Abstract

Aim:

The aim was to compare the micro-shear bond strength between composite and resin-modified glass-ionomer (RMGI) by different adhesive systems.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 16 discs of RMGI with a diameter of 15 mm and a thickness of 2 mm were randomly divided into four groups (n = 4). Four cylinders of composite resin (z250) were bonded to the RMGI discs with Single Bond, Clearfil SE Bond and Clearfil S3 Bond in Groups 1-3, respectively. The fourth group was the control. Samples were tested by a mechanical testing machine with a strain rate of 0.5 mm/min. Failure mode was assessed under a stereo-microscope.

Results:

The means of micro-shear bond strength values for Groups 1-4 were 14.45, 23.49, 16.23 and 5.46 MPa, respectively. Using a bonding agent significantly increased micro-shear bond strength (P = 0.0001).

Conclusion:

Micro-shear bond strength of RMGI to composite increased significantly with the use of adhesive resin. The bond strength of RMGI to composite resin could vary depending upon the type of adhesive system used.

Keywords: Composite resins, clearfil se bond, dentin bonding agent, glass-ionomer, single bond

INTRODUCTION

Glass-ionomer cement (GIC) was introduced in the 1970s by Wilson and Kent. Initial conventional GICs had some disadvantages,[1,2] so polymerizable functional groups were added to their structure in order to improve the clinical application and physical and chemical properties of conventional GICs, which yielded resin-modified glass-ionomer cements (RMGICs).[3]

Use of glass-ionomers (GIs) as a base beneath composite restorations has been advocated as an effective method to reduce microleakage at restoration margins.[4]

In sandwich restorations the bond between GI and composite resin, is one of the main factor in retention, durability and sealing of the restoration. Studies have shown that one of the main factors involved in the failure of such restorations is caries and failure due to an improper bond between GI and composite resin.[5,6] The bond between GI and composite resin is micromechanical bond.[7] Some studies have shown that the use of resin-modified glass-ionomer (RMGI) in the sandwich technique results in a significantly higher bond strength to composite resin compared with the use of conventional GI.[8]

Despite widespread use of laminate technique in extensive proximal restorations, only very limited studies have evaluated the bond of GIs to composite resins with the use of different bonding systems during the past three decades.[7]

Use of bonding agents can improve the wettability of GI surface, resulting in an improvement of the bond between composite resin and both conventional GI and RMGIC.[9] RMGIs can also form chemical bonds with resin agents.[7]

During the past two decades, dental practitioners have become less interested in the application of acids in a separate etching step due to the introduction of new dentin bonding systems and self-etching bonding agents, which contain acidic monomers in their structure. Studies have shown that less time is required to apply self-etch systems.[8,10] The compositions and application techniques of these bonding systems have undergone great changes during the past 10 years; however, the bond between composite resin and GI by these bonding systems is still unknown.[7]

The aim of the present study was to compare the micro-shear bond strength between composite and RMGI by a self-etch adhesive system, a self-etch primer and an etch-and-rinse system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 16 GI discs were prepared in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) molds, 15 mm in diameter and 2 mm in thickness. The molds were filled with a light-cured RMGI cement (Vitrebond, 3M ESPE, USA), which was mixed according to manufacturer's instructions. The surface of the filled mold was pressed with a glass slab and light-cured with a Demi light-curing unit (LED Light Curing system, Kerr Corp, Orange, CA, USA) with the light intensity of 450 mW/cm2 for 40 s. The RMGIC discs were polished with 200, 400 and 600 grit carbide polishing papers and were randomly divided into four groups (n = 4) as follow:

Group 1: Surface of each disc was etched with 37% phosphoric acid (3M ESPE Dental Products, St. Paul, MN 55 144, USA) for 15 s and dried for 5 s using an air syringe. Subsequently, Single Bond (3M ESPE, St. Paul, USA) was applied to sample surfaces and light-cured according to manufacturer's instructions. Then, 4 cylindrical plastic molds, measuring 0.8 mm in internal diameter and 2 mm in height, were placed on the disc surface and Z250 light-cured composite resin (Z250, 3M ESPE, USA) was carefully placed inside the molds using a periodontal probe and light-cured for 40 s.

Group 2: The procedures were the same as those in Group 1 except that Clearfil SE Bond self-etch primer (Kuraray, Japan) was used according to manufacturer's instructions.

Group 3: The procedures were the same as those in Group 1 except that Clearfil S3 Bond self-etch adhesive (Kuraray, Japan) was used according to manufacturer's instruction.

Group 4: This group served as the control and no bonding agent was used between RMGIC and light-cured composite resin.

The prepared samples were stored in distilled water at room temperature for 1 h; then, the plastic cylinders were removed using a scalpel blade. They were stored in distilled water at 37 ± 2°C for 24 h.

Micro-shear bond strength test

The samples were fixed on the mechanical jaw of mechanical-universal testing machine (SANTAM, SMT-20, Iran) and a thin stainless steel wire loop (0.35 mm diameter) was positioned such that it contacted the junction between the RMGIC discs and composite bonded assembly. The load was applied at a strain rate of 0.5 mm/min until bond failure and the force applied was calculated in MPa in relation to the surface area of the resin cylinder cross-section. Data was analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey Honestly significant difference (HSD) tests and statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS software version 11.0 (IBM Corp. New Orchard Road, Armonk, New York, USA) at a significance level of P < 0.05.

Stereomicroscopic analysis

Subsequent to micro-shear bond strength test, the fractured surfaces on GI disc samples were evaluated under a stereomicroscope (SZ240, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) under a magnification of ×40 and fractures were classified as follows:

Cohesive fracture: Fracture within GI or composite resin

Adhesive fracture: Fracture at composite resin — glass-ionomer interface

Mixed fracture.

RESULTS

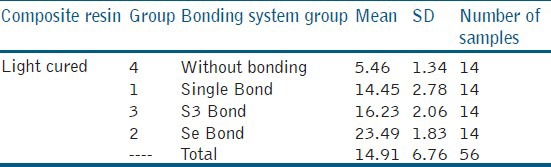

The means of micro-shear bond strength values and standard deviations are indicated in Table 1. The highest and lowest micro-shear bond strength were recorded in Group 2, Clearfil SE (23.49 ± 1.83) MPa and Group 4 (control) (5.46 ± 1.34) MPa, respectively.

Table 1.

Means and standard daviations of microshear bond strength values(MPa)in the groups under study

One-way ANOVA showed that application of a bonding agent between composite and GI significantly increase the micro-shear bond strength values (P = 0.001). In addition, the type of bonding system had a significant effect on micro-shear bond strength (P = 0.001).

Tukey HSD tests showed that application of two-step self-etch bonding system resulted in the highest bond strength to RMGI (P = 0.05).

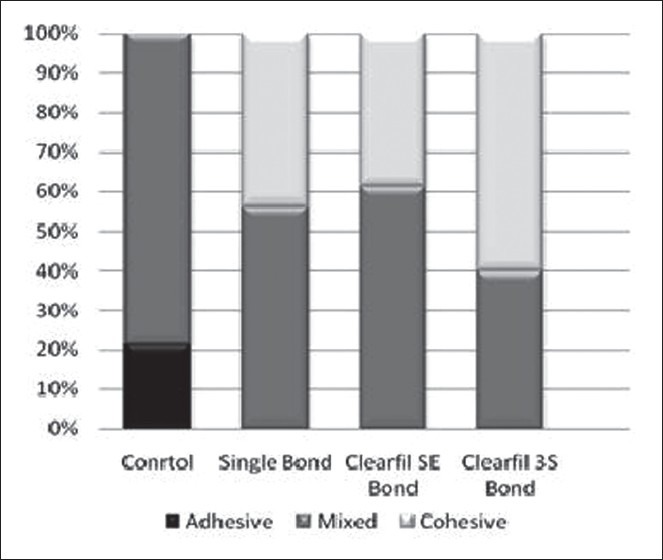

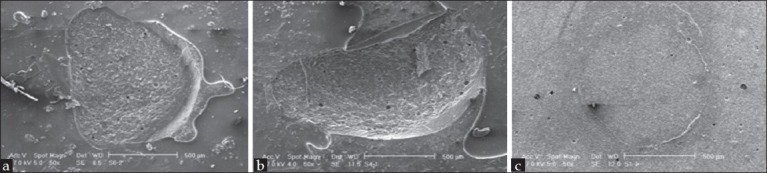

Microscopic evaluation

The fractured surfaces of all the samples were evaluated under a stereomicroscope for fracture pattern and the results are presented as frequency percentages in Figure 1 and for more accurate evaluations, the surface morphologies of some samples were evaluated under standard error of mean [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Frequency percentages of the fracture patterns of samples in the groups under study

Figure 2.

Morphological evaluation of fractured surfaces by using standard error of mean: (a) Mixed fracture, (b) cohesive fracture and (c) adhesive fracture

DISCUSSION

One of the primary goals of tooth restorations is their longevity and durability, which is especially under discussion in the gingival areas of Class II restorations. Polymerization shrinkage of composite resins in these areas might lead to the formation of gaps between the restoration and tooth structure, finally resulting in tooth hypersensitivity and pulpal damage.[11] Therefore, use of the sandwich technique has been suggested to prevent such problems.[12]

A large number of studies have shown that RMGIC has significantly higher mechanical properties and bond strength compared with conventional GI.[13] In some RMGICs light-curing reaction of the cement takes place in three stages, consisting of one acid-base reaction at the beginning, then polymerization of free radicals of methacrylate and Hydroxy ethylmethacrylate (HEMA) groups initiated by visible light and the relevant initiators and finally continuation of curing of methacrylate groups through a self-cured chemical reaction.[14]

In addition to the micromechanical bond between composite and RMGI, formation of an air-inhibited layer on the surface results in an increase in the number of unsaturated carbon double bonds, which might give rise to improved chemical bond strength to composite.[14]

The presence of resin in the structure of RMGICs prevents immediate absorption of water and in general RMGICs have superior mechanical properties, including higher cohesive strength and lower modulus of elasticity, compared with conventional GIs.[15]

Considering the above-mentioned reasons, the bond strength of RMGICs to composite was evaluated in the present study.

The results showed that application of dentin-bonding systems resulted in an increase in the bond strength between composite and RMGIC (P < 0.05); a large number of previous studies have also suggested the application of bonding agents, confirming the results of the present study.[7,16] Some previous studies have shown that the use of self-etch systems results in a higher bond strength between GI and composite resin compared with that with etch-and-rinse systems, confirming the results of the present study.[16,17]

Etching the surface of RMGIC with 37% phosphoric acid compromises the surface layer by dissolving the fillers beneath the surface layer matrix of GI cement; therefore, the cohesive strength of RMGIC decreases and as a result, tensile and shear bond strengths between composite resin and GI decrease.[17,18] However, a study by Zhang et al.[7] showed no significant differences in bond strength by decreasing the etching duration recommended by the manufacturer.

On the other hand, etching and rinsing can decrease HEMA and functional methacrylate groups on the surface of RGMI by interfering with the oxygen-inhibited layer and therefore, by eliminating the agents involved in chemical bonding decreases its bond strength to composite resin.[19] Since etch-and-rinse systems require two separate steps of rinsing and drying, they have a high technique sensitivity and might weaken GI and produce microcracks during drying of its surface. In addition, a large amount of solvents has been used in the structure of the majority of etch-and-rinse bonding systems, which might significantly decrease bond strength if they are not completely evaporated from the GI surface.[7]

Previous studies on self-etch bonding systems have shown that these systems can bond to the calcium in tooth structure;[14] therefore, it is possible that they can bond to the calcium and strontium in the GI structure and exhibit a higher bond strength compared with etch-and-rinse bonding systems.[7]

In the present study, two self-etch systems of SE Bond and S3 Bond were used to make a comparison between self-etch systems. SE Bond is a two-step self-etch primer without fluoride, which contains acidic monomers 10-Methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (10-MDP) and dissolves the surface of RMGIC to produce a mildly etched GI surface.[20] The pH of these two systems are 2 (SE Bond) and 2.7 (S3 Bond) and it is possible that SE Bond primer can result in a more effective etching of the surface compared to SE Bond due to its higher acidity, resulting in a higher bond strength. Two-by-two comparison of the groups with Tukey tests in the present study showed a higher bond strength between GI and light-cured composite resin with the use of self-etch primer system (Clearfil SE Bond) compared with other groups (P < 0.05). The lowest bond strength was recorded in the Single Bond groups among the groups, in which a bonding agent was used between GI and composite resin (P < 0.05).

One of the factors affecting bond strength is the viscosity of the bonding agent. Mount reported that higher bond strength is achieved between composite resin and RMGIC with a decrease in the viscosity of bonding agent due to the lower contact angle, resulting in better wetting of the surface by the bonding agent.[21] Comparison of the two self-etch systems in the present study showed that SE Bond had a lower viscosity compared with S3 Bond, which can explain the higher bond strength of this bonding system with light-cured composite resins.

As the results of the present study showed except for the control group, in which adhesive and mixed fractures had happened, in other groups the failures were of the cohesive and mixed types; cohesive fractures were especially noticeable in the self-etch groups. Some researchers have indicated that cohesive fracture in the substrate is a reflection of a high bond strength;[22] however, some others have reported no relationship between the bond strength and fracture type.[23] In the majority of previous studies most of the fractures of GICs and RMGICs have been of the cohesive type,[24] which might be attributed to the physical and mechanical shortcomings of the tests used in those studies. For example, stresses which are out of the center during the test, small porosities within the cement, which act as foci with the potential of generating stresses and differences in the setting reaction of GI and composite resin[6,11,20] might be factors responsible for cohesive fractures.

CONCLUSION

Under the limitations of the present study, it can be concluded that:

Application of bonding systems results in an increase in micro-shear bond strength between RMGIC and light-cured composite resins compared to that in the control group.

Application of self-etch systems resulted in a greater increase in micro-shear bond strength between RMGIC and light-cured composite resin compared with the use of etch-and-rinse systems.

The highest micro-shear bond strength between RMGIC and light-cured composite resin was achieved with the use of two-step self-etch primer system.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.McLean JW, Wilson AD. The clinical development of the glass-ionomer cement. II. Some clinical applications. Aust Dent J. 1977;22:120–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1977.tb04463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mount GJ. Buonocore Memorial Lecture. Glass-ionomer cements: Past, present and future. Oper Dent. 1994;19:82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathis RS, Ferracane JL. Properties of a glass-ionomer/resin-composite hybrid material. Dent Mater. 1989;5:355–8. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(89)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman M. Polymerization shrinkage of resin-based restorative materials. Aust Dent J. 1983;28:156–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1983.tb05272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodrigues SA, Junior, Pin LF, Machado G, Della Bona A, Demarco FF. Influence of different restorative techniques on marginal seal of class II composite restorations. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010;18:37–43. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572010000100008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loguercio AD, Alessandra R, Mazzocco KC, Dias AL, Busato AL, Singer Jda M, et al. Microleakage in class II composite resin restorations: Total bonding and open sandwich technique. J Adhes Dent. 2002;4:137–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Burrow MF, Palamara JE, Thomas CD. Bonding to glass ionomer cements using resin-based adhesives. Oper Dent. 2011;36:618–25. doi: 10.2341/10-140-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Liu Y, Liu Y, Söremark R, Sundström F. Flexure strength of resin-modified glass ionomer cements and their bond strength to dental composites. Acta Odontol Scand. 1996;54:55–8. doi: 10.3109/00016359609003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinoura K, Onose H, Moore BK, Phillips RW. Effect of the bonding agent on the bond strength between glass ionomer cement and composite resin. Quintessence Int. 1989;20:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burrow MF, Kitasako Y, Thomas CD, Tagami J. Comparison of enamel and dentin microshear bond strengths of a two-step self-etching priming system with five all-in-one systems. Oper Dent. 2008;33:456–60. doi: 10.2341/07-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tziafas D, Smith AJ, Lesot H. Designing new treatment strategies in vital pulp therapy. J Dent. 2000;28:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(99)00047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagge MS, Lindemuth JS, Mason JF, Simon JF. Effect of four intermediate layer treatments on microleakage of class II composite restorations. Gen Dent. 2001;49:489–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCabe JF. Resin-modified glass-ionomers. Biomaterials. 1998;19:521–7. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farah CS, Orton VG, Collard SM. Shear bond strength of chemical and light-cured glass ionomer cements bonded to resin composites. Aust Dent J. 1998;43:81–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1998.tb06095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanata RL, Navarro MF, Ishikiriama A, da Silva e Souza MH, Júnior, Delazari RC. Bond strength between resin composite and etched and non-etched glass ionomer. Braz Dent J. 1997;8:73–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arora V, Kundabala M, Parolia A, Thomas MS, Pai V. Comparison of the shear bond strength of RMGIC to a resin composite using different adhesive systems: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2010;13:80–3. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.66716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopikrishna V, Abarajithan M, Krithikadatta J, Kandaswamy D. Shear bond strength evaluation of resin composite bonded to GIC using three different adhesives. Oper Dent. 2009;34:467–71. doi: 10.2341/08-009-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue S, Abe Y, Yoshida Y, De Munck J, Sano H, Suzuki K, et al. Effect of conditioner on bond strength of glass-ionomer adhesive to dentin/enamel with and without smear layer interposition. Oper Dent. 2004;29:685–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heintze SD, Ruffieux C, Rousson V. Clinical performance of cervical restorations – A meta-analysis. Dent Mater. 2010;26:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuchiya S, Nikaido T, Sonoda H, Foxton RM, Tagami J. Ultrastructure of the dentin-adhesive interface after acid-base challenge. J Adhes Dent. 2004;6:183–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mount GJ. The wettability of bonding resins used in the composite resin/glass ionomer ‘sandwich technique’. Aust Dent J. 1989;34:32–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1989.tb03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanumiharja M, Burrow MF, Tyas MJ. Microtensile bond strengths of glass ionomer (polyalkenoate) cements to dentine using four conditioners. J Dent. 2000;28:361–6. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almuammar MF, Schulman A, Salama FS. Shear bond strength of six restorative materials. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2001;25:221–5. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.25.3.r8g48vn51l46421m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fahmy AE, Farrag NM. Microleakage and shear punch bond strength in class II primary molars cavities restored with low shrink silorane based versus methacrylate based composite using three different techniques. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2010;35:173–81. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.35.2.u6142007hj421041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]