Abstract

Objective

Despite clinical advances, surgical site infections (SSIs) remain a problem. The development of SSIs involves a complex interplay between the cellular and molecular mechanisms of wound healing and contaminating bacteria, and here, we utilize an agent-based model (ABM) to investigate the role of bacterial virulence potential in the pathogenesis of SSI.

Approach

The Muscle Wound ABM (MWABM) incorporates muscle cells, neutrophils, macrophages, myoblasts, abstracted blood vessels, and avirulent/virulent bacteria to simulate the pathogenesis of SSIs. Simulated bacteria with virulence potential can mutate to possess resistance to reactive oxygen species and increased invasiveness. Simulated experiments (t=7 days) involved parameter sweeps of initial wound size to identify transition zones between healed and nonhealed wounds/SSIs, and to evaluate the effect of avirulent/virulent bacteria.

Results

The MWABM reproduced the dynamics of normal successful healing, including a transition zone in initial wound size beyond which healing was significantly impaired. Parameter sweeps with avirulent bacteria demonstrated that smaller wound sizes were associated with healing failure. This effect was even more pronounced with the addition of virulence potential to the contaminating bacteria.

Innovation

The MWABM integrates the myriad factors involved in the healing of a normal wound and the pathogenesis of SSIs. This type of model can serve as a useful framework into which more detailed mechanistic knowledge can be embedded.

Conclusion

Future work will involve more comprehensive representation of host factors, and especially the ability of those host factors to activate virulence potential in the microbes involved.

Gary An, MD

Introduction

Despite clinical improvements in peri-operative antisepsis, antibiotics and surgical technique, and significant advances in the understanding of the molecular and cellular biology of wound healing and the impairment thereof, surgical site infections (SSIs) remain a significant clinical problem. Occurring in between 2% and 5% of all patients undergoing surgery, SSIs are the second most common type of healthcare-associated infections,1 with ∼300,000–500,000 SSI cases occurring every year in the United States.2 Though they may be related to superficial wounds, most SSIs are associated with more extensive procedures with incisions that extend to the deeper tissues such as the muscular layers.3 The most commonly isolated bacterial species are Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Enterococcus species, and Escherichia coli.4

The pathogenesis of SSIs can be generally characterized in the following manner: Tissue trauma at the site of the surgical incision, perhaps in the face of some compromise in host capabilities such as poor blood supply or immunosuppression, with concurrent inoculation beyond some threshold of bacterial contamination, leads to sufficient bacterial growth such that successful healing is impaired and the bacteria cannot be cleared, leading to an abscess.1 Also present in the current conceptual model of the pathogenesis of SSIs is the invocation of excessive inflammation, leading to a disorder of the healing processes and manifesting in the formation of an abscess. While it is clear that the immune state of the host plays a significant role in surgical wound healing, the specific shortcomings of the host defense that transition a healing wound to an infected one remain elusive.5 Therefore, since the role of host factors in the pathogenesis of SSI has received extensive research attention, we propose a complementary line of investigation with a focus on characterizing the concurrent contribution of microbes in the development of an SSI with the following assumptions and rationale:

1. We presuppose that there is some relationship between the degree of bacterial contamination and the likelihood of developing a SSI, despite the baseline host characteristics. This assumption is plausible, because there is no single group of patients that either never or always develops an SSI, and it is reasonable to state that greater contamination leads to a higher chance of SSI.

2. We assume that the threshold effect of bacterial contamination is not only a function of quantity but also of quality, that is, specific characteristics of the type of bacteria present. Not only are certain species of bacteria known to be more aggressive in terms of the development of SSIs; but also many bacterial species, such as S. aureus and Enterobacteria species, among the most common bacteria seen is SSIs, have the potential to manifest a dynamically increasing range of virulence.

3. The manifestation of bacterial virulence is a highly dynamic process, both in terms of individual microbes (i.e., through gene regulation as seen in quorum sensing) and in terms of population effects (i.e., through mutations or horizontal gene transfer and selection). This implies that the actual functional effect of a particular degree of contamination cannot be defined based on a single sample or snapshot in time, but rather can arise and progress dynamically over time. Therefore, characterizing bacterial virulence as related to the pathogenesis of SSI requires the means to capture these dynamics.

4. The “risk threshold” for the development of an SSI is a dynamic triangulation between the host state, the quantity of bacterial contamination, and the quality in terms of virulence potential and progression of that bacterial contamination. The threshold is not a single point, but rather a transition zone, or state space, of progressive risk for the development of a SSI.

5. Our goal is to provide a general characterization of this state space, using abstract functions associated with virulence, to develop an analytical framework onto which more detailed genomic/transcriptomic microbial analysis can be contextualized in the future. Given the extent of attention paid to the host factors, the current complementary project focuses on investigating the contributions of the microbial component, holding the host response constant as a necessary reference point. However, we clearly recognize that future work will need to include representation and examination of the contribution of various host factors in the state space of risk for SSI.

Developing such a coherent picture of SSIs requires integrating the disparate knowledge bases, with an initial focus of being able to effectively reproduce the process of normal and successful wound healing. The rationale for this is that in order to study a disease state, it is necessary to characterize the state of health from which the disease diverges.6 Mathematical and computational models represent useful translational tools that help synthesize and integrate such knowledge. Dynamic knowledge representation through computational modeling and simulation can augment traditional investigational studies by generating and instantiating novel hypotheses, integrating otherwise disparate information, and bridging gaps in the current knowledge base.7–9 Given that biological systems are generally robust over a wide range of conditions, a qualitative approach to model development using relatively abstracted descriptions of the biological processes can often provide sufficiently useful representations of overall system behavior.6,7,10 Dynamic knowledge representation has been described and validated as a means of “conceptual model verification” in various biological contexts.7

Agent-based modeling is a modeling method that is particularly well suited for dynamic knowledge representation of biomedical systems.11 Agent-based modeling is an object-oriented, rule-based, discrete-event, spatially explicit computational modeling technique that represents systems as aggregates of populations of interacting components, or agents. Computational agents representing individual system components encapsulate computational rules based on published knowledge of their interactions and behavior. A population of agents is simulated in a “virtual world” that can be treated as an in-silico experimental model. Agent-based models (ABMs) for dynamic knowledge representation often contain a significant amount of component-level (i.e., molecular species) detail while being able to use modular functional abstractions and estimations for system kinetics to generate qualitatively valid model/system behavior.11 Agent rules in the ABM are often written as conditional (“if-then”) statements, which are well suited for the representation of hypotheses generated by traditional basic science research. ABM rules can include stochastic components that allow individual agents to have different behavioral trajectories yielding differential population-level dynamics within each run of the ABM. When viewed in aggregate, an overall view of generalized system behavior often emerges. The reliance of ABMs on agent interactions, and hence agent interaction topologies, reinforces the explicit role that space plays in the dynamics of an ABM. As a result, ABMs are well suited to modeling processes that have a significant spatial architecture, such as tissue or organ structures. ABMs have been previously used to study a wide array of inflammation-related processes, including sepsis,12,13 inflammatory cell trafficking,14,15 angiogenesis,16,17 host-pathogen interactions,18–21 and necrotizing enterocolitis.22

These characteristics of an ABM, particularly the cell-centric emphasis and spatial representation capability, make them well suited to the study of wound healing and wound infection, and, as such, there have been a number of published ABMs examining various aspects of wounding and wound healing.23–30 These models have provided insights into the dynamics of injury and repair, aiding in the characterization of normal dermal/epidermal biology,26,27 the healing response in specific disease states,23–25,29 and investigating/integrating existing knowledge of intracellular signaling pathways.28,30 Indeed, agent-based modeling is a mainstay in the application of translational systems biology to wound healing.9,11 As such, agent-based modeling, with its emphasis on characterizing cellular behavior, is a useful adjunct to more traditional, equation-based, continuum mathematical models of wound healing, which have emphasized components/processes such as response to hypoxia, growth factor distribution, and the dynamics of the extracellular matrix.31–41

Clinical Problem Addressed

The current project, which aimed at investigating the dynamics of SSI, differs from previous agent-based modeling work by moving beyond dermal/epidermal biology to examine the effects of injury and healing response on the deeper tissues involved in SSIs, specifically the biology of muscle injury and repair. We choose this tissue level, because very often the development of an SSI is associated with a dermal/epidermal layer that has successfully healed to some degree. Furthermore, those surgical wounds most prone to SSIs are extensive operations that penetrate deep into either a body cavity (peritoneum) or through significant muscular layers (as in orthopedic procedures).1,3,4 Therefore, we believe that one could plausibly consider the muscular tissue layer playing a significant role in the pathogenesis of SSI, and perhaps representing a significant, if not primary, point of host biological activity in the pathogenesis of SSI. We term our ABM of the muscular component of SSI as the Muscle Wound ABM (MWABM). The base MWABM consists of agents representing muscle cells, myoblasts, and various species of immune cells interacting within a simulated matrix of healthy muscle cells containing abstracted blood vessels. To study SSIs, simulated bacteria are added to the base MWABM. Rules governing the various cellular agent types were extrapolated from known signaling pathways in literature. Execution of the MWABM involved repeated iterations (“steps”) where the computational agents interact with other agents and their mutual environment. The output of the MWABM can then be examined at multiple sequential time points, allowing system dynamics to be examined and validated against data from traditional experiments. We recognize that muscle wound healing and infection processes are more complex than currently modeled, and plan to add additional functional cells/components as our research progresses.

We use the MWABM to identify multi-variable threshold zones that mark the phase transition between healing and nonhealing/abscess formation, with the specific emphasis on characterizing the difference in thresholds between aseptic healing, in the presence of avirulent bacteria, and in the presence of bacteria with virulence potential.

Materials and Methods

MWABM implementation

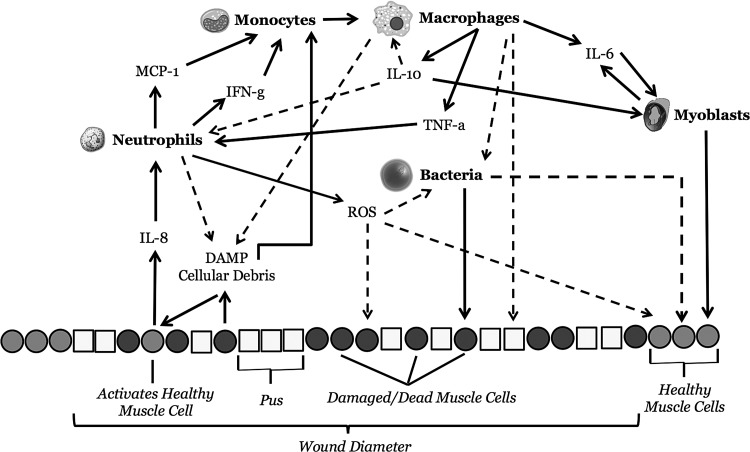

The MWABM was developed by integrating the extensive published data describing cellular and molecular behaviors associated with wound healing, specifically those involving the cellular mechanisms tied to inflammation, debridement, wound closure, and myogenesis.42–69 The next section will be divided into brief descriptions of the behavior rules for neutrophil agents, macrophage agents, individual muscle cell agents, abstracted blood vessels, and both avirulent and virulent bacteria, as well as a description of the overall structure and process overview of the MWABM. An overall schematic of the molecular mechanisms included in the MWABM can be seen in Figure 1. The MWABM was implemented using the freeware agent-based modeling toolkit NetLogo.70 The specific properties and capabilities of NetLogo can be examined by downloading the software at http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo

Figure 1.

Overall schematic of cells, cellular functions mediators present in the MWABM: This figure is a semi-cross section of the MWABM, where the IMC matrix is depicted as a row of healthy IMCs, damaged/dead IMCs, and pus agents at the bottom of the figure. The wound diameter is denoted as a section of this row. Mobile inflammatory cells, migratory myoblasts, and bacteria are seen above the matrix row, along with the mediators produced by and affecting their activity. Solid arrows denote positive/stimulatory effects, whereas dashed arrows denote negative/inhibitory effects. The specific rules associated with each of these interactions can be seen in the Agent types and rules section of Materials and Methods, as well as in Tables 1 and 2. MWABM, Muscle Wound agent-based model.

Overall architecture of the MWABM

The overall architecture of the MWABM involves the representation of an abstracted 2-dimensional section of muscle tissue (Fig. 2A). Abstracted blood vessels were interspersed uniformly throughout the muscle cell matrix. The resultant arrangement represents a single confluent longitudinal muscle cell layer, with each agent mapped to a distinct space (“patch”) on the grid. Mobile agents (immune cells and myoblasts) move over the grid of patches, whereas immobile agents (individual muscle cells) stay on their single patch. Mediators secreted into the tissue environment are represented by variables associated with each patch. Diffusion of mediators in the extracellular matrix is accomplished using the NetLogo function “diffuse,” where the value of the mediator on a patch is distributed at a defined percentage/rate into the eight surrounding patches. Summaries of agent and patch variables are included in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Of note, simulated bacteria are not treated as individual agents, but rather are represented using an aggregated patch variable representing the size of a resident bacterial population. The time scale of the model is such that virtual time represents a distinct amount of real time, in that 1 “tick” of the system corresponds to ∼0.694 min. The size and topology of the MWABM grid is a 49×49 grid, where the edges “wrap” to produce a torus. The radius of the initial injuries, which are centered at the midpoint of the grid (0,0), is the square root of the initial damage size (i.e., number of damaged individual muscle cells). The model was successfully calibrated such that a moderately sized wound (∼217 damage cell intensity), which takes ∼7 days (168 h) to heal, heals in ∼7,000 ticks. Due to the toroidal topology of the MWABM, where diffusing mediators and mobile cells might exit one edge of the model grid and reappear on the opposite edge, thereby accentuating their effects, world-edge/boundary effects were evaluated following parameter sweeps of initial damage intensity to identify the healing-nonhealing transition zone. An evaluation of world-edge effects was performed by increasing the overall world grid size approximately four-fold, from dimensions of 49×49 to 101×101 and performing simulations at the lower bound of nonhealing wound size. The lower bound of nonhealing wound size was chosen, because the primary effect of wound-edge effects would be to accentuate the consequence of damage by reducing the reservoir of healthy tissue/blood vessels from where repairing cells would arrive. These simulations confirmed that world-edge effects were not significant with regard to the outcome goals of the current modeling study (see Results, Identification of the transition zone in the baseline MWABM).

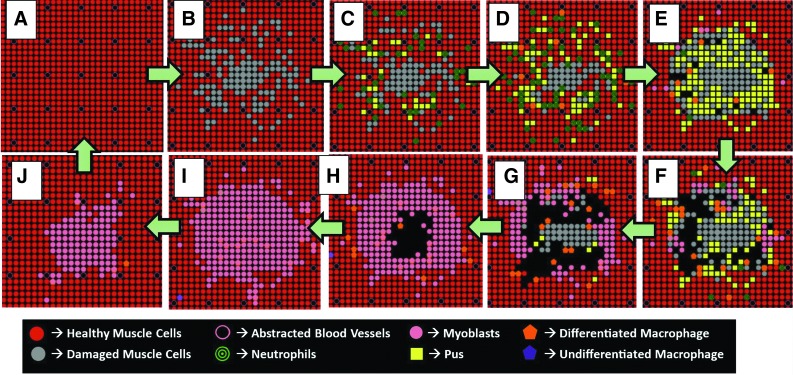

Figure 2.

Series of MWABM screenshots of a single representative run demonstrating successful healing. (A–J) show the progression of the MWABM from healthy (A) with initial injury (B) followed by neutrophil influx and pus generation (C–E), macrophage influx and pus clearance (D–G), and, finally, myoblast influx and muscle regeneration (F–I) until the healthy state is returned (I, J, A). To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Table 1.

List of computational agent types, cell types represented, and role in the Muscle Wound agent-based model

| Agent Type | Cell Type | Effect in MWABM |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil agent | Neutrophils | Consumes damaged cells/bacteria and recruits macrophages, undergoes oxidative burst to produce ROS |

| Macrophage agent | Macrophages | Phagocytizes damaged cells/pus/bacteria and recruits neutrophils and myoblasts; aids in down-regulation of subsequent inflammatory response |

| Myoblast agent | Muscle progenitor cell | Migrates to areas of injury and replaces patches of damaged cells/pus, eventually fuses with muscle cell matrix |

| Bacteria | Avirulent/virulent microbe | Consumes dead muscle cells, attacks healthy tissue, and grows rapidly; affected by immune cell presence and ROS |

| Individual muscle cells | Healthy myocyte | Forms a longitudinal layer of muscle; surface on which damage/infection takes place |

| Abstracted blood vessels | Tissue capillaries | Interspersed uniformly with muscle cells; source of cell recruitment, eliminated via simulated thrombosis in areas of injury |

| Damaged individual muscle cells | Dead/damaged myocyte | Cleared by immune cells; nutrient source for bacteria |

| Pus | Dead neutrophils | Impairs neutrophil movement; removed by macrophages, nutrient source for bacteria |

MWABM, Muscle Wound agent-based model; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Table 2.

List of produced and secreted mediators and cellular products represented in the Muscle Wound agent-based model

| Mediator Variable | Description | Effect in MWABM |

|---|---|---|

| DAMP/cellular debris | Released by damaged IMC agents | Initiate IL-8 secretion by IMC agents; initiate macrophage recruitment differentiation |

| IL-8 | Released by IMC agents activated by DAMP/cellular debris | Recruits neutrophils |

| MCP-1 | Released by activated neutrophil agents | Recruits macrophages |

| IFN-γ | Released by activated neutrophil agents and macrophage agents | Activates macrophage differentiation |

| TNF-α | Released by activated macrophage agents | Recruits neutrophils |

| ROS | Released by activated neutrophil agents | Kills bacteria, degrades damaged muscle cells |

| IL-6 | Released by activated macrophage agents | Recruits myoblasts |

| IL-10 | Released by activated macrophage agents | Initiates down-regulation of subsequent neutrophil and macrophage agents |

DAMP, damage-associated molecular pattern molecules; IL, interleukin; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; IMC, individual muscle cell; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Agent types and rules

Individual muscle cell agent rules

Individual muscles cell (IMC) agents are not mobile, with one IMC agent occupying one grid space in the undamaged MWABM. While they do not move, IMC agents do respond to interactions with other agents as well as alterations in mediator levels in their environment. Their actions are as follows:

1. Activated by exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS), number of bacteria, and damaged associated molecular (DAMP) molecules/cellular debris. When these values are greater than a set threshold value, the IMC agent is considered “damaged.”

2. When activated, they secrete interleukin (IL)-8 for neutrophil recruitment/activation.47

3. When damaged, they release a burst of DAMPs and cellular debris.46,51

4. When sufficiently damaged, they will undergo apoptosis.71

Neutrophil agent rules

Neutrophil agents represent circulating neutrophils that enter the muscle tissue from the blood vessels when activated by cytokines. They then migrate to regions of tissue damage where they secrete additional cytokines and ROS. The primary events have been divided into the following steps:

1. Recruitment/activation by IL-8.47

2. Clearance of DAMP molecules and cellular debris.45

3. Secretion of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) for monocyte (macrophage precursors that reside in the circulation) recruitment.52

4. Secretion of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) for monocyte activation.53

5. Secretion of ROS through oxidative burst to kill not only bacteria but also damage surrounding IMCs.54

6. Phagocytosis of bacteria. After phagocytosis, the neutrophils die and are converted to agents representing pus.

Macrophage agent rules

The role of macrophage agents in the MWABM is to function as a second level of immune response to muscle damage or infection. Not only do they act to propagate inflammation by attracting and activating neutrophils through a positive feedback loop, but they also facilitate debridement/removal of damaged cells and pus through simulated phagocytosis. Macrophage agents in the MWABM are generated from the blood vessels through abstract simulation of monocyte adhesion and migration. They are then activated to differentiate into differentiated macrophages by IFN-γ or large amounts of DAMP and cellular debris. Since we are primarily interested in the relatively early phases of wound healing (before tissue remodeling), we are focusing on the dynamics of the early-phase macrophage subtypes (Type M1). Their primary functions are outlined below:

1. Generated by simulated monocyte recruitment from blood vesselsby MCP-1.52

2. Differentiation into mature macrophages mediated by IFN-γ.53

3. Clearance of damaged cells and pus through phagocytosis.64

4. Secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) for additional simulation of neutrophils.59

5. Secretion of IL-6 for myoblast recruitment.55

6. Secretion of IL-10 to initiate down-regulation of subsequent inflammatory cell response.57,58

Myoblast agent rules

Myoblast agents represent the progenitor cells for the IMCs that are recruited from the circulation, migrate into areas of damaged tissue where debris have been cleared, and subsequently differentiate into mature IMCs.61,65 They originally existed as myosatellite cells (represented in the MWABM as circulating baseline myoblast agents) that on activation by IL-6 migrate into the affected tissue and differentiate into myoblasts.55,60,65 Their primary functions are outlined below:

1. Activation by IL-6, leading to migration from abstracted blood vessels into the tissue and toward the wound following a gradient of IL-6.55,56

2. While migrating (before fusion), they will produce IL-6 in response to stimulation by IL-10.55,60

3. Migration/movement occurs until they encounter a patch that has been cleared of a dead/damaged IMC and/or any bacteria. This represents initial myoblast fusion with the wound matrix and takes place from the wound periphery inward.60,61,65

4. Differentiation into IMCs. This takes place after myoblast fusion with the matrix and takes 2,880 ticks (∼3 days).72

Abstracted blood vessels

As noted earlier, we have implemented abstracted blood vessels at regular intervals in the MWABM tissue. These agents can be considered “end on” blood vessels, and provide a portal of entry for circulating agents into the model world. These simulated blood vessels are able to abstractly perform generally accepted vascular behavior associated with inflammation and healing. They “thrombose” when surrounded by damaged IMC agents, abstractly representing endothelial activation by inflammation and consequent activation of the coagulation cascade.66 They are then able to “recannalize” as a part of the myofibroblast repair and regeneration process, abstractly representing the overall process of revascularization of damaged tissue.63 We note that we have heavily abstracted these processes, and future models may be able to integrate the extensive research in both of these phases with the current focus of the MWABM.

Simulated bacteria

Due to computational constraints (arising from their presence in numbers orders of magnitude greater than eukaryotic host cells), we elect to represent bacterial populations in the MWABM as a single variable associated with each patch. Bacterial populations can be of either avirulent or virulent types.

Avirulent bacteria do not grow on or invade normal healthy IMCs. However, they reproduce rapidly on patches containing damaged or dead IMCs where they represent the bacteria's food source. Bacterial growth on a single patch follows exponential growth that is limited by a carrying capacity which is defined by the amount of resource available (i.e., the number of dead/damaged ICMs). Once carrying capacity is reached on a single patch, bacteria may only disperse into adjacent patches containing damaged IMCs. The exception is that if bacterial growth and numbers are high on multiple patches adjacent to a healthy IMC, the IMC agent will die due to implied lack of nutrition and crowding. In their virulent state, bacteria are more easily able to destroy healthy muscle tissue.

Both neutrophil agents and macrophage agents reduce bacterial levels. Oxidative burst by neutrophil agents allow for the rapid secretion of ROS that kill bacteria. Macrophages also actively phagocytize bacterial agents.

Bacteria with virulence potential are implemented in the MWABM by introducing the possibility of a mutation from the avirulent to the virulent form at an incidence of 1:1,000 produced bacteria. Virulent bacteria display the following characteristics:

1. Increased resistance to killing from immune-cell-produced ROS

2. Increased invasiveness manifested by the ability to kill healthy IMCs

3. Decreased reproduction rate due to increased energy consumption (to manifest virulence factors) and, consequently, less reproductive efficiency. This reflects the increased metabolic cost of expressing virulence factors.

Process overview and sequence of events

At initialization, when no damage is inflicted, the MWABM represents an intact monolayer of undamaged IMC agents. Initial damage is inflicted in the center of the model, and is able to be varied in size (radius of injury being the square root of the injury size), where larger initial injuries reflect a greater number of IMC agents converted from healthy IMC agents into damaged IMC agents in a randomized fashion that issue from the center of the system where IMC agents closer to the center of the system are more likely to be damaged (Fig. 2B). Damage in the MWABM also eliminates abstracted artery agents that are located on a patch which was damaged or adjacent to many damaged patches.

After initial damage was inflicted across the muscle matrix, inflammation rapidly propagates through the activation and attraction of circulating inflammatory cell agents. Large numbers of neutrophil agents propagate the system due to high levels of IL-8 secreted by healthy IMC agents that are located adjacent to the wound. Neutrophils break down damaged IMC agents and remove DAMP and cellular debris. Since the neutrophil agents consume damaged IMC agents, they eventually die and form pus agents. Pus agents impede neutrophil agent movement, making the central core of the wound relatively inaccessible. The rapid secretion of reactive ROS by many neutrophil agents has an adverse effect on healthy IMC agents as well, converting them into damaged IMC agents and causing an initial expansion of the wound (Fig. 2C–E).

Since neutrophil agents are rapidly recruited to the site of the wound, they, in turn, secrete MCP-1, which recruits macrophage agents. Macrophage agents debride the wound environment of pus agents and additional damaged IMCs, resulting from high ROS. Clearance typically takes place at the periphery of the wound and travels toward the center of the system (Fig. 2E–G). While all macrophage agents in the MWABM are originally recruited as monocytes, their differentiation at this stage of the simulation is almost immediate due to high levels of DAMP and cellular debris that still manifest the system. Macrophage agents also secrete TNF-α, which stimulates the proliferation of neutrophils. The secretion of TNF-α creates a positive feedback loop between neutrophils and macrophages that allows for inflammation and clearance to be sustained for longer periods of time.

Macrophages secrete IL-6 that recruits myoblasts to the wound. As macrophages clear pus and damaged muscle, myoblasts proliferate to open patches in the muscle matrix and begin to fuse with the surrounding muscle cells. Similar to clearance, myoblasts enter the wound from the periphery and close the wound from the outside in (Fig. 2G–I). Since the myoblasts fuse into the muscle matrix and differentiate into healthy muscle cells, abstracted artery agents return to areas that were once devoid of capillaries. Once myoblast fusion is complete, the MWABM returns to its state before damage (Fig. 2I, J, A).

Inclusion of bacterial infection to MWABM

The application of the bacterial inoculum in the MWABM is generalized to be the addition of bacteria to every patch containing damaged muscle cells. This is based on the assumption that bacteria would adhere primarily to damaged muscle as opposed to healthy muscle.

Identification of transition zones between successful and nonsuccessful/infection healing

After development of the MWABM, a series of simulation experiments was performed to characterize the transition zones between successful healing and healing failure. The initial experiments were performed to assess the dynamics of the baseline MWABM in the absence of any bacterial involvement. These simulations involved performing a parameter sweep over a range of initial damage values from 200 to 400 cells with 10 cell increments. The extent of healing for each run (10 runs for each damage intensity) was accessed for each run after 1 week (168 h) where a “healed” outcome was considered the complete restoration of the baseline MWABM IMC matrix. Next, the effect of avirulent bacteria was examined by performing a parameter sweep of initial injury as conducted earlier, but with the addition of an initial bacterial load of 100 bacteria onto the damaged tissue. Finally, the effect of virulence potential in the bacterial population was evaluated by performing a parameter sweep of initial injury over a range of wound sizes (150 damaged cells to 350 damaged cells with 10 cell increments) with similar endpoints as noted earlier (1 week or 168 h simulated time, healed endpoint being complete restitution of IMC matrix), but this time including an initial inoculation of 100 bacteria with the capacity to express virulence factors every 1:1,000 replications.

Results

Observed system dynamics

The MWABM qualitatively reproduced muscle wound healing dynamics. The activation and recruitment of various immune cells (neutrophils and macrophages) coupled with the recruitment of progenitor muscle cell agents (myoblasts) led to debridement of the wound area as well as wound closure due to the proliferation of differentiated myoblasts. In interpreting the output of the MWABM, it is important to note that since the MWABM is constructed as an integrated dynamic representation of knowledge, it is inevitable that there will be data curves for which validating experimental data do not yet exist. The key here is that, through known relationships identified in the literature and represented in the MWABM's conceptual model, the dynamics of mediators not yet deeply investigated may be posited, and potentially suggest additional targets to be assayed: Doing so would aid in either the validation or falsification of the underlying hypothesis structure instantiated in the model. As a result, in presentation of the MWABM simulation experiments below, corresponding references related to simulated mediator and cell population dynamics (generally qualitative, and drawn from associated processes such as dermal wound healing or exercise-induced muscle injury) will be presented when available.

As a representative example, we demonstrate the system dynamics of the MWABM observed by inflicting a 217 cell damage across the muscle matrix (Fig. 3). Additional simulations indicated that specific time points and peak signal intensity levels increased with greater damage intensity; however, the general trend of signal transduction and regulation remained relatively consistent.

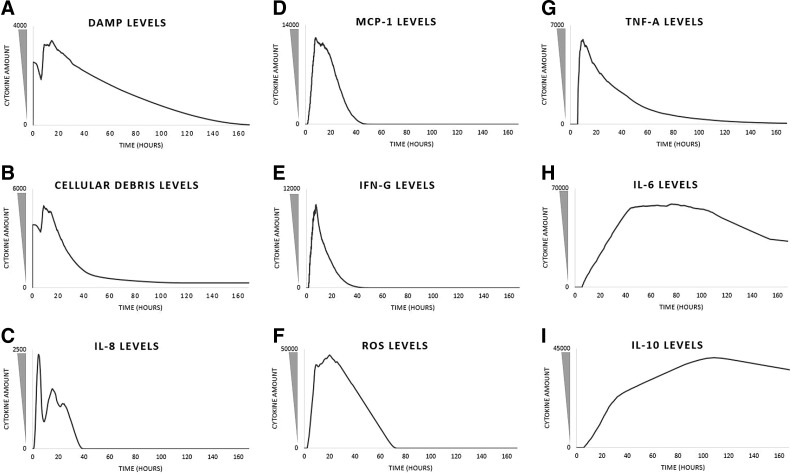

Figure 3.

Time courses of mediators present in a representative healing run of the MWABM. These graphs (A–I) depict the system-wide values of the respective mediators present in the MWABM in the same run that produced the screenshots in Figure 2. The values themselves are unitless and not calibrated to actual metrics, but are qualitatively valid in relation to each other.

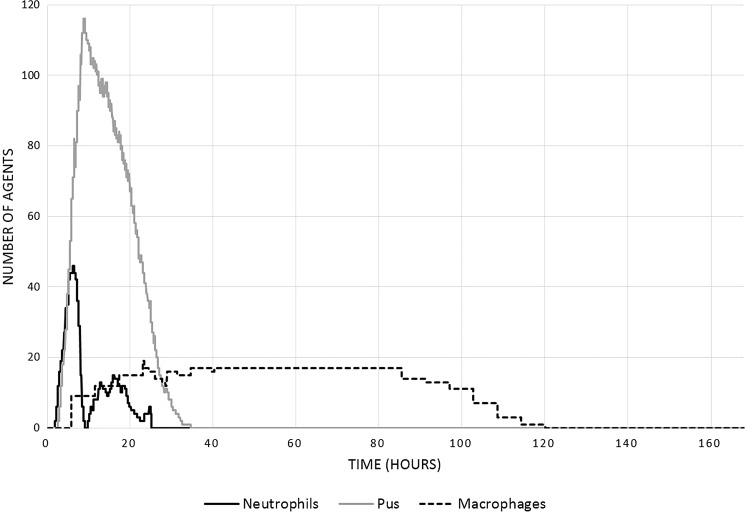

Temporally, the DAMP and cellular debris signal reaches a local maxima when the simulation begins (0 h) as a result of the initial damage inflicted before the start of the simulation (Fig. 3A, B). The high levels of DAMP and cellular debris cause the IL-8 signal to reach its peak intensity at ∼5.1 h due to the increased secretion of IL-8 by ICM agents adjacent to the wound (Fig. 3C).62 The signal peak of IL-8 initiates the rapid proliferation of neutrophil agents, which reaches peak system presence at about 5.4 h (Fig. 4).62,67,68 The secretion of ROS by these neutrophil agents develops a large amount of pus. ROS secretions increase rapidly for at least 20 h post damage (Fig. 3F).67 ROS at high concentrations creates pus, which peaks at 9 h (Fig. 4). The rapid increase of systemic ROS levels affects some healthy muscle cells, which die as a result. The death of these healthy muscle cells can be observed by noting peak levels of DAMP and cellular debris at 10–12 h (Fig. 3A, B). Besides secreting ROS, neutrophil agents also secrete MCP-1, which recruits macrophages. MCP-1 levels peak at about 8.3 h, and result in the rapid proliferation of macrophages to the wound for about 24 h (Figs. 3D and 4).62,68,73 To initiate macrophage differentiation, neutrophil agents secrete IFN-γ, which reaches peak intensity at 8.4 h (Fig. 3E). Note that this maximum coincides well with the time point for maximum initial macrophage recruitment at 8.3 h.67,68 The MWABM indicates this differentiation by alternating the colors of respective macrophages. Orange macrophage agents indicate IFN-γ activation, while purple macrophage agents indicate no activation (Fig. 2). While neutrophils stimulate macrophage differentiation, macrophages stimulate neutrophil proliferation through secretion of TNF-α. TNF-α production reaches a systemic maximum at 10.8 h, and causes a rapid rise in neutrophil levels as well as a local peak in neutrophil amounts at about 17 h (Figs. 3G and 4).67,73,74 Macrophage agents secrete two other cytokines (IL-6 and IL-10) that contribute to wound closure and down-regulation, respectively. IL-6 levels reach high levels at 43 h and allow for the recruitment of myoblasts, which reach peak systemic amounts at 55 h (Figs. 3H and 5).75 IL-10 levels reach a maximum at 108 h and allow for the down-regulation of the healing process as a whole (Fig. 3I). We note that there is discrepancy between the MCP-1 and macrophage population time courses when compared with some of our reference studies;62,68 we believe that this is due to the fact that the current MWABM does not include TH1/2 lymphocyte subtypes, which are greatly responsible for a shift in the macrophage populations from M1 to M2 subtypes.68 Nevertheless, the conceptual model/hypothesis structure instantiated in the current MWABM appears to be sufficient in linking acute inflammatory processes to the myoblast infiltration that is necessary for wound healing. We will discuss further implications of this discrepancy in the Discussion section.

Figure 4.

Time course of cellular populations of neutrophils, macrophages, and pus in a representative healing run of the MWABM. These cell populations were generated from the same run that produced the screenshots in Figure 2 and the graphs in Figure 3.

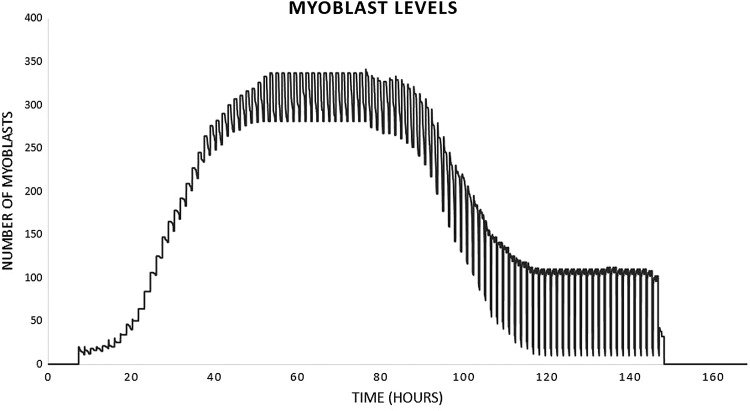

Figure 5.

Time course of myoblast populations in a representative healed run of the MWABM. The regular oscillation in the population level is an artifact of the code scheduler in the NetLogo implementation; myoblast levels can be considered the mean of the oscillation amplitude. This cell population corresponds to the graphs seen in Figure 3.

Identification of the transition zone in the baseline MWABM

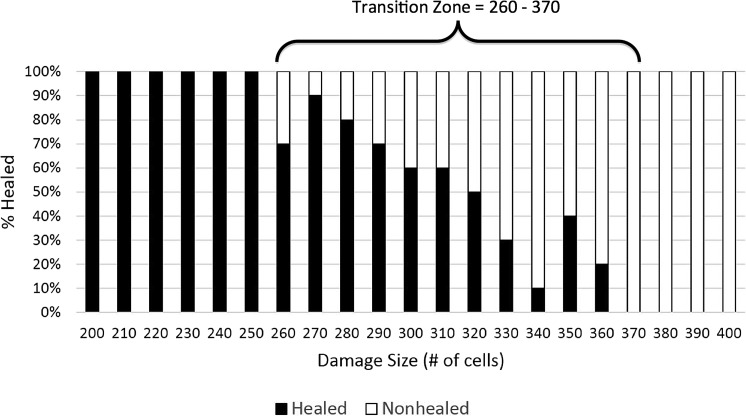

Beyond a certain size, the initial damage can be too great for the system's immune response to adequately remedy the situation. At a damage size of 260, only 70% of wounds heal in the MWABM (Fig. 6). As the damage intensifies, the proportion of healed wounds gradually decreases. At a damage intensity of 320 cells, 50% of wounds heal, while 50% are nonhealed after 1 week. By a damage intensity of 370, 100% of wounds do not heal by the end of 1 week, as the wound is too extensive for the healing process to succeed. Due to the toroidal topology of the MWABM, the effect of world-edge wrapping on the upper bound of the transition zone from healing to nonhealing was evaluated by increasing the overall world grid approximately four-fold, from dimensions of 49×49 to 101×101. Repeat runs with damage intensities of 370 and 380 demonstrated 100% nonhealing at 7 days (n=10), and, therefore, with no alteration of the healing/nonhealing transition zone. While world-edge effects may be present at higher initial damage intensities, given the focus of the current MWABM project, we conclude that for purposes of these simulations world-edge effects are not significant, in terms of identifying shifts in the transition zone due to bacterial effects, which involved shift towards smaller initial damage intensities.

Figure 6.

Depiction of transition zone between healed and nonhealed/SSI outcomes in the base MWABM (no bacteria). This figure demonstrates the results of a parameter sweep of initial injury size (# of cells damaged in increments of 10), with an n=10 for each initial injury size. The transition zone is defined as extending from the initial injury size at which nonhealing is first seen to the injury size at which no healing is seen at all. This parameter sweep in the base MWABM (without any bacteria) is done to establish the “normal” case from which pathogenic conditions can be assessed. The transition zone in this case extends from 260 to 360 initial damage size.

Effect of bacterial infection on wound healing

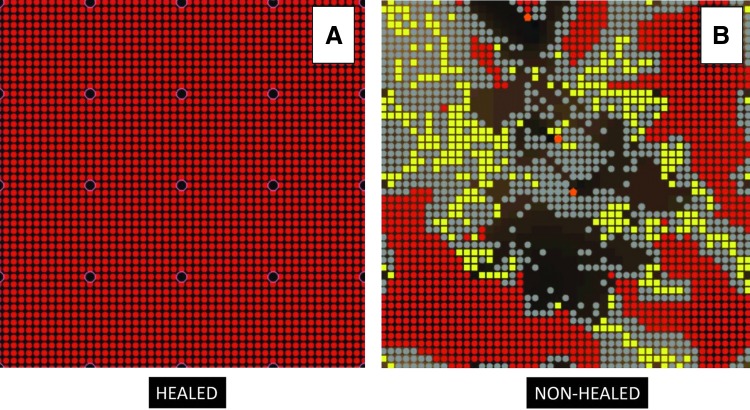

The application of bacterial inoculum to the wound dramatically affected the transition zone between healed and nonhealed phenotypes. A typical healed morphology is the regular, uniform muscle matrix that is identical to the matrix before damage (Fig. 7A). The unhealed morphology contains a distinct abscess as well as significant areas of necrotic debris that remain uncleared (Fig. 7B). Results of the parameter sweep identified lapses in the healing ability of the MWABM starting at a damage intensity of 210 cells (Fig. 8). Compared with normal wound healing, this represented a left shift in terms of the healing tipping point by 50 cells. The 50% healed threshold mark is observed at 275 cells, a −45 cell difference compared with normal wound healing. By a damage intensity of 320 cells, 100% of wounds did not heal, representing a −50 cell difference compared with normal wound healing.

Figure 7.

Screenshots of both successfully healed MWABM run (A) and an SSI (B). These images depict the healing and SSI phenotypes as seen in the MWABM. In particular, note the highly irregular shape of the SSI phenotype; this reflects a loss of effective containment of the initial injury, and reinforces the spatial nature of the wound healing process. SSI, surgical site infection. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Figure 8.

Depiction of transition zone between healed and nonhealed/SSI outcomes in the MWABM with avirulent bacteria. This parameter sweep was performed in the same manner as the simulations used to generate Figure 6, but with the addition of 100 avirulent bacteria with the initial damage. The notable finding here is that the transition zone underwent a left shift to damage size 210 to 320, suggesting the detrimental effect of bacterial contamination on the effectiveness of wound healing manifesting as an SSI. Also of note, the size of the transition zone (90 damaged cells) is relatively similar to the size of the baseline transition zone (100 damaged cells).

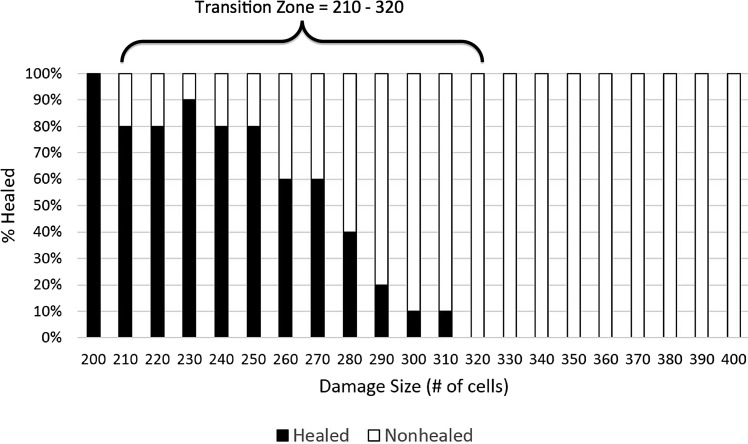

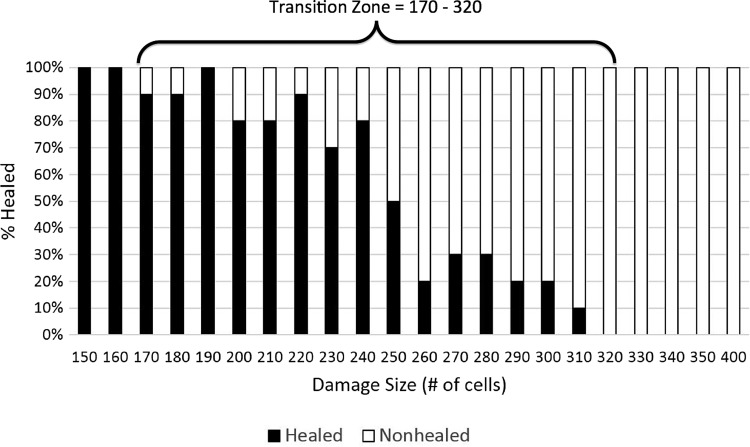

Effect of bacterial virulence potential on wound healing

The presence of virulence potential in the bacterial population also affected the transition zone between successful healing and the development of an abscess, with a further left shift in the size of initial injury that could lead to abscess formation. Lapses in wound healing were seen in wounds as small as 170 cells (Fig. 9). Compared with normal wound healing, this represents a difference of −150 cells, and compared with wound healing with avirulent bacteria, this represents a difference of −60 cells. The 50% healed threshold mark is observed at 250 cells, which is a −70 cell difference compared with normal wound healing and a −25 cell difference compared with wound healing with avirulent bacteria. Interestingly, the upper edge of the transition zone where 100% nonhealed morphology on all runs is observed at 320 cells is identical to wound healing with avirulent bacteria. This finding suggests that virulence potential may have its greatest effect in increasing the host population at risk for developing SSI. In addition, since the upper threshold of the transition zone reflects the upper extent of the degree of contamination and the lower threshold reflects the lower bound of contamination, given the attention paid to antisepsis, it is plausible to assume that a large percentage of unanticipated SSIs would most likely occur near the lower bound. This suggests that the role of bacterial virulence potential has a disproportionate effect in the clinical pathogenesis of SSI.

Figure 9.

Depiction of transition zone between healed and nonhealed/SSI outcomes in the MWABM with virulent bacteria. This parameter sweep was performed in the same fashion as the simulations used to generate Figure 8, but with the addition of dynamic virulence potential (arising 1:1,000 bacteria productions). The notable finding here is that while the upper threshold of the transition zone (Damage #=320), reflecting the upper extent of contamination, is the same as with avirulent bacteria, the lower threshold (Damage #=170), reflecting the lower bound of contamination, is considerably less. Given the attention paid to antisepsis, it is plausible to assume that a large percentage of unanticipated SSIs would occur at the lower bound, suggesting that the role of bacterial virulence potential has a disproportionate effect in the clinical pathogenesis of SSI.

Discussion

Wound healing is a complex process that requires the collaborative efforts of various cell types during the phases of inflammation, debridement, wound closure, and myogenesis for the successful healing of a muscle wound. Understanding the mechanisms involved in wound healing provides the foundation for the study of SSIs. However, knowledge concerning the multiple cell signaling pathways and various cellular interactions involved is scattered throughout the literature and presents a challenge to attempts to produce a cohesive picture of the wound healing process. Agent-based modeling is a useful means of integrating disparate mechanistic knowledge, and herein we describe an ABM that integrates known mechanistic components of muscular wound healing, the MWABM.

Simulations with the MWABM qualitatively reproduce recognizable patterns of wound healing. Wound closure and myoblast proliferation travel from the periphery of the wound inward through the described intracellular, cell–cell, and cell–matrix interactions in a plausible fashion. The existence of a transition zone between healing and nonhealing is, given the time span of these simulations, also plausible. As noted earlier, the ability to characterize the baseline normal state is essential to be able to incorporate and contextualize the factors that can negatively affect the system. This was the case in the simulations involving first the avirulent bacteria and then the bacteria with virulence potential. As expected, the presence of any bacteria could, by inducing the production of pus through the activity of the neutrophils, generate spatial zones within the wound that impaired myoblast migration and maturation. The increase activity of neutrophils also led to increased collateral tissue damage, sustaining the pro-inflammatory state and further impairing effective repair.

Simulations involving the introduction of virulence potential further accentuated the negative dynamics of the MWABM. The key point in these simulated experiments, however, is the demonstration that it is the dynamic expression of virulence in the bacterial population which plays a key role in increasing the likelihood of an SSI. This is important, because it places greater importance on being able to utilize the higher resolution analysis that is now available through genetic profiling of microbial species; it is no longer sufficient to provide a general identification of a particular bacterial species (or even a single property such as antibiotic resistance), but rather what is required is a characterization of what the microbe might be capable of doing in the future. The current simulation experiments focus on being able to represent this virulence potential in terms of generational genetic potential within the entire population, thus capturing the high degree of genetic plasticity present in the prokaryotic kingdom and utilizing the evolutionary process of selection to generate shifts in fitness and capabilities. However, it is increasingly recognized that microbes have extensive environmental sensing capabilities (such as quorum sensing or phosphate responsiveness) which allow for the possibility of more directed virulence activation (as opposed to just relying on fitness and selection).76 If this is the case, then there is an additional layer of complexity possible, as the contaminating microbes may have the ability to sense and respond to environmental cues arising from the host. In this circumstance, the circle of causality in the mechanistic pathogenesis of SSIs can potentially be closed as host activates microbe, microbe attacks host, triggering a greater response to microbe, and so on.76

However, the future study of these complex interactions will almost certainly require the application of “systems” approaches, of which the MWABM is a preliminary example. Central to the utility of ABMs for dynamic knowledge representation is the ability to instantiate and evaluate complex hypothesis structures, both in order to determine their sufficiency, and also to guide identification of points of failure. For example, the current MWABM does not match some existing data concerning the dynamics of macrophage populations.68 Interestingly, while the MWABM's component agent behavior fairly closely matches the dynamics of M1 (early phase) macrophages, it does not capture the trajectories of M2 (late phase) macrophages. In actuality, this can be readily explained by the fact that the current MWABM does not incorporate T-lymphocytes (subtypes TH1/2), which help drive the generation and behavior of the M2 cells.64,68 Nonetheless, despite missing this component, the MWABM appears to sufficiently heal its wounds. We can draw two distinct, but complementary, conclusions from this discrepancy: (1) that the current MWABM constitutes a minimally sufficient hypothesis structure for the initial phases of muscle wound healing, and that (2) there may be, and in fact likely are, circumstances where the lack of this component would cause the MWABM to exhibit nonplausible global behavior (*Note that the behavior referred to in this sentence is overall healing/nonhealing as opposed to matching sub-component population trajectories). Therefore, in the context of the role of the MWABM, a subsequent experimental goal would be to identify cases where the MWABM could be further “broken,” thus demonstrating the need to incorporate additional components in order to render it plausible. Interestingly, the role of IL-10 is ambiguous in the wound healing literature,69,77 and it is notable that it, along with Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13, is responsible for the transition to M2 macrophages.64,68 Speculatively, this may suggest that the later macrophage populations may not be necessary for the initial healing process (the current focus of the MWABM), but rather may represent a modulating control mechanism for later effects, such as scar formation or remodeling. One future avenue of investigation of the effects of host–pathogen interactions on surgical site healing might be to examine the role of bacterial effects, short of gross infection, on these downstream processes related to scar formation.

Key Findings.

• Ability of the MWABM to generate plausibly realistic dynamics of muscular wound healing and the pathogenesis of SSI.

• The MWABM can functionally identify a zone of transition between successful healing and nonhealing/SSI based on initial injury size.

• The MWABM can functionally quantify the effects of avirulent bacterial contamination through shifts in the transition zone between healing and SSI.

• The MWABM demonstrates that the primary effect of the addition of bacterial virulence potential is by increasing the population at risk for developing an SSI.

• The modular architecture of the MWABM allows it to be expanded to include additional mechanistic detail as needed for future investigations.

Our additional current plans for future work with the MWABM include simulation experiments that are intended to achieve higher-level resolution characterization, in terms of cell population and mediator dynamics, of the difference between healing and nonhealing wounds, and the effect of different bacterial virulence patterns on those characteristics. We anticipate that the simulation time courses of cell populations and mediators will guide sampling intervals in the experiments performed by our collaborators, with the dual aim of enhancing model validation and increasing experimental efficiency. Going forward, the hope is that the MWABM will serve as an integrating framework to which, through integration into the traditional experimental workflow, much more detail can be added, and can, thus, substantively aid future inquiry into possible mechanisms of wound healing.

Innovation

Computational modeling can play an important role in integrating, contextualizing, and dynamically visualizing the extensive output of mechanistic knowledge generated from traditional basic research on the pathophysiology of wound healing. Specifically, the MWABM represents the first application of agent-based modeling to the study of the dynamics of SSI with an emphasis on being able to represent the dynamics of virulence activation within the microbial component. The MWABM represents the initial step in the development of a dynamic knowledge representation framework into which the more detailed knowledge generated through cutting-edge omics analysis can be integrated and contextualized, thereby bringing together the various research communities studying inflammation, angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and microbiology.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ABM

agent-based model

- DAMP

damage associated molecular pattern molecules

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- IL

interleukin

- IMC

individual muscle cell

- M1, M2

subtypes of macrophage

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- MWABM

Muscle Wound agent-based model

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SSI

surgical site infection

- TH1, TH2

subtypes of T-lymphocyte

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

The authors wish to acknowledge their basic science collaborators at the University of Chicago, Drs. John Alverdy and Olga Zaborina, for discussions concerning their ongoing basic science work on the role of dynamic bacterial virulence and host-pathogen interactions in the pathogenesis of SSI.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

The authors have no competing interests to disclose. V.G. was the primary developer of the MWABM and the article, M.K. aided in the development of the MWABM, and G.A. aided in the development of the MWABM and preparation of the article. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Vissagan Gopalakrishnan is currently an Undergraduate Student at Johns Hopkins University. He was a visiting student at the University of Chicago over the summers of 2011 and 2012, at which time the work reflected in this paper was performed. Moses Kim, MD, is a surgical resident in the University of Chicago surgical training program. He obtained his BS and MD from the University of Miami, Florida, and is a graduate of the University of Chicago's Fellowship in Translational Systems Biology. Gary An, MD, is an Associate Professor of Surgery, Co-Director of the Surgical Intensive Care Unit and Senior Fellow of the Computation Institute at the University of Chicago. He obtained his BS and MD from the University of Miami, Florida. He did his general surgical residency at the University of Illinois, Chicago/Cook County Hospital training program, and did his surgical critical care fellowship at Cook County Hospital.

References

- 1.Barie PS. Surgical site infections: epidemiology and prevention. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2002;3(Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.1089/sur.2002.3.s1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruse P. Wound infection surveillance. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:734. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.4.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson DJ. Surgical site infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2011;25:135. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owens CD. Stoessel K. Surgical site infections: epidemiology, microbiology and prevention. J Hosp Infect. 2008;70(Suppl 2):3. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(08)60017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esposito S. Immune system and surgical site infection. J Chemother. 2011;S1:12. doi: 10.1179/joc.2001.13.Supplement-2.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vodovotz Y. An G. Systems biology and inflammation. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;662:181. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-800-3_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An G. Dynamic knowledge representation using agent-based modeling: ontology instantiation and verification of conceptual models. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;500:445. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-525-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vodovotz Y. Constantine G. Rubin J. Csete M. Voit EO. An G. Mechanistic simulations of inflammation: current state and future prospects. Math Biosci. 2009;217:1. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An GC. Translational systems biology using an agent-based approach for dynamic knowledge representation: an evolutionary paradigm for biomedical research. Wound Repair Regen. 2010;18:8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An G. A model of TLR4 signaling and tolerance using a qualitative, particle-event-based method: introduction of spatially configured stochastic reaction chambers (SCSRC) Math Biosci. 2009;217:43. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An G. Mi Q. Dutta-Moscato J. Vodovotz Y. Agent-based models in translational systems biology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2009;1:159. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An G. Agent-based computer simulation and sirs: building a bridge between basic science and clinical trials. Shock. 2001;16:266. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An G. In silico experiments of existing and hypothetical cytokine-directed clinical trials using agent-based modeling. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2050. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139707.13729.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey AM. Lawrence MB. Shang H. Katz AJ. Peirce SM. Agent-based model of therapeutic adipose-derived stromal cell trafficking during ischemia predicts ability to roll on P-selectin. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey AM. Thorne BC. Peirce SM. Multi-cell agent-based simulation of the microvasculature to study the dynamics of circulating inflammatory cell trafficking. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:916. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorne BC. Bailey AM. Benedict K. Peirce-Cottler S. Modeling blood vessel growth and leukocyte extravasation in ischemic injury: an integrated agent-based and finite element analysis approach. J Crit Care. 2006;21:346. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer AL. Jackson TL. Jiang Y. A cell-based model exhibiting branching and anastomosis during tumor-induced angiogenesis. Biophys J. 2007;92:3105. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer AL. Beauchemin CA. Perelson AS. Agent-based modeling of host-pathogen systems: the successes, challenges. Inf Sci (NY) 2009;179:1379. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seal JB. Alverdy JC. Zaborina O. An G. Agent-based dynamic knowledge representation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence activation in the stressed gut: towards characterizing host-pathogen interactions in gut-derived sepsis. Theor Biol Med Model. 2011;8:33. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-8-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marino S. El-Kebir M. Kirschner D. A hybrid multi-compartment model of granuloma formation and T cell priming in tuberculosis. J Theor Biol. 2011;280:50. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segovia-Juarez JL. Ganguli S. Kirschner D. Identifying control mechanisms of granuloma formation during M. tuberculosis infection using an agent-based model. J Theor Biol. 2004;231:357. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim M. Christley S. Alverdy JC. Liu D. An G. Immature oxidative stress management as a unifying principle in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis: insights from an agent-based model. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2012;13:18. doi: 10.1089/sur.2011.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li NY. Verdolini K. Clermont G. Mi Q. Rubinstein EN. Hebda PA. Vodovotz Y. A patient-specific in silico model of inflammation and healing tested in acute vocal fold injury. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li NY. Vodovotz Y. Hebda PA. Abbott KV. Biosimulation of inflammation and healing in surgically injured vocal folds. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119:412. doi: 10.1177/000348941011900609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mi Q. Riviere B. Clermont G. Steed DL. Vodovotz Y. Agent-based model of inflammation and wound healing: insights into diabetic foot ulcer pathology and the role of transforming growth factor-beta1. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:671. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christley S. Lee B. Dai X. Nie Q. Integrative multicellular biological modeling: a case study of 3D epidermal development using GPU algorithms. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:107. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker DC. Hill G. Wood SM. Smallwood RH. Southgate J. Agent-based computational modeling of wounded epithelial cell monolayers. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci. 2004;3:153. doi: 10.1109/tnb.2004.833680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stern JR. Christley S. Zaborina O. Alverdy JC. An G. Integration of TGF-beta- and EGFR-based signaling pathways using an agent-based model of epithelial restitution. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:862. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adra S. Sun T. MacNeil S. Holcombe M. Smallwood R. Development of a three dimensional multiscale computational model of the human epidermis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y. Hoenig JD. Malin KJ. Qamar S. Petrof EO. Sun J. Antonopoulos DA. Chang EB. Claud EC. 16S rRNA gene-based analysis of fecal microbiota from preterm infants with and without necrotizing enterocolitis. ISME J. 2009;3:944. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xue C. Friedman A. Sen CK. A mathematical model of ischemic cutaneous wounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909115106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geris L. Schugart R. Van Oosterwyck H. In silico design of treatment strategies in wound healing and bone fracture healing. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2010;368:2683. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flegg JA. Byrne HM. Flegg MB. McElwain DL. Wound healing angiogenesis: the clinical implications of a simple mathematical model. J Theor Biol. 2012;300:309. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segal RA. Diegelmann RF. Ward KR. Reynolds A. A differential equation model of collagen accumulation in a healing wound. Bull Math Biol. 2012;74:2165. doi: 10.1007/s11538-012-9751-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menon SN. Flegg JA. McCue SW. Schugart RC. Dawson RA. McElwain DL. Modelling the interaction of keratinocytes and fibroblasts during normal and abnormal wound healing processes. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279:3329. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy KE. McCue SW. McElwain DL. Clinical strategies for the alleviation of contractures from a predictive mathematical model of dermal repair. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:194. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wearing HJ. Sherratt JA. Keratinocyte growth factor signalling: a mathematical model of dermal-epidermal interaction in epidermal wound healing. Math Biosci. 2000;165:41. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(00)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen L. Sherratt JA. Maini PK. Arnold F. A mathematical model for the capillary endothelial cell-extracellular matrix interactions in wound-healing angiogenesis. IMA J Math Appl Med Biol. 1997;14:261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherratt JA. Murray JD. Mathematical analysis of a basic model for epidermal wound healing. J Math Biol. 1991;29:389. doi: 10.1007/BF00160468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posta F. Chou T. A mathematical model of intercellular signaling during epithelial wound healing. J Theor Biol. 2010;266:70. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Filion RJ. Popel AS. A reaction-diffusion model of basic fibroblast growth factor interactions with cell surface receptors. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:645. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000030231.88326.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ashley MP. Kotlarski I. Vari F. Defects in tumor cell immunogenicity: lymphokine signals in in vitro cytolytic responses to tumor alloantigens. Cell Immunol. 1987;106:151. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(87)90158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bolmstedt A. Hinkula J. Rowcliffe E. Biller M. Wahren B. Olofsson S. Enhanced immunogenicity of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env DNA vaccine by manipulating N-glycosylation signals. Effects of elimination of the V3 N306 glycan. Vaccine. 2001;20:397. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Earl PL. Hugin AW. Moss B. Removal of cryptic poxvirus transcription termination signals from the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope gene enhances expression and immunogenicity of a recombinant vaccinia virus. J Virol. 1990;64:2448. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2448-2451.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujisawa T. Abu-Ghazaleh R. Kita H. Sanderson CJ. Gleich GJ. Regulatory effect of cytokines on eosinophil degranulation. J Immunol. 1990;144:642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janeway C. Immunogenicity signals 1,2,3…and 0. Immunol Today. 1989;10:283. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(89)90081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kunkel SL. Standiford T. Kasahara K. Strieter RM. Interleukin-8 (IL-8): the major neutrophil chemotactic factor in the lung. Exp Lung Res. 1991;17:17. doi: 10.3109/01902149109063278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lasaro MO. Ertl HC. Potentiating vaccine immunogenicity by manipulating the HVEM/BTLA pathway and other co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory signals of the immune system. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:6. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.1.6399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paccez JD. Nguyen HD. Luiz WB. Ferreira RC. Sbrogio-Almeida ME. Schuman W. Ferreira LC. Evaluation of different promoter sequences and antigen sorting signals on the immunogenicity of Bacillus subtilis vaccine vehicles. Vaccine. 2007;25:4671. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piechocki MP. Pilon SA. Kelly C. Wei WZ. Degradation signals in ErbB-2 dictate proteasomal processing, immunogenicity, resist protection by cis glycine-alanine repeat. Cell Immunol. 2001;212:138. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubartelli A. Lotze MT. Inside, outside, upside down: damage-associated molecular-pattern molecules (DAMPs) and redox. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:429. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soehnlein O. Lindbom L. Weber C. Mechanisms underlying neutrophil-mediated monocyte recruitment. Blood. 2009;114:4613. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-221630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belardelli F. Role of interferons and other cytokines in the regulation of the immune response. APMIS. 1995;103:161. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halliwell B. Reactive oxygen species in living systems: source, biochemistry, and role in human disease. Am J Med. 1991;91:14S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cantini M. Massimino ML. Rapizzi E. Rossini K. Catani C. Dalla Libera L. Carraro U. Human satellite cell proliferation in vitro is regulated by autocrine secretion of IL-6 stimulated by a soluble factor(s) released by activated monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;216:49. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Austin L. Burgess AW. Stimulation of myoblast proliferation in culture by leukaemia inhibitory factor and other cytokines. J Neurol Sci. 1991;101:193. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(91)90045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fiorentino DF. Zlotnik A. Mosmann TR. Howard M. O'Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Waal Malefyt R. Abrams J. Bennett B. Figdor CG. de Vries JE. Interleukin 10(IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shau H. Roberts RL. Tumor necrosis factor stimulation of neutrophils for antitumor activity. Immunol Ser. 1992;57:523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abmayr SM. Balagopalan L. Galletta BJ. Hong SJ. Cell and molecular biology of myoblast fusion. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;225:33. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(05)25002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cornelison DD. Context matters: in vivo and in vitro influences on muscle satellite cell activity. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:663. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Engelhardt E. Toksoy A. Goebeler M. Debus S. Brocker EB. Gillitzer R. Chemokines IL-8, GROalpha, MCP-1, IP-10, and Mig are sequentially and differentially expressed during phase-specific infiltration of leukocyte subsets in human wound healing. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1849. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65699-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leibovich SJ. Wiseman DM. Macrophages, wound repair and angiogenesis. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1988;266:131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murray PJ. Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:723. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Siegel AL. Kuhlmann PK. Cornelison DD. Muscle satellite cell proliferation and association: new insights from myofiber time-lapse imaging. Skelet Muscle. 2011;1:7. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thorgeirsson G. Robertson AL., Jr The vascular endothelium-pathobiologic significance. Am J Pathol. 1978;93:803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R345. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00454.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tidball JG. Villalta SA. Regulatory interactions between muscle and the immune system during muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1173. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00735.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamamoto T. Eckes B. Krieg T. Effect of interleukin-10 on the gene expression of type I collagen, fibronectin, and decorin in human skin fibroblasts: differential regulation by transforming growth factor-beta and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281:200. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilensky U. Rand W. An Introduction to Agent-Based Modeling: Modeling Natural, Social and Engineered Complex Systems with NetLogo. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Primeau AJ. Adhihetty PJ. Hood DA. Apoptosis in heart and skeletal muscle. Can J Appl Physiol. 2002;27:349. doi: 10.1139/h02-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kadi F. Charifi N. Denis C. Lexell J. Andersen JL. Schjerling P. Olsen S. Kjaer M. The behaviour of satellite cells in response to exercise: what have we learned from human studies? Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:319. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gillitzer R. Goebeler M. Chemokines in cutaneous wound healing. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Warren GL. Hulderman T. Jensen N. McKinstry M. Mishra M. Luster MI. Simeonova PP. Physiological role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in traumatic muscle injury. FASEB J. 2002;16:1630. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0187fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grellner W. Georg T. Wilske J. Quantitative analysis of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha) in human skin wounds. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;113:251. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seal JB. Morowitz M. Zaborina O. An G. Alverdy JC. The molecular Koch's postulates and surgical infection: a view forward. Surgery. 2010;147:757. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eming SA. Werner S. Bugnon P. Wickenhauser C. Siewe L. Utermöhlen O. Davidson JM. Krieg T. Roers A. Accelerated wound closure in mice deficient for interleukin-10. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:188. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]