Abstract

Purpose

The treatment of choice for a displaced femoral neck fracture in the most elderly patients is a cemented hemiarthroplasty (HA). The optimal design, unipolar or bipolar head, remains unclear. The possible advantages of a bipolar HA are a better range of motion and less acetabular wear. The aim of this study was to evaluate hip function, health related quality of life (HRQoL), surgical outcome and acetabular erosion in a medium-term follow-up.

Methods

One hundred and twenty patients aged 80 or more with a displaced fracture of the femoral neck (Garden III and IV) were randomised to treatment with a cemented Exeter HA using a unipolar or a bipolar head. All patients were able to walk independently, with or without aids, before surgery. Follow-ups were performed at four, 12, 24 and 48 months postoperatively. Assessments included HRQoL (EQ-5D index score), hip function (Harris hip score [HHS]) and radiological acetabular erosion.

Results

The mean EQ-5D index score was generally higher among the patients with bipolar hemiarthroplasties at the follow-ups with a significant difference at 48 months: unipolar HAs 0.59 and bipolar HAs 0.70 (p = 0.04). There was an increased rate of acetabular erosion among the patients with unipolar hemiarthroplasties at the early follow-ups with a significant difference at 12 months (unipolar HAs 20 % and bipolar HAs 5 %, p = 0.03). At the later follow-ups the incidence of acetabular erosion accelerated in the bipolar group, and there were no significant differences between the groups at the 24- and 48-month follow-ups. There was no difference in HHS or reoperation rate between the groups at any of the follow-ups.

Conclusion

The bipolar HAs seem to result in better HRQoL beyond the first two years after surgery compared to unipolar HAs. Bipolar HAs displayed a later onset of acetabular erosion compared to unipolar HAs.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Hemiarthroplasty, Hip fracture, Elderly, Osteoporosis

Introduction

Contemporary evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) is now compelling that the treatment of choice for a displaced fracture of the femoral neck in an elderly patient is an arthroplasty [1–3]. In the majority of elderly and frail patients a cemented hemiarthroplasty (HA) is the treatment of choice for most surgeons [4]. When using an HA there are two types of articulations of the prosthesis and the patient’s acetabulum—unipolar or bipolar. Where the unipolar head has a single articulation between the prosthesis and the acetabulum, the bipolar head offers a second articulation between an inner smaller head and the polyethylene liner of the larger outer head. In theory this reduces stress on the acetabular surface and thereby acetabular erosion. Acetabular erosion is believed to cause pain and impaired hip function. Other proposed benefits are less risk for dislocation and better range of motion. Up to year 2008 bipolar HAs were more commonly used, compared to unipolar HAs in Sweden [5]. Since the 2008 annual report from the Swedish hip arthroplasty register, which reported an increased risk for reoperations for bipolar HAs, the trend has been that less bipolar and more unipolar HAs are used [5]. In contrast, data from our own institution on 830 Exeter HAs displayed no difference in reoperation rate between unipolar or bipolar HAs [6]. In a previous one-year follow-up of an RCT from our department including 120 patients randomised to uni- or bipolar HA, the bipolar group had superior results with less acetabular erosion compared to the unipolar group after 12 months [7]. This study is a four-year follow-up of these patients to evaluate the progress of acetabular erosion, health related quality of life (HRQoL) and hip function.

Patients and methods

This study was conducted at the Department of Orthopaedics, Stockholm South Hospital (Södersjukhuset) in Stockholm. From August 2005 to October 2008, 120 patients (91 females), mean age 86.1 years (range 79–100) with an acute displaced fracture of the femoral neck due to low-energy trauma were enrolled in the study. Fractures were classified as Garden III or IV [8]. Inclusion criteria were age 80 or older, independent living conditions, independent walking ability with or without walking aids and absence of severe cognitive dysfunction. Absence of severe cognitive dysfunction was defined as a score of 3 or more in the short portable mental status questionnaire (SPMSQ) [9]. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis in the same hip, history of mental illness, drug or alcohol abuse, pathological fractures and fractures older than 48 hours on admission were not included. After being cleared for surgery with an arthroplasty by the attending anaesthetist the patients were randomised (opaque sealed envelopes, independently prepared) to a hemiarthroplasty with either a unipolar or a bipolar head. Baseline data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline data for all patients included in the study (N = 120)

| Characteristic | Unipolar HA (n = 60) | Bipolar HA (n = 60) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (range) | 87.4 (80–100) | 85.5 (80–96) | |

| Mean cognitive function SPMSQ (range) | 8.5 (5–10) | 8.5 (5–10) | |

| Mean EQ-5D index score prefracture (range) | 0.80 (0.16–1.0) | 0.81 (0.16–1.0) | |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2)a | 22.8 (17 to 38) | 23.8 (17 to 33) | |

| Gender female (%) | 49 (82) | 42 (70) | |

| Walking aids (%) | None Stick or crutches Walking frame |

38 (63) 8 (13) 14 (23) |

46 (77) 7 (12) 7 (12) |

| ADL A or Bb | 58 (97) | 58 (97) | |

| ASA, classification (%) | 1 2 3 4 |

2 (3) 29 (48) 27 (45) 2 (3) |

0 (0) 30 (50) 29 (48) 1 (2) |

HA hemiarthroplasty, SPMSQ short portable mental status questionnaire, BMI body mass index, ADL activities of daily living, ASA American society of anaesthesiologists

aFive missing values in each group

b ADL Activities of daily living according to Katz. A indicates independence in all six functions, B indicates independence in all but one and C to G indicate dependence in bathing and at least one more function

Surgical procedures

All operations were performed by experienced orthopaedic surgeons (n = 16) and spinal anaesthesia was the standard procedure. A modified Hardinge approach [10] with the patient in the lateral decubitus position was used in all cases. The implant used was a cemented Exeter stem (Stryker Howmedica, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) with either a unipolar head (Unipolar head, Stryker Howmedica, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) or a bipolar head (UHR, Stryker Howmedica, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). The same cement (Refobacin G, Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA) and standard cementing technique was used for both procedures. The diameter of the inner head of the bipolar head was 28 mm in all cases. All patients were given three doses of intravenous Cloxacillin 2 g as antibiotic prophylactics and low molecular-weight heparin was given as thromboembolic prophylactics for ten–14 days. Postoperatively patients were mobilised the day after surgery and allowed weight bearing as tolerated.

Follow–up and assessments

After informed consent to participate in the study the primary assessment was made by a research nurse according to the recall principle: estimation of living conditions, walking ability, activity of daily living (ADL) according to Katz [11] and HRQoL during the last week prior to the trauma.

The postoperative follow-ups were performed at four, 12, 24 and 48 months after surgery and included both clinical and radiological assessments. The clinical evaluation included history of any adverse events or hip complications, hip function and HRQoL. Hip function was reported using the Harris hip score (HHS) [12]. The HHS contains four parameters: pain, function, absence of deformity and range of motion. Higher score means better hip function and the maximum score is 100. The HRQoL was assessed prior to fracture and at follow-ups with a generic instrument, the health part of EuroQol (EQ-5D index score) [13]. The score is self-reported and goes from 0, which indicates the worst possible health state, to 1 which indicates the best possible health state. If the patient was unable to attend the follow-up, a home visit was offered and carried out.

Acetabular erosion was evaluated by a radiologist (GL) and graded according to the method described by Baker [14]. The system is a four-step grading system: grade 0 (no erosion), grade 1 (narrowing of the joint space), grade 2 (acetabular bone erosion) and grade 3 (protrusio acetabuli).

Statistical analysis

A power analysis was used to determine sample size. To detect a five-point difference at the 12 month follow-up in the HHS we estimated a sample size of 120 patients. The estimation was made with 90 % power at a 95 % significance level. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for scale variables and ordinal variables in independent groups. Nominal variables were tested by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. All tests were two-sided. The results were considered significant at a p-value of <0.05. The statistical software used was IBM SPSS 20 for Windows and Sample Power 2.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, Il, USA).

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the Helsinki declaration and approved by the local ethics committee.

Results

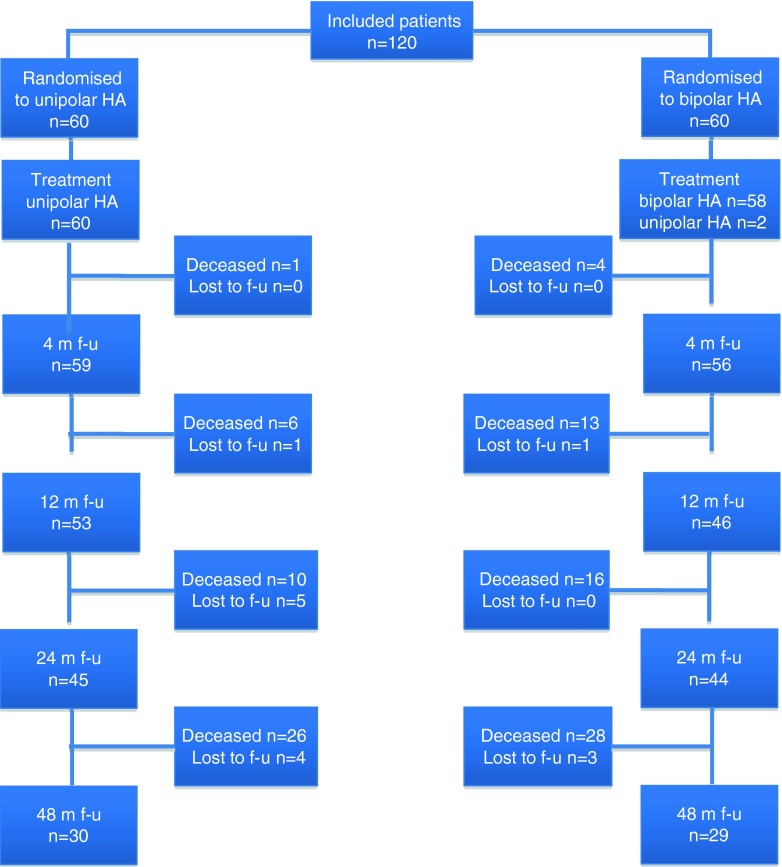

A flow chart for all patients included is displayed in Fig. 1. The bipolar heads were only available in dimensions from 44 mm to 72 mm and the unipolar heads in dimensions of 41 mm to 56 mm. Two patients randomised to bipolar HA had an acetabulum smaller than 44 mm and were therefore given a unipolar HA but analysed in the bipolar group according to the intention to treat principle.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for all patients included. HA hemiarthroplasty, f-u follow-up, m month

Surgical outcome

A total of 11 patients were revised due to fracture-related complications giving a total reoperation rate of 9.2 %. There was no significant difference in the reoperation rate between the unipolar (5 %, 3/60) and the bipolar (13 %, 8/60) groups (p = 0.2). The most common reason for a reoperation was a suspected deep infection (n = 4), a periprosthetic fracture (n = 4) followed by a prosthetic dislocation (n = 3). The complications resulting in a reoperation occurred within the first two months after surgery in ten of the patients, and after 15 months in one patient (a periprosthetic fracture). All four patients reoperated due to a suspected deep infection were treated with antibiotics plus open debridements (one to seven times), and tissues were collected for bacterial cultures, from which bacterial growth could be verified in three patients. Of the patients with a suspected deep infection three patients healed uneventfully, but in one patient the infection was persistent and the prosthesis was therefore removed before healing could be obtained. Out of the four patients sustaining a periprosthetic fracture, three patients were revised with revision of the stem to a long cemented Exeter stem and one patient was reoperated with revision of the stem to an uncemented LINK MP stem. All three patients who sustained a prosthetic dislocation were treated by closed reductions (one to three times) and have been stable afterwards (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data on the 11 patients undergoing reoperations

| Patient number | Gender | Group | Indication for reoperation | Reoperation | Time to reoperation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Male | Bipolar | Periprosthetic fracture | Stem revision to cemented long Exeter stem | 15 months |

| 18 | Female | Unipolar | Prosthetic dislocation | Closed reduction x 3 | 19 days |

| 20 | Female | Bipolar | Deep infection | Wound revision x 3 | 25 days |

| 34 | Female | Unipolar | Prosthetic dislocation | Closed reduction x 2 | 13 days |

| 40 | Male | Bipolar | Deep infection | Wound revision x 7 | 2 months |

| 41 | Male | Bipolar | Periprosthetic fracture | Stem revision to cemented long Exeter stem | 1 month |

| 68 | Male | Bipolar | Periprosthetic fracture | Stem revision to uncemented LINK MP stem | 1.5 months |

| 69 | Male | Bipolar | Periprosthetic fracture | Stem revision to cemented long Exeter stem | 2 months |

| 82 | Female | Unipolar | Deep infection | Wound revision x 5, finally extraction of prosthesis | 24 days |

| 86 | Female | Bipolar | Deep infection | Wound revision x1, negative culture | 18 days |

| 106 | Female | Bipolar | Prosthetic dislocation | Closed reduction x 1 | 15 days |

There was no difference in the mean duration of the surgery; 72 minutes (range 37–109) for the unipolar group and 69 minutes (range 39–126) for the bipolar group (p = 0.1). Nor were there any differences in the mean intraoperative blood loss between the unipolar patients, e.g. 290 ml (range 50–1,200) and the bipolar patients, e.g. 240 ml (range 50–600) (p = 0.3).

Health-related quality of life and functional outcome

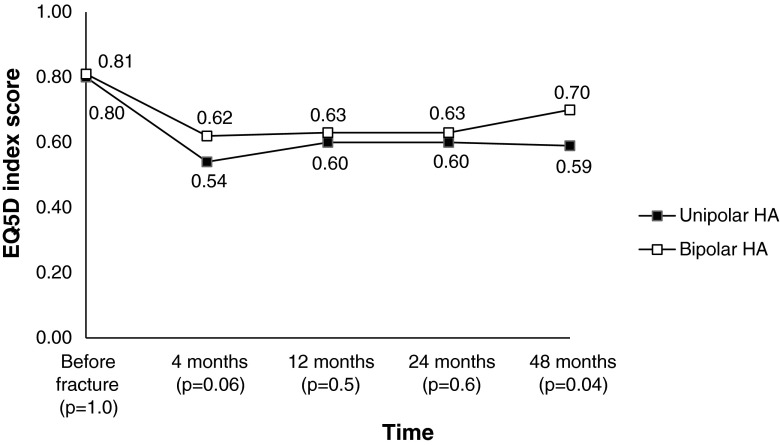

The EQ-5D index score was generally higher among the patients with bipolar hemiarthroplasties at the follow-ups with a significant difference at 48 months (p = 0.04) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Health related quality of life (mean EQ-5D index score) before fracture and at follow-ups. Missing values due to patients who declined; 4 months, n = 3; 12 months, n = 2; 24 months, n = 5; 48 months, n = 9. P-values are given for differences between groups

In the unipolar group the mean (± SD) EQ-5D index score decreased from 0.80 (0.21) (preinjury) to 0.54 (0.29) at four months. After a minor increase to 0.60 (0.30) at 12 months and 0.60 (0.34) at 24 months it was finally 0.59 (0.27) at 48 months.

In the bipolar group the mean (±SD) EQ-5D index score was similar as the unipolar group before the injury 0.81 (0.21). It decreased to 0.62 (0.30) at four months, 0.62 (0.30) at 12 months, 0.63 (0.31) at 24 months and at the final 48 months follow-up the score was 0.70 (0.26).

There was no difference in the total Harris hip score, or in the sub scores for pain, function, absence of deformity or range of motion between the groups at any of the follow-ups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean (range) Harris hip score for patients available at follow-ups

| Measure | Unipolar HA (n = 60) | Bipolar HA (n = 60) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 months, n = 114a | |||

| Total score | 73.8 (44–98) | 75.5 (24–95) | 0.2 |

| Pain | 39.5 (20–44) | 40.3 (10–44) | 0.2 |

| Function | 25.6 (5–45) | 26.6 (5–42) | 0.4 |

| Absence of deformity | 4.0 (4) | 4.0 (4) | 1.0 |

| Range of motion | 4.7 (3–5) | 4.6 (1–5) | 0.5 |

| 12 months, n = 99a | |||

| Total score | 78.2 (34–100) | 77.7 (33–100) | 1.0 |

| Pain | 41.3 (20–44) | 40.5 (20–44) | 0.9 |

| Function | 28.3 (5–47) | 28.6 (5–47) | 0.9 |

| Absence of deformity | 4.0 (4) | 4.0 (4) | 1.0 |

| Range of motion | 4.7 (3–5) | 4.6 (2–5) | 0.3 |

| 24 months, n = 89a | |||

| Total score | 76.6 (28–98) | 77.8 (50–100) | 1.0 |

| Pain | 40.9 (20–44) | 42.0 (30–44) | 0.6 |

| Function | 27.5 (0–45) | 27.6 (0–47) | 1.0 |

| Absence of deformity | 4.0 (4) | 4.0 (4) | 1.0 |

| Range of motion | 4.7 (4–5) | 4.6 (2–5) | 0.5 |

| 48 months, n = 59a | |||

| Total score | 75.8 (38–100) | 77.6 (46–100) | 0.9 |

| Pain | 41.5 (20–44) | 41.9 (20–44) | 0.5 |

| Function | 25.0 (5–47) | 27.9 (0–47) | 0.3 |

| Absence of deformity | 4.0 (4) | 4.0 (4) | 1.0 |

| Range of motion | 4.8 (4–5) | 4.7 (2–5) | 0.2 |

HA hemiarthroplasty

p-values are given for differences between groups

aMissing values due to patients declined; 4 months, n = 1; 12 months, n = 2; 24 months, n = 5; 48 months, n = 7

General complications and mortality

There was no statistical difference in the number of general complications between uni- and bipolar patients. In the unipolar group the general complications included pneumonia (n = 2), pressure ulcer (n = 2), myocardial infarction (n = 1) and pulmonary embolism (n = 1). In the bipolar group the general complications included pneumonia (n = 1), pulmonary embolism (n = 1) and deep venous thrombosis (n = 1).

The overall mortality at four months was 4.2 % (5/120), at 12 months 16 % (19/120), at 24 months 22 % (26/120) and at 48 months 45 % (54/120). There were no differences in mortality between unipolar and bipolar patients at any time. At 12 months the mortality was higher for males at 35 % (10/29) compared to females at 10 % (9/91) (p = 0.003). This was persistent at 24 months when the mortality was 38 % (11/29) for males and 17 % (15/91) for females (p = 0.02). At four and 48 months there were no differences in mortality between males and females.

Radiological outcome

There was an increased number of patients in the unipolar group, compared to the bipolar group, with an acetabular erosion at the early follow-ups with a significant difference at 12 months (p = 0.03). At the later follow-ups the incidence accelerated in the bipolar group, and there was no significant difference between the groups at the 24- and 48-month follow-ups. The acetabular erosion was grade 1 or grade 2 in all patients except in one patient in the unipolar group who displayed grade 3 erosion at the 24-month follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4.

The number of patients with available radiographs and acetabular erosion at the follow-ups

| Follow-up | Unipolar HA | Bipolar HA | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 months | 9/57 (16 %) | 3/55 (5.5 %) | 0.1 |

| 12 months | 10/49 (20 %) | 2/44 (4.5 %) | 0.03 |

| 24 months | 10/41 (24 %) | 5/37 (14 %) | 0.3 |

| 48 months | 5/26 (19 %) | 3/21 (14 %) | 0.7 |

HA hemiarthroplasty

a p-values are given for differences between groups

Discussion

This randomised controlled trial aimed to compare the HRQoL, functional and radiological outcomes after displaced femoral neck fractures in patients treated with a unipolar or a bipolar hemiarthroplasty. The main finding of the study was the difference in HRQoL in favour of the bipolar patients at 48 months.

To our knowledge, to date there are only six previous RCTs comparing unipolar and bipolar HAs [15–20]. All studies have their limitations which makes the results difficult to compare.

Health-related quality of life and hip function

In the previously published one-year follow-up of the same cohort of patients there was a tendency for lower EQ-5D index score in the unipolar group [7], but it was not until the 48-month follow-up when there was a significant difference with better EQ-5D index score among the bipolar patients. The study by Raia et al. is the only previous RCT using a validated HRQoL instrument (SF-36) [20]. They included 115 patients aged 65 years or older with an acute, displaced fracture of the femoral neck. Patients were operated upon with a cemented modular stem with either a bipolar (55 patients) or a unipolar (60 patients) head. Exclusion criteria were similar to our study. Only 78 (68 %) patients completed the one-year follow-up. They reported no difference in HRQoL, which accords with our study. Further comparisons of the results are not possible due to their short follow-up time (12 months).

In theory the bipolar prosthesis design with an additional inner articulation can entail a better range of motion and better functional outcome. However, we did not find any significant differences in the HHS total score, or in the HHS sub scores for pain, function, absence of deformity or range of motion between the groups at any time. These HHS results are in line with Davison et al. who performed a three-armed RCT with 93 patients in the internal fixation group, 90 patients in the unipolar group and 97 patients in the bipolar group [17]. The implants used were the now outdated cemented monobloc Thompson and Monk prostheses. The patients were annually reviewed for five years and the total amount of patients lost to follow-up after five years was 58 %. They reported no difference in HHS between the groups, but unfortunately the article does not state how many patients in each group were actually reviewed. Their total HHS scores were generally lower at every follow-up compared to our patients, which might be explained by the use of a now outdated prosthetic design. Calder et al. followed 118 patients with Monk prosthesis and 132 patients with Thompson prosthesis for two years [15]. At the final follow-up 67 (57 %) patients who received Monk prosthesis and 74 (56 %) patients with Thompson prosthesis were available. They found no difference between the groups in HHS but the article states no actual score values for comparison. Furthermore, Raia et al. followed their 115 patients with a self-reported musculoskeletal functional assessment instrument (MFA) but could not identify any significant difference at the one-year follow-up [20]. In contrast, Jeffcote et al. reported a significant difference in functional outcome in favour of the bipolar group at three months when comparing Exeter unipolar and bipolar HAs [18]. Of the original 51 patients only 37 (73 %) were available at three-month follow-up. There are no actual score values or p-values available in this article but at one point the authors state the WOMAC score to differ significantly in favour of the bipolar group at the three-month follow-up, and at another point the article states the HHS to differ significantly in favour of the bipolar group at the three-month follow-up. After three months there was no further significant differences in functional outcomes. Finally, Cornell et al. reported no difference in functional outcome (Johansen hip score) for their 48 patients after six-months follow-up [16].

Acetabular erosion

Recent data from the Swedish hip arthroplasty register published by Leonardsson et al. including 23,509 HAs operated between 2005 and 2010 displayed a substantially lower risk for revision due to acetabular erosion (HR = 0.3, CI 0.15–0.61) in favour of bipolar HAs when compared to unipolar HAs [21]. Comparisons in the 2010 Cochrane report on arthroplasties for the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures shows a decreased risk ratio for acetabular erosion in favour of bipolar HAs when compared to unipolar HAs [22]. Recently published RSA data on 18 patients from Australia displayed a significant reduction of acetabular erosion in the bipolar group compared to the unipolar group at 24-months follow-up [18]. Furthermore, after a mean follow-up of nine years, Avery et al. reported a rate of acetabular erosion of 100 % in the unipolar HA group, though only 13 of the original 41 patients were available for follow-up [23]. Of their 13 patients three (23 %) had enough symptoms due to acetabular erosion to justify revision surgery. In our study the unipolar HA group displayed an initial high rate of acetabular erosion (16 % after four months) but there was no further deterioration over time. In the bipolar group the acetabular erosion was significantly less at 12 months, but the rate of acetabular erosion then increased and at the later follow-ups there were no differences between the groups. This supports the previously reported finding that the bipolar articulation ceases to work after some time and thereby turns the bipolar prosthesis into a unipolar system [24–27]. Even if the HRQoL was better in the bipolar group at the last follow-up we found no correlation between presence of acetabular erosion and impairment in EQ-5D index score or HHS pain score at any of the follow-ups. None of our patients with acetabular erosion had enough symptoms to justify a reoperation, and in accordance with other authors [28] as well as data from the Swedish hip arthroplasty register [5] we believe acetabular erosion to play a minor role in the outcome after HA due to the low functional demands in this patient population.

Surgical outcome

We found no difference in reoperation rates between uni- and bipolar patients. This is in line with a previous study from our institution on 830 Exeter HA patients with a median follow-up time of three years, where no difference in reoperation rate between unipolar and bipolar HAs could be found [6]. In contrast Leonardsson et al. reported significantly higher risk for reoperation in bipolar HAs compared to unipolar ones in patients from the Swedish hip arthroplasty register including all HAs performed in Sweden between 2005 and 2010 [21]. However, there have been indications in earlier annual reports from the Swedish hip arthroplasty register that the risk for reoperation differs between different stem designs, and at first hand, other stems than the stem used in this study (the Exeter stem) might display a difference in reoperation rate between uni- and bipolar heads [5]. Leonardsson et al. like us, found that dislocations, periprosthetic fractures and infections were the most common reasons for reoperations [21].

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is that it is a long-term follow-up of a prospective randomised controlled trial. Furthermore, the use of a modern cemented and modular stem in both groups, the follow-up with a validated HRQoL instrument and the relatively long follow-up time of 48 months with both functional and radiological assessments are other strengths. A limitation is that we did not use a blinded observer for the functional follow-up. Although widely spread, the HHS might be debatable because of the suggested ceiling effect of this score [29].

Conclusions

The bipolar HAs seems to result in better health-related quality of life beyond the first two years after surgery compared to unipolar HAs. Bipolar HAs displays a later onset of acetabular erosion compared to unipolar HAs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Hans Törnqvist, Department of Orthopaedics, Stockholm South Hospital (Södersjukhuset) and Jan Tidermark, Department of Orthopaedics, Capio St. Görans Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden for their valuable contribution to the study.

This study was supported in part by grants from the Trygg-Hansa Insurance Company, through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet and the Swedish Research Council (VR).

References

- 1.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, Tornetta P, 3rd, Obremskey W, Koval KJ, et al. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck. a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(9):1673–1681. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frihagen F, Nordsletten L, Madsen JE. Hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation for intracapsular displaced femoral neck fractures: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335(7632):1251–1254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39399.456551.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogmark C, Johnell O. Primary arthroplasty is better than internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures: a meta-analysis of 14 randomized studies with 2,289 patients. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(3):359–367. doi: 10.1080/17453670610046262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Tornetta P, 3rd, Swiontkowski MF, Berry DJ, Haidukewych G, et al. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. An international survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):2122–2130. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Register SHA. Annual reports, http://www.jru.orthop.gu.se

- 6.Enocson A, Hedbeck CJ, Törnkvist H, Tidermark J, Lapidus LJ. Unipolar versus bipolar Exeter hip hemiarthroplasty: a prospective cohort study on 830 consecutive hips in patients with femoral neck fractures. Int Orthop. 2012;36(4):711–717. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedbeck CJ, Blomfeldt R, Lapidus G, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S, Tidermark J. Unipolar hemiarthroplasty versus bipolar hemiarthroplasty in the most elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures: a randomised, controlled trial. Int Orthop. 2011;35(11):1703–1711. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1213-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garden RS. Low-angle fixation in fractures of the femoral neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43-B(4):647–663. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatri Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64(1):17–19. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.64B1.7068713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. the index of adl: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51(4):737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker RP, Squires B, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in mobile, independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck. A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(12):2583–2589. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calder SJ, Anderson GH, Jagger C, Harper WM, Gregg PJ. Unipolar or bipolar prosthesis for displaced intracapsular hip fracture in octogenarians: a randomised prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(3):391–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornell CN, Levine D, O’Doherty J, Lyden J. Unipolar versus bipolar hemiarthroplasty for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in the elderly. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;348:67–71. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199803000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davison JN, Calder SJ, Anderson GH, Ward G, Jagger C, Harper WM, et al. Treatment for displaced intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur. A prospective, randomised trial in patients aged 65 to 79 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(2):206–212. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.11128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffcote B, Li MG, Barnet-Moorcroft A, Wood D, Nivbrant B. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis and clinical assessment of unipolar versus bipolar hemiarthroplasty for subcapital femur fracture: a randomized prospective study. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80(4):242–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2009.05040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malhotra R, Arya R, Bhan S. Bipolar hemiarthroplasty in femoral neck fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1995;114(2):79–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00422830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raia FJ, Chapman CB, Herrera MF, Schweppe MW, Michelsen CB, Rosenwasser MP. Unipolar or bipolar hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures in the elderly. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;414:259–265. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000081938.75404.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonardsson O, Kärrholm J, Akesson K, Garellick G, Rogmark C. Higher risk of reoperation for bipolar and uncemented hemiarthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):459–466. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.727076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker MJ, Gurusamy KS, Azegami S. Arthroplasties (with and without bone cement) for proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001706.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avery PP, Baker RP, Walton MJ, Rooker JC, Squires B, Gargan MF, et al. Total hip replacement and hemiarthroplasty in mobile, independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: a seven- to ten-year follow-up report of a prospective randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(8):1045–1048. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.27132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen SC, Badrinath K, Pell LH, Mitchell K. The movements of the components of the Hastings bipolar prosthesis. A radiographic study in 65 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(2):186–188. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B2.2925732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eiskjaer S, Boll K, Gelineck J. Component motion in bipolar cemented hemiarthroplasty. J Orthop Trauma. 1989;3(4):313–316. doi: 10.1097/00005131-198912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips TW. The Bateman bipolar femoral head replacement. A fluoroscopic study of movement over a four-year period. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(5):761–764. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B5.3680337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verberne GH. A femoral head prosthesis with a built-in joint. A radiological study of the movements of the two components. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1983;65(5):544–547. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B5.6643555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wachtl SW, Jakob RP, Gautier E. Ten-year patient and prosthesis survival after unipolar hip hemiarthroplasty in female patients over 70 years old. J Arthroplast. 2003;18(5):587–591. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsdotter A, Bremander A. Measures of hip function and symptoms: Harris Hip Score (HHS), Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS), Oxford Hip Score (OHS), Lequesne Index of Severity for Osteoarthritis of the Hip (LISOH), and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) Hip and Knee Questionnaire. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(Suppl 11):S200–S207. doi: 10.1002/acr.20549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]