Background: Heme oxygenase (HO) converts heme to biliverdin, carbon monoxide, and Fe2+.

Results: HO crystal structures were determined for substrate-free Fe3+-biliverdin and biliverdin forms, as well as intermediates of the last two.

Conclusion: HO reaction center is built with substrate-induced conformational changes, and Fe2+ is released without major structural changes.

Significance: Elucidation of these HO structures is fundamental for understanding its enzyme mechanism.

Keywords: Enzyme Structure, Heme, Heme Oxygenase, Molecular Dynamics, X-ray Crystallography, Bacterial Iron Acquisition

Abstract

Heme oxygenase catalyzes the degradation of heme to biliverdin, iron, and carbon monoxide. Here, we present crystal structures of the substrate-free, Fe3+-biliverdin-bound, and biliverdin-bound forms of HmuO, a heme oxygenase from Corynebacterium diphtheriae, refined to 1.80, 1.90, and 1.85 Å resolution, respectively. In the substrate-free structure, the proximal and distal helices, which tightly bracket the substrate heme in the substrate-bound heme complex, move apart, and the proximal helix is partially unwound. These features are supported by the molecular dynamic simulations. The structure implies that the heme binding fixes the enzyme active site structure, including the water hydrogen bond network critical for heme degradation. The biliverdin groups assume the helical conformation and are located in the heme pocket in the crystal structures of the Fe3+-biliverdin-bound and the biliverdin-bound HmuO, prepared by in situ heme oxygenase reaction from the heme complex crystals. The proximal His serves as the Fe3+-biliverdin axial ligand in the former complex and forms a hydrogen bond through a bridging water molecule with the biliverdin pyrrole nitrogen atoms in the latter complex. In both structures, salt bridges between one of the biliverdin propionate groups and the Arg and Lys residues further stabilize biliverdin at the HmuO heme pocket. Additionally, the crystal structure of a mixture of two intermediates between the Fe3+-biliverdin and biliverdin complexes has been determined at 1.70 Å resolution, implying a possible route for iron exit.

Introduction

Heme oxygenase (HO)3 catalyzes regiospecific oxidative conversion of iron protoporphyrin IX (heme hereafter) to biliverdin IXα, iron, and CO, using three oxygen molecules and seven electrons. The enzyme is not a heme protein by itself and uses heme as both the active center and substrate (1). In mammalian systems, where electrons are supplied from NADPH through NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (2), HO is the enzyme responsible for heme degradation (1) and iron recycling (3). The product CO has been implicated as a messenger molecule in various physiological functions (4, 5). Although structural and functional studies have been conducted mostly on the soluble, truncated form of isoform-1 of mammalian HO, HO-1 (6), heme degradation enzymes are also present in some pathogenic bacteria where they are essential for heme-based iron acquisition from a host lacking in free extracellular iron (7, 8). Two families of heme degradation enzymes have been identified in iron acquisition systems of pathogenic bacteria (8). One is the IsdG-type enzymes, including IsdG and IsdI of Staphylococcus aureus and MhuD of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. They have the distinct ferredoxin-like structural fold with unusually ruffled heme distinct from those of canonical HO (8, 9). They degrade heme by multistep reductive oxidation reactions similar to HO (9, 10). However, their reactions produce tetrapyrrole products different from biliverdin without liberation of CO (10, 11). The other family is the HO-type enzyme that has spectroscopic and structural characteristics very similar to those of mammalian HO and follows the canonical HO reaction. Structures and catalytic properties of three HO proteins from pathogenic bacteria have been studied as follows: Corynebacterium diphtheriae HmuO (12), Neisseria meningitides HemO (13), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PigA (14). In comparison with the mammalian HO, neither of them is membrane-bound. Instead, they are soluble and have smaller molecular masses, i.e. 24 kDa for HmuO, 26 kDa for HemO, and 23 kDa for PigA. HmuO, one of the best studied bacterial HOs, has 33% sequence identity to the first 221 amino acids of human HO-1 (12). Despite their differences in size, the three bacterial HO proteins have overall protein folds, heme environments, and catalytic mechanisms similar to those for mammalian HO-1 (15–19), except for PigA that yields the δ biliverdin isomer, instead of the α isomer, the usual HO reaction product, due to a rotation of the heme group in an active site pocket (19).

Since the first report of the crystal structure of human HO-1 (20), x-ray crystallographic analysis, together with spectroscopic and enzymatic studies, has made a considerable contribution in our elucidation of the HO catalytic mechanism (6, 21–26). In HO catalysis, HO first binds heme to form a heme-enzyme complex, where the heme group is tightly sandwiched between the proximal and distal helices, the former of which includes the heme iron axial ligand His residue. The first electron donated from the reducing substrate converts the heme iron to the ferrous state. Then O2 binds to reduced penta-coordinate heme to form a meta-stable oxy complex. The crystal structure of the oxyheme-HmuO complex (26) reveals that the steric pressure of the distal helix realizes an acute Fe–O–O bond angle and directs the bound O2 toward the porphyrin α-meso-carbon atom. The terminal oxygen atom forms a favorable hydrogen bond with a nearby water molecule that is a part of an extended solvent hydrogen bond network anchored by a conserved Asp residue in the distal heme pocket. This network provides a channel for efficient proton transfer to the active site, which is required for formation of the ferric hydroperoxo species upon one electron reduction of the oxy form, activation of the O–O bond for cleavage, and regioselective hydroxylation of the α-meso-carbon, leading to formation of the ferric α-meso-hydroxyheme intermediate (6, 21, 23). Reaction of the α-meso-hydroxyheme intermediate with O2 and an electron affords the ferrous verdoheme intermediate. The last oxygenation step converts verdoheme to Fe3+-biliverdin by the same mechanism as the first oxygenation step, hydroxylation of the porphyrin α-meso-carbon (25). One-electron reduction of Fe3+-biliverdin releases Fe2+, and the HO catalytic product, biliverdin, is generated (27). Although the structural insight into HO catalytic mechanism has been realized by the crystal structures (17–26, 28), major questions remain to be answered in the substrate-free4 and the product-bound forms of HO.

The one remaining question is as follows. How is the active site of HO formed upon substrate heme binding? The crystal structures of the substrate-free forms of human and rat HO-1 have found that the major differences between the substrate-free and heme-bound structures are located at the vicinity of the heme-binding site with the “distal” and “proximal” helices in the substrate-free form being more flexible and open than those in their heme complexes (29, 30). The hydrogen bond between Gln-38 Nϵ and Glu-29 backbone carbonyl oxygen, present in the heme complex and absent in substrate-free HO-1, was reported as one of the key factors in forming the proximal side of the heme pocket during the heme binding (29). This notion cannot be applied for the heme binding in the three structurally characterized bacterial HO proteins where Gln-38 is not conserved; Gln-38 of HO-1 is substituted for Val in HemO and PigA and for Leu in HmuO (12–14). Fukuyama and co-workers (29) instead proposed that the heme-binding mechanism of N. meningitidis HemO was different from that of HO-1 in that the C-terminal loop participated in formation of the proximal side of the heme pocket of HemO (17). However, neither HmuO nor PigA has such a long C-terminal loop (18, 19). Another question regards the absence of the catalytically critical water hydrogen bond network reported for the human and rat substrate-free HO-1 structures, despite the high similarity in overall structure between the substrate-free and heme-bound forms. Crystal structures of the substrate-free forms of other HOs shall provide a new insight into the formation of the active site.

The second issue to be addressed is the structure and location of the product biliverdin in HO. In the crystal structure of the biliverdin complex of human HO-1 (31), the biliverdin group assumes an atypical twisted extended conformation different from the all-Z-all-syn-type helical structures found in biliverdin dimethyl ester (32), the biliverdin-apomyoglobin complex (33), and the biliverdin-biliverdin IXβ reductase complex (34). Furthermore, the distal pocket ordered water molecules are absent, and the biliverdin apparently moves out of the heme site into an adjacent internal cavity (31). The electron density map reported for the biliverdin group in human HO-1 does not seem to be well defined probably due to high mobility and possible multiple binding modes. Other crystal structures of the biliverdin-HO complex shall evaluate whether the extended conformation found in human HO-1 is a common structural feature of biliverdin in HO.

To this end, we have determined the crystal structures of the substrate-free HmuO, the Fe3+-biliverdin-HmuO complex, and the biliverdin-HmuO complex at 1.80, 1.90, and 1.85 Å resolution, respectively. In addition, the crystal structure of a mixture of two intermediate states from Fe3+-biliverdin to biliverdin has been determined at 1.70 Å resolution. The structure of the substrate-free HmuO has been further studied by MD simulations. Altogether, our results allow us to propose mechanisms for how HmuO forms the active site upon the substrate heme binding and how the enzyme releases its products, iron and biliverdin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Preparation and Crystallization

Expression and purification of HmuO and preparation and crystallization of the heme-HmuO complex were carried out as described previously (16, 18).

For crystallization of the substrate-free HmuO, the purified HmuO protein was concentrated to ∼1 mm in 20 mm MES, pH 7.0. The colorless and thin rod-shaped crystals were obtained by a hanging drop vapor diffusion method from a solution mixed with an equal volume of the protein solution and a reservoir solution containing 85 mm sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, 25.5% (w/v) PEG8000, 170 mm sodium acetate, and 23.5% (v/v) glycerol at 293 K. The substrate-free HmuO crystals were flash-frozen by a cold nitrogen stream.

The crystals of the biliverdin-HmuO complexes were prepared by in situ heme degradation using ascorbic acid as the electron donor. The crystals of the heme complex were transferred into a reservoir solution of 50 mm MES, pH 6.1, 2.2 m ammonium sulfate, and 25% (w/v) sucrose, supplemented with 200 mm sodium ascorbate for 9–19 h. In one case, very small and sheer crystals of the heme complex were selected and soaked into the reservoir solution supplemented with 60 mm instead of 200 mm sodium ascorbate and 10 mm sodium azide for 150 min. The crystal was then transferred into a solution of 50 mm MES, pH 6.1, 2.2 m ammonium sulfate, and 25% (w/v) sucrose. Crystals were picked up by nylon loops and flash frozen with ∼100 K N2 stream or liquid N2.

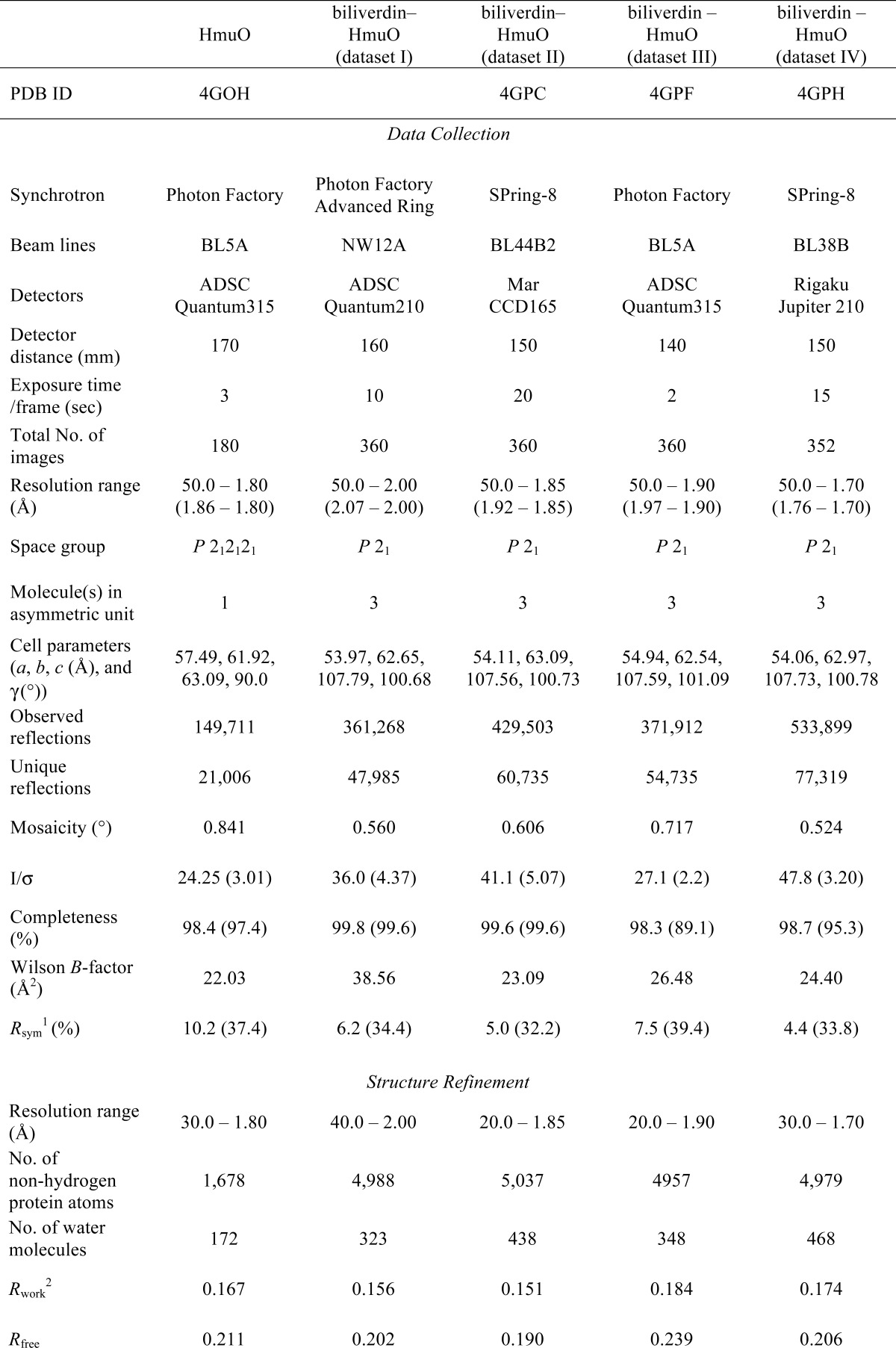

Intensity Data Collection

X-ray diffraction data were collected at SPring-8, Photon Factory, and Photon Factory Advanced Ring (Table 1). For the biliverdin complex, four sets of data, named datasets I to IV, were collected. The crystals soaked with 200 mm sodium ascorbate for 19 h yielded datasets I and II. The first dataset (dataset I) of 2.0 Å resolution was used for the preliminary structure determination. The second dataset (dataset II) was apparently better quality and used for the refinement to 1.85 Å resolution. The third dataset (dataset III) was on the crystal incubated with 200 mm sodium ascorbate for 9 h. The fourth dataset (dataset IV) was from the small crystal soaked with 60 mm sodium ascorbate and 10 mm sodium azide. The crystal yielded dataset IV was grown with intentions to arrest the HO reaction at the verdoheme stage, but apparently the HO reaction proceeded to steps beyond the Fe3+-biliverdin stage. All diffraction data, including the substrate-free crystal, were collected with 1.0 Å synchrotron radiation with a 1.0° oscillation angle, as listed in Table 1. The temperatures around the crystals were maintained at 95 K throughout data collection. Data were integrated, merged, and processed with HKL-2000 (35). The crystals of the substrate-free HmuO belonged to the orthogonal space group P212121 containing one molecule in the asymmetric unit. The crystals of the biliverdin complexes belonged to the space group P21 and contained three molecules in the asymmetric unit, as were the heme complex crystals (18). The diffraction statistics are also summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Statistics of data collection and structure refinement

1 Rsym = Σ|I−〈I〉|/ΣI.

2 R = Σ(|Fo| − |Fc|)/Σ|Fo|. The Rfree is the R calculated on the 10% reflections excluded for refinement.

Structure Determination and Refinement

Because the crystal of the biliverdin-HmuO complex was nearly isomorphous with that of the ferric heme complex (18), its initial structure was determined from dataset I by rigid-body refinement of CNS (36) using the crystal structure of the heme-HmuO complex (Protein Data Bank code 1IW0 (18)), from which three heme groups were omitted, as a search model. The phases were extended from 3.2 to 2.0 Å by density modifications, including solvent flattening, noncrystallographic symmetry averaging between three molecules, and histogram matching with program DM from the CCP4 suites (37). Simulated annealing (T = 4000 K) was carried out with CNS using the 40.0 to 2.0 Å resolution data. The model was revised with program O (38) and Turbo-Frodo (39) to fit the DM map. Further crystallographic refinements with simulated annealing and individual B factor refinement with CNS were performed to calculate an unbiased model. At this stage, the noncrystallographic symmetry restraint was removed, because each of the three molecules in the asymmetric unit had slightly different conformations, as was the case for the heme complex (18). After several refinement cycles, water molecules were added to the model by CNS and moved, removed, and/or added by manual inspection in the σA-weighted 2Fo − Fc and Fo − Fc maps with the program O. The model was further refined using the maximum likelihood target with the program REFMAC5 (40). After the introduction of alternative conformations for several residues and the translation-liberation-screw refinement (41), the R and Rfree factors dropped to 0.156 and 0.202, respectively. At this stage of the refinement, a better quality and higher resolution dataset (dataset II) was obtained. From dataset II, a better model for the biliverdin-HmuO complex structure was refined to 1.85 Å resolution by the procedures similar to those used for dataset I. The electron densities corresponding to biliverdin groups clearly appeared. The final R and Rfree factors were 0.151 and 0.190, respectively. The same refinement procedure was applied to datasets III and IV using the structure of the biliverdin complex as the starting model. The final R and Rfree factors are 0.184 and 0.239, respectively, at 1.90 Å resolution for dataset III and are 0.174 and 0.206, respectively, at 1.70 Å resolution for dataset IV.

For structural determination of the substrate-free form of HmuO, molecular replacement analysis was performed with CNS using molecule A of the biliverdin-HmuO complex, from which biliverdin was omitted, as a search model. The rotation and translation parameters were refined by rigid-body refinement using the observed reflections between 15.0 and 3.0 Å resolution. The highest peak of the correlation coefficient of the translation function (monitor value in CNS) was 0.530, which was significantly higher than the second unrelated peak 0.193. The model from the second peak was not generated in this structural analysis, but using the model calculated from the first peak, an R factor just after the rigid-body refinement converged to 0.403 at 3.0 Å resolution. The initial phases were calculated at 3.2 Å resolution with the atomic parameters obtained by the refinement. Further phase extension to 1.80 Å resolution was carried out by density modification coupled with solvent flattening and histogram matching with program DM from the CCP4 suites (37). Simulated annealing (T = 4000 K) with CNS using 30.0 to 1.80 Å resolution data dropped R and Rfree factors to 0.328 and 0.363, respectively. Model modification and structure refinements were carried out by the same procedures used for the biliverdin complex structure described above. The final R and Rfree factors for the substrate-free HmuO model were 0.167 and 0.211, respectively, at 1.80 Å resolution. All refinements were conducted using structure factors F > 0σF. Refinement statistics are given in Table 1. Bobscript (42), Raster3D (43), Turbo-Frodo (39), and PyMOL (44) were used to prepare figures.

MD Simulations

The initial structure for the MD simulations was taken from the HmuO crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 1IW0 (18)). Crystallographic water molecules were retained. After removing the heme molecule from the HmuO crystal structure, the protein was solvated with a 10-Å thick layer of TIP3P water molecules. Sodium ions were added to achieve charge neutrality. Conventional (pH 7) protonation states were chosen for all residues. The protonation state of the histidine residues took into account their hydrogen bond environment, and all aspartates and glutamates were taken as deprotonated to carboxylate anions. The Cornell et al. (45) force-field, as implemented in AMBER 7.0 (46), was used. The whole system (protein + solvent + counter ions) was relaxed with a gradient minimizer, and it was heated in several steps (100 K (50 ps), 200 K (25 ps), and 300 K (25 ps)) by coupling to a bath to achieve the desired temperature. Afterward, 200 ps of simulation at constant volume and 300 ps at constant pressure were performed to equilibrate the system, using a time step of 1 fs. The dynamics of the system was followed for 70 ns using the NAMD program (47). The hydrogen bonds were frozen during the dynamics using the SHAKE algorithm and the time step, was set to 2 fs.

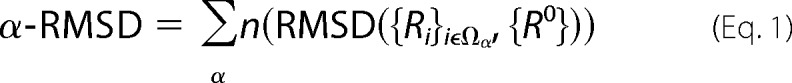

To describe the partial unfolding of the proximal helix, we used a collective variable (named α-RMSD) that measures the deviation of the backbone structure from an ideal α-helix (48) as shown in Equation 1,

|

where the sum goes for each 6-residue block and n is a function switching smoothly between 0 and 1, as shown in Equation 2.

|

The RMSD value is calculated as the distance matrix of the atoms in the set Ωα of six residues included in the collective variable (e.g. residues belonging to the proximal helix) with the distances of an “ideal” α-helix {R0}. The exponents n and m used were 8 and 12, respectively, and RMSD0 was taken as 0.6 nm.

|

Further details of the formulation can be found in Ref. 48. The α-RMSD value of the proximal helix is 6.4 in the substrate-bound HmuO but decreases to 3.5 in the substrate-free form. Therefore, α-RMSD is a good indicator of the proximal helix conformation.

RESULTS

Overall Structure of Substrate-free HmuO

The Cα trace of the substrate-free HmuO crystal structure is shown in Fig. 1A. In the structure, residues 5–215 are resolved. However, even after numbers of refinement cycles, the electron density maps for residues 14–23, which are in the proximal helix of the heme complex (A helix), are not sufficiently clear for unambiguous positioning the side chains of these residues. Consequently, the region, residues 14–23, has much higher averaged B factor (∼54.5 Å2) than the rest of the structure, which has the averaged B factor of ∼17.5 Å2. In the distal helix (H1 and H2 helices), some residual Fo − Fc electron density peaks appear around Gly-139 and Gly-140, two residues located very close to the heme iron in the heme complex (18). The regions around His-20 in the proximal helix and around Gly-139 and Gly-140 in the distal helix are rendered highly mobile in the substrate-free HmuO in comparison with the heme complex.

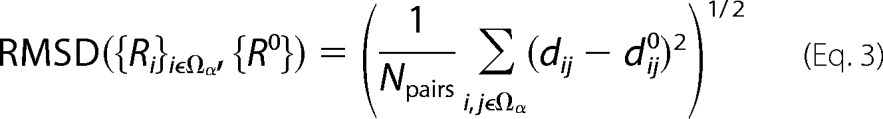

FIGURE 1.

Overall structure of the substrate-free HmuO and the ferric heme-HmuO complex. A and B, Cα traces of the substrate-free HmuO (A) and the ferric heme-HmuO complex (B). Each helix is labeled as A to J from the N terminus. C, superposition of the substrate-free HmuO and the ferric heme-HmuO complex. The substrate-free and heme-bound forms are colored in cyan and red, respectively. D, simulated annealed composite omit 2Fo − Fc map around the new loop region (Glu-24 to Phe-28) of HmuO at the 1.0 σ level. E, models for the proximal (helix A, residue 7–26), distal (helix H, residue 126–151), B (residue 28–35), and I (residue 169–179) helices are superimposed to minimize the r.m.s. deviation of the corresponding main chain atoms of all the amino acid residues. The substrate-free from is colored in cyan and the heme complex in red. The asterisk denotes the positions of the Glu-24 Cα atoms. These figures were prepared by PyMOL (44).

Comparison between the Substrate-free and the Heme-bound Forms of HmuO

The Cα trace of the substrate-free HmuO is compared with that of the heme complex (18) in Fig. 1, A–C. The r.m.s. deviation for the Cα atoms is 1.58 Å between the substrate-free form and the heme complex (molecule A, one of the three molecules of the crystallographic asymmetric unit). The overall structure of substrate-free HmuO is similar to that of the heme complex (Fig. 1C). The structure is consistent with the results of the substrate-free HmuO 1H NMR studies (49) in terms of structural conservation of the aromatic cluster and bulk of hydrogen bond network upon loss of the substrate heme.

There are four notable differences found between the crystal structures of the substrate-free and the heme-bound forms of HmuO. First, a structural segment of the proximal helix, which forms a conserved α-helix in the structurally characterized bacterial and mammalian heme-HO complexes (18–20, 32, 50), is unfolded in the substrate-free form, which is marked as “new loop” in Fig. 1A. As shown in Fig. 1D, the electron density map for the region (Glu-24–Thr-27) is very clear, and the structure of the region, including the side chains, is well defined. Residues from His-20 (equivalent to His-25 of HO-1) to Thr-27 unfold and extend into the solvent.

As depicted in Fig. 1E, the Glu-24 Cα atom moves 11.2 Å from its position in the heme complex with its side chain completely shifted away from the heme pocket. Carboxylate of Glu-24 forms an ionic or hydrogen bonding interaction with Nξ of Lys-213 near the C terminus (Fig. 2A). This interaction is absent in the heme complex in which His-20 and Glu-24 are a part of the proximal helix, and Nϵ of the former forms a hydrogen bonding interaction with Oϵ of the latter (Fig. 2B) (18).

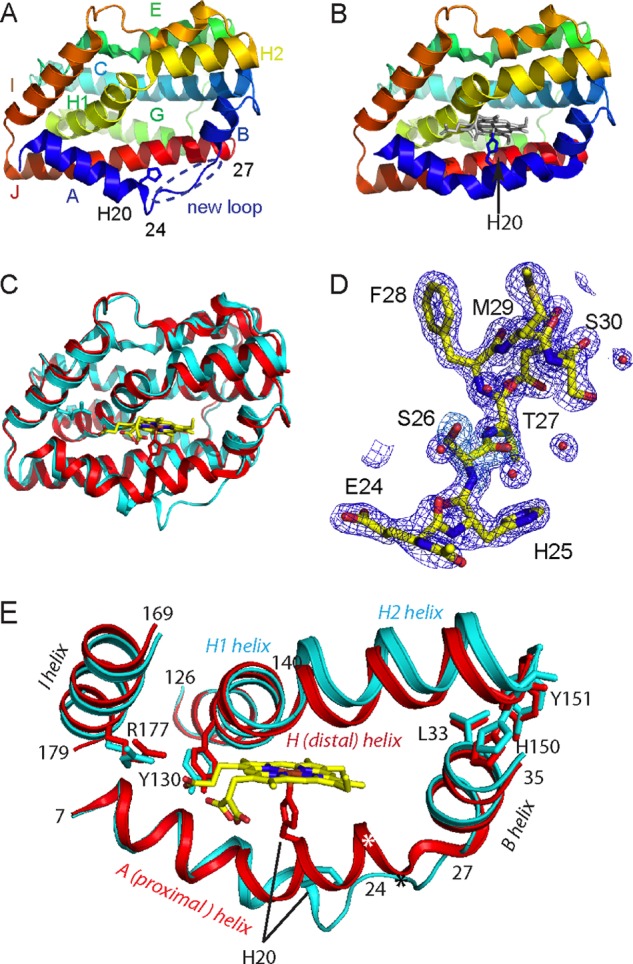

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of the heme pockets of the substrate-free HmuO to that of the ferric heme-HmuO complex. A and B, ribbon diagrams of the vicinity of the heme pocket of the substrate-free HmuO (A) and the ferric heme-HmuO complex (B). C, superposition of the heme-binding site of the substrate-free HmuO and the ferric heme-HmuO complex. For both structures, the nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and iron atoms are colored in blue, red, ochre, and orange, respectively. The carbon atoms of the heme-HmuO complex and those of the substrate-free HmuO are colored in yellow and cyan, respectively. D, superposition of the distal heme pockets of the substrate-free HmuO and the ferric heme-HmuO complex. The same color scheme as C is used except for the water oxygen atoms that are colored in red for the heme complex and green for the substrate-free form. These figures were prepared with PyMOL (44).

The second notable structural difference is found in the C-terminal half of the distal helix (Ser-138–His-150), which shifts upward in the substrate-free HmuO compared with the heme complex (Fig. 1E). This shift is due to the partially unfolded proximal helix described above. Unwinding the part of the proximal helix moves B helix (Figs. 1E and 2C, residues 28–35). The backbone of Leu-32, Leu-33, and Gly-35 in B helix interacts with the aromatic side chains of His-150 and Tyr-151 of the C-terminal half of the distal helix (Figs. 1E and 2C). Through these hydrophobic interactions, the movement of the B helix propagates so as to shift the C-terminal half of the distal helix upward in the substrate-free HmuO. This upward move extends the Gly-rich kinked portion of the distal helix in the heme complex to a random coil in the substrate-free form due to the flexible sequence of 135GDLSGG140 conserved in both mammalian and bacterial HO (Fig. 1E). One single kinked distal helix (H helix) in the heme complex becomes two helices, denoted as H1 and H2, connected by a short segment of random coil (Lys-137–Gly-140) in the substrate-free form (Fig. 1E). As a consequence of the partially unfolded proximal helix and upward move and extension of a part of the distal helix, the substrate-free HmuO has a widely opened entrance of the heme pocket, which could facilitate binding of the substrate heme.

In contrast to the C-terminal half of the proximal and distal helices, the conformations of the N-terminal half of these helices are mostly unchanged (Fig. 1, C and E). The I helix is mostly unchanged as well. This region includes Tyr-130 and Arg-177, two residues critical for proper heme seating required for regioselective heme degradation, by forming salt bridge interactions with a propionate of the heme group (18, 22). The aforementioned extension of the distal helix enables HmuO to widen the entrance of the heme pocket without relocating Tyr-130 and Arg-177.

Third, side chain conformations of Arg-132 and Asn-204, two residues located in the heme pocket, are different from those of the heme complex (Fig. 2, A and B). In the heme complex, these side chains point away from the heme pocket. Hydrogen bonding interactions are present between Oδ of Asn-204 and Nη1 of Arg-132 and between Nδ of Asn-204 and OH of Tyr-109 with distances of 2.9 and 2.8 Å, respectively. These interactions are absent in the substrate-free HmuO. The altered side chain orientation of Arg-132 and Asn-204 likely makes the heme pocket more flexible in the substrate-free form.

The fourth notable difference is the number and spatial arrangement of water molecules located in the heme pocket, as depicted in Fig. 2D. In the heme complex, the distal pocket water molecules form an extended hydrogen bond network that provides the protons required for oxygen activation (18, 26). The hydrogen bond network is disrupted in the substrate-free form, although water molecules are present in the heme-binding site. A water molecule, W1′, of the substrate-free HmuO is found at a position close to the coordinated water molecule, W1, in the heme complex, when main chain atoms are superimposed to minimize the r.m.s. deviation. Other water molecules of the distal hydrogen bond network in the heme complex (W2 to W5, Fig. 2D) are displaced in the substrate-free form and do not form the rigid hydrogen bond network. W5 found in the ferric heme-HmuO complex is expelled by glycerol, one of the components of the crystallization solution. The rearrangement of the water molecules is probably caused by the conformational changes of Arg-132 and Asn-204. Arg-132 forms a hydrogen bond with W4′, which forms a hydrogen bond with W2′, which is further hydrogen bonded with W1′. Asn-204 forms a hydrogen bond with a water molecule, which is not found in the heme complex. The distal hydrogen bond network critical for heme degradation is apparently constructed upon heme binding.

MD Simulations

MD simulations were performed to get further insight into the protein conformational changes associated with heme binding and dissociation. Because the available force-fields cannot adequately describe the formation of the heme-His coordination bond, we have monitored the conformational changes taking place upon removing the heme group from the heme-HmuO complex (it is to be expected that similar conformational changes take place upon heme binding). In fact, a previous analysis of rat HO-1 identified several normal modes of the bare protein (without solvent) that connect the heme-bound closed form with the heme-free open form (50). It was pointed out that MD simulations are required to investigate the protein conformational preferences. Here, we perform MD simulations to assess whether the protein evolves toward the open structure observed for the crystal structure of the substrate-free form of HmuO, as well as describing the conformational changes taking place. At the same time, the simulations should probe the helix-to-coil transition taking place upon biliverdin release that is inferred from the crystallographic analysis.

The MD simulations show that the overall structure of the HmuO protein does not change significantly upon removing the heme group. This is reflected in the value of the backbone r.m.s. deviation, which is not very high (1.58 Å). However, we do observe large changes in certain parts of the protein (Fig. 3A). For instance, the r.m.s. deviation of the proximal helix (residues from Gln-18 to Met-29) is 2.54 Å, which is indicative of a high flexibility in this region of the protein. Similar values are found for the distal helix. In fact, these two helices are found to be as flexible as a loop.

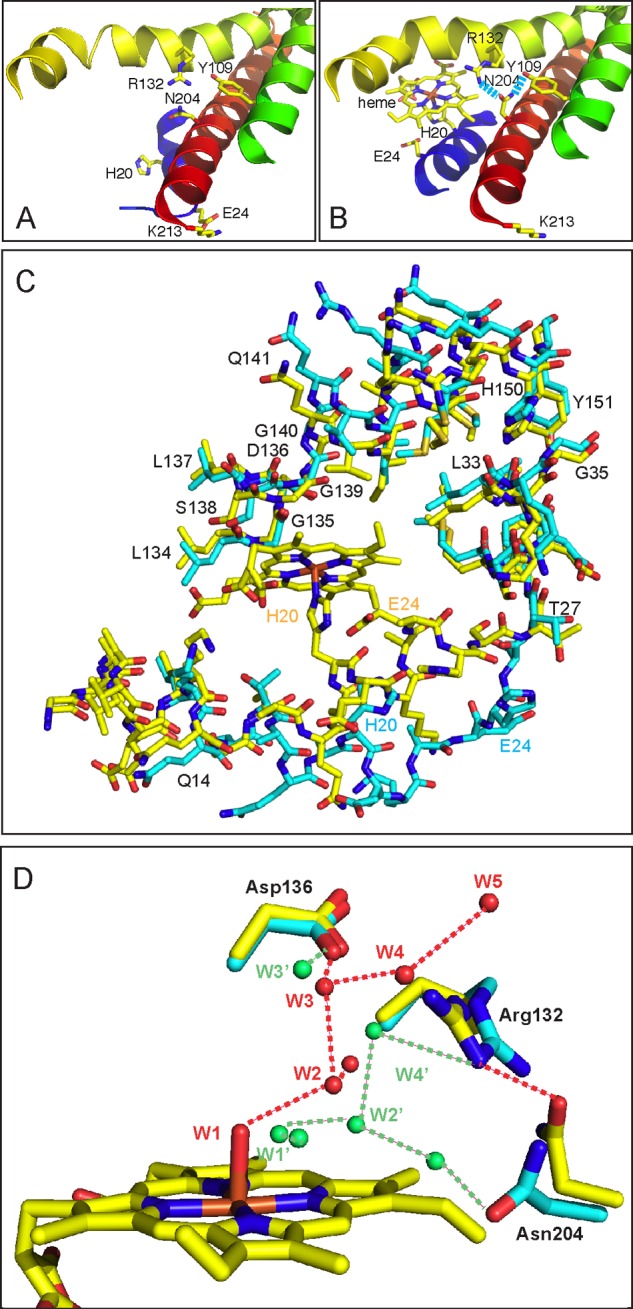

FIGURE 3.

A, estimated r.m.s. deviation per residue from the MD trajectory; B, time dependence of the value of α-RMSD versus time. B, red line is the calculated value for the crystal structure of the heme-HmuO complex. The green line is the value calculated for the crystal structure of the substrate-free form of HmuO, and the blue line is the molecular dynamics structure. A running average of each 100 data values is taken. C, comparison between the backbone of the crystallographic substrate-free (green), the heme-bound complex (red), and a representative snapshot of the molecular dynamics simulation during the 45–55-ns time window (blue). D, time dependence of the value of α-RMSD versus time for the substrate-free form of HmuO.

Fig. 3B shows the time evolution of the α-RMSD collective variable of the proximal helix, which measures its departure from an ideal α-helix (see under “Experimental Procedures”). During the first 50 ns, the α-RMSD is lower than its value in heme-bound structure (α-RMSD = 6.4). However, it occasionally decreases to values close to the ones measured for the substrate-free crystal structure (α-RMSD = 3.5) in which the proximal helix is partially unfolded, and the binding pocket is more open. The fluctuations observed during the MD simulation thus correspond to changes from the closed to a partially open state. At ≈45 ns, a more pronounced conformational change takes place, corresponding to a clear helix-to-coil transition. Afterward, the proximal helix partially folds again, as indicated by the rise in α-RMSD at ≈53 ns. These results indicate that the complete transition from the closed (i.e. heme-bound HmuO) to the open (i.e. the substrate-free form) forms takes place in a much longer time scale, involving several closed-open oscillations, before the protein reaches the fully open conformation. However, the observed changes, especially those occurring around 45–50 ns, can be taken as a good approximation of the changes taking place during dissociation of the heme group in HmuO.

During the helix-to-coil transition observed in the MD simulation, the Cα of Glu-24 moves ≈12 Å from its position in the substrate-bound form, and the Cα of His-20 shifts by 4.2 Å. These values are very similar to the ones obtained by comparison of the substrate-bound and substrate-free crystal structures (11.2 Å for the movement of Cα of Glu-24 and 4.9 Å for His-20). The partial unfolding of the proximal helix induces a movement of the B helix, which affects the hydrophobic interactions between Leu-33 and the distal helix. As a consequence, the distal helix shifts upwards to a structure very similar to the substrate-free crystal structure (two helices connected by a short coil). The N-terminal half of the distal helix does not move due to the ionic interaction between Glu-11 and Arg-190. Residues Arg-177 and Tyr-130, which are involved in the binding of the heme group, are very flexible and exposed to the solvent, but the side chain of Asn-204 remains buried during the simulation. Overall, the heme pocket becomes much wider, as it is found in the crystal structure of the substrate-free form of the protein, as illustrated in Fig. 3C. As a control calculation, we run 30 ns of MD simulation starting from the crystal structure of the substrate-free form. Unlike the simulation starting from the heme-bound HmuO, the binding pocket does not fluctuate between the open and closed conformations but remains in the open conformation (Fig. 3D). Therefore, the changes observed in the simulation starting from the substrate-bound form (and removing the substrate heme) are indicative of a transition toward the open conformation. The helix-to-coil transition observed in the MD simulation of substrate-free HmuO is shown as supplemental Movie S1.

Structure of the Biliverdin-HmuO Complex

In our refinement of four datasets for the biliverdin complex structure determination, the high resolution structure was obtained from dataset II, the diffraction data from the crystal soaked in 200 mm sodium ascorbate for 19 h. Because the crystals of the biliverdin-HmuO complex were catalytically prepared by in situ heme degradation of the ferric heme complex crystals, three molecules, A, B, and C, exist in the asymmetric unit of the biliverdin complex crystal like the heme complex crystal (18). The overall structure of the biliverdin-HmuO complex is very similar to that of the ferric heme-HmuO complex except for small parts of the distal and proximal helices. The r.m.s. deviation for the Cα atoms is 0.44 Å between molecule A of the biliverdin-HmuO complex and that of the ferric heme-HmuO complex, whereas the r.m.s. deviation for the Cα atoms between molecule A of the biliverdin-HmuO complex and that of the substrate-free HmuO is 1.41 Å.

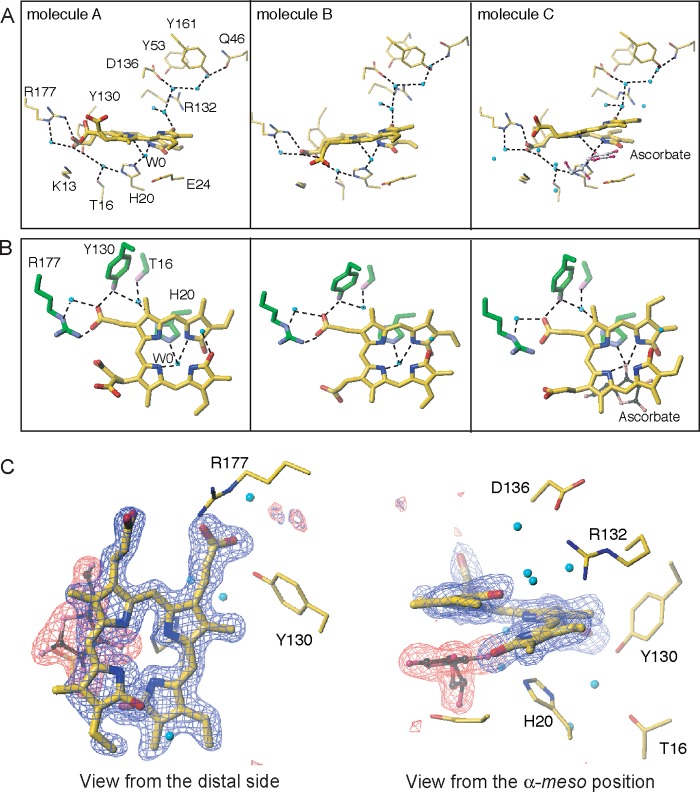

In all molecules in the asymmetric unit, biliverdin is in a helical conformation with the cleavage at the α-meso carbon (Fig. 4). Molecules A and B are similar with respect to the binding site and the conformation of the biliverdin group, whereas molecule C differs from molecules A and B in that ascorbic acid bound to the HmuO protein is discerned as described below. The iron atom is absent, and a water molecule, W0, is found near the biliverdin moiety in molecules A and B. The position of W0 is out of the center of the biliverdin framework toward the proximal His-20 by ∼1.8 Å. In molecules A and B, W0 forms hydrogen bonds with two biliverdin pyrrole nitrogen atoms with distances of 2.9–3.1 Å, but other two pyrrole nitrogen atoms are too far to form a favorable hydrogen bond (3.2–3.8 Å). W0 also forms a hydrogen bond with His-20 Nϵ with a distance of ∼2.8 Å, and His-20 Nδ forms a hydrogen bond with another water molecule, which also forms two hydrogen bonds with the side chain OH groups of Thr-16 and Tyr-130 (Fig. 4, A and B). Probably because of these hydrogen bonds, His-20, the axial heme ligand in the heme complex, is tilted by 15° and rotates about the Cβ-Cγ axis by ∼130° with respect to that of the ferric heme complex. One propionate of the biliverdin is fixed by a salt bridge with Arg-177 and hydrogen bonds with a water molecule and Tyr-130 OH. The other propionate, exposed to solvent and not bound with any residue, is disordered and makes the exposed half of the biliverdin perturbed in molecules A and B. In molecule C, an ascorbate molecule instead of W0 is found and sustains the exposed side of the biliverdin; thus, all non-hydrogen atoms composing biliverdin are placed with high accuracy in the clear electron density map, as shown in Fig. 4C.

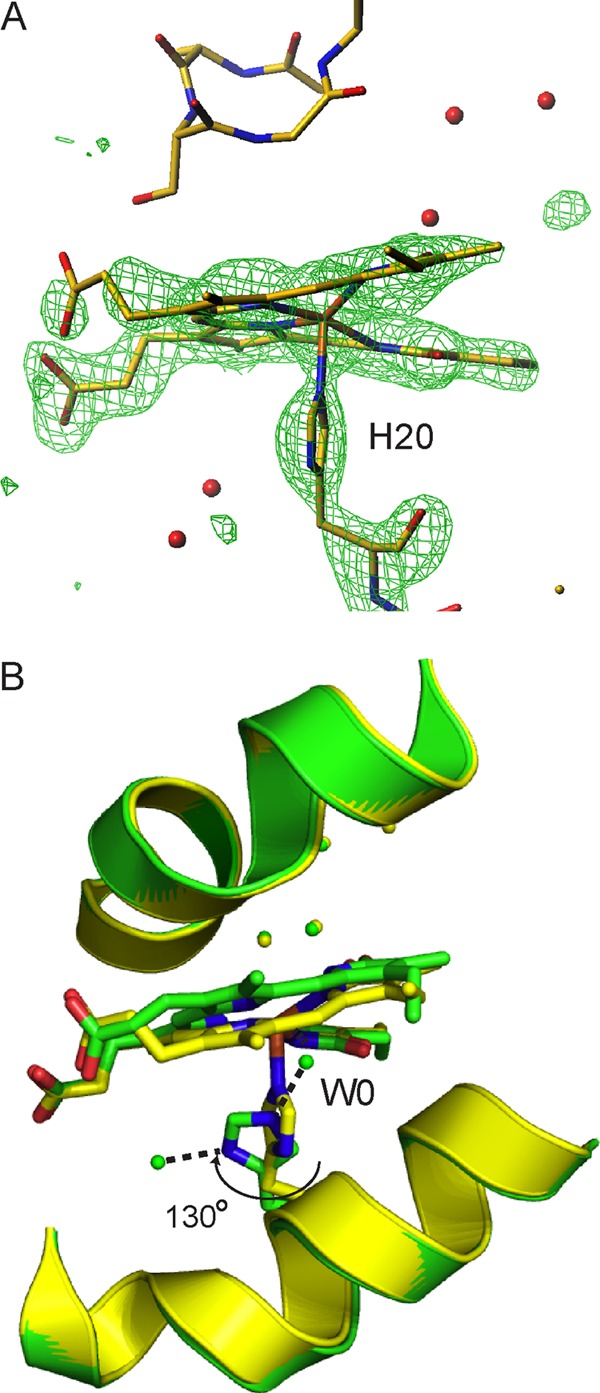

FIGURE 4.

Close-up view of the biliverdin-binding sites in the biliverdin-HmuO complex. A, distal heme pocket water hydrogen bond network and significant residues. Molecules A, B, and C are depicted from left to right. In molecule C, the ascorbate molecule (gray for carbon atoms and magenta for oxygen atoms) is found between the biliverdin and His-20. B, close-up view of the biliverdin-binding site viewed from the distal side. The nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon atoms of the HmuO protein are colored in purple, pink, and green, respectively. The biliverdin molecules are shown in blue, red, and yellow for the nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon atoms, respectively. All water molecules are colored in cyan. C, simulated annealed omit Fo − Fc maps for biliverdin (blue cage) and ascorbate (red cage) in molecule C at the 3.7 σ level viewed from two directions. The figures were prepared with Turbo-Frodo (39).

In the biliverdin-HmuO complex structure, the proximal helix is shifted away from the heme pocket in a manner similar to what is seen in the substrate-free form, albeit to a smaller extent, and retains its secondary structure unlike the substrate-free form. The distal helix of the biliverdin-HmuO complex slightly shifts closer to the active site than that in the substrate-free HmuO. The distal pocket water hydrogen bonding network extended from the heme group to the molecular surface, which is found in the heme complex, is retained in the biliverdin-HmuO complex except for the heme iron ligand water, W1, which is missing in the biliverdin complex structure. A lactam oxygen atom of biliverdin forms a hydrogen bond with a distal pocket water molecule, which is a part of the distal pocket hydrogen bond network. Lack of the heme-proximal His coordination bond and the relaxed proximal and distal helices certainly make biliverdin HmuO interaction much weaker than that in the heme HmuO interaction. This absence of strong electrostatic interactions facilitates biliverdin release from HmuO.

Comparison of the Biliverdin-HmuO with Mammalian Biliverdin-HO-1

The crystal structure of the biliverdin-HmuO complex shows that the biliverdin group is located in the heme pocket and that the iron does not have to be present for biliverdin to maintain a helical conformation in HmuO. These results drastically differ from those found in the structure of the biliverdin complex of human HO-1 (Protein Data Bank code 1S8C (31)), in which the biliverdin adopts an extended twisted conformation and moves into an internal cavity (Fig. 5, A and B). The corresponding internal cavity in the biliverdin-HmuO complex is filled with water molecules composing a rigid hydrogen bond network. In the biliverdin-human HO-1 complex, the pyrrole A lactam oxygen atom is close enough to Asn-210 to accept the hydrogen bond, whereas Asn-204 of HmuO, corresponding to Asn-210 of HO-1, does not interact with the biliverdin but does with Arg-132 as is the case for the heme-HmuO complex.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of the biliverdin structures. A, biliverdin complex of HmuO (left panel) is compared with that of human HO-1 (right panel) (PDB 1S8C (31)). B, overlay of the biliverdin groups reported for free biliverdin dimethyl ester in magenta (32), biliverdin in apoMb in cyan (33), biliverdin in HmuO in green (this work), and biliverdin in human HO-1 in yellow (31). The figures were prepared with PyMOL (44).

Reasons for the differences in conformation and location of the bound biliverdin are not apparent, but two plausible reasons emerge. One is the difference in the size of the internal cavity. The internal cavity in HO-1 is larger than that in HmuO (18, 20), which could accommodate biliverdin in the twisted extended conformation. In the light of the all-Z-all-syn-type helical structures reported for free biliverdin (32) and the biliverdin complexes with apo-myoglobin and biliverdin IXβ reductase (Fig. 5B) (33, 34), some structural aspects of HO-1, the large internal cavity in particular, must be responsible for biliverdin in HO-1 to assume an atypical extended structure. Indeed, Poulos and co-workers (31) have suggested that the large hydrophobic cavity of HO-1 serves as a temporary site where biliverdin loosely binds before biliverdin reductase binding to HO-1. HO-2 has a large hydrophobic cavity as HO-1 (51), and structures of the biliverdin complexes of HO-2 and other bacterial HO would resolve these differences. The other possible reason is the preparation method of the biliverdin complex crystals; the HO-1 crystals were grown from the biliverdin complex solutions (31), and the crystals of the biliverdin-HmuO complex were obtained by in situ ascorbate-driven HO catalytic reactions in the crystals of the heme-HmuO complex.

Another difference is the absence of the catalytically critical water hydrogen bond network in the human biliverdin-HO-1 structure, where the key catalytic groups in the distal pocket, including the conserved Asp residue, are reported to remain unchanged with respect to the heme-HO-1 complex (31). As described above, the hydrogen bond network is present in the biliverdin-HmuO structure. 1H NMR characterization has found significantly greater dynamic stability of the hydrogen bond network in the heme complex of HmuO than that of human HO-1 (52). This might account in part for the presence of the hydrogen bond network in the HmuO complex, and its absence in the HO-1 complex is probably due to the extended conformation and different binding location of biliverdin.

Structure of the Fe3+-Biliverdin-HmuO Complex

In the HO-catalyzed heme degradation reaction, biliverdin is formed upon one electron-reduction of the Fe3+-biliverdin complex (27). During the course of our crystallographic studies, we have successfully arrested the HO reaction at the Fe3+-biliverdin complex stage in crystals. The electron density map of molecule A from dataset III, the diffraction data from the crystal incubated with 200 mm ascorbate for 9 h, shows a large electron density at the center of the biliverdin group (Fig. 6A), indicating molecule A is trapped as the Fe3+-biliverdin-HmuO complex. The overall structure of the Fe3+-biliverdin-HmuO is very similar to that of the biliverdin complex. The r.m.s. deviation for the Cα atoms is only 0.18 Å between them. Release of iron from the biliverdin moiety does not change the positions of the distal pocket water molecules composing the rigid hydrogen bond network (Fig. 6B). Like iron-free biliverdin, Fe3+-biliverdin is in a helical conformation. The distance between the two lactam oxygen atoms is 2.7 Å, which is shorter than that of ∼3.3 Å in the biliverdin complex, indicating that the distortion of the biliverdin framework of the Fe3+ complex is smaller than that of the iron-free biliverdin because of iron coordination (Fig. 6B). Compared with the heme complex, the proximal helix is shifted away from the heme pocket in a manner similar to what is seen in the iron-free biliverdin complex. The Fe3+ in the complex is five-coordinate as reported for the Fe3+-biliverdin rat HO-1 structure (53). The distance between Fe3+ and Nϵ of the proximal ligand, His-20, is 2.2 Å, which is slightly longer than that of 2.0 Å in the ferric heme complex. The orientation of His-20 is similar to that of the heme complex, but the distorted electron density for His-20 indicates that it has small oscillation around its Cβ-Cγ axis (Fig. 6A). The Fe-Npyrrole distances are ∼2.06 Å for pyrroles A and C and ∼2.34 Å for pyrroles B and D, respectively. The iron atom is located in an asymmetric coordination environment, consistent with a highly anisotropic high spin EPR spectrum of the complex (54).

FIGURE 6.

Structure of the Fe3+-biliverdin complex and comparison with that of the biliverdin complex. A, omit map of the Fe3+-biliverdin group and His-20 countered at the 3.0 σ level are illustrated by an overlay onto the Fe3+-biliverdin and His-20 structures. The distal residues and nearby water molecules are also included. B, superimposition of the Fe3+-biliverdin HmuO (yellow) and the biliverdin-HmuO (green) complexes. In the biliverdin complex model, the carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms of His-20 and biliverdin are shown in green, blue, and red, respectively, and water molecules are in green. In the Fe3+-biliverdin complex model, the carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and iron atoms of His-20 and Fe3+-biliverdin are shown in yellow, blue, red, and orange, respectively, and water molecules are in yellow. These figures were prepared with Turbo-Frodo (39) for A and with PyMOL (44) for B.

Two Intermediates during Iron Release

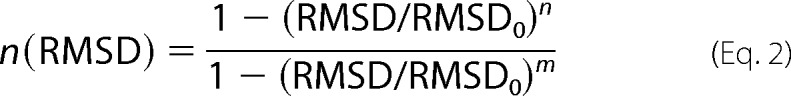

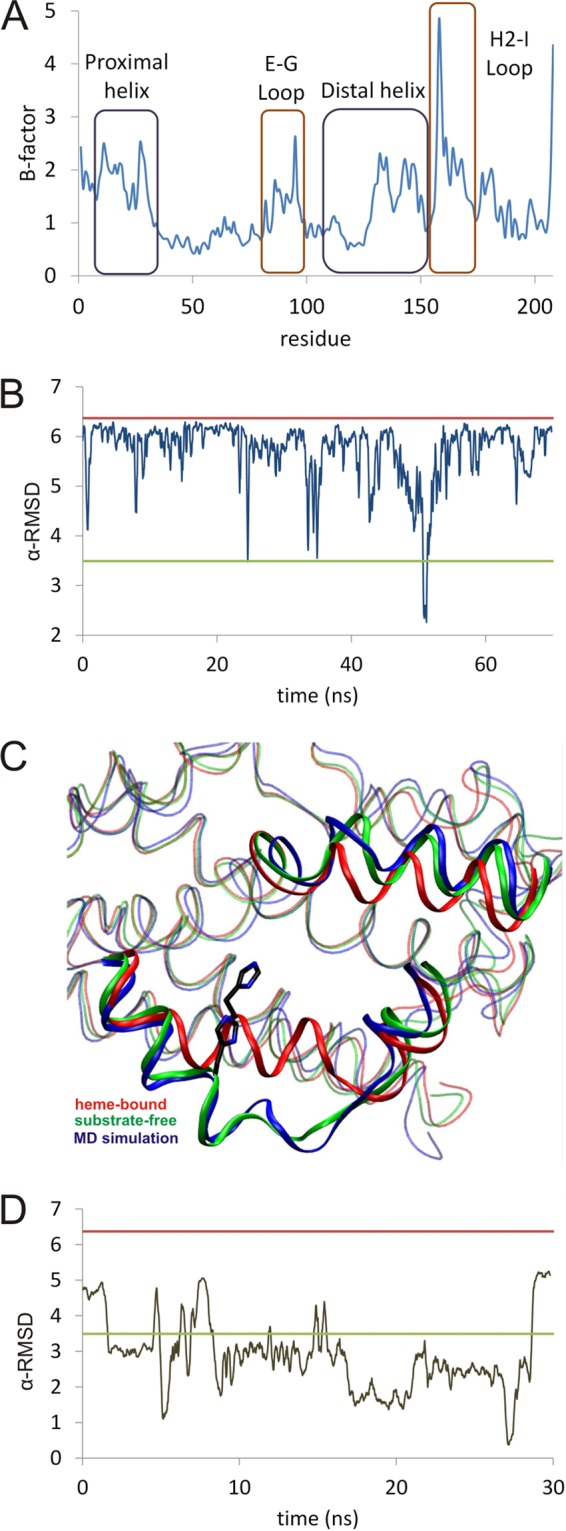

Dataset IV was first refined to 1.70 Å resolution as the biliverdin-HmuO complex. However, the electron density indicates that it contains two intermediates between the Fe3+-biliverdin-HmuO and the biliverdin-HmuO complexes, as described below.

The overall structures of the three molecules in the asymmetric units are very similar, as demonstrated by the small r.m.s. differences among their Cα atoms (0.35–0.43 Å). Molecule B is likely to correspond to the biliverdin-HmuO complex; however, residual electron density appears in the biliverdin framework for molecules A and C at the same position as the Fe3+ atom in the Fe3+-biliverdin complex (Fig. 7A for molecule A). This residual electron density is best interpreted as an iron atom with the refined occupancy of 0.3 in the Fo − Fc map, because the atom is positioned close to the pyrrole nitrogen atoms as seen in the Fe3+-biliverdin-HmuO complex. The distal pocket water molecules found in the biliverdin-HmuO and Fe3+-biliverdin complexes (Figs. 4 and 6) are also present with full occupancy. About 2.2 Å above the iron, further electron density with refined occupancy of 0.3, assignable to residual water, is found. This feature is absent in the Fe3+-biliverdin complex structure. His-20 assumes only one conformation, which is very similar to that found in the biliverdin complex. The distance between the iron atom and Nϵ of His-20 (3.7 Å) is too long for a Fe-His coordination bond. Overall, these results indicate that the structures associated with molecules A and C from dataset IV do not fully correspond to the Fe3+-biliverdin-HmuO complex. The water molecule, W0, that links the biliverdin pyrrole nitrogen to His-20 Nϵ in the biliverdin complex (Fig. 4, A and B) is absent in dataset IV molecules A and C structures, demonstrating that they do not contain the biliverdin-HmuO complex either. The structure is best represented as a 30:70 mixture of two species; one has iron-biliverdin, and the other has biliverdin in the HmuO protein structure very similar to that of the biliverdin complex.

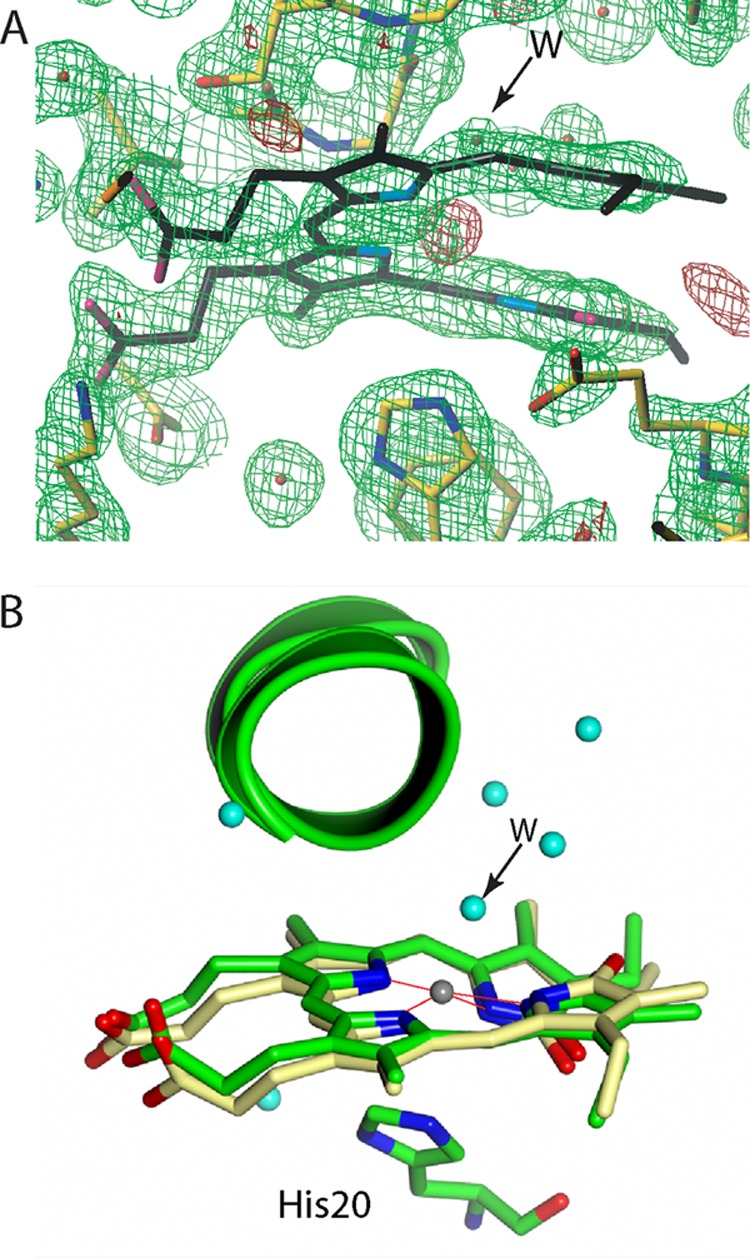

FIGURE 7.

Vicinity of biliverdin in the intermediate states. A, electron density maps of a mixture of the intermediates during the iron release for molecule A drawn with Turbo-Frodo (39). Shown are the 2Fo − Fc (green cage) and Fo − Fc (red cage) maps at the 1.0 and 4.0 σ levels, respectively. The residual Fo − Fc density (red cage) located centrally in the biliverdin framework can be interpreted as Fe2+, which is not modeled in this structure. The axial His-20 is in 100% occupancy and is too far from the iron atom for a coordination bond. B, structure of the biliverdin vicinity for molecule A drawn with PyMOL (44). For His-20 and biliverdin, the carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are shown in light green, blue, and red, respectively. For iron-biliverdin, the carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and iron atoms are shown in yellow, blue, red, and gray, respectively. Water molecules are shown in cyan. A water molecule with 30% occupancy is labeled as W with an arrow.

In the minor population intermediate (∼30% of the population in this structure), the iron atom is retained in the biliverdin framework like in the Fe3+-biliverdin complex. However, the iron-proximal His bond is broken, and His-20 adopts a conformation very similar to that found in the iron-free biliverdin-HmuO complex. A water molecule with a refined B factor of 16 Å2 is located at about 2.2 Å from the iron atom, a distance suitable for a coordination bond, suggesting the possibility that this water molecule is an axial iron ligand. The relatively small B factor value is consistent with the observation that the water molecule not only binds to iron but also forms hydrogen bonds with an adjacent water molecule and the carbonyl oxygen atom of Gly-135. In the major population intermediate (∼70% population), iron is absent in the biliverdin framework, as is the case for the biliverdin-HmuO complex, but W0 found in the biliverdin-HmuO complex is not present. The structure model of the mixture is shown in Fig. 7B for molecule A.

DISCUSSION

The structures of the substrate-free and the product-bound forms of HmuO, which are determined at the higher resolution with lower R factors than those reported previously for mammalian HO-1 and HO-2, the MD simulations of the heme release from HmuO, and the structures of two intermediates between the Fe3+-biliverdin-HmuO and the biliverdin-HmuO complexes make it possible to delineate HmuO protein structural changes and provide new insight into the substrate binding and the product release by HO.

Substrate-free HmuO Structure and Its Implication for the Heme Binding Mechanism

One of the noticeable structural features of substrate-free HmuO is the partially unfolded proximal helix (Fig. 1, A and D). Molecular dynamic simulation verifies the crystal structure of the substrate-free form of HmuO (Fig. 3C). There are precedents for the substrate binding-induced coil-to-helix transition reported in the literature. One example is human cytosolic NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase, in which the substrate (and metal ion) binding induces “loop to α-helix transition” forming the active site structure (55). The loop conformation is postulated to be energetically more stable than the α-helical conformation in the absence of the substrate. This is apparently also the case for HmuO, in which the partially unfolded conformation of the proximal helix becomes more stable in the absence of the substrate heme group. Heme binding-induced coil-to-helix transition has been reported recently for Lactococcus lactis heme-regulated transcriptional regulator (HrtR) (56). Heme binding to HrtR converts a short loop between two helices into a helix forming one long helix that causes structural changes in the HrtR protein, resulting in dissociation from the target DNA.

Although mechanisms by which heme is acquired and transferred to HmuO in C. diphtheriae have yet to be elucidated, HmuTUV has been identified as its heme transporter system (57). A current model of heme transport in C. diphtheriae presumes that HtaA, an iron-regulated heme-binding protein, first captures an extracellular heme, which is then transferred to HmuU, a membrane-bound permease, via HtaB and HmuT. HmuU, together with HmuV, an ATPase, transits heme through the cell membrane into the bacterial cytosol where HmuO binds and degrades the intercellular heme, leading to liberation of the heme-bound iron (58). In the case of P. aeruginosa, its heme oxygenase, PigA, forms a complex with a cytoplasmic heme-binding protein, PhuS, and heme is transferred within the complex without being released into media (59, 60). Such a cytoplasmic heme-binding protein has not been identified in C. diphtheriae, and direct heme binding to HmuO has been postulated (57, 58). Based on this notion, a possible scenario for heme binding to HmuO is proposed as below (Fig. 8A).

FIGURE 8.

Proposed mechanism of the heme binding. A, proposed mechanism of heme binding to HmuO. B, stereo diagram of the boundary region of the proximal helix and new loop in the substrate-free HmuO. C, same region of the ferric-heme-HmuO complex. These figures were prepared with BOBSCRIPT (42) and Raster3D (43).

The substrate-free HmuO has a flexible wide opening pocket to facilitate heme binding. Arg-177 (and probably Tyr-130) captures one of the heme propionates in the correct position and orientation. His-20 then (or simultaneously) moves to bind to the heme iron. His-20 binding to the heme iron induces the conformational changes of the residues in its neighborhood, including Ala-17, Gln-18, Ala-19, Glu-21, Lys-22, Ala-23, and Glu-24. The Oϵ of Glu-24 forms a salt bridge with Nξ of Lys-213 in the substrate-free form. Because of these conformational changes, the distance between Glu-24 Oϵ and Lys-213 Nξ extends, and the salt bridge is broken. The released side chain of Glu-24 is flipped, and its Oϵ atom forms a hydrogen bond with Nδ of His-20 (Fig. 8, B and C). Then, the carbonyl oxygen of His-20 forms the hydrogen bond with amide nitrogen of Glu-24, and the “new loop” is consequently changed to an α-helix (Fig. 8, B and C). These hydrogen and coordination bonds make the proximal helix concaved (Fig. 8A). The rolled proximal helix pulls B helix, and the C-terminal half of the distal helix is pulled down through the interactions between Leu-32, Leu-33, and Gly-35 of the B helix and His-150 and Tyr-151 of the C terminus of the distal helix. This downward move changes the random coil (Lys-137–Gly-140) of substrate-free HmuO to a kinked portion due to the Gly-rich flexible sequence, resulting in formation of a single kinked distal helix (H helix). These conformational changes of the helices close the heme pocket. Additionally, the side chain of Asn-204 is pushed away from the pocket by the heme group and forms two new hydrogen bonds with Tyr-109 and Arg-132 (Fig. 2, A and B). The new hydrogen bonds help to stabilize the heme pocket structure. The conformational changes of Arg-132 and Asn-204 also induce rearrangement of the distal pocket water molecules so as to form the catalytically critical hydrogen bond network (Fig. 2D). The mechanism of heme binding is shown in supplemental Movie S2, based on the crystal structures of the substrate-free and the heme-bound forms and the MD simulations.

This proposed mechanism has three new aspects of heme binding by HO. First, the proximal helix is partially unfolded to open the heme pocket and to relax the overall structure in the substrate-free form. In the 2.55-Å resolution crystal structure of the substrate-free form of rat HO-1, the proximal helix was not visible, which the authors attributed to fluctuation (29). Similarly, in the crystal structure of the substrate-free human HO-1, the averaged B factors of the proximal helix, especially in molecules C and D, were very high for a 2.1-Å resolution structure (30). Although the structural features of the substrate-free HmuO are not exactly the same as those reported for the mammalian counterparts, the high flexibility is the common property of the substrate-free forms of HO proteins. Second, Gln-38, which was proposed to contribute to stabilization of the heme pocket structure by forming hydrogen bonds with Glu-29 in the mammalian HO-1 (29, 30), is absent in HmuO. Instead, the two hydrogen bonds of Asn-204 with Tyr-109 and Arg-132 play a role in the heme pocket structure stabilization in HmuO. Third, the distal pocket water hydrogen bond network is formed upon heme binding. This network is realized by the conformational changes of Asn-204 and Arg-132 associated with the heme binding to HmuO. Formation of the catalytically critical distal pocket solvent hydrogen bond network has not been addressed in the previous substrate-free mammalian HO-1 and -2 studies probably due to difficulties in identifying water molecules in the lower resolution mammalian HO structures (29–30, 51).

Implication for Iron Release from the Fe3+-Biliverdin Complex

The structures of molecules A and C from dataset IV (Fig. 7) are considered as a mixture of two intermediates between the Fe3+-biliverdin and biliverdin complexes and would provide structural information relevant to iron release from the biliverdin framework.

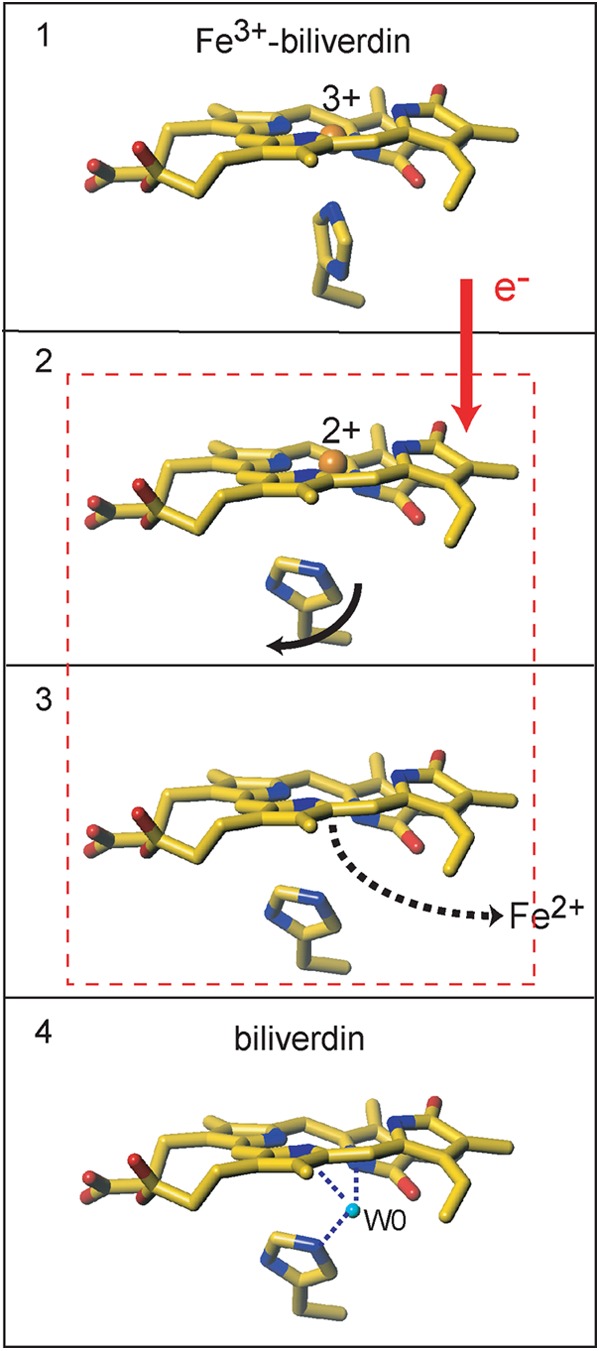

The 30% population intermediate has the iron-biliverdin framework without the iron-proximal His bond. This state, named state 2 in Fig. 9, is likely to be generated right after the reduction of the Fe3+-biliverdin complex. A water molecule apparently coordinates to the biliverdin iron. To our knowledge, there is no precedent for a ferrous heme protein with a water axial ligand, except for cases realized by cryo-radiolytic reduction of six-coordinate heme proteins, such as cryo-reduced metmyoglobin (61). X-ray absorption spectroscopy will be utilized to assess the iron coordination structure and the valence state of this intermediate in future studies. The ∼70% population intermediate structure is very similar to that of the biliverdin complex, but the W0 found in the structure of the biliverdin-HmuO complex has yet to be incorporated. Absence of iron and W0 makes this structure assignable to a state after the minor population intermediate described above but before the generation of the final product biliverdin, depicted as state 3 in Fig. 9. The room created by the rotation and movement of His-20 (state 3) is likely to serve as a route for iron release in this stage. This room is eventually filled by a water molecule (W0) that would stabilize the biliverdin moiety in the heme pocket after the iron release.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic representation of the iron release from the Fe3+-biliverdin complex. State 1, the Fe3+-biliverdin complex. State 2, the structure of a minor component where iron is presumably reduced and the proximal His assumes the same conformation as that in the biliverdin complex. State 3, the structure of the major component where iron is removed from the biliverdin framework but W0 is not yet incorporated in the heme pocket. State 4, the biliverdin-HmuO complex. A mixture of two intermediates shown in states 2 and 3 represents the structure of molecules A and C from dataset IV (Fig. 7). This figure was prepared with Turbo-Frodo (39).

HmuO Structural Changes after Release of Biliverdin

In mammalian HO-dependent heme degradation systems, biliverdin is reduced to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase, which binds to mammalian HO and facilitates biliverdin release from the HO protein (62, 63). Bacterial homologues of mammalian biliverdin reductase have not been identified, and fates of bacterial biliverdin remain unclear (8). Nevertheless, structural information for the biliverdin-HmuO complex, and the substrate-free HmuO, together with the MD simulations, allows us to consider the structural changes in HmuO after biliverdin is released. In the biliverdin complex, His-20 is not fully liberated due to its hydrogen bonding interactions (Fig. 4A), resulting in slight relaxation of the proximal helix. After biliverdin release, His-20, which interacts with the biliverdin group in the biliverdin complex, would change its conformation. Liberation of His-20 causes further relaxation of the proximal helix, as confirmed by the MD simulations, and the distorted proximal helix changes conformation to a short straight helix. The C terminus of the proximal helix would then evolve to a loop (new loop in Fig. 1A), as it is found in the substrate-free HmuO. Consequently, the distal and B helices separate each other (Fig. 1), causing Asn-204 and Arg-132 to move toward the open heme pocket. These events synergistically cause relaxation of the heme pocket, leading to a wide open heme pocket in the substrate-free HmuO. The supplemental Movie S3 depicts the HmuO structural changes from the Fe3+-biliverdin complex to the product release.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Y. Shiro and the members of BL44B2 and BL38B1 at SPring-8 and the members of BL5A and NW12A at the Photon Factory for their help in intensity data collection. We thank Dr. C. S. Raman of the University of Maryland for comments. We acknowledge the computer support, technical expertise, and assistance provided by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center-Centro Nacional de Supercomputación. X-ray diffraction experiments were conducted under the approval of 2003G118 at the Photon Factory and 2005A005-NL1-np at BL38B1 of SPring-8.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research 21350087, 2412006, and 24350081 (to M. I.-S.) and 18770080, 22770096, and 24570122 (to M. U.) from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science, the Management Expenses Grant for National Universities Corporations from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness Grant CTQ2011-25871, and Generalitat de Catalunya Grant 2009SGR-1309.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

This article contains supplemental Movies S1–S3.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4GOH, 4GPC, 4GPF, and 4GPH) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

By definition, HO is not a heme protein by itself. In early reports, the HO proteins free from substrate heme have been termed as apo-HO in an analogy to myoglobin and hemoglobin. For the sake of proper nomenclature, we use the substrate-free HO and substrate-free HmuO for HO and HmuO devoid of the substrate heme group, respectively.

- HO

- heme oxygenase

- HmuO

- HO from Corynebacterium diphtheriae

- HO-1

- an inducible isozyme of mammalian heme oxygenase

- HO-2

- a constitutive isozyme of mammalian heme oxygenase

- heme

- iron protoporphyrin IX

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- r.m.s.

- root mean square.

REFERENCES

- 1. Maines M. D. (1997) The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 37, 517–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schacter B. A., Nelson E. B., Marver H. S., Masters B. S. (1972) Immunochemical evidence for an association of heme oxygenase with the microsomal electron transport system. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 3601–3607 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Poss K. D., Tonegawa S. (1997) Heme oxygenase 1 is required for mammalian iron reutilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10919–10924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boehning D., Snyder S. H. (2003) Novel neural modulators. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26, 105–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paul B. D., Snyder S. H. (2012) H2S signaling through protein sulfhydration and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colas C., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2003) Autocatalytic radical reactions in physiological prosthetic heme modification. Chem. Rev. 103, 2305–2332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wilks A., Burkhard K. A. (2007) Heme and virulence: How bacterial pathogens regulate, transport, and utilize heme. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 511–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anzaldi L. L., Skaar E. P. (2010) Overcoming the heme paradox: Heme toxicity and tolerance in bacterial pathogens. Infect. Immun. 78, 4977–4989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reniere M. L., Ukpabi G. N., Harry S. R., Stec D. F., Krull R., Wright D. W., Bachmann B. O., Murphy M. E., Skaar E. P. (2010) The IsdG-family of haem oxygenases degrades haem to a novel chromophore. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1529–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nambu S., Matsui T., Goulding C. W., Takahashi S., Ikeda-Saito M. (2013) A new way to degrade heme: The Mycobacterium tuberculosis enzyme MhuD catalyzes heme degradation without generating CO. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10101–10109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsui T., Nambu S., Ono Y., Goulding C. W., Tsumoto K., Ikeda-Saito M. (2013) Heme degradation by Staphylococcus aureus IsdG and isdI liberates formaldehyde rather than carbon monoxide. Biochemistry 52, 3025–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmitt M. P. (1997) Utilization of host iron sources by Corynebacterium diphtheriae: Identification of a gene whose product is homologous to eukaryotic heme oxygenases and is required for acquisition of iron from heme and hemoglobin. J. Bacteriol. 179, 838–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu W., Wilks A., Stojiljkovic I. (2000) Degradation of heme in Gram-negative bacteria: The product of the hemO gene of Neisseriae is a heme oxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 182, 6783–6790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ratliff M., Zhu W., Deshmukh R., Wilks A., Stojiljkovic I. (2001) Homologues of neisserial heme oxygenase in Gram-negative bacteria: Degradation of heme by the product of the pigA gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6394–6403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilks A., Schmitt M. P. (1998) Expression and characterization of a heme oxygenase (HmuO) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae: Iron acquisition requires oxidative cleavage of the heme macrocycle. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 837–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chu G. C., Katakura K., Zhang X., Yoshida T., Ikeda-Saito M. (1999) Heme degradation as catalyzed by a recombinant bacterial heme oxygenase (HmuO) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21319–21325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schuller D. J., Zhu W., Stojiljkovic I., Wilks A., Poulos T. L. (2001) Crystal structure of heme oxygenase from the Gram-negative pathogen Neisseria meningitidis and a comparison with mammalian heme oxygenase-1. Biochemistry 40, 11552–11558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hirotsu S., Chu G. C., Unno M., Lee D.-S., Yoshida T., Park S.-Y., Shiro Y., Ikeda-Saito M. (2004) The crystal structures of the ferric and ferrous forms of the heme complex of HmuO, a heme oxygenase of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11937–11947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Friedman J., Lad L., Li H., Wilks A., Poulos T. L. (2004) Structural basis for novel δ-regioselective heme oxygenation in opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry 43, 5239–5245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schuller D. J., Wilks A., Ortiz de Montellano P. R., Poulos T. L. (1999) Crystal structure of human heme oxygenase-1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 860–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilks A. (2002) Heme oxygenase: Evolution, structure, and mechanism. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 4, 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Unno M., Matsui T., Ikeda-Saito M. (2007) Structure and catalytic mechanism of heme oxygenase. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 553–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsui T., Unno M., Ikeda-Saito M. (2010) Heme oxygenase reveals its strategy for catalyzing three successive oxygenation reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 240–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsui T., Iwasaki M., Sugiyama R., Unno M., Ikeda-Saito M. (2010) Dioxygen activation for self-degradation of heme: Reaction mechanism and regulation of heme oxygenase. Inorg. Chem. 49, 3602–3609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lai W., Chen H., Matsui T., Omori K., Unno M., Ikeda-Saito M., Shaik S. (2010) Enzymatic ring-opening mechanism of verdoheme by the heme oxygenase: A combined x-ray crystallography and QM/MM study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 12960–12970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Unno M., Matsui T., Chu G. C., Couture M., Yoshida T., Rousseau D. L., Olson J. S., Ikeda-Saito M. (2004) Crystal structure of the dioxygen-bound heme oxygenase from Corynebacterium diphtheriae: Implications for heme oxygenase function. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21055–21061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoshida T., Kikuchi G. (1978) Features of the reaction of heme degradation catalyzed by the reconstituted microsomal heme oxygenase system. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 4230–4236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Unno M., Matsui T., Ikeda-Saito M. (2012) Crystallographic studies of heme oxygenase complexed with an unstable reaction intermediate, verdoheme. J. Inorg. Biochem. 113, 102–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sugishima M., Sakamoto H., Kakuta Y., Omata Y., Hayashi S., Noguchi M., Fukuyama K. (2002) Crystal structure of rat apo-heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1): Mechanism of heme binding in HO-1 inferred from structural comparison of the apo and heme complex forms. Biochemistry 41, 7293–7300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lad L., Schuller D. J., Shimizu H., Friedman J., Li H., Ortiz de Montellano P. R., Poulos T. L. (2003) Comparison of the heme-free and -bound crystal structures of human heme oxygenase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7834–7843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lad L., Friedman J., Li H., Bhaskar B., Ortiz de Montellano P. R., Poulos T. L. (2004) Crystal structure of human heme oxygenase-1 in a complex with biliverdin. Biochemistry 43, 3793–3801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sheldrick W. S. (1976) Crystal and molecular structure of biliverdin dimethyl ester. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 1453–1462 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wagner U.G., Müller N., Schmitzberger W., Falk H., Kratky C. (1995) Structure determination of the biliverdin apomyoglobin complex: Crystal structure analysis of two crystal forms at 1.4 and 1.5 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 247, 326–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pereira P. J., Macedo-Ribeiro S., Párraga A., Pérez-Luque R., Cunningham O., Darcy K., Mantle T. J., Coll M. (2001) Structure of human biliverdin IXβ reductase, an early fetal bilirubin IXβ producing enzyme. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Collaborative Computational Project No. 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jones T. A., Zou J.-Y., Cowan S. E., Kjeldgaard M. (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 47, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jones T. A. (1978) A graphics model building and refinement system for macromolecules. J. Appl. Cryst. 11, 268–272 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schomaker V., Trueblood K. N. (1968) On the rigid-body motion of molecules in crystals. Acta Crystallogr. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 24, 63–76 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Esnouf R. M. (1999) Further additions to MolScript version 1.4, including reading and contouring of electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 938–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Merritt E. A., Bacon D. J. (1997) Raster3D: Photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277, 505–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cornell W. D., Cieplak P., Bayly C. I., Gould I. R., Merz K. M., Ferguson D. M., Spellmeyer D. C., Fox T., Caldwell J. W., Kollman P. A. (1995) A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5179–5197 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pearlman D. A., Case D. A., Caldwell J. W., Ross W. S., Cheatham T. E., III, Debolt S., Ferguson D., Seibel G., Kollman P. A. (1995) AMBER, a package of computer programs for applying molecular mechanics, normal mode analysis, molecular dynamics, and free energy calculations to simulate the structural and energetic properties of molecules. Comput. Phys. Commun. 91, 1–41 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kalé L., Skeel R., Bhandarkar M., Brunner R., Gursoy A., Krawetz N., Phillips J., Shinozaki A., Varadarajan K., Schulten K. (1999) NAMD2: Greater scalability for parallel molecular dynamics. J. Comp. Phys. 151, 283–312 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pietrucci F., Laio A. (2009) A collective variable for the efficient exploration of protein β-sheet structures: Application to SH3 and GB1. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 2197–2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Du Z., Unno M., Matsui T., Ikeda-Saito M., La Mar G. N. (2010) Solution 1H NMR characterization of substrate-free C. diphtheriae heme oxygenase: Pertinence for determining magnetic axes in paramagnetic substrate complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 104, 1063–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Maréchal J.-D., Perahia D. (2008) Use of normal modes for structural modeling of proteins: The case study of rat heme oxygenase 1. Eur. Biophys. J. 37, 1157–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bianchetti C. M., Yi L., Ragsdale S. W., Phillips G. N., Jr. (2007) Comparison of apo- and heme-bound crystal structures of a truncated human heme oxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37624–37631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li Y., Syvitski R. T., Chu G. C., Ikeda-Saito M., Mar G. N. (2003) Solution 1H NMR investigation of the active site molecular and electronic structures of substrate-bound, cyanide-inhibited HmuO, a bacterial heme oxygenase from Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6651–6663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sugishima M., Sakamoto H., Higashimoto Y., Noguchi M., Fukuyama (2003) Crystal structure of rat heme oxygenase-1 in complex with biliverdin-iron chelate: Conformational change of the distal helix during the heme cleavage reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32352–32358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ikeda-Saito M., Fujii H. (2003) in Paramagnetic Resonance of Metallobiomolecules (Tesler J., ed) Vol. 858, pp. 97–112, American Chemical Society, Washington, D. C. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu X., Zhao J., Xu Z., Peng B., Huang Q., Arnold E., Ding J. (2004) Structures of human cytosolic NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase reveal a novel self-regulatory mechanism of activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33946–33957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sawai H., Yamanaka M., Sugimoto H., Shiro Y., Aono S. (2012) Structural basis for the transcriptional regulation of heme homeostasis in Lactococcus lactis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30755–30768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Drazek E. S., Hammack C. A., Schmitt M. P. (2000) Corynebacterium diphtheriae genes required for acquisition of iron from haemin and haemoglobin are homologous to ABC haemin transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 36, 68–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Allen C. E., Schmitt M. P. (2009) HtaA is an iron-regulated hemin binding protein involved in the utilization of heme iron in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J. Bacteriol. 191, 2638–2648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bhakta M. N., Wilks A. (2006) The mechanism of heme transfer from the cytoplasmic heme binding protein PhuS to the δ-regioselective heme oxygenase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry 45, 11642–11649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barker K. D., Barkovits K., Wilks A. (2012) Metabolic flux of extracellular heme uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is driven by the iron-regulated heme oxygenase (HemO). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 18342–18350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Beitlich T., Kühnel K., Schulze-Briese C., Shoeman R. L., Schlichting I. (2007) Cryoradiolytic reduction of crystalline heme proteins: Analysis by UV-Vis spectroscopy and x-ray crystallography. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 14, 11–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu Y., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2000) Reaction intermediates and single turnover rate constants for the oxidation of heme by human heme oxygenase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5297–5307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang J., de Montellano P. R. (2003) The binding sites on human heme oxygenase-1 for cytochrome P450 reductase and biliverdin reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20069–20076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]