Abstract

The identification of biomarkers in colorectal cancer (CRC) diagnosis and therapy is important in achieving early cancer diagnosis and improving patient outcomes. The aim of this study was to examine clinical significance of miR-218 expression in sera and tissues from CRC patients. A total of 189 cases and 30 healthy subjects were included. The expression levels of miR-218, SLIT2 and SLIT3 were measured by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). The relationship between miR-218 expression and clinicopathological characteristics was investigated. The expression levels of miR-218, SLIT2 and SLIT3 in CRC tissues were decreased than those in adjacent normal tissues (all P < 0.05). miR-218 expression was significantly associated with TNM stage, lymph node metastasis (LNM) and differentiation (all P < 0.05). Patients with low miR-218 expression had shorter survival time than those with high miR-218 expression (P = 0.036). Furthermore, the expression levels of serum miR-218 in CRC patients were lower than those in controls (P = 0.005). An increased level of serum miR-218 was found 1 month after surgery (P = 0.026). In conclusion, the miR-218 may has important roles in the development and progression of CRC and be a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of CRC.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, miR-218, microRNA, survival, expression

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common gastrointestinal cancer, with over 1.2 million new cancer cases and 608,700 cancer deaths estimated to have occurred in 2008 [1]. In china, CRC is the third most common cancer by annual incidence and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death [2], with an upward trend in incidence rate in recent decades. Given that there are typically no specific symptoms in the early stage of CRC, most patients are diagnosed in an advanced stage. Current treatments for CRC include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and targeted therapy, but the five-year survival rate is still not high, especially in patients with advanced CRC [3]. Early diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of CRC are crucial for timely and appropriate treatment. Thus, an urgent need exists to develop new screening tools and identify biomarkers for CRC.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a large class of evolutionarily conserved endogenous noncoding RNAs of about 20 to 25 nucleotides with intrinsic regulatory functions. miRNAs negatively regulate expression of target genes at the post-transcriptional level through mRNA degradation, translational repression, or miRNA-mediated mRNA decay [4]. It is well known that miRNAs play crucial roles in diverse biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and tumorigenesis. miRNAs can function as oncogenes and/or tumor suppressors [5], depending on their specific gene targets. Different types of cancer show different and specific miRNA expression profiles [5,6]. miRNAs could be promising biomarkers for cancer diagnosis [7], prognosis [8-10] and prediction of treatment response [11-13].

Recent studies have demonstrated that miR-218 is downregulated in various types of cancer, including cervical, gastric, lung, colon, prostate and bladder cancer [14-22]. In colon cancer, miR-218 inhibits cancer cell proliferation, suppresses cycle progression, and promotes apoptosis by down-regulating BMI-1 expression [19]. In the present study, we investigated whether miR-218 expression was associated with outcome of CRC patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethical and Scientific Committees of Taizhou People’s Hospital. Primary tumor specimens were obtained from 189 patients (79 females and 110 males) diagnosed with CRC who underwent complete resection in Taizhou People’s Hospital between 2006 and 2008. Patient characteristics, including age, gender, TNM stage, lymph node status, tumor size and histological grade, were retrospectively collected (Table 1). Twenty-six fresh specimens including both CRC tissue and corresponding normal tissue were also collected and stored at -80 °C immediately after resection. A total of 60 sera were collected from 30 CRC patients. Serum samples were collected prior to the surgery and 1 month after surgery. No patient was treated with radiotherapy or chemotherapy prior to surgical resection. Furthermore, 30 age and gender matched healthy individuals were included in our study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to sample collection.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of CRC patients

| Characteristics | No. of Patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 65.3 | |

| range | 30-83 | |

| Gender | ||

| female | 79 | 41.8 |

| male | 110 | 58.2 |

| TNM stage | ||

| I | 24 | 12.7 |

| II | 73 | 38.6 |

| III | 81 | 42.9 |

| IV | 10 | 5.3 |

| unknown | 1 | 0.5 |

| lymph node metastasis | ||

| no | 104 | 55.0 |

| yes | 85 | 45.0 |

| Tumor size | ||

| > 4 | 129 | 68.3 |

| ≤ 4 | 58 | 30.7 |

| unknown | 2 | 1.1 |

| Differentiation | ||

| well | 36 | 19.0 |

| moderate | 102 | 54.0 |

| poor | 51 | 27.0 |

RNA isolation

RNA was extracted from fresh-frozen and formalin-fixed tissues, and serum samples using TRIzol reagent, PureLink™ FFPE RNA Isolation Kit and mirVana PARIS kit (Life Technology, California, USA), respectively, following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was recovered in 50 μl of RNase-free water and stored at -80 °C before use. The RNA concentration was measured by NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, DE, USA).

Protocol for the detection of miR-218

The reverse transcription reaction was carried out using a TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) in a total volume of 10 μL containing 3.33 μL RNA, 1 μl 10 × reverse transcription buffer, 0.67 μL Mutiscribe Reverse Transcriptase, 0.13 μL RNase Inhibitor. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 16 °C, 30 min at 42 °C, 5 min at 85 °C for 5 min, and then held at 4 °C. Next, quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was run on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). qRT-PCR was carried out in a total of 20 μl volume containing 1.33 μl cDNA, 1 × Universal PCR Master Mix and 1 μl gene-specific primers and probe. PCR parameters were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. All reactions were performed in triplicate. The expression of miR-218 from tissue sample was normalized to the endogenous reference gene RNU6, whereas the cel-miR-39 was used as the reference control for serum samples [23].

Protocol for the detection of SLIT2 and SLIT3

The reverse transcription reaction was performed using PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was carried out using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara, Dalian, China) in a total volume of 20 μl on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 3 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. The sequences of the primer pairs were as follows: SLIT2 forward (5’-AGCCGAGGTTCAAAAACGAGA-3’) and SLIT2 reverse (5’-GGCAGTGCAAAACACTACAAGA-3’); SLIT3 forward (5’-GAATATGTCACCGACCTGCGACT-3’) and SL-IT3 reverse (5’-GCAGGTTGGGCAACTTCTTGA-3’); RPL13A forward (5’-CCTGGAGGAGAAGAGGAAAGAGA-3’) and RPL13A reverse (5’-TTGAGGACCTCTGTGTATTTGTCAA-3’). RPL13A was used as the reference gene.

Statistical analysis

The relative changes in gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Cases were divided into 2 groups, high or low, using the median miR-218 expression as a cutoff. The chi square or Fisher’s exact probability test was used to examine possible correlations between miR-218 expression and clinicopathologic features. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the survival rate, and differences in survival of subgroups of the study were compared by log-rank test. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc, IL, USA). All analyses were performed in all cases by using Mann–Whitney U-test or Wilcoxon nonparametric test.

Results

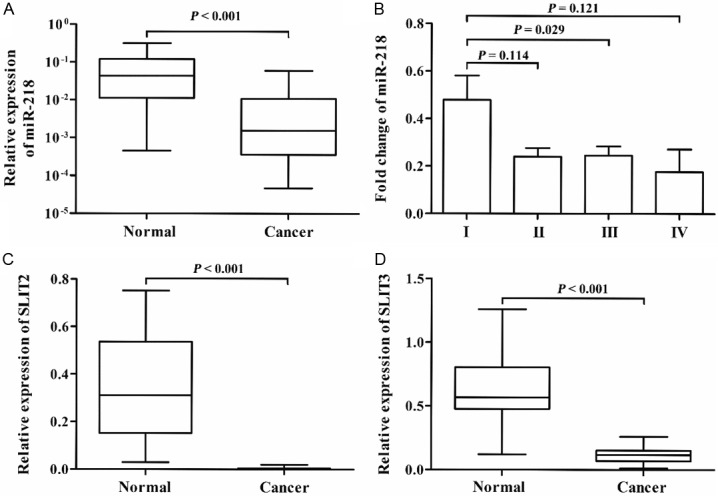

The expression levels of miR-218 and SLIT2 in CRC

We quantified miR-218 in 189 pairs of CRC and paracancerous tissues using qRT-PCR. The miR-218 was significantly downregulated in CRC tissue compared with the adjacent noncancerous tissues (fold-change = 0.27, P < 0.001, Figure 1A). The expression levels of miR-218 in patients with TNM stage I were higher than those in patients with TNM stage II~IV (P = 0.038). In addition, to confirm predicted host gene down-regulation, we also examine the expression levels of SLIT2 and SLIT3 in 26 pairs of CRC and adjacent normal tissues. As expected, the expression levels of SLT2 and SLT3 in CRC tissues were significantly lower than those in the corresponding noncancerous tissues (all P < 0.001). The expression of miR-218 was co-regulated with SLIT2 and SLIT3 expression (all P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

miR-218, SLIT2 and SLIT3 were downregulated in CRC. A: The expression level of miR-218 in CRC patients (n = 189). B: The expression level of miR-218 in CRC patients (n = 189) at different clinical status. C and D: The expression levels of SLIT2 and SLIT3 in CRC patients (n = 26), respectively.

Relationship between miR-218 expression and clinicopathological features in CRC patients

Patient characteristics with respect to miR-218 expression were shown in Table 2. The Chi-square test showed that miR-218 expression was associated with TNM stage, lymph node metastasis (LNM) and differentiation (P = 0.001, 0.004 and 0.025, respectively). No association was found between miR-218 expression and age, sex, as well as tumor size (all P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Association between miR-218 expression and the clinicopathological features

| Characteristics | miR-218 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Low | High | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.461 | ||

| > 60 | 64 (68.8) | 70 (73.7) | |

| ≤ 60 | 29 (31.2) | 25 (26.3) | |

| Sex | 0.932 | ||

| female | 39 (41.5) | 40 (42.1) | |

| male | 55 (58.5) | 55 (57.9) | |

| TNM stage | 0.001 | ||

| I | 5 (5.3) | 19 (20.2) | |

| II | 32 (34.0) | 41 (43.6) | |

| III | 49 (52.1) | 32 (34.0) | |

| IV | 8 (8.5) | 2 (2.1) | |

| LNM | 0.004 | ||

| no | 42 (44.7) | 62 (65.3) | |

| yes | 52 (55.3) | 33 (34.7) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.715 | ||

| > 4 | 63 (67.7) | 66 (70.2) | |

| ≤ 4 | 30 (32.3) | 28 (29.8) | |

| Histology grade | 0.025 | ||

| well | 12 (12.8) | 24 (25.3) | |

| moderate | 50 (53.2) | 52 (54.7) | |

| poor | 32 (34.0) | 19 (20.0) | |

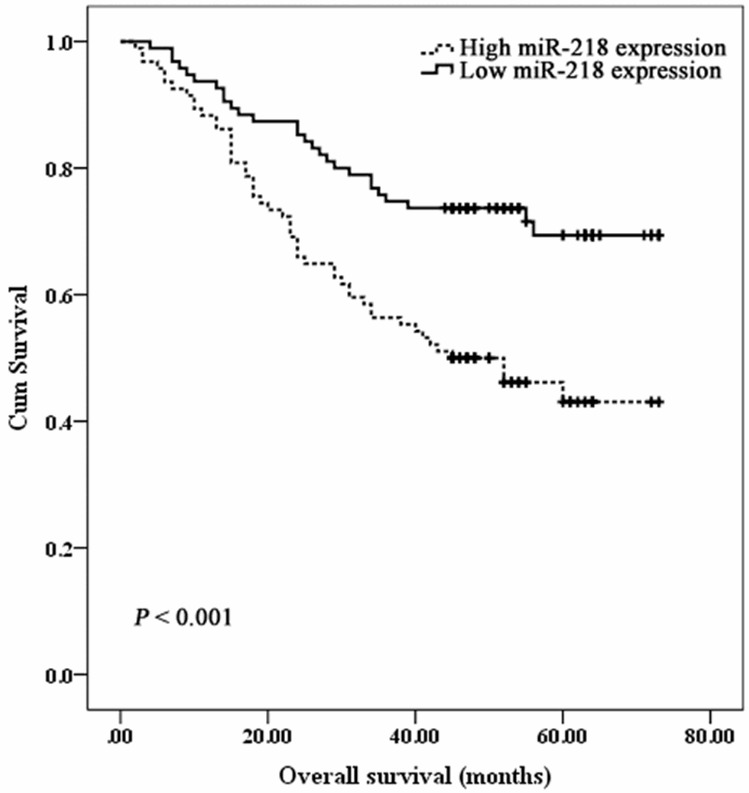

Association between miR-218 expression and survival in CRC patients

During the follow-up period of 73 months, 77 of 189 (40.7%) CRC patients died due to disease progression. Twenty seven of 95 (28.4%) patients with high miR-218 expression died from CRC. In the group of patients with low miR-218 expression, 50 of 94 (53.2%) died from CRC. Median survival time (MST) of patients with low miR-218 was 45.0 months (range 2 to 73 months), and MST of patients with high miR-218 expression was 58.6 months (range 4 to 73 months). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed a statistically significant association between low miR-218 expression and worse survival (P = 3.9 × 10-4, Figure 2). Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that overall survival was strongly influenced by TNM, differentiation, LNM and miR-218 (Table 3). Similar results were obtained in multivariate COX regression analysis.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival and miR-218 expression in group of 189 CRC patients.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of overall survival

| Features | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| age (years), > 60 v ≤ 60 | 0.814 (0.488-1.356) | 0.429 | ||

| sex, male v female | 0.994 (0.631-1.563) | 0.978 | ||

| tumor size (cm), > 4 v ≤ 4 | 0.743 (0.450-1.227) | 0.246 | ||

| tumor differentiation, moderate, poor v well | 2.684 (1.853-3.886) | 1.72 × 10-7 | 2.067 (1.412-3.026) | 1.90 × 10-4 |

| TNM stage, III+IV v I+II | 1.790 (1.131-2.832) | 0.013 | 1.662 (1.048-2.634) | 0.031 |

| LNM, yes v no | 3.323 (2.066-5.344) | 7.33 × 10-7 | 2.305 (1.403-3.788) | 0.001 |

| miR-218, low v high | 2.276 (1.423-3. 640) | 0.001 | 1.681 (1.034-2.731) | 0.036 |

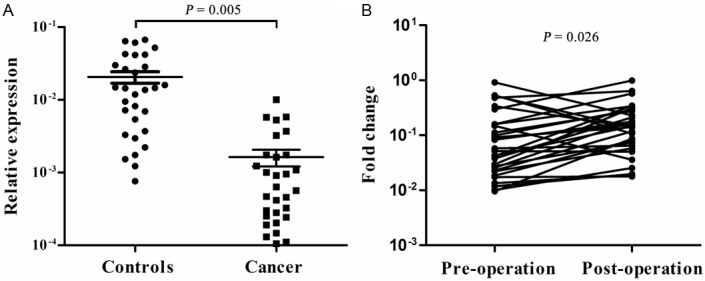

Evaluation of miR-218 expression in serum of CRC patients

Finally, we hypothesized that low miR-218 expression in CRC tissues might influence serum levels of miR-218 in CRC patients. To evaluate serum expression of miR-218 in cancer surveillance, we performed qRT-PCR on 30 sera from CRC patients and 30 sera from healthy controls. The expression levels of serum miR-218 in CRC patients were significantly lower than those in controls (P = 0.005, Figure 3A). Furthermore, the expression of serum miR-218 was increased after surgery (P = 0.026, Figure 3B). Twenty five of 30 patients showed increased levels of miR-218 after surgery, with a 135.5% mean increased, whereas 5 patients showed a decreased. All these 30 CRC patients showed no evidence of progression after initial surgery.

Figure 3.

Serum miR-218 levels. A: Serum miR-218 expression in CRC patients (n = 30) and controls (n = 30). B: Changes in serum miR-218 levels before (Pre-operation) and after surgery (Post-operation).

Discussion

A large number of genetic and epigenetic alterations are involved in carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Among these alterations, miRNA has been shown to regulate the expression of multiple target genes at the transcriptional level. Abnormal expression of miRNA is associated with cancer initiation, progression and metastasis [5,6]. Thus, miRNAs provide a useful starting point in understanding cancer etiology at the molecular level, specifically in looking for optimal biomarkers and exploring gene therapy. These may in turn improve cancer diagnosis and treatment.

miR-218 is dysregulated in different cancers [14-18]. miR-218 precursors, miR-218-1 and miR-218-2, are produced from two different genomic loci. Both miR-218-1 and miR-218-2 are located in the intronic regions of the SLIT2 gene on chromosome 4p15.2 and SLIT3 on chromosome 5q35–q34, respectively [24]. Allelic losses of chromosome 4p15.2 and 5q35–q34 are frequently found in a variety of cancers, including CRC [24,25]. In addition, SLIT2 and SLIT3 are also frequently hypermethylated in human cancer [21,24,26]. Therefore, SLIT2 and SLIT3 are commonly downregulated in human cancer due to allelic loss and promoter hypermethylation. In the present study, we also found that the expression levels of miR-218, SLIT2 and SLIT3 were lower in CRC tissues, and downregulation of SLIT2 and SLIT3 was concordant with decreased expression of miR-218. The expression levels of miR218, SLIT2 and SLIT3 were restored in cancer cells treated with 5-Aza-2’-deoxycytidine [24,27]. Underexpression of SLIT2 and SLIT3 is the main cause for reduced miR-218 expression [14,27]. Furthermore, a high frequency of promoter hypermethylation of SLIT2 and loss of heterozygosity at 4p15.1–4p15.31 occur at an very early stage in the pathogenesis of CRC [26]. Down-regulation of miR-218 may play a vital role in CRC initiation.

miR-218 functions as a tumor suppressor gene in various cancer targeting many genes to regulate biological processes globally [16-19,21,28]. Overex-pression of miR-218 can inhibit cancer cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis, and promote cancer cell apoptosis [16-19,21,28]. Leite et al. [20] reported that the expression level of miR-218 in high grade prostate cancer was high than those in metastatic prostate cancer. Wu et al. [29] found that low miR-218 expression was associated with worse survival time. In this study, we found that miR-218 expression was closely related to TNM Stage, LNM, differentiation and worse survival time. Furthermore, the expression levels of miR-218 were significantly decreased in patients with TNM stages II~IV compared with those with TNM stage I. These results indicated that decreased miR-218 expression may be associated with CRC progression.

Although the source of the endogenous circulating miRNAs and the precise cellular release mechanisms of miRNAs remain unknown, many studies have revealed that circulating miRNAs are not only derived from circulating tumor cells and blood cells, but also originate from cancer tissues or other tissue cells affected by disease [30]. Aberrant miRNA expression in circulation has been observed in various cancers [6,30-32]. Furthermore, circulating miRNAs remain stable even after exposure to severe physicochemical conditions, such as extreme pH, long-time storage at room temperature [23,31]. Many studies have reported on the use of circulating miRNAs as diagnostic or prognostic biomarker for human cancer, including lung cancer, CRC. In the present study, we found that serum miR-218 levels were dramatically reduced in CRC patients. This was in keeping with previous study which found reduced miR-218 expression in plasma of gastric cancer [22]. Some studies revealed that expression levels of circulating miRNAs changed after anti-cancer treatment [33]. Therefore, we further explore the potential impact of CRC surgery on serum miR-218. The expression level of serum miR-218 was weak but significantly elevated after surgery. Since cancer cells account for only a very tiny fraction of the body mass, circulating miR-218 may be mostly derived from normal cells. Decreased serum miR-218 level in CRC patients may be the result of reduced secretion in normal cells affected by their interaction with cancer cells. We propose that the curative resection lead to removing influence of cancer cells on normal cells, the level of miR-218 in turn elevated. Further studies with larger samples are required to validate these results.

In summary, we provide the evidence that miR-218 was downregulated in tissues and sera of CRC patients, and may act as independent prognostic factors for CRC patients. miR-218 is a candidate target gene for future cancer therapeutics.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Natural Science Fund programs of Nantong University (10Z088).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He J, Chen WQ. 2012 Chinese Cancer Registry Annual Report. Military Medical Science Press; 2012. pp. 28–57. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill DA, Furman WL, Billups CA, Riedley SE, Cain AM, Rao BN, Pratt CB, Spunt SL. Colorectal carcinoma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5808–5814. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordes KR, Srivastava D. MicroRNA regulation of cardiovascular development. Circ Res. 2009;104:724–732. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen J, Stass SA, Jiang F. MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers in human solid tumors. Cancer Lett. 2013;329:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulivi P, Foschi G, Mengozzi M, Scarpi E, Silvestrini R, Amadori D, Zoli W. Peripheral Blood miR-328 Expression as a Potential Biomarker for the Early Diagnosis of NSCLC. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:10332–10342. doi: 10.3390/ijms140510332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Q, Si Q, Xiao S, Xie Q, Lin J, Wang C, Chen L, Chen Q, Wang L. Prognostic significance of serum miR-17-5p in lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:353. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0353-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volinia S, Croce CM. Prognostic microRNA/mRNA signature from the integrated analysis of patients with invasive breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7413–7417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304977110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Q, Chen T, Lin Q, Lin G, Lin J, Chen G, Guo L. Serum miR-19a expression correlates with worse prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:767–771. doi: 10.1002/jso.23312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamez-Pozo A, Anton-Aparicio LM, Bayona C, Borrega P, Gallegos Sancho MI, Garcia-Dominguez R, de Portugal T, Ramos-Vazquez M, Perez-Carrion R, Bolos MV, Madero R, Sanchez-Navarro I, Fresno Vara JA, Espinosa Arranz E. MicroRNA expression profiling of peripheral blood samples predicts resistance to first-line sunitinib in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients. Neoplasia. 2012;14:1144–1152. doi: 10.1593/neo.12734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson JA, Bryan K, Williams R, Popov S, Vujanic G, Coulomb A, Boccon-Gibod L, Graf N, Pritchard-Jones K, O’Sullivan M. miRNA rofiles as a predictor of chemoresponsiveness in Wilms’ tumor blastema. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svoboda M, Sana J, Fabian P, Kocakova I, Gombosova J, Nekvindova J, Radova L, Vyzula R, Slaby O. MicroRNA expression profile associated with response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer patients. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:195. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson MR, Larsen JE, Yang IA, Hayward NK, Clarke BE, Duhig EE, Passmore LH, Bowman RV, Fong KM. MicroRNA-218 is deleted and downregulated in lung squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Kawakami K, Tatarano S, Uchida Y, Kawahara K, Nishiyama K, Seki N, Nakagawa M. Functional role of LASP1 in cell viability and its regulation by microRNAs in bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2012;30:434–443. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song L, Huang Q, Chen K, Liu L, Lin C, Dai T, Yu C, Wu Z, Li J. miR-218 inhibits the invasive ability of glioma cells by direct downregulation of IKK-beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tie J, Pan Y, Zhao L, Wu K, Liu J, Sun S, Guo X, Wang B, Gang Y, Zhang Y, Li Q, Qiao T, Zhao Q, Nie Y, Fan D. MiR-218 inhibits invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer by targeting the Robo1 receptor. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Ping Z, Ning H. MiR-218 Impairs Tumor Growth and Increases Chemo-Sensitivity to Cisplatin in Cervical Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:16053–16064. doi: 10.3390/ijms131216053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He X, Dong Y, Wu CW, Zhao Z, Ng SS, Chan FK, Sung JJ, Yu J. MicroRNA-218 inhibits cell cycle progression and promotes apoptosis in colon cancer by downregulating BMI1 polycomb ring finger oncogene. Mol Med. 2012;18:1491–1498. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leite KR, Sousa-Canavez JM, Reis ST, Tomiyama AH, Camara-Lopes LH, Sanudo A, Antunes AA, Srougi M. Change in expression of miR-let7c, miR-100, and miR-218 from high grade localized prostate cancer to metastasis. Urol Oncol. 2011;29:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uesugi A, Kozaki K, Tsuruta T, Furuta M, Morita K, Imoto I, Omura K, Inazawa J. The tumor suppressive microRNA miR-218 targets the mTOR component Rictor and inhibits AKT phosphorylation in oral cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5765–5778. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li BS, Zhao YL, Guo G, Li W, Zhu ED, Luo X, Mao XH, Zou QM, Yu PW, Zuo QF, Li N, Tang B, Liu KY, Xiao B. Plasma microRNAs, miR-223, miR-21 and miR-218, as novel potential biomarkers for gastric cancer detection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O’Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickinson RE, Dallol A, Bieche I, Krex D, Morton D, Maher ER, Latif F. Epigenetic inactivation of SLIT3 and SLIT1 genes in human cancers. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:2071–2078. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shivapurkar N, Maitra A, Milchgrub S, Gazdar AF. Deletions of chromosome 4 occur early during the pathogenesis of colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:169–177. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.21560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beggs AD, Jones A, Shepherd N, Arnaout A, Finlayson C, Abulafi AM, Morton DG, Matthews GM, Hodgson SV, Tomlinson IP. Loss of expression and promoter methylation of SLIT2 are associated with sessile serrated adenoma formation. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alajez NM, Lenarduzzi M, Ito E, Hui AB, Shi W, Bruce J, Yue S, Huang SH, Xu W, Waldron J, O’Sullivan B, Liu FF. MiR-218 suppresses nasopharyngeal cancer progression through downregulation of survivin and the SLIT2-ROBO1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2381–2391. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto N, Kinoshita T, Nohata N, Itesako T, Yoshino H, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Shozu M, Seki N. Tumor suppressive microRNA-218 inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion by targeting focal adhesion pathways in cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1523–1532. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu DW, Cheng YW, Wang J, Chen CY, Lee H. Paxillin predicts survival and relapse in non-small cell lung cancer by microRNA-218 targeting. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10392–10401. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mo MH, Chen L, Fu Y, Wang W, Fu SW. Cell-free Circulating miRNA Biomarkers in Cancer. J Cancer. 2012;3:432–448. doi: 10.7150/jca.4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang K, Guo J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Guo X, Li Q, Li X, Wang W, Zhang Y, Wang J, Jiang X, Xiang Y, Xu C, Zheng P, Zhang J, Li R, Zhang H, Shang X, Gong T, Ning G, Wang J, Zen K, Zhang J, Zhang CY. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008;18:997–1006. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chin LJ, Slack FJ. A truth serum for cancer--microRNAs have major potential as cancer biomarkers. Cell Res. 2008;18:983–984. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun Y, Wang M, Lin G, Sun S, Li X, Qi J, Li J. Serum microRNA-155 as a potential biomarker to track disease in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]