Abstract

All the medical knowledge of all time in one book, the universal and perfect manual for the Renaissance surgeon, and the man who wrote it. This paper depicts the life and works of Giovanni Andrea della Croce, a 16th Century physician and surgeon, who, endowed with true spirit of Renaissance humanism, wanted to teach and share all his medical knowledge through his opus magnum, titled “Universal Surgery Complete with All the Relevant Parts for the Optimum Surgeon”. An extraordinary book which truly represents a defining moment and a founding stone for traumatology, written by a lesser known historical personality, but nonetheless the Renaissance Master of Traumatology.

Keywords: History of surgery, Ancient traumatology, Giovanni Andrea Della Croce, Renaissance

Introduction

The beginning of surgical practice started with the very first years of human civilisation. Probably the origin of surgery has more to do with archaeology than history, since human remnants have been discovered, dating back to Neolithic times, revealing evidence of surgical treatment. In particular, skull trephination [1] was a common procedure among different cultures and this accounts for the primordial origins of surgery. Before the advent of drawings, sculptures, and written sources, ancient men were likely to perform surgical procedures to treat disparate conditions. Over the past centuries, several records have been produced on the current status of medical and surgical knowledge: we may remember some Egyptian papyri or even the Hammurabi Codex, and also the flourishing medical literature of the Greek and Roman times [2, 3]. In this fascinating scenario, the role played by orthopaedics, and in particular by traumatology, is pre-eminent since traumatic injuries were one of the main causes of disability and death in times when unsafe working conditions were quite common and also wars were part of the everyday life of several populations. Thus, the great interest in the treatment of traumatic conditions and their sequelae by old physicians can be easily explained. But to ask a question that might sound banal, who had to take care of these diseases? The answer seems tremendously easy: the surgeon. What is not banal is the fact that “the surgeon” and “the physician” have been distinct figures for a long time, with the latter receiving much more social and cultural consideration than the former. During the Middle Ages there was the figure of the barber-surgeon, who was a little bit more than a craftsman and a lot less than a physician. Compared to the “doctor humanae medicinae” he lacked any academic training and his profession was just the result of an “on the field” apprenticeship.

The very first academic textbook on surgery, the “Practica Chirurgiae” by Rogerius Salernitanus [4], dates back to the last years of the 12th century and represented the foundation of Surgery as a branch of medicine worthy of recognition in the newly born Universities. From that date, however, it was still necessary to wait more than three centuries to have any considerable advancement in the perception of surgical practice and the figure of surgeon. It is not by chance that the advent of the Renaissance also shone a bright light onto the role of surgery and surgeons. In that revolutionary period so many geniuses contributed to shaping a new conception of humans and their potential. The establishment of the scientific method by Galileo Galilei [5] and the fundamental works in the field of anatomy and pathology by people such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Andreas Vesalius [6, 7] and Antonio Benivieni [8] set the stage for the development of a new surgical practice. Beyond the eminent figures mentioned, who are well known to every reader, it is equally important to remember some less celebrated personalities who, endowed with the same Renaissance spirit, helped to define new standards in their particular discipline. In the case of traumatology, Giovanni Andrea della Croce is truly a remarkable figure. His fundamental book “Chirurgiae Universalis Opus Absolutum” clearly reflects the Renaissance concept that knowledge should be universal and Man is, at the same time, the custodian and the addressee of this effort. As we will see, in his book about “Universal Surgery” the role played by the principles of Traumatology is so important that Giovanni Andrea della Croce could be regarded as the Renaissance Master of Traumatology.

Giovanni Andrea Della Croce: biographical note

Giovanni Andrea Della Croce (sometimes known as Dalla Croce, De Cruce or Crucejus) was born in Venice in 1515, according to some in 1514 and to others in 1509 [9]. His father was a barber-surgeon native to Parma, himself son of a renowned surgeon in the service of the Duke of Milan.

As a young man in Renaissance Italy, he developed a passion for studying the classics of medical literature written by Greek and Arab physicians, and soon entered medical practice with his father; in 1532 he became member of the Surgical Board of Venice, one of the most respected medical corporations of the time.

Ten years later he was promoted for the first time to the position of Prior inside the Board [10] and he held this office again in 1548, 1550, and 1558.

In 1537 he moved to the flourishing Dukedom of Feltre to serve as an “expert in surgery and physics”. He left the city in 1546 after one of his sisters was raped by a local noble man, who got away unpunished.

After returning to Venice, Della Croce was appointed physician of the Venetian fleet and later, because of his expertise in many medical fields, he received the assignment to develop the city’s defenses against the plague.

Giovanni Andrea Della Croce died in 1575 in Venice with all his family during the following epidemic of plague; they refused to abandon the city [11] and for his great contributions and dedication to the welfare of Venice, a bridge was dedicated to his memory that we can still find today on the island of Giudecca.

Chirurgiae Universalis Opus Absolutum [12]

This book was first published in Latin in 1573 in Venice; at that time, Giovanni Andrea Della Croce was already of advanced age, no longer active in the medical practice but still eager to promote and improve knowledge in the art of surgery. Released, for health reasons, of his commitments with the Surgical Board of Venice, he could devote himself to writing [11].

The production of this book took years, as one of his volumes, the one about bullet wounds, was previously published in 1560, also in Venice, with the title of ‘Two New Essays’. The success of this work was immediate and long-lasting throughout the following century: an Italian translation was published in 1574, with reprints in 1583, 1605, and 1661 (an English translation of the title might be: “Universal Surgery Complete with All the Relevant Parts for the Optimum Surgeon. Containing all the Theories and all the Practices needed in Surgery”); the Latin version was reprinted in 1596 and a first German translation is dated 1606 in Frankfurt (“Officina Aurea, das ist guldene Werkstatt der Chirurgy oder Wundt Artzney”) [13].

The reason for its success and longevity is to be found in the nature of the project: Della Croce was truly a man of the Renaissance, a humanist (at the time, surgery was still considered an art and not yet a science) religiously involved in becoming the archetype of the polymath, a man with expertise in different subjects, a researcher of the universal knowledge.

Chirugiae Universalis, as the title states, is a book containing all the medical knowledge of the time in the field of surgery: traditional knowledge, new discoveries, experience from all around Europe and Asia, and inventions from the Author’s own ingenuity too. Every sliver of knowledge is dealt with the same amount of respect, whether it is from Hippocrates or from Della Croce’s contemporaries.

Della Croce’s book was the first in medical history to show a collection of all the known surgical instruments, with drawings and a guide on how to use them: for example, the ‘Vertibulo Comune’ or ‘Common Drill’ (Fig. 1) is described in minute detail as ‘an instrument made of iron, square and hollow at the bottom to allow the insertion of the drill bits; bent in the middle and with a rotating ball on top. Place the bits on the head, and with one hand holding the ball, with the other you turn the middle section.’ In many cases, these devices were thought up by Della Croce himself, designed to respond to needs that current medical technology did not know how to fulfill, or to improve a basic instrument with more sophisticated and efficient solutions.

Fig. 1.

Common drill: side by side of the original instrument (part of the collection belonging to the Donazione Putti Museum, Bologna, Italy) and its design as depicted inside Chirurgiae Universalis

It was also the first book to introduce and present synonyms for the Greek, Latin and Arabic names of pathologies [14].

In centuries without a real school or teaching system to instruct surgeons, it soon became indispensable for anyone with interest in surgery, a master key to access the whole spectrum of medical practice.

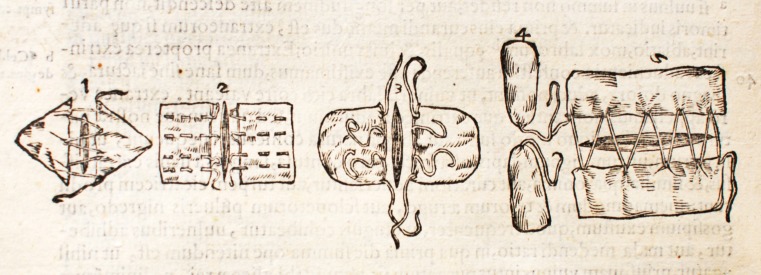

Fifty more years after the experience of Hans von Gersdorff and his “Field Book of Surgery” [15], Della Croce expanded the growing concept of a handbook to incorporate every aspect of a still unacknowledged profession; to a surgeon in the 16th and 17th Century, the Chirurgiae Universalis was a fundamental guidebook to understand and train in the treatments of little ailments, serious diseases, and especially how to act in case of war wounds, during and after a battle. It is no accident that the first written part of this book was about ‘traumatology’ because the understanding and prominence of how to deal with combat-related injuries could make the career fortune of a surgeon (besides saving the lives of men), and it was the most sought-after skill for an operator in this field. It must not be forgotten that Della Croce himself owed his personal success to his proficiency with these kinds of wounds, which earned him the position of surgeon in chief for the Venetian fleet. His deep experience was also revealed by the obsessive care of every detail, whereby he was meticulous and precise in representing every possible variation of every procedure considered, from suturing a wound (Fig. 2) to the many ways to operate around a head injury (Fig. 3). Notably, he also performed these procedures at his own home, as did many surgeons of that time (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Different suture techniques according to the wound type

Fig. 3.

Head wounds. These are only some of the many examples of treatments for head wounds depicted inside Chirugiae Universalis

Fig. 4.

Hospital at home. Often the surgeons had to operate inside their own home, among children, crying relatives and animals, unthinkable to us, but not so different from the situations found in poor countries or war zones around the world

It is impossible to analyse and describe all the sections of the book, but it is interesting and amazing at least to itemise the structure and the topics of this tremendous work.

It consists of seven books, each divided into a different number of thematically consistent essays.

Each part reflects a similar framework: a general introduction to the kind of pathology at hand followed by the listing of all the specific cases, grouped by closeness in nature, with the corresponding treatments (hereinafter all the italics are English translations made by the authors of the original Italian/Latin words and phrases).

The first book contains six essays about tumours or Apostemes: a general introduction, apostemes of the blood (i.e. pimples, abscesses, etc.) with a specific attention to avoid or contain their spreading, choleric apostemes (such as herpes and blisters), phlegmatic apostemes (i.e. oedema and nodules), melancholic apostemes (cancer, aneurysms, etc.), and ending with outgrowths like calluses or warts.

The second book is composed of seven essays about wounds: head wounds and their treatments, wounds to the face, wounds to nerves and tendons and ligaments, chest wounds, abdominal wounds, how to extract arrows from the chest or other body parts, and bullet wounds.

The third book contains five essays about ulcers: an introduction, simple and pure ulcers, particular ulcers, universal nature of fistulas, how many and what are the affections of the skin.

The fourth book is made up of two essays about bone fractures: bone fractures and bone dislocations.

The fifth book contains twelve essays about different medical procedures: how to cauterise and the use of veficatories (inflammatory medicines), phlebotomy, use of suction cups, use of leeches, how to extract a stillbirth child, rectal procidentia (prolapses) and other passions belonging to these places, cataracts, how to extract stones from the bladder, how to treat teeth affections, and a discussion on the French disease (Syphilis) with its universal treatment.

The sixth book consists of two essays about antidotes: a list of all the antidotes, simple and composite, proposed by contemporary scholars of this art, and a list of all the antidotes proposed by different Auctoritates of the past.

The seventh and last book contains a list, drawings and guides of all the instruments, ancient or modern, that might be necessary in the art of surgery and teach all inquisitive people the universal practice of the admirable art of medical care.

The most recognised biographer of Della Croce, Prof. Davide Giordano, did not hesitate to call him an ‘Ambrose Paré of the Lagoons’ [9], a father of surgery and a master in battlefield medicine. Giordano was sure that Paré himself was aware of Della Croce’s works on the treatment of war wounds (‘Two New Essays’ is dated 1560), and these papers might have been a source for Paré’s later writings.

Here follows an abridged translation of the introduction to the second book:

Doctors describe three types of weapons (Fig.5), which thrust with violence can easily enter the flesh.

The first is acute and short like an arrow, which it hides itself in the body and easily penetrates into it, and often it must be pulled out from the side opposite to that from which it entered, because very often it has edges that will tear the flesh much more if pulled from where it entered than if pushed in the opposite direction.

The second is wide and long like a spear, which, when stuck in the body, it is not convenient to take it out from the other side so as not to cause more damage than the spear itself did when entering.

The third is spherical, that is round, or angular like a ball of lead, or iron, or stone, or any other metal or hard substance, which, as it penetrates the skin and into the flesh, remains there as a whole and should be taken out from the side which it entered.

About these wounds caused by the third, round, type of weapon, the ancients did not mention them because they had no knowledge of them.

Therefore, about these wounds, we shall make a brief digression because often, being in battles and skirmishes, at sea as well as on land, diverse sorts of balls, chains, scales of marble and similar things are shot against men by those evil tools such as muskets, rifles, guns, mortars, falconets, cannons, etc. etc.

The following injury is combined together with its cause, which some call ‘joint cause’, which is a part of the wound and can be an aggravation in progress; these wounds are also often partnered by a friction, a laceration, a breaking of bones, a cruel pain, a general infection of the injured part, a swelling, often a burning and sometimes even a kind of poison, a corruption of the limb.

Necessarily so, these kinds of wounds are complicated by various symptoms and damage, but, although different ways could be chosen for treatment, we always start from the principle that the most immediate issue to be dealt with is not to leave anything unnatural in the wound. Hence this is where you have to start, as first treatment, because otherwise the wound cannot be healed.

The second step is to remove the pain; the pain cannot wait and hastens to the place that hurts as much material as possible in proportion to the bodily fluids that run through the wound, thus making it swell.

The third step is an appropriate preparation of the wound, or as they say, the digestion of the torn or damaged part of the wound (to avoid gangrene with medicine or any other actions); the fourth step is cleaning of the wound, according to need, and the application of medicine to make the flesh regrow, and finally to stitch the wound.

The fifth and final step is to deal with and correct any other damage that might occur during or resulting from this intervention (pain, inflammation, fever, etc. etc.).

Fig. 5.

Weapons & projectiles: a selection from the huge amount of arrows, spears and projectiles displayed inside Della Croce’s book

These are still basic principles of wound management. The fact that Della Croce assessed them almost 500 years ago clearly demonstrates his genius and distinguishes him as a Master of traumatology.

Conclusion

A talented mind and a skillful surgeon, Giovanni Andrea Della Croce deserves to be remembered for his exceptional contribution to laying down some fundamental principles of traumatology. However, besides his merits as a traumatologist, what is truly amazing is his attitude towards new discoveries and his constant will to perfect surgical techniques and share his knowledge to make it universal: in this sense a real Renaissance Man, and at the same time a figure we can look back upon as a precursor of our very own way to understand medicine. “Modern surgery” is thought to have started with the discovery of the antiseptic method and anaesthesia; it is certainly true that those achievements marked a revolution in surgical history but they were mainly technical aspects. Looking at eminent traumatologists such as Hans von Gersdorff [15], Giovanni Andrea della Croce, Ambroise Pare [16], it is impossible not to recognise their brilliance and the modernity of their thoughts. Perhaps, “modern surgeons” were born before the date we usually regard as the beginning of modern surgery.

In the introduction to his book, Della Croce explains the meaning and the subject of surgery, i.e. “the cure of all wounds”, looking at every wound as a solution of the continuity of something purposely joined. It is fascinating to think that this concept of surgery was a mirror of Della Croce’s understanding of knowledge: “[the subject of surgery is] the union of all the separated sections of every part of the living human body”; a united, healthy body and a united, universal knowledge.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Liliana Draghetti (Donazione Putti, Biblioteche Scientifiche, Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute) and Keith Smith (Task Force, Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute) for their help.

All the authors of this paper declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Agelarakis A. Artful surgery: Greek archaeologists discover evidence of a skilled surgeon who practiced centuries before Hippocrates. Archaeology. 2006;59:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longrigg J. Greek rational medicine: philosophy and medicine from Alcmæon to the Alexandrians. London & New York: Routledge; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson R. Doctors and diseases in the Roman Empire. London: British Museum Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keil G. Roger Frugardi and the tradition of Langobardic surgery. Sudhoffs Arch. 2002;86:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weidhorn M. The person of the millennium: the unique impact of Galileo on world history. Lincoln, NE: Iuniverse; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Malley CD. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514–1564. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vesalius A (1543) De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. Ex officina Joannis Oporini, Basel

- 8.Benivieni A. De abditis nonnullis ac mirandis morborum et sanationum causis. Florence: Impressum Florentiae; 1507. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giordano D. Giovanni Andrea della Croce. Rassegna Clinico Scientifica. 1939;2:73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giordano D. Nuovi Documenti Biografici su Giovanni Andrea Dalla Croce. Giornale Veneto di Scienze Mediche. 1934;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Ferrari A. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 36. Roma: Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana; 1988. pp. 796–798. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Della Croce G (1573) Chirugiae Universalis Opus Absolutum. Jordanus Zilettus, Venice

- 13.Pazzini A. Bio-Bibliografia della Chirurgia. Roma: Cosmopolita; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castiglioni A. Storia della Medicina. A. Milano: Mondadori; 1927. pp. 409–410. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Matteo B, Tarabella V, Filardo G, Viganò A, Tomba P, Marcacci M. The traumatologist and the battlefield: the book that changed the history of traumatology. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:339–343. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827d0c9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernigou P. Ambroise Paré III: Paré’s contributions to surgical instruments and surgical instruments at the time of Ambroise Paré. Int Orthop. 2013;37(5):975–980. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1872-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]