm i.d., 3 μm) at 600 μL/min and 50 °C, utilizing 45/15/40 methanol/acetonitrile/H2O (v/v/v) with 0.1% acetic acid as the mobile phase. Eluent was sent to waste for the first 4 min of each run and was then introduced into the MS using a Thermo Ion Max source in APCI mode. Ionization parameters were: corona voltage, 4000 V; discharge current, 4.0 μA; vaporizer temperature, 340 °C; sheath gas pressure, 17 (N2, arbitrary units); auxiliary gas pressure, 17 (N2, arbitrary); capillary temperature, 250 °C; capillary offset, 35 V; tube lens offset, 100 V; skimmer offset, −9 V; argon collision pressure, 1.6 mtorr. Typical retention times for 8-MOP and 8-MOP-d3 were 5.4 min, and those for 5-MOP and 5-MOP-d3 were 8.5 min. The nominal mass transitions m/z 217 → 90 (analytes) and m/z 220 → 90 (internal standards) were monitored in SRM mode for quantitation (collision energy = 32 eV), while m/z 217 → 174 and m/z 220 → 174 were monitored for confirmation (CE = 37 eV). Linear calibration curves with 1/x weighting were constructed in Xcalibur after plotting the peak area ratio of each analyte to its internal standard (STD:ISTD) vs. analyte concentration. Quantitation was performed by comparing the analyte:internal standard ratios from the enzyme samples to the calibration curves (Figure 2). The LOQ was 113 fmol for both analytes.

Figure 2.

Calibration curves for 8-MOP (A) and 5-MOP (B). The ratio of analytical to isotopically-labeled internal standard peak areas is plotted against the concentration of analytical standard before sample preparation. R2 values were 0.9935 and 0.9978 for 8-MOP and 5-MOP curves, respectively, as determined by 1/x - weighted linear regression. The inset in each plot visualizes the lower concentration range of each curve (same units).

2.6. Statistical analysis

SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses. The change in DIM concentration with increasing amounts of Roche H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase was evaluated with linear regression. The level of significance was α< 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Concentration of DIM in H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase and E. coli β-glucuronidase

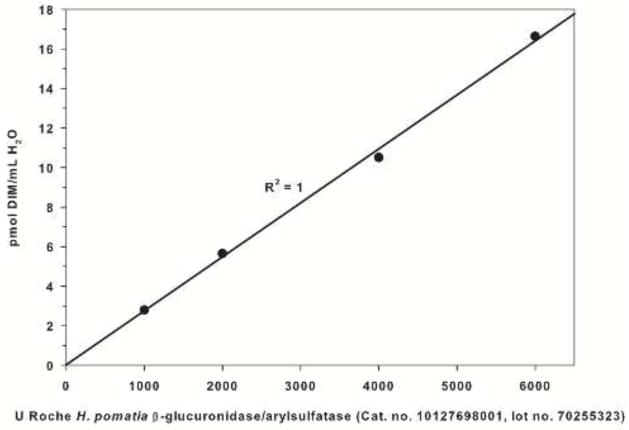

As shown in Figure 3, the treatment of H2O with increasing volumes of H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase yielded a highly significant positive linear association between quantity of enzyme and concentration of DIM (R2=1, p=0.0013). To verify that the contamination was not isolated to a single vial or lot of enzyme, additional enzymes were tested and the results are shown in Table 1. Two separate lots of β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase obtained from H. pomatia elicited mean DIM concentrations of 4.41 and 4.66 pmol/mL H2O treated, whereas H2O without any enzyme or with E. coli β-glucuronidase did not demonstrate quantifiable concentrations of DIM. Representative chromatograms of DIM detected in the enzyme formulations are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Change in DIM concentration with increasing amounts of H. pomatia β-glucuronidase (p=0.0013 for linear regression model).

Table 1.

Concentrations of DIM detected in preparations of β-glucuronidase

| β-glucuronidase preparation (2000U) | DIM pmol/mL H2O (mean ± standard error) |

|---|---|

| Nonea | <LOQ |

| Roche H. pomatia lot #70255323b | 4.41 ± 0.03 |

| Roche H. pomatia lot #70331220b | 4.66 ± 0.18 |

| Sigma E. coli G8295b | <LOQ |

Average of 5 replicates

Average of 2 replicates

LOQ = 132 fmol

Figure 4.

LC-MS analyses of DIM in Roche (from H. pomatia, panels A–B) and Sigma (from E. coli, panels C–D) β-glucuronidase preparations. The analytes are shown in panels A and C (m/z 247.12 → 130.07), and the internal standards in panels B and D (m/z 249.12 → 132.07). Note that the internal standard d2-DIM contributes 0.64% of its signal to the analyte channel.

These results demonstrate that Roche β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase from H. pomatia (cat. no. 10127698001) is contaminated with appreciable quantities of DIM. No previously published studies have quantified urinary DIM from cruciferous vegetable intake, but work in our laboratory established that consumption of low-glucobrassicin cabbage by healthy human volunteers (n=25) yielded urinary DIM concentrations well below the average values measured in H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase (manuscript under review). Recent studies have established that the same enzyme is contaminated with trace amounts of estrogen and catechin metabolites; however, the application of a contaminated enzyme may be less problematic for this research given the larger urinary concentrations of the analytes of interest relative to the amounts contributed by the contaminated enzyme, which may differ by as much as 1000-fold (Grace and Teale, 2006; Nakamura et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2005). In our present study, the similar—or even greater—concentrations of DIM from the contaminated enzyme precludes the use of corrective equations given the heterogeneous nature of urine samples. The use of β-glucuronidase expressed in E. coli (Sigma) eliminated this contamination while also increasing the yield of urinary DIM relative to no enzyme treatment (unpublished data).

3.2. Concentration of 5-MOP and 8-MOP in H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase and E. coli β-glucuronidase

Table 2 presents the results of 8-MOP and 5-MOP concentrations in several preparations of H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase and the same E. coli source of β-glucuronidase shown in Table 1. The mean concentrations of 8-MOP in crude and size-exclusion chromatography-purified preparations of H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase were 3.27 and 6.03 pmol/mL H2O treated, respectively. With regard to 5-MOP, the quantities detected in H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase were lower than 8-MOP, with an average of 0.17 pmol/mL H2O in the crude enzyme and 0.40 pmol/mL in the purified enzyme preparations. Concentrations of 8-MOP and 5-MOP below the LOQ were detected in two lots of a partially purified H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase. Representative chromatograms of 8-MOP and 5-MOP detected in the enzyme formulations are shown in Figure 5.

Table 2.

Concentrations of 8-MOP and 5-MOP detected in preparations of β-glucuronidase

| β-glucuronidase preparation (3000U)a | 8-MOP pmol/mL H2O (mean ± standard error) | 5-MOP pmol/mL H2O (mean ± standard error) |

|---|---|---|

| None | ND | ND |

| Sigma H. pomatia G7017 HP-2, crude solution | 3.27 ± 0.012 | 0.17 ± 0.012 |

| Sigma H. pomatia G0751 H-1, partially purified powder (lot 068K38091V) | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| Sigma H. pomatia G0751 H-1, partially purified powder (lot 071M7024V) | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| Sigma H. pomatia G1512 H-5, lyophilized powder | 6.03 ± 0.026 | 0.40 ± 0.022 |

| Sigma E. coli G8295 | ND | ND |

Average of 2 replicates

LOQ = 113 fmol

Figure 5.

LC-MS analyses of 8-MOP and 5-MOP in Sigma G1512 (A), G7017 (B), G0751 (C–D), and G8295 (E) β-glucuronidase preparations. Also shown is a representative internal standard chromatogram from the same analysis as panel A (Sigma G1512, F). To more intuitively reflect the degree of contamination in each enzyme preparation, each plot scales the analyte signal relative to the height of its respective 8-MOP-d3 peak. The internal standard was present at 1 nM prior to sample preparation, and in panel F the G1512 internal standard is scaled to itself. Analyte and internal standard mass transitions were m/z 217 → 90 and 220 → 90, respectively.

The data establish that Sigma β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase from H. pomatia (G7017 and G1512) is contaminated with substantial concentrations of 8-MOP and 5-MOP, thereby limiting its use in urine sample preparation for the measurement of these compounds. Previous research of 8-MOP and 5-MOP has focused on pharmaceutical treatment with psoralen for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, vitiligo, and psoriasis, resulting in peak serum concentrations of 8-MOP and 5-MOP several hundred times greater than the amounts detected in the contaminated H. pomatia enzymes (Shephard et al., 1999). However, the urinary concentrations of 8-MOP and 5-MOP from apiaceous vegetable consumption are much lower than those from pharmacological therapy, increasing the likelihood of inaccurate results and misclassification bias from the use of a contaminated enzyme. This problem is amplified by the rapid urinary elimination of dietary 8-MOP and 5-MOP (unpublished data), leaving a narrow post-ingestion window for urine collection when the excreted analytes will generate significantly more signal than the enzyme contamination. Additionally, 8-MOP and 5-MOP were most concentrated in a preparation purified by size-exclusion chromatography (Sigma-Aldrich G1512), demonstrating that this technique is insufficient to eliminate contaminants that may bind with high affinity to proteins in the preparation (Artuc et al., 1979). Although a partially purified preparation of β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase from H. pomatia (Sigma-Aldrich G0751) did not demonstrate quantifiable contamination with 8-MOP or 5-MOP, the difficulty in predicting the distribution of contamination across samples when using a snail-sourced enzyme due to the low solubility and high protein binding of 8-MOP and 5-MOP precludes its use in these highly sensitive analyses. As with DIM, an E. coli source of β-glucuronidase did not contain 8-MOP or 5-MOP.

4. Conclusions

The results demonstrate that β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase from H. pomatia is contaminated with appreciable amounts of DIM (Roche cat. no. 10127698001) as well as 8-MOP and 5-MOP (Sigma-Aldrich G7017 and G1512). In contrast, recombinant β-glucuronidase produced in E. coli does not contain significant amounts of DIM, 5-MOP, or 8-MOP; however, it should be noted that this preparation lacks sulfatase activity. Sulfatase produced by another bacterial source, A. aerogenes, may be an option if this activity is also desired (Nakamura et al., 2011). The identification of these compounds in H. pomatia enzymes adds to a burgeoning list of contaminants that includes phytoestrogens and catechins (Grace and Teale, 2006; Nakamura et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2005). This suggests additional plant bioactives may be present in preparations from H. pomatia, and underscores the risk of false positive results and misclassification of exposure status when applying this enzyme preparation to dietary biomarker methods. We recommend cautious planning for experiments that require the use of enzyme treatment and consideration of the potential exposures of enzymes to analytes of interest and other interferences. By demonstrating that enzymes from H. pomatia are contaminated with plant bioactive compounds, we hope to save investigators from the time and expense associated with contamination during method development. The value of blank samples, especially those containing neither the analytical nor the internal standards, cannot be overemphasized.

Helix pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase is contaminated with 3 phytochemicals.

H. pomatia β-glucuronidase/arylsulfatase has 4.5 pmol 3,3′-diindolylmethane/2000 U.

This enzyme has 3.5 pmol 8-methoxypsoralen and 0.2 pmol 5-methoxypsoralen/3000 U.

Enzyme purified by size exclusion chromatography has more of each phytochemical.

Recombinant β-glucuronidase from E. coli is not contaminated with these compounds.

Acknowledgments

Xun Ming, J. Bradley Hochalter, Brock Matter, Peter Villalta. This work was supported in part by P30 CA77598 from the National Institutes of Health, utilizing the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center Analytical Biochemistry shared resource. The project described was supported by Award Number T32CA132670 and by 5K07CA128952-02 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DIM

3,3′-diindolylmethane

- I3C

indole-3-carbinol

- LOQ

limit of quantitation

- 5-MOP

5-methoxypsoralen

- 8-MOP

8-methoxypsoralen

- ND

not detected

- UGT

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aggarwal BB, Ichikawa H. Molecular targets and anticancer potential of indole-3-carbinol and its derivatives. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1201–1215. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderton MJ, Manson MM, Verschoyle RD, Gescher A, Lamb JH, Farmer PB, Steward WP, Williams ML. Pharmacokinetics and tissue disposition of indole-3-carbinol and its acid condensation products after oral administration to mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5233–5241. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artuc M, Stuettgen G, Schalla W, Schaefer H, Gazith J. Reversible binding of 5- and 8-methyoxypsoralen to human serum proteins (albumin) and to epidermis in vitro. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101:669–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb05645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CD, Milner JA. Biomarkers for diet and cancer prevention: potentials and challenges. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1262–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick G, Heaney R. Glucosinolates and their breakdown products in cruciferous crops, foods and feeding stuffs. Food Chem. 1983;11:249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage N, Barnett A, Hempel N, Duggleby RG, Windmill KF, Martin JL, McManus ME. Human sulfotransferases and their role in chemical metabolism. Toxicol Sci. 2006;90:5–22. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace PB, Teale P. Purification of the crude solution from Helix pomatia for use as beta-glucuronidase and aryl sulfatase in phytoestrogen assays. J Chromatogr, B. 2006;832:158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang IS, Lee J, Lee DG. Indole-3-carbinol Generates Reactive Oxygen Species and Induces Apoptosis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:1602–1608. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AH, Prasitpan N, Shannon PV, Tinker AC. Electrophilic substitution in indoles. Part 15 The reaction between methylenedi-indoles and p-nitrobenzenediazonium fluoroborate. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1987;1:2543–2551. [Google Scholar]

- John B, Chasseaud L, Wood S, Forlot P. Metabolism of the anti-psoriatic agent 5-methyoxypsoralen in humans: Comparison with rat and dog. Xenobiotica. 1992;22:1339–1351. doi: 10.3109/00498259209053162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang AY, Young LR, Dingfelder C, Peterson S. Effects of Furanocoumarins from Apiaceous Vegetables on the Catalytic Activity of Recombinant Human Cytochrome P-450 1A2. Protein J. 2011;30:447–456. doi: 10.1007/s10930-011-9350-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HR, Jang SE, Beik WH, Lee SH, Hwang JH. Chemosensitivity of indole-3-carbinol via downregulation of microRNA-21 in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:232–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner H, Vulimiri S, Reed M, Uberecken A, DiGiovanni J. Role of cytochrome P450 1a1 and 1b1 in the metabolic activation of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and the effects of naturally occurring furanocoumarins on skin tumor formation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:226–235. doi: 10.1021/tx010151v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs L, Peter R, Thompson S, Rettie A, Trager W. Mechanism-based inactivation of human liver cytochrome P450 2A6 by 8-methoxypsoralen. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:1407–1415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe JW, King IB, Li S, Grate MT, Barale KV, Chen C, Feng ZD, Potter JD. Brassica vegetables increase and apiaceous vegetables decrease cytochrome P450 1A2 activity in humans: changes in caffeine metabolite ratios in response to controlled vegetable diets. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1157–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconett CN, Sundar SN, Tseng M, Tin AS, Tran KQ, Mahuron KM, Bjeldanes LF, Firestone GL. Indole-3-carbinol downregulation of telomerase gene expression requires the inhibition of estrogen receptor-alpha and Sp1 transcription factor interactions within the hTERT promoter and mediates the G(1) cell cycle arrest of human breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1315–1323. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer A, Nieborowski A, Strasser C, Lohr C, Schrenk D. Major furocoumarins in grapefruit juice I: Levels and urinary metabolite(s) Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:3224–3231. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Tanaka R, Ashida H. Possible evidence of contamination by catechins in deconjugation enzymes from Helix pomatia and Abalone entrails. Biosci, Biotechnol, Biochem. 2011;75:1506–1510. doi: 10.1271/bbb.110210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naritomi Y, Teramura Y, Terashita S, Kagayama A. Utility of microtiter plate assays for human cytochrome P450 inhibition studies in drug discovery: application of simple method for detecting quasi-irreversible and irreversible inhibitors. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2004;19:55–61. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.19.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine MF, Widmer WW, Hart HL, Pisek SN, Beavers KL, Criss AB, Brown SS, Thomas BF, Watkins PB. A furanocoumarin-free grapefruit juice establises furanocoumarins as the mediators of the grapefruit juice-felodipine interaction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1097–1105. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S, Lampe JW, Bammler TK, Gross-Steinmeyer K, Eaton DL. Apiaceous vegetable constituents inhibit human cytochrome P-450 1A2 (hCYP1A2) activity and hCYP1A2-mediated mutagenicity of aflatoxin B-1. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006;44:1474–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Campbell C, Robertson A, Wells A, Kleiner H. Naturally occurring coumarins inhibit 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene DNA adduct formation in mouse mammary gland. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1204–1213. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Melkamu T, Upadhyaya P, Kassie F. Indole-3-carbinol inhibited tobacco smoke carcinogen-induced lung adenocarcinoma in A/J mice when administered during the post-initiation or progression phase of lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2011;311:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed GA, Arneson DW, Putnam WC, Smith HJ, Gray JC, Sullivan DK, Mayo MS, Crowell JA, Hurwitz A. Single-dose and multiple-dose administration of indole-3-carbinol to women: pharmacokinetcs based on 3,3′-diindolylmethane. Cancer Epidemiol, Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2477–2481. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed GA, Peterson KS, Smith HJ, Gray JC, Sullivan DK, Mayo MS, Crowell JA, Hurwitz A. A phase I study of indole-3-carbinol in women: Tolerability and effects. Cancer Epidemiol, Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1935–1960. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers E, Ramamoorthy Y, Zeman M, Djordjevic M, Tyndale R. The effect of methoxsalen on nicotine and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) metabolism in vivo. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:891–899. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001615231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard SE, Zogg M, Burg G, Panizzon RG. Measurement of 5-methoxypsoralen and 8-methoxypsoralen in saliva of PUVA patients as a noninvasive, clinically relevant alternative to monitoring in blood. Arch Dermatol Res. 1999;291:491–499. doi: 10.1007/s004030050443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub RE, Onisko B, Bjeldanes LF. Fate of 3,3′-diindolylmethane in cultured MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:436–442. doi: 10.1021/tx050325z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stresser D, Williams D, Griffin D, Bailey G. Mechanisms of tumor modulation by indole-3-carbinol. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:965–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassaneeyakul W, Guo L, Fukuda K, Ohta T, Yamazoe Y. Inhibition selectivity of grapefruit juice components on human cytochromes P450. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;378:356–363. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JI, Grace PB, Bingham SA. Optimization of conditions for the enzymatic hydrolysis of phytoestrogen conjugates in urine and plasma. Anal Biochem. 2005;341:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukey RH, Strassburg CP. Human UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:581–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TTY, Schoene NW, Milner JA, Kim YS. Broccoli-derived phytochemicals indole-3-carbinol and 3,3′-diindolylmethane exerts concentration-dependent pleiotropic effects on prostate cancer cells: Comparison with other cancer preventive phytochemicals. Mol Carcinog. 2012;51:244–256. doi: 10.1002/mc.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng JR, Tsai CH, Kulp SK, Chen CS. Indole-3-carbinol as a chemopreventive and anti-cancer agent. Cancer Lett. 2008;262:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhang J, Dong WG. Indole-3-carbinol (I3C)-induced apoptosis in nasopharyngeal cancer cells through Fas/FasL and MAPK pathway. Med Oncol. 2011;28:1343–1348. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]