Background: The physiological significance of C5-epimerization of glucuronic acid (GlcA) remains elusive.

Results: Drosophila Hsepi mutants are viable and fertile with only minor morphological defects, but they have a short lifespan.

Conclusion: Sulfation compensation and 2-O-sulfated GlcA contribute to the mild phenotypes of Hsepi mutants.

Significance: The findings suggest novel developmental roles of 2-O-sulfated GlcA.

Keywords: Drosophila, Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), Genetics, Heparan Sulfate, Immunohistochemistry, C5-Epimerase, Gagosome, Sulfation Compensation

Abstract

During the biosynthesis of heparan sulfate (HS), glucuronyl C5-epimerase (Hsepi) catalyzes C5-epimerization of glucuronic acid (GlcA), converting it to iduronic acid (IdoA). Because HS 2-O-sulfotransferase (Hs2st) shows a strong substrate preference for IdoA over GlcA, C5-epimerization is required for normal HS sulfation. However, the physiological significance of C5-epimerization remains elusive. To understand the role of Hsepi in development, we isolated Drosophila Hsepi mutants. Homozygous mutants are viable and fertile with only minor morphological defects, including the formation of an ectopic crossvein in the wing, but they have a short lifespan. We propose that two mechanisms contribute to the mild phenotypes of Hsepi mutants: HS sulfation compensation and possible developmental roles of 2-O-sulfated GlcA (GlcA2S). HS disaccharide analysis showed that loss of Hsepi resulted in a significant impairment of 2-O-sulfation and induced compensatory increases in N- and 6-O-sulfation. Simultaneous block of Hsepi and HS 6-O-sulfotransferase (Hs6st) activity disrupted tracheoblast formation, a well established FGF-dependent process. This result suggests that the increase in 6-O-sulfation in Hsepi mutants is critical for the rescue of FGF signaling. We also found that the ectopic crossvein phenotype can be induced by expression of a mutant form of Hs2st with a strong substrate preference for GlcA-containing units, suggesting that this phenotype is associated with abnormal GlcA 2-O-sulfation. Finally, we show that Hsepi formed a complex with Hs2st and Hs6st in S2 cells, raising the possibility that this complex formation contributes to the close functional relationships between these enzymes.

Introduction

HSPGs2 play critical roles in a wide range of biological processes by regulating the action of growth factors, such as FGF, Wnt, TGF-β, and Hedgehog (1, 2). They are composed of a core protein and a long, negatively charged linear polysaccharide, heparan sulfate (HS). HS biosynthesis is a complex, multistep process. HS chains are polymerized by EXT proteins as unbranched, repeating disaccharides composed of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and glucuronic acid (GlcA). During chain polymerization, N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase (NDST) removes the acetyl groups from some of the GlcNAc residues and replaces them with sulfate groups. After N-sulfation, glucuronyl C5-epimerase (Hsepi) converts GlcA to iduronic acid (IdoA) followed by O-sulfation events at specific ring positions. Because only a fraction of the potential targets are modified at each modification step, the resultant HS chain has considerable structural heterogeneity.

The biosynthesis of HS is controlled by a feedback mechanism known as “HS sulfation compensation,” which was first recognized in the Hs2st mouse null mutant model (3). HS purified from Hs2st−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts did not have 2-O-sulfate groups, but this loss was compensated by increased N- and 6-O-sulfation. Similarly, Drosophila Hs2st and Hs6st mutations induce compensatory increases in sulfation at 6-O and 2-O positions, respectively, restoring a wild-type net charge on HS in both genotypes (4). This compensation rescues FGF, Wingless, and BMP signaling pathways in vivo, thus ensuring the robustness of developmental systems (4, 5). However, the mechanism by which cells sense the lack of a specific sulfation event and induce a compensatory reaction is unknown.

The fact that a change in sulfation status at one ring position is responded to by a compensatory sulfation at other positions indicates that activities of multiple HS-modifying enzymes are tightly regulated. From this point of view, it is important to understand physical interactions between HS biosynthetic/modifying enzymes. It has been proposed that these enzymes form a physical complex called a “gagosome” to coordinate HS synthesis (1, 6, 7). Previous studies have identified a physical association between Hsepi and Hs2st (6) and between NDST1 and EXT2 (8), supporting the gagosome model. What other components participate in the gagosome and how this complex regulates HS structures still remain elusive.

One of the least understood steps of HS biosynthesis is C5-epimerization of GlcA to IdoA catalyzed by Hsepi. Sulfation at the 2-O position of uronic acid occurs almost exclusively on IdoA residues and very rarely on GlcA (1, 9). For this reason, C5-epimerization of GlcA to IdoA is required for normal sulfation patterns and biological processes. It has been shown that genetic loss of Hsepi results in a wide array of developmental defects and lethality in several animal models, including mouse, zebrafish, and Caenorhabditis elegans (10–14). The disruption of the Hsepi gene largely phenocopied that of Hs2st in many of these models, consistent with the fact that 2-O-sulfation is dependent on C5-epimerization. Hsepi−/− mice die shortly after birth with renal agenesis, lung defects, and skeletal malformations (10). HS from the Hsepi−/− mutants was devoid of IdoA but showed increased N- and 6-O-sulfation. Kidney agenesis and skeletal abnormalities were also commonly observed in Hs2st-deficient mice, whereas the Hs2st−/− mice have normal lungs and survive a little longer than Hsepi mutants (15). In addition, Hs2st-deficient mice show mild reductions in the thickness of the cerebral cortex and the spinal cord in the brain (16). On the other hand, Hsepi-deficient mice did not show any defect in other organ systems, such as the brain and vasculature. Because normal development of these organs requires HS-dependent signaling pathways (17), the up-regulation of N- and 6-O-sulfation may rescue some signaling pathways. In fact, HS from the Hsepi−/− cells showed aberrant interactions with FGF2 and glia-derived neurotropic factor but interacted normally with FGF10 (18). However, the mechanism for the differential effects of Hs2st and Hsepi mutations on morphogenesis is not understood.

Despite the strong preference of Hs2st on the C2 position of IdoA over GlcA, it can add 2-O-sulfate groups to GlcA (19). The product of such reaction, GlcA2S, is found on only 1% of total disaccharide units in most naturally occurring HS. However, higher levels of GlcA2S were found in cerebral cortex (20). This suggested that GlcA2S may be biologically important, but its functional significance is unknown.

Here we demonstrate that Drosophila Hsepi mutants show only modest morphological defects, whereas they have a significantly shorter longevity than wild type. Hsepi mutation resulted in a significant reduction of 2-O-sulfation and induced increases in N- and 6-O-sulfation. The up-regulation of 6-O-sulfation was required for the rescue of tracheoblast formation. On the other hand, Hsepi appears to play a limited role in HS compensation in Hs2st mutants: biochemically, the lack of Hsepi reduced the level of compensatory increases in N- and 6-O-sulfation, but the difference was not detectable in phenotypic analyses. Based on similarities and differences of phenotypic and biochemical analyses of Hs2st, Hsepi, and Hs2st Hsepi double mutants as well as phenotypes induced by mutant forms of Hs2st, we discuss the roles of 2-O-sulfated GlcA in development. We propose two mechanisms, HS sulfation compensation and developmental roles of GlcA2S, as contributing factors for the mild phenotypes of Hsepi mutants. We also show that Hsepi formed a complex with both Hs2st and Hs6st in S2 cells, consistent with intimate functional relationship between these enzymes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fly Strains

The detailed information for fly strains used is described in FlyBase. All flies were maintained at 25 °C. Oregon-R was used as a wild-type strain. The following alleles were used as null or strong hypomorphic mutants for each gene: Hs2std267, Hs6std770 (4), sulfateless03844 (sfl03844) (21), dallygem (22), sdc48 (23), dlp1 (24), and Sulf1P1 (25). Two deficiency strains, Df(2R)ED1618 (42C4-43A1) and Df(2R)cn88b (42A1-E7), which eliminate the genomic region, including the Hsepi locus, were used for P-element imprecise excision and genetic assays to characterize excision alleles. hedgehog (hh)-GAL4 and breathless (btl)-GAL4 were used to induce expression of UAS transgenes and are described in FlyBase. Other transgenic lines used were UAS-Hsepi RNAi, UAS-Hs6st RNAi, and UAS-GFP.

To generate Hsepi mutations, a P-element, P{SUPor-P}CG3194[KG02877] was excised by P-element transposase from P{ry+, Δ2–3} (99B). This excision was performed in the presence of one copy of deficiency chromosome (Df(2R)ED1618) to increase the efficiency of imprecise excision events. Imprecise excisions were screened by PCR using flanking primers to identify deletions, and the extent of each deletion was determined by sequencing PCR products that spanned the junction. To determine lethality of mutants, heterozygous mutants over a balancer were crossed to each other, and adult progenies with or without the balancer chromosome were counted. Only female adult wings were used to score adult wing phenotypes, such as chemosensory bristle formation, wing vein defect, and ectopic crossvein structures. Student's t test was used to calculate significance for phenotypic analyses, and log rank test was used for the longevity assay.

DNA Constructs and Transgenic Flies

Site-directed mutagenesis of Drosophila Hs2st was designed based on previous information on residues responsible for catalytic activity and substrate specificity of vertebrate Hs2st homologues (26, 27). Hs2st[DEAD] was constructed by introducing the mutations H139A and H141A. This construct is equivalent to H140A/H142A of vertebrate Hs2st, which showed complete loss of catalytic function (26). Hs2st[IdoA] and Hs2st[GlcA] were constructed by introducing the mutation Y93A (equivalent to Y94A of chick Hs2st) and R188A (equivalent to R189A of chick Hs2st), respectively. The chick Y94A mutant showed a substantial preference for IdoA-containing substrate over GlcA-containing substrate, whereas the chick R189A mutant showed activity exclusively with GlcA-containing substrate. Hs2st[WT] is a wild-type Hs2st construct. Hs2st[WT], Hs2st[DEAD], Hs2st[IdoA], and Hs2st[GlcA] cDNAs were cloned into UAS.attB vector (a gift from K. Basler), and transgenic strains bearing these UAS constructs were generated by BestGene Inc. using φC31-mediated integration of respective plasmid DNA into Basler ZH line 68E (28). Construction of the Golgi-tethered form of Sulf1 (Sulf1[Golgi]-HA) was described previously (25).

Quantitative PCR

Ten 1-day-old female flies were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) to isolate total RNA. The RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen) and purified with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of purified RNA with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed in duplicate on each of three independent biological replicates in the Mx3000P qPCR System (Stratagene) using EvaGreen qPCR MasterMix (MidSci). rp49 was used as a normalization control. The following primers were used: rp49 forward, 5′-ACAGGCCCAAGATCGTGAAG-3′; rp49 reverse, 5′-TGTTGTCGATACCCTTGGGC-3′; sfl forward, 5′-CACGCATTATGTCGATACGG-3′; sfl reverse, 5′-GTGTTTGCCACCAGAGTTGA-3′; Hs2st forward, 5′-TCGGAGTCACAGAGCAGATG-3′; Hs2st reverse, 5′-CCGCAGATGAGATTTGTTTG-3′; Hs6st forward, 5′-GCGCTCCAAAATCCGAACAA-3′; Hs6st reverse, 5′-CGTTTGGATAGGGCGCATAC-3′; Sulf1 forward, 5′-CCTCAGGATCCATTGCTTGT-3′; Sulf1 reverse, 5′-TCGGCTCCCCAGTATAGTCA-3′.

Immunohistochemistry and RNA in Situ Hybridization

Immunostaining was performed as described previously (29, 30). Adult ovaries and testes were dissected and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. Anti-FasIII was used to visualize ovarian somatic cells. To visualize actin filament in testes, Alexa Fluor 564-conjugated phalloidin was used. TOPRO-3 (Invitrogen) was used for nuclear counterstaining in the ovary and wing disc. Secondary antibodies were from the Alexa Fluor series (1:500; Molecular Probes).

In situ RNA hybridization was performed as described previously (25, 31). Imaginal discs were dissected from third instar larvae and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Digoxigenin-labeled Hsepi RNA probes were synthesized using a DIG RNA Labeling kit (Roche Applied Science). Anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase was used as a secondary antibody. The signal was developed by a standard protocol using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as a substrate.

Co-immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis

cDNAs for Hs2st, Hsepi, and Hs6st were cloned into pAWH and pAWM vectors. Co-immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (25, 32) using Drosophila S2 cells. Anti-Myc-agarose beads (Sigma) were used for co-immunoprecipitation. The eluted proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis using mouse anti-Myc (9E10) (1:2,000; Sigma) and rat anti-HA antibodies (3F10) (1:2,000; Roche Applied Science).

Disaccharide Analysis

Glycosaminoglycan isolation and disaccharide composition analysis were carried out as described previously (4, 25, 33). Approximately 200 mg of adult flies was used to isolate glycosaminoglycans. The glycosaminoglycan sample was digested with a heparitinase mixture (Seikagaku), and the resulting disaccharide species were separated using reversed-phase ion pair chromatography. The effluent was monitored fluorometrically for postcolumn detection of HS disaccharides. Similarly, glycosaminoglycan sample was digested with chondroitinases, and compositions of unsaturated chondroitin sulfate (CS) disaccharides ΔDi-0S and ΔDi-4S were analyzed by reversed-phase ion pair chromatography.

RESULTS

Isolation of Drosophila Hsepi Mutants

The Drosophila genome has a single copy of Hsepi homologue as in the mammalian genome. To analyze the in vivo function of Drosophila Hsepi, we isolated mutations deleting the Hsepi locus by imprecise excision of a P-element inserted in the 5′-untranslated region of the Hsepi gene. The isolated Hsepid12 and Hsepid13 alleles remove virtually the entire Hsepi coding sequence (Fig. 1A). Sequencing analysis of genomic DNA isolated from these mutants showed that both alleles lack most of the protein coding sequence, including the region containing multiple histidine and tyrosine residues crucial for C5-epimerase enzymatic activity (34), suggesting that they are molecularly null. The Hsepid13 allele additionally removes the 5′-portion of an upstream gene, CG3271. The homozygous mutants for Hsepid12 and Hsepid13 are viable and fertile with modest levels of lethality at larval and pupal stages (Table 1). We confirmed the amorphic nature of Hsepid12 by genetic experiments using a deficiency line, Df(2R)cn88b, which lacks the cytological region 42A1-E7, including the entire Hsepi locus. Lethality of Hsepid12 homozygotes (18.3%) was equivalent to that of their deficiency transheterozygotes (Hsepid12/Df(2R)cn88b; 19.3%), indicating that it is a null allele. We used Hsepid12 allele for the following experiments.

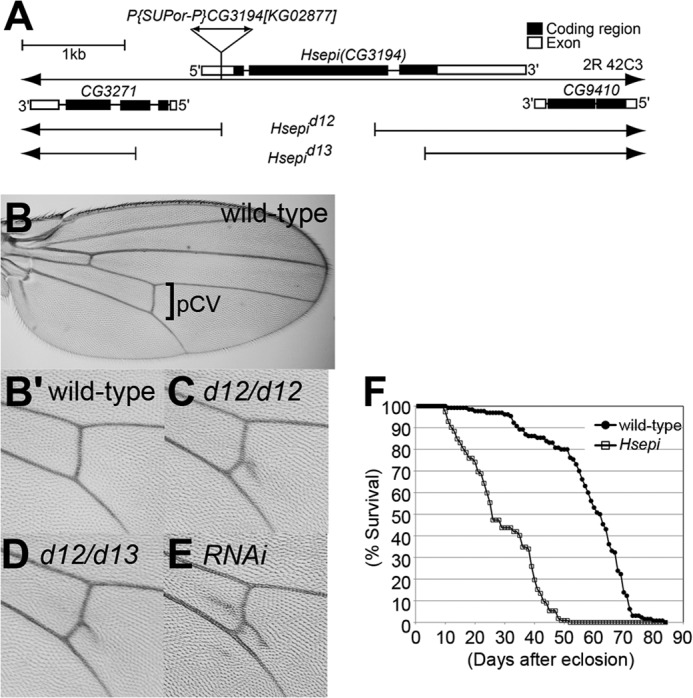

FIGURE 1.

Structure of Drosophila Hsepi gene. A, schematic diagram of Hsepi genomic region. A P-element insertion, P{SUPor-P}CG3194[KG02877], was used for the imprecise excision to isolate excision alleles. Filled boxes and open boxes indicate the protein coding sequence and untranslated regions, respectively. Hsepid12 and Hsepid13 lack most of the protein coding sequence, including the residues critical for C5-epimerase enzymatic activity. Hsepid13 also removes the 5′-portion of an upstream gene, CG3271. B–E, ectopic vein formation of Hsepi mutants. Adult wings are shown for wild type (B and B′), Hsepid12 (C), Hsepid12/Hsepid13 (D), and hh-Gal4/UAS-Hsepi RNAi (E). High magnification views for the pCV region are presented (B′, C, D, and E). F, survival curve of wild-type (closed circles) and Hsepi mutant (open boxes) adult flies. A 57% decrease in mean survival was observed in Hsepi mutants (n > 110; log rank test, p < 0.0001).

TABLE 1.

Lethality of mutants for HS-modifying enzymes

Lethality was determined using the following alleles: Hsepid12, Hs2std267, Hs6std770, and Sulf1P1. For each genotype, more than 100 progenies were counted.

| Genotype | Lethality |

|---|---|

| % | |

| Hsepi | 18.3 |

| Hsepi/Df(2R)cn88b | 19.3 |

| Hs2st | 27.6 |

| Hs2st Hsepi | 37.5 |

| Hs6st | 21.0 |

| Hsepi; Hs6st | 100.0 |

| Sulf1 | 8.0 |

| Hsepi; Sulf1 | 62.0 |

| Hsepi; dally | 100.0 |

Adult survivors show only modest morphological phenotypes, such as extra vein materials at the posterior crossvein (pCV) region of the wing (Fig. 1C). The penetrance of this phenotype was 25% in males and 90% in females (n > 100). This phenotype was also observed in Hsepid12/Hsepid13 transallelic mutants (Fig. 1D; penetrance >90%, n > 100) as well as Hsepi RNAi animals (hh-Gal4/UAS-Hsepi RNAi; Fig. 1E; penetrance >90%, n > 100), confirming the specificity of this phenotype. Despite relatively normal development and fertility of the adult survivors of Hsepi mutants, the longevity of mutant adults is remarkably shorter than wild type (Fig. 1F). The median of adult longevity of Hsepi mutants was 27 days, whereas it was 63 days in wild type. Thus, mutation of Hsepi has a relatively modest effect on morphogenesis and development but is indispensable for normal lifespan. Although the mechanism by which Hsepi ensures normal lifespan remains to be elucidated, given that HSPGs are essential regulators of female germ line stem cells (35), it is possible that Hsepi affects longevity through its functions in adult stem cell niches.

Expression Patterns of Hsepi mRNA

We next examined expression patterns of Hsepi mRNA during development by RNA in situ hybridization. We found that Hsepi is expressed ubiquitously throughout larval tissues, including the wing disc (Fig. 2A), eye-antennal disc (Fig. 2B), and larval CNS (Fig. 2D). This is consistent with the idea that C5-epimerization is a critical step in HS biosynthesis and required in all cells that produce HSPGs.

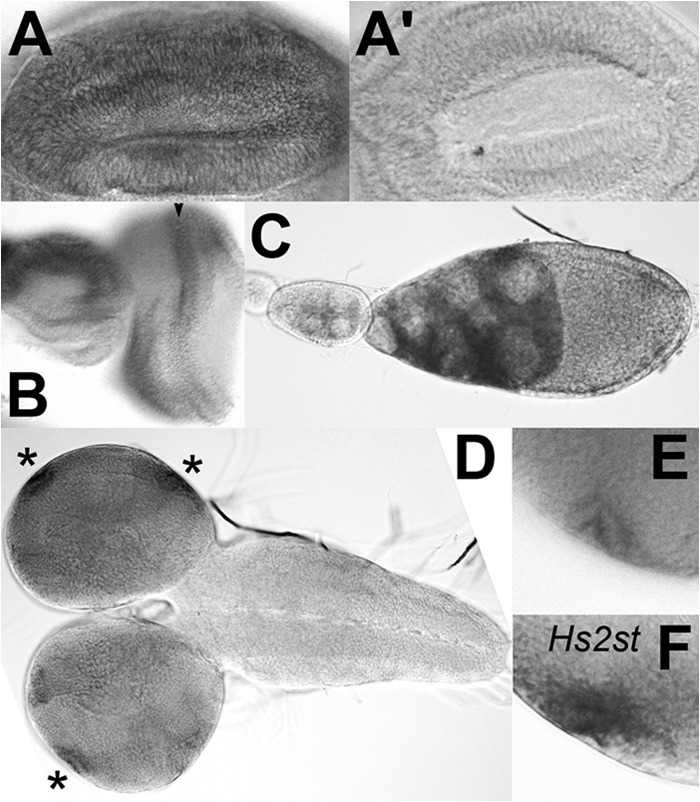

FIGURE 2.

In situ hybridization of Hsepi mRNA. A–E, in situ hybridization revealed ubiquitous but non-uniform expression of Hsepi mRNA in various tissues, including the wing disc (A and A′), eye-antennal disc (B), adult ovary (C), and larval CNS (D and E). High levels of Hsepi expression were detected in the morphogenetic furrow in the eye disc (C, arrowhead) and in the lamina furrow in the optic lobe of the CNS (D, asterisks). E shows a high magnification view of the lamina furrow. F shows the same region of the CNS as E that was hybridized with an Hs2st antisense probe. A′ shows a control wing disc hybridized with an Hsepi sense probe.

In situ hybridization also revealed non-uniform expression patterns of Hsepi mRNA in several tissues. For example, high levels of Hsepi mRNA were detected in the nurse cells in the adult ovary (Fig. 2C). We recently found that Syndecan is expressed on the surface of nurse cells (data not shown). We have shown previously that glypicans play critical roles in somatic cells in the ovary, affecting germ line development (35, 36). The findings of Hsepi/Syndecan expression in the nurse cells suggest a possible cell-autonomous role of HSPGs in germ line cells. It is also likely that a portion of Hsepi mRNA may be transported to the oocyte to be stored as maternal mRNA for embryogenesis.

The Hsepi transcript was detected at much higher levels in the morphogenetic furrow of the eye disc (Fig. 2B) and at the lamina furrow of the optic lobe (Fig. 2, D and E) than in other cells in these organs. It is worth noting that these cells express high levels of Hs2st (Fig. 2F and data not shown) and dally, which encodes a core protein of the glypican family of HSPGs (37). It is therefore possible that these cells have a higher level of activity of the HS biosynthetic machinery.

Disaccharide Structures of Hsepi Mutant HS

To study the effect of Hsepi mutation on HS sulfation patterns, disaccharide structures of HS isolated from Hsepi mutants were analyzed. HS was isolated from Hsepi and Hs2st mutant adults and completely digested into disaccharides by heparitinase, and the differentially modified disaccharide species were separated by high performance liquid chromatography. Although this assay does not distinguish GlcA- and IdoA-containing disaccharide units, it provides valuable information regarding HS structures from the mutants.

As reported previously (4), HS from Hs2st-null mutants showed a complete loss of 2S-containing disaccharide units with a remarkable increase of 6-O-sulfated disaccharides (Table 2 and Fig. 3A). We have shown previously that this compensatory increase in 6-O-sulfation restores FGF signaling during tracheal system formation (4). The compensation mechanism also rescues Wingless and BMP signaling (5).

TABLE 2.

Disaccharide analyses of HS from Hsepi, Hs2st, and Hs2st Hsepi double mutant animals

The disaccharide composition of HS is shown for each respective genotype. The values are given as mol % of total disaccharides and represent mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. NAc, ΔUA-GlcNAc; NS, ΔUA-GlcNS; NAc6S, ΔUA-GlcNAc6S; NS6S, ΔUA-GlcNS6S; 2SNS, ΔUA2S-GlcNS; and 2SNS6S, ΔUA2S-GlcNS6S; ND, not detectable. A graphical depiction of these results is shown in Fig. 3.

| HS (unsaturated disaccharide) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAc | NS | NAc6S | NS6S | 2SNS | 2SNS6S | |

| % | ||||||

| Wild type | 37.5 ± 1.2 | 25.4 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 17.6 ± 0.7 | 14.2 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.4 |

| Hsepi | 30.4 ± 0.9 | 35.4 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 32.4 ± 0.8 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | ND |

| Hs2st | 36.2 ± 1.2 | 25.1 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 36.7 ± 1.0 | ND | ND |

| Hs2st Hsepi | 29.2 ± 0.9 | 41.4 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 28.5 ± 0.6 | ND | ND |

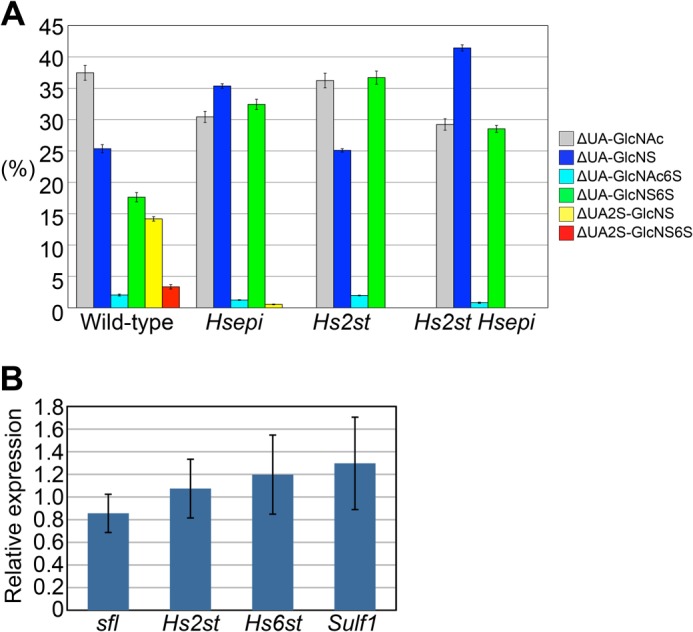

FIGURE 3.

HS disaccharide profiling of Hsepi mutants. A, graphical depiction of disaccharide composition of HS from each respective genotype. Bar graphs show percentages of the following disaccharides: ΔUA-GlcNAc (gray), ΔUA-GlcNS (blue), ΔUA-GlcNAc6S (light blue), ΔUA-GlcNS6S (green), ΔUA2S-GlcNS (yellow), and ΔUA2S-GlcNS6S (red). The values were obtained from three independent experiments, and each bar represents the mean ± S.D. B, quantitative PCR analysis of the mRNA levels of the indicated genes in Hsepi mutants relative to wild-type animals. Data are presented as the mean fold change with S.D. (n = 6). Expression levels of sfl, Hs2st, Hs6st, and Sulf1 genes are not significantly altered in Hsepi mutants (p > 0.1). Error bars represent S.D.

We found that overall disaccharide patterns of Hsepi mutant HS were similar to those of Hs2st. Hsepi mutant HS showed a substantial reduction of 2-O-sulfate groups, reflecting the strong preference of Hs2st for IdoA as a substrate, and a parallel increase of N- and 6-O-sulfate groups (Table 2 and Fig. 3A). Thus, Hsepi mutation also induces compensatory up-regulation of 6-O-sulfation as observed in Hs2st. This suggests that the mild morphological phenotypes of Hsepi mutants are due to the compensatory increase in 6-O-sulfation as shown in Hs2st. Although overall patterns were similar, there were a couple of notable differences between the two mutants. First, a residual peak was detectable for the ΔUA2S-GlcNS unit. Because Hsepi-null animals produce no IdoA-containing units, this peak should represent GlcA2S. In fact, GlcA2S was found to be increased in HS from Hsepi−/− mice (18). Second, the increase of 6-O-sulfation was less prominent in Hsepi compared with Hs2st. Instead, a significant increase of NS was observed in Hsepi but not in Hs2st mutants. These features are consistent with the results obtained in Hsepi−/− mice (10, 18).

Does C5-epimerization play a role in HS sulfation compensation? To determine whether Hsepi affects the compensatory increase in the level of 6-O-sulfation in Hs2st mutants, we examined the disaccharide profile of HS from Hs2st Hsepi double mutants. If C5-epimerization is important for HS compensation, one can expect that Hs2st Hsepi mutant HS does not have as high levels of 6-O-sulfation as that from Hs2st single mutants. We found that this was the case. In the double mutants, the level of NS6S units was significantly lower than in Hs2st, indicating that Hs2st mutation cannot efficiently increase 6-O-sulfation in the absence of Hsepi activity. These results indicated that, at the biochemical level, Hsepi contributes to at least a portion of the compensatory elevation of 6-O-sulfation in Hs2st mutants. With the reduction of 6-O-sulfation in the double mutants, reflected by the decreased level of NS6S units, there was a concurrent increase of NS units when compared with Hs2st single mutants. As a result, Hsepi mutation led to an increase of the N-sulfation/O-sulfation ratio.

We asked whether Hs2st, Hsepi, or Hs2st Hsepi mutations affect disaccharide composition of CS. Digestion of glycosaminoglycans with chondroitinases yields two disaccharide species, ΔDi-0S and ΔDi-4S (33). The ratio of these CS disaccharide units was not significantly altered in these mutant flies (Table 3). This result confirmed the HS-specific effects of these mutations.

TABLE 3.

Disaccharide analyses of chondroitin sulfate from Hsepi, Hs2st, and Hs2st Hsepi double mutant animals

The composition of unsaturated CS disaccharides ΔDi-0S and ΔDi-4S is shown for each respective genotype.

| CS (unsaturated disaccharide) |

||

|---|---|---|

| ΔDi-0S | ΔDi-4S | |

| % | ||

| Wild type | 87.7 | 12.3 |

| Hsepi | 87.5 | 12.5 |

| Hs2st | 88.0 | 12.0 |

| Hs2st Hsepi | 90.2 | 9.8 |

Because N- and 6-O-sulfate groups were increased in Hsepi mutants, we asked whether or not this change was accomplished by up-regulated expression of sfl, which encodes the only Drosophila NDST, and/or Hs6st. RT-quantitative PCR analysis revealed that expression levels of sfl, Hs2st, Hs6st, and Sulf1 genes were not significantly altered in Hsepi mutants (Fig. 3B). This result suggests that the compensatory sulfation changes in Hsepi mutants occur mainly through a mechanism that is independent of transcriptional control of HS-modifying enzymes.

Germ Line Development in Hs2st and in Hsepi Mutants

Because Hsepi mutation significantly reduced 2-O-sulfation, we compared phenotypes between Hs2st and Hsepi mutants. The most obvious difference between these mutants is their fertility. We have previously reported that Hs2st mutant flies develop all the way to adult stage, but both males and females of Hs2st mutant adults are completely sterile (4, 36). However, Hsepi mutant flies are viable and fertile. To understand the cellular basis for the fertility and sterility of these mutants, we analyzed the morphology of mutant ovaries. In particular, we focused on stalk formation, which is known to require HSPG activity. The stalk cells are a special type of follicle cells that separate developing egg chambers. The stalk cell differentiation is regulated by Jak/Stat signaling, and we recently demonstrated that this control is dependent on two glypican genes, dally and dally-like (dlp) (36). Dally and Dlp serve as co-receptors for Unpaired, a ligand of the Drosophila Jak/Stat pathway, and stalk cells are lost in mutant clones for sfl or dally/dlp. On the other hand, Hs2st mutant ovarioles showed an increased number of stalk cells (Fig. 4, B and E, and Ref. 36). Although the molecular mechanism of this defect is not fully understood, it is possible that Upd ligand distribution is altered in Hs2st mutants. In contrast, Hsepi mutants did not show this defect: the stalk cell number of Hsepi was almost the same as that of wild type (Fig. 4, C and E). We examined the stalk cell number of Hs2st Hsepi double mutants to investigate their genetic relationship. We found that the stalk cell phenotype in Hs2st Hsepi double mutants was closely similar to Hs2st single mutant flies with no obvious additional effect of Hsepi mutation to the Hs2st mutant phenotype (Fig. 4, D and E).

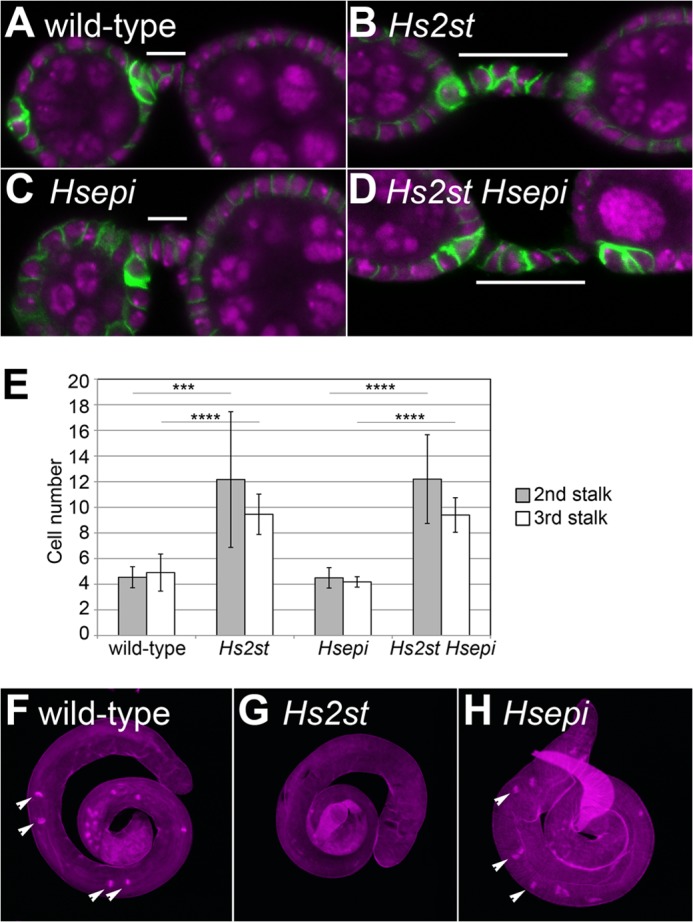

FIGURE 4.

Germ line development in Hs2st and Hsepi mutants. A–D, the ovaries are shown for wild-type (A), Hs2st (B), Hsepi (C), and Hs2st Hsepi (D) by staining with anti-FasIII antibody (green) and TOPRO-3 (magenta). The second stalk is marked with white bars. E, quantification of cell number in the second (gray) and third (white) stalks of the indicated genotypes is shown. ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; n > 25 for each genotype. Error bars represent S.D. F–H, testes from wild-type (F), Hs2st (G), and Hsepi (H) flies are shown. The penetrance of the Hs2st testis phenotype is 100% (n = 20). Staining with phalloidin (magenta) highlights the investment cones (arrowheads).

We also analyzed the male gonads of these mutants. Hs2st mutant testes are smaller than those of wild type (Fig. 4G). Phalloidin staining revealed the loss of the investment cones, which are a characteristic structure for elongated spermatids (38), suggesting that maturation of male germ cells failed in Hs2st mutant testes (Fig. 2, H–J). In contrast, overall morphology of Hsepi mutant testes was normal (Fig. 4H).

These analyses as well as normal fertility of Hsepi adult flies indicated that, unlike Hs2st, Hsepi appears to be dispensable for germ line development. The phenotypic difference between Hs2st and Hsepi mutant flies suggests that 2-O-sulfation but not C5-epimerization of HS chains plays critical roles in this process. Given that there should be no IdoA in the Hsepi mutant flies due to the loss of C5-epimerization activity, the existence of 2-O-sulfated GlcA may be sufficient for germ line development.

Genetic Interactions between Hsepi and HSPG Core Protein Genes during Wing Margin Formation

To further analyze the role of Hsepi in development, we examined the genetic interactions between Hsepi and HSPG core protein genes. Previous studies have established that HSPGs regulate multiple patterning events during wing/notum development, including the formation of sensory bristles at the wing margin (29), wing veins (37), and tracheoblast in the wing disc (4). In this study, we used these phenotypes as readouts for our genetic interaction assays.

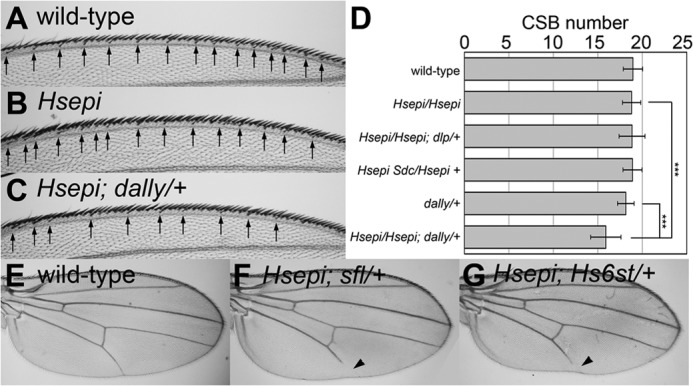

It has been shown previously that the number of chemosensory bristles is reduced in dally mutant flies (29, 39, 40). This reflects the reduced Wingless signaling at the wing margin of the mutants. Bristle number was not affected in Hsepi homozygous mutants (Fig. 5B). In dally heterozygous mutants, the average number of these bristles was slightly lower than wild type, but the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 5D). In contrast, heterozygosity of dally in the Hsepi homozygous mutant background (Hsepi/Hsepi; dally/+) resulted in a decreased number of chemosensory bristles (Fig. 5, C and D). On the other hand, we did not detect such synergistic effect by deleting one copy of other HS core protein genes, dlp and syndecan (sdc), in this particular developmental context (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that Hsepi modifies HS chains on Dally during wing margin formation.

FIGURE 5.

Genetic interactions between Hsepi and HSPG core protein/HS-modifying enzyme genes. A–C, dorsal view of anterior wing margin of female wild-type (A), Hsepi (B), and Hsepi; dally/+ (C) adult wings. The arrows indicate positions of chemosensory bristles. D, bar graphs showing the number of chemosensory bristles (CSB) in female wings of the indicated genotypes. ***, p < 0.001. Error bars represent S.D. E–G, female adult wings are shown for wild-type (E), Hsepi; sfl/+ (F), and Hsepi; Hs6st/+ (G). Arrowheads point to truncated wing vein V.

Remarkably, we found that Hsepi and dally double mutants were completely lethal (Table 1). This strong genetic interaction suggests that Dally is an important substrate for Hsepi. In addition, this synthetic lethal effect also indicates that Hsepi acts on the other HSPG core proteins too in another developmental process. If Hsepi only modified HS chains on Dally, then dally would be genetically epistatic to Hsepi (phenotypes of Hsepi; dally would be the same as dally single mutants). Thus, the phenotypic differences between dally (semilethal) and Hsepi; dally (lethal) reflect the function of other HSPG molecules.

Genetic Interactions between Hsepi and HS-modifying Enzymes during Wing Vein Formation

We next examined the genetic interaction between Hsepi and other HS-modifying enzymes. No abnormality was observed in longitudinal wing vein structures of Hsepi homozygous mutant flies (data not shown). Similarly, heterozygous mutants of sfl (sfl/+) have wild-type wings. In contrast, heterozygosity of sfl in the Hsepi homozygous mutant background (Hsepi/Hsepi; sfl/+) resulted in a truncation of longitudinal vein L5 (Fig. 5F; the penetrance was 85.3% in female, n = 34). Similarly, Hsepi/Hsepi; Hs6st/+ also showed a reduction of the wing vein L5, whereas the penetrance was lower than that in Hsepi/Hsepi; sfl/+ (Fig. 5G; the penetrance was 51.9% in female, n = 52). These synergistic enhancements of Hsepi phenotypes by these mutations reflect intimate functional relationships of these HS modification enzymes during wing vein formation.

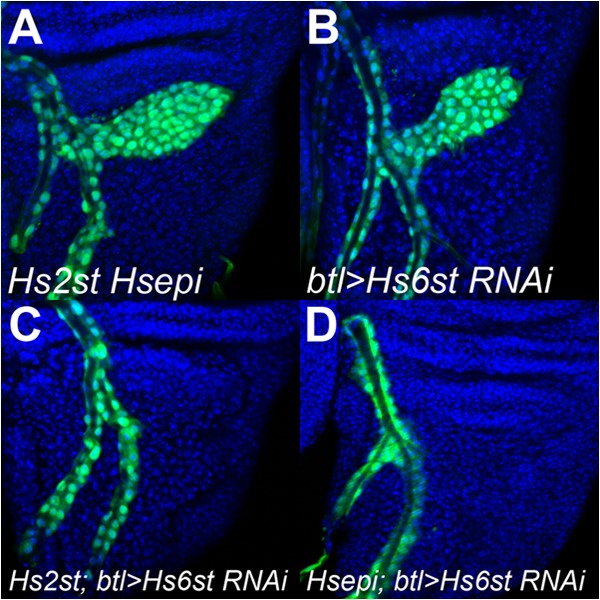

An Increase in 6-O-Sulfation Is Critical for the Rescue of Tracheoblast Formation in Hsepi Mutants

We have shown previously that the compensatory increase of 6-O-sulfation in Hs2st mutants is critical for the rescue of the mutants and that Hs2st; Hs6st double mutants fail to restore FGF, Wingless, and BMP signaling (4, 5). Our disaccharide analysis data revealed a substantial increase 6-O-sulfation in Hsepi mutants as observed in Hs2st mutants (Fig. 3). Therefore, we hypothesized that this increased 6-O-sulfation plays a role in the restoration of developmental pathways and the survival of Hsepi mutants. In fact, Hsepi; Hs6st double mutants are completely lethal (Table 1). To further test this idea, we analyzed the effect of Hs6st RNAi on FGF signaling during tracheoblast formation, a well known FGF-dependent process, in an Hsepi mutant background. No defect was observed in tracheoblasts in Hsepi mutant wing discs (data not shown) as reported in Hs2st mutants (4). Similarly, tracheoblasts of Hs2st Hsepi double mutants were indistinguishable from wild type (Fig. 6A). In addition, we did not detect any defect when an Hs6st RNAi construct was expressed in tracheoblasts by a breathless-Gal4 driver at 25 °C (btl>Hs6st RNAi) (Fig. 6B; n = 24). We have shown that the knockdown of Hs6st in this condition partially but significantly reduces Hs6st mRNA levels (5). In contrast, as we have reported previously (4), Hs6st knockdown in the same condition under Hs2st mutant background (Hs2st; btl>Hs6st RNAi) severely interfered with tracheoblast formation (Fig. 6C; penetrance, 50.0%; n = 24). We observed the same effect in Hsepi or in Hs2st Hsepi backgrounds: tracheoblast formation was strongly blocked in Hsepi; btl>Hs6st RNAi (Fig. 6D; penetrance, 50.0%; n = 24) and in Hs2st Hsepi; btl>Hs6st RNAi (data not shown). These results suggest that tracheoblast formation in Hsepi mutants is rescued by increased 6-O-sulfation as observed in Hs2st mutants.

FIGURE 6.

6-O-Sulfation is required for the rescue of tracheoblast formation in Hsepi mutants. Tracheoblast formation is shown in Hs2st Hsepi; btl-Gal4 UAS-GFP/+ (A), btl-Gal4 UAS-GFP/UAS-Hs6st RNAi (B), Hs2st; btl-Gal4 UAS-GFP/UAS-Hs6st RNAi (C), Hsepi; btl-Gal4 UAS-GFP/UAS-Hs6st RNAi (D). Tracheal cells are visualized by UAS-GFP expression driven by btl-Gal4 (green). Blue shows counterstaining by TOPRO-3.

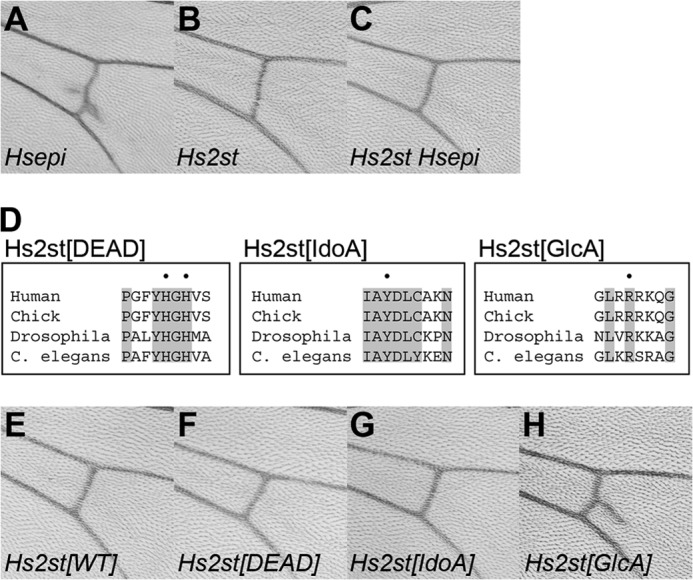

Ectopic Vein Phenotype Is Associated with Elevated 2-O-Sulfated GlcA

As stated above, Hsepi mutants showed ectopic vein materials at the pCV region (Figs. 1, C–E, and 7A). Interestingly, this phenotype was not observed in Hs2st-null mutant wings (Fig. 7B). In addition, Hs2st Hsepi double mutants did not exhibit this phenotype, indicating that the ectopic pCV phenotype of Hsepi mutants was suppressed by Hs2st mutation (Fig. 7C). Given that HS from Hsepi mutants but not Hs2st or Hs2st Hsepi double mutants includes GlcA2S, these results raised the possibility that the ectopic pCV phenotype may be associated with abnormal GlcA 2-O-sulfation.

FIGURE 7.

Ectopic vein phenotype is associated with elevated 2-O-sulfated GlcA. A–C, the pCV region of adult wings is shown for Hs2st (A), Hsepi (B), and Hs2st Hsepi (C) mutants. D, alignment of Hs2st amino acid sequences from different organisms (human, chick, Drosophila, and C. elegans). Sequences around vertebrate Hs2st His-140/His-142 (Hs2st[DEAD]), Tyr-94 (Hs2st[IdoA]), and Arg-189 (Hs2st[GlcA]) are shown. Positions of these residues are dotted, and residues conserved among all four species are highlighted. To generate each Drosophila mutant construct, the dotted residues were substituted to Ala. E–H, the pCV region of adult wings is shown for hh-Gal4/UAS-Hs2st[WT] (E), hh-Gal4/UAS-Hs2st[DEAD] (F), hh-Gal4/UAS-Hs2st[IdoA] (G), and hh-Gal4/UAS-Hs2st[GlcA] (H).

To test this hypothesis, we generated mutant forms of Drosophila Hs2st based on previous structure-based mutational studies of vertebrate Hs2sts that identified residues responsible for the catalytic activity and substrate specificity of these enzymes (Refs. 26 and 27 and Fig. 7D). For example, histidine residues at 140 and 142 are important for catalysis, and the double mutant H140A/H142A resulted in complete loss of activity (26). Several amino acid residues that had an impact on substrate specificity were also identified: Y94A and R189A mutants showed a substantial preference for IdoA-containing and GlcA-containing substrates, respectively. All these residues are completely conserved in Drosophila Hs2st (Fig. 7D). In fact, these residues are perfectly conserved in all Hs2st homologues from various species thus far available in GenBankTM, supporting the evolutionary conservation of the function of these specific residues. We generated three mutant constructs, Hs2st[DEAD], Hs2st[IdoA], and Hs2st[GlcA], that bear mutations equivalent to vertebrate H140A/H142A, Y94A, and R189A, respectively. Transgenic strains bearing UAS constructs for each mutant cDNA as well as wild-type Hs2st were generated by site-specific integration at the genomic location 68E (28). Overexpression of wild-type Hs2st in the posterior compartment of the developing wing by the hh-Gal4 driver did not show any obvious defect in the adult wing (Fig. 7E), consistent with a previous report (41). Similarly, no pCV phenotype was observed in the wings overexpressing Hs2st[DEAD] or Hs2st[IdoA] (Fig. 7, F and G; n > 20 for each genotype). In contrast, overexpression of Hs2st[GlcA] by hh-Gal4 produced ectopic vein materials at the pCV region, mimicking the phenotype observed in Hsepi mutant flies (Fig. 7H; penetrance, 94.7%; n = 19). Because these UAS transgenes have been integrated into the same genomic location, the phenotypic difference reflects the activity of each construct rather than differential expression levels due to positional effects. Taken together, these results support the idea that the ectopic pCV phenotype is associated with increased levels of GlcA2S.

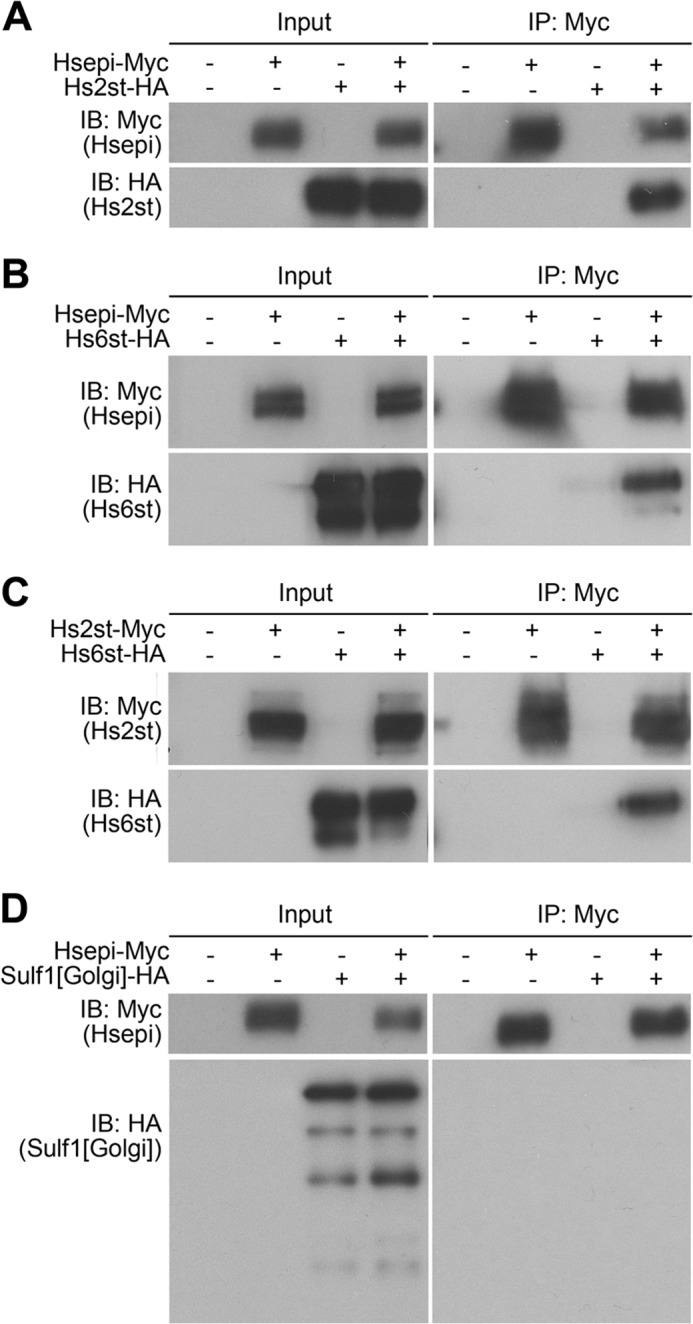

Physical Interaction of HS Modification Enzymes

It has been shown that Hs2st and Hsepi form a complex in mammalian cultured cells (6). We first tested whether this physical interaction is conserved in Drosophila enzymes by co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Drosophila S2 cells were co-transfected with Myc-tagged Hsepi and HA-tagged Hs2st expression constructs. Upon immunoprecipitation of Hsepi-Myc from a protein extract of the transfected cells, Hs2st-HA was detected in the immunoprecipitates by immunoblotting (Fig. 8A). This result indicated that, as in the case of mammalian homologues, Drosophila Hsepi and Hs2st physically interact with one another in S2 cells.

FIGURE 8.

Physical interaction of Hs2st, Hs6st, and Hsepi in S2 cells. Co-immunoprecipitation results are shown for Hsepi-Myc and Hs2st-HA (A), Hsepi-Myc and Hs6st-HA (B), Hs2st-Myc and Hs6st-HA (C), and Hsepi-Myc and the Golgi-tethered form of Sulf1 (Sulf1[Golgi]-HA) (D). Myc-tagged proteins were recovered from cell lysate by anti-Myc-agarose beads and eluted with urea. Precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-HA and anti-Myc antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblotting.

The sulfation compensation system requires a close functional relationship between Hs2st and Hs6st: 6-O-sulfation was increased in response to the loss of Hs2st or Hsepi. Therefore, we tested the possibility that Hs6st also physically interacts with Hsepi or Hs2st. Similar co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that Hs6st-HA was co-immunoprecipitated with both Hs2st-Myc and Hsepi-Myc (Fig. 8, B and C). This finding suggests that these three HS modification enzymes can form a molecular complex in S2 cells. Neither wild type (data not shown) nor the Golgi-tethered form of Sulf1, an extracellular HS 6-O-endosulfatase, showed an interaction with Hsepi (Fig. 8D), supporting that the observed binding among Hsepi-Hs2st-Hs6st is specific.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that Hsepi function is critical for normal animal development (10–14). C5-Epimerization plays a crucial role for signal transduction by providing a substrate for 2-O-sulfation (42). Furthermore, it has been suggested that FGF2 signaling is dependent on the synthesis of IdoA rather than on 2-O-sulfation per se (18). We found that overall Drosophila Hsepi-null mutants are significantly healthier than Hs2st mutants. For example, Hs2st but not Hsepi mutants showed morphological defects in both female and male gonads, leading to sterility. This was an unexpected finding since C5-epimerization is an upstream event of 2-O-sulfation, which is known to be heavily dependent on the epimerization reaction. In addition, Hsepi−/− mice showed defects equivalent to or more severe than those of Hs2st−/− mice, leading to lethality at earlier stages (10, 18). One mechanism that appears to contribute to the mild phenotypes of Hsepi mutants is HS sulfation compensation. We showed that 6-O-sulfation is dramatically elevated in these mutants. Thus, compensatory up-regulation of 6-O-sulfate groups may be responsible for rescue of HS-dependent pathways in Hsepi mutant flies as observed in Hs2st mutant animals (4, 5). Consistent with this idea, Hsepi; Hs6st mutants are completely lethal (Table 1). Tracheal cell-specific knockdown of Hs6st in an Hsepi mutant background inhibited tracheoblast formation (Fig. 6); thus, the increased 6-O-sulfation indeed rescued this FGF-dependent process. Another possible mechanism for the mild phenotypes observed in Hsepi mutants is that GlcA2S-containing units play a role and contribute to tissue patterning. This issue is discussed later.

Despite the clear importance of increased 6-O-sulfation in rescuing Hs2st and Hsepi mutant phenotypes, it is not understood how this compensation occurs. In Hs2st mutants, 6-O-sulfation is up-regulated in compensation, rescuing morphogenesis and HS-dependent molecular pathways, including FGF, Wnt, and BMP signaling (4, 5). Our HS disaccharide analyses revealed that the increase of 6-O-sulfation in Hs2st mutants in the absence of Hsepi was not as remarkable as that in its presence. Thus, at the biochemical level, Hsepi is required for efficient HS sulfation compensation in Hs2st mutants. However, its role appeared to be relatively minor at the physiological level. If Hsepi activity is critical for Hs2st mutants to increase 6-O-sulfation, then one can expect Hs2st Hsepi double mutants to show more severe phenotypes compared with Hs2st mutants due to incomplete HS sulfation compensation. However, we detected no obvious difference between Hs2st and Hs2st Hsepi mutant phenotypes. Therefore, the reduction of the compensatory increase of 6-O-sulfation in Hs2st Hsepi detected in the disaccharide analysis may not cause any additional failure in rescuing signaling pathways. We observed strong genetic interactions between Hsepi and Hs6st. Hsepi; Hs6st double mutants were completely lethal, and Hs6st RNAi in an Hsepi mutant background inhibited tracheoblast formation, suggesting that Hsepi is required for HS sulfation compensation in Hs6st mutants. This is not surprising given that 2-O-sulfation was dramatically reduced in Hsepi mutants. Thus, the effect of Hsepi on the compensation mechanism in Hs6st may be indirect: Hsepi is important for 2-O-sulfation, which is critical for the rescue of Hs6st mutants.

Although the mechanism for HS sulfation compensation is unknown, it is achieved through close functional interactions between HS-modifying enzymes. From this respect, our finding that Hs6st physically interacted with Hs2st and Hsepi is intriguing. The gagosome was defined as a physical complex of HS biosynthetic/modifying enzymes committed to the assembly of HS (1). It was also proposed that the composition of the gagosome would affect HS fine structure. Physical interactions were shown for Hs2st and Hsepi (6) and for NDST and EXT2 (8). The existence of a complex of Hs2st and Hsepi with Hs6st raises an interesting possibility that the formation of a gagosome complex is important for proper sulfation compensation. Given that loss of one type of sulfation results in an increase of sulfation at different positions during sulfation compensation, gagosome complexes with different component compositions may have different kinetics. For example, a complex lacking Hs6st may have an enhanced Hs2st activity. Further study is needed to elucidate the in vivo mechanism of this remarkable feedback system.

Hsepi mutants showed ectopic vein formation at the pCV region. Because remarkably this phenotype was suppressed by Hs2st mutation, we hypothesized that this phenotype is associated with GlcA2S. Consistent with this model, we found that overexpression of an Hs2st mutant protein that preferentially adds a 2-O-sulfate group on GlcA phenocopies Hsepi mutant wings. Thus, abnormal crossvein formation is the first example of a specific developmental event that is associated with elevated GlcA2S levels. Furthermore, our results suggest that GlcA2S-containing units play a role in a specific developmental pathway, supporting the idea that it may rescue developmental processes in Hsepi mutants that are more severely affected in Hs2st mutants, such as germ line development. It is not known how GlcA2S can compensate for the lack of IdoA2S. Similarly, it is unknown how HS from Hs2st or Hs6st mutants can still mediate HS-dependent signaling pathways to some extent. One explanation for both phenomena would be that such HS chains are flexible enough to twist and bend to place sulfate groups at appropriate three-dimensional positions and form hydrogen bonds to specific residues of ligand proteins. It has been established that pCV formation is controlled by BMP signaling. In the pupal wing, a BMP ligand, Decapentaplegic, is expressed only in the longitudinal veins and directionally transported to the pCV primordial region (43–46). This directional transport is facilitated by the extracellular BMP-binding proteins Short gastrulation (Sog) and Crossveinless (Cv) (46). The formation of ectopic vein materials at the pCV suggests the failure of proper movement of BMP ligands toward the pCV position. It has been suggested that HSPGs are involved in pCV formation (39, 47). The phenotypes of Hsepi mutants and hh>Hs2st[GlcA] animals suggests that precise regulation of HS structures, particularly the levels of GlcA2S, is responsible for the directional transport of BMPs. However, the molecular mechanism for this control remains to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to K. Basler, the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, and the Bloomington Stock Center for reagents. We thank Dan Levings for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HD042769 (to H. N.).

- HSPG

- heparan sulfate proteoglycan

- HS

- heparan sulfate

- Hsepi

- glucuronyl C5-epimerase

- Hs2st

- heparan sulfate 2-O-sulfotransferase

- Hs6st

- heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase

- GlcNAc

- N-acetylglucosamine

- GlcA

- glucuronic acid

- IdoA

- iduronic acid

- pCV

- posterior crossvein

- NDST

- N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- EXT

- exostosin

- GlcA2S

- 2-O-sulfated GlcA

- IdoA2S

- 2-O-sulfated IdoA

- hh

- hedgehog

- btl

- breathless

- sfl

- sulfateless

- dlp

- dally-like

- sdc

- syndecan

- UAS

- upstream activation sequence

- CS

- chondroitin sulfate

- ΔDi-0S

- 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-3-O-(β-d-gluco-4-enepyranosyluronic acid)-d-galactose

- ΔDi-4S

- 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-3-O-(β-d-gluco-4-enepyranosyluronic acid)-4-O-sulfo-d-galactose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Esko J. D., Selleck S. B. (2002) Order out of chaos: assembly of ligand binding sites in heparan sulfate. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 435–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirkpatrick C. A., Selleck S. B. (2007) Heparan sulfate proteoglycans at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1829–1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Merry C. L., Gallagher J. T. (2002) New insights into heparan sulphate biosynthesis from the study of mutant mice. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kamimura K., Koyama T., Habuchi H., Ueda R., Masu M., Kimata K., Nakato H. (2006) Specific and flexible roles of heparan sulfate modifications in Drosophila FGF signaling. J. Cell Biol. 174, 773–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dejima K., Kleinschmit A., Takemura M., Choi P. Y., Kinoshita-Toyoda A., Toyoda H., Nakato H. (2013) The role of Drosophila heparan sulfate 6-O-endosulfatase in sulfation compensation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6574–6582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pinhal M. A., Smith B., Olson S., Aikawa J., Kimata K., Esko J. D. (2001) Enzyme interactions in heparan sulfate biosynthesis: uronosyl 5-epimerase and 2-O-sulfotransferase interact in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12984–12989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ledin J., Ringvall M., Thuveson M., Eriksson I., Wilén M., Kusche-Gullberg M., Forsberg E., Kjellén L. (2006) Enzymatically active N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase-2 is present in liver but does not contribute to heparan sulfate N-sulfation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35727–35734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Presto J., Thuveson M., Carlsson P., Busse M., Wilén M., Eriksson I., Kusche-Gullberg M., Kjellén L. (2008) Heparan sulfate biosynthesis enzymes EXT1 and EXT2 affect NDST1 expression and heparan sulfate sulfation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4751–4756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smeds E., Feta A., Kusche-Gullberg M. (2010) Target selection of heparan sulfate hexuronic acid 2-O-sulfotransferase. Glycobiology 20, 1274–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li J. P., Gong F., Hagner-McWhirter A., Forsberg E., Abrink M., Kisilevsky R., Zhang X., Lindahl U. (2003) Targeted disruption of a murine glucuronyl C5-epimerase gene results in heparan sulfate lacking l-iduronic acid and in neonatal lethality. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28363–28366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bülow H. E., Hobert O. (2004) Differential sulfations and epimerization define heparan sulfate specificity in nervous system development. Neuron 41, 723–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghiselli G., Farber S. A. (2005) D-Glucuronyl C5-epimerase acts in dorso-ventral axis formation in zebrafish. BMC Dev. Biol. 5, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feyerabend T. B., Li J. P., Lindahl U., Rodewald H. R. (2006) Heparan sulfate C5-epimerase is essential for heparin biosynthesis in mast cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 195–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Townley R. A., Bülow H. E. (2011) Genetic analysis of the heparan modification network in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16824–16831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bullock S. L., Fletcher J. M., Beddington R. S., Wilson V. A. (1998) Renal agenesis in mice homozygous for a gene trap mutation in the gene encoding heparan sulfate 2-sulfotransferase. Genes Dev. 12, 1894–1906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Merry C. L., Wilson V. A. (2002) Role of heparan sulfate-2-O-sulfotransferase in the mouse. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1573, 319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grobe K., Ledin J., Ringvall M., Holmborn K., Forsberg E., Esko J. D., Kjellén L. (2002) Heparan sulfate and development: differential roles of the N-acetylglucosamine N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase isozymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1573, 209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jia J., Maccarana M., Zhang X., Bespalov M., Lindahl U., Li J. P. (2009) Lack of l-iduronic acid in heparan sulfate affects interaction with growth factors and cell signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15942–15950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rong J., Habuchi H., Kimata K., Lindahl U., Kusche-Gullberg M. (2001) Substrate specificity of the heparan sulfate hexuronic acid 2-O-sulfotransferase. Biochemistry 40, 5548–5555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindahl B., Eriksson L., Lindahl U. (1995) Structure of heparan sulphate from human brain, with special regard to Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. J. 306, 177–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin X., Perrimon N. (1999) Dally cooperates with Drosophila Frizzled 2 to transduce Wingless signalling. Nature 400, 281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsuda M., Kamimura K., Nakato H., Archer M., Staatz W., Fox B., Humphrey M., Olson S., Futch T., Kaluza V., Siegfried E., Stam L., Selleck S. B. (1999) The cell-surface proteoglycan Dally regulates Wingless signalling in Drosophila. Nature 400, 276–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson K. G., Ghose A., Epstein E., Lincecum J., O'Connor M. B., Van Vactor D. (2004) Axonal heparan sulfate proteoglycans regulate the distribution and efficiency of the repellent slit during midline axon guidance. Curr. Biol. 14, 499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirkpatrick C. A., Dimitroff B. D., Rawson J. M., Selleck S. B. (2004) Spatial regulation of Wingless morphogen distribution and signaling by Dally-like protein. Dev. Cell 7, 513–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kleinschmit A., Koyama T., Dejima K., Hayashi Y., Kamimura K., Nakato H. (2010) Drosophila heparan sulfate 6-O endosulfatase regulates Wingless morphogen gradient formation. Dev. Biol. 345, 204–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu D., Song D., Pedersen L. C., Liu J. (2007) Mutational study of heparan sulfate 2-O-sulfotransferase and chondroitin sulfate 2-O-sulfotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 8356–8367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bethea H. N., Xu D., Liu J., Pedersen L. C. (2008) Redirecting the substrate specificity of heparan sulfate 2-O-sulfotransferase by structurally guided mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18724–18729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F., Basler K. (2007) An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific φC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3312–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fujise M., Izumi S., Selleck S. B., Nakato H. (2001) Regulation of dally, an integral membrane proteoglycan, and its function during adult sensory organ formation of Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 235, 433–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fujise M., Takeo S., Kamimura K., Matsuo T., Aigaki T., Izumi S., Nakato H. (2003) Dally regulates Dpp morphogen gradient formation in the Drosophila wing. Development 130, 1515–1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kamimura K., Fujise M., Villa F., Izumi S., Habuchi H., Kimata K., Nakato H. (2001) Drosophila heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase (dHS6ST) gene. Structure, expression, and function in the formation of the tracheal system. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17014–17021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akiyama T., Kamimura K., Firkus C., Takeo S., Shimmi O., Nakato H. (2008) Dally regulates Dpp morphogen gradient formation by stabilizing Dpp on the cell surface. Dev. Biol. 313, 408–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Toyoda H., Kinoshita-Toyoda A., Selleck S. B. (2000) Structural analysis of glycosaminoglycans in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans and demonstration that tout-velu, a Drosophila gene related to EXT tumor suppressors, affects heparan sulfate in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2269–2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li K., Bethea H. N., Liu J. (2010) Using engineered 2-O-sulfotransferase to determine the activity of heparan sulfate C5-epimerase and its mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11106–11113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hayashi Y., Kobayashi S., Nakato H. (2009) Drosophila glypicans regulate the germline stem cell niche. J. Cell Biol. 187, 473–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hayashi Y., Sexton T. R., Dejima K., Perry D. W., Takemura M., Kobayashi S., Nakato H., Harrison D. A. (2012) Glypicans regulate JAK/STAT signaling and distribution of the Unpaired morphogen. Development 139, 4162–4171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakato H., Futch T. A., Selleck S. B. (1995) The division abnormally delayed (dally) gene: a putative integral membrane proteoglycan required for cell division patterning during postembryonic development of the nervous system in Drosophila. Development 121, 3687–3702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. White-Cooper H. (2004) Spermatogenesis: analysis of meiosis and morphogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 247, 45–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takeo S., Akiyama T., Firkus C., Aigaki T., Nakato H. (2005) Expression of a secreted form of Dally, a Drosophila glypican, induces overgrowth phenotype by affecting action range of Hedgehog. Dev. Biol. 284, 204–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kirkpatrick C. A., Knox S. M., Staatz W. D., Fox B., Lercher D. M., Selleck S. B. (2006) The function of a Drosophila glypican does not depend entirely on heparan sulfate modification. Dev. Biol. 300, 570–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kamimura K., Maeda N., Nakato H. (2011) In vivo manipulation of heparan sulfate structure and its effect on Drosophila development. Glycobiology 21, 607–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Casu B., Lindahl U. (2001) Structure and biological interactions of heparin and heparan sulfate. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 57, 159–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ralston A., Blair S. S. (2005) Long-range Dpp signaling is regulated to restrict BMP signaling to a crossvein competent zone. Dev. Biol. 280, 187–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Serpe M., Ralston A., Blair S. S., O'Connor M. B. (2005) Matching catalytic activity to developmental function: tolloid-related processes Sog in order to help specify the posterior crossvein in the Drosophila wing. Development 132, 2645–2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shimmi O., Ralston A., Blair S. S., O'Connor M. B. (2005) The crossveinless gene encodes a new member of the Twisted gastrulation family of BMP-binding proteins which, with Short gastrulation, promotes BMP signaling in the crossveins of the Drosophila wing. Dev. Biol. 282, 70–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Matsuda S., Shimmi O. (2012) Directional transport and active retention of Dpp/BMP create wing vein patterns in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 366, 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen J., Honeyager S. M., Schleede J., Avanesov A., Laughon A., Blair S. S. (2012) Crossveinless d is a vitellogenin-like lipoprotein that binds BMPs and HSPGs, and is required for normal BMP signaling in the Drosophila wing. Development 139, 2170–2176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]