Abstract

Purpose

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is major cause of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Atorvastatin is a potent immunomodulatory agent that holds promise as a novel and safe agent for acute GVHD prophylaxis.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a phase II trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of atorvastatin administration for GVHD prophylaxis in both adult donors and recipients of matched sibling allogeneic HCT. Atorvastatin (40 mg per day orally) was administered to sibling donors, starting 14 to 28 days before the anticipated first day of stem-cell collection. In HCT recipients (n = 30), GVHD prophylaxis consisted of tacrolimus, short-course methotrexate, and atorvastatin (40 mg per day orally).

Results

Atorvastatin administration in healthy donors and recipients was not associated with any grade 3 to 4 adverse events. Cumulative incidence rates of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD at days +100 and +180 were 3.3% (95% CI, 0.2% to 14.8%) and 11.1% (95% CI, 2.7% to 26.4%), respectively. One-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD was 52.3% (95% CI, 27.6% to 72.1%). Viral and fungal infections were infrequent. One-year cumulative incidences of nonrelapse mortality and relapse were 9.8% (95% CI, 1.4% to 28%) and 25.4% (95% CI, 10.9% to 42.9%), respectively. One-year overall survival and progression-free survival were 74% (95% CI, 58% to 96%) and 65% (95% CI, 48% to 87%), respectively. Compared with baseline, atorvastatin administration in sibling donors was associated with a trend toward increased mean plasma interleukin-10 concentrations (5.6 v 7.1 pg/mL; P = .06).

Conclusion

A novel two-pronged strategy of atorvastatin administration in both donors and recipients of matched sibling allogeneic HCT seems to be a feasible, safe, and potentially effective strategy to prevent acute GVHD.

INTRODUCTION

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT).1 It develops in 30% to 50% of patients receiving HLA-matched transplants from a related donor.2,3 Acute GVHD is initiated when donor T cells encounter recipient antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and become activated.4 This process requires costimulation via CD80 and CD86, which are upregulated on APCs during the early phase of acute GVHD. Activation is enhanced by local tissue damage resulting from the conditioning regimens. Local proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ), promote T-helper 1 (TH-1) differentiation of donor T cells and enhance their proliferation and reactivity against host antigens.5 In both murine models and humans, cytokine release related to the TH-1 phenotype predicts the incidence and severity of acute GVHD, whereas patients with high IL-10 production have lower risk for GVHD.6–8 Current prophylactic strategies for acute GVHD have modest efficacy and often compromise donor T cell–mediated graft-versus-tumor effects and delay immune reconstitution.9 Novel strategies to effectively prevent acute GVHD without increased risk of infectious complications and disease relapse are urgently needed.

3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-CoA reductase inhibitors (commonly known as statins) possess potent immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties that are relevant in the context of acute GVHD.10 Statin-mediated depletion of isoprenoid intermediates induces T-helper 2 (TH-2) cytokine bias and inhibition of proinflammatory TH-1 differentiation.11 Acute GVHD is thought to be mediated by alloreactive T cells with a TH-1 cytokine phenotype. Interestingly, polarized type 2 alloreactive donor T cells fail to induce experimental acute GVHD.12–14 Statins also indirectly decrease T-cell activation by reducing expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and costimulatory molecules on APCs.15,16 APCs are critical for the pathogenesis of GVHD, and strategies to prevent activation of APCs can potentially abrogate GVHD.4 Statin-mediated changes in intracellular signaling can also promote development of regulatory T cells.17 Expansion of regulatory T cells is an attractive strategy to prevent acute GVHD.18 In murine models, simultaneous atorvastatin administration in both donor and recipient mice has shown synergistic protective effects against acute GVHD (compared with administration in donors or recipients alone) by inhibiting donor T-cell proliferation, inducing donor TH-2 polarization, and downregulating MHC-II and costimulatory molecule expression on recipient APCs.19 Limited retrospective studies also suggest a protective effect of statins against acute GVHD in the clinic.20–22 On the basis of these preliminary data, we hypothesized that atorvastatin administration in both donors and recipients of matched sibling alloHCT would be a safe and effective method of preventing acute GVHD.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This prospective clinical trial was approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained before donor and patient enrollment.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients with hematologic malignancies with a consenting HLA-matched adult (age ≥ 18 years) sibling donor were eligible. Single-antigen HLA mismatch was allowed. Donors and patients with active and uncontrolled infections; abnormal renal (creatinine clearance < 40 mL/min), hepatic (serum bilirubin > 2 mg/dL; serum AST and ALT > 3× upper limit of normal), pulmonary (for patients only; diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide or forced expiratory volume in 1 second < 40% of predicted), or cardiac (left ventricular ejection fraction < 40%) function; poor Karnofsky performance score (< 60 for donors; < 70 for patients); and history of atorvastatin intolerance or allergy were excluded. Patients undergoing ex vivo or in vivo T cell–depleted alloHCT were not eligible.

Treatment and GVHD Prophylaxis

As acute GVHD prophylaxis, atorvastatin 40 mg per day orally was administered to sibling donors, starting 14 to 28 days before the anticipated first day of stem-cell collection and continuing until day 1 of leukapheresis. This 2-week window ensured that all donors received prophylaxis for at least 14 days, while simultaneously allowing longer prophylaxis where donor/patient transplantation scheduling permitted. Donor stem cells were mobilized with filgrastim (10 μg/kg per day) alone and infused fresh without cryopreservation. All patients received uniform GVHD prophylaxis with tacrolimus (0.015 mg/kg intravenously or 0.03 mg/kg per day orally, starting on day −2), methotrexate (5 mg/m2 on days +1, +3, +6, and +11), and atorvastatin (40 mg per day orally, starting on day −14). Atorvastatin was continued until all immunosuppression was stopped or until day +180, development of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD, or severe chronic GVHD (whichever occurred first). Dose of tacrolimus was adjusted to a target trough level of 5 to 12 ng/mL. Tacrolimus taper commenced after day +100, with the goal of stopping immunosuppression by day +180 in the absence of GVHD. Intensity of transplantation conditioning regimen was at the discretion of the treating physician. Growth factors to promote neutrophil recovery post-transplantation were not routinely administered. All patients received antifungal (fluconazole), antiviral (acyclovir or valacyclovir), and Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis.

End Points

Primary end points were donor/patient safety and cumulative incidence of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD at day +100. Secondary end points included cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, disease relapse, nonrelapse mortality (NRM; ie, death not preceded by disease relapse), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). All suspected cases of acute GVHD were histologically confirmed. Consensus Conference Criteria23 and National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project Criteria24 were used for grading acute and chronic GVHD, respectively. Compliance with atorvastatin prophylaxis was monitored by reviewing donor and patient diaries and assessing the remaining quantity of study medication among donors and patients. National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0) were used to analyze safety.

Immune Reconstitution, Donor-Cell Chimerism, and Cytokine Assays

For immune reconstitution assays, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from EDTA-anticoagulated whole-blood samples obtained on days +30, +100, +180, and +365 post-transplantation (described in detail in Data Supplement). In this analysis, CD4+ T cells were defined as CD3+CD4+, CD8+ T cells as CD3+CD8+, CD4+ memory T cells as CD3+CD27+CD45RO+CD4+, CD8+ memory T cells as CD3+CD27+ CD45RO+CD8+, CD4+ naive T cells as CD3+CD45RA+CD45RO− CD4+, CD8+ naive T cells as CD3+CD45RA+CD45RO−CD8+, natural killer (NK) cells as CD3−CD56+CD16+, and B cells as CD19+. We determined the effects of atorvastatin on donor plasma cytokine profiles by analyzing baseline and postatorvastatin administration donor plasma samples (described in detail in Data Supplement). Lineage-specific donor-cell chimerism analysis was performed on days +30, +100, +180, and +360 post-transplantation. Complete donor chimerism was defined as presence of ≥ 95% of donor cells.

Statistical Considerations

This phase II study used a minimax Simon two-stage design to test the null hypothesis H0: P ≥ .35 versus the alternate H1: P ≤ .15, where P is probability of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD at day +100 (described in detail in Data Supplement). Time of neutrophil engraftment was considered the first of 3 successive days with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 500/μL after post-transplantation nadir. Time of platelet engraftment was considered the first of 3 consecutive days with platelet count ≥ 20,000/μL, in the absence of platelet transfusions. OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. OS was defined as time from transplantation to death resulting from any cause, and surviving patients were censored at last follow-up. PFS from transplantation was calculated using death and disease relapse/progression as events. Cumulative incidences of NRM and relapse risk were estimated by considering these two events as competing risks.25 Cumulative incidence of acute GVHD or chronic GVHD was estimated with relapse and death without GVHD as competing risks.25 Comparisons were made of donor serum cytokine profiles between pre– and post–atorvastatin administration samples using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. All P values are two sided. Statistical analyses were performed using SPLUS statistical software (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA) and R statistical software (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Study Cohort

From September 2010 through October 2012, 30 donor/patient pairs were enrolled. Baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. Median donor and patient age was 52.5 years (range, 24 to 75 years) and 54.5 years (range, 22 to 72 years), respectively. Seven donors and five patients were using a statin drug at baseline, which was discontinued at the initiation of atorvastatin. Median duration of apheresis was 1 day, with no apparent impairment of stem-cell collection yields noted with donor atorvastatin prophylaxis (Table 1). Eleven patients (36.6%) had chemorefractory disease at transplantation, and 13 patients (43.3%) received myeloablative conditioning (MAC). Ten allografts were ABO mismatched, and nine were from a multiparous female donor to a male recipient. Median follow-up of survivors was 12 months (range, 4 to 29 months).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient, Sibling Donor, and Allograft Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 30) | ||

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 54.5 | |

| Range | 22-72 | |

| Male sex | 20 | 66.6 |

| Karnofsky performance score | ||

| Median | 90 | |

| Range | 70-100 | |

| HCT-CI | ||

| Median | 1.5 | |

| Range | 0-5 | |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 9 | 30 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 8 | 26.6 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 3 | 10 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 3 | 10 |

| Primary myelofibrosis | 2 | 6.6 |

| Others | 5 | 16.6 |

| ASBMT risk category* | ||

| Low | 8 | 26.6 |

| Intermediate | 10 | 33.3 |

| High | 10 | 33.3 |

| Other | 2 | 6.6 |

| Prior autologous transplantation | 5 | 16.6 |

| Myeloablative conditioning | ||

| Busulfan/cyclophosphamide | 2 | 6.6 |

| Fludarabine/busulfan | 11 | 36.6 |

| Reduced-intensity conditioning | ||

| Fludarabine/busulfan | 17 | 56.6 |

| Chemotherapy-refractory disease | 11 | 36.6 |

| Statin use at time of enrollment | 5 | 16.6 |

| Donors (n = 30) | ||

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 52.5 | |

| Range | 24-75 | |

| Male sex | 17 | 56.6 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | ||

| Baseline | 100.5 | |

| Normal range < 223 | 35-981 | |

| Statin use at time of enrollment | 7 | 23.3 |

| Allograft | ||

| Peripheral blood graft† | 30 | 100 |

| 8/8 allele-level match‡ | 30 | |

| ABO-mismatched transplantation | 10 | 33.3 |

| Female donor to male recipient | 9 | 30 |

| EBV-seropositive donor and/or recipient | 30 | 100 |

| CMV-seropositive donor and/or recipient | 24 | 80 |

| No. of apheresis sessions | ||

| Median | 1 | |

| Range | 1-2 | |

| No. of donors requiring 2 days of apheresis | 3 | 10 |

| Collection of CD34+ cells per recipient body weight (kg), × 106 | ||

| Median | 4.5 | |

| Range | 1.3-16.1 | |

| Infused CD34+ cells per recipient body weight (kg), × 106 | ||

| Median | 4.25 | |

| Range | 1.3-13.6 | |

| Infused CD3+ cells per recipient body weight (kg), × 107 | ||

| Median | 33.05 | |

| Range | 16.4-74.8 | |

Abbreviations: ASBMT, American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index.

Disease-risk classification based on standard ASBMT criteria.26

One patient received combined peripheral blood and bone marrow allograft because of poor mobilization.

High-resolution typing at HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1.

Engraftment and Chimerism

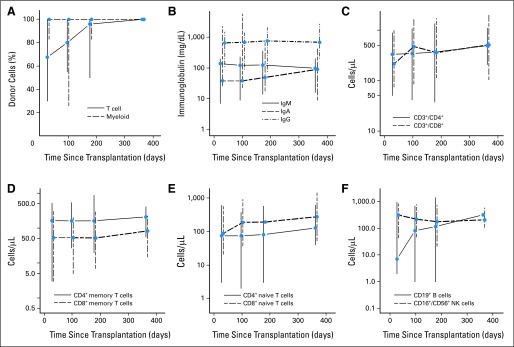

There were no primary graft failures. Median time to neutrophil and platelet engraftment in patients receiving MAC was 16 days (range, 13 to 19 days) and 15 days (range, 11 to 22 days), respectively. Two patients experienced secondary graft failure (ANC < 500/μL after initial neutrophil engraftment), which promptly responded to growth factors. Median percentage of donor myeloid-cell chimerism was 100% at days +30, +100, +180, and +365, whereas median donor T-cell chimerism was complete from day +180 onward (Fig 1A; Data Supplement).

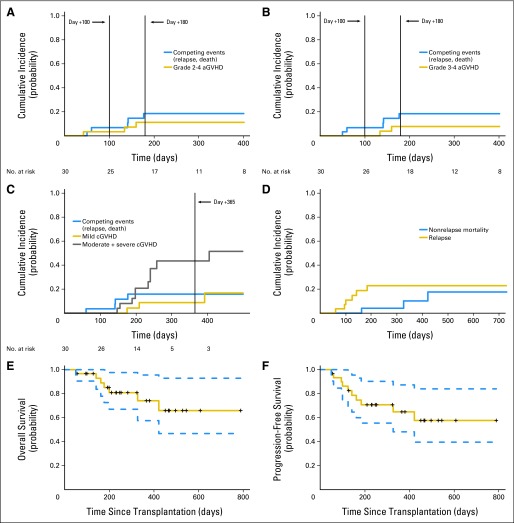

Fig 1.

Kinetics of donor-cell chimerism and immune reconstitution post-transplantation. Median (A) donor myeloid and T-cell chimerism and (B) immunoglobulin A (IgA), G, and M levels (in mg/dL) post-transplantation. (C) CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell, (D) CD4+ and CD8+ memory T-cell, (E) CD4+ and CD8+ naive T-cell, and (F) CD19+ B-cell and natural killer (NK) –cell reconstitutions. Median cell counts with vertical bars indicating interquartile ranges.

GVHD

All patients were evaluable for acute GVHD. Two patients (one each undergoing reduced-intensity conditioning [RIC] and MAC) developed grade 1 acute GVHD (at days +29 and +52, respectively), which was managed with topical corticosteroids alone. Median time to onset of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD was 134 days (range, 42 to 160 days). Among the three patients developing grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD, two received MAC. Cumulative incidence rates of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD at days +100 and +180 were 3.3% (95% CI, 0.2% to 14.8%) and 11.1% (95% CI, 2.7% to 26.4%), respectively (Fig 2A). The respective figures for grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD were 0% and 7.8% (95% CI, 1.3% to 22.3%; Fig 2B). Among the two patients with grade 3 to 4 acute GVHD (MAC, n = 1; RIC, n = 1), one patient developed grade 4 GVHD on day +134 after discontinuing immunosuppression on day +106 at the discretion of the treating physician because of high risk of disease relapse (FLT3-ITD–positive acute myeloid leukemia in second complete remission after two rounds of reinduction). Chronic GVHD occurred in 13 patients, with a median time to onset of 209 days (range, 147 to 405 days; Table 2). Four patients with chronic GVHD previously had grade 1 to 4 acute GVHD. Two such patients had features of active acute GVHD at the onset of chronic GVHD (ie, overlap syndrome). Nine patients had de novo chronic GVHD. Cumulative incidence rates of mild and moderate/severe chronic GVHD at 1 year were 8.8% (95% CI, 1.4% to 25%) and 43.5% (95% CI, 20.7% to 64.4%), respectively (Fig 2C). In five patients with severe chronic GVHD, organ involvement included eyes (n = 3), mouth (n = 3), skin (n = 2), gut (n = 1), and lungs (n = 3). Three patients with grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD and 10 patients with moderate or severe chronic GVHD received systemic immunosuppression.

Fig 2.

Atorvastatin for acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) prophylaxis. Cumulative incidence of (A) grade 2 to 4 aGVHD, (B) grade 3 to 4 aGVHD, and (C) mild and moderate plus severe chronic GVHD (cGVHD) with relapse/progression and death as competing events and (D) nonrelapse mortality and disease relapse. (E) Overall and (F) progression-free survival curves; dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

Table 2.

Distribution of Chronic GVHD by Severity

| Organ Involved | No. |

|---|---|

| Mild (n = 3) | |

| Eyes | 2 |

| Mouth | 1 |

| Skin | 1 |

| Moderate (n = 5) | |

| Eyes | 3 |

| Mouth | 3 |

| Skin | 3 |

| Liver | 4 |

| GI tract | 3 |

| Severe (n = 5) | |

| Eyes | 3 |

| Mouth | 3 |

| Skin | 1 |

| GI tract | 1 |

| Lung | 3 |

Abbreviation: GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

Immune Reconstitution and Donor Cytokine Profiles

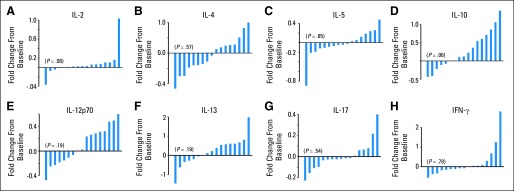

Patient immune reconstitution data are shown in Figures 1B to 1F and in the Data Supplement. Median immunoglobulin G levels were within normal limits at all tested time points (days +30, +100, +180, and +365). Reconstitution of the T-cell compartment was prompt. Median CD8+ T-cell and CD8+ naive T-cell counts at all tested time points and median CD4+ T-cell counts from day +100 onward were within normal limits. Median CD19+ B-cell and CD16+/CD56+ NK-cell counts at the 1-year mark were 317/μL and 204/μL, respectively. Figure 3 depicts effect of atorvastatin administration on donor plasma cytokine concentrations. No statistically significant changes were seen in donor IL-17 or TH-1 cytokine concentrations (IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-12p70) after atorvastatin administration. A trend toward higher mean IL-10 concentrations after atorvastatin administration was seen (5.6 v 7.1 pg/mL; P = .06). This trend persisted after excluding six donors who were taking a statin drug at baseline (4.8 v 7.1 pg/mL; P = .05; data on other cytokines are summarized in Data Supplement).

Fig 3.

Effect of atorvastatin administration on sibling donor plasma cytokine profiles. To evaluate effects of atorvastatin administration on donor cytokine profiles, baseline specimens were collected from sibling donors before starting atorvastatin, and post–atorvastatin administration samples were collected immediately before first dose of filgrastim for stem-cell mobilization (n = 17). Waterfall plots of eight cytokines analyzed depict fold changes (ie, fold increase or decrease) in donor plasma cytokine levels after 2- to 4-week course of atorvastatin administration compared with baseline values: (A) interleukin-2 (IL-2), (B) IL-4, (C) IL-5, (D) IL-10, (E) IL-12p70, (F) IL-13, (G) IL-17, and (H) interferon gamma (IFN-γ).

Compliance and Toxicity

Donors received atorvastatin for a median of 14 days (range, 7 to 24 days). Eleven donors received prophylaxis for more than 14 days. Drug compliance was good, with three donors missing a single dose each, whereas one donor missed seven doses (recipient of this donor coincidently developed grade 4 acute GVHD). Patients received atorvastatin for a median of 192 days (range, 60 to 199 days). Atorvastatin was held in three patients for one episode each of severe mucositis (2 days), iron overload–related liver function abnormalities (5 days), and potential atorvastatin-related liver function abnormalities (6 days). In all patients, atorvastatin was reintroduced without additional events. Adverse events potentially related to atorvastatin are listed in Table 3. No grade 3 to 4 toxicities were observed in donors or patients.

Table 3.

Adverse Events* in Donors and Patients

| Toxicity | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 to 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donors | |||

| Ankle edema | 1 | — | — |

| Fatigue | 1 | — | — |

| Myalgias | 2 | 1 | — |

| LFT elevations | 1 | — | — |

| Palpitations | 1 | — | — |

| Patients | |||

| LFT elevations | 1 | — | — |

Abbreviation: LFT, liver function test.

Possibly, probably, or definitely related to atorvastatin.

Infection, Relapse, and Survival

Infectious complications were infrequent. Three patients (10%) each developed cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation and BK-viral hemorrhagic cystitis. There were no Epstein-Barr virus reactivations or CMV, adenoviral, or invasive fungal infections. Bacterial infections in the first 180 days were manageable and included Clostridium difficile diarrhea (n = 3), Staphylococcus aureus abscess (n = 1), Gram-positive bacteremia (n = 3), Gram-negative bacteremia (n = 1), and pneumonia (n = 2). Cumulative incidence of NRM at day +100 and 1 year was 0% and 9.8% (95% CI, 1.4% to 28%), respectively (Fig 2D). At 1 year, cumulative incidence of relapse was 25.4% (95% CI, 10.9% to 42.9%; Fig 2D). One-year OS and PFS were 74% (95% CI, 58% to 96%) and 65% (95% CI, 48% to 87%), respectively (Figs 2E and 2F). Causes of death are summarized in the Data Supplement.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated a novel two-pronged strategy of immune modulation in donor/recipient pairs of matched sibling allogeneic HCT with atorvastatin (plus standard GVHD prophylaxis in transplant recipients) as GVHD prophylaxis and report a low incidence of early- (before day +100) and late-onset (after day +100) acute GVHD. This strategy was feasible, with excellent donor and recipient compliance, and was not associated with serious toxicities, increased infectious complications, or higher-than-expected rates of relapse. A statistically nonsignificant trend toward increased donor IL-10 levels after atorvastatin administration was also observed.

Rates of grade 2 to 4 and stage III to IV acute GVHD at day +100 in our study were low (3.3% and 0%, respectively). Expected rates of acute GVHD for matched sibling HCT with standard calcineurin inhibitor/methotrexate-based prophylaxis in prior studies have ranged from 30% to 50%.2,3,27 At our institution, among patients undergoing matched sibling HCT and receiving calcineurin inhibitor–based GVHD prophylaxis (± antithymocyte globulin), rates of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD at day +100 have ranged from 30% to 35%.28 Acute GVHD rates in our study are especially encouraging because this study included patients potentially at higher risk of developing acute GVHD, including those undergoing MAC (43.3%),2 those with high-risk (33.3%) or chemorefractory disease (36.6%),2 and those receiving ABO-mismatched (33.3%)29 or female donor–to–male recipient (30%) allografts.2 Reporting acute GVHD rates only through day +100 could potentially result in underestimation of the true incidence of acute GVHD, especially in the setting of RIC HCT, supporting the recent efforts to describe incidence of late-onset classic acute GVHD.9,30 In our study, day +180 rates of grade 2 to 4 (11.1%) and stage III to IV (7.8%) acute GVHD were reassuring. The efficacy of atorvastatin in preventing acute GVHD seen in our study merits confirmatory investigation in a prospective, randomized trial. Despite low cumulative incidence of acute GVHD, rates of chronic GVHD in our study remain comparable to those in prior studies of tacrolimus/methotrexate prophylaxis.3 Interestingly, all except two cases of chronic GVHD in our study were seen after stopping atorvastatin beyond day +180. Onset of chronic GVHD mostly after discontinuing atorvastatin, combined with limited prior data suggesting protective effects of statins against chronic GVHD,21,31 warrants investigation of the role of longer atorvastatin prophylaxis in mitigating risk of chronic GVHD.

The trend toward increased donor IL-10 plasma concentrations with atorvastatin administration seen in our study is intriguing. The small number of paired samples available (n = 17) could have potentially limited our ability to detect a statistically significant difference. Interestingly, atorvastatin-mediated increase in IL-10 concentrations was previously documented in murine models11 and has been replicated in several randomized32,33 and single-arm studies34 in humans using clinically relevant doses (of up to 40 mg per day). Increased IL-10 concentrations with atorvastatin administration in donor mice were also seen in murine GVHD models.19 IL-10 downregulates immune response and can facilitate the induction of tolerance after alloHCT35 by suppressing production of TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and IFN-γ. IL-10 downregulates the expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules and through these mechanisms may attenuate alloreactive T-cell responses.36 IL-10 has also been shown to enhance the generation of regulatory T cells that mediate anergy and facilitate tolerance.37 In fact, polymorphisms in sibling donor IL-10 gene promoter region6 and recipient IL-10 receptor β gene7 as well as increased patient IL-10 concentrations8 are associated with reduced risk of acute GVHD after matched sibling transplantation. It is possible that atorvastatin-induced higher donor IL-10 concentrations seen in our study were partially mitigating the risk of acute GVHD after alloHCT. These observations, of course, require further validation. Moreover, bearing in mind the multiple comparisons in evaluating donor-serum cytokine concentrations, the changes in IL-10 concentrations should be interpreted cautiously and considered mainly as hypothesis generating.

Atorvastatin has a proven safety track record. Comprehensive assessment of the atorvastatin safety profile using data from 44 clinical trials comprising 16,495 patients demonstrated that the incidence of adverse events with atorvastatin did not increase in the 10- to 80-mg dose range and was similar to that observed with placebo.38 Consistent with published data, atorvastatin administration to sibling donors and patients in our study was feasible and safe, and no serious adverse events were seen. Although some,21 but not all,20,22 retrospective studies have suggested an increased risk of disease relapse with statin use, the 1-year relapse rate of 25.4% in this study is reassuring, especially considering the fact that 36.6% of patients in our study had active, refractory disease at baseline. The low NRM and infrequent infectious complications in our study are noteworthy. More-intense (and often expensive) GVHD prophylactic strategies employing ex vivo T-cell depletion or monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies display a narrow therapeutic index and are frequently complicated by increased risk of infectious complications and relapse,39,40 adding significant burden to the already enormous health care costs of transplant recipients.41 Validation of our study results could potentially lead to a more cost-effective and nontoxic strategy for the prevention of acute GVHD after matched sibling alloHCT.

In summary, a novel two-pronged strategy of atorvastatin administration to both donors and recipients of matched sibling allogeneic HCT seems to be a feasible, safe, and potentially effective strategy to prevent acute GVHD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Marcos de Lima, MD (Case Western Reserve University), and Steven M. Devine, MD (The Ohio State University), for their helpful comments on the manuscript; Leah Darr and MBRCC Clinical Trials Research Unit for regulatory support; and our patients, donors, bone marrow transplantation nurses, and midlevel providers.

Glossary Terms

- Cytokines:

Cell communication molecules that are secreted in response to external stimuli.

- HLA (human leukocyte antigen):

The human major histocompatibility complex, which is expressed as two sets of highly polymorphic cell surface molecules, termed HLA class I and HLA class II. HLA class I molecules are expressed on all nucleated cells and are encoded by diverse alleles of the HLA-A, HLA-B, or HLA-C genes (eg, HLA-A1 [HLA molecule encoded by the A1 allele of the HLA-A gene] and HLA-B7 [HLA molecule encoded by the B7 allele of the HLA-B gene]). HLA class I molecules bind peptides derived from cellular proteins upon processing. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes, expressing the CD8 coreceptor, recognize cell-bound peptides in association with HLA class I molecules on target cells.

- T-helper 2:

CD4 T cells that secrete cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-6. These cells support the proliferation of B cells and dampen the function of cytotoxic CD8 T cells.

Footnotes

See accompanying article on page 4462

Supported in part by research funding from American Cancer Society Grant No. 116837-IRG-09-061-01 (M.H.), Conquer Cancer Foundation of American Society of Clinical Oncology Career Development Award (M.H.), and American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation New Investigator Award (M.H.). Correlative studies were performed in the West Virginia University biospecimen processing and flow cytometry cores, supported in part by National Institutes of Health NIGMS P30 GM103488 (to L.F.G).

Terms in blue are defined in the glossary, found at the end of this article and online at www.jco.org.

Presented in part at the 54th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Atlanta, GA, December 8-11, 2012, and American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation Annual Tandem Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT, February 13-17, 2013.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information: NCT01175148.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: William Tse, TEVA Pharmaceuticals Industries (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Mehdi Hamadani, Celgene, Otsuka Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Patents: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Mehdi Hamadani, Laura F. Gibson, Scot C. Remick, William Petros, Michael D. Craig

Collection and assembly of data: Mehdi Hamadani, Kathleen M. Brundage, Jeffrey A. Vos, Pamela Bunner

Data analysis and interpretation: Mehdi Hamadani, Laura F. Gibson, Sijin Wen, William Tse, Aaron Cumpston, Michael D. Craig

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Deeg HJ. How I treat refractory acute GVHD. Blood. 2007;109:4119–4126. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-041889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagasia M, Arora M, Flowers ME, et al. Risk factors for acute GVHD and survival after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:296–307. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-364265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratanatharathorn V, Nash RA, Przepiorka D, et al. Phase III study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus (prograf, FK506) with methotrexate and cyclosporine for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1998;92:2303–2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shlomchik WD, Couzens MS, Tang CB, et al. Prevention of graft versus host disease by inactivation of host antigen-presenting cells. Science. 1999;285:412–415. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara JL, Deeg HJ. Graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:667–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103073241005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin MT, Storer B, Martin PJ, et al. Relation of an interleukin-10 promoter polymorphism to graft- versus-host disease and survival after hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2201–2210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin MT, Storer B, Martin PJ, et al. Genetic variation in the IL-10 pathway modulates severity of acute graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic cell transplantation: Synergism between IL-10 genotype of patient and IL-10 receptor beta genotype of donor. Blood. 2005;106:3995–4001. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holler E, Roncarolo MG, Hintermeier-Knabe R, et al. Prognostic significance of increased IL-10 production in patients prior to allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:237–241. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reshef R, Luger SM, Hexner EO, et al. Blockade of lymphocyte chemotaxis in visceral graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:135–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broady R, Levings MK. Graft-versus-host disease: Suppression by statins. Nat Med. 2008;14:1155–1156. doi: 10.1038/nm1108-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youssef S, Stuve O, Patarroyo JC, et al. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, promotes a Th2 bias and reverses paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease. Nature. 2002;420:78–84. doi: 10.1038/nature01158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler DH, Kurasawa K, Husebekk A, et al. Cells of Th2 cytokine phenotype prevent LPS-induced lethality during murine graft-versus-host reaction: Regulation of cytokines and CD8+ lymphoid engraftment. J Immunol. 1994;152:1004–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foley JE, Mariotti J, Ryan K, et al. Th2 cell therapy of established acute graft-versus-host disease requires IL-4 and IL-10 and is abrogated by IL-2 or host-type antigen-presenting cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:959–972. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krenger W, Snyder KM, Byon JC, et al. Polarized type 2 alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ donor T cells fail to induce experimental acute graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 1995;155:585–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Liebig T, von Bergwelt-Baildon M. Statins inhibit human APC function: Implications for the treatment of GVHD. Blood. 2008;112:1544–1545. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS. Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: From protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:358–370. doi: 10.1038/nri1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mausner-Fainberg K, Luboshits G, Mor A, et al. The effect of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T cells. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:829–839. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edinger M, Hoffmann P, Ermann J, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeiser R, Youssef S, Baker J, et al. Preemptive HMG-CoA reductase inhibition provides graft-versus-host disease protection by th-2 polarization while sparing graft-versus-leukemia activity. Blood. 2007;110:4588–4598. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamadani M, Awan FT, Devine SM. The impact of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition on the incidence and severity of graft-versus-host disease in patients with acute leukemia undergoing allogeneic transplantation. Blood. 2008;111:3901–3902. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotta M, Storer BE, Storb R, et al. Impact of recipient statin treatment on graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1463–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotta M, Storer BE, Storb RF, et al. Donor statin treatment protects against severe acute graft-versus-host disease after related allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:1288–1295. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, et al. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: New representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Standard criteria. http://www.asbmt.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=35.

- 27.Pidala J, Kim J, Jim H, et al. A randomized phase II study to evaluate tacrolimus in combination with sirolimus or methotrexate after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2012;97:1882–1889. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.067140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamadani M, Craig M, Phillips GS, et al. Higher busulfan dose intensity does not improve outcomes of patients undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation following fludarabine, busulfan-based reduced toxicity conditioning. Hematol Oncol. 2011;29:202–210. doi: 10.1002/hon.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seebach JD, Stussi G, Passweg JR, et al. ABO blood group barrier in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation revisited. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:1006–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koreth J, Stevenson KE, Kim HT, et al. Bortezomib-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in HLA-mismatched unrelated donor transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3202–3208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hori A, Kanda Y, Goyama S, et al. A prospective trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of pravastatin for the treatment of refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2005;79:372–374. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000151001.64189.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li JJ, Fang CH. Effects of 4 weeks of atorvastatin administration on the antiinflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 in patients with unstable angina. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1735–1738. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.049700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez C, Francisco G, Ciudin A, et al. Effect of atorvastatin on lipoprotein (a) and interleukin-10: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Jiang H, Liu W, et al. Effects of fluvastatin therapy on serum interleukin-18 and interleukin-10 levels in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Acta Cardiol. 2010;65:285–289. doi: 10.2143/AC.65.3.2050343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tseng LH, Storer B, Petersdorf E, et al. IL10 and IL10 receptor gene variation and outcomes after unrelated and related hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87:704–710. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318195c474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding L, Linsley PS, Huang LY, et al. IL-10 inhibits macrophage costimulatory activity by selectively inhibiting the up-regulation of B7 expression. J Immunol. 1993;151:1224–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levings MK, Sangregorio R, Galbiati F, et al. IFN-alpha and IL-10 induce the differentiation of human type 1 T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5530–5539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newman CB, Palmer G, Silbershatz H, et al. Safety of atorvastatin derived from analysis of 44 completed trials in 9,416 patients. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:670–676. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00820-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner JE, Thompson JS, Carter SL, et al. Effect of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis on 3-year disease-free survival in recipients of unrelated donor bone marrow (T-cell depletion trial): A multi-centre, randomised phase II-III trial. Lancet. 2005;366:733–741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66996-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bacigalupo A, Lamparelli T, Bruzzi P, et al. Antithymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in transplants from unrelated donors: 2 randomized studies from Gruppo Italiano Trapianti Midollo Osseo (GITMO) Blood. 2001;98:2942–2947. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SJ, Klar N, Weeks JC, et al. Predicting costs of stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:64–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.