Abstract

Defecation in communal latrines is a common behaviour of extant mammals widely distributed among megaherbivores. This behaviour has key social functions with important biological and ecological implications. Herbivore communal latrines are only documented among mammals and their fossil record is exceptionally restricted to the late Cenozoic. Here we report the discovery of several massive coprolite associations in the Middle-Late Triassic of the Chañares Formation, Argentina, which represent fossil communal latrines based on a high areal density, small areal extension and taphonomic attributes. Several lines of evidence (size, morphology, abundance and coprofabrics) and their association with kannemeyeriiform dicynodonts indicate that these large synapsids produced the communal latrines and had a gregarious behaviour comparable to that of extant megaherbivores. This is the first evidence of megaherbivore communal latrines in non-mammal vertebrates, indicating that this mammal-type behaviour was present in distant relatives of mammals, and predates its previous oldest record by 220 Mya.

Communal latrines or defecation spots are places where multiple individuals defecate repeatedly producing dungheaps1. This behaviour has been reported in some groups of extant mammals, including carnivores2,3,4, primates2,5,6, rodents7 and marsupials8. In particular, this behaviour is particularly frequent in large herbivorous mammals (> 100 kg), such as equids9,10, tapirs11, antelopes10,12, rhinoceros13, elephants14, and South American camelids15. Defecation in communal latrines has important biological and ecological implications for the producer-species2, being related with intra- and inter-specific communication3,4, reproduction8,16, defence against predators3,16, and prevention of intestinal parasite re-infestation9. Communal latrines have also a key role in extant ecosystems with direct impact on plant populations and vegetation dynamics2,6,17. As a result, coprolite (fossil faeces) accumulations can provide potentially unique information about the ecology of ancient ecosystems. Although there are reports of thousands of coprolites from herbivorous and carnivorous amniotes18,19,20,21, latrines are extremely rare in the fossil record22, being restricted to the late Cenozoic and unknown among extinct and extant non-mammal megaherbivore vertebrates (>1,000 kg animals23,24).

Here we report the first non-mammal megaherbivore communal latrines from eight massive coprolite accumulations in the Middle-Late Triassic (ca. 235 Mya) of the Chañares Formation (La Rioja Province) of northwestern Argentina (Fig. 1). The defecation spots are situated in the El Torcido locality and surrounding areas and each latrine is composed of hundreds to thousands of in situ coprolites assigned to megaherbivore dicynodonts. We describe here the geological and sedimentological characteristics of the communal latrine-bearing areas, the general features of the latrines and coprolites, and food habits and social behaviour of the producer-species. Defecation of dicynodonts in communal latrines reveals that this gregarious behaviour is not unique to mammals and predates its previous oldest record in around 220 million years.

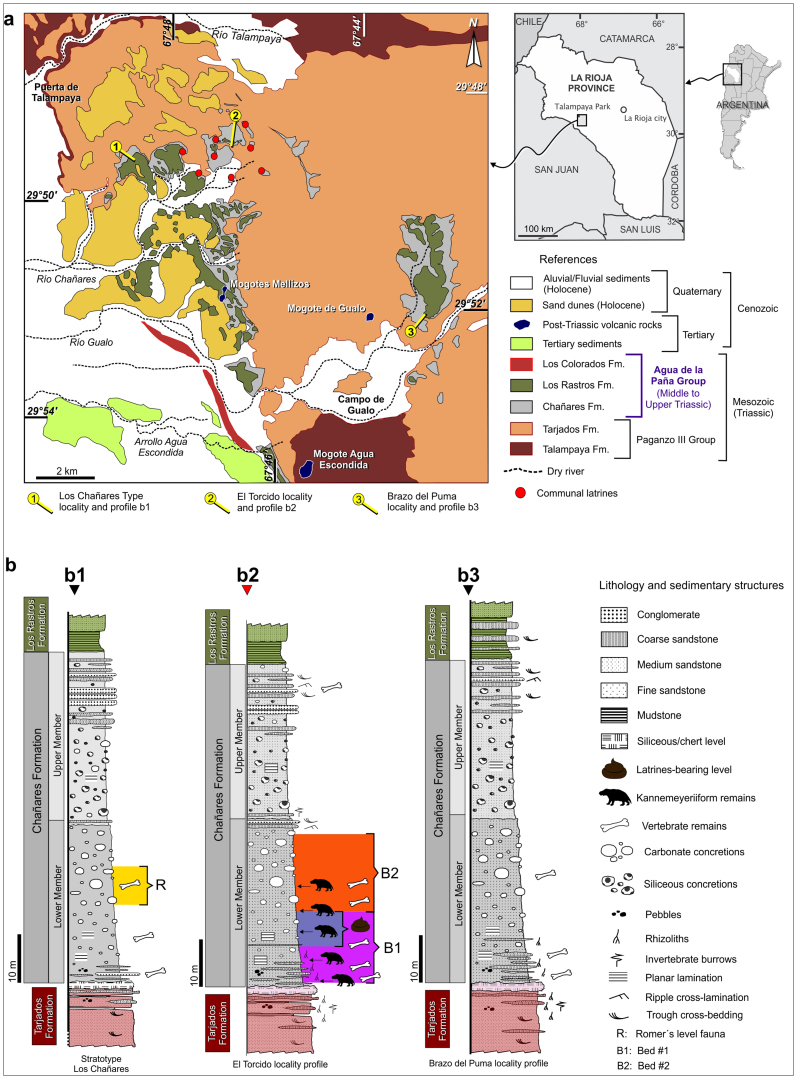

Figure 1. Geographical and geological setting.

(a) Location and geological maps of the studied area, Los Chañares, La Rioja Province, Argentina. 1,2 and 3, indicate the occurrence of the communal latrines and the stratigraphic profiles of b. (b) Stratigraphic profiles of the Chañares Formation in Los Chañares (b1), El Torcido (b2) and Brazo del Puma (b3) localities, showing the level where communal latrines were found (b2, Lower Member, Bed 1). Maps drawn in Corel Draw Graphics Suite ×5 based on Google Earth images and personal field observations.

Results

Geological setting

The Ladinian–earliest Carnian25,26 Chañares Formation crops out in southwestern La Rioja Province, NW Argentina (Fig. 1a), as part of the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin (see Supplementary Figure 1). This basin represents a Triassic continental succession of around 4,000 metres of alluvial, fluvial, and lacustrine sediments. The Chañares Formation is one of the most fossiliferous Middle-Late Triassic continental tetrapod-bearing assemblages worldwide27 (see Supplementary Information). Its best-sampled locality is “Los Chañares”25, which historically yielded hundreds of fairly complete and articulated tetrapod specimens27 (Fig. 1 and Supp. Fig. 1).

The Chañares Formation was deposited in an alluvial to fluvial-lacustrine environment within an active rift basin that received sediments from surrounding highlands, as well as copious amounts of volcanic ash27,28. Following previous suggestions that the Chañares Formation comprises two clearly distinct lithological units25,27 (Fig. 1b), the formation is divided here into a lower and an upper member (see Supplementary Information). The lower member reaches up to 35 metres of thickness and represents the lower lithological unit that bears the volcanogenic concretions that characterize the formation and historically yielded the vast majority of vertebrate fossil remains27. Two beds with clear distinguishable lithology are recognized within this member (see Supplementary Information). The communal latrines are situated in the upper section of the lower bed, between 8 to 15 metres from the base of the stratigraphic unit (Suppl. Figs. 1 and 2). The upper member represents 30 metres of very massive and concretioned light-gray sediments bearing mostly siliceous concretions and some massive horizontal coarse sandstone beds at the uppermost levels27 (see Supplementary Information).

The Chañares Formation was traditionally considered Ladinian (late Middle Triassic) in age25,27, but more recent authors considered a Late Ladinian-earliest Carnian age based on vertebrate biostratigraphy and maximum age constrain from radioisotopic datings from overlaying formations26 (see Supplementary Information). However, the communal latrines occur in the lower levels of the Chañares Formation and, therefore, are probably in the Ladinian-Carnian boundary (Suppl. Fig. 1b).

Triassic communal latrines

A fossil communal latrine is defined here as a massive, relatively small (i.e. smaller than the expected home range of the producer herd or population) coprolite-bearing fossil field with evidence of defecation of multiple individuals.

The coprolites were found in the lower member of the Chañares Formation (Fig. 2) and they represent massive autochthonous biogenic accumulations buried in a short-term deposition event (see Supplementary Information). The latter indicates that the high coprolite densities are not taphonomical artefacts or caused by allochthonous accumulations after reworking. The areal density of coprolites is extremely high, averaging 66.6 coprolites/square metre but reaching maximum densities of 94 coprolites/square metre and an estimate of ~30,000 coprolites in the most abundant areas (see Statistics in the Supplementary Information). The autochthony is supported by the nature of the sediments (e.g., matrix supported packing), the bounded and localized coprolites accumulations, the monotypic taxonomic composition and the clump type geometric accumulation of each latrine, as well as their “intrinsic” concentrations, the pristine coprolite surfaces and the low proportion of broken coprolites (see Supplementary Information). As a result, multiple individuals should have generated these massive biogenetic depositions. Although coprolites vary in size and shape in each area, there is no substantial morphological variation among different latrines (Fig. 2c). The coprolite fields have variable areal extensions between 400 to 900 square metres and are separated around 1.5 kilometres from each other, but the latter would be biased by taphonomical artefacts and irregularity of the outcrops. However, the massive27 (see Supplementary Information) condition of the coprolite-bearing sediments prevents inferring synchronicity between these eight coprolite fields (Suppl. Fig. 1a). Coprolite accumulations are frequently associated with juvenile to adult, partially articulated dicynodonts. The areal extension of the coprolite fields is substantially smaller than the inferred distribution of the dicynodont herds (composed of adult animals with a body mass that exceeded 3,000 kg) expected for the Chañares Formation. As an outcome, the massive coprolite deposits should have not been simply the result of gregarism, but of a more complex behaviour of defecation in a punctual relatively small area. Accordingly, the coprolite accumulations of the Chañares Formation are interpreted as fossil communal latrines based on the three lines of evidence outlined above, namely their high density, relatively small areal size, and autochthonous condition.

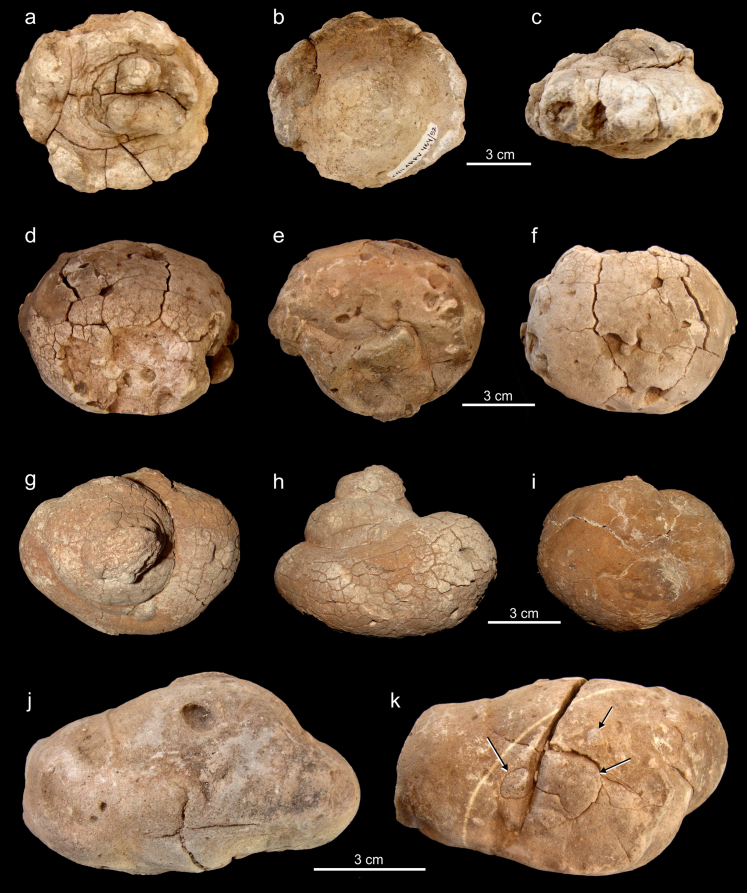

Figure 2. Coprolites from Chañares Formation.

(a) In-situ not concretioned coprolites exposed at latrine #1 (see Supplementary Information). (b) Coprolite within concretion at latrine #2. (c) Diversity of coprolite shapes and sizes from several communal latrines (CRILAR-Pv 464).

Coprolites

Coprolites collected in the Chañares Formation were found inside and outside concretions (Fig. 2a, b; Suppl. Figs. 5 and 6), but the latter condition is the most common in denser latrines (i.e., ~30,000 coprolites). These coprolites vary from whitish grey to dark grey and 0.5 to 35 cm in diameter (Fig. 2c and Suppl. Figs. 7c and 8). By contrast, coprolites preserved within volcanogenic concretions were mostly observed in low-density latrines. They show little variation in size and shape, and are dark brown-violet, resembling the colour of the concretions (Fig. 2b and Suppl. Figs. 6). Coprolite morphology is variable, but all have pristine surfaces, clear-cut edges and most of them are ovoid to spheroidal in shape, ranging from 0.5 to 10 cm in diameter. Less abundant coprolites are sausage-like with segmented surfaces, wrapped and oblate, with ragged edges, ranging from 10 to 25 cm in diameter (Fig. 2; see Suppl. Fig. 8). Coprolites with a loop/spiral, coiled or sausage-like shape (Fig. 3g–i), but lumpy and/or with cracks are less abundant. Very large coprolites (i.e., 20–35 cm in diameter; Fig. 3a–c and Suppl. Figs. 7c) are scarce and have generally a cow-dung-shape (flat round piles) with a rough surface. Upper and lower surfaces are discerned in several coprolites (see Fig. 3), in which the upper surface is rough and with deep grooves and desiccation cracks, mostly produced by weathering before burial. Conversely, the lower surface is smooth and possesses small holes produced by tiny stones and detritus on the soil surface that contacted the dung immediately after defecation (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Coprolite external features and taphonomical attributes.

(a–c) Coprolite in dorsal (a), ventral (b), and side (c) views showing desiccation grooves only on the dorsal surface. (d–f) Coprolite in dorsal (d), ventral (e), and side (f) views showing grooves and some pits generated by desiccation and soil detritus on the ventral surface. (g–i) Coprolite in dorsal (g), ventral (h), and side (i) views showing ventral smooth surface, but with very cracked –by desiccation– dorsal and side surfaces. (j–k) Coprolite in dorsal (j) and ventral (k) views showing smooth surfaces, but with lithoclasts on the ventral surface –black arrows in (k)–.

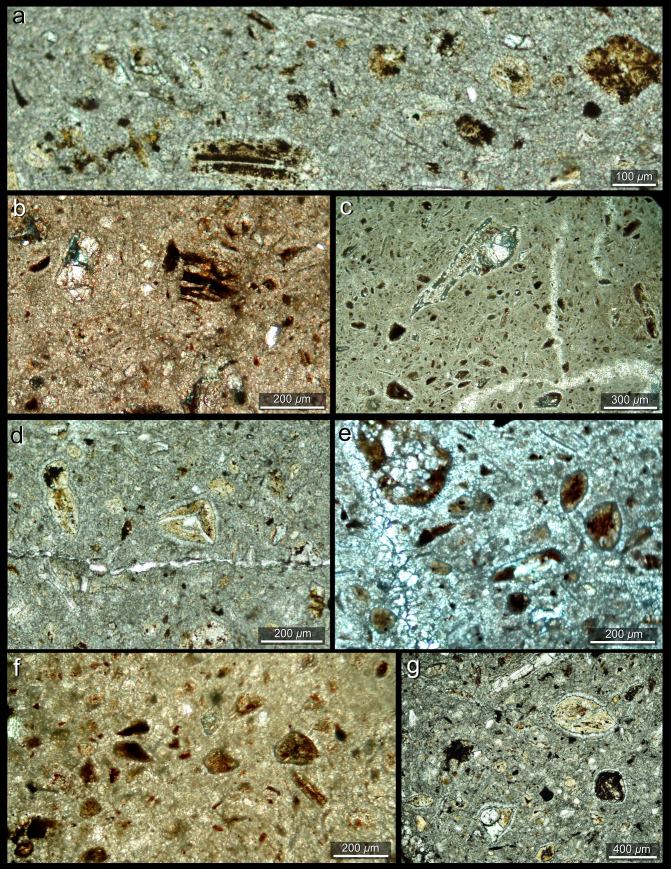

Most of the thin sections (Fig. 4) of the sampled coprolites have considerable diagenetic alteration represented by calcite (microspary) replacement. CT scans (see Suppl. Fig. 10) revealed that the coprolites are massive, but have some internal desiccation microfractures infilled by a diagenetic drusy equigranular cement (Fig. 4c and Suppl. Fig. 9g). Some coprolites possess internal microvesicles that are interpreted as gas microbubbles traces. All sampled coprolites lack internal micro-bone remains and, conversely, the coprofabrics bear abundant carbonaceous organic debris, microscopic woody plant remains and micro- and megaspores, as well as possible freshwater ostracods (Fig. 4 and Suppl. Fig. 11).

Figure 4. Coprolite thin sections from the Chañares Formation (CRILAR-c 144).

(a and b) Woody fragments in the micritic coprofabric of the specimens from Chañares latrines. (c) Leaf fragments and other woody micro-remains in the coprofabric. (d–g) Fossil mosses and ferns-like spores (microspores and megaspores) commonly observed in the coprofabric.

Discussion

Direct evidence of palaeodiets and feeding behaviour in extinct animals comes primarily from two sources of information, namely in situ gut contents and coprolites18,19,21,29,30,31. Coprolites provide unique trophic information of ancient ecosystems19 and can preserve a wide range of biogenic components, including microorganisms to vertebrate tissues32. The high abundance of coprolites in the latrines of the Chañares Formation (up to 90 coprolites/square metre; see Supplementary Information) indicates that these coprolite fields are result of defecation of multiple individuals in a single and specific area. The variation in size and morphology present in the coprolites does not differ between each sampled latrine, suggesting that they belong to a single producer. Monospecific latrines are frequent in extant large herbivorous mammals7,10,23 that show alterations in their feces due to diet variation in different age classes and seasonal changes. Thus, the size and morphological variation inside each fossil latrine may be caused by dietary changes among different age classes and/or changes in the vegetation through different seasons. The taphonomy, autochthony and the consistent internal coprofabric microstructure are lines of evidence supporting the monospecificity of the producer.

Thin sections showed abundant, well-preserved plant microfragments and CT scans showed no bone remains, indicating that the coprolites were produced by herbivorous species (see Supplementary Information and Suppl. Fig. 11). As a result, carnivorous “rauisuchians” and other carnivorous taxa known from the Chañares Formation25,27,33 are excluded as potential coprolite producers (see Supplementary Information). Moreover, cynodonts and other less numerically abundant taxa (e.g. Gracilisuchus) are discarded as potential producers because of their small body size (e.g. maximum skull length of Massetognathus 20.4 cm34). The extremely high density, size, recurrent coprofabric and internal content of the coprolites indicate that the producer-taxon was an extremely abundant herbivorous species with a large adult body size. All these lines of evidence indicate that kannemeyeriiform dicynodonts were the latrine producers and the association of each latrine with kannemeyeriiform remains strongly bolsters this hypothesis (see Supplementary Information). The dicynodont Dinodontosaurus is by far the most abundant taxon in the lowermost levels of the Chañares Formation and is represented by juvenile, sub-adult and adult individuals. Adult Dinodontosaurus specimens should have achieved a body mass that exceeded fairly 1,000 kg (probably up to 3,000 kg) and can be included confidently within the category of megaherbivore23,24 (see Supplementary Information). Accordingly, the massive coprolite accumulations of the Chañares Formation can be identified as fossil megaherbivore communal latrines.

Dicynodonts are extinct basal synapsids that were taxonomically diverse, cosmopolitan and numerically dominant in several Permian and Triassic terrestrial assemblages35,36. Several authors suggested that dicynodonts were herbivorous35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 and one of the main primary consumers among Permo-Triassic tetrapods36. They are characterized by a specialized feeding apparatus that allowed specific jaw movements for vegetation processing40,42. However, some authors disagreed with this hypothesis and alternatively suggested that at least some taxa would have been omnivorous or even carnivorous43,44. Until now, the inference of feeding habits in dicynodonts was restricted to cranial and dental features38, but direct evidence of dicynodont feeding habits remained unknown. The dicynodont latrines and coprolites described here bolster the hypothesis that the Middle-Late Triassic herbivorous kannemeyeriiforms from the Chañares Formation were the main primary consumers of their ecosystem36 and roughage-feeding megaherbivores. The characteristics observed in the dicynodont latrines closely resemble those present in communal latrines of extant herbivorous megafauna10,15,23,45. In modern ecosystems, individuals of different ages produce faeces of different sizes7,45,46. Accordingly, the occurrence of different sizes and morphologies in the coprolites of the Chañares fossil latrines suggests that they belonged to dicynodonts of different age groups30,46 (see Supplementary Information), indicating a complex behaviour of defecation in communal latrines comparable to that of some extant megaherbivores (see Supplementary Information). Moreover, this evidence bolsters the hypothesis that dicynodonts were gregarious animals, which was based previously on fossil footprints47.

Latrines and defecation spots are extremely rare in the fossil record and only some exceptionally rich accumulations of hyaena coprolites were reported22,48. Despite of reports of thousands of coprolites from herbivorous and carnivorous amniotes18,19,20,21, only a few fossil communal latrines are known from Pleistocene and Holocene mammals49. Cynodont burrows from the Early Triassic of the Karoo Basin (South Africa) that possess some terminal chambers filled with coprolites50 that may also represent communal latrines. However, reliable evidence for fossil communal latrines was unknown among non-mammal megaherbivore vertebrates. Accordingly, the massive coprolite accumulations from the Chañares Formation (Ladinian-Carnian) are the first record of communal latrines for extant and extinct non-mammal megaherbivores, indicating that this mammal-type behaviour was actually present in much older relatives of mammals, and predate its oldest fossil record in around 220 million years.

Methods

Institutional abbreviations and collected samplings

CRILAR-Pv: Centro Regional de Investigaciones Científicas y Transferencia Tecnológica La Rioja, La Rioja Province, Argentina, Paleontología de Vertebrados. 61 complete coprolites (CRILAR-Pv 464–1/61) from four fossil latrines of the Chañares Formation were collected and used for this study. 369 coprolites were measured in the field for statistical analysis. 11 coprolite thin sections were made (CRILAR-c 144–1/11). CRILAR-c 135 to 140, thin section rock samplings. Coprolite samples from four different communal latrines were collected for palaeontological, petrological, and CT analyses. Rock samples were collected from different outcrops, levels and fossil latrines of the Chañares Formation for sedimentological and microfabric analyses.

Repository

All the coprolites, rock samples and thin-slices are housed at the Colección de Paleovertebrados (Pv) del Centro Regional de Investigaciones Científicas y Transferencia Tecnológica La Rioja (CRILAR), La Rioja Province, Argentina.

Petrographic thin sections techniques

Coprolite and rock thin sections were made at the CRILAR Petrographic Laboratory using the following protocol: specimens were washed with distilled water and cut with PetroThin, dried at 40°C in an oven during 24 hours, and subsequently glued with compound glue (Araldit CY 248 and hardening HY 956) on glass slides of 28 × 48 × 1.8 mm. All thin sections are housed in the palaeontological and geological collection of the CRILAR. Thin sections analyses were made with a stereoscopic microscope (Leica MZ12) and Leica DM LB light and petrographic DM2500P microscopes. Images were captured with a Leica DFC295 digital camera attached to the microscope and connected to a computer for data processing, editing and measurement collection.

Statistics

The software environment R for statistical analysis was used to plot distribution histograms and fitt theoretical distribution using the package fitdistrplus version 1.0–1.

Computed tomography

Tomographies of seven coprolites were conducted on an axial CT scan multi slicer of 64-channel in the Clínica de la Sagrada Familia (Buenos Aires, Argentina). We obtained 515 DICOM slices with a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels, using a cutting width of 0.8 mm and 0.4 mm of progress, Field of View 421.0 mm and penetration power of 120 Kv–279 mA. The open source software 3D Slicer v4.1.1 was used for the analysis and 3D reconstruction.

Studied locality

The communal latrines are located in the El Torcido locality of the Chañares Formation, Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin, Talampaya National Park, La Rioja Province, Argentina. The El Torcido locality (29°49′S, 67°47′W) is situated about 4 km east of the “Chañares type” locality. The fossil record of the El Torcido locality is dominated by dicynodonts and considerably less abundant cynodonts, which represent together around 60–70% of all the collected tetrapods (see Supplementary Information).

Author Contributions

J.B.D. and L.E.F. planned the projects and field trips to the Talampaya National Park (2011–2012). L.E.F., E.A., J.R.A.T. and E.M.H. found different communal fossil latrines. L.E.F., M.D.E. and J.B.D. planned and designed the study and research. L.E.F., E.A. and J.R.A.T. collected morphological data. L.E.F. and E.M.H. performed thin sections at the CRILAR. J.R.A.T. and J.B.D. conducted CT scans analysis. M.D.E. and L.E.F. performed the statistical analysis. M.B.V.B. and M.J.T. collected coprolite and body fossil specimens and took pictures of the latrines. Research was conducted by L.E.F., M.D.E., E.M.H., J.B.D., E.A., J.R.A.T., M.B.V.B. and M.J.T. L.E.F., M.D.E. and E.M.H. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the final results and commented on the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Statistics data set

CT scan 1

CT scan 2

Acknowledgments

We thank the Secretaría de Cultura de La Rioja and the Administración de Parques Nacionales (APN) for granting permits to work in the Talampaya National Park. We are also indebted to the rangers of the Talampaya National Park for their help in the field and discussion with José F. Bonaparte about the Chañares Formation. We thank the following technicians that helped during data collection: Maximiliano Iberlucea (MACN-CONICET), Sergio de la Vega (CRILAR-CONICET), and Tonino Bustamante (CRILAR). We thank also P. Alasino, M. Larrovere, I. Amelotti, S. Dutto, V. Quiroga, R. Palacios, R. Butler, and S. Brusatte for comments and discussions. M.D.E. is supported by a grant of the DFG Emmy Noether Programme to Richard Butler (BU 2587/3-1). Research funded by the Agencia Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (PICT 2010-0207 to J.B.D.), The Jurassic Foundation (to M.D.E.), and Secretaría de Gobierno, La Rioja (to L.E.F.).

References

- Ralls K. & Smith D. K. Latrine use by San Joaquin kit foxes (Vulpes macrotis mutica) and coyotes (Canis latrans). West N. Am. Naturalist 64, 544–547 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- González-Zamora A. et al. Sleeping sites and latrines of spider monkeys in continuous and fragmented rainforests: implications for seed dispersal and forest regeneration. PloS ONE 7, e46852 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan N. R., Cherry M. I. & Manser M. B. Latrine distribution and patterns of use by wild meerkats: implications for territory and mate defence. Anim. Behav. 73, 613–622 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Gorman M. L. & Trowbridge B. J. in Carnivore behavior, ecology, and evolution, Vol. 1 (ed Gittleman J. L.) 57–88 (Cornell University Press, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M. T., Samonds K. E., Raharison J.-L. & Wright P. C. Lemur latrines: Observations of latrine behavior in wild primates and possible ecological significance. J. Mammal. 85, 420–427 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Russo S. E., Portnoy S. & Augspurger C. K. Incorporating animal behavior into seed dispersal models: Implications for seed shadows. Ecology 87, 3160–3174 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chame M. Terrestrial mammal feces: a morphometric summary and description. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 98, 71–94 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruibal M., Peakall R. & Claridge A. Socio-seasonal changes in scent-marking habits in the carnivorous marsupial Dasyurus maculatus at communal latrines. Aust. J. Zool. 58, 317 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Lamoot I. et al. Eliminative behaviour of free-ranging horses: do they show latrine behaviour or do they defecate where they graze? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 86, 105–121 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Stuart C. & Stuart T. A Field Guide to the Tracks and Signs of Southern and East African Wildlife (Southern Book Pub of South Africa, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Moore P. D. Ecology: palms in motion. Nature 426, 26–7 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wronski T. & Plath M. Characterization of the spatial distribution of latrines in reintroduced mountain gazelles: do latrines demarcate female group home ranges? J. Zool. 280, 92–101 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Laurie A. Behavioural ecology of the Greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis). J. Zool. 196, 307–341 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Arceiz A. & Blake S. Megagardeners of the forest – the role of elephants in seed dispersal. Acta Oecol. 37, 542–553 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Aba M. A., Bianchi C. & Cavilla V. in Behavior of Exotic Pets (ed Tynes V.) 157–167 (Wiley-Blackwell. 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Barja I., Silván G., Martínez-Fernández L. & Illera J. Physiological stress responses, fecal marking behavior, and reproduction in wild european pine martens (Martes martes). J. Chem. Ecol. 37, 253–259 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp E. W., Milleron T. & Russo S. E. in Seed Dispersal and Frugivory: Ecology, Evolution and Conservation (eds Levely D. J., Silva W. R. & Galetti M.) 19–34 (CAB International, Wallingford, UK, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Chin K. The paleobiological implications of herbivorous dinosaur coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana: why eat wood? Palaios 22, 554–566 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Chin K., Tokaryk T. T., Erickson G. M. & Calk L. C. A king-sized theropod coprolite. Nature 393, 680–682 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Prasad V. et al. Late Cretaceous origin of the rice tribe provides evidence for early diversification in Poaceae. Nat. Commun. 2, 480 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin K. in Predation in the Fossil Record (eds Kowalewski M. & Kelley P. H.) 43–49 (Paleontological Society Special Paper, 8 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Pesquero M. D. et al. An exceptionally rich hyaena coprolites concentration in the Late Miocene mammal fossil site of La Roma 2 (Teruel, Spain): Taphonomical and palaeoenvironmental inferences. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 311, 30–37 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith R. N. Megaherbivores: The Influence of Very Large Body Size on Ecology (Cambridge University Press, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Fariña R. A., Vizcaíno S. F. & De Iuliis G. Megafauna. Giant Beasts of Pleistocene South America (Indiana University Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Romer A. S. & Jensen J. The Chañares (Argentina) Triassic reptil fauna. II: Sketch of the geology of the Río Chañares-Gualo region. Breviora 252, 1–20 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- Desojo J. B., Ezcurra M. D. M. D. & Schultz C. L. An unusual new archosauriform from the Middle-Late Triassic of southern Brazil and the monophyly of Doswelliidae. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 161, 839–871 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R. R. et al. Paleoenvironment and taphonomy of the Chañares Formation tetrapod assemblage (Middle Triassic), northwestern Argentina: spectacular preservation in volcanogenic concretions. Palaios 16, 461–481 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso A. C. & Caselli A. T. Paleolimnology evolution in rift basins: the Ischigualasto–Villa Unión Basin (Central-Western Argentina) during the Triassic. Sediment. Geol. 275–276, 38–54 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M. E., Lindgren J., Chin K. & Månsby U. Coprolite morphotypes from the Upper Cretaceous of Sweden: novel views on an ancient ecosystem and implications for coprolite taphonomy. Lethaia 44, 455–468 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P. et al. Dinosaur coprolites from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Lameta Formation of India: isotopic and other markers suggesting a C3plant diet. Cretaceous Res. 24, 743–750 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Tweet J. S., Chin K., Braman D. R. & Murphy N. L. Probable gut contents within a specimen of Brachylophosaurus canadensis (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana. Palaios 23, 624–635 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Farlow J. O., Chin K., Argast A. & Poppy S. Coprolites from the Pipe Creek Sinkhole (Late Neogene, Grant County, Indiana, U.S.A.). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 30, 959–969 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt S. J. et al. in Anatomy, Phylogeny and Palaeobiology of Early Archosaurs and their Kin (eds Nesbitt S. J., Desojo J. B. & Irmis R. B.) 379 (Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Abdala F. & Giannini N. P. Gomphodont cynodonts of the Chañares Formation: the analysis of an ontogenetic sequence. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 20(3), 501–506 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Botha-Brink J. & Angielczyk K. D. Do extraordinarily high growth rates in Permo-Triassic dicynodonts (Therapsida, Anomodontia) explain their success before and after the end-Permian extinction? Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 160, 341–365 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fröbisch J. Composition and similarity of global anomodont-bearing tetrapod faunas. Earth-Sci. Rev. 95, 119–157 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- King G. M., Oelofsen B. W. & Rubidge B. S. The evolution of the dicynodont feeding system. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 96, 185–211 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Cox B. The jaw function and adaptive radiation of the dicynodont mammal-like reptiles of the Karoo basin of South Africa. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 122, 349–384 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C., Reisz R. R. & Smith R. M. H. The Permian mammal-like herbivore Diictodon, the oldest known example of sexually dimorphic armament. Proc. R. Soc. B. 270, 173–8 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinoski S. C., Rayfield E. J. & Chinsamy A. Functional implications of dicynodont cranial suture morphology. J. Morphol. 271, 705–28 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinoski S. C., Rayfield E. J. & Chinsamy A. Comparative feeding biomechanics of Lystrosaurus and the generalized dicynodont Oudenodon. Anat. Rec. 292, 862–74 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surkov M. V. & Benton M. J. Head kinematics and feeding adaptations of the Permian and Triassic dicynodonts. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 28, 1120–1129 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Sues H.-D. & Reisz R. R. Origins and early evolution of herbivory in tetrapods. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 141–145 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisz R. R. & Sues H.-D. in Evolution of Herbivory in Terrestrial Vertebrates (ed Sues H.-D.) 9–41 (Cambridge University Press, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Kohn M. H. & Wayne R. K. Facts from feces revisited. Trends Ecol. Evol. 12, 223–227 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollocher T. C., Chin K., Hollocher K. T. & Kruge M. A. Bacterial residues in coprolite of herbivorous dinosaurs: role of bacteria in mineralization of feces. Palaios 16, 547–565 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano C. A., Mancuso A. C., Palma R. M. & Krapovickas V. Tetrapod tracks in a marginal lacustrine setting (Middle Triassic, Argentina): Taphonomy and significance. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 291, 388–399 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Berger L. R. et al. A Mid-Pleistocene in situ fossil brown hyaena (Parahyaena brunnea) latrine from Gladysvale Cave, South Africa. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 279, 131–136 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Scott L., Marais E. & Brook G. A. Fossil hyrax dung and evidence of Late Pleistocene and Holocene vegetation types in the Namib Desert. J. Quaternary Sci. 19, 829–832 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald G. H., Welman J. & MacEachern J. A. Vertebrate burrow complexes from the Early Triassic Cynognathus Zone (Driekoppen Formation, Beaufort Group) of the Karoo Basin, South Africa. Palaios 16, 148–160 (2001). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

Statistics data set

CT scan 1

CT scan 2